Abstract

One often overlooked aspect of nonviral gene therapy is the maintenance and localization of plasmids within a transfected cell. In this study we have quantified the nuclear retention of plasmids within microinjected cells after a single round of cell division. We employed several commercially available reagents to label plasmids with fluorophores for our microinjection tracking experiments. Interestingly, plasmids labeled with different techniques produced drastically different results. Naked plasmids microinjected directly into nuclei and later detected by in situ hybridization were found almost exclusively within the nuclei of the daughter cells after mitosis and were partitioned between the daughter nuclei with a normal, Gaussian distribution. Identical results were obtained with plasmids labeled with a fluorescent peptide nucleic acid. However, when plasmids were labeled with several commercially available fluorescent DNA labeling kits that randomly attach fluorophores to the entire plasmid and injected into HeLa cell nuclei, the modified plasmids were excluded from daughter nuclei after cell division. Taken together, these results suggest that naked, unmodified plasmids are retained in the nucleus following cell division and likely continue to express in the daughter cells. Our results demonstrate the significant alterations in episome localization that the labeling technique itself can have on plasmid trafficking.

Keywords: gene therapy, transfection, microinjection, plasmids, episomes, mitosis, peptide nucleic acid, fluorophores, nuclear import

Introduction

Among the many unknowns regarding the cell biology of the gene transfer process, the fate of episomal plasmids remains unresolved. For nonviral systems that neither integrate into host chromatin nor have viral proteins that mediate plasmid maintenance, it is important to understand and evaluate the ability of the vector to remain intact within a transfected tissue. Naturally, episomal DNA must persist if there is to be any prolonged level of gene expression. Studies have detected plasmids within mouse muscle a year after gene transfer and in the mouse liver after 3 months [1–3]. While mouse muscle seems to express transgenes indefinitely, expression levels in most other tissues and cells fall after a week or less despite plasmid persistence [4–6]. This rapid decrease in expression may be due to a variety of factors including DNA methylation, transgene repression, immune response to the produced transgene product, and plasmid maintenance and partitioning following mitosis.

The possibility exists that a dividing population of cells may be more likely to express transgenes for short periods of time because of two reasons. First, even though the plasmids may avoid degradation, the plasmid copy number per cell could eventually be diluted after several rounds of mitosis and plasmid partitioning. However, if the initial transfection is efficient, it would still take many rounds of division for expression levels to fall to baseline, since cells only need three plasmid copies per nucleus to express detectable transgene product [7,8]. The alternative reason is based on a previous study that showed that plasmids microinjected into the nucleus of a cell were subsequently excluded from the nuclei of the two daughters once the injected cell divided [8]. In this model, the plasmids may persist in transfected cells, but cannot be expressed since they do not reside within the daughter nuclei. The authors suggest that a small number of plasmids, below the limit of visual detection, could be retained in the daughter nuclei and account for the prolonged, but reduced, gene expression. On the other hand, plasmids excluded from the nuclei after mitosis could be reimported since cellular proteins are imported at a high rate immediately following the reestablishment of the nuclear envelope [9]. However, the crux of this problem is that if there are no plasmids retained within daughter nuclei after cell division, transgene expression should drop to near baseline levels after a single round of mitosis. At the very least, transgene expression should briefly cease while the plasmids are reimported into the nucleus at early times postmitosis. Based on numerous studies using different transfection agents, this does not appear to be the case [10,11].

A major reason for this discrepancy concerning plasmid movement and intracellular localization is that multiple DNA labeling techniques have been used and assumed to be interchangeable. Published plasmid tracking studies have employed several different commercially available products to label and detect plasmid DNA (pDNA), each with their own advantages and disadvantages [8,10,12–14]. For example, a number of cost-effective fluorescent tags that label DNA nonenzymatically and generate very bright signals by attaching fluorophores randomly throughout the entire plasmid [15–19] have been shown to affect transcriptional activity [18]. A likely explanation is that the bulky fluorophores coat the plasmid and block proteins, namely transcription factors, from binding to the DNA. Since a highly labeled plasmid has a lower expression level than an unmodified one, it is reasonable to suspect that the fluorophores could also affect plasmid trafficking and intracellular localization. Therefore, other DNA labels that attach to only a small defined region on the plasmid could be more favorable and allow normal protein–plasmid interactions to occur, thus painting a more accurate picture of true episome movement. Indeed, the labeling technique may have a greater influence on plasmid trafficking than the cellular proteins or plasmids themselves.

In this study, we have used a variety of plasmid labeling and detection methods to elucidate the localization of plasmids in dividing cells. Our experiments were designed to quantify the percentages of plasmids within daughter nuclei versus cytoplasm, as well as between the two daughter nuclei themselves. In addition, we asked whether plasmids are first excluded from the nuclei of daughter cells and subsequently reimported, as previously suggested [8], or if the plasmids are simply retained within the newly formed nuclei. Our results clearly demonstrate that the different DNA labeling and detection methods produced dramatically opposed results.

