Abstract

Objectives

We identify recent models for programs aiming to increase effective family support for chronic illness management and self-care among adult patients without significant physical or cognitive disabilities. We then summarize evidence regarding the efficacy for each model identified.

Methods

Structured review of studies published in medical and psychology databases from 1990 to the present, reference review, general Web searches, and conversations with family intervention experts. Review was limited to studies on conditions that require ongoing self-management, such as diabetes, chronic heart disease, and rheumatologic disease.

Results

Programs with three separate foci were identified: 1) Programs that guide family members in setting goals for supporting patient self-care behaviors have led to improved implementation of family support roles, but have mixed success improving patient outcomes. 2) Programs that train family in supportive communication techniques, such as prompting patient coping techniques or use of autonomy supportive statements, have successfully improved patient symptom management and health behaviors. 3) Programs that give families tools and infrastructure to assist in monitoring clinical symptoms and medications are being conducted, with no evidence to date on their impact on patient outcomes.

Discussion

The next generation of programs to improve family support for chronic disease management incorporate a variety of strategies. Future research can define optimal clinical situations for family support programs, the most effective combinations of support strategies, and how best to integrate family support programs into comprehensive models of chronic disease care.

Keywords: chronic illness, family relationships, social support, self-management, interventions

Introduction

Managing chronic illness is demanding for patients and health care providers alike. On a day to day basis, patients with illnesses such as diabetes, heart disease, and asthma are advised to take medications on complex schedules, maintain special diets, be physically active, perform regular self-monitoring, and respond to changes in their symptoms and test results. After each health care provider visit (typically every three or four months), patients often grapple with revised self-care instructions, changes in their medication regimens, referrals for medical testing, and new self-management goals. Given the complexity of these tasks, many patients need support between medical visits in order to manage their illness successfully.

While professional support services, such as nurse visits or disease education programs provide invaluable support for some patients with chronic diseases,(1, 2) these services are often poorly funded or unavailable in community practices. Even when they are in place, professional support services are often unable to provide the frequency and duration of patient follow-up necessary to truly understand patients’ needs and provide the behavior change assistance required to significantly impact quality of life and outcomes.(3, 4)

As a result of the growing gap between the need for self-care support and existing resources, family members are increasingly recognized as important allies in the care of chronically ill patients, and the last decade has seen a rapid growth of self-management programs that include family members. Recent quantitative and qualitative research has informed the development of new family interventions based on behavioral theory, which are in varying stages of evaluation.

We reviewed quantitative and qualitative studies published in the medical and psychological literature, searched publicly available family intervention protocols and curricula, and held conversations with experts in the fields of social support and family involvement in chronic illness care to identify emerging models for interventions that increase family involvement in chronic illness care. Our specific goals were to:

Summarize recent evidence on the potential effectiveness of family members as supporters for chronic illness care

Describe evidence that may explain why some family intervention models have been ineffective for adults with chronic illness

Group newer family interventions according to behavioral or chronic care theory, to develop an organizational scheme for understanding promising new directions in family interventions

Highlight research gaps and outline a research agenda for the development of effective family intervention models, based on the identified emerging research and program trends

Information for this review was collected from three sources: a structured review of published studies in on-line medical and psychological databases (described below), a review of materials from existing programs for family support identified through research databases and general Web searches, and discussions with experts in research on family support for self-management. Some of the information in this review is based on a report presented to the The California Health Care Foundation: Sharing the Care: The Role of Family in Chronic Illness.(5) That report contains in-depth logistical information that can support program implementation, such as curriculum content and informational resources for patients and family members.

The Case for Involving Family in Self-Management Support

Family members of chronically ill patients may be particularly well suited to provide sustained and effective self-management support. (In this paper we refer to ‘families’ and ‘family members’ broadly, using the Institute for Family Centered Care definition of "family" as two or more persons who are related in any way—biologically, legally, or emotionally.)(6) Family members are often an integral component of the daily context for self-care.(7, 8) Family members often strongly influence the foods brought into the patient’s household and prepared for meals. Family also can influence whether patients have time for physical activity among other competing time demands, and influence where health fits in the hierarchy of family priorities. Additionally, family members often provide important emotional support to patients facing the stresses of caring for their illness. In sum, families often create the practical, social, and emotional context for self-care, making it easier or harder for patients to achieve their health and behavior goals. As a consequence, actively engaging family members may change this self-management environment in ways that facilitate patient success.

In addition to shaping the environment in which self-care takes place, family members frequently play an active role in managing the patient’s chronic illness. Over 50 percent of people with diabetes or heart failure report that their family is involved with planning their diet and taking medications.(9–11) Family members are often the first to notice new symptoms, and most emerging health problems are handled by patients and family members without consulting a health care professional.(12) When chronically ill patients do visit a health care provider, between 30 and 50 percent are accompanied by family.(13, 14)

Family members also share many of the characteristics of successful clinician disease managers and community health workers. For example, relationships between family members and chronically-ill patients are typically long-standing and often involve frequent contact. Family members usually share the patients’ cultural background and have a detailed knowledge of the factors that influence the patient’s self-care day-to-day. Many family members have established relationships with the patient’s health care provider, either because they accompany the patient to visits or because they are a patient of that provider themselves. Contact and familiarity with the patient’s clinician has been associated with successful professional disease management;(3) for family it could lead to more opportunities to be involved in the patient’s clinical care and increased trust in their involvement by the patient or provider.

