Abstract

Purpose:

To summarize the evidence on SCI-related education literature, while looking at potential barriers, solutions, benefits, and patient preferences regarding SCI patient education.

Method:

A literature review was conducted using 5 electronic databases. Quality appraisal instruments were designed to determine the methodological rigor of the quantitative and qualitative studies found. Selected articles were read in their entirety and themes were abstracted.

Results:

Fourteen articles met the inclusion criteria for this narrative literature review, all of which were based on research studies. Seven of these 14 were quantitative studies, 3 were qualitative studies, and 4 were mixed-methods studies.

Conclusion:

To improve SCI education during rehabilitation, programs should maximize the receptiveness of newly injured patients to SCI-related information, optimize the delivery of SCI education, increase the number of opportunities for learning, promote and support lifelong learning, and include patient and program evaluation. How these strategies are specifically implemented needs to be determined by program management in consultation with various stakeholders, whilst considering the unique characteristics of the rehabilitation facility.

Keywords: adult learning, education, patient, rehabilitation, spinal cord injury (SCI)

The initial months of rehabilitation are daunting, yet paramount, for successful achievement of goals following a spinal cord injury (SCI). There has been a growing understanding and recognition of the importance of SCI-related education during rehabilitation. Patients with SCI benefit from learning how to self-advocate and to direct every aspect of their care. Knowledge about how their “new” body functions; how to predict, recognize, and respond to adverse health complications; and what physical and psychological challenges may arise are just a few examples of pertinent educational needs. For individuals who have sustained an SCI, education is required for successful health maintenance as well as improved quality of life and community reintegration.1

There are many limitations to the development of effective education programs; as time, money, and other resources become scarce, prioritization and effective planning are of the utmost importance.2 Various forms of scientific literature regarding SCI patient education exist for this purpose. The aim of this article is to synthesize and discuss the SCI-related patient education literature in the form of a narrative overview. Results are expected to provoke thoughtful consideration of potential barriers, solutions, benefits, and patient preferences regarding SCI patient education. The unique characteristics of a specific organization, along with stakeholder input and the findings from this review, should assist management and health care professionals in the planning, revision, and delivery of effective SCI educational interventions.

Methods

Search strategy

A search was initiated with the following parameters: population (patients with SCI), intervention (education), and outcome (any outcome). Five electronic databases were selected for the literature review using OvidSP databases gateway (UBC Full Text Journals@Ovid, all EBM Reviews [Cochrane DSR, ACP Journal Club, DARE, CCTR, CMR, HTA, and NHSEED], EMBASE, Health and Psychosocial Instruments, and Ovid MEDLINE) from 1946 to present with daily update. The search was limited to articles published in 1990 or later. With an advanced Ovid search, the 5 databases were screened for articles containing the following key word terms in a title search: (education OR educational OR educating OR information OR teaching OR learning OR lesson OR lessons OR knowledge) AND (spinal cord injury OR spinal cord injuries OR spinal cord-injured OR spinal cord injured OR SCI OR spinal injury OR spinal injuries OR spinal cord-disabled OR spinal injured OR spinal cord lesion OR spinal cord lesions OR spinal cord damage OR paraplegia OR tetraplegia OR quadriplegia).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Titles of the articles obtained were screened by 2 of the authors (K.v.W. and A.B.). All research studies (quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods) were considered for inclusion. Only articles that were published in English and that, from the title, were expected to address the educational needs, process, or outcomes of individuals with SCI, their family, or care providers were included. Additional articles were excluded by title when it was clear that they only addressed the education around a very specific SCI education topic. All articles meeting the inclusion criteria and published between 1990 and December 2013 were obtained in full text and read in their entirety.

All quantitative and qualitative articles were reviewed to determine their quality and relevance to the objectives of this literature review. Two quality appraisal instruments, designed for the purpose of this review, were used to determine the methodological rigor of both the quantitative and qualitative studies. Any research articles scoring less than 70% on these quality appraisal tools were not included. There were no articles that were excluded based on the quality appraisal process.