Results

Naked Episomes are Retained in Daughter Nuclei

To determine the fate of plasmids following mitosis, we microinjected the nuclei of isolated HeLa cells with the GFP-expressing plasmid pDD306 and determined the localization of the injected DNA by fluorescence in situ hybridization in the resulting daughter cells 12–18 h postinjection (Fig. 1). Since the injected cells were at least 200 μm apart from one another, we chose adjacent (i.e., daughter) cells that expressed GFP for analysis. It is important to note that even if plasmids were excluded from the nuclei after mitosis, the daughters would remain GFP positive since GFP fluorescence is observed within 35 min of nuclear plasmid injection and the GFP protein has a half-life of 24 h [20,21]. In almost all cells analyzed, the majority of the plasmids localized within the nuclei of HeLa daughter cells (Fig. 2). We obtained similar results using TC7 cells, a cell line derived from African green monkey kidney epithelium (data not shown). These results suggest that unmodified, native plasmids are retained within the nucleus following cell division.

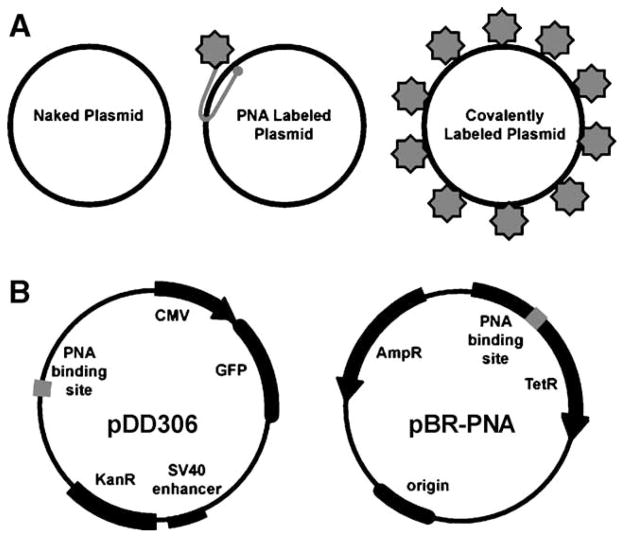

FIG. 1.

Plasmids and detection methods used. (A) Cartoon of plasmid labeling and detection methods used. Unmodified pDNA does not have any attached fluorophores and was detected in fixed cells by fluorescence in situ hybridization. A triplex-forming, Cy3-labeled PNA was used to label pDNA by base pairing to 8-mers within a specific 101-bp sequence on the plasmid. Label IT and Fast Tag fluorophores are covalently attached over the entire plasmid in a random fashion by differing chemistries. (B) Plasmids. pDD306 (pGFP) contains the GeneGrip1 PNA binding site cloned into pEGFP-N1 at the indicated site, away from cis-acting regulatory sequences. Similarly, pBR-PNA contains the GeneGrip1 PNA binding site cloned into pBR322, which lacks any eukaryotic regulatory or DNA nuclear targeting sequences.

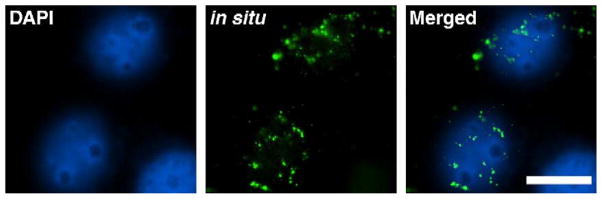

FIG. 2.

Naked pDNA injected into a HeLa nucleus remains nuclear following mitosis. HeLa nuclei microinjected with unmodified pGFP were allowed to divide and, 12–18 hours later, were fixed and processed for fluorescence in situ hybridization. An Oregon green-labeled probe (green) was used to visualize the injected plasmid by in situ hybridization and nuclear DNA was counterstained with DAPI (blue). Representative cells from multiple experiments are shown. Bar, 10 μm.

