Abstract

Background and objectives

Chronic pain in predialysis CKD is not fully understood. This study examined chronic pain in CKD and its relationship with analgesic usage.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Data include baseline visits from 308 patients with CKD enrolled between 2011 and 2013 in the Safe Kidney Care cohort study in Baltimore, Maryland. The Wong–Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale measured chronic pain severity. Analgesic prescriptions and over-the-counter purchases were recorded up to 30 days before visits, and were classified as a drug-related problem (DRP) based on an analgesic’s nephrotoxicity and dose appropriateness at participants’ eGFR. Participants were sorted by pain frequency and severity and categorized into ordinal groups. Analgesic use and the rate of analgesics with a DRP were reported across pain groups. Multivariate regression determined the factors associated with chronic pain and assessed the relationship between chronic pain and analgesic usage.

Results

There were 187 (60.7%) participants who reported chronic pain. Factors associated with pain severity included arthritis, taking ≥12 medications, and lower physical function. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs was reported by seven participants (5.8%) with no chronic pain. Mild and severe chronic pain were associated with analgesics with a DRP, with odds ratios of 3.04 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.12 to 8.29) and 5.46 (95% CI, 1.85 to 16.10), respectively. The adjusted rate of analgesics with a DRP per participant increased from the group with none to severe chronic pain, with rates of 0.07 (95% CI, 0.04 to 0.13), 0.12 (95% CI, 0.07 to 0.20) and 0.16 (95% CI, 0.09 to 0.27), respectively.

Conclusions

Chronic pain is common in CKD with a significant relationship between the severity of pain and both proper and improper analgesic usage. Screening for chronic pain may help in understanding the role of DRPs in the delivery of safe CKD care.

Keywords: patient safety, CKD, pain, analgesics

Introduction

Pain is reported in up to one third of United States adults and is often an underappreciated adjunct of chronic disease (1–3). Pain in patients with multiple comorbidities contributes to impaired well being, poor physical function, depression, quality of care, and health care overutilization (4–8). Chronic pain is reported to be prevalent in ESRD (9–13), but is less commonly studied in predialysis CKD (12,13). The causes of chronic pain across the spectrum of kidney disease are not well understood.

Chronic pain often leads to analgesic use (14), but some of these medications’ prescription and dosing require special consideration with impaired renal function (11–13). Prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) purchase of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are more common in CKD than desirable because they are considered nephrotoxic (15–18). There is also improper prescription or misdirected use of other nonopioid and opioid analgesics because of limits to dosing in CKD, which may not be recognized by providers (19–21).

Given the potential for improper prescription or OTC analgesic use with reduced renal function (referred to as drug-related problems [DRPs]), it is important to understand how pain influences medication safety in patients with CKD. In this study, we estimate the prevalence, frequency, and severity of chronic pain in predialysis CKD, and explore its relationship with proper analgesic dosing and DRPs with impaired renal function.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

This descriptive study used baseline data from the ongoing longitudinal Safe Kidney Care (SKC) Study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01407367) examining CKD-specific patient safety (22,23). SKC participants (n=308) were recruited from University of Maryland Medical System and Baltimore Veterans Administration Medical Center between April 15, 2011, and November 30, 2013. For study inclusion, participants needed two eGFR values of <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, using the abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation (24) (the clinical measure of renal function at the time of study), and spaced at least 90 days apart, but within the prior 18 months. Patients who were aged <21 years or expected to need dialysis or die within 12 months were excluded.

The study was approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board and the Baltimore Veterans Affairs Research and Development Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before study enrollment.

Measurements

At the SKC visit, demographics, medical history, self-reported safety events, and physical measurements were obtained and serum creatinine, potassium, glucose, and venous hemoglobin were collected as previously described (25). The Short Physical Performance Battery test was administered to measure physical function (26).

Assessment of Pain Severity

A pain questionnaire determined the presence, frequency, and intensity of chronic pain at the baseline visit and over the prior 12 months. Report of chronic pain relied on self-report and was based on the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke definition of chronic pain, which states the pain should be persistent for weeks, months, or even years (27). Participants reporting chronic pain were asked whether they experienced the pain less than once a month, 1–3 times per month, 1–2 times a week, 3–4 times a week, or daily. Participants rated the pain at its worst at the time of the visit, at its best, and at what level it was acceptable using the Wong–Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale (WBFPRS), which consists of six faces ranging from 0 (“no hurt”) to 10 (“hurts worst”) (28). The WBFPRS was chosen because it is typically utilized per the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations (JCAHO) mandate to assess and manage patients’ pain in regulated health care settings (29). Finally, the pain questionnaire asked if participants took analgesics in the prior 30 days.

