Abstract

The facial growth of Class III malocclusion worsens with age, in this case, the early orthopedic treatment, providing facial balance, modifying the maxillofacial growth and development. A 7.6-year old boy presented with Class III malocclusion associated with anterior crossbite; the mandible was shifted to the right and the maxilla had a transversal deficiency. Rapid maxillary expansion followed by facemask therapy was performed, to correct the anteroposterior relationship and improve the facial profile. The patient was followed for a 15-year period, after completion of the treatment, and stability was observed. Growing patients should be monitored following their treatment, so as to prevent malocclusion relapse.

Keywords: Interceptive orthodontics, Corrective orthodontics, Angle Class III malocclusion

INTRODUCTION

The treatment of Class III malocclusion poses one of the biggest problems for the orthodontist, due to mandibular growth 27 . Studies on facial growth demonstrate that the maxillary growth ends before that of the mandible 13 , 16 , 18 . Thus, Class III discrepancy worsens with age 6 , 24 .

The early orthopedic treatment of Class III malocclusions, at the end of primary dentition or the beginning of mixed dentition, prior to growth spurt, allows the accomplishment of successful results, providing facial balance, modifying the maxillofacial growth and development, and, in many instances, preventing a future surgical treatment by increasing the stability 1 , 2 , 14 .

Late permanent dentition therapy may be difficult, and the approach to compensate malocclusion usually involves tipping of the upper incisors anteriorly and tipping lower incisors lingually. However, that does not solve the skeletal and facial profile problems 5 , 26 . An orthodontic and surgical treatment is indicated to treat a facial aesthetic problem.

The early Class III treatment has many advantages: it facilitates the eruption of canines and premolars in a normal relation, eliminates the traumatic occlusion of incisors, which might lead to gingival recession, provides an adequate maxillary growth, and improves the self esteem of the child.

Most Class III malocclusions present a maxillary retraction. Thus, some researchers claim that these cases can be treated with a maxillary protraction mask, following rapid maxillary expansion 7 , 20 , 27 , aiming at providing an anterior maxillary growth.

The facemask therapy produces one or more of the following effects: correction of the discrepancy between centric relation and centric occlusion, skeletal maxillary protraction from 1 to 2 mm, anterior movement of the upper teeth and tipping of the lower teeth to the lingual side. The effects have a greater impact on younger patients; however, they must be monitored during their facial growth, due to posttreatment relapse 29 .

This case report describes the early orthopedic treatment and stability of Class III malocclusion, achieved by rapid maxillary expansion and facemask therapy, 15 years posttreatment.

