Abstract

Objectives

This study examined both cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between felt age and cognitive-affective symptom dimensions of depression in late life.

Method

Data for this study came from two interview waves (T1 and T2) of the National Health and Aging Trend Study. Sample persons (n = 6680) who resided in their own or another’s home at T1 were included. At T2 (one year later), 5414 of the original 6680 were interviewed and depressive symptom data were available for 5371 sample persons. The associations between felt age and depressive symptoms were analyzed using stepwise linear regression analyses.

Results

At T1, (1) more than 70% of the sample felt younger and 7% felt older than their chronological age; and (2) younger felt age was associated with lower depressive symptoms, and older felt age was associated with higher depressive symptoms. Controlling for T1 depressive symptoms and health conditions, older felt age at T1 also predicted higher depressive symptoms at T2; however, chronological age and felt age explained only a small amount of variance in depressive symptom scores.

Conclusion

The self-enhancement or self-protection function of younger felt age at T1 does not appear to extend longitudinally to T2, while the negative depressive effect of older felt age at T1 extends to T2.

Keywords: depressive symptoms, chronological age, felt age

Introduction

Prevalence rates of major depression and other mental disorders are lower in older adults (65 years or older) than in younger age groups, and the rates continue to decline with advanced age (Byers, Yaffe, Covinsky, Friedman, & Bruce, 2010; Gum, King-Kallimanis, & Kohn, 2009; Kessler et al., 2010). Depressive symptoms in general also tend to decline with age, although a few studies have found that these symptoms rise among those aged 70 years or older due to declines in physical and functional health (Choi & Kim, 2007; Gats & Hurwicz, 1990; Jorm, 2000; Mirowsky & Ross, 1992). Because older adults are an increasingly diverse group of individuals with a wide range of chronological ages as well as physical, mental, and cognitive health conditions, age differences in depressive symptoms continue to be an important area of research.

Research also shows that older adults tend to feel younger than their chronological age and that the discrepancy between felt age and chronological age increases with advanced chronological age (Barak, 2009; Barak & Stern, 1986; Cleaver & Muller, 2002; Hubley & Hultsch, 1994; Montepare & Lachman, 1989; Uotinen, Rantanen, Suutama, & Ruoppila, 2006). Feeling younger has been found to be significantly associated with psychological health factors such as optimism and higher self-efficacy (Teuscher, 2009); higher levels of life satisfaction and positive affect (Westerhof & Barrett, 2005); internal locus of control and extraversion (Hubley & Hultsch, 1994); and higher levels of personal growth and generativity (Ward, 2010). These studies also found that psychological variables influence subjective age independent of health variables rather than moderating the relationship between subjective age and health. Given the significant link between felt age and psychological health in late life, a connection between felt age and depression is also highly probable. A few cross-sectional studies (Infurna, Gerstorf, Robertson, Berg, & Zarit, 2010; Keyes & Westerhof, 2012) attest to this link between younger felt age and lower depressive symptoms and lower risk for major depression; however, little research has been done on the longitudinal relationship between these variables. The purpose of this study was to examine both cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between felt age and depressive symptoms using a nationally representative sample of older adults.

Conceptual framework and hypotheses

Despite the highly consistent empirical data on older adults’ subjective age bias, theoretically founded psychological explanations for this phenomenon remain lacking. One promising theoretical approach might be related to positivity bias or positive illusions (Teuscher, 2009). According to this approach, older adults who report feeling younger than their chronological age are engaging in self-motivation, self-enhancement, and self-protection, since to feel, look, and act younger is generally considered beneficial and contributes to well-being and enhanced functioning as it tends to prevent negative age stereotypes from becoming self-defining (Montepare, 2009; Teuscher, 2009). Empirical data support that older adults who feel younger than their chronological age have an expanded future time perspective and are more likely to psychologically dissociate themselves from their age group when negative age stereotypes are salient (Weiss & Freund, 2012; Weiss & Lang, 2012). If positivity bias and self-enhancement and self-protection from negative age-related information explain subjective age bias, then we can expect those who feel younger to report better psychological health and lower depressive symptoms and those who feel older to report worse psychological health and higher depressive symptoms. For example, among US adults aged 55 years or older, Keyes and Westerhof (2012) found that chronological age was a stronger predictor of major depression than felt age, but younger felt age lowered this risk. Infurna et al. (2010) also found that reporting fewer depressive symptoms independently predicted whether or not Swedish octogenarians endorsed the ‘not feeling old’ over ‘feeling old’ response category.