PNA-Labeled Plasmids Behave Like Naked Plasmids

Contrary to our findings using native plasmids, previously published data using randomly labeled plasmids have suggested that episomes are excluded from the nucleus after cell division [8]. To investigate this discrepancy, we desired a plasmid detection method that did not require any fixation or denaturation step, could be viewed in live cells, and would behave more like native plasmid. Consequently, we labeled plasmids using triplex-forming, Cy3-labeled peptide nucleic acids (Cy3-PNA) at a defined region (Fig. 1) [13,22]. We and others have demonstrated that PNAs can be used to label plasmids without altering the transcriptional or trafficking activities of the DNA and, further, that the PNAs do not dissociate from the intracellular, labeled plasmids during the time course of these experiments [13,23–25]. In the current experiments, 6 to 10 Cy3-PNAs were noncovalently attached to the 101-bp GeneGrip site 1 region of the plasmid pDD306. We microinjected the Cy3-PNA-labeled plasmid into the nuclei of HeLa cells and, 12–18 h later, viewed live cells by fluorescence microscopy to identify GFP-positive daughter cells and determine DNA localization. Images of live cells and the same exact cells following paraformaldehyde fixation were captured and showed identical plasmid localization patterns before and after fixation. As seen in two representative sets of divided cells (Fig. 3), the vast majority of the PNA-labeled plasmids were clearly localized within the daughter nuclei. We obtained similar results when TC7 cells and A7r5 (bronchial smooth muscle) cells were injected (data not shown). Taken together, the results obtained with a PNA-labeled plasmid confirm the results seen with unmodified plasmids, further suggesting that plasmids are retained within the nuclei after mitosis.

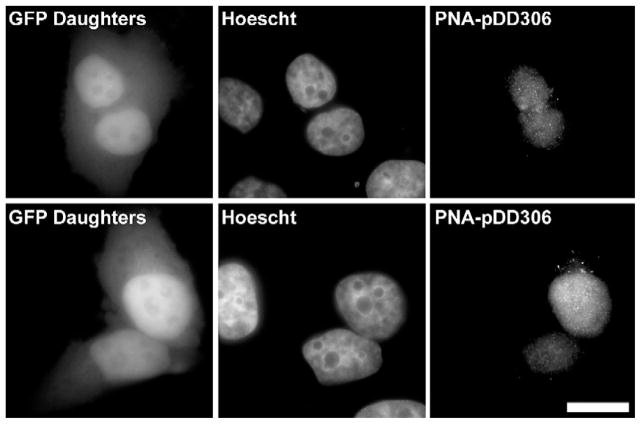

FIG. 3.

Nuclear-injected plasmid labeled with a fluorescent PNA is predominantly nuclear after cell division. Plasmid pDD306 labeled with a Cy3-PNA was microinjected into the nuclei of HeLa cells growing at least 200 μm apart. Twelve hours after injection, divided cells were visualized based on GFP expression in adjacent cells. Hoechst 33258 was used to visualize the nuclei and plasmids were visualized by Cy3 fluorescence. Representative daughter cells from multiple experiments are shown. Bar, 10 μm.

Plasmid Distribution Between Daughter Nuclei Is Relatively Equal

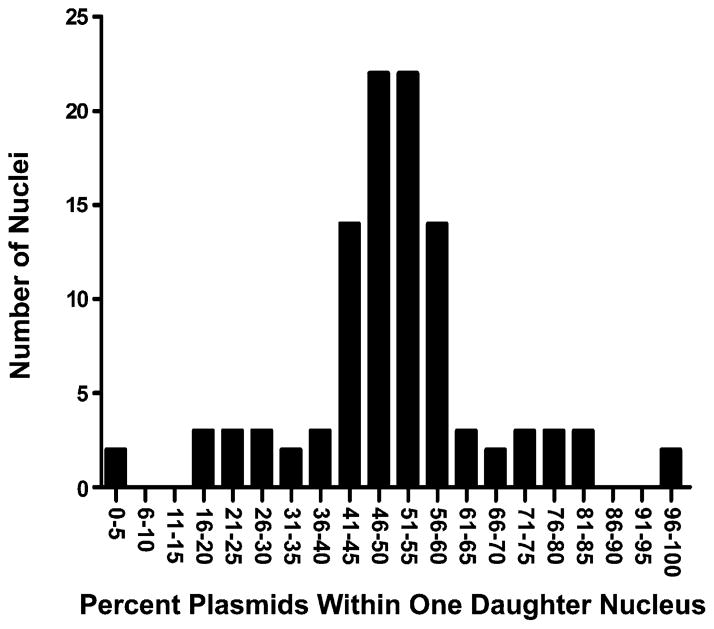

To determine whether the distribution of plasmids between the nuclei was relatively equal (Fig. 3, top) or disproportionate (Fig. 3, bottom), we analyzed all of the images obtained from the PNA injection experiments by quantifying plasmid fluorescence intensity in each daughter nucleus. For example, the relative percentages of plasmids in the two daughter nuclei shown in Fig. 3 are 52.1 and 47.9% (Fig. 3, top) and 60.4 and 39.6% (Fig. 3, bottom). We calculated the plasmid distribution in 106 individual daughter nuclei, representing 53 cell divisions, and plotted it as a histogram binned into 5% groupings (Fig. 4). As seen in the histogram, most cell divisions resulted in an even distribution of plasmids, plus or minus 10%, between the daughter nuclei. This suggests that the cells do not “imprint” the episomes in any way that would lead them to remain with only one of the nuclei.

FIG. 4.