Information abstraction

The “matrix method” of conducting a literature review was employed, and thus a methodical abstraction of the information contained within the selected articles was performed.3 Themes were selected based on the purpose of the literature review and the knowledge gained from a preliminary review of the articles.

Results

Search findings

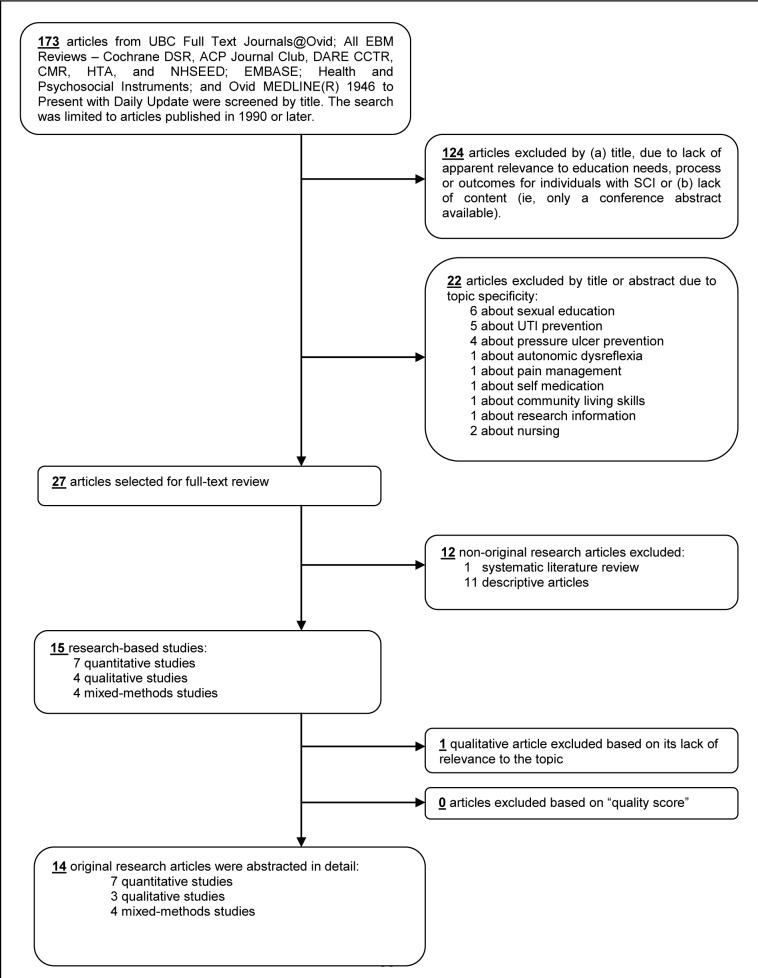

Fourteen articles met the inclusion criteria and were selected for this literature review. Figure 1 illustrates the results of the study selection process. Of the 14 articles, 7 were based on quantitative studies,2,4–9 3 were based on qualitative studies,1,10,11 and 4 were based on mixed-methods studies.12–15

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the study selection process and results. SCI = spinal cord injury; UTI = urinary tract infection.

Themes

The aims and results of the studies that were selected for this review ranged from describing challenges to SCI patient education to identifying the learning needs of those with SCI; some studies went as far as to propose, present, or develop solutions, strategies, resources, and tools to enhance SCI patient education. Upon completion of the information abstraction process, 12 main themes and 8 secondary themes (under “education delivery”) were identified (see box, “Themes Extracted from Research Pertaining to SCI Patient Education”). Information pertaining to each of these themes was extracted from the articles selected (Table 1).