Classification of Analgesics and DRPs

Analgesic prescriptions or OTC purchases were recorded and categorized as NSAIDs, opioid analgesics, or nonopioid analgesics, and were given one of three designations (flags). These designations were (1) appropriate dosing, or one of two DRPs as follows: (2) dosing of an opioid or nonopioid improperly at a participant’s eGFR at the time of dosing, or (3) a NSAID, which were considered a DRP, regardless of eGFR (16). The classification of a DRP relies on nomenclature described by Strand et al. 1990 (30,31) and includes any analgesic with (1) a dose exceeding the upper threshold of dosing for a given eGFR or (2) a nonspecific recommendation for dose reduction, avoidance, or general caution with use in CKD. Many analgesics have published dosing guidance varying by eGFR, which accounts for participants having different flags for specific analgesics. DRP classification was determined with the second screening eGFR because it was considered reflective of the renal function known by the provider at the time of the prescription. Combination drugs were separated into individual components and flagged independently. Aspirin, which can be used for prevention of cardiovascular events, was considered to be used for pain if it was in combination analgesic (e.g., Excedrin), was taken at a daily dosage >325 mg, or taken more than once a day.

Renal dosing information for analgesics was obtained primarily from Micromedex (32), but supplemented with data from Drug Facts and Comparisons (33), American Hospital Formulary Service (34), Lexicomp online (35), the Directory of Drug Dosage in Kidney Disease (36), and the Directory of Drug Dosage in Renal Failure: Dosing Guidelines for Adults (37,38).

Statistical Analyses

To determine factors associated with chronic pain, and the association of chronic pain with the odds of proper analgesic use or a DRP, we created composite pain groups composed of the different aspects of pain reported. We created three ordinal groups using a sorting scheme ranking participants first based on frequency of chronic pain, followed by pain severity at its worst, and then pain at the time of the SKC visit. The three ordinal groups were composed of those who did not report chronic pain in the “no chronic pain” group, and then those with a mid-rank and lowest overall rank in the “mild chronic pain” and “severe chronic pain” groups, respectively. This strategy allowed us to differentiate those with mild and severe pain based on the sum of the WBFPRS response for pain at its worst and at the SKC visit.

For descriptive analyses, the chi-squared test and t test were used to compare the categorical characteristics and continuous variables, respectively, across the three composite pain groups. Participants were also stratified solely on frequency of chronic pain for the purpose of describing other aspects of pain assessment along with their analgesic use. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was used to determine the demographic and comorbidity correlates of chronic pain severity, and the association of the severity of chronic pain with both properly dosed analgesics and analgesics with a DRP. In the multinomial logistic models, we assumed the predictors were linearly and independently related to the odds ratio (OR) of both mild and severe chronic pain relative to no pain, and the odds of a properly dosed analgesics, or analgesic with a DRP relative to no use. Covariates adjusted for in the analysis were the factors included in Table 1. The rate of analgesics with a DRP per all participants in each composite pain category was computed using Poisson regression and adjusted for covariates at their mean value. Statistical tests used two-sided hypothesis testing and a P value <0.05 indicated statistical significance. The analyses were done using IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 software with verification by SAS (version 9.3).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants by pain severity and adjusted odds ratios of each factor with associated pain severity

| Demographic Characteristics | Pain Severity Groups | Multivariate Model Predicting Pain Severityd | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Chronic Pain | Mild Chronic Pain | Severe Chronic Pain | Mild Chronic Pain | Severe Chronic Pain | |

| Participants, n | 121 (39.3) | 97 (31.5) | 90 (29.2) | 97 | 90 |

| Age, yr | 65.9±12.4 | 66.5±11.1 | 64.7±8.8 | ||

| ≥65 | 75 (62.0) | 55 (56.7) | 46 (51.1) | 0.52 (0.26 to 1.01) | 0.32 (0.15 to 0.66) |

| <65 | 46 (38.0) | 42 (43.3) | 44 (48.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 96 (79.3) | 67 (69.1) | 61 (67.8) | 0.81 (0.40 to 1.68) | 0.86 (0.40 to 1.87) |

| Women | 25 (20.7) | 30 (30.9) | 29 (32.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | |||||

| Yes | 87 (71.9) | 60 (61.9) | 62 (68.9) | 0.53 (0.27 to 1.03) | 0.73 (0.35 to 1.54) |

| No | 34 (28.1) | 37 (38.1) | 28 (31.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| BMIa | 30.4±6.8 | 33.6±8.0 | 33.9±6.2 | ||

| ≥30 | 63 (52.5) | 61 (63.5) | 61 (68.5) | 1.43 (0.74 to 2.78) | 1.68 (0.80 to 3.51) |

