Abstract

Economic hardship and poor parenting behaviors are associated with increased risk for mental health problems in community adolescents. However, less is known about the impact of socioeconomic status (SES) and parenting behaviors on youth at elevated risk for mental health problems, such as teens seeking outpatient psychiatric care. This study examined whether family SES and parent positive communication were directly and indirectly associated with mental health symptoms six months later in urban teens seeking outpatient treatment, after accounting for baseline levels of symptoms. At baseline, adolescent participants (N = 346; 42% female; 61% African-American) ages 12 to 19 years old (M = 14.9; SD = 1.8) and their primary caregivers reported on SES and teen internalizing and externalizing symptoms and engaged in a videotaped discussion of a real-life conflict to assess parent positive communication. At 6-month follow-up, 81% (N = 279) of families were retained and teens and caregivers again reported internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to test the hypothesized models with a sample of 338, using the full information likelihood method to adjust for missing data. For parent-reported externalizing symptoms, SEM revealed support for the indirect association of SES with follow-up externalizing symptoms via parent positive communication and externalizing symptoms at baseline. For parent reported internalizing symptoms, there was a direct association between SES and follow-up internalizing symptoms, but not an indirect effect via parent positive communication. Youth-reported symptoms were not associated with SES nor with parent positive communication. Current findings extend prior research on adolescent mental health in a diverse sample of urban youth seeking outpatient psychiatric care. These families may benefit from interventions that directly target SES-related difficulties and parent positive communication.

Keywords: adolescent, urban, mental health, SES, parent-adolescent communication

Introduction

Adolescence is a period of increased risk for internalizing and externalizing disorders, including depression, social anxiety and panic disorders, disruptive behavior disorders, and substance abuse (Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003; Kessler, Avenevoli, & Merikangas, 2001). Epidemiological studies estimate that one-third to one-fourth of adolescents have a lifetime prevalence of psychological disorder with functional impairment (Merikangas, Nakamura, & Kessler, 2009; Merikangas et al., 2010), and disorders that start in adolescence are often a source of disability throughout adulthood (Costello, Egger, & Angold, 2005). Economic hardship increases the risk for adolescent psychopathology through several pathways, including disruptions in the parent-adolescent relationship (e.g., Barrera et al., 2002; Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz, & Simons, 1994; Conger, Wallace, Sun, Simons, McLoyd, & Brody, 2002; Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Grant et al., 2003), but prior research has mainly focused on community samples.

Economic stressors exacerbate mental health problems in children and adolescents. Economic hardship impacts youth mental health through multiple pathways, including neighborhood quality (e.g., community violence), home environment (e.g., crowding), limited access to resources, physical health problems, parental psychopathology, and maladaptive family processes (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Leung & Shek, 2011; McLoyd, 2011). The family stress model focuses on the pathway from economic hardship to youth mental health via parental and family processes (Conger & Conger, 2002). Specifically, the model proposes that economic stress and strain may cause parental emotional distress and marital conflict, which leads to disrupted parenting; in turn, negative parental behaviors lead to youth adjustment problems. The family stress model has been well-validated in multiple populations of community youth, including low-income rural Euro-American (Conger & Conger, 2002) and African-American youth (Conger et al., 2002). Further, a meta-analytic review of 43 studies examining the family stress model (Grant et al., 2003) concluded that economic hardship has a direct effect on adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems, although longitudinal findings indicated that the effect was almost three times larger for externalizing than internalizing symptoms. Additionally, the authors found an indirect effect on symptoms through poor parenting (i.e., high hostility and low support; Grant et al., 2003).

Research on the family stress model would benefit from extension to a low-income, urban, treatment-seeking sample. It is crucial to replicate and extend research with representative samples in order to develop tailored interventions for high-risk youth (La Greca, Silverman & Lochman, 2009). The vast majority of studies using the family stress model have examined community samples, but it is possible that low-income, urban, treatment-seeking adolescents face stressors that override the role of parent-adolescent relationships. In particular, low-income, urban, treatment-seeking youth are often faced with poor neighborhood quality, crowding, and exposure to community violence, which may account for the effect of SES on mental health in this population (Katz, Esparza, Carter, Grant, & Meyerson, 2012) moreso than parenting. Thus, testing the family stress model with this population can provide valuable information about the relative importance of involving caregivers in treatment, even in families with low resources and roadblocks to treatment utilization. If parental behaviors are not significantly related to youth mental health, or do not account for the relationship between SES and mental health, then treatment may benefit from placing less emphasis on parental involvement, especially if their involvement results in time lost for other activities (e.g., work) and financial strain for the family.