Table 1. Information pertaining to various themes extracted from articles selected for this review.

| Article | Type | Themes | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Education delivery | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Barriers | 2. Adult learning theory | 3. Developing a receptive student-patient | 4. SCI topics and content | 5a. Program description | 5b. Selecting a teacher | 5c. Learning styles and teaching strategies | Group dynamics and facilitation | 5e. Environmental factors | 5f. Teaching tools | 5g. Online resources | Print resources | 6. Family involvement | 7. Peer involvement | 8. Education program evaluation | 9. Assessment of patient knowledge | 10. Documentation | 11. Implementing change – issues and strategies | 12. Direction for future research | ||

| Hart, Rintala, & Fuhrer (1996)2 | Quantitative | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||

| Gontkovsky, Russum, & Stokic (2007)4 | Quantitative | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Burkell, Wolfe, Potter, & Jutai (2006)5 | Quantitative | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| May, Day, & Warren (2006)6 | Quantitative | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Theitje et al (2011)7 | Quantitative | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||

| Matter et al (2009)9 | Quantitative | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Edwards, Krassioukov, & Fehlings (2002)8 | Quantitative | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||

| May, Day, & Warren (2006)10 | Qualitative | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Olinzock (2004)1 | Qualitative | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||

| Lucke (1997)11 | Qualitative | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||

| Shepherd et al (2012)13 | Mixed methods | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Schladen et al (2011)14 | Mixed methods | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Hoffman et al (2011)15 | Mixed methods | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||

| Payne (1993)12 | Mixed methods | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

Discussion

Barriers to SCI patient education

Barriers to SCI education emerged as a particularly strong theme in the literature; 5 specific challenges were consistently identified.

A lack of available quality information sources. There is a lack of access to patientpreferred information sources (ie, health care professionals)4,5,7,9,13 and a lack of existing quality in the sources of information that are easily accessed (ie, Internet Web sites).5,7–9 Transportation, geographic, economic, physical, time, and organizational constraints were identified as challenges to accessing information.4,5,12,14,15

Difficulty facilitating learning readiness. The various physical and psychological stressors experienced by individuals in the acute phase following an SCI are recognizable barriers to their optimal presence and participation in educational opportunities.1,10,13,15 Authors reported on the importance of demonstrating relevance of information during the period of acute rehabilitation, especially when patients have not yet experienced the complications they are expected to learn how to avoid and manage.5 It is understandably challenging for patients to perceive the importance of information, which will prove necessary in the future, when they are dealing with more immediate physical and psychological stresses.

The vast amount of information that should be learned in a short amount of time. Shorter rehabilitation stays, accompanied by factors such as decreased access to SCI specialists after discharge, have created a situation in which patients and families must acquire information and learn as much as they can during their time in rehabilitation settings.1,2,7,9,11,13,15

The various health care and societal changes that have created or exacerbated organizational challenges. These changes include decreased lengths of stay, shortages of nursing personnel, increased patient to nurse ratios, increased trends toward 2-income families, and increased expectations (from patients and families) for information and control over health decisions.1,2,6,7,9–11,13,15 These changes have exacerbated scheduling issues, workload management challenges, resource scarcity, family stresses, and fragmented education programs.6,10,13

Themes Extracted from Research Pertaining to SCI Patient Education

Barriers and/or challenges to learning and/or teaching

Adult learning theory

Developing a receptive student-patient

Topics and content

- Education delivery

- Program descriptions

- Selecting a teacher

- Learning styles and teaching strategies

- Group dynamics and facilitation

- Environmental factors

- Teaching tools

- Online resources

- Print resources

Family involvement

Peer involvement

Education program evaluation

Assessment of patient knowledge

Documentation

Implementing change – issues and strategies

Direction for future research

The physical and psychological impacts experienced by individuals with SCI in rehabilitation have been termed “learning affect” by May and colleagues.10 Fatigue from medications, pain, and an intense physical rehabilitation schedule, compounded by emotional turmoil, may decrease a patient’s progression through the stages of readiness to learn.1,13,15 This is unfortunate timing considering that “SCI rehabilitation may be the best opportunity from a resource perspective to deliver patient education yet the significant challenges associated with the physical and psychological effects of the injury may impact learning readiness.”10(p1047) Compound this with health care changes that result in decreased lengths of stay in inpatient rehabilitation7,9,13 and the sheer volume of the information that should be taught8,15 and it becomes clear that patients are likely to be discharged before all their information needs are met.

