Abstract

Reactive nitrogen species (RNS) generated after exposure to radiation have been implicated in lung injury. Surfactant protein D (SP-D) is a pulmonary collectin that suppresses inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)-mediated RNS production. Herein, we analyzed the role of iNOS and SP-D in radiation-induced lung injury. Exposure of wild-type (WT) mice to γ-radiation (8 Gy) caused acute lung injury and inflammation, as measured by increases in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) protein and cell content at 24 h. Radiation also caused alterations in SP-D structure at 24 h and 4 weeks post exposure. These responses were blunted in iNOS−/− mice. Conversely, loss of iNOS had no effect on radiation-induced expression of phospho-H2A.X or tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Additionally, at 24 h post radiation, cyclooxygenase expression and BAL lipocalin-2 levels were increased in iNOS−/− mice, and heme oxygenase (HO)-1+ and Ym1+ macrophages were evident. Loss of SP-D resulted in increased numbers of enlarged HO-1+ macrophages in the lung following radiation, along with upregulation of TNF-α, CCL2, and CXCL2, whereas expression of phospho-H2A.X was diminished. To determine if RNS play a role in the altered sensitivity of SP-D−/− mice to radiation, iNOS−/–/SP-D–/– mice were used. Radiation-induced injury, oxidative stress, and tissue repair were generally similar in iNOS–/–/SP-D–/– and SP-D–/– mice. In contrast, TNF-α, CCL2, and CXCL2 expression was attenuated. These data indicate that although iNOS is involved in radiation-induced injury and altered SP-D structure, in the absence of SP-D, it functions to promote proinflammatory signaling. Thus, multiple inflammatory pathways contribute to the pathogenic response to radiation.

Keywords: radiation, lung injury, surfactant protein D, iNOS, reactive nitrogen species

Pulmonary complications following exposure to ionizing radiation include acute lung injury and pneumonitis, which can progress to fibrosis (Medhora et al., 2012; Movsas et al., 1997). Evidence suggests that this involves a cascade of inflammatory events lasting from weeks to months (Ding et al., 2013; Movsas et al., 1997). Reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and proinflammatory cytokines, released in large part by inflammatory macrophages, have been implicated in radiation-induced pulmonary injury and fibrosis (Giaid et al., 2003; Nozaki et al., 1997; Pietrofesa et al., 2013; Tsuji et al., 2000). Of particular interest are RNS, including nitric oxide and its oxidation products. These reactive molecules are known to induce membrane lipid peroxidation, nitration, and hydroxylation of aromatic amino acid residues, as well as sulfhydryl oxidation of proteins (Nozaki et al., 1997). Nitric oxide is generated in macrophages from l-arginine via inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), a calcium-independent enzyme upregulated during inflammation (Laskin et al., 2010). Findings that iNOS inhibitors including aminoguanidine and N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester attenuate radiation-induced lung injury demonstrate that RNS are important in the pathogenic response (Nozaki et al., 1997; Tsuji et al., 2000).

Surfactant protein-D (SP-D) is a pulmonary collectin synthesized mainly by alveolar type II cells and its interactions with RNS are critical in regulating macrophage activation (Atochina et al., 2004; Yoshida and Whitsett, 2006). SP-D has been shown to inhibit lung macrophage proinflammatory activity by suppressing the transcription factor nuclear factor (NF)-κB, a key regulator of iNOS expression (Yoshida and Whitsett, 2006). Conversely, SP-D that has been nitrosylated by RNS is a proinflammatory activator of macrophages (Guo et al., 2008). Loss of SP-D has been reported to result in chronic pulmonary inflammation, characterized by increased numbers of activated macrophages in the lung and upregulation of iNOS, with concomitant oxidative stress (Botas et al., 1998; Groves et al., 2012). Alveolar macrophages isolated from SP-D−/− mice also express increased levels of iNOS and generate more nitric oxide (Atochina et al., 2004). As a consequence, SP-D−/− mice are highly sensitive to pulmonary irritants such as ozone and bleomycin, which are known to induce injury via the generation of RNS (Aono et al., 2012; Groves et al., 2012, 2013). Reports that inhibition of iNOS reduces pulmonary inflammation and injury in SP-D−/− mice support the notion that RNS mediate lung injury in the absence of SP-D (Atochina-Vasserman et al., 2007). Based on these observations, we hypothesized that radiation-induced injury would be increased in the lungs of SP-D−/− mice, and that RNS contribute to this response. To test this hypothesis, we used transgenic mice lacking the SP-D gene, Sftpd, the iNOS gene, NOS2, or both of these genes. We found that radiation-induced lung injury is associated with iNOS-dependent acute lung injury, inflammation, and disruption of SP-D dodecamer structure. However, in the absence of SP-D, the role of iNOS is limited to promoting inflammatory mediator signaling. Taken together, these findings indicate that the response to lung injury following radiation exposure involves interplay between multiple inflammatory pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and treatments

Specific pathogen-free (8–14 weeks) C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice and iNOS−/− mice, bred on C57BL/6 background, were obtained from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). C57BL/6 mice with a targeted disruption of Sftpd (SP-D−/−) (Botas et al., 1998) and iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− double knockout mice (Knudsen et al., 2014) were bred at the Rutgers University animal facility. All animals were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in microisolation cages and provided food and water ad libitum. Animals received humane care in compliance with the institution's guidelines, as outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the National Institutes of Health. Total body irradiation (8 Gy) was performed using a 137Cs γ-ray source (Radiation Machinery Corp., Parsippany, NJ) operating at a dose rate of 2 Gy/min. Both male and female mice were used in our studies; no significant differences were observed in their responses to radiation.

Bronchoalveolar lavage and tissue collection

Animals were sacrificed 6 h, 24 h, or 4 weeks after radiation exposure by intraperitoneal injection of Nembutal (250 mg/kg). Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) was collected and cell and protein content assayed as previously described (Groves et al., 2012). Differential analysis was performed on Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations. For histological sections, the left lobe of the lung was perfused with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS, removed and fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C, and then transferred to 50% ethanol. The remaining lung lobes were removed, immersed in RNAlater (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Western blot analysis

BAL proteins were separated using native and reducing gel electrophoresis as previously reported (Atochina-Vasserman et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2008). Briefly, denatured and native aliquots of BAL proteins were fractionated on denaturing 4–12% Novex Bis–Tris gels or 4–16% Bis–Tris NativePAGE gels (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA), respectively, and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation of the blots with 10% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were then incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-lipocalin-2 antibody (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA; 1:500), rabbit polyclonal anti-SP-D antibody DU117 (a gift from Dr. Amy Pastva, Duke University, NC; 1:10 000), or a mixture of rabbit polyclonal anti-SP-D antibody DU117 (1:10 000), and rabbit polyclonal anti-SP-D antibody from Chemicon (Billerica, MA; 1:4000), washed and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000) diluted in Tris-buffered saline/Tween-20. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system (GE Healthcare Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software developed by National Institute of Health.

Immunohistochemistry

Lung sections (5 μm) were deparaffinized and endogenous peroxidase quenched using 3% hydrogen peroxide diluted in methanol. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling the specimens for 10 min in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 0.05% Tween-20. To block nonspecific binding, sections were incubated for 1–2 h at room temperature in Tris-buffered saline/Tween-20 containing goat serum. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber with rabbit polyclonal anti-heme oxygenase (HO)-1 antibody (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI; 1:1000), anti-cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 antibody (Abcam Inc., 1:2500), anti-Ym1 antibody (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada; 1:300), or rabbit monoclonal antiphospho-histone H2A.X antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA; 1:400), or appropriate IgG controls. Sections were then rinsed and incubated at room temperature for 30 min with biotinylated secondary antibody (Vectastain Elite ABC kit, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Binding was visualized using an avidin-biotinylated enzyme complex (Vectastain Elite ABC kit) with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as the substrate (Vector Labs).