Finally, observational studies suggest that patients have better disease management and outcomes when they have increased support from family. For example, social support is associated with better glycemic control for people with diabetes, better blood pressure control for people with hypertension, fewer cardiac events for people with heart disease, and better joint function and less inflammation for people with arthritis.(15–18) These improved outcomes can be partially explained by better self-management behavior, increased illness management self-efficacy and decreased patient depressive symptoms among patients with higher levels of social support. (19–22) Social support from family may even affect patients’ health directly through lower stress hormone levels and less variation in blood pressure.(23)

Why new models are needed for promoting family involvement in chronic illness care

Health professionals have long included interested family members in clinic visits, and family sometimes participate in traditional patient education programs. However, merely including family members in patient-oriented disease education sessions has shown little impact on patient outcomes.(24) Just as patient self-management interventions are more successful when they focus on the patient’s role in illness care and are based on behavioral theory(25), new models for family involvement in illness management should also focus on the unique roles of family members and be based on sound theoretical models for interpersonal behavior and social support.

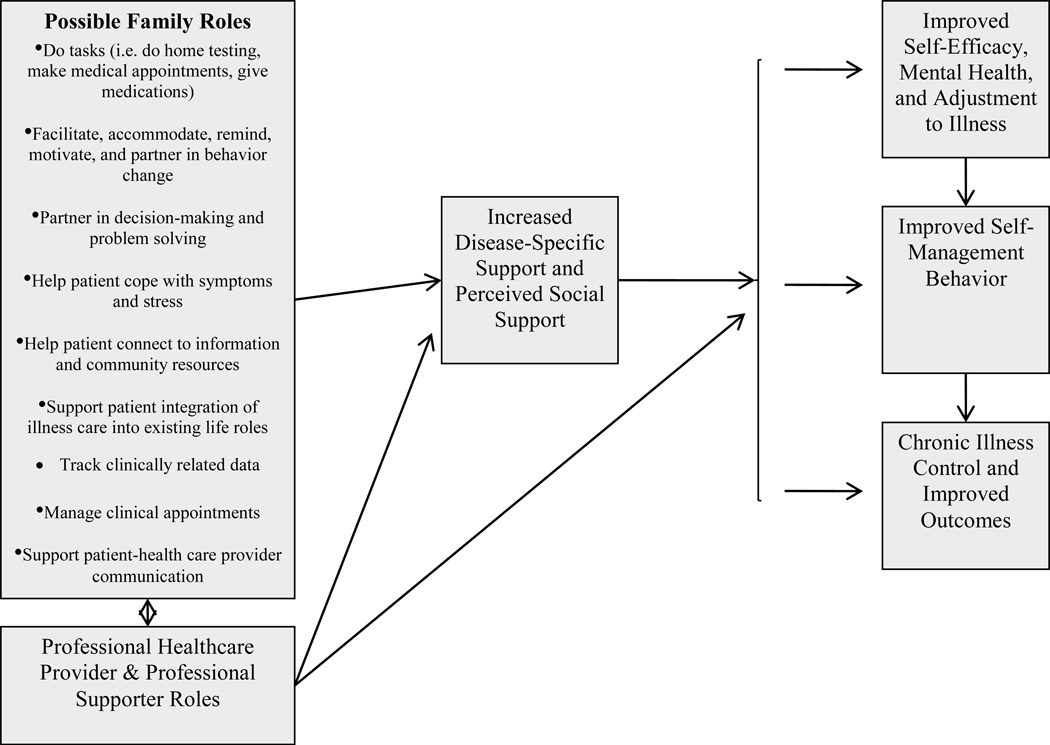

Interventions for caregivers of people with significant disabilities (e.g., patients with dementia or terminal cancer) often focus on managing caregiver stress or on teaching family members how to directly manage tasks such giving medications, helping with activities of daily living, and communicating with clinical providers as the patients’ proxy. (26–28) These interventions often are inappropriate for families seeking to support self-management of more functionally independent patients (e.g., with diabetes or asthma). As the incidence of chronic illnesses such as diabetes or hypertension is steadily increases among younger adults with few functional limitations,(29) new family support models will also need to address this group’s needs. Studies show that among adolescents with chronic illness,(30) successful family support often takes the form of facilitating self-care and providing emotional support. Similarly, family roles that are likely to be more common in supporting functionally independent adults include: facilitating and motivating patient behavior change; partnering in information gathering, assisting problem-solving and decision-making; helping patients maintain their work and social roles; and supporting the patient-health care provider relationship. Examples of these unique roles and their potential mechanisms of effect on patient outcomes are presented in Figure 1. The next generation of family support interventions should further articulate specific ways in which family members can support younger, more functionally able patients and test the mechanisms through which these approaches impact patient outcomes.

Figure 1.

Possible Family Roles in Care of Functionally Independent Adults with Chronic Illness, and Theoretical Mechanisms of Effect on Chronic Illness Outcomes

Family members of functionally independent patients also face unique pitfalls when becoming more actively involved in chronic disease management. Because patients often want to be as independent as possible in their disease self-management, family members may inadvertently overstep boundaries or offer unwanted help.(31, 32) Family members may be perceived as nagging or criticizing when trying to help,(8) or may even cause patients to be less confident in their ability to care for their own disease.(33) Thus new models for family support interventions need to remain responsive to patient preferences, involving family members in ways that support healthy family relationships, patient autonomy, and patient confidence.