This is occurring at a time when it is even more crucial than ever that persons living with SCI in the community are able to direct their own care. With increased survival rates and an evergrowing number of individuals with SCI striving to live independently in their communities, care providers who are knowledgeable about SCI-related health complications are in high demand, yet scarce.5,7,9 There is a real need for community-based patient education programs; however, the barriers to accessing quality information sources are the greatest in the community.4,5

It is this combination of barriers to information that enhances the need for thoughtful SCI patient education programming, and it could be the reason that SCI patient education has attracted significant attention in the past 2 decades. Identifying existing obstacles is an important step in facilitating change. After presenting factors that hinder SCI patient education, each article reviewed for this narrative overview also presented strategies for improving SCI patient education.

Adult learning theory

Adult learning principles, and how they are, or are not, being applied in the rehabilitation learning process, are pertinent to the discussion of SCI education. Knowles16 can be credited with pioneering the work in adult learning theory; he concluded that there are several distinct characteristics of adult learners that differ from child learners (see box, “Several Unique Characteristics of Adult Learners”16–18). Educators within the health care field must take a unique approach when teaching adult patients. As Russel17(p349) states,

For the teaching to be as effective as possible, knowledge about adult-learning principles is essential. Understanding why and how adults learn and incorporating the learner’s preferred learning style will assist the health care provider in attaining the goals set for each patient and increase the chances of teaching success.

Barrier 2 identified above – difficulties facilitating learning readiness – relates to the adult education principles addressing relevance and motivation to learn.10,13,17,18 The inability of some SCI patients to recognize the necessity of SCI education may point to the fact that health care professionals are not routinely utilizing the principles of adult education or are not portraying the information in a manner that is accessible and acceptable to the adult SCI patient. This would be understandable considering that health care professionals often receive inadequate training on how to be patient educators.19 On the other hand, perhaps the expectations for the team (including health care professionals, patients, and their families) is too high. The expectation to deliver or receive education on a daily basis, when patients and family members are not in an appropriate state in which to learn, could be unreasonable.

Several Unique Characteristics of Adult Learners16–18

Adults are able to work independently and self-direct much of their learning.

Adults have a wealth of experiences and knowledge that contribute to their learning.

Adult learning must be oriented around and relevant to their life goals and circumstances.

Adult learners must have an inner motivation to learn something.

Adult learners need to be treated respectfully.

Regardless, the literature strongly supports the incorporation of principles of adult learning theory into SCI patient education programming.1,2,6,10,12,13 Perceived benefits of doing so include improved effectiveness of SCI patient education programming,6,10,13 improved patient skills in the application of knowledge,6 and enhanced ownership and responsibility for health and actions.6

Health care professionals need to make information about patients’ injuries, illnesses, and risks for complications relevant and meaningful. Health care professionals should receive training regarding adult education and should be enabled to use the principles of adult education in their interactions with patients.

Core requisites for successful patient education programming

The themes and barriers found in the literature search were used to identify 5 core requisites for successful SCI patient education programming. These requisites are as follows:

Maximizing the receptiveness of patients to SCI-related information

Optimizing the delivery of SCI education

Increasing the number of opportunities for learning

Promoting and supporting ongoing SCI education

Incorporating program and patient evaluation

Maximizing the receptiveness of patients to SCI-related information

The importance of education as a component of a patient’s rehabilitation must be emphasized.10 Strategic planning, together with a commitment from each member of the interdisciplinary team, may help to ensure that this message is communicated on an ongoing basis.

Limiting the impact of barriers to readiness to learn is another important strategy.1 Physical and psychological distracters need to be diminished,1,4,11 the patient needs to adjust to his or her injury,4,11 and the adult learner needs to develop a perceived need for the information.6 An individualized rehabilitation approach is particularly effective in helping to eliminate these barriers, particularly if patients are engaged in the planning process, such as in goal setting and decision making surrounding their care and education.8,11 Adult patients need to be given autonomy and become empowered in their self-directed learning in order for their SCI education to be effective.11,13

The passage of time and physical healing cannot be overlooked when discussing the receptiveness of patients to SCI information. Data suggest that, as time passes after injury, a patient’s physical and mental health improves,8 thus supporting the notion that education is better received once more time has elapsed since onset of injury. This supports a recommendation for the provision of SCI patient education in the community setting, but it should not diminish the commitment to provide quality education during acute rehabilitation.