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR

Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). The quantity and quality of RNA were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Inc., Wilmington, DE). mRNA was reverse transcribed using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. PCR primers were generated using Primer Express 3.0 software (Applied Biosystems) and synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Standard curves were generated using serial dilutions of randomly selected and pooled cDNA samples. Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 7300 real-time PCR system. Forward and reverse primers used were: lipocalin-2 (24p3), AGG AAC GTT TCA CCC GCT TT and TGT TGT CGT CCT TGA GGC C; tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, AGG GAT GAG AAG TTC CCA AAT G and TGT GAG GGT CTG GGC CAT A; CCL2, TTG AAT GTG AAG TTG ACC CGT AA and GCT TGA GGT TGT GGA AAA G; CXCL2, AGG CTT CCC GAT GAA GAG and CAG GAT AAG AGC GAG AGC CTA CA; and GAPDH, TGA AGC AGG CAT CTG AGG G and CGA AGG TGG AAG AGT GGG AG.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism V6.01 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or unpaired t test (unequal variance) was used to test differences between groups. Immunohistochemistry data were assessed nonparametrically using the Kruskal–Wallis test. A P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effects of Radiation on Markers of Lung Injury and Inflammation

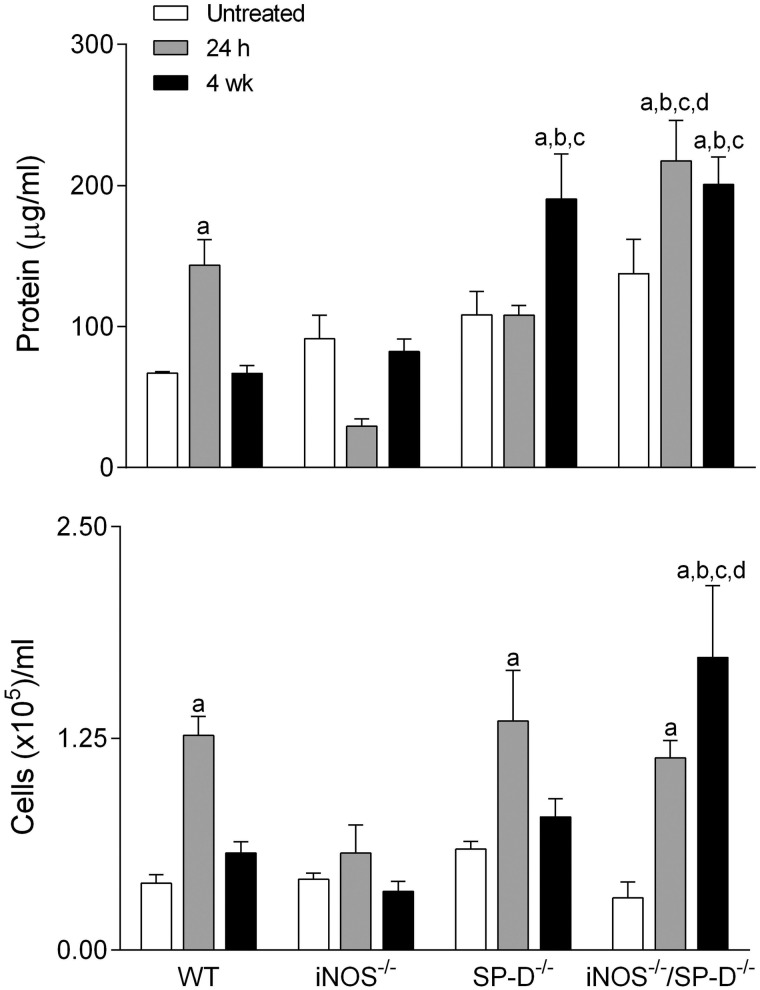

Initially, we analyzed the effects of radiation exposure on lung injury and inflammation, as measured by BAL protein and cell content (Bhalla, 1999). BAL from untreated WT control mice contained low levels of protein and cells (Fig. 1). Radiation exposure resulted in increases in BAL protein and cell content at 24 h; however, by 4 weeks, levels were similar to untreated control (Fig. 1). Differential analysis revealed that the majority of BAL cells (>98%) were macrophages in both control and radiation-exposed mice.

FIG. 1.

Effects of radiation exposure on BAL protein and cell content. BAL was collected from untreated mice or 24 h and 4 weeks (wk) after exposure of WT, iNOS−/−, SP-D−/−, and iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice to radiation, and analyzed for protein (upper panel) or cell content (lower panel). Each bar is the mean ± SE (n = 3–6 mice/treatment group). aSignificantly (P ≤ 0.05) different from respective untreated mice; bSignificantly (P ≤ 0.05) different from WT mice at the same post exposure time point; cSignificantly (P ≤ 0.05) different from iNOS−/− mice at the same post exposure time point; dSignificantly (P ≤ 0.05) different from SP-D−/− mice at the same post exposure time point.

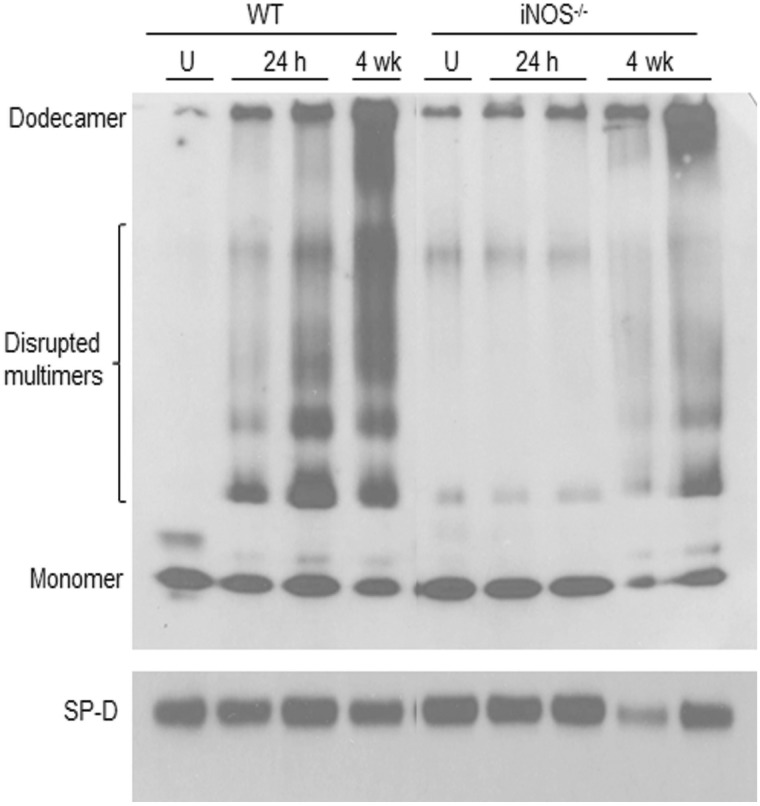

To determine if radiation-induced lung inflammation was associated with alterations in SP-D activity, we analyzed its oligomeric state in BAL by native gel electrophoresis. The secreted form of SP-D is assembled into large cruciform dodecamers composed of a tetramer of trimers that do not readily migrate in native gels (Guo et al., 2008). Consistent with this observation, we found no major bands of SP-D in BAL from unexposed WT mice (Fig. 2, upper panel). Following radiation exposure, multiple lower molecular weight forms of SP-D were detected at 24 h and 4 weeks. INOS-derived RNS have previously been shown to disrupt SP-D structure (Atochina-Vasserman, 2012). To assess whether RNS derived from iNOS mediates radiation-induced disruption of SP-D structure, we used iNOS−/− mice. In radiation-exposed iNOS−/− mice, the appearance of disrupted SP-D dodecamers in BAL was reduced relative to WT mice (Fig. 2). This was associated with a reduction in radiation-induced increases in BAL protein and cell content to control levels (Fig. 1).