Distribution of plasmids within daughter nuclei. The distribution of Cy3-PNA-labeled plasmids within divided cells was quantified in each daughter cell as described under Methods (n = 53 divisions, or 106 individual daughter nuclei). Plasmid distribution within each daughter nucleus was binned into 5% increments based on relative fluorescence.

Covalently Attached Fluorophores Alter Plasmid Localization Postmitosis

One possible explanation for the discrepancy between the results of Ludtke et al. [8] and those described above could be the method and degree of modification of the plasmids studied. To test this, we labeled the same plasmid used above with fluorophores using two different covalent methods at the same label-to-DNA ratios as previously described (Fig. 1) [8]. Label IT (Mirus Corp., Madison, WI, USA) randomly attaches fluorophores on the plasmids with an alkylating aromatic nitrogen mustard [26], whereas the Fast Tag system (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) randomly labels DNA but utilizes an aryl azide chemistry [19].

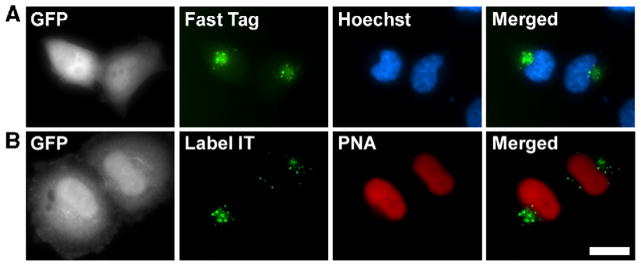

When we microinjected pDD306 labeled with either Label IT or Fast Tag (both at ratios of approximately 50 fluorophores per plasmid) into HeLa cell nuclei, the majority of the injected DNA was localized to the cytoplasm of divided daughter cells (Fig. 5A). Both labeling methods resulted in the same cytoplasmic distribution of nuclear-injected DNA after cell division, consistent with the previously published results [8]. To demonstrate further that the difference in subcellular localization was likely due to labeling methods, we co-injected Cy3-PNA-labeled pDD306 with Cy5 Label IT-modified pDD306 into the nuclei of cells. After a round of cell division, the PNA-labeled plasmid was found in the daughter nuclei while the Label IT plasmids were in the cytoplasm of the same cells (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Plasmids labeled with randomly attached fluorophores are excluded from the nucleus following cell division. (A) HeLa cell nuclei were injected with a mixture of Texas Red Fast Tag-labeled pDD306 and unmodified pDD306 and were allowed to divide. After cell division, daughter cells were identified on the basis of GFP fluorescence and the Fast Tag-labeled plasmids were localized in living cells (green). Nuclei were visualized with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Representative cells from multiple experiments are shown. (B) HeLa cell nuclei were injected with a mixture of pDD306 labeled with Cy5 Label IT reagent and Cy3-PNA-labeled pDD306 and were allowed to divide. After cell division, daughter cells were identified on the basis of GFP fluorescence and the Label IT-labeled (green) or PNA-labeled (red) plasmids were localized in living cells. Nuclei were visualized with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Representative cells from multiple experiments are shown. Bar, 10 μm.

We next quantified the relative amount of plasmids found within postmitotic HeLa cell nuclei for each of the detection methods used. We divided the sum of the total intensities for both daughter nuclei by the total amount of plasmid fluorescence in each pair of cells to generate the percentage of plasmids found within the nuclei. Table 1 shows that 69–80% of HeLa cells injected with either the Label IT- or the Fast Tag-labeled plasmids retained less than a quarter of the plasmids within their daughter nuclei. In half of these cases, the amount of plasmids retained in the sum of the two daughter nuclei was less than 10% of the total amount of pDD306 detected. In contrast, 72–84% of the cells injected intra-nuclearly with either unmodified or PNA-labeled plasmids retained almost all of the detected plasmids within their postmitotic nuclei. These data further support our hypothesis that bulky fluorophore groups randomly attached to plasmids can alter their normal trafficking and localization patterns.

TABLE 1.

Cellular distribution of plasmids postmitosis detected by different labeling methods

| Labeling method | 0–25% nuclear | 26–50% nuclear | 51–75% nuclear | 76–100% nuclear |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmodified | 0% | 8% | 8% | 84% |

| PNA | 0% | 2% | 26% | 72% |

| Label IT | 70% | 30% | 0% | 0% |

| Fast Tag | 69% | 26% | 0% | 5% |

The subcellular distribution of plasmids, by quartiles, following cell division was quantified in individual cells as described under Methods. The numbers represent all visualized divided cells in the experiments described in the text and figures for each labeling technique, Fast Tag (n = 19), PNA (n = 53), and Label IT (n = 10), and unmodified (n = 13). Compared to unmodified plasmids, the cellular distribution of Label IT- or Fast Tag-labeled plasmids was found to be statistically different by Mann–Whitney U test (P < 0.0001); there was no statistical difference in localization between unmodified and PNA-labeled plasmids.