CASE REPORT

Diagnosis and etiology

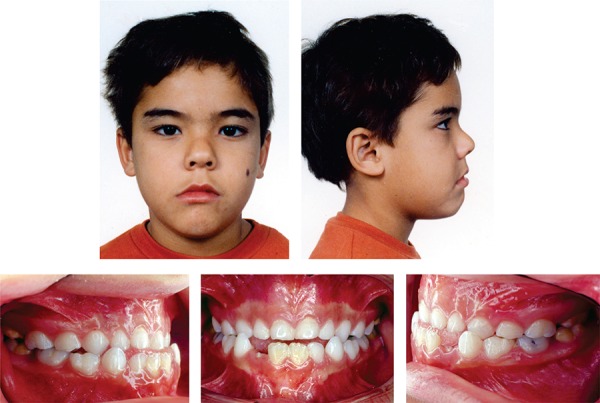

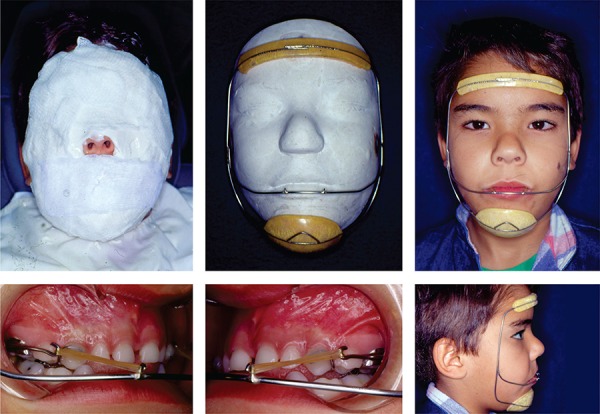

A 7.6-year old boy was referred to the clinic of the post-graduation program in Bauru School of Dentistry, University of São Paulo, for treatment. He presented a main facial symptom, due to an asymmetric mandible, shifted to the right. The nasolabial angle was increased and the poor development of the zygomatic region suggested a maxillary deficiency (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Extra-oral and Intraoral pretreatment photographs. Parents authorized the publication of these pictures.

The intraoral exam showed that the patient was in his mixed dentition stage with an anterior crossbite, with no deviation of centric occlusion to the centric relation. The terminal plan of primary second molars exhibited a mesial-step, with the left side presented canines in a crossbite relationship (Figure 1).