Research on the family stress model would also benefit from examining parent-adolescent communication as an aspect of parent-adolescent relationships. Parent positive communication, such as talking openly and frequently, providing clear information, listening, and being responsive, is related to lower adolescent risk behaviors, including alcohol, tobacco and drug use and sexual risk behaviors (Blake et al., 2000; DiClemente et al., 2001; Donenberg et al., 2011; Litrownik et al., 2000). Parent positive communication, including parents’ ability to provide clear information and listen responsively to their teens, may be associated with, but somewhat independent from, other positive parenting behaviors such as warmth or nurturance, which are typically studied in the family stress model. Parent positive communication may be a protective factor in the mental health of youth seeking treatment, and communication skills are more tangible and teachable than broader behaviors such as warmth. Hence, examining parent communication has specific implications for treatment, as parental communication skills can be targeted in family-based interventions.

Additionally, recent findings suggest reciprocal relationships between parental behavior and youth mental health (Bradley & Corwyn, 2013; Roche, Ghazarian, Little, & Leventhal, 2011; Wang, Dishion, Stormshak, & Willett, 2011; Williams & Steinberg, 2011). The strength and reciprocity of these relationships may be more relevant to treatment-seeking youth compared with community youth. When youths’ mental health problems are severe enough that families seek treatment, these problems have likely resulted in disruptions or changes to parenting behaviors (e.g., Bradley & Corwyn, 2013; Wang et al., 2011). For example, youth with externalizing problems may be expelled from school or become involved in the juvenile justice system, while youth with internalizing problems may require additional caretaking or parental advocacy for school accommodations. As a result, parents may experience elevated parenting stress and psychopathology, and struggle to communicate, even if they have positive communication skills in less stressful situations. Given the potential for this strong reciprocal relationship, it is important to examine the family stress model in treatment-seeking populations to determine if interventions should initially aim to reduce youth symptoms through parenting or through other means.

Finally, studies of the family stress model have typically relied on a single reporter, or combined youth- and parent-reports of symptoms into one construct (e.g., Brody & Ge, 2001; Conger et al., 1994; Conger et al., 2002). However, associations between parent and child reports of children's behavior are typically small (Achenbach, McConaughy & Howell, 1987), suggesting that relationships may differ by reporter. Further, it is important to distinguish outcomes from parent and youth reporters, because informant discrepancies are tied to important differences in perception and attributions of behaviors (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). For example, parents are more likely to attribute youth behavior to disposition, while youth are more likely to attribute their behavior to environment, which has implications for treatment (e.g., helping parents to consider alternative explanations for youth behavior besides disposition). Given reciprocal relationships between parental behavior and youth mental health symptoms, parental observations of youth symptoms (compared to youth self-reports) may have the greatest influence on parental behaviors such as positive communication. Therefore, more research is needed examining child and parent reports separately, with consideration to differences in informant attributions and perceptions.

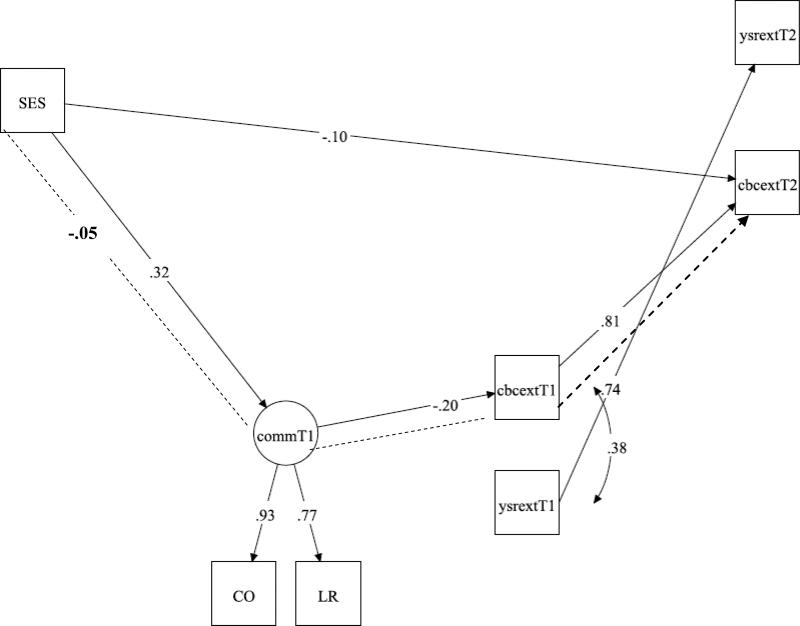

This study extends research on adolescent mental health in several ways. First, we applied a theoretical framework based on the family stress model to understand the direct and indirect associations between SES, parent behavior, and adolescent mental health in primarily low-income, racially diverse, urban families seeking outpatient treatment for their teens (see Figure 1). Second, we examined a potentially critical protective factor, parent positive communication, as a variable that could partly account for the association between SES and adolescent mental health at follow-up. Third, we examined parent- and youth-reports of youth symptoms separately, rather than relying on only one reporter or combining reports.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the relationships between SES, parent positive communication, and adolescent mental health symptoms. Note. Solid lines represent direct associations; dotted lines represent indirect associations. Only direct associations were hypothesized to be statistically significant in the current study. T1 = baseline. T2 = 6-month follow-up. CO = Communication; LR = Listener Responsiveness.