Much of the research recognizes the importance of selecting the right content or topics for SCI education programs at various stages of reintegration after SCI.2,4,6,8–10,12,13,15 Topics that are taught in order of the hierarchy of perceived need should be better received by the majority of patients.6 For persons with newly sustained SCI, topics of perceived importance consistently include those relating to the function of the spinal cord and the effects of SCI, as well as individual health management (such as bladder, bowel, and skin care and autonomic dysreflexia).6,9,10 Greater access to information regarding SCI research and trials has also been identified as being important to SCI patients.8 A limitation to classroom or seminar-structure education programs is that it is difficult to arrange the order of topics ideally for each patient. Usually these classes are presented in a rotation and patients either join in at any point during the rotation or lose out on an opportunity to learn whilst awaiting the start of the next rotation. Online modules and videos are thus beneficial in providing patients with quality information at the time of need.13–15

Optimizing the delivery of SCI education

Most of the articles selected provide strategies for optimizing the delivery of SCI education, including family involvement, peer involvement, problem-based learning, multiple methods of teaching, and educator selection and development.

Family involvement. It was reported by patients participating in the study by May and colleagues10 that family involvement, within group learning, was beneficial to the SCI education process. A study on SCI information sources points out that patients view family members as an important source of information.5 It makes sense to educate family and direct them to appropriate resources. Involving the family in education efforts is particularly important when family members plan to provide personal care10 or when the person with SCI is not progressing through the readiness to learn phases.5 Family education is also key to maintaining good interpersonal relationships after SCI.12

Peer involvement. There is a clear and strong recommendation for peer involvement as a way to improve education delivery and uptake.4–6,10,12,13 A certain degree of peer support is already inherent in most SCI rehabilitation facilities. However, benefits are expected from increasing the amount of formal peer input and participation. Peer involvement provides a forum for group discussion, problem solving, consultation activities, and sharing of experiences, concerns, and support.10 Various benefits accredited to this include facilitation of knowledge acquisition, enhanced awareness of information needs, and motivation and emotional support from peers.6,10,12 Exposure to new information and experiences in the presence of others with SCI during the rehabilitation phase can also assist patients in adjusting to their injuries.4,10,11 Peer involvement has been determined to be beneficial in both in-person and online learning (ie, through the use of video testimonials and peers demonstrating skills via online videos).13–15 The partnered efforts of rehabilitation professionals and individuals living with SCI in the development of online and print educational materials is believed to enhance the credibility of the resources.13,15

It is important to recognize the limitations and conditions around peer involvement. Not all SCI education topics are conducive to being taught, or explored, in a group setting. It is equally important for health care professionals to address the individual needs of patients on a one-on-one basis.10 Similarly, educators taking advantage of group learning should be aware of the diverse individual characteristics that will be inherent in an SCI patient group, such as socioeconomic background, level of injury, age, and gender. The benefits of group learning are also diminished when one person dominates the conversation or steers the conversation off topic.10 Group facilitators should be aware of group dynamics and guide the conversation in order to avoid such occurrences.

Problem-based learning. Problem-based learning is an adult learning strategy that has gained popularity over the past few years. Many articles have recommended the inclusion of problem solving, case studies, group discussions, and other problem-based teaching strategies to optimize SCI education delivery.6,10–12 Problem-based learning is expected to promote knowledge application skills in a way that pure information delivery or information recall exercises does not.6

Multiple methods of teaching. Individuals learn best when different strategies are employed; accordingly there is a strong recommendation to consider multiple methods of teaching when planning education programs.6,10,13 Shepherd and colleagues,13(p320) who advocate for the use of online education resources, state that

the use of multiple methods in structured format has been shown to enhance the effectiveness of patient education. For the purposes of SCI rehabilitation, a blended model of instruction is the best option, combining e-learning and other resources with in-person instruction.