FIG. 2.

Effects of radiation exposure on BAL SP-D structure. SP-D protein was analyzed in BAL collected from untreated (U) mice or 24 h and 4 weeks (wk) after exposure of WT and iNOS−/− mice to radiation. Upper panel, SP-D protein analyzed in native gels; Lower panel, SP-D protein analyzed in denatured gels.

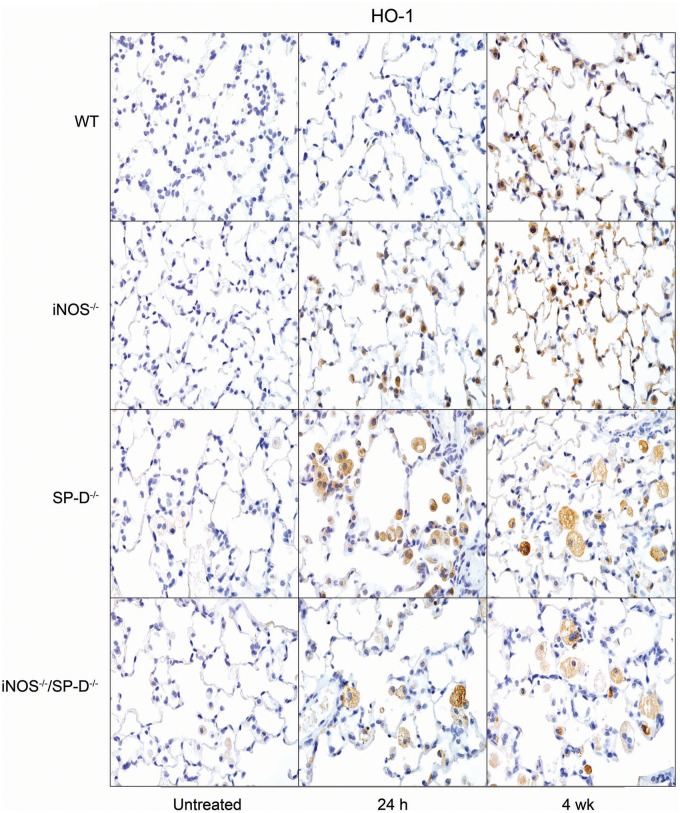

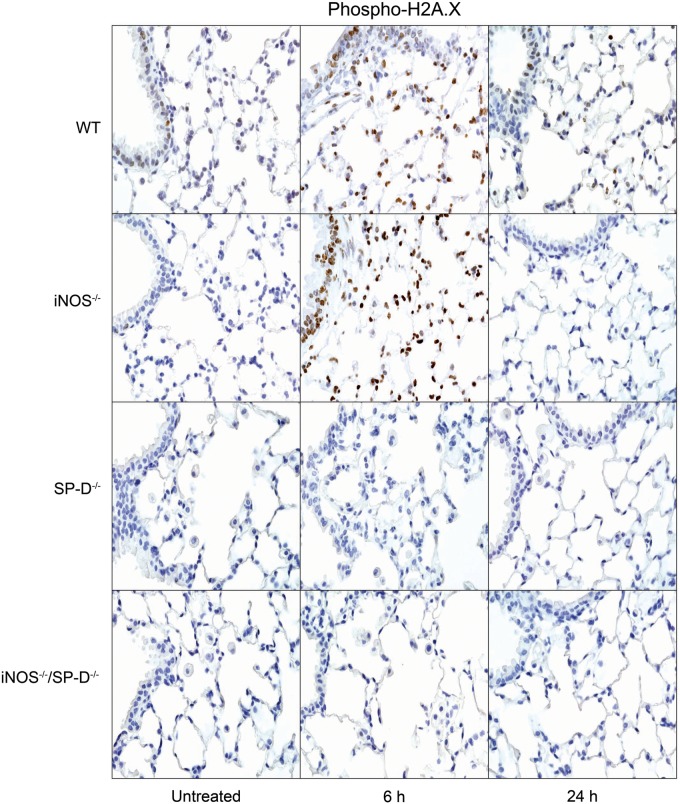

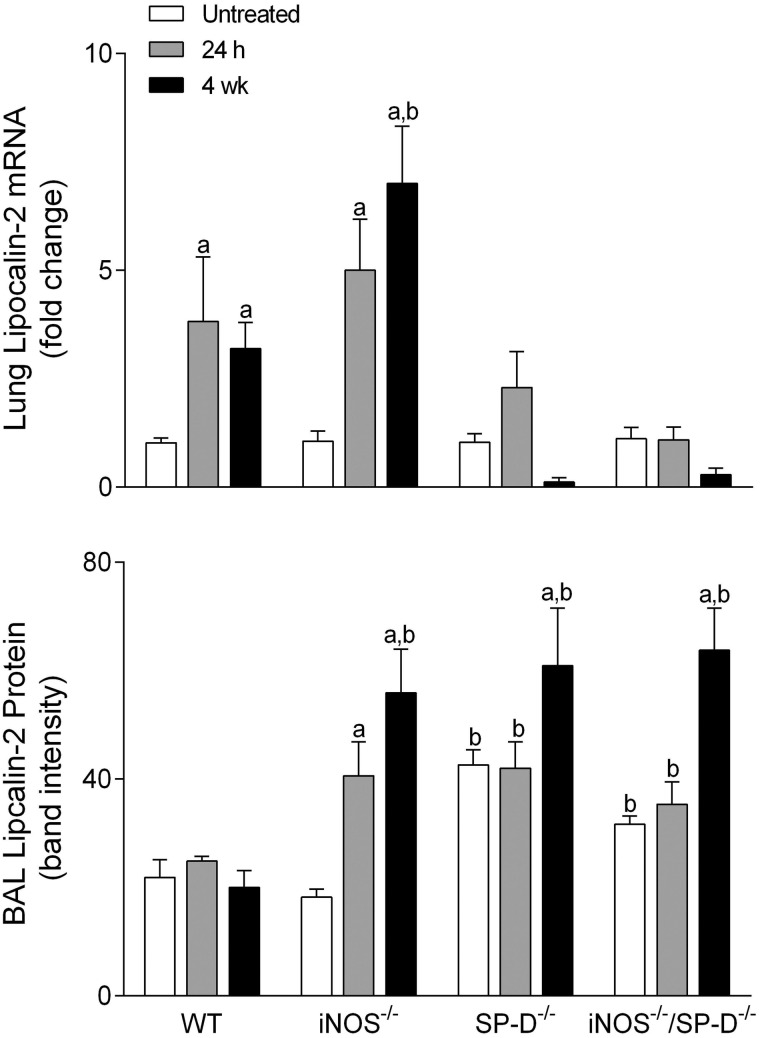

Exposure of WT mice to radiation was also found to induce oxidative stress, as measured by increased expression of HO-1 in lung macrophages and epithelial cells at 4 weeks (Fig. 3). In iNOS−/− mice, increases in HO-1+ macrophages were more rapid (<24 h post radiation). In contrast, loss of iNOS had no effect on radiation-induced increases in phospho-H2A.X, a marker of repair of double-strand DNA damage (Banath and Olive, 2003), which was evident 6 h post exposure (Fig. 4). Lipocalin-2 is an acute phase protein upregulated in response to oxidative stress; it is thought to play a role in the resolution of tissue injury by scavenging ROS (Dittrich et al., 2013; Roudkenar et al., 2007, 2008; Warszawska et al., 2013). We found that lipocalin-2 mRNA increased as early as 24 h after radiation (Fig. 5, upper panel). While loss of iNOS had no effect on this response at 24 h, at 4 weeks post radiation exposure, lipocalin-2 mRNA levels were elevated relative to WT mice. Additionally, in iNOS-/- mice, but not in WT mice, lipocalin-2 protein levels in BAL were significantly increased 24 h post radiation exposure and this was maintained for at least 4 weeks (Fig. 5, lower panel).