Similar to findings with the family stress model in community samples (Grant et al., 2003), we hypothesized that SES would be positively associated with parent positive communication at baseline. We expected this association even in a treatment-seeking sample because there are factors separate from youth problems (e.g., parental stress and psychopathology) that mitigate the relationship between SES and parental behaviors (Conger & Conger, 2002). We also expected baseline SES to be directly negatively associated with teen symptoms at baseline and follow-up, due to the multiple pathways by which SES would be linked to both internalizing and externalizing symptoms in low-income, urban, treatment-seeking youth (e.g., poor neighborhood quality, exposure to community violence, lack of resources for health promotion).

Also consistent with the family stress model, we predicted a small but significant negative association between baseline parent positive communication and symptoms at baseline and follow-up. We expected to find an association given previous findings that there are reciprocal relationships between parent behaviors and youth symptoms, particularly in youth with functionally impairing symptoms (e.g., Williams & Steinberg, 2011). We also expected that parent positive communication would account for a significant amount of the relationship between SES and youth problems at follow-up in the current study. However, we expected that this effect might be smaller than what is typically found in community samples, because other SES-related factors unmeasured in this study (e.g., community violence exposure) likely play a larger role in the relationship between SES and later symptoms in a low-income, urban sample of youth with functionally disruptive symptoms at baseline. Finally, expanding on the family stress model, we hypothesized that SES and parent positive communication would be more strongly associated with parent reports of youth symptoms, compared to youth self-reports, because parental behaviors are more likely to be associated with their own perceptions of youth problems.

Method

Participants

At baseline, participants were 346 adolescents and their primary caregivers who provided questionnaire data. Eighty-six percent (N = 299) of these dyads also completed a videotaped interaction at baseline. Eighty-one percent (N = 279) of the families were retained at 6-month follow up. There were no statistically significant differences in age, gender, or race/ethnicity between the baseline and 6-month follow-up samples. We used the full information likelihood method to adjust for missing data, resulting in a sample of 338 for the SEM analyses. The full information likelihood method calculates a likelihood function (the weighted least square parameter estimates) for missing data using all data available for each case and therefore avoids loss of power (Allison, 2003; Schlomer, Bauman & Card, 2010). Thus, we utilized the majority of baseline cases (98%) for the SEM analyses.

At baseline, youths ranged in age from 12 to 19 (M = 14.9; SD = 1.8) and 42% (N = 145) were female. Adolescents were racially and ethnically diverse: 61% (N = 210) African American, 19% (N = 67) White; 13% (N = 46) Latino, 4% (N = 13) Biracial; 3% (N = 10) of another race/ethnicity. Participants qualified for a range of psychiatric disorders based on the Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (CDISC; Shaffer, Fisher, Piacentini, Schwab-Stone, & Wiks, 1991). According to youths’ report, 10% (N = 35) met criteria for a mood disorder, 20% (N = 68) met criteria for an anxiety disorder, 12% (N = 43) met criteria for conduct disorder, and 30% (N = 105) met criteria for at least one disorder. According to parents’ report, 16% (N = 56) of the teens met criteria for a mood disorder, 20% (N = 69) met criteria for an anxiety disorder, 26% (N = 84) met criteria for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, 27% (N = 89) met criteria for oppositional defiant disorder, 15% (N = 49) met criteria for conduct disorder, and 55% (N = 192) met criteria for at least one disorder. Overall, 70% (N = 229) of youth met symptom criteria for any diagnosis when endorsed by either parent or child, while 21% (N = 67) of youth met criteria for any diagnosis when endorsed by both parent and child. At 6 months, 55% (N = 154) of the sample was still receiving outpatient treatment for mental health services, and from baseline to 6 months, 8% (N = 21) had been hospitalized for psychiatric reasons. Fifty-eight percent (N = 196) of the families scored in the first three levels of the Hollingshead (1975) index, indicating low to lower-middle incomes. Approximately 90% of caregivers (hereafter referred to as “parents”) were female and 72% were biological mothers.

All youth in the sample were included in this study, even if they did not reach assessment cutoffs for clinical level problems. Treatment seeking likely indicates significant functional impairment, especially in a lower-income, urban, minority population where unmet mental health needs are higher than the general population (e.g., Kataoka, Zhang & Wells, 2002). Thus, even those youth who did not meet clinical cutoffs are different from community youth, since their treatment seeking behavior indicates their problems have reached a level of impairment that brought them to treatment. Thus, we chose to include the full sample, as representative of youth who experience functional impairment due to mental health problems.