Many of the articles recommend that the preferred learning styles of each patient be determined, so that education delivery methods can be matched to each patient appropriately.1,10,13 The teaching style to which patients are likely to respond best is related to their stage of readiness to learn, thus it is recommended that educators monitor the readiness to learn of each patient and adjust the teaching approach accordingly.1,13

Educator selection and development. Health care professionals, especially SCI specialists, are viewed as the most reliable and preferred source of medical information related to SCI.4,5,9 May and colleagues10 found that clinicians who have pre-existing and positive relationships with the patients (ie, the on-site physiotherapists, occupational therapists, etc) are best suited to provide SCI education. Ideally, educators should remain flexible and observant, display confidence, and adjust their teaching approach based on the verbal and nonverbal feedback and reactions from patients.1,10 As was mentioned earlier, May and colleagues also recommend that health care professionals obtain training in patient education, preferably including adult education principles, so that they can most effectively relay information when working with adult patients with SCI.

Increasing the number of opportunities for learning

Once patients and their families are ready and willing to receive information, learning opportunities need to be expanded beyond formal education sessions. Accessibility and quality are the 2 characteristics of information sources that are most prized by patients.5 One possible source of accessible high-quality educational materials is mass media.13–15

Burkell5(p261) determined that “most people (88%) reported using multiple sources [of information], with a medium of four different information sources per individual.” SCI education programs should incorporate numerous resources such as the Internet, computer-based multimedia programs, videos, other information and communication technologies (ICT), medical books, patient manuals, printed reading materials, educational games, and so on.4–7,9,10,13,15

The Internet and computer-based multimedia programs are resources that have gained popularity in the past few years.4–10,13–15 The use of e-learning has been found to be beneficial in many ways, including creating more engaging learning experiences, increasing accessibility of educational information, providing up-to-date and current information, and reducing costs of teaching.13–15 Video media in particular increase understanding and retention of knowledge when compared to written or in-person information.15 A study by Edwards and colleagues8 found that the majority of persons living with SCI in the community reported being very comfortable with using the Internet and that it was their preferred tool for accessing SCI-related information. The article by Shepherd and colleagues13 echoed this sentiment.

Nonetheless, a few articles selected for review present a cautionary note on the use of the Internet and other ICT. Although the Internet is a great educational tool, disparities exist with regard to access and degree of understanding of material presented online, based on factors such as ethnicity and educational background.9,14 Having a variety of Internet-based learning platforms, including media that require no more than a basic reading level, such as YouTube videos, helps to address some of these disparities.14 Regardless, as Matter and colleagues9(p552) state, “it continues to be necessary to distribute information in a variety of formats and not rely exclusively on Web-based dissemination.”

Interpersonal educational encounters should also be increased where possible. Formal teaching sessions should be frequent6 and patient attendance at these sessions should be expected. Interpersonal resources can be made more available to persons with SCI living in the community, or more rural areas, by utilizing community organizations as well as ICT.6 In addition, staff should be encouraged and supported to take advantage of teachable moments that present themselves during day-to-day interactions with patients.11 Many health care professionals perceive that they lack the time needed for patient education20; this begs the question of whether this issue is a reflection of our priorities in health care, beliefs about education, resource allocation problems, and so on.19,20 Regardless, education is a vital component of SCI rehabilitation, and an environment where it is valued as such should be fostered.

Promoting and supporting ongoing SCI education

Inpatient education programs play an important role in promoting and supporting ongoing SCI education.7 Individuals with SCI are more likely to grow as life-long learners if the seed of ongoing education is planted when they have newly sustained injuries. It is important that inpatients become familiar with educational resources and tools they can continue to access in their home environments or communities. An inpatient who normally lives in a rural area may well benefit emotionally from seeing his or her family via videoconference; however, this benefit might be further realized when the patient is later able to conference into an educational session after being discharged home. Similarly, a patient who is guided through a process to identify useful Internet sources, or who is actively involved in developing a personal resource manual, is likely to return to these information sources once living in the community.