Plasmids are Retained and Not Reimported into Daughter Nuclei

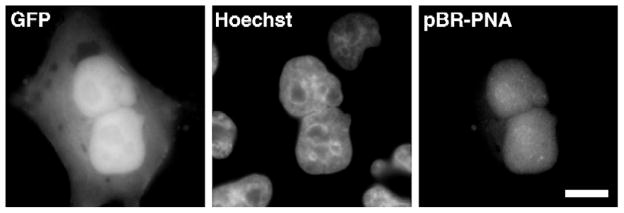

While these results demonstrate that native plasmids are found in the nuclei after mitosis, they do not provide insight into the mechanisms of nuclear “retention” of the plasmids. Thus, the plasmids could either be retained with the endogenous chromosomes while the nuclear envelopes reformed or first be distributed into the cytoplasm of the daughter cells and subsequently reimported into the newly formed nuclei. Because the plasmid pDD306 contains the SV40 enhancer sequence downstream of the GFP gene, this plasmid is actively transported in the nuclei of nondividing cells due to the DNA nuclear targeting activity of the SV40 enhancer [7,27]. Consequently, the plasmid pDD306 used in the above experiments could have been expelled into the cytoplasm after mitosis and then actively reimported into the nuclei afterward. By contrast, a plasmid lacking this import sequence will remain in the cytoplasm of a nondividing cell and, as such, could be used to distinguish nuclear “retention” from reimport. We created the plasmid pBR-PNA, which lacks a DNA nuclear targeting sequence and any other eukaryotic regulatory sequences that may facilitate nuclear retention, to contain a PNA-binding site and used it in a series of nuclear microinjections. When we injected a mixture of Cy3-PNA-labeled pBR-PNA and a small amount of unmodified pDD306 (used only to detect injected and divided cells) into HeLa cell nuclei, the labeled pBR-PNA plasmids were retained in the nuclei of the resulting daughter cells (Fig. 6). In 72% of the injected cells that divided, more than 75% of the pBR-PNA plasmids were found within the daughter nuclei. Since the pBR-PNA plasmid is incapable of being imported into the nucleus, the pBR-PNA plasmids must have remained associated with or near endogenous chromosomes as the nuclear envelopes reformed.

FIG. 6.

Nuclear-injected plasmids are not first excluded from daughter nuclei and then reimported. PNA-labeled pBR-PNA, which does not have any eukaryotic sequences and is not imported into the nucleus, was injected into HeLa cell nuclei. After cell division, the PNA-labeled plasmids were visualized in GFP-expressing daughter cells by Cy3 fluorescence. Bar, 10 μm.

Discussion

Our study followed pDNA localization after cell division. When we tracked naked pDNA initially microinjected into the nucleus, we found that the vast majority of it localized within the daughter nuclei (Fig. 2). Likewise, when we used a PNA clamp to label our plasmids fluorescently, the pDNA was also strongly localized to daughter nuclei (Fig. 3). Conversely, our experiments that tracked plasmids with covalently and randomly attached fluorophores showed that the pDNA was almost entirely excluded from the daughter nuclei after a single round of mitosis (Fig. 5), which is completely consistent with previous published experiments [8]. All these data are represented in Table 1. Taken together, these results suggest that the method of DNA labeling can have profound effects on the intracellular trafficking of DNA and that unmodified plasmids, as used in normal transfections and in vivo gene therapy approaches, do indeed remain in the nucleus following cell division.