Three Emerging Models

Intervention studies published between 1991 and 2008 were identified through searches of medical (Medline and CINAHL) databases, psychology (PsychInfo and Sociofile) databases, and a manual review of relevant article references. We limited our searches to illnesses that require ongoing and significant patient self-management among patients who are usually functionally independent, i.e., patients with diabetes, rheumatologic disease, hypertension and chronic heart disease, and chronic lung disease. We excluded studies exclusively focused on patients with chronic pain, mental health disorders, or patients with dementia, because patient needs and family roles differ significantly for these conditions from the target conditions. We identified 11 articles representing 9 trials of interventions aiming to change specific family roles or behaviors supporting adults with chronic illness.(33–43) Eight trials took place in the United States and one in the Netherlands. All trials were randomized, with control group patients receiving similar interventions without family members. We excluded studies of interventions that included family in patient-directed disease education only. We did not exclude studies based on the number of participants. From conversations with trial researchers and additional web searches, we also identified protocols for three new trials (44–46) and two adaptations of previously developed interventional trials (47, 48) that are currently underway (all U.S. based). All interventions identified were grouped by the family skill or behavior theory addressed. These groupings were then refined through conversations with family support researchers and family intervention developers. Here we discuss the three models that formed the basis for each completed and ongoing family intervention study identified (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of Three Emerging Models for Programs to Increase Family Support for Patients with Chronic Illness

| Family Members Set Patient Support Goals |

Family Training in Supportive Communication Techniques Two Subtypes |

Clinical Care Support Roles for Family |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral or Illness Care Theory | goal-achievement theory, motivational interviewing | coping theory | autonomy support | draws on the Chronic Care Model of integrated care support |

| Most Appropriate Setting | behavior change, especially for behaviors that affect the whole family | ongoing symptoms or activity limitations | change and maintenance of healthy behaviors | during provider visits, between-visit clinical monitoring and care coordination |

| Example | Patients in a self-management course set goals for behavior change during each week of the course. A participating family member selects a weekly concrete action that will help the patient achieve his or her goals. | Family members practice prompting or suggesting symptom adaptation techniques | Family members practice motivating and responding to patients facing challenging self-management situations without use of control or criticism | A family member is trained in the proper technique for measuring blood pressure. He or she maintains a blood pressure log to bring to the patient’s provider during visits and advises the patient to call the provider if blood pressure rises above specific parameters. |

| Advantages | Concrete goals make family roles clear | Skills can be used in changing situations over time | Potential to enhance the reach of and reduce inefficiencies in clinical care, potential to detect clinical changes earlier | |

| Disadvantages | Goal setting may not continue, Goal set for a specific situation may not help family increase support in other care domains | Applies to limited patient situations, not ideal for supporting healthy behavior maintenance | May be difficult or ineffective in families with underlying strained relationships. | Potential for interference with patient-provider relationship, increased clinician burden. |

| Strength of evidence | Mixed results for patients with rheumatologic disease, not evaluated in trials addressing other chronic illnesses | Less pain and improved physical function in two arthritis studies, equivocal findings in a third | Improved dietary adherence among heart failure patients in one study | One pilot intervention to date, although observational evidence supports the benefits of family-centered clinical care. |

| Randomized controlled trials/pilot interventions underway | Hyperlipidemia, Diabetes | Two heart failure trials | Heart failure, Diabetes | |

Family Members Set Specific Goals for Increasing Patient Support

Definition and Rationale

Families often want to be involved in patient care but do not know what support roles would be most useful or what specific actions they can take on a day to day basis. In programs based on family goal-setting, family members learn how to choose specific support roles and set concrete goals for enacting new supportive behaviors. For example, if a patient is trying to remember to take a meal-time dose of medication, their family member might choose a facilitative role, and set a goal of putting the medication bottles out when setting the table for lunch. Thus goals can define for family members “what they can do” (putting the medication bottle on the table) and also define what family members are not responsible for (whether the patient takes the medication).

Goal-setting can be guided by evidence from goal achievement research demonstrating that short-term, specific goals are more likely to be carried out.(49) Specific goals for family members could be, “I will buy low-salt crackers instead of saltines the next time I do the family grocery shopping”; or “I will ask my sister if she wants to go for a walk with me in the evening two times each week.” Family members can be guided through the goal setting process using motivational interviewing techniques that are effective with chronic illness patients, including encouraging realistic goals, assessing family members’ readiness to change their behavior, and discussing barriers to reaching the goal.(50–54)

In most family goal-setting programs, goals are set in the context of courses focusing on particular domains of patient self-management (i.e. medication taking, healthy eating, decision making).(55) Family is often instructed to choose patient support goals that relate to the topic of each session.(33, 40) In other goal-setting programs not taking place in conjunction with self-management courses, family members choose goals that support patient-identified areas of low self-efficacy(36) or goals that support patient goals previously identified through provider counseling. While families in most goal-setting programs choose goals that support patient health behaviors, family members could instead set goals to improve their own health, with the intention of creating a healthier home atmosphere which would in turn indirectly support and influence the patient.(43)

Examples from the Literature

In a program for lupus patients and their partners, patients completed questionnaires identifying areas of lupus management (such as pain management or medication adherence) in which the patient had low self-efficacy.(36) Program leaders then guided couples in generating solutions to the patient’s identified problems, and in setting partner goals to support patient goals for behavior change. These sessions were followed by five phone calls with the couple to evaluate progress and refine goals as needed. Compared to participants in a standard educational session, patients receiving the goal-setting intervention had greater improvements in fatigue, mental health, and perceived support, and clinically significant (but not statistically significant) improvements in physical functioning.