FIG. 3.

Effects of radiation exposure on lung HO-1 expression. Lung sections, prepared from untreated mice or 24 h and 4 weeks (wk) after exposure of WT, iNOS−/−, SP-D−/−, and iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice to radiation, were stained with antibody to HO-1. Binding was visualized using a Vectastain kit. Original magnification, 600×. Representative sections from 3 mice/treatment group are shown.

FIG. 4.

Effects of radiation exposure on lung cell DNA damage. Lung sections, prepared from untreated mice or 6 h and 24 h after exposure of WT, iNOS−/−, SP-D−/−, and iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice to radiation, were stained with antibody to phospho-H2A.X. Binding was visualized using a Vectastain kit. Original magnification, 600×. Representative sections from 3 mice/treatment group are shown.

FIG. 5.

Effects of radiation exposure on lung lipocalin-2. BAL and lungs were collected from untreated mice or 24 h and 4 weeks (wk) after exposure of WT, iNOS−/−, SP-D−/−, and iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice to radiation. Upper panel, Total RNA was isolated from lung tissue, reverse-transcribed, and mRNA analyzed by real-time PCR as described in the Materials and Methods section. Data are presented as fold change from untreated WT control. Lower panel, BAL protein was analyzed by western blotting for expression of lipocalin-2. Protein band intensity was quantified using ImageJ software. Bars are the mean ± SE (n = 3 mice/treatment group). aSignificantly (P ≤ 0.05) different from respective untreated group; bSignificantly (P ≤ 0.05) different from WT mice at the same post exposure time point.

