Abstract

Protein phosphatases, as the counterpart to protein kinases, are essential for homeostatic balance of cell signaling. Small chemical compounds that modulate the specific activity of phosphatases can be powerful tools to elucidate the biological functions of these enzymes. More importantly, many phosphatases are central players in the development of pathological pathways where inactivation can reverse or delay the onset of human diseases. Therefore, potent inhibitors for such phosphatases can be of great therapeutic benefit. In contrast to the seemingly identical enzymatic mechanism and structural characterization of eukaryotic protein kinases, protein phosphatases evolved from diverse ancestors, resulting in different domain architectures, reaction mechanisms and active site properties. In this review, we will discuss for each family of serine/threonine protein phosphatases, their involvement in biological process and corresponding strategies for small chemical intervention. Recent advances in modern drug discovery technologies have markedly facilitated the identification of selective inhibitors for some members of the phosphatase family. Furthermore, the rapid growth in knowledge about structure-activity relationships related to possible new drug targets has aided the discovery of natural product inhibitors for phosphatase family. This review summarizes the current state of investigation of the small molecules that regulate the function of serine/threonine phosphatases, the challenges presented and also strategies to overcome these obstacles.

Keywords: Serine/threonine protein phosphatase, drug design, structure-guided drug discovery, high throughput assay, small molecule inhibitors

The reversible phosphorylation of proteins represents a fundamental mechanism used by eukaryotic organisms with up to 30% of all proteins being phosphorylated at any given time [1, 2]. A host of biological functions are regulated through this mechanism including DNA replication, cell cycle progression, energy metabolism, cell differentiation, and development [3, 4]. Levels of cellular protein phosphorylation are controlled by protein kinases and phosphatases whose imbalance has been implicated in a variety of diseases including cancer, diabetes, cardiac hypertrophy, and neurodegeneration [5]. Protein kinases have become a mainstay in the portfolios of almost every pharmaceutical company as one of the most attractive drug targets [6-8]. The tremendous progress that has been made in the development of kinase inhibitors for clinical use has invigorated discussions of the possibility of protein phosphatases being drug targets.

Although promising, rational design for phosphatase inhibitors present a variety of challenges primarily rooted in the way phosphatases evolved. In humans, protein phosphorylation predominantly occurs on tyrosine, serine and threonine residues with phosphoserine accounting for most of the phosphorylated sites (86.4%), followed by threonine (11.2%), and finally tyrosine being the least abundant (1.8 %) [9]. Corresponding to the large percentage of phosphorylation on serine/threonine residues, protein serine/threonine phosphatases (PSPs) regulate many biological processes including metabolism [10], responses to microbial and viral infections [11], mitosis [12-14], protein synthesis [15], transcription [16], and many other biological pathways [17]. Interestingly, despite the overwhelming demand for dephosphorylation and its obvious biological importance, there are only 43 PSPs in the human genome, a mere 10% of the number of kinases [18].

Therefore, rather than simply matching each serine/threonine kinase with a phosphatase to reverse the modification, phosphatases have evolved diversified strategies to coordinate their function with that of kinases to act upon a greater variety of substrates. The primary strategy evolved in nature is one of combination, where PSPs may “mix'n match” a limited number of catalytic subunits with a large number of regulatory subunits. Each catalytic subunit can combine with a variety of regulatory subunits to achieve the high selectivity required for accurate signal transduction. The regulatory subunits can control the cellular localization, substrate selection, and phosphatase activity of the catalytic subunits. In this manner, a small number of PSP catalytic subunits may process many phosphorylated serine and threonine residues within the cell. This combinatorial approach, in which different regulatory and catalytic subunits form a variety of functioning holoenzymes, makes it challenging to regulate phosphatase function with small chemical compounds. Additionally, nature amplifies the substrate recognition capacity of PSPs by generating a variety of isoforms during transcription. Next Generation Sequencing combined with proteomic analysis has been used to identify the prevalence of such isoforms [2].

Despite challenges inherent to PSP inhibitor design, a variety of approaches hold promise for the future. The availability of genomic databases and Next Generation Sequencing technologies provide powerful tools to better understand the biological function of phosphatases and therefore increase our ability to effectively design specific inhibitors. The availability of large chemical libraries and automatic high throughput screens facilitate the identification of de novo scaffolds. These scaffolds can be expanded using combinatorial chemistry techniques to quickly generate focused chemical libraries. Computer-aided drug optimization is playing an important role in facilitating rational design against a variety of protein templates. By combining these techniques, scientists can effectively screen large scaffold libraries, modify promising scaffolds, and optimize small molecules rationally to effectively inhibit phosphatases. These modern drug discovery techniques [19] have and will aid in the development of specific and powerful PSP inhibitors.

The three families of PSPs present different challenges for drug design

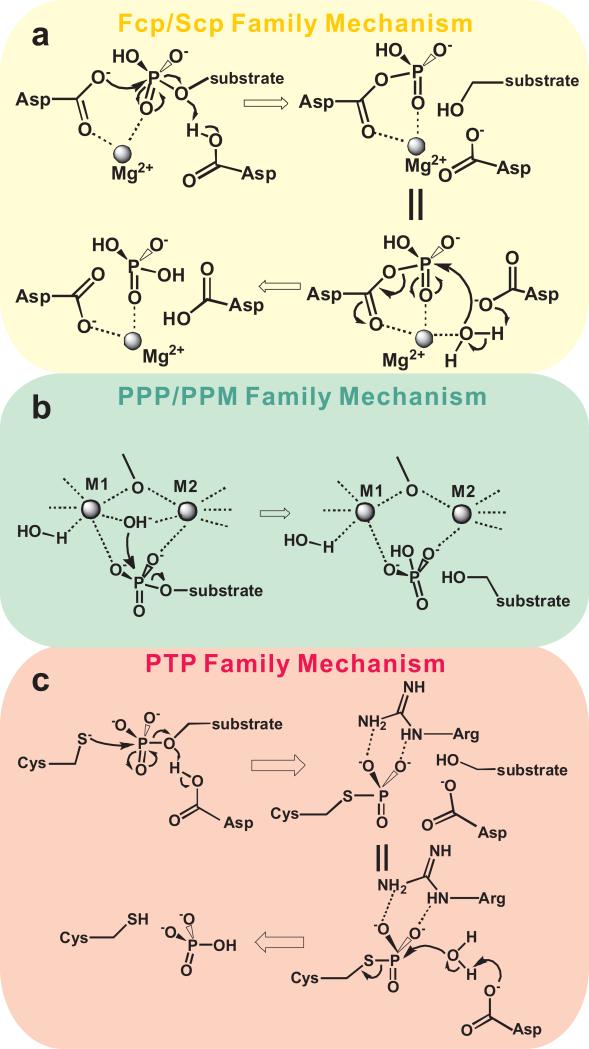

In order to rationally design a specific strategy for each family of PSPs, it is critical to start with an understanding of their structures and enzymatic mechanisms. Three families of PSPs are classified based on their reaction mechanisms (Figure 1), domain architectures, and three-dimensional structures [20]: aspartate-based phosphatases such as Fcp/Scp, Mg2+- or Mn2+-dependent protein phosphatases (PPMs) and phosphoprotein phosphatases (PPPs).

Figure 1. Catalytic mechanisms of different families of protein phosphatases.

(a) For the Fcp/Scp family, the active site Mg2+ and DxDx(T/V) motif are essential for the phosphate transfer. In this mechanism, the first aspartate in the DxDx(T/V) motif makes a nucleophilic attack to the phosphate group of the substrate in the first step, forming a phospho-aspartyl intermediate which is subsequently hydrolyzed in the second step. (b) For both the PPP and PPM family, two metal ions are coordinated at the active site to mediate the phosphate transfer without forming an intermediate. These metals could be Magnesium, Manganese, Iron, Zinc, or any combination thereof. A hydroxyl ion bridging the two metal ions takes part in nucleophilic attack on the phosphate group of the substrate. (c) For PTPs, which are metal-independent Cys-based phosphatases, an active site cysteine serves as the nucleophile which attacks the phosphate group, forming a phospho-cysteinyl intermediate.

Fcp/Scp family phosphatases, like other members of the haloacid dehydrogenases (HAD) superfamily, require the presence of a metal ion (Mg 2+) in the active site for catalysis (Figure 1a). Since they are single-subunit proteins with their substrate selectivity encoded locally near the active site, they are a strong candidate for modern drug discovery methods.

The PPM family phosphatases are Mg2+- or Mn2+-dependent enzymes that are also mostly single-subunit proteins (Figure 1b) [21]. Modern drug discovery strategies have been applied to some of the well-established disease-related PPMs with early stage success [22, 23]. However, their bioavailability and potency need to be improved for medical application [23]. Furthermore, the high sequence identity in PPM isomers complicates the situation due to the demand of highly selective isoform-specific inhibitors [21].

The third family is the PPP family, which is the major workhorse in cells for dephosphorylation of serine/threonine residues in proteins. The PPP family of phosphatases functions as multi-subunit complexes in vivo which are composed of a catalytic subunit and multiple regulatory subunits. Substrate specificity is determined by both catalytic and regulatory subunits, posing a huge challenge for selective inhibitor design. Instead of rational design, as seen with the Fcp/Scp or PPM families, natural chemical compounds have been identified that regulate the activity of these enzymes. Using these natural products as a starting point, scientists are seeking compounds that exhibit better pharmacological properties with less toxicity [24].

In the rest of this review, we will discuss efforts for the discovery of small molecule modulators for each individual family of PSPs and information regarding their mechanisms, structures, and disease implications. Endeavors to develop inhibitors of PTPs are summarized elsewhere [25] (Figure 1c).