Some family goal-setting interventions have had less positive results. In two arthritis interventions in which patients and spouses set goals based on self-management program session content, patients participating with spouses had less improvements in fatigue, physical function, and pain than patients participating in the self-management course alone.(33, 40)

Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages of family member goal-setting include the definition of concrete actions family can take to support their loves ones. When family members have defined short-term goals, they may be more likely to carry out that specific role, recognize barriers to carrying out the role, and recognize incremental progress towards increasing their support for the patient. When planning ahead for situations in which patients are incapacitated and families need to take quick action, such as when patients are confused from low blood sugar or dizzy from a heart arrhythmia, setting explicit goals for action in that situation is more appropriate than learning general support techniques. Potential downsides of goal-setting programs are that the family member’s focus may be too narrow for the patient’s needs. For example, by focusing their support for diabetes care solely in terms of healthy food choices, family may miss opportunities to support the patient with other important areas of their self-care, e.g., glucose monitoring. Moreover, family members may not learn techniques that they can apply to other illness management situations as they arise.

Results of family member goal-setting programs tested to date are mixed, but their findings can guide future directions for family goal-setting research. In less successful interventional studies among patients with arthritis, families set goals focused on topics pre-determined by the interventionist, rather than on goals that are more patient-centered.(56–58) Future family goal-setting programs should work with family members and patients to set family support goals based on areas in which the patient desires and most needs support. Goal-setting programs may need to include training on ways to sustain family member goal setting over longer periods of time, including revising goals and building on achieved goals, to improve sustainability of this method of increasing family support. Finally, published programs about family goal setting have focused exclusively on patients with arthritis or rheumatologic disease. It is possible that patients with self-management needs that are likely to involve the larger family unit (such as healthier cooking), may benefit more from family goal-setting. Pilot goal-setting interventions for spouses of patients with diabetes(46) and hyperlipidemia(45) are underway.

Training Family Members in Supportive Communication and Coping Techniques

Definition and Rationale

Self-management of chronic illness requires managing changing symptoms and needs over time. In programs that teach family members general support techniques, such as how to help patients cope with symptoms or help motivate patients to stick with behavior goals, family members develop skills that can be adapted to new illness management problems as they arise. Such programs also encourage family to communicate more openly about illness symptoms and management, reflecting growing evidence that constructive family communication about illness management issues is linked to better patient self-management behavior,(59) while unresolved family conflicts about care can result in worse patient outcomes.(60–64) Programs that teach family members communication skills typically use cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques.(65) CBT based programs often give participants concrete examples of recommended ways to handle interactions with the patient about illness management and frequently include discussion or role play to assist family members in mastering these communication skills.

Examples from the Literature

A number of programs emphasize communication techniques family members can use that are more likely to be perceived as supportive (and not stifling) by independently functioning patients. One subset of these programs focuses on teaching family members how to prompt and reinforce patients’ use of symptom coping skills. For example, a family member may learn how to guide the patient with pain through a brief relaxation exercise or suggest an adaptation to a physical activity that the patient finds challenging. The two most extensively evaluated interventions of this type sought to enhance family support of patients managing arthritis symptoms and physical limitations. In coping skills training interventions carried out over 10–12 weeks, osteoarthritis patients participating with spouses had a trend towards improved pain levels, physical function, and mental health as compared to patients participating alone.(37–39) In another study, rheumatoid arthritis patients participating in a four week spouse-assisted coping skills training program had less joint swelling post treatment than randomized controls receiving the intervention without spouses or disease education with their spouses.(42) However, patients participating in this shorter duration intervention did not report significantly improved pain levels or functioning than controls.

Another type of family communication training program focuses on increasing spouse’s use of autonomy supportive communication techniques. Autonomy support emphasizes that the patient’s needs, feelings, and goals are the primary determinant of self-management success. While family can offer support, it is the patient who must ultimately ensure that illness management tasks are carried out. Therefore understanding the patient’s viewpoint and supporting their self-motivation is most important for illness management success. Autonomy-supportive behaviors include empathic statements that acknowledge the patient’s feelings and perspectives; offering choices and providing alternatives; providing a rationale for advice; and working together to problem-solve. Use of autonomy-supportive techniques has been associated with better patient outcomes,(57, 66, 67) and is particularly suited for supporting more functionally independent patients. Family use of behaviors that are not autonomy-supportive, including using pressure, criticism, or guilt to induce changes in patient behavior have been associated with worse patient outcomes.(62, 63)

In one example, the Family Partnership Intervention seeks to increase family member use of autonomy-supportive communication techniques to help heart failure patients improve their self care.(34, 35) Participants first receive an education session about heart failure care and techniques to decrease dietary sodium. Patients and family members then meet in separate small groups for two sessions that include didactic teaching about autonomy support, case scenarios, and role play. Family members identify the most autonomy-supportive response to scenarios representing difficult adherence situations. A newsletter reinforcing autonomy support strategies is mailed to participants several weeks after the session. Patients receiving the autonomy support intervention significantly decreased their intake of sodium compared to patients and families who participated in educational sessions alone. A larger trial evaluating the effects of this intervention on patient medication adherence, physical function, heart failure quality of life, and health care utilization is underway.(47) Another intervention incorporating autonomy supportive communication training for families of heart failure patients is also in progress.(44)

Advantages and Disadvantages

Initial evidence suggests that interventions focused on family prompting of patient coping mechanisms may be particularly suited to patients dealing with ongoing symptoms that affect patient quality of life, such as functional limitations from arthritis, dyspnea in COPD, or fatigue in heart failure. On the other hand, interventions focused on autonomy support may be particularly effective in supporting patients attempting to make health behavior changes.