| <30 | 57 (47.5) | 35 (36.5) | 28 (31.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| eGFR | 40.6±10.9 | 40.1±11.3 | 41.3±10.4 | ||

| ≤45 | 74 (61.2) | 59 (60.8) | 50 (55.6) | 0.99 (0.53 to 1.84) | 0.97 (0.49 to 1.92) |

| >45 | 47 (38.8) | 38 (39.2) | 40 (44.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| MAPb | 88.6±13.7 | 89.3±13.4 | 87.2±13.0 | ||

| ≥96.7 | 87 (72.5) | 71 (74.0) | 72 (80.9) | 1.13 (0.55 to 2.32) | 0.85 (0.37 to 1.91) |

| <96.7 | 33 (27.5) | 25 (26.0) | 17 (19.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Gout | |||||

| Yes | 41 (33.9) | 38 (39.2) | 36 (40.0) | 1.00 (0.53 to 1.91) | 0.85 (0.42 to 1.72) |

| No | 80 (66.1) | 59 (60.8) | 54 (60.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Arthritis | |||||

| Yes | 28 (23.1) | 60 (61.9) | 65 (73.0) | 4.63 (2.40 to 8.94) | 8.22 (3.95 to 17.13) |

| No | 93 (76.9) | 37 (38.1) | 24 (27.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Cancer | |||||

| Yes | 30 (25.0) | 17 (17.5) | 22 (24.4) | 0.63 (0.29 to 1.38) | 1.02 (0.46 to 2.29) |

| No | 90 (75.0) | 80 (82.5) | 68 (75.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Diabetes | |||||

| Yes | 69 (57.0) | 64 (66.0) | 63 (70.0) | 0.89 (0.44 to 1.79) | 0.73 (0.34 to 1.58) |

| No | 52 (43.0) | 33 (34.0) | 27 (30.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Smoking past 3 mo | |||||

| Yes | 27 (22.3) | 16 (16.5) | 14 (15.6) | 0.84 (0.38 to 1.90) | 0.79 (0.32 to 1.95) |

| No | 94 (77.7) | 81 (83.5) | 76 (84.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| SPPB score | 8.9±2.5 | 8.1±2.5 | 7.9±2.8 | ||

| <9 | 34 (28.1) | 48 (49.5) | 48 (53.3) | 1.96 (1.03 to 3.74) | 2.01 (1.00 to 4.08)e |

| ≥9 | 87 (71.9) | 49 (50.5) | 42 (46.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medicationsc | 11 (7–13) | 12 (10–18) | 15 (12–18) | ||

| ≥12 | 46 (38.0) | 57 (58.8) | 69 (76.7) | 2.14 (1.11 to 4.11) | 5.02 (2.38 to 10.60) |

| <12 | 75 (62.0) | 40 (41.2) | 21 (23.3) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Data are presented as the mean±SD, median (interquartile range), or odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) unless otherwise indicated. BMI, body mass index; MAP, mean arterial pressure; SPPB: Short Performance Physical Battery.

Missing three participants due to inability to take height measurements.

MAP from baseline visit was used to factor in systolic and diastolic BP (one missing value).

Any medication with multiple components are broken down into their components and reported separately.

Reference group is no chronic pain. Participants with missing values for covariates were excluded from multivariate analyses.

P=0.05.

Results

SKC participants classified into composite pain groups and their characteristics are shown in Table 1. More than half of them had some chronic pain; 97 (31.5%) and 90 (29.2%) were categorized with mild and severe chronic pain, respectively.

Participants with chronic pain had a tendency to be younger, female, not African American, and more likely to report inflammatory arthritis or degenerative arthritis. Participants with chronic pain also reported taking more medications than those without chronic pain and a lower physical function based on their Short Physical Performance Battery score.

In the multivariate analysis, participants who were aged ≥65 years had lower odds of reporting severe pain (OR, 0.32; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.15 to 0.66) than younger participants. Participants with lower physical function, had a higher odds of reporting mild (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.00 to 4.08) and severe pain (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.02 to 3.74). The presence of arthritis was associated with mild (OR, 4.63; 95% CI, 2.40 to 8.94) and severe pain (OR, 8.22; 95% CI, 3.95 to 17.13, respectively), as was taking ≥12 medications (OR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.11 to 4.11; and OR, 5.02; 95% CI, 2.38 to 10.60, respectively). Of note, there was no significant association between body mass index, level of renal function, and other comorbidities with chronic pain on multivariate analysis.