The present study focused on the cognitive-affective symptom dimension of depression. Research suggests that physical health problems are less likely to affect cognitive-affective than somatic depressive symptoms (Linke et al., 2009; Michal et al., 2013). The study hypotheses are: (H1) controlling for gender, race/ethnicity, health conditions, and chronological age, felt age that is younger than chronological age will be associated with lower depressive symptoms at baseline (time 1 [T1]), whereas felt age that is older than chronological age will be associated with higher depressive symptoms; and (H2) controlling for depressive symptoms at T1, felt age that is younger than chronological age at T1 will be associated with lower depressive symptoms one year after baseline (time 2 [T2]), whereas felt age that is older than chronological age at T1 will be associated with higher depressive symptoms at T2.

Methods

Data and sample

Data for this study came from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) waves 1 (T1) and 2 (T2) conducted in 2011 and 2012, respectively. The sample is representative of US Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years or older who resided in the community in their own or another’s home or in residential care settings (Kasper & Freedman, 2012). In the present study, we include the 6680 T1 sample persons who resided in their own or another’s home and excluded those in nursing homes (n = 468) or other such settings (n = 412) as well as those represented by proxy respondents (e.g., their spouse or child [n = 517]) due to dementia, illness, hearing impairment, and/or speech impairment. At T1, 6639 sample persons responded to questions about depressive symptoms. At T2, 5414 (5326 in their own or another’s home, 25 in nursing homes, and 63 in other residential facilities) of the 6680 T1 sample persons were reinterviewed – 5243 via self-interview and 171 via proxy-interview – and 5371 answered depressive symptom questions.

Measures

Depressive symptoms at both waves were measured with the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2003), which captures the cognitive/affective symptoms of anhedonia and depressed mood by asking ‘Over the last month, how often have you/has the sample person (a) had little interest or pleasure in doing things; and (b) felt down, depressed, or hopeless?’ Responses were based on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all; 2 = several days; 3 = more than half the days; 4 = nearly every day). The combined score was used as a symptom severity score.

Chronological age was measured as age in years, and age group refers to grouping sample persons into one of four categories: aged 65–69 (reference group); aged 70–79; aged 80–89; and aged 90+.

Felt age is one component of subjective age (e.g., felt age, look age, and act age), and it has been consistently measured in previous research by asking respondents how old they feel. In the present study, it was based on each sample person’s response to the following question: ‘Sometimes people feel older or younger than their age. During the last month, what age did you feel most of the time?’ Sample persons were grouped into four categories: feeling exactly the same as their chronological age (i.e., felt age = chronological age; reference group); feeling younger; feeling older; and missing (4.45% of the study sample did not know [DK] or refused to provide [RF] their felt age).

Health conditions included the number of chronic illnesses diagnosed by a doctor ranging from 0 to 8 (including high blood pressure, heart attack/heart disease, arthritis, osteoporosis, diabetes, lung disease, stroke, and cancer); the number of impairments in activities and instrumental activities of daily living (ADLs/IADLs) ranging from 0 to 14; and whether or not body pain limited activities in the past month (yes or no).

Health perceptions were sample persons’ self-ratings of health and memory, each measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = excellent to 5 = poor).

Demographic characteristics were gender and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white [reference group], non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, all others).

Analysis

Hypotheses were tested with stepwise linear regression analyses using the svy function of Stata13/MP to account for NHATS’ multistage cluster sampling design. T1 and T2 depression scores were the dependent variables. Independent variables were entered as follows: step 1 – gender, race/ethnicity, health conditions, and perceived health variables; step 2 – chronological age group; and step 3 – felt age group. Because T2 depression scores were missing for 1266 sample persons due to attrition (including refusal and death), a λ selection term for attrition was also controlled in the regression model that tested H2 (Heckman, 1979). This selection term, created in a logistic regression model (with chronological age, education, number of chronic illnesses and ADL/IADL impairments, and diagnosis of dementia as predictors), estimated the predicted probability of not reporting T2 depression data due to attrition versus reporting T2 depression data.

Results

Sample characteristics and bivariate analyses

Of the sample, 70.75% reported feeling younger than their chronological age; 17.96% reported feeling the same age; and 6.85% reported feeling older (see Table 1). On average, those who reported feeling younger felt 17.64 (SE = 0.17) years younger, and those who reported feeling older felt 7.31 (SE = 0.49) years older. Further analyses (with Bonferroni corrections) found that of those who reported their felt age, the discrepancy between felt age and chronological age was greater for the 90+ age group than the other three group (−17.44 [SE = 0.95] years for the 90+ group vs. −11.91 [SE = 0.40] years for the 60–69 group, −12.41 [SE = 0.25] years for the 70–79 group, and −13.13 [SE = 0.31] years for the 80–89 group; F (3, 54) = 9.55, p < .001). ANOVA results (see Table 2) also show that T1 depressive symptom scores were not associated with chronological age group, but they were significantly associated with felt age group. T2 depression scores were significantly associated with both chronological age group and felt age group.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (n = 6680).