Procedure

Data are from a larger longitudinal study to understand HIV-risk behavior among youth seeking outpatient psychiatric care. This paper includes youth who participated in the first and second waves of data collection. Details regarding baseline recruitment methods and consent rates are provided elsewhere (Donenberg et al., 2005). Briefly, adolescents and their primary caregivers were recruited from four outpatient psychiatric clinics in Chicago. At baseline, all adolescents had received, at minimum, the outpatient clinic intake procedure. At baseline and six-month follow up, caregivers and youths separately completed self-report measures and interviews, and they participated in a 30-minute videotaped interaction that consisted of three tasks: a 5-minute warm-up, a 15-minute discussion of several health-related scenarios, and a 10-minute real-life conflict discussion. The current study uses data from the conflict discussion task. The Potential Parent-Child Problems (PPCP; Donenberg & Weisz, 1997) was used to identify a topic for the conflict discussion. Caregivers and adolescents independently rated how much they disagreed about 14 issues (e.g., grades, chores, friends, curfew, privacy), and the item rated as most conflictual by both people and least discrepant between them was used to generate the conflict discussion. Caregivers and adolescents were instructed to spend ten minutes discussing and resolving the issue identified by the PPCP. Study procedures were approved by all affiliated Institutional Review Boards, youth and caregivers provided informed consent or assent, and participants were compensated for their participation.

Measures

Adolescent demographics

Parents reported adolescent's age, gender, race, and ethnicity.

Socioeconomic status

Family socioeconomic status (SES) was assessed using the Hollingshead Index (Hollingshead, 1975). To calculate SES, parents reported on the occupation and education of up to two family members who contributed to finances in the home. Scores ranged from 1 to 5 with higher values representing higher levels of SES.

Adolescent mental health symptoms

In this study, symptoms were assessed by the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Both measures show excellent internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and construct validity across gender and race/ethnicity in previous research. The Internalizing Problems and Externalizing Problems T-scores were used as primary measures of mental health symptoms in the current study. The Internalizing Problems subscale includes anxiety and depression symptoms as well as somatic complaints (e.g., headaches, stomachaches). The Externalizing Problems subscale includes rule-breaking, lying, and aggression.

Parent Positive Communication

The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (IFIRS; Melby & Conger, 2001) was used to code verbal and non-verbal parent behavior during the parent-teen conflict discussion. Codes were assigned a value from 1 (behavior or emotion did not occur) to 5 (behavior or emotion is “mainly characteristic” of the parent). Both the frequency and intensity of the parent behavior were considered in rating each code. Two parent codes were included in the present analyses to capture parent positive communication: Communication and Listener Responsiveness. Communication was defined as the parent using reasoning, explanations and clarifications to convey ideas in a positive or neutral manner as well as to solicit the adolescent's point of view. Listener Responsiveness was defined as verbal or non-verbal behavior toward the adolescent that shows the parent is attending to, acknowledging, or validating what the adolescent says (e.g., eye contact, nodding, asking clarifying questions).

Prior to coding, a team of 10-12 individuals representing diverse racial, ethnic and educational backgrounds met and discussed the cultural relevance of the IFIRS for an urban, racially diverse population. Following initial training by the IFIRS’ developer (Jan Melby), coders met weekly over the next 12 months to add clarifications and examples to the manual to more accurately reflect family interactions in diverse urban families. Once the adaptations to the manual were finalized, raters were required to pass a written test of code definitions, clarifications, and examples, and they practiced coding videotapes. The coders continued to meet weekly with the research team to discuss questions and prevent criterion drift. Once the coders were consistently within one to two points of agreement on all scales, videotapes were rated by at least one person, with 30% (N = 91) coded by at least one additional rater for reliability. Videotapes coded for reliability were discussed by the raters and discrepancies were resolved through consensus. Final reliability assessment yielded intraclass correlations of .69 for Communication and .73 for Listener Responsiveness. A latent “parent positive communication” variable was created using these two scales, supported by the high bivariate correlation between these variables (r = .72 p < .001) and the high factor loadings (ranging from .77 to .93) for each of the factors on the latent variable in the various SEM analyses.