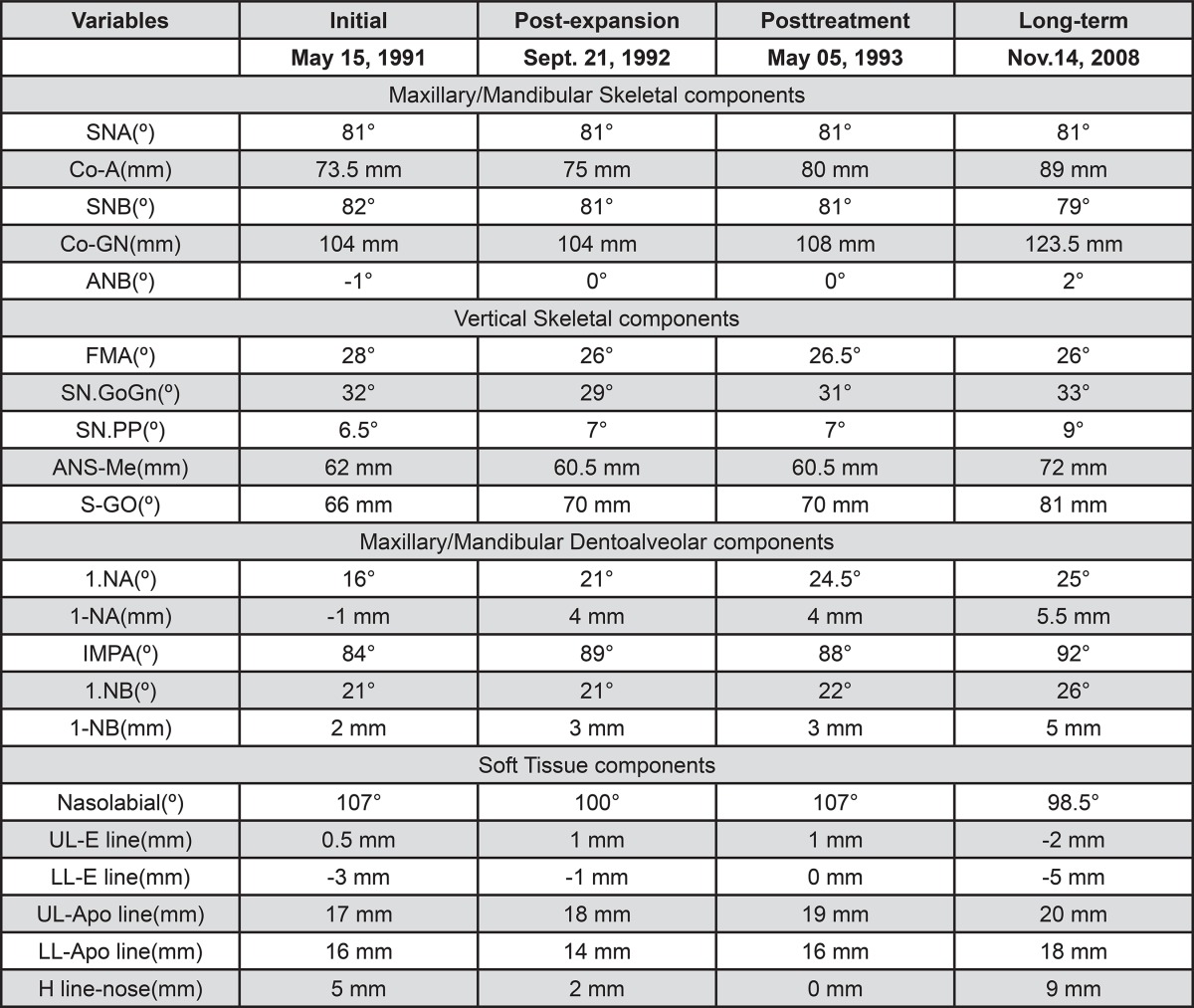

The panoramic radiograph showed no missing teeth and no pathologies. The cephalometric analysis (Figure 10) demonstrated the maxilla to be lightly retracted (SNA: 81°) and the mandible to be protruded (SNB: 82°). Therefore, they presented a deficient relationship between them (ANB: -1°). The mean value for ANB angle, at age seven, is 5° 18 .

Figure 10. Cephalometric analysis.

Dimensionally, the maxilla, when associated with the Nperp-A line and the nasolabial angle, presented a reduced length (Co-A). Thus, according to McNamara 19 (1984) the mandible (Co-Gn) and the low anterior face height (ANS to Me) showed to be increased; nevertheless, the facial appearance did not evidence this fact.

By assessing the main variables of the vertical skeletal component (SN.GoGn. FMA and S-Go), it was seen that the patient presented a good vertical growth pattern. The upper and lower incisors were markedly retruded and tipped to the lingual side; the soft tissue (H line-Nose, nasolabial angle) presented a concave profile (Figure 10).

Treatment objectives and alternatives

Through clinical data, radiographs and dental models, it was verified that the patient presented Class III malocclusion with anterior crossbite, due to maxillary lightly retracted, mandibular protrusion and good skeletal pattern.

A treatment alternative consists of a chincup used only at night and the Eschler appliance, also known as “progenic appliance”, used during the day. The treatment chosen was rapid maxillary expansion and facemask therapy. This protocol restores facial aesthetics and dental relationship, by providing occlusion stability.

Treatment progress

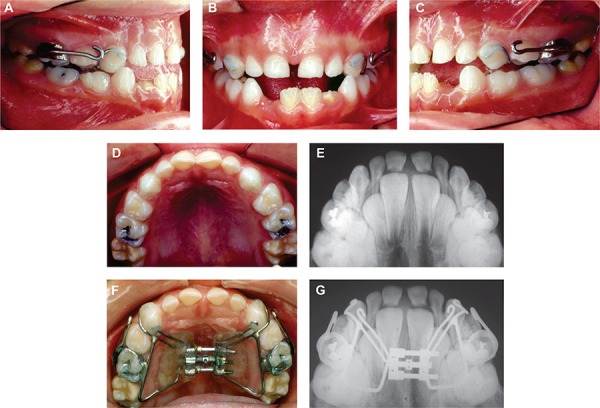

The treatment was performed after the signing of the Informed Consent Form by the parents. Initially, a modified Haas expander appliance was installed and, twenty four hours following expander cementation, the activation was started with 4/4 turns. The next day, the activations were performed with 2/4 turns in the morning and 2/4 in the evening (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Intraoral photograph before (A, B, C, D and E) and after expansion (F and G).

Fifteen days after activation, a midline diastema was observed, and the occlusal radiographs showed the rupture of the mid-palatal suture (Figure 2).