| Age (yrs) | 74.31 (1.00) |

| Age group (%) | |

| 65–69 | 30.13 |

| 70–79 | 45.57 |

| 80–89 | 21.57 |

| 90+ | 2.73 |

| Felt age (yrs) | 61.64 (2.58) |

| Felt age group (%) | |

| Felt younger | 70.75 |

| Felt the same | 17.96 |

| Felt older | 6.85 |

| Missing (DK/RF) | 4.45 |

| Gender (%) | |

| Male | 44.20 |

| Female | 55.80 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 81.11 |

| Black | 8.02 |

| Hispanic | 6.73 |

| All other races | 4.14 |

| Education | |

| <High school/DK/refused | 21.43 |

| High school diploma or GED | 27.08 |

| Some college or associate degree | 26.61 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 24.88 |

| No. of chronic medical conditions | 2.34 (0.02) |

| No. of ADL/IADL impairments1 (0–14) | 1.03 (0.06) |

| Had pain limiting activities (%) | 28.39 |

| Self-rated health (1–5) | 2.63 (0.02) |

| Self-rated memory (1–5) | 2.57 (0.12) |

| Depression score at T1 (2–8; n = 6639) | 2.87 (0.02) |

| Depression score at T2 (2–8; n = 5371) | 2.84 (0.03) |

Note: All statistics refer to time 1 (T1) characteristics, unless specified otherwise, and weighted.

ADLs: Eating, bathing, toileting, dressing, getting in and out of bed, getting in and out of chair, and walking inside; IADLs: Preparing meals, doing laundry, doing light housework, shopping for groceries, managing money, taking medication, and making telephone calls. The small number of missing values (did not know [DK] or refused to answer [RF]) in some of the medical conditions and ADL/IADL variables were treated as the absence of a diagnosis or impairment to arrive at conservative estimates.

Table 2.

Bivariate relationship between chronological age, felt age, and depressive symptoms.

| T1 depressive symptoms n = 6639 | T2 depressive symptoms n = 5371 | |

|---|---|---|

| Chronological age | F (3, 54) = 1.66, p = 0.185 | F (3, 54) = 12.16, p < .001 |

| 65–69 | 2.87 (0.04)a | 2.75 (0.04)a |

| 70–79 | 2.87 (0.03)b | 2.84 (0.03)b |

| 80–89 | 2.96 (0.04)c | 2.94 (0.04)c |

| 90+ | 2.92 (0.06)d | 3.20 (0.09)d |

| Multiple group comparison1 | a = b = c = d | a, b, c < d; a = b; a < c; b = c |

| Felt age | F (3, 54) = 80.19, p < .001 | F (3, 54) = 43.07, p < .001 |

| Feeling younger | 2.72 (0.03)a | 2.70 (0.03)a |

| Feeling the same age | 3.16 (0.05)b | 3.09 (0.05)b |

| Feeling older | 3.91 (0.09)c | 3.65 (0.09)c |

| DK/RF | 2.96 (0.08)d | 2.96 (0.10)d |

| Multiple group comparison1 | a, b, d < c; a < b; a < d; b = d | a, b, d < c; a < b; a = d; b = d |

Note: All statistics are weighted.

Bonferroni corrected; α < .05.

Multivariate analysis results

At T1, gender, race/ethnicity, health conditions, and perceived health explained 19.8% of the variance in depressive symptoms scores (see Table 3). Compared to the 65–69 age group, the other three age groups had lower depressive symptoms; however, chronological age explained only 0.2% of the variance in depressive symptoms. The addition of felt age explained another 1.1% of the variance. As hypothesized (H1), compared to felt age that was the same as chronological age, younger felt age was associated with lower depressive symptoms and older felt age with higher depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

Relationship between felt age and T1 and T2 depressive symptoms.