Fcp/Scp family inhibitors

The Fcp/Scp family phosphatases belong to the HAD superfamily which includes more than 3,000 enzymes sharing the DXDX motif to facilitate the chemical reaction but with diversified biological functions centering around the transfer of a phosphate group in an O-P or C-P bond [26]. Fcp/Scp family proteins transfer the phosphate group of serine/threonine residues utilizing a mechanism involving a phospho-aspartyl intermediate that requires a single Mg2+ ion (Figure 1a). The formation of this phosphoaspartyl intermediate is a key feature that distinguishes the Fcp/Scp family members from other metal-dependent phosphatases (Figure 1a). A two-step mechanism of the Scp1-mediated phosphorylation reaction has been proposed and the phospho-aspartyl intermediate has been captured in crystal structure confirming its proposed mechanism [27] (Figure 1a). This mechanism shows a resemblance to the reaction mechanism of protein tyrosine phosphatases in which a phosphoryl-cysteine intermediate is formed, though a coordinated metal ion is not required for PTP activity (Figure 1c).

The best-characterized members of this family are the transcription factor IIF (TFIIF)-interacting CTD phosphatase 1 (Fcp1) and the small CTD phosphatases (Scp1-3). The predominant substrate identified for both enzymes is the C-terminal domain (CTD) of eukaryotic RNA polymerase II (Pol II), which orchestrates transcription and couples it to other cellular events including mRNA capping and processing, DNA repair, etc. [28]. The CTD is composed of multiple tandem heptapeptide repeats ranging from 26 repeats in yeast to 52 in human. The heptapeptide has a strictly conserved sequence: Tyr1Ser2Pro3Thr4Ser5Pro6Ser7, where Ser2 and Ser5 are the primary phosphorylation sites during the transcription cycle. The phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of these two sites, Ser2 and Ser5, exhibit stringent and conserved temporal regulation during every round of transcription [29, 30].

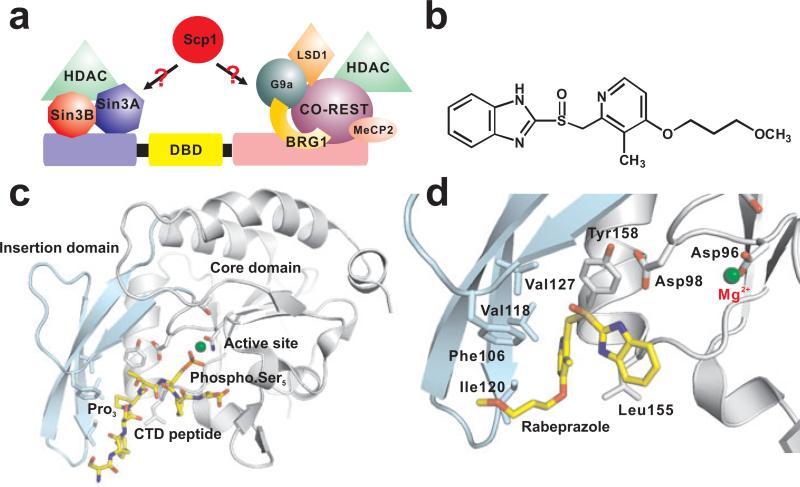

Emerging evidence suggests that Scp1 functions as a co-repressor associated with the repressor element 1 (RE-1)-silencing transcription factor (REST) complex to silence the expression of some neuronal genes in neuronal stem cells and in non-neuronal cells [31] (Figure 2a). Four lines of evidence support that the inhibition of Scp1 can be a powerful strategy to promote neuronal regeneration. First, inactivation of Scp1 by a dominant negative mutant Asp96Glu/Asp98Asn can induce neuronal differentiation in mouse P19 embryonic stem cells [31]. Secondly, microRNA-124, which directly targets the untranslated regions of Scp genes, can antagonize the anti-neural effect of Scp1 and stimulate neuronal differentiation [32]. Thirdly, a recent study demonstrated that knockdown of the RNA-binding protein PTB, a protein which can prevent microRNA-124 from binding to Scp genes, induced neuron-like differentiation in six different types of cells [33]. Moreover, knockdown of Scp1 similarly induced neural differentiation [33]. Therefore, inhibition of Scp1 by small molecules has the potential to promote neuronal differentiation for both academic research and clinical application.

Figure 2. Structure and inhibition of Scp1.

(a) Domain architecture of REST protein and REST-interacting proteins involved in the formation of the REST complex, a master regulator for neuronal gene silencing. Scp1 has been found to be associated with the complex but the binding partner of Scp1 is yet to be identified. (b) Chemical structure of rabeprazole, the first selective inhibitor for the Fcp1/Scp1 family. (c) Complex structure of Scp1 and a short Ser5-phosphorylated CTD peptide (PDB code: 2ght). The insertion domain is highlighted by light cyan. The active site is indicated by the essential Mg2+ ion shown in green. DxDx(T/V) motif and the hydrophobic pocket residues are shown in stick. (d) Zoom-in of the Scp1 hydrophobic pocket binding to the inhibitor rabeprazole.

Because the homologue of Scp1, Fcp1, is an essential enzyme for regulating Pol II recycling during general transcription and whose inactivation will compromise the viability of cells [34] , the requirement for the selectivity of Scp1 inhibitors is high. Fcp1 is a CTD phosphatase conserved throughout eukaryotes with a preference for Ser2 of the CTD as substrate [29, 34, 35]. On the other hand, Scps are the CTD-specific phosphatases present in higher eukaryotes [36] which exhibit strong catalytic preference toward Ser5 rather than Ser2. In humans, Scp1 shares 24% sequence identity with Fcp1 in the phosphatase domain with a similar tertiary fold [37, 38]

In order to design a small molecule inhibitor that selectively inactivates Scp1 without interfering with Fcp1 activity, structural studies of these enzymes were carried out [37, 38]. Crystal structures show that the catalytic domains of Scp1 and Fcp1 have a similar overall fold [39]. Interestingly, a small region composed of about 40 amino acids is the most divergent area in the primary sequence [38]. In Scp1, this region folds into a three-stranded β-sheet (Figure 2c) and is reminiscent of a WW domain, which is a structural motif that recognizes proline residues. Indeed, the complex structure of Scp1 with a substrate CTD peptide showed that a proline residue is bound at this site (Figure 2c). This so called “insertion domain” plays an essential role in determination of selectivity for Ser5 by Scp1 as demonstrated by mutagenesis study [38]. More importantly, the sequence of the insertion domain is highly diversified within the Fcp/Scp family, and therefore, the Pro3-binding hydrophobic pocket, which is partially formed by the insertion domain, is unique to Scp1 (Figure 2c). Consequently, it was proposed that small chemical compounds that predominantly target this pocket would be selectively bound by Scp1 with little cross-inhibition against other members of the Fcp/Scp family [38, 40]. Based on this rationale, a selective small molecule inhibitor has been identified for Scp1, and this is also the first selective inhibitor for the Fcp/Scp family [40]. The inhibitor, rabeprazole (Figure 2b), is a synthetic compound that was initially identified by high throughput screening. Indeed, rabeprazole binds to the hydrophobic pocket and exhibits high selectivity toward Scp1 [40] (Figure 2d). It inhibits Scp1 with an IC50 around 9 μM and a Ki of 5 μM when tested with a malachite green assay using a CTD peptide as the substrate (Table 1) without inhibiting the two close family members of Scp1, Fcp1 and Dullard which is a trans-membrane PSP. The complex structure of Scp1-rabeprazole shows that the sulfoxide group and methyl pyridine ring of rabeprazole contribute most to the interaction [40] (Figure 2d ). The sulfur atom makes a cation-π interaction with the phenol ring of Tyr158 of Scp1. Elimination of this cation-π interaction by mutating Tyr158 to Ala resulted in at least a ten-fold loss of inhibition [40].

Table 1.

Inhibition potency of the small molecule inhibitors toward each family member of PSPs

| Small molecule inhibitors | Target phosphatase | Ki or IC50 | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rabeprazole | Scp | 5μM (Ki) | [40] |

| sodium salt of 1-amino-9,10-dioxo-4-(3-sulfamoylanilino1) anthracene-2-sulfonic acid | PHLPP2 | 5.45 ± 0.05 μM (IC50) | [61] |

| 1,3-[[4-(2,4-diamino-5-methylphenyl) diazenylphenyl]hydrazinylidene]-6-oxocyclohexa-1,4-diene-1-carboxylic acid | 3.7 ± 0.06 μM (IC50) | ||

| Okadaic acid | PP1 | 15-50nM (IC50) | [68] |

| PP2A | 0.1-0.3nM (IC50) | ||

| PP2B | 4μM (IC50) | ||

| PP4 | 0.1nM (IC50) | ||

| PP5 | 3.5nM (IC50) | ||

| PP6 | 0.lnM | [147] | |

| PP7 | >1μM (IC50) | [148] | |

| Microcystin-LR | PP1 | 0.3-1nM (IC50) | [76] |

| PP2A | <0.1-1nM (IC50) | ||

| PP2B | 1μM (IC50)) | ||

| PP4 | 0.15nM (IC50) | ||

| PP3 | 1nM (IC50) | ||

| PP6 | 0.lnM | [147] | |

| PP7 | >1μM (IC50) | [148] | |

| Calyculin A | PP1 | 0.4nM (IC50) | [149] |

| PP2A | 0.25nM (IC50) | ||

| PP2B | >1μM (IC50) | ||

| PP4 | 0.4nM (IC50) | ||

| PP3 | 3nM (IC50) | ||

| PP6 | 1 nM | [147] | |

| PP7 | >1μM (IC50) | [148] | |

| Tautomycin | PP1 | 0.23-22nM (IC50) | [130] |

| PP2A | 0.94-32nM (IC50) | ||

| PP2B | 1μM (IC50) | ||

| PP4 | 0.2nM (IC50) | ||

| PP3 | l0nM (IC50) | ||

| Fostriecin | PP1 | 45-58μM (IC50) | [24] |

| PP2A | 1.5-5.5nM (IC50) | ||

| PP2B | l00μM (IC50) | ||

| PP4 | 3.0nM (IC50) | ||

| PP3 | 30-70μM (IC50) | ||

| FK3G6 | PP2B | >30nM (IC50) | [151] |

| Cycloporin A | PP2B | 65nM (IC50) | [152] |

| Sanguinarine | PP1 | 42.5μM (IC50) | [62] |

| PP2A | >100μM (IC50) | ||

| PP2B | 77μM (IC50) | ||

| PP2C | 2.5μM (IC50) | ||

| Phosphonothioic acid | PP2Cα | 15μM(Ki) | [63] |

The success of the targeted inhibitor design for Scp1 is attributed to the uniqueness of this enzyme. Firstly, Fcp/Scp family enzymes have a much smaller repertoire of substrates and, therefore, toxic effects may be less detrimental. The CTD is the only well-characterized substrate for Scp1, even though other potential targets have been reported for Scp1, for example Smad [41]. Secondly, the insertion domain has evolved as a structural element to implement selectivity for Ser5 over Ser2, therefore, compounds targeting this domain can be used to differentially inhibit Scp1 without strong cross-inhibition against Fcp1. Overall, Scp1 inhibitors show great promise to be used for neuronal stem cell differentiation. However, the caveat that the knockdown of Scp1 converts fibroblast to neurons raises the concern of side effects on non-neuronal cells. Biological analysis of genes regulated by Scp1 in neural stem cells versus non-neural cell types will shed light on the differentiated effect of Scp1 on various cell types and is being actively pursued.