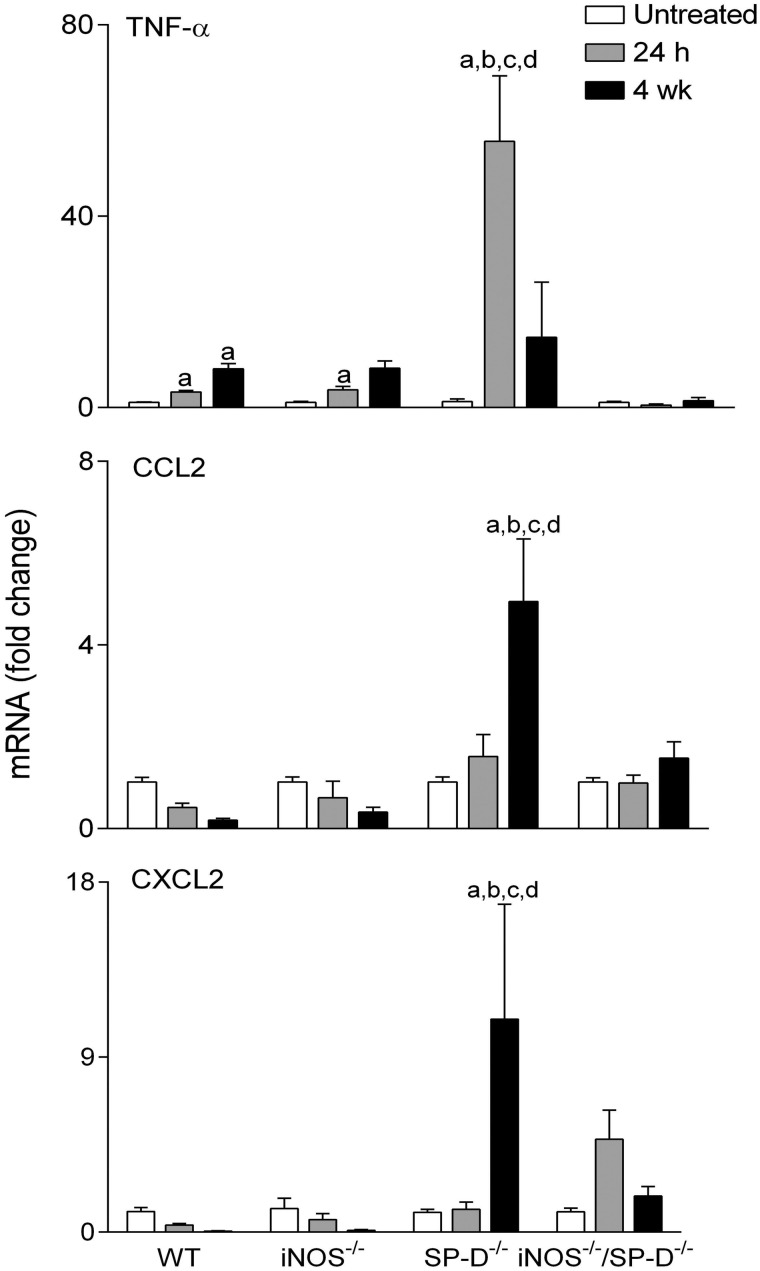

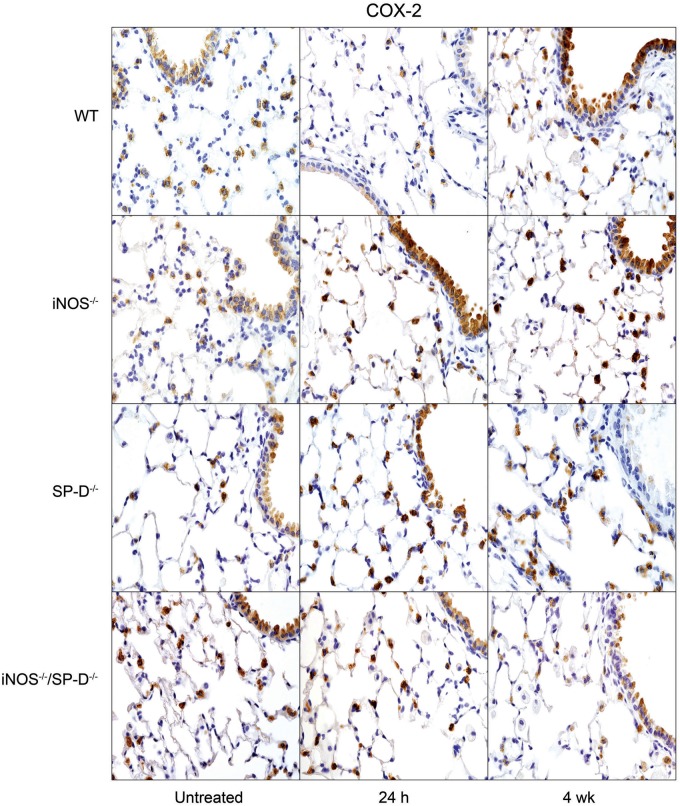

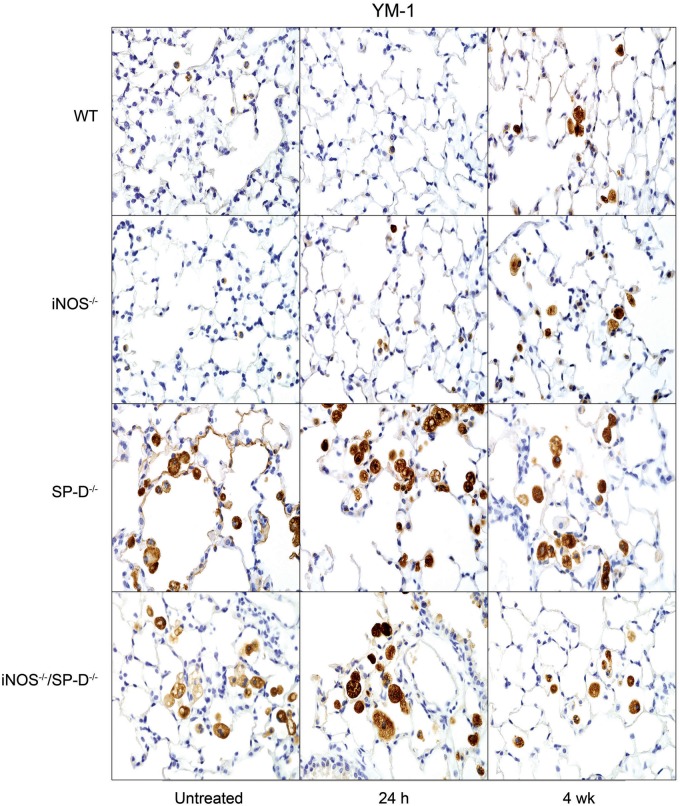

In further studies, we analyzed the effects of radiation on expression of proinflammatory proteins implicated in inflammatory pathologies including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, acute lung injury, and fibrosis (Ao et al., 2009; Cachaco et al., 2010; Chai et al., 2013; Fox et al., 2011; Konrad and Reutershan, 2012; Rube et al., 2002, 2005; Russo et al., 2009). In WT mice, increases in TNF-α mRNA expression were observed at 24 h and 4 weeks post exposure (Fig. 6). Conversely, radiation had no significant effects on expression of the chemokines, CCL2, or CXCL2, and it caused a transient decrease in constitutive COX-2 expression in bronchial and type II epithelial cells (Figs. 6 and 7). However, at 4 weeks post radiation exposure, COX-2 expression was increased above control levels, mainly in the bronchial epithelium. Whereas loss of iNOS had no major effects on radiation-induced expression of TNF-α, CCL2, or CXCL2, COX-2 levels in type II cells were increased in iNOS-/- mice, relative to WT mice at 24 h and 4 weeks post exposure, and in bronchial epithelium at 24 h (Figs. 6 and 7). We also analyzed expression of Ym1 in the lung, a marker of antiinflammatory/profibrotic macrophages (Misson et al., 2004). Ym1+ macrophages were detected in the lungs of both WT and iNOS−/− mice at 4 weeks post radiation exposure. They were also observed in lungs of iNOS−/− mice 24 h post radiation exposure (Fig. 8); however, these cells were generally smaller and fewer in number than cells observed at 4 weeks.

FIG. 6.

Effects of radiation exposure on lung mRNA expression of proinflammatory mediators. Lungs were collected from untreated mice or 24 h and 4 weeks (wk) after exposure of WT, iNOS−/−, SP-D−/−, and iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice to radiation. Total RNA was isolated, reverse-transcribed, and mRNA analyzed by real-time PCR as described in the Materials and Methods section. Data are presented as fold change from untreated WT control. Each bar represents the mean ± SE (n = 3–5 mice/treatment group). aSignificantly (P ≤ 0.05) different from respective untreated group; bSignificantly (P ≤ 0.05) different from WT mice at the same post exposure time point; cSignificantly (P ≤ 0.05) different from iNOS−/− mice at the same post exposure time point; dSignificantly (P ≤ 0.05) different from iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice at the same post exposure time point.

FIG. 7.

Effects of radiation exposure on lung COX-2 expression. Lung sections, prepared from untreated mice or 24 h and 4 weeks (wk) after exposure of WT, iNOS−/−, SP-D−/−, and iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice to radiation, were stained with antibody to COX-2. Binding was visualized using a Vectastain kit. Original magnification, 600×. Representative sections from 3 mice/treatment group are shown.

FIG. 8.

Effects of radiation exposure on lung Ym1 expression. Lung sections, prepared from untreated mice or 24 h and 4 weeks (wk) after exposure of WT, iNOS−/−, SP-D−/−, and iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice to radiation, were stained with antibody to the alternatively activated/profibrotic macrophage marker, Ym1. Binding was visualized using a Vectastain kit. Original magnification, 600×. Representative sections from 3 mice/treatment group are shown.

Previous studies have demonstrated that ablation of the SP-D gene results in chronic pulmonary inflammation (Crouch, 2000). Since iNOS-dependent alterations in SP-D were observed following radiation exposure, in further studies we analyzed the effects of loss of SP-D on lung injury, inflammation, and oxidative stress. We found that radiation-induced increases in BAL protein were delayed in SP-D−/− mice, when compared with WT mice, with no differences in BAL cell content (Fig. 1). As observed in iNOS−/− mice, in SP-D−/− mice, radiation caused more rapid increases in HO-1+ macrophages in the lung relative to WT mice; additionally, these cells were larger and more vacuolated (Fig. 3). In SP-D−/− mice, this was correlated with a loss of radiation-induced phospho-H2A.X expression (Fig. 4). In contrast, greater levels of lipocalin-2 were observed in BAL from SP-D−/− mice, a response similar to iNOS−/− mice, but its expression in the tissue was reduced (Fig. 5). We also noted significant alterations in radiation-induced mRNA expression of inflammatory markers in lungs of SP-D−/− mice, when compared with WT mice. Thus, greater increases in TNF-α mRNA expression were evident 24 h post radiation exposure in SP-D−/− mice, whereas CCL2 and CXCL2 were increased at 4 weeks (Fig. 6). Expression of COX-2 was also greater in lungs of SP-D−/− mice, relative to WT mice at 24 h post radiation, whereas at 4 weeks it was reduced in the bronchial epithelium (Fig. 7). Loss of SP-D was associated with increased numbers of enlarged Ym1+ macrophages in the lungs of untreated mice (Fig. 8); radiation exposure had no significant effect on these cells.

Chronic pulmonary inflammation in SP-D−/− mice has been reported to be reduced by inhibition of iNOS or ablation of the NOS2 gene; moreover, this is associated with reduced sensitivity of SP-D−/− mice to lung toxicants (Atochina-Vasserman et al., 2007; Knudsen et al., 2014). To assess whether a similar response is observed after radiation exposure, we used iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− double knockout mice. Unexpectedly we found that radiation-induced increases in BAL protein content were significantly greater in iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice, when compared with WT mice and similar to or greater than SP-D−/− mice (Fig. 1). Radiation-induced increases in enlarged HO-1+ macrophages were also similar to those observed in SP-D−/− mice and phospho-H2A.X was undetectable (Figs. 3 and 4). As observed in SP-D−/− mice, lipocalin-2 mRNA was reduced to control levels in double knockout mice, whereas lipocalin-2 protein levels in BAL were elevated 4 weeks post radiation (Fig. 5). Conversely, radiation-induced upregulation of TNF-α, CCL2, and CXCL2 were attenuated in iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice, when compared with SP-D−/− mice (Fig. 6). Moreover, COX-2 expression in bronchial epithelium of iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice was reduced 24 h post exposure, whereas alveolar epithelial levels were similar (Fig. 7). We also noted Ym1+ macrophages in the lungs of untreated iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice and, as observed in SP-D−/− mice, radiation exposure had no major effect on these cells (Fig. 8).