During the activation phase, the patient’s face was molded so that a modified Facemask 27 was made (Figure 3). Soon after palatine suture opening, the screw was splinted with acrylic resin and the facemask fitted to begin the maxillary protraction, through 5/16-inch bilateral elastics with a 200 g force in the first seven days, after which the force was increased to 500 g. The patient was required to wear the mask for 20 hours a day.

Figure 3. Photographs of the construction and adaptation of Turley´s face mask. Parents authorized the publication of these pictures.

Following a 3-month retention, so as to provide the necessary bone formation in the mid-palatal suture, the expander was removed and a new molding was performed to construct a removable retention appliance, with Adams’ clamps in the first permanent premolars, “C” clamps in primary canines and a wire welded to the horizontal bar of the Adams’ clamps, running up buccally to the primary canines region, with a hook for elastics fitting. Furthermore, the occlusal portion and the occlusal-buccal third of the posterior teeth were covered with a resin so as to enhance the retention of the appliance.

Six months posttreatment, the anteroposterior dental relationship showed to be satisfactory. However, since the patient presented lingual interposition in the anterior region, a new acrylic appliance with a palatine grid was made (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Removable appliance with grid palate.

The facemask was used 20 hours a day, for 10 months, after which the patient was requested to use it only at night, and use the acrylic appliance with a palatine grid 24 hours a day. Six months later, a satisfactory relationship in the anteroposterior plane and a mild improvement in the vertical one were observed. The patient was told not to use the mask and the retention plate was kept, aiming at the overall correction of the vertical plane, since the incisors were erupting.

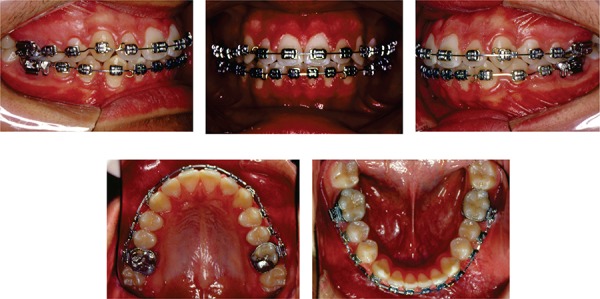

Due to the lack of space for the eruption of the left upper canine, in the final phase of the mixed denture, the patient was treated with an edgewise fixed appliance. Leveling and alignment were performed and the open coil springs were used to create space (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Orthodontic fixed appliance.

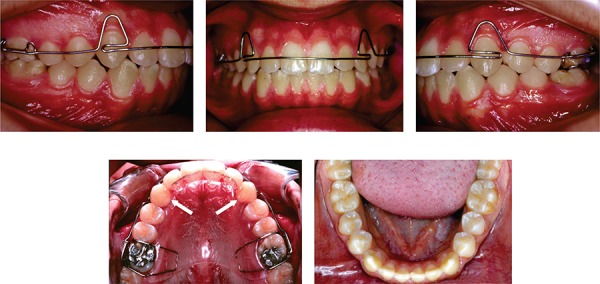

The treatment was completed in 2 years, and a modified Hawley retainer was inserted (Figure 6) for lingual crown torque of the upper canine’s crowns. For this torque to be performed, it is necessary to wear the acrylic resin, keeping a contact point with the canines’ cervical lingual face, and activating the vestibular arch, resulting in the tipping of the crown to the lingual side and the root, buccally.

Figure 6. Modified Hawley retainer.

Treatment results

The treatment was finished with the fixed appliance so as to level and align the teeth. The mandibular incisors were slightly modified and the maxillary incisors that had been markedly tipped to the lingual side and retruded, now were tipping to the buccal side and protruded (Figure 7 and Figure 10).

Figure 7. Intraoral posttreatment photographs.

Following the treatment, functional occlusion was obtained with anterior guide and lateral and protrusion movements, with satisfactory canines and molars relationships. The facial asymmetry improved with the dental alveolar correction.