Programs that teach family members general communication techniques may provide family with a broadly applicable communication toolset, allowing them to apply these skills to new illness management situations over time. However we do not know whether family members sustain their use of these techniques after programs end, or whether outcomes improve further when techniques are practiced and refined over time with feedback from professionals. A significant body of research from efforts to train health care professionals in more effective communication and behavioral change approaches has shown that initial training has to be reinforced with frequent booster sessions for the communication approaches to be sustained.(50) This likely will also be the case for interventions targeting family members. Learning illness-specific communication techniques may be more difficult and less effective for families with strained underlying relationships and communication patterns.

Involving Family Directly in Clinical Care Processes

Definition and Rationale

Family roles in supporting a chronically ill patient’s clinical care (i.e. appointments, testing, medication regimen changes, communication with professionals) can be very distinct from the roles family play in supporting patient maintenance of healthy behaviors. At clinic appointments, family members can help patients understand and remember information from providers. They can help the patient articulate their concerns clearly to clinicians and support the patient when bringing up difficult or embarrassing topics. Family members can help patients work with their clinicians to make fully informed decisions about changes in medical care, such as whether to start insulin or whether to undergo an arthroscopy. Between clinic visits family members can help with obtaining medication refills, managing appointments and insurance issues, maintaining self-testing or symptom logs and communicating those results to providers, and addressing worrisome trends in patient health at early stages. Through successful execution of these roles, family members can contribute to efforts to provide proactive chronic illness management that is better integrated among care providers, a key feature of the evidence-based chronic care model and proposals for a ‘medical home’.(68)

Family already frequently take on these clinical care-related roles, and many providers already include family members in their discussions with patients. New interventions have the opportunity to enhance family involvement in clinical care by helping patients and family members explicitly define family roles in clinical management, and by providing tools and skills that enhance family members’ ability to carry out these roles. For example, interventions could improve family member access to patient-related health information, provide structured or automated communication between providers and family members, or teach clinical skills to family members (such as how to properly take a blood pressure reading).

Examples from the Literature

The CarePartner program is an example of an intervention that gives family members specific roles in monitoring patient symptoms, self-testing, and medications.(41) The program also provides structured contact between out-of-home family members, chronic illness patients, and the patient’s health care provider through interactive automated telephone technology. At the beginning of the program, a selected family member is given written and online information about illness management. During the program, patients are called weekly by the automated service to complete a health assessment. During those calls, patients report information about their symptoms, nutritional intake, medication adherence, and availability of their medication supply. A report summarizing the patient’s responses to the assessment is automatically sent by email to the family member. The report highlights any concerning patient responses and suggests actions the family member can take, as well as a time frame for following up. As in many disease management programs, the patient’s clinical provider receives automated faxes summarizing more urgent health problems and can access the patient’s health assessment responses through a web site. Family members and clinicians can also leave messages for the patient that are delivered through the automated telephone system. After a 12-week pilot study with heart failure patients, over 70 percent reported that their participating family member helped them to solve self-management problems. The effect of the program on heart failure patients’ health-related quality of life, hospitalization risk, and self-care behaviors and a pilot study with diabetes patients are now being evaluated in randomized controlled trials.(48, 69)

Advantages and Disadvantages

Programs that help family members define specific roles in clinical care can make use of their presence at clinic visits and family members’ frequent desire to be kept informed of clinical information. These interventions also allow family members to assist with the more intense clinical monitoring that some patients need and that is not often practical for health systems to provide.

Programs that involve family in clinical care may face family member-provider communication difficulties. During clinic visits, family members may dominate discussions with providers (discouraging the patient from speaking)(70) or they may discuss their own medical problems beyond that relevant to the patient’s care (adding competing demands on the provider’s time). Patients often think family members miscommunicate with their health care provider and take on roles during the clinic visit that were different from what the patient intended.(70, 71) Future interventions need to evaluate the effects of training participants in effective provider-family communication skills.(72)

While family members in any support program may experience increased stress due to their intensified roles and role expectations, family members supporting clinical care may be particularly prone to increased stress or burden if they lack the clinical knowledge or skills they need to carry out their role, or lack effective access to the patient’s health care provider when needed. On the other hand, it is possible that family members will experience less burden and more satisfaction as a result of these programs if they feel they have the tools to be more effective in helping their loved one. Future clinical care support programs should seek to provide participating family members with appropriate skills and resources, and should monitor family burden as an outcome.