PPM small molecule regulators

Like Fcp/Scp family phosphatases, PPMs are single-subunit phosphatases that can utilize Mg2+ (or both Mg2+ and Mn2+) ion for catalysis. However, PPMs exhibit an active site totally different from Fcp/Scp because two metal ions, known as the bi-metal center, activate a water molecule for direct transfer of the phosphate group of a substrate, as shown in the first structure of PP2C the founding member of PPM [21] (Figure 1b and Figure 3a,b).

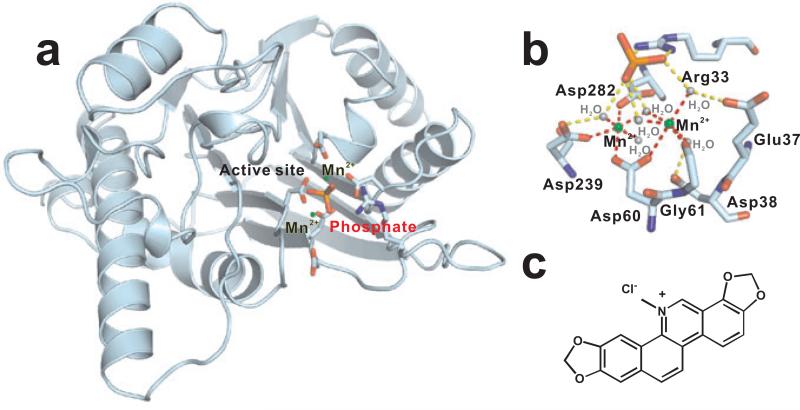

Figure 3. Catalytic mechanism of PPM phosphatase.

(a) N-terminal catalytic domain (1-290 residues) of mammalian PP2C (PDB ID 1a6q) shown in cyan where binuclear Mn2+ ion (green) site indirectly coordinates a phosphate ion (magenta) to form the catalytic site. Four invariant aspartate residues Asp38, Asp60, Asp239, and Asp282 in addition to Arg33, Glu37, and Gly61, coordinating the catalytic sites are shown as sticks. (b) Catalytic site in A is magnified where six water molecules (grey) and residues situated in β-sandwich structure coordinate Mn2+ ions to coordinate the phosphate group of the substrate (c) Structure of Sanguinarine, a natural plant product identified to potently inhibit PP2C.

Although PPMs generally consist of a single domain, the challenge in inhibitor design arises from the wide range of isoforms, contributing to a large repertoire of substrates with different signaling outcomes. For example, PP2Cδ (also named Wip1, or PPM1D) has dominant oncogenic effects in cells by turning-off the function of a handful of tumor suppressor proteins [42-44], whereas PP2Cα, PP2Cβ and PH domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase (PHLPP) have been identified as tumor suppressors [45-47].

Wip1, the protein product of the oncogene PPM1D, attracts the most attention as an anticancer drug target in the PPM family. Evidence has implicated Wip1 as a key player in oncogenesis [48]. Firstly, the PPM1D gene is amplified and overexpressed in 15% of human breast cancer [49, 50] as well as in several other cancers such as neuroblastma, pancreatic adenocarcinomas, ovarian and gastric carcinomas [51, 52]. Secondly, the inactivation of Wip1 in vitro in human cancer or neuroblastoma cell lines greatly decreases their viability [53]. Thirdly, depletion of the PPM1D gene in mouse mammary gland tumors in vivo promotes apoptosis [54]. Furthermore, PPM1D null mouse embryo fibroblasts are resistant to transformation [55]. Finally, detailed analysis has revealed that Wip1 plays a key role in ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated)-CHK2 (checkpoint kinase 2) [44] and MAPK pathways [55] by its negative regulation on p53 [56, 57]. These factors together establish Wip1 as a good target for anti-tumor drug discovery.

In order to identify selective inhibitors for Wip1, a high throughput phosphatase assay was established and a set of 14 compounds were identified as potential inhibitors [22]. These compounds can effectively prevent the dephosphorylation of substrates with no effect on PP2Cα or PP2A. In vivo, these inhibitors reduce the rate of proliferation of breast cancer cells and decrease proliferation and development of xenograft tumors in mice [22]. This set of experiments provides the proof-of-concept that selective inhibitors for Wip1, which do not interfere with homologue enzymes such as tumor suppressor PP2Cα, are feasible. In another strategy, substrate-based cyclic phosphopeptides were designed as the competitive inhibitors for Wip1 [23]. Even though their negative charge makes the inhibitors less cell permeable, therefore less likely to be applied in medical intervention, the rationale of using a cyclic framework to reduce the entropy penalty seems to enhance the potency of the inhibition and can be applied to future inhibitor study [23].

Contrary to Wip1, several PP2C family phosphatases are reported to have tumor suppression properties that are not desirable as inhibitor drug targets. On the other hand, chemical compounds inhibiting these proteins can be used as a chemical tool to study down-stream pathways and identify the substrate pool regulated by these enzymes [58]. The availability of the PP2Cα structure makes it applicable to structure-guided inhibitor design (Figure 3a) [21]. Virtual ligand screening was applied successfully to the inhibitor designs for several PP2C family members. Small molecule micromolar inhibitors of PP2Cα were identified. These represent the first non-phosphate-based molecules found to inhibit a type 2C phosphatase [59]. PHLPP has emerged as a central component in suppressing cell survival by both inhibiting proliferation and promoting apoptosis [60]. Small molecule inhibitors were identified by medium throughput chemical screening and virtual screening to inactivate PHLPP [61]. Two compounds, 1-amino-9,10-dioxo-4-(3-sulfamoylanilino1) anthracene-2-sulfonic acid and (1,3-[[4-(2,4-diamino-5-methylphenyl) diazenylphenyl]hydrazinylidene]-6-oxocyclohexa-1,4-diene-1-carboxylic acid, selectively inhibited PHLPP2 activity in vitro with IC50 values of 5.45 ± 0.05 and 3.70 ± 0.06 μM, respectively [61]. The application of modern drug discovery methods has led to the identification of inhibitor leads for PPM family phosphatases. Further optimization of these leads and analysis of their biological effects are in process.

Sanguinarine, a plant alkaloid, was identified as a potent and selective inhibitor of PP2Cα [62] (Figure 3c). It shows PP2Cα inhibition activity at a Ki value of 0.68 μM and is better than the earlier reported PP2Cα inhibitor phosphonothioic acid with Ki of 15μM [63]. However, PP2Cα is not the only target of this natural product. Sanguinarine was also shown to inhibit the mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 activity (MKP-1, dual phosphatase) [58]. In vivo, sanguinarine induced p38-mediated apoptotic cell death in HL60 cells, possibly deriving from a combinational effect towards its multiple targets [58].

The establishment of some PP2C members as tumor suppressors invigorates the search of small molecule activators. Compared to inhibitors, activators are harder to identify for several reasons. First, virtual screen tends to be ineffective for activator design since most activators function allosterically. Second, the enzymatic assay depends on the increase of output signal whose quantification demands higher level of accuracy. Third, false positives can arise when small compounds stabilize the enzyme folding in vitro but such effect tends to be erased in vivo. Nevertheless, a large screen was set up to identify chemical compounds that promote the dephosphorylation reaction mediated by PP2Cα. A small molecule activator, NPLC0393, can prevent liver fibrosis through its enhancement of PP2C activity by negatively regulating the TGFβ signaling pathway and the cell cycle [64].

PPP small molecule modulators

To process most of the phosphorylated serine/threonine residues (which account for 98.2% of overall phosphorylations in vivo), PPP family phosphatases utilize a combinatorial mechanism to handle a large number of dephosphorylations. This family is divided into seven subfamilies, which differ in their subunit architectures but conserved in their catalytic domain structure and mechanism (Figure 1b and Figure 4b).

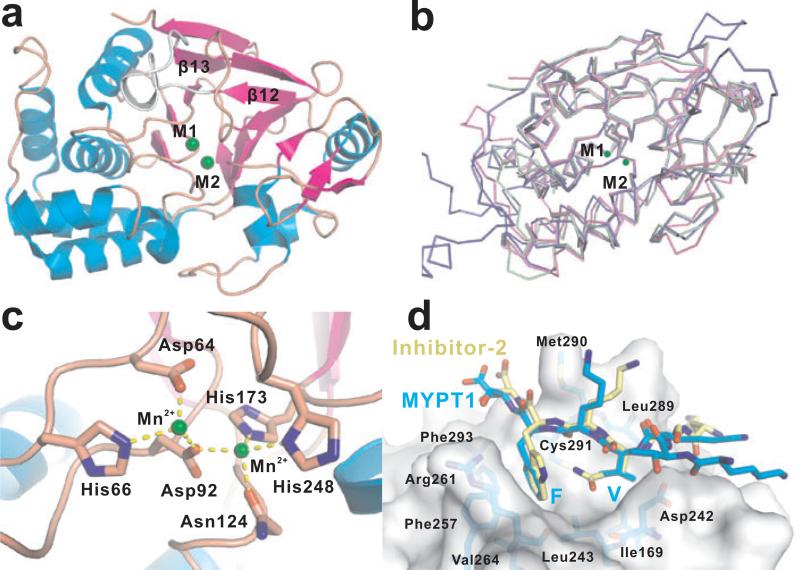

Figure 4. Structures of PPP family phosphatase catalytic subunits.