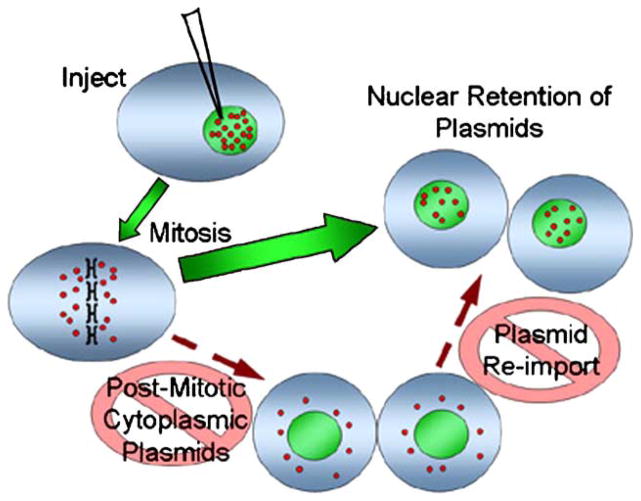

We have shown that when a transfected cell divides, the exogenous pDNA within its nucleus appears to partition evenly to the two new daughter nuclei (Fig. 4). Published studies have shown that episomal DNA will partition equally into daughter nuclei if viral proteins are present to tether the episome to chromatin. Epstein–Barr nuclear antigen-1 protein will maintain and equally partition a plasmid that contains the viral oriP region in cis by tethering it to endogenous chromatin [28–30]. Similarly, the circular SV40 genome has been shown to persist and be maintained in growing tumors when transcripts for large and small T antigens are present [31]. Based on the experiment shown in Fig. 6, it appears that episomes are at least somewhat associated with chromosomes when partitioned, even in the absence of viral protein components. The pBR-PNA plasmid is not imported into the nucleus and remains cytoplasmic when injected into the cytosol of a nondividing cell [27]. When a cell nuclearly microinjected with Cy3-PNA-labeled pBR-PNA undergoes a round of mitosis, the plasmids are primarily found within the daughter nuclei and are distributed between cells similar to the pDD306 plasmid. These data suggest that episomes, even in the absence of viral chromatin-associating systems, localize to the region of the cell designated to be enclosed by the reforming nuclear envelope during mitosis (Fig. 7). Alternatively, the newly divided cell could simply recognize the pDNA as a marker for nuclear envelope assembly as previous experiments have shown that functional nuclear envelopes will form around extrachromosomal DNA placed in chromosome-free cellular extracts [32,33]. A plasmid covered in randomly attached fluorophores may be recognized as a large, inert molecule and not as DNA to be enclosed within the new nuclei. Regardless of the mechanism, the end result means that transgene expression should remain constant in a dividing tissue because the plasmids are not excluded from the nuclei after mitosis.

FIG. 7.

Model of plasmid trafficking and localization in actively dividing cells. Plasmids injected into the nucleus of a cell are retained within the nuclei of daughter cells after a round of cell division. The results presented here suggest that the plasmids are not first excluded from the new daughter nuclei and subsequently reimported, but are rather retained in the nuclear “space” during mitosis.

We hypothesize that whenever a nonviral vector is labeled with large, bulky molecules throughout the entire plasmid sequence, cellular proteins are not able to bind to the plasmid. The loss of these interactions can greatly affect intracellular plasmid behavior. A previous study has shown that as the number of randomly attached fluorescent labels increases on a nonviral vector, the gene expression of that vector decreases [18]. Without a doubt, once exogenous plasmids are delivered into a cell, they begin to form macromolecular complexes with an assortment of proteins. A plasmid cannot be imported into the nucleus or transcribed without cellular proteins bound to it. Instead of being a molecule that is highly interactive with a range of cellular proteins, a plasmid coated with covalently attached fluorophores, biotin, or any other molecule appears to become a rather inert macromolecule and mimics the localization patterns of a large, benign dextran [8]. Interference by these covalent labeling methods and subsequent loss of protein–plasmid interactions most likely account for the drastic differences we observed.

Gene therapy as a whole could benefit greatly from continued plasmid trafficking research. Unfortunately, there is limited knowledge about what happens to plasmids once delivered to cells. Several recent papers have attempted to follow intracellular pDNA trafficking patterns in live cells with quantified microscopy [12,14]. However, these data were generated with plasmids randomly labeled with covalently attached fluorophores over the entire plasmid and it would be highly informative to follow plasmids detected by other methods to see if the conclusions are altered. This is not to say that covalent labeling techniques are inherently “bad.” Rather, these methods to label pDNA randomly are very simple and cost effective, making them attractive reagents to produce fluorescence probes easily, for in situ hybridization or gene chip arrays, for instance. However, they may not be suitable for all uses. Care must be taken to use reagents that will be appropriate and most effective for the experiments being designed. A more complete understanding of all aspects of plasmid trafficking could improve the efficiency of gene therapy, but it is important to recognize that the data obtained from pDNA tracking experiments could be skewed solely by the detection method itself.

Methods

Plasmids

The 5431-bp plasmid pDD306 was created by inserting a blunt fragment containing the GeneGrip1 PNA binding site (Gene Therapy Systems, San Diego, CA, USA) into the EcoO1091 restriction site of pEGFP-N1 (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The PNA site is about 1.5 kb upstream of the start of the cytomegalovirus immediate early promoter. The 4464-bp pBR-PNA plasmid was created by ligating a 101-bp GeneGrip1 PNA binding site linker (Gene Therapy Systems) into the BamHI restriction site of pBR322.

PNA labeling of plasmids

Plasmids pDD306 and pBR-PNA were labeled with Cy3-labeled PNA (Gene Therapy Systems) as described by the manufacturer. Briefly, plasmids were labeled with Cy3-PNA in the manufacturer’s labeling buffer at 37°C for 2 h followed by isopropanol precipitation to remove unbound Cy3-PNA. Plasmid labeling was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis and fluorescence detection in the absence of ethidium bromide.

Covalent labeling of plasmids

The Cy5 Label IT fluorescent tag was purchased from Mirus Corp (Madison, WI, USA).