The 15-year follow-up intraoral photographs show the stability of the treatment with the canines and molars in occlusion (Figure 8). The cephalometric evaluation of the patient presented a slight tendency to vertical growth, with an increased low anterior face height (ANS-Me).

Figure 8. Extra-oral and Intraoral long-term posttreatment photographs. Parents authorized the publication of these pictures.

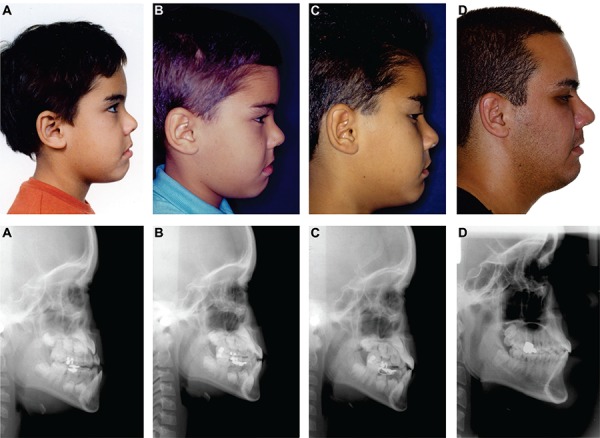

The anteroposterior relationship showed that the mandible (SNB and Co-Gn) did not change. On the other hand, the maxilla (Co-A) responded positively to the rapid maxillary expansion, associated to maxillary protraction (Figure 9 and Figure 10). There was an improvement in the maxillomandibular relationship, observed by the change in ANB angle (from -1° to 0).

Figure 9. Photographs and lateral radiographs. Parents authorized the publication of these pictures.

Due to the maxillary skeletal change, the soft tissue showed considerable improvement, observed clinically and cephalometrically. The H line-nose variable decreased from 5 mm to 2 mm and the nasolabial angle went from 107° to 100° (Figure 9 and Figure 10).

The cephalometric analysis, 15 years posttreatment, showed significant changes in the length of the maxilla and mandible (Co-A: +9 mm and Co-Gn: +15.5 mm). The overjet and overbite were stable, with the ANB angle reaching a good relation (ANB: 2°).

DISCUSSION

The goals were accomplished through orthopedic treatment of the Class III malocclusion associated with anterior crossbite by using rapid maxillary expansion and the facial mask. This approach is highly recommended for patients in their mixed and primary dentitions 4 , 20 , 27 and showed to be stable 15 years posttreatment.

The effects of maxillary protraction in different ages (deciduous, mixed, and late mixed dentition) did not show statistically significant results 25 . On the other hand, Baccetti, et al. 4 (1998) assessed two different age groups using maxillary expanders and facial masks, and noticed a significantly greater advance of the maxillary structures in the younger group. The increase might have occurred due to the rapid maxillary expansion, prior to the facial mask 3 .

Besides correcting the posterior crossbite, this expansion promoted the partial disarticulation of the maxilla at its suture level, providing cellular activity stimulation in these areas, improving the orthopedic action of maxillary protraction forces. Furthermore, this previous expansion prevented the anterior maxillary constriction, which might take place during maxillary protraction 10 , 11 , 15 , 27 .

In order to minimize counterclockwise maxillary rotation, the hooks for the elastics were placed in the upper canines’ region 7 , 12 , 27 . Thus, a forward and downwards maxillary displacement was achieved, generating a lower rotation 16 .

The intensity of the maxillary protraction force, as well the facial mask’s daily use time, differs according to several researchers 7 , 11 - 13 , 20 , 21 , 27 , 30 , ranging from 500 to 2,000 grams. However, a lower intensity force in the beginning of the treatment, around 150 to 200 grams, which was gradually increased to 550 grams, allowed the patient to adapt to the facial mask.

The lower teeth maintained their tipping during the control period with no retainers. The treatment involving lower incisors lingual tipping is more deleterious, and may present relapse and gingival recession at long term posttreatment evaluations.