Chronic Pain and Analgesic Use

Table 2 displays the distribution of participants based on the frequency of their chronic pain, and reported aspects of pain severity. The reporting of any analgesic prescription or OTC purchase within the last month is shown for each strata of chronic pain frequency. Among the 187 (60.7%) SKC participants reporting chronic pain, a majority had pain at least 3–4 times a week. The proportion of study participants reporting 0 on the WBFPRS for each dimension of pain severity tended to decline with increasing pain frequency, except for the report of worst chronic pain where the distribution was relatively constant across frequency strata. The report of pain at the study visit (“now”) had the greatest tendency to increase with frequency. Sorting participants in order of pain frequency (Table 2), pain at its worst and at the SKC visit, separates participants into groups of no, mild, and severe pain with significantly different mean WBFPRS sum scores (sum pain score for mild and severe chronic pain: 8.3±0.3 and 14.1±0.2, respectively). Participants in the severe pain group all reported having pain >3–4 times a week, with worst chronic pain scored at ≥8 and 42 (46.6%) members of this group reported a pain score of ≥6 at the study visit. Fewer participants assigned to the mild pain group reported pain in the most frequent stratum, their most severe pain with a score of ≥8, or pain of ≥6 at the study visit (50 [51.5%], 53 [54.6%], and 3 [3.1%], respectively). Of note, almost a quarter of study participants with no chronic pain still reported analgesic prescriptions, but the proportion of participants taking an analgesic in the prior 30 days increased from those with no chronic pain to the most frequent chronic pain.

Table 2.

Distribution of participants (%) by chronic pain frequency, severity scores, and analgesic use over prior 30 days

| How Often Do You Experience Chronic Pain? | n | Analgesic Use in the Last Month, n (%) | Pain Score | Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Score, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | 0 | 1–4 | 5–8 | 9 and 10 | |||

| No chronic pain | 121 | 35 (28.9) | 86 (71.1) | Worst | ||||

| Now | * | * | * | * | ||||

| Acceptable | ||||||||

| Best | ||||||||

| Less than once/mo | 10 | 4 (40.0) | 6 (60.00) | Worst | 3 (30.0) | 3 (30.0) | 4 (40.0) | |

| Now | 7 (70.0) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (10.0) | |||||

| Acceptable | 1 (10.0) | 8 (80.0) | 1 (10.0) | |||||

| Best | 8 (80.0) | 2 (20.0) | ||||||

| 1–3 times/mo or 1–2 times/wk | 37 | 23 (62.2) | 14 (37.8) | Worst | 7 (18.9) | 19 (51.3) | 11(29.7) | |

| Now | 25 (67.6) | 10 (27.0) | 2 (5.4) | |||||

| Acceptable | 2 (5.4) | 30 (81.0) | 5 (13.5) | |||||

| Best | 27 (73.0) | 9 (24.3) | 1 (2.7) | |||||

| 3–4 times/wk or almost everyday | 140 | 101 (72.1) | 39 (27.9) | Worst | 6 (4.3) | 67 (47.8) | 67 (47.8) | |

| Now | 23 (16.4) | 75 (53.5) | 42 (30) | |||||

| Acceptable | 11 (7.9) | 100 (71.5) | 26 (18.6) | 3 (2.1) | ||||

| Best | 45 (32.1) | 87(62.1) | 7 (5.0) | 1 (0.7) | ||||

Chronic Pain and DRPs

Table 3 exhibits study participants distributed by their frequency of chronic pain, and within frequency strata, the count of individuals based on their reported medications by analgesic class. Each table cell shows the proportion of participants within that cell with at least one analgesic that is dosed with a DRP for the participant’s eGFR. The frequency of reporting nonopioid and opioid analgesic was lowest among those with no chronic pain, and concordantly there is the lowest frequency of DRPs for these analgesic classes within each cell. The preponderance of nonopioid and opioid analgesics increased with the frequency of chronic pain, and in the most frequent chronic pain group, there were numerous participants on multiple opioid and nonopioid analgesics. The proportion of individuals within cells with a DRP also increased with frequency of reported chronic pain. A higher proportion of participants with no chronic pain reported NSAID use but among those with chronic pain, NSAID usage increased with pain severity.

Table 3.

Distribution of analgesic use and potential DRP flags for participants classified into pain frequency groups

| How Often Do You Experience Chronic Pain? | n | Analgesic | Counts, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| No chronic pain | 121 | Nonopioid | 93 (76.9) | 27 (22.3) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Opioid | 115 (95.0) | 6 (5.0) | ||||

| NSAIDsa | 114 (94.2) | 7 (5.8) | ||||

| Less than once/mo | 10 | Nonopioid | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) | ||

| Opioid | 9 (90.0) | 1 (10.0) | ||||

| NSAIDsa | 10 (100.0) | |||||

| 1–3 times/mo or 1–2 times/wk | 37 | Nonopioid | 21 (56.8) | 14 (37.8) | 2 (5.4) | |

| Opioid | 23 (62.2) | 14 (37.8) | ||||

| NSAIDsa | 33 (89.2) | 4 (10.8) | ||||

| 3–4 times/wk or almost everyday | 140 | Nonopioid | 74 (52.9) | 59 (42.1) | 7 (5.0) | |

| Opioid | 78 (55.7) | 50 (35.7) | 10 (7.1) | 2 (1.4) | ||

| NSAIDsa | 135 (96.4) | 5 (3.6) | ||||

| Key |

|---|

| % with DRP flag |

| 100% |

| 51-75% |

| 26-50% |

| 1-25% |

| 0% |

DRP, drug-related problem; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Any NSAID use is flagged as a DRP.