DISCUSSION

Lung homeostasis is dependent on pulmonary collectins such as SP-D, which function to negatively regulate macrophage responses to foreign materials (Crouch, 2000). In the absence of SP-D, mice develop chronic pulmonary inflammation and display heightened sensitivity to toxicants, a response largely dependent on RNS generated via iNOS (Atochina-Vasserman, 2012; Matalon et al., 2009). The present studies demonstrate that radiation also causes iNOS-dependent alterations in the quaternary structure of SP-D. However, although ablation of the SP-D gene was associated with increases in the sensitivity of mice to radiation-induced lung injury, oxidative stress, and inflammatory mediator expression, only the latter response was dependent on iNOS. These results indicate that in the absence of SP-D, RNS generated via iNOS are an important component of radiation-induced inflammatory signaling. These studies and other investigations of the role of iNOS in radiation-induced pulmonary pathology (Nozaki et al., 1997; Tsuji et al., 2000), highlight the delicate balance that exists within the lung in terms of maintaining inflammatory homeostasis.

Injury to the alveolar epithelium results in an accumulation of albumin, fibrin and other plasma proteins, and inflammatory cells in alveolar regions of the lung (Bhalla, 1999). Consistent with acute alveolar injury, we observed increases in BAL protein and inflammatory cell content 24 h following exposure of WT mice to radiation. This was associated with alterations in SP-D dodecamer structure. Evidence suggests that disruption of SP-D quaternary structure is accompanied by nonreducible covalent crosslinking; moreover, the presence of cross-linked SP-D is directly related to disease severity (Atochina-Vasserman et al., 2011). Cross-linked SP-D has been observed in patients with acute allergy or gastroesophageal reflux disease, and in preterm infants at risk of developing chronic lung disease (Atochina-Vasserman et al., 2011; Griese et al., 2002; Kotecha et al., 2013). Alterations in SP-D structure are thought to be important in the pathogenesis of these diseases, and they may also contribute to radiation-induced lung injury. Our findings that disruption of SP-D structure by radiation is reduced in iNOS−/− mice are consistent with reports describing its dependence on RNS (Atochina-Vasserman et al., 2011). We also found that increases in BAL protein and cell content following radiation exposure were reduced in iNOS−/− mice. A similar attenuation of radiation-induced increases in BAL protein, as well as lactate dehydrogenase activity, has been described in mice treated with the iNOS inhibitor, aminoguanidine (Tsuji et al., 2000). These findings suggest a role of RNS in alveolar epithelial barrier dysfunction. Radiation exposure also resulted in oxidative stress in the lung, as reflected by increased numbers of HO-1+ macrophages, which is in accord with previous reports (Han et al., 2005; Risom et al., 2003). However, in contrast to the effects of loss of iNOS on radiation-induced BAL protein and cell content, expression of phospho-H2A.X, a marker of repair of double-strand DNA breaks was unaltered and HO-1+ macrophages appeared more rapidly. These data indicate that although RNS do not contribute significantly to DNA damage following radiation exposure, they play role in modulating early onset of oxidative stress in the lung.

Accumulating evidence suggests that inflammatory cells and mediators they release including TNF-α, eicosanoids, chemokines, and growth factors, are key to the initiation and perpetuation of lung injury following radiation exposure (Ao et al., 2009; Cachaco et al., 2010; Chai et al., 2013; Rube et al., 2002, 2005). TNF-α is a proinflammatory protein thought to play a dual role in radiation-induced injury, promoting inflammation immediately after exposure and later contributing to fibrosis (Johnston et al., 1996; Luo et al., 2013). Consistent with earlier studies (Rube et al., 2005), we observed increases in TNF-α in the lungs of WT mice 24 h and 4 weeks following radiation exposure. We also found that COX-2, a key enzyme mediating the generation of proinflammatory eicosanoids (Morteau, 2000), was upregulated in bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells in WT mice 4 weeks post radiation; similar upregulation of COX-2 in bronchial epithelium has been noted in mice 2 weeks post radiation exposure (Chai et al., 2013). TNF-α has been reported to regulate COX-2 expression via activation of NF-κB (Cho et al., 2013; Ke et al., 2007; Nakao et al., 2002). Further studies are needed to determine if an analogous regulatory pathway is involved in COX-2 expression in our model. Although loss of iNOS had no significant effect on TNF-α expression following radiation exposure, COX-2 protein increased, suggesting that RNS negatively regulate the production of lipid mediators during radiation-induced inflammatory responses.

Ym1 is a 45 kDa heparin-binding protein generated by antiinflammatory/profibrotic M2 macrophages (Chang et al., 2001). Exposure of WT mice to radiation was associated with increased numbers of Ym1+ macrophages in the lung, which was observed at 4 weeks. These cells were enlarged and foamy, consistent with the morphology of profibrotic M2 macrophages (Misson et al., 2004). Interestingly, in the absence of iNOS, small Ym1+ macrophages appeared in the lung within 24 h of radiation exposure; by 4 weeks, however, these cells resembled foamy profibrotic macrophages observed in WT mice. The fact that increases in small Ym1+ macrophages were observed in the lungs of iNOS−/− mice within 24 h of radiation exposure suggests early initiation of tissue repair in these animals. This is supported by our findings of persistent increases in lipocalin-2 in iNOS−/− mice, which is associated with M2 macrophage activation and the resolution of acute inflammatory responses (Warszawska et al., 2013).

Our findings that radiation exposure was associated with alterations in SP-D dodecamer structure prompted us to evaluate the contribution of SP-D to lung injury. Loss of SP-D has been reported to enhance the sensitivity of the lung to cigarette smoke, hyperoxia, ozone, and bleomycin (Aono et al., 2012; Bridges et al., 2000; Groves et al., 2012; Jain et al., 2008). Similarly, we found that SP-D−/− mice were more sensitive to radiation, as measured by greater increases in BAL protein 4 weeks post exposure, as well as increased numbers of enlarged HO-1+ macrophages in the lung 24 h and 4 weeks post exposure, when compared with WT mice. In contrast, radiation-induced expression of phospho-H2A.X, was reduced in the lungs of SP-D−/− mice, suggesting that inflammatory mediators controlled by SP-D contribute to the regulation of DNA damage repair. We also observed significantly higher levels of TNF-α, CCL2, CXCL2, and COX-2 in the lungs of SP-D−/− mice, relative to WT mice, following radiation exposure, which is consistent with the role of SP-D as a pulmonary collectin (Crouch et al., 2000; Gardai et al., 2003). Whereas TNF-α and COX-2 peaked 24 h post radiation in SP-D−/− mice, CCL2 and CXCL2 were prominent 4 weeks after exposure. These data indicate that in SP-D−/− mice, exposure to radiation induces a biphasic inflammatory response. Increased numbers of enlarged Ym1+ macrophages were also noted in the lungs of untreated SP-D−/− mice, which is in accord with previous reports of chronic lung inflammation and injury in these mice (Crouch, 2000; Groves et al., 2013). The observation that these cells were unaltered by radiation exposure, suggests that in chronically injured lungs, numbers of antiinflammatory Ym1+ macrophages are already maximally elevated.

In contrast to earlier studies (Atochina-Vasserman et al., 2007; Knudsen et al., 2014), loss of iNOS had only minor effects on the response of SP-D−/− mice to radiation, whereas significant changes were noted relative to loss of iNOS alone. Thus, radiation-induced increases in BAL protein and cell content in the lungs of iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice, as well as lipocalin-2, COX-2 and phospho-H2A.X expression, and HO-1+, and Ym1+ macrophages, were similar to or greater than in SP-D−/− mice. These findings are distinct from the effects of loss of only iNOS, which resulted in reduced levels of BAL protein and cell content, but increases in HO-1 and COX-2, with no effects on expression of phospho-H2A.X or TNF-α. It has previously been demonstrated that suppression of iNOS in SP-D−/− mice reduces irritant-induced inflammatory abnormalities and restores pulmonary function (Atochina-Vasserman et al., 2007; Knudsen et al., 2014). In this context, it is interesting to note that in our studies, although loss of iNOS had only minor effects on the sensitivity to radiation produced by loss of SP-D, it did alter inflammatory signaling. Thus, in iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice, expression of TNF-α, CCL2, and CXCL2 were close to levels observed in WT mice after radiation exposure. These findings, together with the observation that neither Ym1+ macrophages nor lipocalin-2 was significantly altered in iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice, when compared with SP-D−/− mice, suggest that there is a specific reduction in proinflammatory macrophage functioning. Taken together, these data indicate that in the absence of SP-D, RNS promote proinflammatory responses. Further studies are needed to determine if this is due to S-nitrosylation of other regulatory proteins in the lung.