The cephalometric analysis demonstrated an increase of the ANB angle and mandible growth. This case initially demonstrated a Co-A measurement of 73.5 mm, and Co-Gn 104 mm. However, at the last follow-up appointment, Co-A was 89 mm, and Co-Gn 123.5 mm, which has been considered appropriate.

Regarding the soft tissues, the convexity angle diminished during the treatment, providing facial aesthetics and optimal labial posture. This decrease is attributed, mainly, to changes in the mandibular angle plane 17 . In the long term posttreatment, this angle increased, the nasolabial angle decreased, and the upper lip tended to retract.

Retainers are extremely important following Class III orthopedic treatment, in order to prevent a future surgical intervention. Class III is not considered definitely treated until growth is fully achieved. Relapse is related to the changes in the dental tippings and maxillary rotation, following the first month of facial mask interruption 10 . Some authors claim that the longer it takes for stability to be rated, the more relapse is verified 9 , 23 .

The experimental study showed that stability is proportional to the amount of time the retainers are used for 15 and the clinical researches show that the facemask must be kept till the end of mandibular growth 7 . Balters’ Bionator for Class III or Fränkel´s FR III can be used for retention for 3 to 12 months 20 , 27 , associated with the nocturnal chincup until the end of the growth.

The researches on rapid maxillary expansion associated with facemask assess only a short period of time posttreatment 8 , 22 . Turley 28 (2002) claimed that this protocol does not normalize growth and that, in the posttreatment time, the Class III pattern growth returns, mainly in maxillary growth deficiency. Gallagher, et al. 8 (1998), concluded that, in the posttreatment time, the mandible returned to the normal growth of this malocclusion, downwards and forwards.

The Class III treatment overcorrection helps controlling the disproportional growth between the maxilla and the mandible. The increase of the overjet and the buccal crown torque of the upper incisors reduce the relapse; therefore, the overcorrection must always be achieved during the pubertal growth, a period when the mandibular growth is greater than the maxillary one 29 .

The occlusal intercuspation allowed the maxilla to follow the mandibular growth. Thus, the dental corrections presented skeletal benefits, contributing to the occlusion stability 2 . Therefore, the early treatment provided a good occlusal relation for the normal maxillary growth, promoting long-term posttreatment stability.