The labeling reaction was carried out at a ratio of 0.5 μl of Label IT reagent to 1 μg of plasmid DNA for 1 h at 37°C followed by an ethanol precipitation step to remove unbound Label IT reagent as recommended by the manufacturer’s instructors [8]. Texas Red Fast Tag labeling reagent was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA, USA). The labeling reaction was carried out with at a DNA:Fast Tag reagent ratio of 1 μg DNA to 2 μl reagent with photocoupling as recommended by the manufacturer.

Cell culture

HeLa cells (cervical carcinoma, ATCC CCL-2) were grown in minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, antibiotics, and antimycotics. TC7 and A7r5 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, antibiotics, and antimycotics. Cells were subcultured with the selective mitotic detachment method and seeded into 175-μm Eppendorf CELLocate etched coverslips (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) in 12-well dishes and allowed to grow in a humidified 37°C incubator with 5% CO2 for 48 h until they reached 50–60% confluency.

Microinjection

Coverslips of cells were placed in 5 ml of fresh medium in a 60-mm dish. Labeled or unmodified plasmids were passed through a 0.22-μm filter, diluted in 0.5× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 68.5 mM NaCl, 1.3 mM potassium chloride, 5 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.2), and quantified spectrophotometrically. An inverted Leica (Wetzlar, Germany) microscope fitted with a 37°C acrylic incubation chamber and an Eppendorf Femtojet microinjection system was used to deliver plasmids (0.5 mg/ml) into nuclei with an injection pressure of 145 hPa for 0.3 s. Cells, at least 200 μm apart from one another, were microinjected to ensure that GFP-expressing doublet cells were daughters and not two separately injected cells. Approximately 50–75 cells within the Eppendorf CELLocate grid were microinjected for each experiment, and all experiments were performed multiple times. After microinjection, coverslips were returned to a humidified 37°C incubator and grown with 5% CO2 until the indicated time.

Plasmid in situ hybridization

Twelve to 18 h after microinjection, HeLa cells were rinsed with 1× PBS, permeabilized in 1× PBS plus 0.5% Triton X-100 for 45 s, fixed at −20°C in a 1:1 methanol:acetone solution for 5 min, and placed in 70% ethanol at 4°C overnight. Plasmid in situ hybridizations were carried out using a nick-translated DNA probe as previously described [27]. After fluorescence in situ hybridization, coverslips were washed for 15 min in PBS and mounted on slides with DAPI and the anti-fade reagent DABCO (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA).

Microscopy and image analysis

After microinjection with any labeled plasmid, images were captured in live cells on a Leica DMIRB inverted microscope with a 40× objective and/or the cells were rinsed in PBS and then fixed for 15 min in 3% paraformaldehyde, followed by 3 × 10-min washes in PBS and mounted with Hoescht 33258 and DABCO. Fixed cells and in situ hybridizations were observed under a Leica DMRXA2 epifluorescence microscope with a 100× objective (NA 1.35; Leica). Images were acquired with a Hamamatsu Ocra-ER 12-bit, cooled CCD camera (Hamamatsu, Japan) and OpenLab software (Improvision, Lexington, MA, USA). Images and plasmid localization were also validated by deconvolution with Improvision Velocity restoration software. Fluorescence was quantified with the OpenLab advanced measurements module and total intensity of a region of interest was calculated by multiplying the mean intensity by the total number of pixels. For Fig. 5 we created two regions of interest that outlined the daughter nuclear areas designated by the Hoechst stain in each image. The total intensity of Cy3-PNA-labeled plasmid pixels within each of the two nuclei was measured and individually divided against the summation of total intensity for both nuclei. The data in Table 1 were generated by measuring the sum of total PNA fluorescence intensity between both daughter nuclei and dividing that by the sum of PNA fluorescence intensity within both daughter cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH Grants HL59956 and HL71643. J.Z.G. was supported by NIH Grant EY07128-05 and a predoctoral fellowship from the Midwest Affiliate of the American Heart Association.