Table 4 shows all analgesics, analgesics with DRPs, and NSAIDs as a distinct group reported in the study cohort. Drugs are listed from most frequently taken to least frequently taken in the study. Acetaminophen is the most commonly used analgesic, with three participants reporting a dose greater than the recommended maximum total daily dosage (4000 mg), which is not dependent on GFR. Tramadol is the most commonly used analgesic with a DRP, and ibuprofen is the most commonly used NSAID. Since DRP flags are conferred based on analgesic dosage and the eGFR of each participant, certain medications can have entries with or without a DRP.

Table 4.

Analgesics by frequency of participants with reported prescription or over-the-counter purchase

| All Analgesics Reported | Analgesics Other Than NSAIDs with Reported Dose with DRP | NSAIDs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Name | n (%) | Drug Name | n (%) | Drug Name | n (%) |

| Acetaminophen | 104 (33.8) | Tramadol | 13 (4.2) | Ibuprofen | 6 (1.9) |

| Tramadol | 47 (15.3) | Oxycodone | 4 (1.3) | Naproxen | 5 (1.6) |

| Oxycodone | 25 (8.1) | Hydrocodone and acetaminophen | 4 (1.3) | Indomethacin | 3 (0.9) |

| Codeine | 10 (3.2) | Acetaminophenb | 3 (0.9) | Diclofenac | 1 (0.3) |

| Hydrocodone and acetaminophen | 8 (2.6) | Morphine | 2 (0.6) | Etodolac | 1 (0.3) |

| Aspirina | 7 (2.3) | Aspirina | 2 (0.6) | ||

| Ibuprofen | 6 (1.9) | Butalbital, acetaminophen, and caffeine | 2 (0.6) | ||

| Naproxen | 5 (1.6) | Codeine | 2 (0.6) | ||

| Morphine | 3 (0.9) | Sulfasalazine | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Indomethacin | 3 (0.9) | ||||

| Butalbital, acetaminophen, and caffeine | 2 (0.6) | ||||

| Diclofenac | 1 (0.3) | ||||

| Etodolac | 1 (0.3) | ||||

| Methadone | 1 (0.3) | ||||

| Salsalate | 1 (0.3) | ||||

| Sulfasalazine | 1 (0.3) | ||||

Aspirin included as analgesic at a dosage >325 or taken more than once a day.

Acetaminophen DRP is for the maximum dosage of >4000 mg daily that is not GFR dependent.