Data Analyses

Preliminary analyses examined descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among study variables. Subsequent analyses used Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) procedures and the statistical software MPLUS (Muthén & Muthén, 2001). In general, models with CFI values greater than .90 and RMSEA values less than .10 are considered adequate fits to the data (Hu & Bentler, 1999). We tested the structural model hypothesized in Figure 1 twice: once for internalizing symptoms and once for externalizing symptoms. Parent and child reports of symptoms were included in the same models. We initially controlled for youth age in the full models, but age was not significantly associated with any variables, and thus, final analyses did not control for age. Preliminary analyses comparing models for boys and girls suggested that model fits did not differ by gender; therefore, we did not constrain models by gender in the final analyses. As displayed in Figure 1, we tested the full models examining the effects of SES and parent positive communication on follow-up symptoms while accounting for baseline symptoms.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among study variables at baseline and 6-month follow-up. Descriptive analyses further indicated that the sample represented youth with above average levels of mental health problems. Mean T-scores on the Youth Self-Report and Child Behavior Checklist (YSR and CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) at baseline indicated higher than average levels of internalizing problems (YSR M = 55.0, SD = 10.4; CBCL M = 62.2, SD = 11.3) and externalizing problems (YSR M = 56.9, SD = 10.9; CBCL M = 63.0, SD = 11.8). At 6 months, mean T-scores on the YSR and CBCL internalizing problems (YSR M = 50.3, SD = 10.3; CBCL M = 59.2, SD = 11.8) and externalizing problems (YSR M = 55.5, SD = 11.1; CBCL M = 61.3, SD = 12.6) remained slightly elevated, except for the YSR internalizing scale. The clinical cutoff for the Internalizing and Externalizing Problems scales is a T-score > 63, and nationally normed data indicate that 10 percent of youth have scores above this cutoff. Consistent with criteria established by Brown et al. (2010), at baseline 56% (N = 193) of youth met the clinical cutoff for internalizing problems based on parent (CBCL) or teen (YSR) reports, and 59% (N = 205) met the clinical cutoff for externalizing problems based on parent (CBCL) or teen (YSR) reports. At 6 months, 40% (N = 109) of youth met the clinical cutoff for internalizing problems based on parent (CBCL) or teen (YSR) reports, and 49% (N = 135) met the clinical cutoff for externalizing problems based on parent (CBCL) or teen (YSR) reports. These data suggest that youth were approximately four to six times more likely to suffer from clinically significant levels of internalizing and externalizing problems at baseline and at follow-up, compared to a national sample.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among study variables.

| Mean (SD) | IFIRS CO | IFIRS LR | SES | CBC Int T1 | YSR Int T1 | CBC Ext T1 | YSR Ext T1 | CBC Int T2 | YSR Int T2 | CBC Ext T2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFIRS CO | 4.0 (0.8) | ||||||||||

| IFIRS LR | 4.5 (0.7) | .72** | |||||||||

| SES | 3.0 (1.3) | .29** | .24** | ||||||||

| CBC Int T1 | 62.2 (11.3) | .01 | .03 | −.13* | |||||||

| YSR Int T1 | 55.0 (10.4) | .01 | .06 | .02 | .24** | ||||||

| CBC Ext T1 | 63.0 (11.8) | −.21** | −.18** | −.17** | .47** | .03 | |||||

| YSR Ext T1 | 56.9 (10.9) | −.09 | .01 | .01 | .11* | .46* | .38** | ||||

| CBC Int T2 | 59.2 (11.8) | .01 | .04 | −.17** | .73** | .31** | .38** | .16** | |||

| YSR Int T2 | 50.3 (10.3) | −.06 | .02 | −.03 | .27** | .70** | .03 | .33** | .34** | ||

| CBC Ext T2 | 61.3 (12.6) | −.23** | −.22 | −.23** | .37** | .07 | .83** | .38** | .52** | .09 | |

| YSR Ext T2 | 55.5 (11.1) | −.08 | .04 | −.07 | .11 | .34** | .41** | .74** | .11 | .46** | .38** |

Note. IFIRS = Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales. CO = Communication. LR = Listener Responsiveness. SES and parent communication are at baseline. Int = Internalizing. Ext = Externalizing. T1 = baseline. T2 = 6-month follow-up. YSR = Youth Self-Report. CBC = Child Behavior Checklist.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Correlational analyses indicated that SES was positively associated with parent positive communication variables. SES was negatively associated with parent report of internalizing and externalizing symptoms at baseline and 6 months, but not significantly associated with youth self-reported symptoms. Correlations of symptom reports between parent and youth informants were significant and small to moderate, while within informant correlations from baseline to 6 months were significant and moderate to large (see Table 1).

SEM analyses: Testing the Fit of the Model for Internalizing Symptoms

The data fit the full model well (χ2 = 11.49 (6), p = .07; RMSEA =.05, CI=0.00 to 0.10; CFI = .99; SRMR = 0.03). Baseline SES was significantly positively associated with baseline parent positive communication and baseline parent-reported internalizing symptoms, but not baseline youth-reported internalizing symptoms. Baseline internalizing symptoms were significantly positively associated with follow-up internalizing symptoms within informant. Baseline parent positive communication was not significantly associated with either parent- or youth-reported internalizing symptoms at baseline or follow-up. There was a significant direct association between baseline SES and parent-reported internalizing symptoms at follow-up, but not youth-reported internalizing symptoms at follow-up. There was no significant indirect effect of baseline SES on follow-up internalizing symptoms via parent positive communication (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Significant path loadings for the model of family SES, parent positive communication and baseline and follow-up teen internalizing symptoms. Note. Only significant paths are shown. CO = Communication. LR = Listener Responsiveness. commT1 = baseline parent positive communication. ysrintT1 = baseline youth self-report internalizing. cbcintT1 = baseline parent-report internalizing. ysrintT2 = 6-month youth self-report internalizing. cbcintT2 = 6-month parent-report internalizing.