CONCLUSION

This case report shows the stability of an early Class III malocclusion treatment by using a maxillary expansion and facemask therapy, 15 years posttreatment. Growing patients should be monitored following their treatment, so as to prevent malocclusion relapse.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almeida MR, Almeida RR, Oltramari-Navarro PV, Conti AC, Navarro RL, Camacho JG. Early treatment of Class III malocclusion: 10-year clinical follow-up. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19(4):431–439. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572011000400022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson I, Rabie AB, Wong RW. Early treatment of pseudo-class III malocclusion: a 10-year follow-up study. J Clin Orthod. 2009;43(11):692–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baccetti T, McGill JS, Franchi L, McNamara JA, Jr, Tollaro I. Skeletal effects of early treatment of Class III malocclusion with maxillary expansion and face-mask therapy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;113(3):333–343. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70306-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baccetti T, Tollaro I. A retrospective comparison of functional appliance treatment of Class III malocclusions in the deciduous and mixed dentitions. Eur J Orthod. 1998;20(3):309–317. doi: 10.1093/ejo/20.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns NR, Musich DR, Martin C, Razmus T, Gunel E, Ngan P. Class III camouflage treatment: what are the limits? Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137(1) doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.05.017. 9 e1-9 e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casko JS, Shepherd WB. Dental and skeletal variation within the range of normal. Angle Orthod. 1984;54(1):5–17. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1984)054<0005:DASVWT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cozzani G. Extraoral traction and class III treatment. Am J Orthod. 1981;80(6):638–650. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(81)90266-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallagher RW, Miranda F, Buschang PH. Maxillary protraction: treatment and posttreatment effects. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;113(6):612–619. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardner SD, Chaconas SJ. Posttreatment and postretention changes following orthodontic therapy. Angle Orthod. 1976;46(2):151–161. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1976)046<0151:PAPCFO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.GekKiow G, Kaan SK. Dentofacial orthopaedic correction of maxillary retrusion with the protraction facemask - a literature review. Aust Orthod J. 1992;12(3):143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hata S, Itoh T, Nakagawa M, Kamogashira K, Ichikawa K, Matsumoto M, et al. Biomechanical effects of maxillary protraction on the craniofacial complex. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987;91(4):305–311. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(87)90171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hickham JH. Maxillary protraction therapy: diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Orthod. 1991;25(2):102–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irie M, Nakamura S. Orthopedic approach to severe skeletal Class III malocclusion. Am J Orthod. 1975;67(4):377–392. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(75)90020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishii H, Morita S, Takeuchi Y, Nakamura S. Treatment effect of combined maxillary protraction and chincap appliance in severe skeletal Class III cases. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987;92(4):304–312. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(87)90331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itoh T, Chaconas SJ, Caputo AA, Matyas J. Photoelastic effects of maxillary protraction on the craniofacial complex. Am J Orthod. 1985;88(2):117–124. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(85)90235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kambara T. Dentofacial changes produced by extraoral forward force in the Macaca irus. Am J Orthod. 1977;71(3):249–277. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(77)90187-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin J, Gu Y. Preliminary investigation of nonsurgical treatment of severe skeletal Class III malocclusion in the permanent dentition. Angle Orthod. 2003;73(4):401–410. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2003)073<0401:PIONTO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martins DR, Janson G, Almeida RR, Pinzan A, Henriques JF, Freitas MR. Atlas de crescimento craniofacial. Säo Paulo: Santos; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNamara JA., Jr A method of cephalometric evaluation. Am J Orthod. 1984;86(6):449–469. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9416(84)90352-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNamara JA., Jr An orthopedic approach to the treatment of Class III malocclusion in young patients. J Clin Orthod. 1987;21(9):598–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nanda R. Biomechanical and clinical considerations of a modified protraction headgear. Am J Orthod. 1980;78(2):125–139. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(80)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ngan PW, Hagg U, Yiu C, Wei SH. Treatment response and long-term dentofacial adaptations to maxillary expansion and protraction. Semin Orthod. 1997;3(4):255–264. doi: 10.1016/s1073-8746(97)80058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadowsky C, Sakols EI. Long-term assessment of orthodontic relapse. Am J Orthod. 1982;82(6):456–463. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugawara J, Mitani H. Facial growth of skeletal Class III malocclusion and the effects, limitations, and long-term dentofacial adaptations to chincap therapy. Semin Orthod. 1997;3(4):244–254. doi: 10.1016/s1073-8746(97)80057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sung SJ, Baik HS. Assessment of skeletal and dental changes by maxillary protraction. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;114(5):492–502. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Troy BA, Shanker S, Fields HW, Vig K, Johnston W. Comparison of incisor inclination in patients with Class III malocclusion treated with orthognathic surgery or orthodontic camouflage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135(2): doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turley PK. Orthopedic correction of Class III malocclusion with palatal expansion and custom protraction headgear. J Clin Orthod. 1988;22(5):314–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turley PK. Managing the developing Class III malocclusion with palatal expansion and facemask therapy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2002;122(4):349–352. doi: 10.1067/mod.2002.127295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westwood PV, McNamara JA, Jr, Baccetti T, Franchi L, Sarver DM. Long-term effects of Class III treatment with rapid maxillary expansion and facemask therapy followed by fixed appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;123(3):306–320. doi: 10.1067/mod.2003.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wisth PJ, Tritrapunt A, Rygh P, Bøe OE, Norderval K. The effect of maxillary protraction on front occlusion and facial morphology. Acta Odontol Scand. 1987;45(3):227–237. doi: 10.3109/00016358709098862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]