(a) Overall fold of the catalytic subunits of the PPP family phosphatases as represented by the PP1 catalytic subunit (PDB code: 1jk7). The β12-β13 loop is highlighted by white and the two metal ions in the active site are highlighted by green spheres. (b) Superimposition of PP1, PP2A, PP2B catalytic subunits, indicating they are well conserved. The PP1 backbone is depicted as pink coil, PP2A in green and PP2B in blue. (c) Zoom-in of the active site of PP1 (PDB code: 1jk7). The six active site residues are strictly conserved through all PPP family phosphatases. Notably, the metal ions could be magnesium, manganese, iron, zinc, or any combination thereof. (d) RVxF/W-binding pocket of PP1 binding with superimposed RVxF/W motifs of inhibitor-2 (PDB code: 2o8g) and regulatory subunit MYPT1 (PDB code: 1s70). Important residues forming the RVxF/W-binding pocket are labeled and shown in stick under the surface representation.

As would be expected for enzymes that form such extensive and intricate complexes, PPP enzymes act upon a large number of substrates; therefore, de novo rational inhibitor design at first seemed unfeasible to selectively inhibit PPP holoenzymes in specific pathological pathways. Thus, scientists initially sought inspiration from Nature, as a handful of natural products were discovered to effectively inhibit PPP holoenzymes. Most of these compounds, also known as natural toxins, inactivate PPP enzymes by binding to the highly conserved active site, resulting in the largely global inhibition of Ser/Thr dephosphorylation and, as a consequences, cellular function. Luckily, recent scientific endeavors have focused on compounds that can selectively regulate individual PPPs. We will discuss those advancements individually.

Non-selective inactivation of PPP at the catalytic active site by natural toxins

Compounds that eliminate the activity of PPPs are powerful tools to identify the broad repertoire of PPP substrates and in turn, elucidate signaling pathways for biological functions. About a dozen natural toxins have been identified to inhibit PPP family members, such as okadaic acid, microcystin-LR, calyculin A, nodularin, and tautomycin (Figure 5, Table 1). PP1 and PP2A subfamilies were the first identified to be the targets of natural toxins. PP4, PP5 and PP6 were later shown to be effectively inhibited by these compounds with different affinities (Table 1). In contrast, PP2B (calcineurin) and PP7 appear significantly less responsive to toxin inactivation.

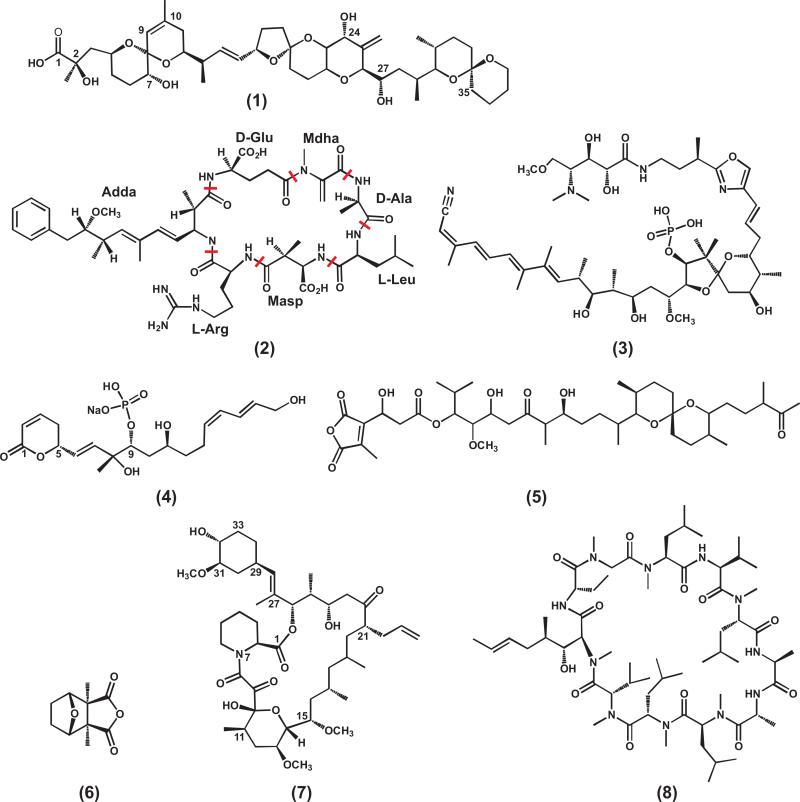

Figure 5. Chemical structures of natural toxins that inhibit PPP family phosphatases.

(1) Okadaic acid; (2) Microcystin-LR with the red lines separating each amino acid component; (3) Calyculin A; (4) Fostriecin; (5) Tautomycin; (6) Cantharidin; (7) FK506; (8) CsA.

These toxins associate tightly with the catalytic center that is well conserved within the PPP family, along with the two metal ions they coordinate. The catalytic subunits of the PPP family adopt a compact α/β fold with a central β-sandwich consisting of multiple β-strands arranged between two α-helical bundles [65] (Figure 4a). The active site is located at the joint of the loop of the three β-sheets of the β-sandwich, where two metal ions are coordinated by three histidines, two aspartates, and one asparagine (Figure 4c). These six residues, highly conserved in all members of the PPP family, are referred to as a binuclear metal center. A water molecule that bridges the two metal ions is activated and initiates the nucleophilic attack on the phosphorous atom of the substrate [66] (Figure 1b).

Okadaic acid (Figure 5, compound 1), a monocarboxylic acid characterized as the causative agent of diarrhetic shellfish poisoning in humans, was the first identified selective small molecule inhibitor for toxin-sensitive PPPs [67]. Bialojan and Takai conducted detailed specificity and kinetic studies on the inhibitory effect of okadaic acid on PP1, PP2A, PP2B and PP2C phosphatases [68] (Table 1). It was found that okadaic acid has a relatively high specificity for PP1 and PP2A with the most potent inhibitory effect for PP2A (IC50 0.1 nM) compared to PP1(IC50 around 15 nM) [69]. Despite sharing a similar folding and catalytic mechanism, PP2B is inhibited to a much lesser extent (IC50 4 μM) (Table 1).

The crystal structure of PP1 bound with okadaic acid [70] elucidates the mechanism for the potent inhibition (Figure 6a). Okadaic acid inactivates the enzyme by binding to its binuclear metal center. In PP1, the active site is located at the center of three grooves, from which emanate three grooves on the surface of the protein, termed hydrophobic, C-terminal, and acidic grooves (Figure 6a). Okadaic acid has a hydrophobic spiroketal moiety and an acidic moiety that forms a cyclic structure stabilized by an intramolecular hydrogen bond between the C-24 hydroxyl and the C-1 acid (Figure 5, compound 1). The hydrophobic moiety accounts for the high potency of the toxin with chemical groups with similar hydrophobicity also found in other PPP natural toxins such as microcystin-LR and calyculin A. Mutagenesis studies also showed that the hydrogen-bonding interactions between okadaic acid and Tyr272, Arg96 and Arg221 are also important as demonstrated [70] (Figure 6b).

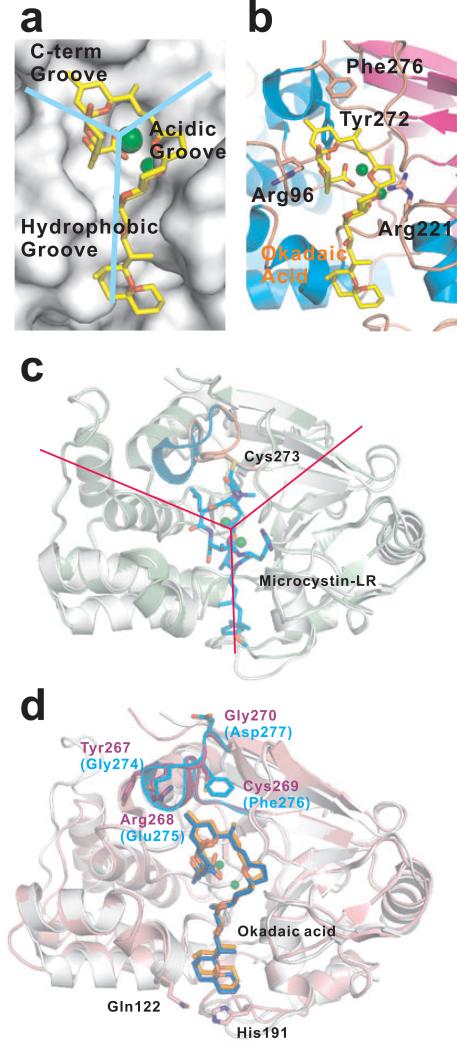

Figure 6. Structures of PPP binding with natural toxin inhibitors.

(a) Surface representation of PP1 binding to okadaic acid and the Y-shaped grooves emanating from the dimetalic center (PDB code: 1jk7). (b) Important residues that form the okadaic acid binding pocket of PP1. (c) Superimposition of PP1-microcystin-LR (PDB code: 1fjm, palegreen) and PP1-okadaic acid (PDB code: 1jk7, white) showing the difference at the β12-β13 loop and the covalent bond between Cys273 and microcystin-LR. For clarity, the okadaic acid is not shown. The β12-β13 loop in PP1-microcystin-LR structure is highlighted in pink, whereas the one in PP1-okadaic acid structure is in cyan. The red lines indicated the three grooves emanating from the dimetalic center. (d) Superimposition of PP1 (PDB code: 1jk7, white) and PP2A (PDB code: 2ie4, pink) catalytic subunits bound with okadaic acid (colored blue in PP1 and orange in PP2A). The β12-β13 loop in PP1 is highlighted by cyan, and the one in PP2A is highlighted by violet. Residues Gln122 and His191 that makes the hydrophobic cage in PP2A are shown in stick. The dimetalic center is indicated by green spheres.