SEM analyses: Testing the Fit of the Model for Externalizing Symptoms

The data fit the full model well (χ2 = 15.45 (6), p = .02; RMSEA = .07, CI=0.03 to 0.11; CFI = 0.99; SRMR = 0.03). Baseline SES was significantly positively associated with baseline parent positive communication and parent-reported baseline externalizing symptoms, but not youth-reported baseline externalizing symptoms. Within informants, baseline externalizing symptoms were significantly positively associated with follow-up externalizing symptoms. Additionally, baseline parent positive communication was significantly negatively associated with parent-reported baseline externalizing symptoms. There was also a significant direct association between baseline SES and follow-up parent-reported externalizing symptoms. There was no significant direct association between baseline parent positive communication and follow-up externalizing symptoms; however, there was a significant indirect effect of baseline SES on follow-up parent-reported externalizing symptoms (β = −.05, p < .05) via parent positive communication and baseline externalizing symptoms (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Significant path loadings for the model of family SES, parent positive communication and baseline and follow-up teen externalizing symptoms. Note. Only significant paths are shown. Dotted line represents the indirect association between baseline SES and follow-up externalizing symptoms via baseline parent positive communication and baseline externalizing symptoms. CO = Communication. LR = Listener Responsiveness. commT1 = baseline parent positive communication. ysrextT1 = baseline youth self-report externalizing. cbcextT1 = baseline parent-report externalizing. ysrextT2 = 6-month youth self-report externalizing. cbcextT2 = 6-month parent-report externalizing.

Discussion

The current study extends previous research on adolescent mental health and the family stress model in several important ways. In our sample of primarily low-SES, urban, racially diverse youth seeking outpatient psychiatric treatment, we found partial support for the family stress model when predicting externalizing symptoms, but not internalizing symptoms, and when using parent-reported symptoms, but not youth-reported symptoms. Specifically, in the model for externalizing symptoms, baseline SES was positively associated with parent positive communication, and parent positive communication was negatively associated with parent-reported baseline externalizing symptoms. There was a strong positive association between baseline and follow-up externalizing symptoms. Further, baseline SES was associated with parent-reported externalizing symptoms at follow-up. Additionally, we found an indirect association between baseline SES and parent-reported follow-up externalizing symptoms via positive parent communication and baseline externalizing symptoms.

Notably, these associations were only significant with parent-reported symptoms. It is unlikely that the discrepancy in findings between youth and parent report is due to lower reliability or validity of youth self-reports, as extensive research documents that youth reports offer reliable and unique information about their symptoms, beyond the information obtained by parental reports (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001; De Los Reyes, 2011). Rather, our results build upon findings of reciprocal relations between youth mental health and parental behaviors, especially for externalizing problems (e.g., Williams & Steinberg, 2011). In particular, our results may suggest a cycle: youths’ externalizing behaviors observed by parents increase parental stress and decrease parents’ ability to communicate positively with their children, leading to subsequent youth problems. Youth-reported symptoms were not associated with SES or with parent positive communication. Prior research indicates that discrepancies in parent and child reports of youth problems are associated with more parent-child conflict and maternal stress (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2006). The lack of associations with youth reports may be characteristic of families of treatment-seeking youth, who may have larger discrepancies between parent and child perceptions of youth problems, and who experience higher levels of parent-child conflict and parental stress (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2006). Thus, it may be especially important for future studies to examine (and account for) discrepancies between parent and child reports to understand relationships between SES, family processes, and mental health for youth seeking treatment.

The findings for externalizing problems are consistent with previous research on the family stress model indicating a larger effect for externalizing problems compared to internalizing problems (Grant et al., 2003). Our results indicate that baseline SES has a direct negative association with baseline externalizing symptoms, and an indirect negative association with later externalizing problems. The indirect association occurs via three paths: first, the positive relationship between SES and parent positive communication, second, the negative relationship between parent positive communication and baseline externalizing symptoms, and third, the positive relationship between baseline and later externalizing symptoms. Interestingly, this indicates that parent positive communication was indirectly associated with later externalizing symptoms through communication's relationship with baseline externalizing symptoms. These results suggest that, in families living in low-SES conditions, parents may be able to use clear, direct and responsive communication to manage current externalizing problems and prevent them over time.