Future Research Directions

Further research is needed to identify programs that effectively mobilize family member support for chronic illness self-care. In general, recent studies have adhered to guidelines for best conduct of intervention trials. However most completed trials have had a relatively low number of participants (15–50 couples in each intervention arm), possibly limiting their power to detect significant changes in patient outcomes. Adequate recruitment is a challenge for all couple and family-based interventions, however interventions for chronic illness patients could be designed using recruitment strategies identified by other family-based psychosocial interventions (such as offering recruitment over the phone or in the participants’ home).(73) One limitation of several of the trials reviewed is that they did not measure change in the targeted family role or behavior (such as the number of family goals set or met, or decreases in the use of critical statements towards the patient). Analyzing how such changes in family behaviors and patients’ perceived disease-related support are related to changes in patient outcomes is essential to determining which intervention models are most promising.

Specific topics that should be addressed in future research on family support programs for patients with chronic illness include:

How are family support programs developed for one disease best applied to patients with other common chronic illnesses? For instance, while self-management is particularly important for improving outcomes among patients with diabetes, asthma, and coronary heart disease, there are few reports of family support programs for treatment of these illnesses.

Who benefits most from family support programs? For instance, are interventions more effective among patients with certain sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. men vs. women, younger vs. older)? Are interventions best targeted to patients with a more complex or unstable health status (e.g., uncontrolled symptoms, multiple comorbidities, or a recent hospital discharge), or to patients in the midst of making health behavior changes? Should family programs focus on patients in a maintenance phase of care, when short-term professional support has tapered?

How do family support programs affect outcomes other than patient health, such as family satisfaction or stress from providing support, patient-family relationships, health care provider burden, patient-provider relationships, and patient health service utilization?

Are multifaceted programs that combine goal-setting, communication skills, and tools to facilitate family involvement in clinical processes more effective than programs focusing on a single approach? For instance, family could set their own goals for facilitating patient behavior change while using autonomy supportive approaches to help patients through a challenging self-management situation, or a family member monitoring clinical symptoms could prompt coping techniques when the patient’s symptoms are bothersome but do not exceed the threshold for notifying the clinician.

How can family support programs address the needs of complex family systems, including family members living at a distance from one another, family members with negative relationships, or family members providing mutual support for similar chronic illness needs?

As we develop practice-based coordination of care (i.e. “medical homes”) (74) for patients with chronic illness, how can family support programs be best integrated with other clinical support services? How can interested family members be more integrated into clinical information flow (such as through access to personal health records)? How do we involve families while protecting patient privacy and avoiding adding excessive demands on already-stretched primary care providers?

Conclusion

Most current models of chronic illness care inadequately address the roles and influences of family in patient self-care even though family members are often well suited to provide effective support, and family support is associated with improved patient outcomes. Recent family support interventions directly address family member roles in illness management and seek to give family members the tools and skills they need to carry out these roles. The three emerging models for family support programs identified in this review (see Table 1 for summary) address the unique chronic illness support needs of adults without significant functional limitations. The few interventions evaluated to date have shown improvements in intra-family communication, levels of family support, and patient self-efficacy, and some have resulted in improved patient outcomes. These emerging models may be more effective if they incorporate a combination of approaches rather than testing a single strategy or when tailored to meet the needs of specific patient populations. Research on the best approaches to better mobilize family members to support chronic disease management is critically important, in light of the increasing numbers of patients with chronic disease, the difficulty of changing health behaviors and sustaining positive changes, limited resources for professional services, and a growing recognition of the positive effects of family support.

Acknowledgement

Ann-Marie Rosland was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program. John Piette is a VA Research Career Scientist. This study was supported by grant #DK020572 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. For comments on earlier versions of this manuscript we thank Michele Heisler and Maria Silviera. For discussing their innovative work and insights into family interventions in chronic illness we thank Patricia Clark, Sandra Dunbar, Lawrence Fisher, Lynn Martire, Stephen Sayers, Paula Trief, Ranak Trivedi, and Corrine Voils.