Inpatient SCI education programs should also encourage and support outpatient and community groups to run education programs in the community. This support could include maintaining a collaborative relationship with community organizations, providing resources to support these programs, encouraging patients to seek a teaching role to assist others in the future, or initiating the creation of these programs. In addition, formal inpatient education sessions can include outpatients or individuals living with SCI in the community.

Many of the strategies discussed in the previous 3 core requisites also promote and support ongoing SCI education. The identification of numerous information sources and the utilization of existing communication technologies encourage future use and, accordingly, future learning. If education is presented as an important component of SCI rehabilitation, it will most likely continue to be valued by the SCI community at large. In addition, many of the strategies for optimizing the delivery of SCI education can be incorporated into an outpatient education program, such as involving peers and family and strategically selecting teaching strategies and learning environments.

Incorporating program and patient evaluation into the SCI education program

Numerous authors agree that the evaluation of education programs is beneficial.4,6,10,14,15 Evaluation helps to determine the impact that the service has on patient care and outcomes.6 Various outcome measures have been identified or used by authors writing about SCI patient education. Some are specific to the SCI population (eg, the Spinal Cord Independence Measure – Version II [SCIM II]7 and the Rehabilitation Learning Readiness Model [RLRM] for SCI1), whilst others are more general (eg, the Social Problem Solving Inventory Revised [PSI-R]21). These scales have been or could be used in SCI patient education program evaluations.

It is also beneficial to assess which information sources patients prefer or choose to utilize in the community.8 May and colleagues10 highlight the importance of tracking access to, use of, and perceived quality of various educational resources after discharge. This can help determine whether there is a relationship between the information sources to which patients are exposed as part of an education program and the sources they reference to further their knowledge after they are discharged.

If formal assessment is not a realistic option, authors have identified informal signs that indicate whether patients have increased knowledge concerning SCI, including demonstrated confidence in participating in decision making regarding their care11 and self-reports of effective problem-solving skills.6 Regardless of the method of assessment, the information extracted from a thorough program evaluation can be useful for directing program improvement efforts or when requesting additional resources for SCI educational programs.

Implementing change

The task of implementing or improving an SCI patient education program is challenging, even knowing the 5 core requisites for successful SCI education programming. Authors who have written about SCI education stress the need to consider practical issues.6 SCI program managers and education programmers should be aware of available resources as well as program strengths and limitations.6 One key resource that could be developed is an interdisciplinary SCI patient education committee; this group can explore ways in which an organization could implement various strategies. Other valuable resources that should be embraced and consulted are any interested community groups, as well as persons living with SCI.13

The need to educate staff regarding program changes and philosophies is an important practical issue.10 Staff benefit from being made aware of all changes related to their organization’s SCI education program, the principles behind the changes, and how the changes will be implemented. Implementation of an envisioned plan will be more successful if commitment is elicited from all staff from the inception of the program. This could be accomplished by providing education for staff and ensuring that task assignments are clear and appropriate and that staff members are familiar with their roles and responsibilities related to patient education.6 If interested community groups are to be formally involved in educational endeavors, then clear role assignment and sufficient education would also be valuable for them. Overall, each rehabilitation center will have its unique characteristics that will lead to differing methods for incorporating the recommendations outlined in this article.

Limitations of this review

It is important to acknowledge the limitations in this review. We completed a narrative review. Although such reviews are useful in summarizing the existing literature on a certain topic, they have a tendency to be more subjective and less objective when compared to systematic reviews, hence there is a resulting risk of bias in the evidence presented.22 Additionally, this review did not delve into specific educational topics related to SCI, such as pressure sore education, so there is a possibility that relevant and informative articles could have been overlooked.

Conclusion

It is evident from the literature that patient education is a principle component of an effective SCI rehabilitation program, but there are many potential barriers to SCI education. In light of these conflicting truths, authors have presented various strategies to minimize barriers and optimize education programming.