Interestingly, even with the high conservation of active site residues, okadaic acid displays a much higher potency against PP2A relative to PP1 (150 fold) [71] (Table 1). Because of this, most of the cellular effects caused by okadaic acid are usually attributed to the PP2A-associated pathways. The inhibition potency and preferences can be elegantly explained by subtle differences at the active site [72]. The primary difference lies in the β12- β13 loop that is important for toxin binding (Figure 4a and Figure 6d) [73]. Indeed, mutation of Phe276 of this loop in PP1 to cysteine (corresponding residue in PP2A) reduced the Ki by about 40-fold for okadaic acid [74] (Figure 6b). The hydrophobic groove adjacent to the active site, which accommodates the hydrophobic moiety of these tumor-inducing toxins, is more optimally shaped in PP2A due to the existence of an additional hydrophobic cage [72]. Specifically, His191 and Gln122 in PP2A contribute to the hydrophobic cage and mediate van de Waals interaction with the toxin [70] (Figure 6d).

Another group of natural toxins frequently used in phosphatase studies is microcystin. This family of toxins are a group of cyclic heptapeptides isolated from cyanobacteria [75]. They were later identified to potently inhibit the catalytic subunits of both PP1 and PP2A [69, 76, 77]. So far, there are more than 80 known microcystin variants with microcystin-LR being the best characterized (Figure 5, compound 2). Unlike okadaic acid which preferentially inhibits PP2A, microcystin-LR inhibits PP1 and PP2A equipotent with an IC50 value of 0.2 nM [77] (Table 1). The major difference between the inhibitory mechanisms of okadaic acid and microcystin is that microcystin-LR forms a covalent bond with a cysteine residue of the protein after hours of incubation [78, 79] (Figure 6c). However, mutagenesis studies on PP1 and PP2A showed replacement of cysteine residues has little effect on inhibition by microcystin-LR in vitro [80]. Therefore, the covalent bond formation is not requirement for the inhibition of microcystin mechanism.

In addition to these two best characterized toxins, the interaction between PPP catalytic subunits with several other natural toxin inhibitors were analyzed using structural studies, including PP1 with calyculin A [81] (Figure 5, compound 3), motuporin(nodularin-V) [82], nodularin-R and tautomycine [83] (Figure 5, compound 5) and PP2A with dinophysistoxin [84]. All available complex structures of PPP enzymes with natural toxins are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Crystal structures of Phosphatases with natural products

| Phosphatase | Complex constituents | Toxin | PDB Code | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP1 | α Isoform, Catalytic Subunit | Microcystin | 1FJM | [65] |

| PP1 | γ Isoform, Catalytic Subunit | Okadaic acid | 1JK7 | [70] |

| PP1 | γ Isoform, Catalytic Subunit | Calyculin A | 1IT6 | [81] |

| PP1 | γ Isoform, Catalytic Subunit | Motuporin | 2BCD | [82] |

| PP1 | γ Isoform, Catalytic Subunit | Dihydromicrocystin-LA | 2BDX | [82] |

| PP1 | α Isoform, Catalytic subunit | Nodularin-R | 3E7A | [83] |

| PP1 | α Isoform, Catalytic subunit | Tautomycin | 3E7B | [83] |

| PP2A | AB'C holoenzyme and Shugoshin | Microcystin-LR | 3FGA | [153] |

| PP2A | regulatory subunit A (PR 65) α isoform, catalytic subunit α isoform | Microcystin LR | 2IE3 | [72] |

| PP2A | regulatory subunit A (PR 65) α isoform, catalytic subunit α isoform | Okadaic acid | 2IE4 | [72] |

| PP2A | regulatory subunit A (PR 65) α isoform, catalytic subunit a isoform | Dinophysistoxin-1 | 3K7V | [84] |

| PP2A | subunit A (PR 65), alpha isoform catalytic subunit alpha isoform | Dinophysistoxin-2 | 3K7W | [84] |

| PP2B;Calci neurin | ternary complex of calcineurin A calcineurin B, Cyclophilin A | Cyclosporin A | 1MF8 | [133] |

| PP2B | ternary complex of a calcineurin A calcineurin B, and FKBP12 | FK506 | 1TCO | [131] |

| PP2B | ternary complex of a calcineurin A calcineurin B, and FKBP12 | FK506 | 1AUI | [154] |

| PP5 | Catalytic domain | Cantharidic acid | 3H62 | [155] |

| PP5 | Catalytic domain | Cantharidin | 3H63 | [155] |

| PP5 | Catalytic domain | Cantharidic Acid | 3H67 | [155] |

| PP5 | Catalytic domain | Cantharidin | 3H68 | [155] |

Regulating individual PPPs with small molecules

The catalytic subunits of PPP have broad substrate specificity. It is only upon association with regulatory and/or targeting subunits that PPP holoenzymes exhibit substrate preferences. Therefore, compounds that prevent the assembly of particular holoenzymes will only affect a subset of the substrates, achieving the desired selective pharmacological inhibition towards PPPs. However, designing small molecules for protein complexes is very challenging [85]. Unlike targeting a well-defined active site pocket, inhibitors of protein complexes must deal with a large area of surface contacts that tends to be flat with no grooves and/or pockets suitable for small molecule binding [85]. To circumvent this problem, scientists sought inspiration from selective protein inhibitors of PPP enzymes. The majority of regulatory proteins, including protein inhibitors, utilize a “molecular Lego” strategy in which holoenzyme complex of PPP phosphatases are formed at a combination of surface patches [86]. Synthetic compounds can be developed to bind these patches, achieve specific exclusion of certain binding partners, and prevent the dephosphorylation of target substrates.

PP1 inhibitors

PP1 is a major eukaryotic PSP that plays critical roles in an enormous variety of cellular processes such as cell cycle progression, protein synthesis, carbohydrate metabolism, and apoptosis [15, 87-89]. PP1 is ubiquitously distributed in cells and functions by forming highly specific holoenzyme between the catalytic subunit and over 50 different established or putative regulatory subunits [87]. In a recent bioinformatics study, the number of regulatory subunits for PP1 was predicted to be more than 200 [90]. The highly diversified array of regulatory subunits targets the catalytic subunit to different subcellular locations and increases activity toward particular substrates. Usually, the regulatory subunit and catalytic subunit form a complex in a stoichiometric ratio of one to one. Interestingly, most PP1 regulatory subunits are intrinsically disordered and follow a “folding upon binding” mechanism [91]. Therefore, the only way to understand the binding interaction is through the observation of complex formation between catalytic and regulatory subunits of PP1 [88]. Structural information for the PP1 holoenzyme has only recently started to emerge, e.g. MyPT1:PP1 (PDB code: 1s70) [92, 93], spinophilin:PP1 (PDB code: 3egg) [94-96], Neurabin:PP1 (PDB code: 3hvq) [94] and NIPP1:PP1 (PDB code: 3v4y) [97].

A canonical motif found in more than 95% of the PP1 regulatory subunits, called RVxF/W motif, binds to an RVxF/W binding groove of the catalytic subunit of PP1 (Figure 4d). This RVxF/W recognition groove is only conserved in the PP1 catalytic subunit, therefore, compounds targeting this binding groove will not cross-regulate other PPP family catalytic subunits, providing the desired selectivity. The first glimpse of how this regulatory element binds the PP1 catalytic subunit was achieved by determining the structure of a peptide containing an RVxF/W motif in complex with the PP1 catalytic subunit [98]. Compounds targeting this RVxF/W groove have been shown apparently activation effect of phosphatase activity. Small molecules designed to mimic the RVxF motif showed a modest two fold activation in phosphatase activity [99]. In a cell-based assay, a compound identified through a focused peptide-based library targeting the RVxF allosteric binding site inhibits HIV-1 through “activation” of PP1 [100]. One explanation for the observed effect is that the binding of these small chemical compounds prevent the assembly of the PP1 holoenzyme, leaving the catalytic subunit free to act on any substrate it encounters. Alternatively, the binding of such small molecules at the RVxF/W groove stabilizes PP1 catalytic domain and result in an improved activity.

Pioneering work for selective inhibition of a PP1 holoenzyme was carried out in a high throughput screening assay in which salubrinal was identified to inhibit the dephosphorylation of eIF2a by the GADD34/PP1 complex [101]. Salubrinal effectively prevents the assembly of GADD34/PP1 holoenzyme, although the compound recognition site on either protein subunit is still unknown [101]. Another small molecule, guanabenz, an α2-adrenergic receptor agonist used in the treatment of hypertension, can prevent the assembly of the PP1 catalytic subunit with its regulatory subunit PPP1R15A/GADD34 by binding to the regulatory subunit [102]. Even though the mechanism of the molecular interaction between compounds and PP1 holoenzyme subunits has not been resolved, it shows that targeting the region of interaction between the regulatory subunit and the PP1 catalytic subunit outside the RVxF/W binding pocket is a potential effective approach for the selective inhibition of PP1 holoenzyme assembly and, in turn, activity.

PP2A regulators

PP2A is another important PSP that accounts for the majority of PSP activity in mammalian cells. PP2A has been implicated in cell growth, metabolism and signaling [103, 104], so its deregulation can lead to a number of diseases, including cancer [105] and Alzheimer's Disease [106]. The discovery that the catalytic subunit of PP2A is a cellular target of the tumor-inducing toxin okadaic acid led to the identification of PP2A as a tumor suppressor [107]. Indeed, disrupting the phosphatase activity of PP2A results in cell transformation. Spontaneous mutations in PP2A have also been identified in several human cancers [108].

In cells, the PP2A catalytic subunit (C subunit) associates with the scaffolding subunit (A subunit) to form a heterodimeric core enzyme; various regulatory subunits (B subunits) then associate with the core enzyme to form a heterotrimeric holoenzyme (ABC) [103]. The regulatory B subunits can be divided into four families, and each family contains two to five isoforms encoded by different genes. Although the regulatory subunits are highly conserved within each family, they share little sequence similarity across families. Additionally, the expression levels of regulatory subunits vary significantly in different cell types and tissues. The diversity of regulatory subunits confers versatility to PP2A phosphatases.