In contrast, in the model for internalizing symptoms, results did not support the family stress model. There were significant negative associations between baseline SES and parent-reported baseline and follow-up internalizing symptoms. However, there were no significant associations between parent positive communication and internalizing symptoms at baseline or follow-up, and there was no indirect relationship between SES and follow-up symptoms via parent positive communication. Our results are consistent with research documenting the relatively stronger relationship between parental behaviors and youth externalizing problems, compared to internalizing problems, in the context of low SES environments (Grant et al., 2003), which may result from the negative impact of youth externalizing behaviors on parenting (e.g., increasing parental hostility; see Williams & Steinberg, 2011). The results regarding internalizing symptoms may also differ from previous findings of the family stress model due to the nature of our sample—racially diverse urban youth seeking psychiatric care, many of whom had elevated levels of mental health problems at baseline. Participants were primarily ethnic minority urban youth who may have been exposed to a variety of contextual stressors beyond those caused by economic hardship and negative parenting behaviors, such as exposure to community violence, other stressors related to urban poverty, and stressors related to discrimination. These contextual stressors may play a larger role than parental behaviors in the development and maintenance of internalizing problems and may have a stronger impact on internalizing than externalizing problems, therefore weakening the effects of SES and parent positive communication on internalizing but not externalizing problems. For example, parents’ ability to communicate effectively (e.g., clearly communicate limits to their children) may reduce youths’ opportunities to engage in externalizing behaviors even in the context of these other risks, but clear communication may not reduce emotional distress for youth exposed to these contextual stressors.

Our findings suggest several directions for policy and intervention. The direct relationship between SES and adolescent psychopathology implies that poverty and poverty-related stressors are appropriate targets for youth internalizing and externalizing problems. For example, local and federal programs should directly target poverty and related difficulties (e.g., neighborhood safety, crowding, nutrition, access to health services) to improve mental health outcomes for these youth. In addition, clinical interventions should include coping skills to help youth manage stressors occurring in low-SES, urban environments (e.g., exposure to community violence). Similarly, the results regarding parent positive communication are consistent with treatment literature on the most effective interventions for internalizing and externalizing disorders. Specifically, individual interventions (e.g., cognitive restructuring) have a significant impact on internalizing problems (Clarke et al., 2001), while externalizing problems are treated most effectively with family-based and multi-systemic interventions, especially for lower-income urban youth (Henggeler, 1999). Our results suggest that even if parent communication is poor, youth may still benefit from individual interventions that improve internalizing problems (e.g., individual cognitive-behavioral therapy). In contrast, our results suggest that family-based approaches are integral to treating externalizing problems. Since our results were significant for parent-report only, parents may benefit from both positive communication skills (e.g., non-verbal listening skills, providing clear explanations) and coping skills to help manage stress caused by youths’ externalizing behaviors. By helping parents cope with their teens’ externalizing behaviors, they may become less distressed and may use more positive communication, which may ultimately have a positive impact on youths’ externalizing problems.

Study strengths such as sample characteristics, multiple and culturally sensitive methodologies, and theory-driven hypotheses should be considered along with the following study limitations. First, while we accounted for baseline symptoms and utilized two waves of data, we did not examine each process at a different timepoint, as is recommended to obtain unbiased effect sizes and establish directionality among processes (Cole & Maxwell, 2003; Maxwell & Cole, 2007). Hence, findings do not indicate that effects will be sustained over time (indeed, effect sizes may be inflated) nor do they determine directionality between variables. This study represents an initial step in examining the family stress model with treatment-seeking, lower income urban youth. It will be important for future studies to address the potential transactional relationships between SES, adolescent symptoms and parent communication by examining each variable over multiple waves to determine the size and directions of these effects over time in this population. Second, most caregivers in this study were female. Although we included male caregivers, we did not have sufficient power to examine the potentially different effects of male and female caregivers. Third, our results may not generalize to non-treatment seeking youth from urban communities. Fourth, we did not examine youth and parent perceptions about reasons for seeking treatment, nor did we assess youths’ or families’ levels of functional impairment. Additionally, while adolescents are described as treatment-seeking, treatment utilization varied among participants (e.g., only 55% were receiving treatment at follow-up), and we did not assess the extent or level of treatment utilization in the period from baseline to follow-up. Future studies would benefit from a more detailed assessment of youth and family functional impairment and level of treatment utilization, which may be helpful to put informant discrepancies in context, establish the ecological validity of our findings with this population, and may temper our findings based on the extent of treatment utilization. Finally, we used parent reports of family SES as a proxy for economic hardship, yet SES alone does not capture the full impact of economic hardship and its associated stressors. Future studies should use more comprehensive assessments, such as family income and negative financial events (e.g., a parent losing a job), as well as contextual factors associated with economic hardship within an urban environment (e.g., community violence exposure, neighborhood quality, crowding). Subsequent research should examine these contextual predictors of youth mental health in conjunction with the family stress model in a low-income, urban, treatment-seeking population, and in doing so identify specific intervention mechanisms to improve mental health problems in these high-risk youth. Despite these limitations, this study extends prior research on adolescent mental health in a diverse sample of urban youth seeking outpatient psychiatric care. Our findings suggest the importance of directly addressing economic hardship and related stressors for treatment-seeking youth, and that families of youth with externalizing problems may benefit from interventions that target parental skills such as positive communication and coping.