Exposure of the lung to radiation results in both acute and long-term pathologic consequences. The present studies demonstrate that radiation-induced injury is associated with disruption of SP-D oligomeric dodecamer structure, oxidative stress, expression of inflammatory mediators, and profibrogenic processes in the lung. Whereas RNS derived from iNOS play a significant role in altered SP-D structure and acute lung injury, increases in the sensitivity of SP-D−/− mice to radiation are largely independent of RNS. These findings, which are summarized in Table 1, suggest that that there is a complex interplay between oxidative and nitrosative stress, as well as inflammatory pathways that mediate lung injury following exposure to radiation.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the Effects of Radiation Exposure on Markers of Lung Injury, Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in WT and Mutant Mice

| WT | iNOS−/− | SP-D−/− | iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAL protein | +a | nc | nc | ++a,b,c,e | |

| BAL cells | +a | nc | +a | +a | |

| BAL lipocalin-2 protein | nc | +a | nc | nc | |

| Lung lipocalin-2 mRNA | +a | +a | nc | nc | |

| HO-1 protein | ± | + | +++ | ++ | 24 h |

| TNF-α mRNA | +a | +a | +++a,b,c,d | nc | |

| CCL2 mRNA | nc | nc | nc | nc | |

| CXCL2 mRNA | nc | nc | nc | nc | |

| COX-2 protein Alveolar cells | nc | ++ | + | nc | |

| Bronch. epith. | nc | ++ | + | − | |

| Ym1 protein | nc | +d,e | nc | nc | |

| BAL protein | nc | nc | ++a,b,c | ++a,b,c | |

| BAL cells | nc | nc | nc | ++a,b,c,e | |

| BAL lipocalin-2 protein | nc | ++a,b | ++a,b | ++a,b | |

| Lung lipocalin-2 mRNA | +a | ++a,b | nc | nc | |

| HO-1 protein | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| TNF-α mRNA | +a | + | nc | nc | 4 weeks |

| CCL2 mRNA | nc | nc | ++a,b,c,d | nc | |

| CXCL2 mRNA | nc | nc | ++a,b,c,d | nc | |

| COX-2 protein Alveolar cells | ++ | ++ | + | − | |

| Bronch. epith. | ++ | ++ | − | − | |

| Ym1 protein | ++ | ++ | nc | nc | |

Note. nc, no change relative to untreated control; +++, high expression; ++, intermediate expression; +, low expression; ± low/no expression; −, reduced expression compared with untreated control; Bronch. epith., bronchial epithelium.

aSignificantly (P ≤ .05) different from respective untreated mice; bSignificantly (P ≤ 0.05) different from WT mice at the same post exposure time point; cSignificantly (P ≤ 0.05) different from iNOS−/− mice at the same post exposure time point; dSignificantly (P ≤ 0.05) different from iNOS−/−/SP-D−/− mice at the same post exposure time point; eSignificantly (P ≤ 0.05) different from SP-D−/− mice at the same post exposure time point.

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grants K01HL096426, R01ES004738, R01CA132624, U54AR055073 and P30ES005022.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr. Amy Pastva (Duke University, NC) for kindly providing anti-SP-D antibody DU117.