Activating the enzymatic activity of PP2A has attracted a lot of interest for potential medical application due to its function as a tumor suppressor. Like many PPP enzymes, the PP2A catalytic domain is also subject to inhibition by natural protein inhibitors, therefore, blocking the inhibitor protein from binding would be an effective strategy for enhancing PP2A activity with high selectivity. One of the inhibitor proteins for PP2A, SET protein, is a nuclear protein fused to the nucleoporin Nup214 that plays a role in acute non-lymphocytic myeloid leukemia [109, 110]. In vitro experiments using recombinant proteins determined that the IC50 of SET for inhibition of PP2A was 2 nM. In contrast, up to 20 nM SET did not affect the activities of recombinant PP1, PP2B and PP2C [111]. Because of this discovery, inhibition of SET binding has become an attractive target for novel therapeutic approaches to cancer treatment. Small molecules which can interfere with SET and activate the tumor suppressor PP2A have been identified including ceramide [112] and FTY-720 [113]. Recently, several novel PP2A inhibitor proteins have been identified, such as Cancerous Inhibitor of PP2A (CIP2A) [114], ENSA and Arpp19 [115, 116]. Blocking inhibitor proteins from binding the tumor suppressor PP2A is thus a promising strategy to enhance PP2A activity.

Surprisingly, the identification of PP2A as the target of an anti-tumor agent, fostriecin, shifts the paradigm that PP2A cannot be considered as a drug target [117]. Fostriecin is an antibiotic produced by Streptomyces pulveraceus (Figure 5, compound 4). It inhibits PP2A strongly with an IC50 of 3.2 nM while exhibiting very weak inhibition toward PP1 (IC50 131 μM) [117]. In addition to this selective inhibition, fostriecin also has the advantage of rapid action due to its higher water solubility, in contrast to more hydrophobic compounds such as okadaic acid and calyculin A which may take 24-48 hours before equilibrium is reached in cells [71]. Fostriecin exhibits potent cytotoxicity against a number of cancer cell lines and a strong antitumor effect in animals [118-120]. Apparently, inhibitors of PP2A can have pro-growth or pro-death properties depending on the concentration of the compounds. The properties of fostriecin that make it a better template for anticancer drug development over other toxins include both low toxicity and high selectivity [117, 121]. Fostriecin was entered into clinical trials sponsored by the National Cancer Institute to evaluate its antitumor activity in humans [122]. Although the trials were suspended due to the concerns about the storage stability of the naturally produced material, this discovery ignited a broad interest in derivatives of fostriecin. The complex structure of PP2A and fostriecin has not been determined, but detailed structure-activity relationship studies provide detailed information for elucidating the inhibitory mechanism [24]. In one study, more than 10 natural derivatives of fostriecin, which share a distinctive phosphate monoester and α, β-unsaturated δ-lactone structural units with fostriecin, were synthesized, and their inhibitory activities for PP1, PP2A and PP5 were examined [24]. This led to the identification of several key structural units of fostriecin that confer the high selectivity and strong inhibitory activity toward PP2A. While the C9-phosphate and C11-hydroxyl groups of fostriecin interact with the catalytic metals and conserved active site residues which are common to PPPs (specifically, PP1, PP2A and PP5), the unsaturated lactone contributes to the stronger inhibition toward PP2A by providing an electrophilic interaction with Cys269 in PP2A contained in the loop connecting β12-β13 [24].

One dilemma that has been puzzling: how can PP2A be the target for both the tumor-inducing agent okadaic acid and the anti-cancer compound fostriecin? Actually, toxin inhibitors for PP1 and PP2A, such as the tumor promoters okadaic acid and microcystins, are reported to have a dose-dependent dualistic response effect between apoptosis and cell proliferation [123]. Low doses of toxins promote cell proliferation by activating kinases that induce cell division such as MAPK and accelerate cell cycle progression [124]. In contrast, high doses of toxin induce cell death via a block of the cell cycle at G1/S and fragmentation of nuclei [125, 126]. Furthermore, the high concentration of toxins might also affect activity of other unknown low affinity targets. The cellular effects induced by various toxins are thus dosage-dependent, making therapeutic indices crucial for each compound.

PP2B (PP3, calcineurin) inhibitors

PP2B is also called calcineurin due to its dependence on Ca2+ for activity and stimulation by calmodulin. The predominant form of calcineurin in cells is a heterodimeric complex consisting of a catalytic subunit (calcineurin A, CNA) and a Ca2+-binding regulatory subunit (calcineurin B, CNB). The CNA subunit contains an N-terminal phosphatase domain and a C-terminal CNB-binding helical domain followed by a Ca2+-calmodulin-binding motif and an auto-inhibitory element (Figure 7). The CNB subunit, a member of the EF-hand family of Ca2+-binding proteins, contains four Ca2+-binding loops and shares about 35% sequence identity to calmodulin. The primary sequences of both subunits and the heterodimeric quaternary structure are highly conserved from yeast to humans. Calcineurin plays an important role in various Ca2+-dependent biological processes, including cardiac hypertrophy, neurodevelopment, memory, immune responses and muscle development [127].

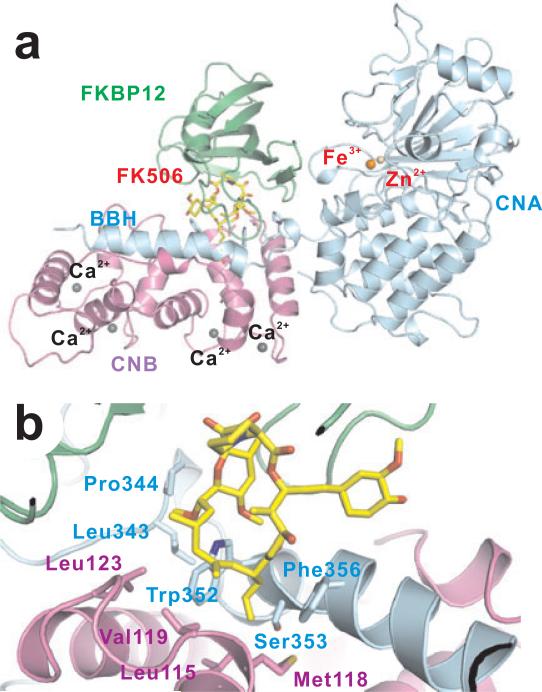

Figure 7. Complex structure of calcineurin bound to FKBP12-FK506.

(a) Overall structure of calcineurin heterodimer in complex with FKBP12-FK506 (PDB code: 1tco). Metal ions are indicated by spheres. (b) Zoom-in view of the FK506 binding site with the important surrounding residues shown in stick.

Calcineurin acquired a great deal of attention when it was identified as the cellular target for the immunosuppressants cyclosporine [128] and FK506 [129] (Figure 5, compound 7 and 8), which revolutionized organ transplantation [130]. Both compounds were discovered in soil samples (cyclosporine near the Arctic Circle in Norway and FK506 in the mountains of Japan). Interestingly, the immunosuppressants do not inhibit the activity of calcineurin themselves; instead, they exert their inhibitory activity by first binding to their corresponding protein partners called immunophilins to form immunophilin-immunosuppressant pairs, FKBP12-FK506 [131] and CyPA-CsA [132, 133]. The formation of this complex is believed to change the conformation of immunosuppressant and subsequently allow them to effectively bind calcineurin. To summarize, in the absence of the immunosuppressant FK506 or CsA, calcineurin will not directly bind to FKBP12 or CyPA; similarly, the complex of calcineurin and immunophilin will only form upon the association of the small molecule with immunophilin. This immunophilin-immunosuppressant-calcineurin complex effectively blocked the accessibility of calcineurin substrate to the active site of the phosphatase [134].

Complex structures of calcineurin bound with these two immunophilin-immunosuppressant pairs reveal the unique inhibition mechanism. The CNA and CNB subunits form an elbow-like overall structure with each subunit being an arm connected at the elbow joint (Figure 7a) [132, 133]. Both of the immunophilin-immunosuppressant pairs reside in the angle formed by the two arms, interacting with both subunits (Figure 7a). Interestingly, the major interaction between immunosuppressants and calcineurin lies in a hydrophobic cleft at the interface of CNB and BBH domain, which is a helix of the CNA subunit that is ~40 Å away from the phosphatase active site (Figure 7b). The remote location of immunosuppressant binding site raises the question: how the potent inhibition of calcineurin by immunosuppressants is achieved? Recently, by using a natural protein inhibitor (A238L) for calcineurin, it was possible to reveal the mechanism of the immunosuppressants. The complex between calcineurin and A238L showed that A238L binds to calcineurin in two calcineurin-specific substrate binding grooves, namely the PIxIxIT and LxVP substrate binding grooves [134]. Remarkably, the LxVP binding groove is precisely where the immunosuppressants bind to calcineurin. Thus, both the A238L viral protein inhibitor and the immunosuppressants effectively inhibit substrate binding [134].

The best-characterized substrates for calcineurin are the nuclear factors of activated T cells (NFATs) [135]. The dephosphorylation of NFATs by calcineurin is important for the translocation of NFATs into the nucleus, where they combine with other nuclear factors to activate the transcription of downstream genes that are essential for T-cell activation, such as interleukin-2 and interleukin-4 [136, 137]. The common inhibition mechanism of CsA and FK506 fulfills both requirements for high potency and selectivity while at the same time, providing a starting point to target the calcineurin-NFAT complex for better pharmacological properties and avoid the unwelcomed side effects of neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity caused by FK506 or CsA [138, 139]. Though the discovery of these popular immunosuppressants is primarily a story of serendipity, scientists can retrospectively investigate their mechanism and implement similar strategies to uncover other promising pharmaceuticals. Extensive medicinal chemistry efforts have been devoted to the synthesis of FK506 analogs to identify compounds with an improved therapeutic index, which could have broader therapeutic utility than the parent drugs. Specific inhibition of calcineurin activity toward NFAT can be achieved by directly blocking their association with small molecules. In a pilot study, Roehrl et al. identified several compounds, termed inhibitors of NFAT-calcineurin association (INCAs), by screening of a compound library containing 16,000 compounds [140]. The INCAs bind directly to calcineurin at the NFAT-binding site and thus prevent NFAT activation and subsequent cytokine expressions in T cells. Although the detailed mechanism of INCA-mediated inhibition of calcineurin is still unknown, the concept of disrupting the calcineurin-NFAT association has been proven plausible and such studies have paved the way for further development of novel immunosuppressive drugs [141].