After thorough dissection of the themes identified from the literature, 5 key requisites emerged for a successful SCI education program. It is hoped that each organization that wants to incorporate an SCI patient education program will develop, implement, and assess strategies to address one or more of the requisites. Likewise, the hypothesis that effective SCI rehabilitation will result when various strategies are strategically implemented into the education program needs to be scientifically proven. A series of program evaluations need to be completed prior to, and following, educational program revisions. It is important that such published studies include full and clear descriptions of the initial program and the “improved” program. These program evaluation studies could be additionally beneficial if they incorporate long-term outcome measures, as well as economical data and considerations.

The results of this narrative literature review should assist in the revision or implementation of an effective SCI education program. This research could also be used to form the foundation of a proposal for the purpose of securing resources necessary to enhance an education program. Literature identified for the purpose of this review includes quality studies; therefore, until further research is completed, SCI program managers should feel confident that decisions to implement any of the strategies outlined in this literature review are based on current evidence.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Karen Anzai, Rehabilitation Consultant, SCI Program, GF Strong Rehabilitation Centre, and the GF Strong SCI Program Client and Family Education Committee are acknowledged for assisting in identifying the need for this study, for their support, and for their ongoing efforts to optimize SCI patient education.

References

- 1.Olinzock BJ.A model for assessing learning readiness for self-direction of care in individuals with spinal cord injuries: A qualitative study. SCI Nurs. 2004;21(2):69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart KA, Rintala DH, Fuhrer MJ.Educational interests of individuals with spinal cord injury living in the community: Medical, sexuality, and wellness topics. Rehabil Nurs. 1996;21(2):82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerrard J.Health Sciences Literature Review Made Easy: The Matrix Method. 2nd ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Inc; 2007:47. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gontkovsky ST, Russum P, Stokic DS.Perceived information needs of community-dwelling persons with chronic spinal cord injury: Findings of a survey and impact of race. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(16):1305–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burkell JA, Wolfe DL, Potter PJ, Jutai JW.Information needs and information sources of individuals living with spinal cord injury. Health Info Libr J. 2006;23(4):257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.May L, Day R, Warren S.Evaluation of patient education in spinal cord injury rehabilitation: Knowledge, problem-solving and perceived importance. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(7):405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thietje R, Giese R, Pouw M, et al. How does knowledge about spinal injury-related complications develop in subjects with spinal cord injury? A descriptive analysis in 214 patients. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards L, Krassioukov A, Fehlings M.Importance of access to research information among individuals with spinal cord injury: Results of an evidenced-based questionnaire. Spinal Cord. 2002;40:529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matter B, Feinberg M, Schomer K, Harniss M, Brown P, Johnson K.Information needs of people with spinal cord injuries. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32(5):545–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.May L, Day R, Warren S.Perceptions of patient education in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(17):1041–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucke KT.Knowledge acquisition and decision-making: Spinal cord injured individuals perceptions of caring during rehabilitation. SCI Nurs. 1997;14(3):87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payne JA.The contribution of group learning to the rehabilitation of spinal cord injured adults. Rehabil Nurs. 1993;18(6):375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shepherd J, Badger-Brown K, Legassic M, Walia S, Wolf D.SCI-U: E-learning for patient education in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. J Spinal Cord Med. 2012;35(5):319–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schladen M, Libin A, Ljungberg I, Tsai B, Groah S.Toward literacy-neutral spinal cord injury information and training. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2011;16(3):70–83. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffman J, Salzman C, Garbaccio C, Burns S, Crane D, Bombardier C.Use of an-demand video to provide patient education on spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34(4):404–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knowles M.The Modern Practice of Adult Education: Andragogy Versus Pedagogy. New York: Association Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russel S.An overview of adult-learning processes. Urol Nurs. 2006;26(5):349–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merriam S.Andragogy and self-directed learning: Pillars of adult learning theory. New Dir Adult Cont Educ. 2001;89:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Close A.Patient education: A literature review. J Adv Nurs. 1988;13:203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park M.Nurses’ perception of performance and responsibility of patient education. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2005;35(8):1514–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelis A, Stefan A, Colin D, et al. Therapeutic education in persons with spinal cord injury: A review of the literature. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2011;54(189):210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A.Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med. 2006;5(3):101–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]