References

- 1.Norris SL, Nichols PJ, Caspersen CJ, et al. The effectiveness of disease and case management for people with diabetes. A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22(4 Suppl):15–38. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phillips CO, Wright SM, Kern DE, Singa RM, Shepperd S, Rubin HR. Comprehensive discharge planning with postdischarge support for older patients with congestive heart failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;291(11):1358–1367. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.11.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bott DM, Kapp MC, Johnson LB, Magno LM. Disease management for chronically ill beneficiaries in traditional Medicare. Health Affairs. 2009;28(1):86–98. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodenheimer T, Chen E, Bennett HD. Confronting the growing burden of chronic disease: can the U.S. health care workforce do the job? Health Affairs. 2009;28(1):64–74. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosland A-M. Sharing the Care:The Role of Family in Chronic Illness. [Accessed on 08-16-2009]; http://www.chcf.org/documents/chronicdisease/FamilyInvolvement_Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute for Family Centered Care. [Accessed on 08/11/2009]; http://www.familycenteredcare.org/faq.html. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laroche HH, Hofer TP, Davis MM. Adult fat intake associated with the presence of children in households: findings from NHANES III.[erratum appears in J Am Board Fam Med. 2007 Mar–Apr;20(2):241] Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine: JABFM. 2007;20(1):9–15. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.01.060085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trief PM, Sandberg J, Greenberg RP, et al. Describing support: a qualitative study of couples living with diabetes. Families, Systems & Health. 2003;21(1):57–67. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connell CM. Psychosocial contexts of diabetes and older adulthood: reciprocal effects. Diabetes Educator. 1991;17(5):364–371. doi: 10.1177/014572179101700507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sayers SL, Riegel B, Pawlowski S, Coyne JC, Samaha FF. Social support and self-care of patients with heart failure. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;35(1):70–79. doi: 10.1007/s12160-007-9003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gleeson-Kreig J, Bernal H, Woolley S. The role of social support in the self-management of diabetes mellitus among a Hispanic population. Public Health Nurs. 2002;19(3):215–222. doi: 10.1046/j.0737-1209.2002.19310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dowds BN, Bibace R. Entry into the health care system: the family's decision-making process. Fam Med. 1996;28(2):114–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silliman RA, Bhatti S, Khan A, et al. The care of older persons with diabetes mellitus: families and primary care physicians.[see comment] Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1996;44(11):1314–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosland A, Piette J, Heisler M. Incorporating Family Members Into Chronic Disease Clinical Care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;1(Supplement 1) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Moser D, Sanderman R, van Veldhuisen DJ. The importance and impact of social support on outcomes in patients with heart failure: an overview of the literature. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;20(3):162–169. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200505000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Strauman TJ, Robins C, Sherwood A. Social support and coronary heart disease: epidemiologic evidence and implications for treatment. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(6):869–878. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188393.73571.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffith LS, Field BJ, Lustman PJ. Life stress and social support in diabetes: association with glycemic control. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1990;20(4):365–372. doi: 10.2190/APH4-YMBG-NVRL-VLWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zautra AJ, Hoffman J, Potter P, et al. Examination of changes in interpersonal stress as a factor in disease exacerbations among women with rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;19(3):279–286. doi: 10.1007/BF02892292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen S. Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychol. 1988;7(3):269–297. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.7.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connell CM, Davis WK, Gallant MP, Sharpe PA. Impact of social support, social cognitive variables, and perceived threat on depression among adults with diabetes. Health Psychol. 1994;13(3):263–273. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warren BJ. Depression, stressful life events, social support, and self-esteem in middle class African American women. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1997;11(3):107–117. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(97)80033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallant MP. The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: a review and directions for research. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(2):170–195. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uchino BN. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med. 2006;29(4):377–387. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogan BE, Linden W, Najarian B. Social support interventions: Do they work? Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22(3):381–440. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. Jama. 2002;288(19):2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brereton L, Carroll C, Barnston S. Interventions for adult family carers of people who have had a stroke: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(10):867–884. doi: 10.1177/0269215507078313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hudson P. A conceptual model and key variables for guiding supportive interventions for family caregivers of people receiving palliative care. Palliat Support Care. 2003;1(4):353–365. doi: 10.1017/s1478951503030426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson CA, Spilsbury K, Hall J, Birks Y, Barnes C, Adamson J. Systematic review of information and support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paez KA, Zhao L, Hwang W. Rising out-of-pocket spending for chronic conditions: a ten-year trend. Health Affairs. 2009;28(1):15–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dashiff C, Hardeman T, McLain R. Parent-adolescent communication and diabetes: an integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62(2):140–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martire LM, Stephens MAP, Druley JA, Wojno WC. Negative reactions to received spousal care: predictors and consequences of miscarried support. Health Psychology. 2002;21(2):167–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bailey BJ, Kahn A, Bailey BJ, Kahn A. Apportioning illness management authority: how diabetic individuals evaluate and respond to spousal help. Qualitative Health Research. 1993;3(1):55–73. doi: 10.1177/104973239300300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riemsma RP, Taal E, Rasker JJ. Group education for patients with rheumatoid arthritis and their partners. Arthritis & Rheumatism-Arthritis Care & Research. 2003;49(4):556–566. doi: 10.1002/art.11207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clark PC, Dunbar SB. Family Partnership Intervention: A Guide for a Family Approach to Care of Patients With Heart Failure. AACN Clinical Issues. 2003;14(4):467–476. doi: 10.1097/00044067-200311000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Deaton C, Smith AL, De AK, O'Brien MC. Family education and support interventions in heart failure: a pilot study. Nursing Research. 2005;54(3):158–166. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200505000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karlson EW, Liang MH, Eaton H, et al. A Randomized clinical trial of a psychoeducational intervention to improve outcomes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2004;50(6):1832–1841. doi: 10.1002/art.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keefe FJ, Blumenthal J, Baucom D, et al. Effects of spouse-assisted coping skills training and exercise training in patients with osteoarthritic knee pain: a randomized controlled study. Pain. 2004;110(3):539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keefe FJ, Caldwell DS, Baucom D, et al. Spouse-assisted coping skills training in the management of osteoarthritic knee pain. Arthritis Care Res. 1996;9(4):279–291. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199608)9:4<279::aid-anr1790090413>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keefe FJ, Caldwell DS, Baucom D, et al. Spouse-assisted coping skills training in the management of knee pain in osteoarthritis: long-term followup results. Arthritis Care & Research. 1999;12(2):101–111. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199904)12:2<101::aid-art5>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martire LM, Schulz R, Keefe FJ, Rudy TE, Starz TW. Couple-Oriented Education and Support Intervention for Osteoarthritis: Effects on Spouses' Support and Responses to Patient Pain. Families systems & health. 2008;26(2):185. doi: 10.1037/1091-7527.26.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piette JD, Gregor MA, Share D, et al. Improving heart failure self-management support by actively engaging out-of-home caregivers: results of a feasibility study. Congest Heart Fail. 2008;14(1):12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2008.07474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radojevic V, Nicassio P, Weisman M. Behavioral Intervention With and Without Family Support for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Behavior Therapy. 1992;23:13–30. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wing RR, Marcus MD, Epstein LH, et al. A "family-based" approach to the treatment of obese type II diabetic patients. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(1):156–162. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sayers SL. A Family Intervention for Improving Self-Care of Patients With Heart Failure. [Accessed on 08/11/2009]; http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00645489?term=sayers&rank=2.