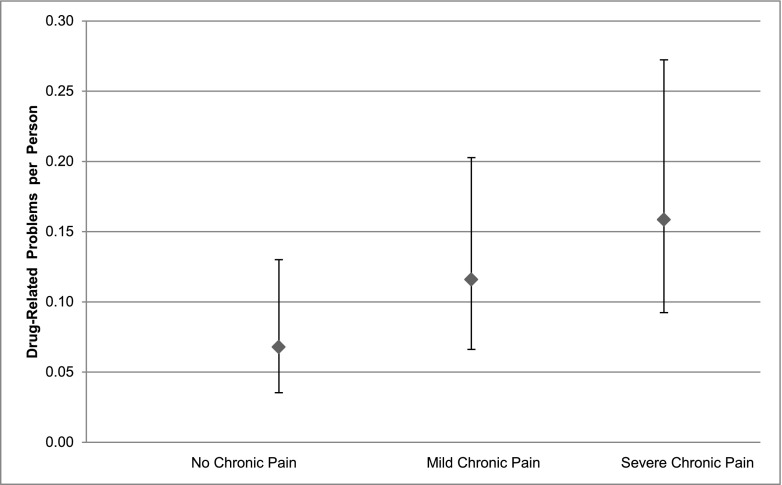

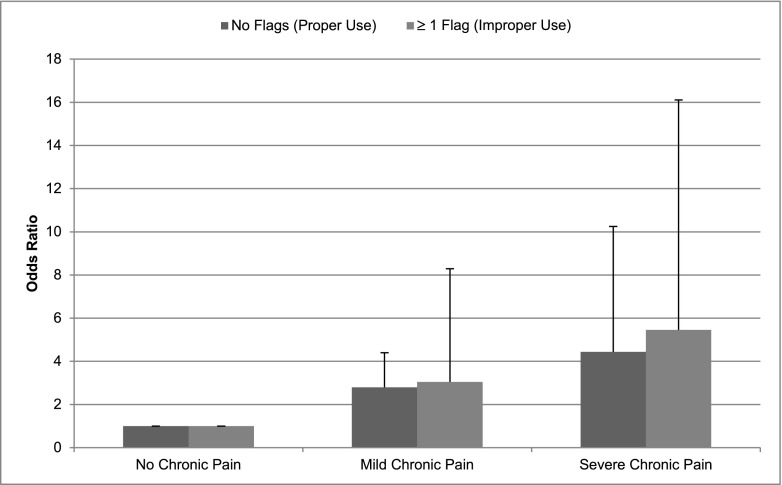

Figure 1 shows the adjusted OR of analgesic use, dosed properly or with a DRP, versus no analgesics, comparing participants with mild chronic pain or severe chronic pain to no pain as reference. Figure 2 displays the rate of analgesics with DRPs per participant by chronic pain status. The odds of being prescribed an analgesic either properly dosed or with a DRP, relative to no analgesic use, increased across the groups from those with no pain to those with mild (proper dosing OR, 2.79; 95% CI, 1.29 to 6.05; and DRP OR, 3.04; 95% CI, 1.12 to 8.29; P=0.01 and P=0.03, respectively), and greater in the more severe chronic pain group (proper dosing OR, 4.44; 95% CI, 1.93 to 10.24; and DRP OR, 5.46; 95% CI, 1.85 to 16.10; P<0.001 and P=0.002, respectively). The adjusted rate of analgesics with a DRP per person increased from those with no pain to mild and severe chronic pain although only significantly for the latter, with adjusted rates of DRP (per person) of 0.07 (95% CI, 0.04 to 0.13), 0.12 (95% CI, 0.07 to 0.20), and 0.16 (95% CI, 0.09 to 0.27) for none, mild, and severe chronic pain, respectively (mild pain versus no pain group, P=0.17; severe pain versus no pain group, P=0.04).

Figure 1.

The y axis exhibits the adjusted rate of DRPs per participant (95% confidence intervals) in each pain group. P=0.17 for the mild pain versus no pain group. P=0.04 for the severe pain versus no pain group. Sample sizes for groups are 121, 97, and 90, respectively. DRP, drug-related problem.

Figure 2.

The y axis exhibits the adjusted odds ratios of analgesic use, dosed properly or with a DRP (improper use) relative to no analgesics comparing participants with mild chronic pain to no pain (reference) (P=0.01 and P=0.03, for proper dosing or DRP, respectively) or severe chronic pain to no pain (P=0.001 and P=0.02, for proper dosing or DRP, respectively).

Discussion

This study demonstrates chronic pain is reported in many patients with CKD, and often with some regularity and severity. Factors associated with chronic pain in CKD include younger age and arthritis, and CKD patients with chronic pain have poly-pharmacy and reduced physical function. The relationship between chronic pain and analgesics can be characterized by a pattern of greater analgesic use with more frequent pain. However, NSAID use was noted even among participants without chronic pain. NSAIDs are the least commonly prescribed of the three groups of analgesics; nonetheless, their reporting by study participants is notable since these analgesics are generally contraindicated in CKD. The report of opioid and nonopioid analgesics use and the DRPs within these drug classes increased with chronic pain frequency.

In 2001, the JCAHO required the assessment and documentation of pain management as criteria for hospitals and associated clinics to maintain certification. Pain assessment has become the fifth vital sign and is typically evaluated with semiquantitative instruments such as the WBFPRS (29). At least one study demonstrated an increase in adverse events related to opioid use when comparing patients hospitalized before and after the JCAHO mandate (39); however; further studies are needed to determine the benefits and harm from such mandated pain assessments. Given the pertinence of medication safety in CKD care, it is important to better understand the relationship between chronic pain and analgesic use in CKD and to improve pain management because it is often inadequate (7,40). Limited information is available on the extent to which nonpharmacologic strategies are utilized to treat chronic pain in CKD (41). Identifying alternative means to control chronic pain in CKD might mitigate the rate of improper analgesic use, which is noted in this study. Future efforts will need to examine the effect of mandated pain assessment on analgesic use among CKD patients in both the hospital and clinics.

The study findings are consistent with reports showing chronic pain is common in predialysis CKD affecting a majority of patients (12). NSAID prescription and use are prevalent in CKD, despite recommendations against their use (15,18,42). Population-based surveys also show a significant need for opioid analgesics among adults with chronic pain, even if mild (40). Others report significant analgesic use among survey respondents who do not experience pain often (43), which could explained by the effectiveness of analgesics in preventing pain and their continued use to maintain a pain-free state (43).