REFERENCES

- Ao X., Zhao L., Davis M. A., Lubman D. M., Lawrence T. S., Kong F. M. (2009). Radiation produces differential changes in cytokine profiles in radiation lung fibrosis sensitive and resistant mice. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aono Y., Ledford J. G., Mukherjee S., Ogawa H., Nishioka Y., Sone S., Beers M. F., Noble P. W., Wright J. R. (2012). Surfactant protein-D regulates effector cell function and fibrotic lung remodeling in response to bleomycin injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 185, 525–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atochina-Vasserman E. N. (2012). S-nitrosylation of surfactant protein D as a modulator of pulmonary inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1820, 763–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atochina-Vasserman E. N., Beers M. F., Kadire H., Tomer Y., Inch A., Scott P., Guo C. J., Gow A. J. (2007). Selective inhibition of inducible NO synthase activity in vivo reverses inflammatory abnormalities in surfactant protein D-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 179, 8090–8097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atochina-Vasserman E. N., Winkler C., Abramova H., Schaumann F., Krug N., Gow A. J., Beers M. F., Hohlfeld J. M. (2011). Segmental allergen challenge alters multimeric structure and function of surfactant protein D in humans. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 183, 856–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atochina E. N., Beers M. F., Hawgood S., Poulain F., Davis C., Fusaro T., Gow A. J. (2004). Surfactant protein-D, a mediator of innate lung immunity, alters the products of nitric oxide metabolism. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 30, 271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banath J. P., Olive P. L. (2003). Expression of phosphorylated histone H2AX as a surrogate of cell killing by drugs that create DNA double-strand breaks. Cancer Res. 63, 4347–4350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla D. K. (1999). Ozone-induced lung inflammation and mucosal barrier disruption: Toxicology, mechanisms, and implications. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 2, 31–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botas C., Poulain F., Akiyama J., Brown C., Allen L., Goerke J., Clements J., Carlson E., Gillespie A. M., Epstein C., Hawgood S. (1998). Altered surfactant homeostasis and alveolar type II cell morphology in mice lacking surfactant protein D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 95, 11869–11874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges J. P., Davis H. W., Damodarasamy M., Kuroki Y., Howles G., Hui D. Y., McCormack F. X. (2000). Pulmonary surfactant proteins A and D are potent endogenous inhibitors of lipid peroxidation and oxidative cellular injury. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 38848–38855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachaco A. S., Carvalho T., Santos A. C., Igreja C., Fragoso R., Osorio C., Ferreira M., Serpa J., Correia S., Pinto-do-O P., Dias S. (2010). TNF-α regulates the effects of irradiation in the mouse bone marrow microenvironment. PLoS ONE 5, e8980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y., Calaf G. M., Zhou H., Ghandhi S. A., Elliston C. D., Wen G., Nohmi T., Amundson S. A., Hei T. K. (2013). Radiation induced COX-2 expression and mutagenesis at non-targeted lung tissues of gpt delta transgenic mice. Br. J. Cancer 108, 91–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang N. C., Hung S. I., Hwa K. Y., Kato I., Chen J. E., Liu C. H., Chang A. C. (2001). A macrophage protein, Ym1, transiently expressed during inflammation is a novel mammalian lectin. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 17497–17506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y. J., Yi C. O., Jeon B. T., Jeong Y. Y., Kang G. M., Lee J. E., Roh G. S., Lee J. D. (2013). Curcumin attenuates radiation-induced inflammation and fibrosis in rat lungs. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 17, 267–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch E., Hartshorn K., Ofek I. (2000). Collectins and pulmonary innate immunity. Immunol. Rev. 173, 52–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch E. C. (2000). Surfactant protein-D and pulmonary host defense. Respir. Res. 1, 93–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding N. H., Li J. J., Sun L. Q. (2013). Molecular mechanisms and treatment of radiation-induced lung fibrosis. Curr. Drug Targets 14, 1347–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich A. M., Meyer H. A., Hamelmann E. (2013). The role of lipocalins in airway disease. Clin. Exp. Allergy 43, 503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J., Gordon J. R., Haston C. K. (2011). Combined CXCR1/CXCR2 antagonism decreases radiation-induced alveolitis in the mouse. Radiat. Res. 175, 657–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardai S. J., Xiao Y. Q., Dickinson M., Nick J. A., Voelker D. R., Greene K. E., Henson P. M. (2003). By binding SIRPα or calreticulin/CD91, lung collectins act as dual function surveillance molecules to suppress or enhance inflammation. Cell 115, 13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaid A., Lehnert S. M., Chehayeb B., Chehayeb D., Kaplan I., Shenouda G. (2003). Inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitrotyrosine in mice with radiation-induced lung damage. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, e67–e72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griese M., Maderlechner N., Ahrens P., Kitz R. (2002). Surfactant proteins A and D in children with pulmonary disease due to gastroesophageal reflux. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 165, 1546–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves A. M., Gow A. J., Massa C. B., Hall L., Laskin J. D., Laskin D. L. (2013). Age-related increases in ozone-induced injury and altered pulmonary mechanics in mice with progressive lung inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 305, L555–L568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves A. M., Gow A. J., Massa C. B., Laskin J. D., Laskin D. L. (2012). Prolonged injury and altered lung function after ozone inhalation in mice with chronic lung inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 47, 776–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C. J., Atochina-Vasserman E. N., Abramova E., Foley J. P., Zaman A., Crouch E., Beers M. F., Savani R. C., Gow A. J. (2008). S-nitrosylation of surfactant protein-D controls inflammatory function. PLoS Biol. 6, e266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y., Platonov A., Akhalaia M., Yun Y. S., Song J. Y. (2005). Differential effect of γ-radiation-induced heme oxygenase-1 activity in female and male C57BL/6 mice. J. Korean Med. Sci. 20, 535–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain D., Atochina-Vasserman E. N., Tomer Y., Kadire H., Beers M. F. (2008). Surfactant protein D protects against acute hyperoxic lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 178, 805–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C. J., Piedboeuf B., Rubin P., Williams J. P., Baggs R., Finkelstein J. N. (1996). Early and persistent alterations in the expression of interleukin-1 α, interleukin-1 β and tumor necrosis factor α mRNA levels in fibrosis-resistant and sensitive mice after thoracic irradiation. Radiat. Res. 145, 762–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke J., Long X., Liu Y., Zhang Y. F., Li J., Fang W., Meng Q. G. (2007). Role of NF-kB in TNF-α-induced COX-2 expression in synovial fibroblasts from human TMJ. J. Dent. Res. 86, 363–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen L., Atochina-Vasserman E. N., Guo C. J., Scott P. A., Haenni B., Beers M. F., Ochs M., Gow A. J. (2014). NOS2 is critical to the development of emphysema in Sftpd deficient mice but does not affect surfactant homeostasis. PLoS ONE 9, e85722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad F. M., Reutershan J. (2012). CXCR2 in acute lung injury. Mediators Inflamm. 2012, 740987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotecha S., Davies P. L., Clark H. W., McGreal E. P. (2013). Increased prevalence of low oligomeric state surfactant protein D with restricted lectin activity in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from preterm infants. Thorax 68, 460–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskin J. D., Heck D. E., Laskin D. L. (2010). Nitric oxide pathways in toxic responses. In General and Applied Toxicology (Ballantine B., Marrs T., Syversen T., Eds.), pp. 425–438 Wiley-Balckwell, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Wang M., Pang Z., Jiang F., Chen J., Zhang J. (2013). Locally instilled tumor necrosis factor α antisense oligonucleotide contributes to inhibition of TH 2-driven pulmonary fibrosis via induced CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J. Gene Med. 15, 441–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matalon S., Shrestha K., Kirk M., Waldheuser S., McDonald B., Smith K., Gao Z., Belaaouaj A., Crouch E. C. (2009). Modification of surfactant protein D by reactive oxygen-nitrogen intermediates is accompanied by loss of aggregating activity, in vitro and in vivo. FASEB J. 23, 1415–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medhora M., Gao F., Jacobs E. R., Moulder J. E. (2012). Radiation damage to the lung: Mitigation by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Respirology 17, 66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misson P., van den Brule S., Barbarin V., Lison D., Huaux F. (2004). Markers of macrophage differentiation in experimental silicosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 76, 926–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morteau O. (2000). Prostaglandins and inflammation: The cyclooxygenase controversy. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz) 48, 473–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movsas B., Raffin T. A., Epstein A. H., Link C. J., Jr (1997). Pulmonary radiation injury. Chest 111, 1061–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao S., Ogtata Y., Shimizu E., Yamazaki M., Furuyama S., Sugiya H. (2002). Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α)-induced prostaglandin E2 release is mediated by the activation of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) transcription via NFkB in human gingival fibroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 238, 11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki Y., Hasegawa Y., Takeuchi A., Fan Z. H., Isobe K. I., Nakashima I., Shimokata K. (1997). Nitric oxide as an inflammatory mediator of radiation pneumonitis in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 272, L651–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrofesa R. A., Turowski J. B., Arguiri E., Milovanova T. N., Solomides C. C., Thom S. R., Christofidou-Solomidou M. (2013). Oxidative lung damage resulting from repeated exposure to radiation and hyperoxia associated with space exploration. J. Pulm. Respir. Med. 3, 1000158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risom L., Moller P., Vogel U., Kristjansen P. E., Loft S. (2003). X-ray-induced oxidative stress: DNA damage and gene expression of HO-1, ERCC1 and OGG1 in mouse lung. Free Radic. Res. 37, 957–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roudkenar M. H., Halabian R., Ghasemipour Z., Roushandeh A. M., Rouhbakhsh M., Nekogoftar M., Kuwahara Y., Fukumoto M., Shokrgozar M. A. (2008). Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin acts as a protective factor against H2O2 toxicity. Arch. Med. Res. 39, 560–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roudkenar M. H., Kuwahara Y., Baba T., Roushandeh A. M., Ebishima S., Abe S., Ohkubo Y., Fukumoto M. (2007). Oxidative stress induced lipocalin 2 gene expression: Addressing its expression under the harmful conditions. J. Radiat. Res. 48, 39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rube C. E., Uthe D., Wilfert F., Ludwig D., Yang K., Konig J., Palm J., Schuck A., Willich N., Remberger K., et al. (2005). The bronchiolar epithelium as a prominent source of pro-inflammatory cytokines after lung irradiation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 61, 1482–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rube C. E., Wilfert F., Uthe D., Schmid K. W., Knoop R., Willich N., Schuck A., Rube C. (2002). Modulation of radiation-induced tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) expression in the lung tissue by pentoxifylline. Radiother. Oncol. 64, 177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo R. C., Guabiraba R., Garcia C. C., Barcelos L. S., Roffe E., Souza A. L., Amaral F. A., Cisalpino D., Cassali G. D., Doni A., et al. (2009). Role of the chemokine receptor CXCR2 in bleomycin-induced pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol 40, 410–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji C., Shioya S., Hirota Y., Fukuyama N., Kurita D., Tanigaki T., Ohta Y., Nakazawa H. (2000). Increased production of nitrotyrosine in lung tissue of rats with radiation-induced acute lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 278, L719–L725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warszawska J. M., Gawish R., Sharif O., Sigel S., Doninger B., Lakovits K., Mesteri I., Nairz M., Boon L., Spiel A., et al. (2013). Lipocalin 2 deactivates macrophages and worsens pneumococcal pneumonia outcomes. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 3363–3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M., Whitsett J. A. (2006). Alveolar macrophages and emphysema in surfactant protein-D-deficient mice. Respirology 11 (Suppl.), S37–S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]