PP5 as a drug target

Among the novel PPP subfamilies, PP5 has attracted attention as a potential drug target [142]. First, depleting PP5 was shown to induce G1 arrest in A549 lung carcinoma cells [143], indicating the potential of PP5 selective inhibitors to arrest the growth of cancerous cells. Second, PP5 is a single subunit protein with a canonical PPP catalytic domain fused with an N-terminal tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain, which is distinct from other PPP members. Third, PP5 has a limited pool of substrates; and therefore, the result of its inactivation is not as widespread as inactivation of PP1 or PP2A.

Due to the high conservation of the catalytic subunit of PP5 relative to PP1, PP2, PP4 and PP6, the natural toxins that abolish PP5 activity can also effectively inactivate the other PPPs. Therefore, even though much interest has been raised for the potential of PP5 as an anti-cancer target due to its role in p53-mediated DNA damage control [144], the requirement of selectivity will be a tall order to fulfill for PP5 inhibitors. One strategy would involve using high throughput assays to identify novel chemical compounds as initial hits but using PP1 and PP2A as the controls in a secondary assay to eliminate those hits lacking specificity.

Another interesting aspect about PP5-mediated signal transduction arise from its association with heat shock protein Hsp90 [145]. Similar to protein kinase A, PP5 auto-inhibits itself by using a TPR domain to block the access of substrate. Conformational changes induced by binding of TPR to Hsp90 or fatty acid therefore enhance the phosphatase activity of PP5 by allosteric activation of the enzyme [146].

The process of rational inhibitor design

Phosphatases have traditionally been viewed as ‘non-druggable targets’ that are not amenable to conventional, small-molecule therapeutics. There are several reasons for this reputation, which has hampered the development of PSP inhibitors. Pharmaceutical professionals have two major concerns. First, a huge number of phosphatases play essential roles in cellular function and any inhibition or even cross-inhibition by low-affinity inhibitors can result in devastating effects on the health of the organism. This leads to the second hurdle: the challenge of selectivity. This is reminiscent of the sentiment surrounding the kinase field ~20 years ago. Prior to the discovery of Gleevec, kinases were thought to be non-druggable targets. This was due to the highly conserved active site and similarity of the three-dimensional structures, a problem also faced by phosphatases. Now, however, kinase inhibitors have become one of the major classes of drugs used to treat cancer with dozens of kinase inhibitors in the pipeline of drug discovery for various diseases.

Kinases were brought into the limelight as major drug targets thanks to smart target selection and the utilization of a combination of modern technologies. Similar methodologies can be applied to phosphatases. For instance, only phosphatases that play unique roles in pathological pathways and whose activity is dispensable in the normal environment should be considered targets for drug discovery. The implementation of genomic approaches makes the identification and characterization of these phosphatases much faster than previously possible, allowing scientist to discern targets with greater reliability.

For the process of rationale inhibitor design, diversified strategies have been explored to effectively and selectively inactivate different phosphatases in order to understand their biological functions and eventually achieve therapeutic benefits. For the single subunit phosphatases such as Fcp/Scp, PPM and PP5, the structural elements that determine the selectivity toward substrates are localized close to the active site. Therefore, it is possible to identify small molecule compounds that display unique substrate characteristics and block the reaction. In this scenario, modern technology for targeted-drug discovery is a very powerful tool to identify initial leads from chemical libraries, followed by structure-aided inhibitor design and molecular docking to guide the optimization process, so identified compounds can be improved for potency and pharmaco-properties.

Because of the highly conserved active sites that exist in most of the PPP proteins, selectivity is determined remotely from the active site. Therefore, inactivating all forms of a targeted phosphatase subtype using a catalytic subunit inhibitor may lead to devastating toxic side effects since a large group of active holoenzymes will be inhibited. Selective inactivation needs to be enforced at the holoenzyme level rather than at the catalytic site itself. It is a challenge to design inhibitors that prevent the assembly of protein complexes and disrupt protein-protein interaction interfaces at the same time. In this case, scientists utilize natural products as the starting template for effective inhibition. The emerging wealth of structural data for phosphatases in complex with toxins facilitated the development of PSP inhibitors. The best and most successful example for inhibition of PPP proteins are FK506 and CsA which, when forming a complex with immunophilins, become highly potent and selective against calcineurin, making organ transplantation feasible. Using natural compounds as the starting point for focused library screening, compounds that favor certain holoenzymes are being evaluated for effects on cellular functions and optimized to treat diseases such as cancer.

In addition to direct modulating a phosphatase, another approach can target regulatory subunits of holoenzyme complexes. Even though it is not the focus of our discussion in this review, a successful case of activating tumor suppressor PP2A by inhibiting its inhibitor protein has indicated that such a strategy can be highly effective in medical application.