References

- 1.Herweijer H, Zhang G, Subbotin VM, Budker V, Williams P, Wolff JA. Time course of gene expression after plasmid DNA gene transfer to the liver. J Gene Med. 2001;3:280–291. doi: 10.1002/jgm.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolff JA, Ludtke JJ, Acsadi G, Williams P, Jani A. Long-term persistence of plasmid DNA and foreign gene expression in mouse muscle. Hum Mol Genet. 1992;1:363–369. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.6.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muramatsu T, et al. In vivo gene electroporation in skeletal muscle with special reference to the duration of gene expression. Int J Mol Med. 2001;7:37–42. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.7.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin JB, Young JL, Benoit JN, Dean DA. Gene transfer to intact mesenteric arteries by electroporation. J Vasc Res. 2000;37:372–380. doi: 10.1159/000025753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blair-Parks K, Weston BC, Dean DA. High-level gene transfer to the cornea using electroporation. J Gene Med. 2002;4:92–100. doi: 10.1002/jgm.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li S, et al. Increased level and duration of expression in muscle by co-expression of a transactivator using plasmid systems. Gene Ther. 1999;6:2005–2011. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean DA, Dean BS, Muller S, Smith LC. Sequence requirements for plasmid nuclear import. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:713–722. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ludtke JJ, Sebestyen MG, Wolff JA. The effect of cell division on the cellular dynamics of microinjected DNA and dextran. Mol Ther. 2002;5:579–588. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldherr CM, Akin D. The permeability of the nuclear envelope in dividing and nondividing cell cultures. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:1–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tseng WC, Haselton FR, Giorgio TD. Mitosis enhances transgene expression of plasmid delivered by cationic liposomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1445:53–64. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(99)00039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escriou V, Carriere M, Bussone F, Wils P, Scherman D. Critical assessment of the nuclear import of plasmid during cationic lipid-mediated gene transfer. J Gene Med. 2001;3:179–187. doi: 10.1002/jgm.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akita H, Ito R, Khalil IA, Futaki S, Harashima H. Quantitative three-dimensional analysis of the intracellular trafficking of plasmid DNA transfected by a nonviral gene delivery system using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Mol Ther. 2004;9:443–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zelphati O, Liang X, Hobart P, Felgner PL. Gene chemistry: functionally and conformationally intact fluorescent plasmid DNA. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:15–24. doi: 10.1089/10430349950019156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banks GA, Roselli RJ, Chen R, Giorgio TD. A model for the analysis of nonviral gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1766–1775. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Gijlswijk RP, et al. Universal Linkage System: versatile nucleic acid labeling technique. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2001;1:81–91. doi: 10.1586/14737159.1.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keller GH, Huang DP, Manak MM. Labeling of DNA probes with a photoactivatable hapten. Anal Biochem. 1989;177:392–395. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neves C, Byk G, Escriou V, Bussone F, Scherman D, Wils P. Novel method for covalent fluorescent labeling of plasmid DNA that maintains structural integrity of the plasmid. Bioconjugate Chem. 2000;11:51–55. doi: 10.1021/bc990070z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slattum PS, et al. Efficient in vitro and in vivo expression of covalently modified plasmid DNA. Mol Ther. 2003;8:255–263. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forster AC, McInnes JL, Skingle DC, Symons RH. Non-radioactive hybridization probes prepared by the chemical labelling of DNA and RNA with a novel reagent, photobiotin. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:745–761. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.3.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dean DA. Gene Delivery by Direct Injection and Facilitation of Expression by Mechanical Stretch. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zelphati O, et al. PNA-dependent gene chemistry: stable coupling of peptides and oligonucleotides to plasmid DNA. Biotechniques. 2000;28:304–310. 312–314, 316. doi: 10.2144/00282rr01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demidov VV, et al. Stability of peptide nucleic acids in human serum and cellular extracts. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;48:1310–1313. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson GL, Dean BS, Wang G, Dean DA. Nuclear import of plasmid DNA in digitonin-permeabilized cells requires both cytoplasmic factors and specific DNA sequences. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22025–22032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.22025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zelphati O, et al. PNA-dependent gene chemistry: stable coupling of peptides and oligonucleotides to plasmid DNA. Biotechniques. 2000;28:304–316. doi: 10.2144/00282rr01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belikova AM, Zarytova VF, Grineva NI. Synthesis of ribonucleosides and diribonucleoside phosphates containing 2-chloroethylamine and nitrogen mustard residues. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967;37:3557–3562. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4039(01)89794-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dean DA. Import of plasmid DNA into the nucleus is sequence specific. Exp Cell Res. 1997;230:293–302. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calos MP. Stability without a centromere. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4084–4085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sears J, Ujihara M, Wong S, Ott C, Middeldorp J, Aiyar A. The amino terminus of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) nuclear antigen 1 contains AT hooks that facilitate the replication and partitioning of latent EBV genomes by tethering them to cellular chromosomes. J Virol. 2004;78:11487–11505. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11487-11505.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sears J, Kolman J, Wahl GM, Aiyar A. Metaphase chromosome tethering is necessary for the DNA synthesis and maintenance of oriP plasmids but is insufficient for transcription activation by Epstein–Barr nuclear antigen 1. J Virol. 2003;77:11767–11780. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11767-11780.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krieg P, Amtmann E, Jonas D, Fischer H, Zang K, Sauer G. Episomal simian virus 40 genomes in human brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6446–6450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newmeyer DD, Lucocq JM, Burglin TR, De Robertis EM. Assembly in vitro of nuclei active in nuclear protein transport: ATP is required for nucleoplasmin accumulation. EMBO J. 1986;5:501–510. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newport J. Nuclear reconstitution in vitro: stages of assembly around protein-free DNA. Cell. 1987;48:205–217. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]