Contributor Information

Erin M. Rodriguez, 1747 W. Roosevelt Rd., MC 747, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL 60612. erodriguez@psych.uic.edu

Sara R. Nichols, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL 60611.

Shabnam Javdani, Steinhardt School of Culture, Education and Human Development, New York University, New York, NY 10003..

Erin Emerson, University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health, Chicago, IL 60612..

Geri R. Donenberg, University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health, Chicago, IL 60612.

References

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; Burlington, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:545–557. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Prelow HM, Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Michaels ML, Roosa MW, Tein J. Pathways from family economic conditions to adolescents' distress: Supportive parenting, stressors outside the family, and deviant peers. Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn R. From parent to child to parent...: Paths in and out of problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41:515–529. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9692-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X. Linking parenting processes and self-regulation to psychological functioning and alcohol use during early adolescence. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:82–94. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, Hadley W, Stewart A, Lescano C, Whitely L, Donenberg G, DiClemente R, Project STYLE Study Group Psychiatric disorders and sexual risk among adolescents in mental health treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:590–597. doi: 10.1037/a0019632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke GN, Hornbrook M, Lynch F, Polen M, Gale J, Beardslee W, Seeley J. A randomized trial of a group cognitive intervention for preventing depression in adolescent offspring of depressed parents. Archives of general psychiatry. 2001;58:1127–1134. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.12.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1992;1:98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ. Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:361–373. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ge X, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development. 1994;65:541–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello E, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Egger H, Angold A. 10-year research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:972–986. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000172552.41596.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A. Introduction to the special section: More than measurement error: Discovering meaning behind informant discrepancies in clinical assessments of children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40:1–9. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.533405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: a critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:483–509. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in assessing child dysfunction relate to dysfunction within mother-child interactions. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2006;15:643–661. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9031-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donenberg GR, Emerson E, Mackesy-Amiti ME. Sexual risk among African American girls: Psychopathology and mother–daughter relationships. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:153–158. doi: 10.1037/a0022837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donenberg G, Schwartz R, Emerson E, Wilson H, Bryant F, Coleman G. Applying a cognitive-behavioral model of HIV-risk to youths in psychiatric care. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2005;17:200–216. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.4.200.66532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donenberg G, Weisz J. Experimental task and speaker effects on parent-child interactions of aggressive and depressed/anxious children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:367–387. doi: 10.1023/a:1025733023979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J. Family poverty, welfare reform, and child development. Child Development. 2000;71:188–196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Stuhlmacher AF, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Halpert JA. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:447–466. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW. Multisystemic therapy: An overview of clinical procedures, outcomes, and policy implications. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 1999;4:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. Yale University; New Haven, CN: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among US children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz BN, Esparza P, Carter JS, Grant KE, Meyerson DA. Intervening processes in the relationship between neighborhood characteristics and psychological symptoms in urban youth. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2012;32:650–680. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Ries Merikangas K. Mood disorders in children and adolescents: an epidemiologic perspective. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49:1002–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Lochman JE. Moving beyond efficacy and effectiveness in child and adolescent intervention research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:373–382. doi: 10.1037/a0015954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung JT, Shek DT. Poverty and adolescent developmental outcomes: a critical review. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2011;23:109–114. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2011.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Health disparities in youth and families. Springer; New York: 2011. How money matters for children’s socioemotional adjustment: Family processes and parental investment. pp. 33–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales: Instrument summary. In: Kerig PK, Lindahl KM, editors. Family observational coding systems. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Nakamura EF, Kessler RC. Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2009;11:7–20. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.1/krmerikangas. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S, Seidman E, Yoshikawa H, Rivera AC, Allen L, Aber JL. Contextual competence: Multiple manifestations among urban adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;35:65–82. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-1890-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche KM, Ghazarian SR, Little TD, Leventhal T. Understanding links between punitive parenting and adolescent adjustment: The relevance of context and reciprocal associations. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:448–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES. Children's reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development. 1965;36:413–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JC, Barton-Henry ML, Pruzinsky T. Assessing child-rearing behaviors: A comparison of ratings made by mother, father, child, and sibling on the CRPBI. Child Development. 1985;56:462–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlomer GL, Bauman S, Card NA. Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57:1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0018082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MT, Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA, Willett JB. Trajectories of family management practices and early adolescent behavioral outcomes. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:1324–1341. doi: 10.1037/a0024026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LR, Steinberg L. Reciprocal relations between parenting and adjustment in a sample of juvenile offenders. Child Development. 2011;82:633–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]