- 45.Voils CI, Yancy WS, Kovac S, et al. Study Protocol: Couples Partnering for Lipid Enhancing Strategies (couPLES) - a randomized, controlled trial. Trials. 2009;10(10) doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trief PM. Improving Diabetes Outcomes: A Couples Intervention. [Accessed on 9-08-2009]; http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00250731?term=trief&rank=3.

- 47.Dunbar SB. Education and Supportive Partners Improving Self-Care (ENSPIRE) [Accessed on 08/11/2009]; http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00166049?term=dunbar&rank=16.

- 48.Piette JD. Enhancing Caregiver Support for Heart Failure Patients: the CarePartner Study. [Accessed on 08/11/2009]; http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00555360.

- 49.Bradley EH, Bogardus ST, Jr, Tinetti ME, Inouye SK. Goal-setting in clinical medicine. Social Science & Medicine. 1999;49(2):267–278. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Britt E, Hudson SM, Blampied NM. Motivational interviewing in health settings: a review. Patient Education & Counseling. 2004;53(2):147–155. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heisler M. Helping your patients with chronic disease: Effective physician approaches to support self-management. Seminars in Medical Practice. 2005;8:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heisler M, Resnicow K. Helping patients make and sustain healthy changes: A brief introduction to the use of motivational interviewing approaches in clinical diabetes care. Clinical Diabetes. 2008;26(4):161–165. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rollnick SR, Mason P, Butler C. Health Behavior Change: A Guide for Practicioners. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, et al. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of General Practice. 2005;55(513):305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Resnicow K, Baskin M, Rahotep S, Periasamy S, Rollnick SR. Motivational interviewing in health promotion and behavioral medicine settings. Health Psychology. 2003;21(5):444–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams GC, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Supporting Autonomy to Motivate Patients with Diabetes for Glucose Control. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(10):1644–1651. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.10.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams GC, Rodin GC, Ryan RM, Grolnick WS, Deci EL. Autonomous regulation and long-term medication adherence in adult outpatients. Health Psychology. 1998;17(3):269–276. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fisher L, Weihs KL. Can addressing family relationships improve outcomes in chronic disease? Report of the National Working Group on Family-Based Interventions in Chronic Disease. Journal of Family Practice. 2000;49(6):561–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chesla CA, Fisher L, Skaff MM, Mullan JT, Gilliss CL, Kanter R. Family predictors of disease management over one year in Latino and European American patients with type 2 diabetes. Family Process. 2003;42(3):375–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fisher L, Chesla CA, Mullan JT, et al. Contributors to depression in Latino and European-American patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(10):1751–1757. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.10.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nicassio PM, Radojevic V. Models of Family Functioning and Their Contribution to Patient Outcomes in Chronic Pain. Motivation and Emotion. 1993;17(3):295–316. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Franks MM, Stephens MA, Rook KS, Franklin BA, Keteyian SJ, Artinian NT. Spouses' provision of health-related support and control to patients participating in cardiac rehabilitation. J Fam Psychol. 2006;20(2):311–318. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fisher L, Chesla CA, Chun KM, et al. Patient-appraised couple emotion management and disease management among Chinese American patients with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(2):302–310. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dobson D, Dobson K. Evidence-Based Practice of Cognitive-Behavioral Theory. 1st Edition. The Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Williams GC, Deci EL, Ryan RM. Building health-care partnerships by supporting autonomy: Promoting maintained behavior change and positive health outcomes. In: Suchman A, Hinton-Walker P, Botelho RJ, editors. Partnerships in healthcare: Transforming relational process. Rochester: University of Rochester Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Williams GC, Gagne M, Ryan RM, Deci EL. Facilitating autonomous motivation for smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 2002;21(1):40–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Affairs. 2001;20(6):64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gregor MA. QUERI Project: Enhancing Caregiver Support for VA Patients with Diabetes. http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/research/abstracts.cfm?Project_ID=2141698247&UnderReview=yes. Accessed on.

- 70.Ishikawa H, Roter DL, Yamazaki Y, Takayama T. Physician-elderly patient-companion communication and roles of companions in Japanese geriatric encounters. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(10):2307–2320. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ishikawa H, Roter DL, Yamazaki Y, Hashimoto H, Yano E. Patients' perceptions of visit companions' helpfulness during Japanese geriatric medical visits. Patient Education & Counseling. 2006;61(1):80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McDaniel S, Campbell T, Hepwroth J, Lorenz A. Family Oriented Primary Care. 2nd ed. Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fredman SJ, Baucom DH, Gremore TM, et al. Quantifying the recruitment challenges with couple-based interventions for cancer: applications to early-stage breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18(6):667–673. doi: 10.1002/pon.1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sidorov JE. The patient-centered medical home for chronic illness: is it ready for prime time? Health Affairs. 2008;27(5):1231–1234. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]