This descriptive study has limitations to consider when interpreting the results. The information collected from the questionnaires relating to pain and medical history was self-reported with the potential for recall bias influencing the relationship between chronic pain and analgesic use. Pain-free study participants taking analgesics at the study visit may have failed to report the pain that was resolved with analgesic use at the time of assessment. Study-reported analgesic prescriptions and OTC purchases are imperfect proxies for usage. However, prescription and purchase reflect intent of providers and patients and offer insights into practice and behavioral patterns that impact medication safety.

Our sample size is smaller than other epidemiologic studies, which limits its capability to explore nonlinear relationships between chronic pain and reported analgesic use; however, the detail of information collected offsets the limitations in power. The limits of sample size may also explain lack of association between analgesic use and eGFR, but longitudinal follow-up is more likely to elucidate a relationship between analgesic use, including with NSAIDs, and harm to renal function. The study participants were recruited from academic medical centers, which may limit the generalizability of the findings; however, the prevalence of analgesic use leading to DRPs is likely to be higher in settings without the availability of subspecialty comanagement. Especially since the link between more severe chronic pain and difficulty in its control is likely to influence the frequency of DRPs in dosing. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize this relationship in order to better understand medication safety in CKD. Finally, the analysis does not examine the consequences or harms related to the DRPs identified as this will be the subject of future analyses of the SKC cohort over its longitudinal follow-up. However, excessive dosing of analgesics or their use in clinical conditions where they are ill advised is important to recognize.

In conclusion, chronic pain is common in predialysis CKD and the effectiveness of its management should be explored in individual patients. The severity of chronic pain is linked to both proper and potentially hazardous analgesic use. Given the prevalence of chronic pain and analgesic use in CKD patients, greater attention and should be given to devising optimal pain management strategies as a means to improve medication safety and effectively address the health needs of this population.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Participation in this project was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant DK084017 to J.C.F., M.Z., J.S.G., J.C., and C.W.), the University of Maryland School of Medicine Summer Program in Obesity, Diabetes, and Nutrition Research Training (NIH grant T35-DK095737 to J.W.), the University of Maryland Clinical Translational Science Institute, and the University of Maryland General Clinical Research Center.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Pain, Analgesics, and Safety in Patients with CKD,” on pages 350–352.

References

- 1.Johannes CB, Le TK, Zhou X, Johnston JA, Dworkin RH: The prevalence of chronic pain in United States adults: Results of an Internet-based survey. J Pain 11: 1230–1239, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B: Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 380: 37–43, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Hecke O, Torrance N, Smith BH: Chronic pain epidemiology and its clinical relevance. Br J Anaesth 111: 13–18, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butchart A, Kerr EA, Heisler M, Piette JD, Krein SL: Experience and management of chronic pain among patients with other complex chronic conditions. Clin J Pain 25: 293–298, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K: Depression and pain comorbidity: A literature review. Arch Intern Med 163: 2433–2445, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Hecke O, Torrance N, Smith BH: Chronic pain epidemiology–where do lifestyle factors fit in [published ahead of print June 19, 2013]? Br J Pain 10.1177/2049463713493264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D: Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 10: 287–333, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, Cousins MJ: Chronic pain and frequent use of health care. Pain 111: 51–58, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mercadante S, Ferrantelli A, Tortorici C, Lo Cascio A, Lo Cicero M, Cutaia I, Parrino I, Casuccio A: Incidence of chronic pain in patients with end-stage renal disease on dialysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 30: 302–304, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davison SN: The prevalence and management of chronic pain in end-stage renal disease. J Palliat Med 10: 1277–1287, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurella M, Bennett WM, Chertow GM: Analgesia in patients with ESRD: A review of available evidence. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 217–228, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pham PT, Toscano E, Pham PT, Pham PT, Pham SV,Pham PT: Pain management in patients with chronic kidney disease. NDT Plus 2: 111–118, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams A, Manias E: A structured literature review of pain assessment and management of patients with chronic kidney disease. J Clin Nurs 17: 69–81, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark JD: Chronic pain prevalence and analgesic prescribing in a general medical population. J Pain Symptom Manage 23: 131–137, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plantinga L, Grubbs V, Sarkar U, Hsu CY, Hedgeman E, Robinson B, Saran R, Geiss L, Burrows NR, Eberhardt M, Powe N, CDC CKD Surveillance Team : Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use among persons with chronic kidney disease in the United States. Ann Fam Med 9: 423–430, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gooch K, Culleton BF, Manns BJ, Zhang J, Alfonso H, Tonelli M, Frank C, Klarenbach S, Hemmelgarn BR: NSAID use and progression of chronic kidney disease. Am J Med 120: e1–e7, e7, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whelton A: Nephrotoxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Physiologic foundations and clinical implications. Am J Med 106[5B]: 13S–24S, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel K, Diamantidis C, Zhan M, Hsu VD, Walker LD, Gardner J, Weir MR, Fink JC: Influence of creatinine versus glomerular filtration rate on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug prescriptions in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol 36: 19–26, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paramanandam G, Prommer E, Schwenke DC: Adverse effects in hospice patients with chronic kidney disease receiving hydromorphone. J Palliat Med 14: 1029–1033, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nayak-Rao S: Achieving effective pain relief in patients with chronic kidney disease: A review of analgesics in renal failure. J Nephrol 24: 35–40, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Böger RH: Renal impairment: a challenge for opioid treatment? The role of buprenorphine. Palliat Med 20[Suppl 1]: s17–s23, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diamantidis CJ, Fink W, Yang S, Zuckerman MR, Ginsberg J, Hu P, Xiao Y, Fink JC: Directed use of the internet for health information by patients with chronic kidney disease: Prospective cohort study. J Med Internet Res 15: e251, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diamantidis CJ, Zuckerman M, Fink W, Aggarwal S, Prakash D, Fink JC: Usability testing and acceptance of an electronic medication inquiry system for CKD patients. Am J Kidney Dis 61: 644–646, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens LA, Zhang YL, Hendriksen S, Kusek JW, Van Lente F, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration : Using standardized serum creatinine values in the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 145: 247–254, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ginsberg JS, Zhan M, Diamantidis CJ, Woods C, Chen J, Fink JC: Patient-reported and actionable safety events in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1564–1573, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Scherr PA, Wallace RB: A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 49: M85–M94, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Institute of Neurological Disorders: Chronic pain information. Available at http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/chronic_pain/chronic_pain.htm. Accessed June 14, 2014