Phosphatases present a huge challenge to drug discovery efforts; however, the pay-off for the ability to control phosphatase activity is tremendous. Nature has developed a multitude of strategies to effectively modulate phosphatase activity providing scientists with a wealth of initial leads, all capable of pushing us towards successfully harnessing this potential. By utilizing nature as our guide and technological advances as a means of inquiry, small molecule inhibitors are designed to study phosphatases and treat human diseases.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. H. Yu for her comment on the manuscript. The work of PI was supported by Welch Foundation Grant (F-1778 to Y. Z.), NIH (R03DA030556 to Y.Z.), Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation (20120802 to Y. Z), and Powers Graduate Fellowship (M.Z).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Gunawardena J. Multisite protein phosphorylation makes a good threshold but can be a poor switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14617–14622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507322102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagaraj N, Wisniewski JR, Geiger T, Cox J, Kircher M, Kelso J, Paabo S, Mann M. Deep proteome and transcriptome mapping of a human cancer cell line. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:548. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunter T. Protein kinases and phosphatases: the yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signaling. Cell. 1995;80:225–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novak B, Kapuy O, Domingo-Sananes MR, Tyson JJ. Regulated protein kinases and phosphatases in cell cycle decisions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:801–808. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Munter S, Kohn M, Bollen M. Challenges and opportunities in the development of protein phosphatase-directed therapeutics. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:36–45. doi: 10.1021/cb300597g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen P. Protein kinases--the major drug targets of the twenty-first century? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:309–315. doi: 10.1038/nrd773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondapalli L, Soltani K, Lacouture ME. The promise of molecular targeted therapies: protein kinase inhibitors in the treatment of cutaneous malignancies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant SK. Therapeutic protein kinase inhibitors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1163–1177. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8539-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, Mann M. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen P. Signal integration at the level of protein kinases, protein phosphatases and their substrates. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17:408–413. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayer-Jaekel RE, Hemmings BA. Protein phosphatase 2A--a 'menage a trois'. Trends Cell Biol. 1994;4:287–291. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(94)90219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wurzenberger C, Gerlich DW. Phosphatases: providing safe passage through mitotic exit. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:469–482. doi: 10.1038/nrm3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson ES, Kornbluth S. Phosphatases driving mitosis: pushing the gas and lifting the brakes. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2012;106:327–341. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396456-4.00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mochida S, Hunt T. Protein phosphatases and their regulation in the control of mitosis. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:197–203. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ceulemans H, Bollen M. Functional diversity of protein phosphatase-1, a cellular economizer and reset button. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1–39. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamenski T, Heilmeier S, Meinhart A, Cramer P. Structure and mechanism of RNA polymerase II CTD phosphatases. Mol Cell. 2004;15:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallego M, Virshup DM. Protein serine/threonine phosphatases: life, death, and sleeping. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alonso A, Sasin J, Bottini N, Friedberg I, Osterman A, Godzik A, Hunter T, Dixon J, Mustelin T. Protein tyrosine phosphatases in the human genome. Cell. 2004;117:699–711. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yap TA, Workman P. Exploiting the cancer genome: strategies for the discovery and clinical development of targeted molecular therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:549–573. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi Y. Serine/threonine phosphatases: mechanism through structure. Cell. 2009;139:468–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das AK, Helps NR, Cohen PT, Barford D. Crystal structure of the protein serine/threonine phosphatase 2C at 2.0 A resolution. Embo J. 1996;15:6798–6809. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belova GI, Demidov ON, Fornace AJ, Jr, Bulavin DV. Chemical inhibition of Wip1 phosphatase contributes to suppression of tumorigenesis. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:1154–1158. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.10.2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaguchi H, Durell SR, Feng H, Bai Y, Anderson CW, Appella E. Development of a substrate-based cyclic phosphopeptide inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2Cdelta, Wip1. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13193–13202. doi: 10.1021/bi061356b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swingle MR, Amable L, Lawhorn BG, Buck SB, Burke CP, Ratti P, Fischer KL, Boger DL, Honkanen RE. Structure-activity relationship studies of fostriecin, cytostatin, and key analogs, with PP1, PP2A, PP5, and( beta12-beta13)-chimeras (PP1/PP2A and PP5/PP2A), provide further insight into the inhibitory actions of fostriecin family inhibitors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:45–53. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.155630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He R, Zeng LF, He Y, Zhang S, Zhang ZY. Small molecule tools for functional interrogation of protein tyrosine phosphatases. Febs J. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08718.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen KN, Dunaway-Mariano D. Phosphoryl group transfer: evolution of a catalytic scaffold. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang M, Liu J, Kim Y, Dixon JE, Pfaff SL, Gill GN, Noel JP, Zhang Y. Structural and functional analysis of the phosphoryl transfer reaction mediated by the human small C-terminal domain phosphatase, Scp1. Protein Sci. 2010;19:974–986. doi: 10.1002/pro.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egloff S, Murphy S. Cracking the RNA polymerase II CTD code. Trends Genet. 2008;24:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Archambault J, Chambers RS, Kobor MS, Ho Y, Cartier M, Bolotin D, Andrews B, Kane CM, Greenblatt J. An essential component of a C-terminal domain phosphatase that interacts with transcription factor IIF in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14300–14305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hausmann S, Koiwa H, Krishnamurthy S, Hampsey M, Shuman S. Different strategies for carboxyl-terminal domain (CTD) recognition by serine 5-specific CTD phosphatases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37681–37688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeo M, Lee SK, Lee B, Ruiz EC, Pfaff SL, Gill GN. Small CTD phosphatases function in silencing neuronal gene expression. Science. 2005;307:596–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1100801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Visvanathan J, Lee S, Lee B, Lee JW, Lee SK. The microRNA miR-124 antagonizes the anti-neural REST/SCP1 pathway during embryonic CNS development. Genes Dev. 2007;21:744–749. doi: 10.1101/gad.1519107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xue Y, Ouyang K, Huang J, Zhou Y, Ouyang H, Li H, Wang G, Wu Q, Wei C, Bi Y, Jiang L, Cai Z, Sun H, Zhang K, Zhang Y, Chen J, Fu XD. Direct conversion of fibroblasts to neurons by reprogramming PTB-regulated microRNA circuits. Cell. 2013;152:82–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho EJ, Kobor MS, Kim M, Greenblatt J, Buratowski S. Opposing effects of Ctk1 kinase and Fcp1 phosphatase at Ser 2 of the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3319–3329. doi: 10.1101/gad.935901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hausmann S, Shuman S. Characterization of the CTD phosphatase Fcp1 from fission yeast. Preferential dephosphorylation of serine 2 versus serine 5. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21213–21220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeo M, Lin PS, Dahmus ME, Gill GN. A novel RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain phosphatase that preferentially dephosphorylates serine 5. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26078–26085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301791200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghosh A, Shuman S, Lima CD. The structure of Fcp1, an essential RNA polymerase II CTD phosphatase. Mol Cell. 2008;32:478–490. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Kim Y, Genoud N, Gao J, Kelly JW, Pfaff SL, Gill GN, Dixon JE, Noel JP. Determinants for dephosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain by Scp1. Mol Cell. 2006;24:759–770. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang M, Gill GN, Zhang Y. Bio-molecular architects: a scaffold provided by the C-terminal domain of eukaryotic RNA polymerase II. Nano Rev. 2010;1 doi: 10.3402/nano.v1i0.5502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang M, Cho EJ, Burstein G, Siegel D, Zhang Y. Selective inactivation of a human neuronal silencing phosphatase by a small molecule inhibitor. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:511–519. doi: 10.1021/cb100357t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sapkota G, Knockaert M, Alarcon C, Montalvo E, Brivanlou AH, Massague J. Dephosphorylation of the linker regions of Smad1 and Smad2/3 by small C-terminal domain phosphatases has distinct outcomes for bone morphogenetic protein and transforming growth factor-beta pathways. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:40412–40419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dai J, Zhang J, Sun Y, Wu Q, Sun L, Ji C, Gu S, Feng C, Xie Y, Mao Y. Characterization of a novel human protein phosphatase 2C family member, PP2Ckappa. Int J Mol Med. 2006;17:1117–1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu X, Bocangel D, Nannenga B, Yamaguchi H, Appella E, Donehower LA. The p53-induced oncogenic phosphatase PPM1D interacts with uracil DNA glycosylase and suppresses base excision repair. Mol Cell. 2004;15:621–634. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shreeram S, Demidov ON, Hee WK, Yamaguchi H, Onishi N, Kek C, Timofeev ON, Dudgeon C, Fornace AJ, Anderson CW, Minami Y, Appella E, Bulavin DV. Wip1 phosphatase modulates ATM-dependent signaling pathways. Mol Cell. 2006;23:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lammers T, Peschke P, Ehemann V, Debus J, Slobodin B, Lavi S, Huber P. Role of PP2Calpha in cell growth, in radio- and chemosensitivity, and in tumorigenicity. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:65. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen M, Pratt CP, Zeeman ME, Schultz N, Taylor BS, O'Neill A, Castillo-Martin M, Nowak DG, Naguib A, Grace DM, Murn J, Navin N, Atwal GS, Sander C, Gerald WL, Cordon-Cardo C, Newton AC, Carver BS, Trotman LC. Identification of PHLPP1 as a tumor suppressor reveals the role of feedback activation in PTEN-mutant prostate cancer progression. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:173–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warfel NA, Newton AC. Pleckstrin homology domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase (PHLPP): a new player in cell signaling. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:3610–3616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.318675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu X, Nguyen TA, Moon SH, Darlington Y, Sommer M, Donehower LA. The type 2C phosphatase Wip1: an oncogenic regulator of tumor suppressor and DNA damage response pathways. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:123–135. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9127-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bulavin DV, Demidov ON, Saito S, Kauraniemi P, Phillips C, Amundson SA, Ambrosino C, Sauter G, Nebreda AR, Anderson CW, Kallioniemi A, Fornace AJ, Jr., Appella E. Amplification of PPM1D in human tumors abrogates p53 tumor-suppressor activity. Nat Genet. 2002;31:210–215. doi: 10.1038/ng894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li J, Yang Y, Peng Y, Austin RJ, van Eyndhoven WG, Nguyen KC, Gabriele T, McCurrach ME, Marks JR, Hoey T, Lowe SW, Powers S. Oncogenic properties of PPM1D located within a breast cancer amplification epicenter at 17q23. Nat Genet. 2002;31:133–134. doi: 10.1038/ng888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Castellino RC, De Bortoli M, Lu X, Moon SH, Nguyen TA, Shepard MA, Rao PH, Donehower LA, Kim JY. Medulloblastomas overexpress the p53-inactivating oncogene WIP1/PPM1D. J Neurooncol. 2008;86:245–256. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9470-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tan DS, Lambros MB, Rayter S, Natrajan R, Vatcheva R, Gao Q, Marchio C, Geyer FC, Savage K, Parry S, Fenwick K, Tamber N, Mackay A, Dexter T, Jameson C, McCluggage WG, Williams A, Graham A, Faratian D, El-Bahrawy M, Paige AJ, Gabra H, Gore ME, Zvelebil M, Lord CJ, Kaye SB, Ashworth A, Reis-Filho JS. PPM1D is a potential therapeutic target in ovarian clear cell carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2269–2280. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saito-Ohara F, Imoto I, Inoue J, Hosoi H, Nakagawara A, Sugimoto T, Inazawa J. PPM1D is a potential target for 17q gain in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1876–1883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Le Guezennec X, Bulavin DV. WIP1 phosphatase at the crossroads of cancer and aging. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bulavin DV, Phillips C, Nannenga B, Timofeev O, Donehower LA, Anderson CW, Appella E, Fornace AJ., Jr. Inactivation of the Wip1 phosphatase inhibits mammary tumorigenesis through p38 MAPK-mediated activation of the p16(Ink4a)-p19(Arf) pathway. Nat Genet. 2004;36:343–350. doi: 10.1038/ng1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu X, Ma O, Nguyen TA, Jones SN, Oren M, Donehower LA. The Wip1 Phosphatase acts as a gatekeeper in the p53-Mdm2 autoregulatory loop. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:342–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takekawa M, Adachi M, Nakahata A, Nakayama I, Itoh F, Tsukuda H, Taya Y, Imai K. p53-inducible wip1 phosphatase mediates a negative feedback regulation of p38 MAPK-p53 signaling in response to UV radiation. Embo J. 2000;19:6517–6526. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vogt A, Tamewitz A, Skoko J, Sikorski RP, Giuliano KA, Lazo JS. The benzo[c]phenanthridine alkaloid, sanguinarine, is a selective, cell-active inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19078–19086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rogers JP, Beuscher AEt, Flajolet M, McAvoy T, Nairn AC, Olson AJ, Greengard P. Discovery of protein phosphatase 2C inhibitors by virtual screening. J Med Chem. 2006;49:1658–1667. doi: 10.1021/jm051033y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O'Neill AK, Niederst MJ, Newton AC. Suppression of survival signalling pathways by the phosphatase PHLPP. Febs J. 2013;280:572–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sierecki E, Sinko W, McCammon JA, Newton AC. Discovery of small molecule inhibitors of the PH domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase (PHLPP) by chemical and virtual screening. J Med Chem. 2010;53:6899–6911. doi: 10.1021/jm100331d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aburai N, Yoshida M, Ohnishi M, Kimura K. Sanguinarine as a potent and specific inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2C in vitro and induces apoptosis via phosphorylation of p38 in HL60 cells. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2010;74:548–552. doi: 10.1271/bbb.90735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Swierczek K, Pandey AS, Peters JW, Hengge AC. A comparison of phosphonothioic acids with phosphonic acids as phosphatase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2003;46:3703–3708. doi: 10.1021/jm030106f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lin YX, Xu WN, Liang LR, Pang BS, Nie XH, Zhang J, Wang H, Liu YX, Wang DQ, Xu ZY, Wang HW, Zhang HS, He ZY, Yang T, Wang C. The cross-sectional and longitudinal association of the BODE index with quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chin Med J (Engl) 2009;122:2939–2944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goldberg J, Huang HB, Kwon YG, Greengard P, Nairn AC, Kuriyan J. Three-dimensional structure of the catalytic subunit of protein serine/threonine phosphatase-1. Nature. 1995;376:745–753. doi: 10.1038/376745a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Egloff MP, Cohen PT, Reinemer P, Barford D. Crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of human protein phosphatase 1 and its complex with tungstate. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:942–959. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tachibana K, Scheuer PJ, Tsukitani Y, Kikushi H, Engen DV, Clardy J, Gopichand Y, Schmitz FJ. Okadaic acid, a cytotoxic polyether from the marine sponges of the genus Halichondria. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:2469–2471. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bialojan C, Takai A. Inhibitory effect of a marine-sponge toxin, okadaic acid, on protein phosphatases. Specificity and kinetics. Biochem J. 1988;256:283–290. doi: 10.1042/bj2560283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.MacKintosh C, Beattie KA, Klumpp S, Cohen P, Codd GA. Cyanobacterial microcystin-LR is a potent and specific inhibitor of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A from both mammals and higher plants. FEBS Lett. 1990;264:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80245-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]