- 28.Wong DL, Baker CM: Pain in children: Comparison of assessment scales. Pediatr Nurs 14: 9–17, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phillips DM, Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations : JCAHO pain management standards are unveiled. JAMA 284: 428–429, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strand LM, Cipolle RJ, Morley PC: Documenting the clinical pharmacist’s activities: Back to basics. Drug Intell Clin Pharm 22: 63–67, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cardone KE, Bacchus S, Assimon MM, Pai AB, Manley HJ: Medication-related problems in CKD. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 17: 404–412, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Truven Health Analytics Inc: Micromedex healthcare series. Available at http://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed April 1, 2014

- 33.Wolters Kluwer Health Inc: Drug facts and comparisons. Available at http://www.factsandcomparisons.com/facts-comparisonsonline/. Accessed April 1, 2014

- 34.American Society of Health System Pharmacists publication: AHFS updates on-line. Available at http://www.ahfsdruginformation.com/product-ahfs-di.aspx. Accessed April 1, 2014

- 35.Lexicomp: Lexicomp online. Available at http://online.lexi.com/lco/action/home/switch. Accessed April 1, 2014

- 36.Seyffart G: Seyffart's Directory of Drug Dosage in Kidney Disease, Orlando, FL, Dustri-Verlag, Dr. Karl Feistle GmbH & Co KG, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bennett WM, Aronoff GR, Morrison G, Golper TA, Pulliam J, Wolfson M, Singer I: Drug prescribing in renal failure: Dosing guidelines for adults. Am J Kidney Dis 3: 155–193, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aronoff GR: Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure: Dosing Guidelines for Adults, 5th Ed., East Peoria, IL, Versa Press, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vila H, Jr, Smith RA, Augustyniak MJ, Nagi PA, Soto RG, Ross TW, Cantor AB, Strickland JM, Miguel RV: The efficacy and safety of pain management before and after implementation of hospital-wide pain management standards: Is patient safety compromised by treatment based solely on numerical pain ratings? Anesth Analg 101: 474–480, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toblin RL, Mack KA, Perveen G, Paulozzi LJ: A population-based survey of chronic pain and its treatment with prescription drugs. Pain 152: 1249–1255, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davison SN, Koncicki H, Brennan F: Pain in chronic kidney disease: A scoping review. Semin Dial 27: 188–204, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei L, MacDonald TM, Jennings C, Sheng X, Flynn RW, Murphy MJ: Estimated GFR reporting is associated with decreased nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug prescribing and increased renal function. Kidney Int 84: 174–178, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turunen JH, Mäntyselkä PT, Kumpusalo EA, Ahonen RS: Frequent analgesic use at population level: Prevalence and patterns of use. Pain 115: 374–381, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]