| T1 (n = 6639)

|

T2 (n = 5371)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | |

| Predicted probability1 | 1.55 (0.64)* | 1.42 (0.63)* | 1.33 (0.63)* | |||

| T1 depressive symptoms | 0.36 (0.02)*** | 0.36 (0.02)*** | 0.36 (0.02)*** | |||

| Male | −0.08 (0.04)* | −0.08 (0.04)* | −0.08 (0.04)* | −0.07 (0.03)* | −0.07 (0.03)* | −0.06 (0.03)* |

| Black | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.06 (0.040 | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.08 (0.04) |

| Hispanic | 0.20 (0.12) | 0.19 (0.12) | 0.20 (0.12) | 0.18 (0.11) | 0.19 (0.11) | 0.20 (0.11) |

| Other race | −0.15 (1.00) | −0.17 (0.10) | −0.13 (0.10) | −0.22 (0.11)* | −0.21 (0.11) | −0.21 (0.12) |

| Chronic illnesses | 0.06 (0.01)*** | 0.06 (.01)*** | 0.06 (0.01)*** | 0.05 (0.01)*** | 0.05 (0.01)*** | 0.05 (0.01)*** |

| ADL/IADL limitations | 0.05 (0.01)*** | 0.05 (0.01)*** | 0.05 (0.01)*** | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| Pain limiting activities | 0.43 (0.04)*** | 0.42 (0.04)*** | 0.39 (0.04)*** | 0.17 (0.05)** | 0.17 (0.05)** | 0.16 (0.02)** |

| Self-rated health | 0.28 (0.02)*** | 0.28 (0.02)*** | 0.25 (0.02)*** | 0.08 (0.02)** | 0.08 (0.02)** | 0.06 (0.02)** |

| Self-rated memory | 0.14 (0.03) *** | 0.14 (0.03)*** | 0.14 (0.03)*** | 0.10 (0.02)*** | 0.10 (0.02)*** | 0.10 (0.02)*** |

| Age 70–79 | −0.09 (0.04)* | −0.07 (0.04) | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.04) | ||

| Age 80–89 | −0.14 (0.05)** | −0.11 (0.05)* | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.05) | ||

| Age 90+ | −0.20 (0.08)* | −0.16 (0.08)* | 0.33 (0.08)*** | 0.34 (0.08)*** | ||

| Felt younger | −0.13 (0.05)* | −0.10 (0.05) | ||||

| Felt older | 0.45 (0.11)*** | 0.20 (0.08)* | ||||

| Felt age DK/RF | −0.11 (0.10) | −0.01 (0.10) | ||||

| Constant | 1.50 (0.08)*** | 1.55 (0.08)*** | 1.71 (0.10)*** | 0.91 (0.10)*** | 090 (0.10)*** | 1.03 (0.11)*** |

| R2 | .198 | .200 | .211 | .266 | .267 | .271 |

Of not reporting depressive symptoms due to attrition.

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05.

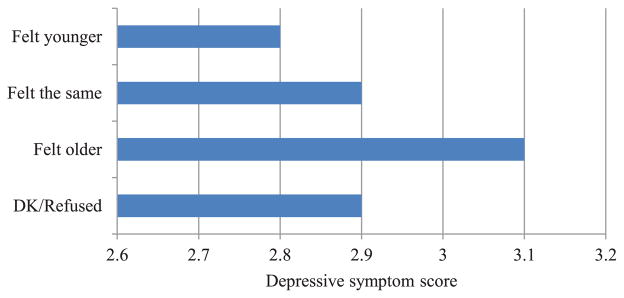

At T2, the λ selection term, gender, race/ethnicity, T1 depressive symptoms, T1 health conditions, and T1 perceived health explained 26.6% of the variance in depressive symptom scores. Of the chronological age groups, only the 90+ age group, compared to the 65–69 group, had higher depressive symptoms, but chronological age explained only 0.1% of the variance. Compared to T1 felt age that was the same as chronological age, older felt age was significantly associated with higher T2 depressive symptoms, while younger felt age was not associated with T2 depressive symptoms. Felt age explained only 0.4% of the variance. Thus, H2 was only partially supported. Figure 1 presents T2 mean depressive symptom scores by T1 felt age group, adjusted for other covariates.

Figure 1.

Mean Depressive Symptom Scores at T2 by T1 Felt Age Group. Adjusted for Other Covariates.1 1λ selection term; T1 depressive symptoms; gender; race/ethnicity; number of chronic illnesses; number of ADL/IADL impairments; pain limiting activities; self-rated health; self-rated memory; and chronological age.

Discussion

As in previous studies, more than 70% of older adults in this study reported feeling younger than their chronological age, and the discrepancy between chronological age and felt age was the greatest among the oldest adults (90+ years of age). If feeling younger is a self-enhancement strategy for older adults (Teuscher, 2009), the oldest old are likely to have the greatest motivation for enhancing and protecting their subjective sense of well-being since they, on average, have the greatest challenges in health and functioning. The oldest old are also likely to have the greatest need to engage in self-protective and defensive strategies by adopting a younger felt age and dis-identifying with members of their own age group who tend to represent the most salient negative age stereotypes (Weiss & Lang, 2012). As summarized, previous studies found that younger felt age, as self-enhancement or protective illusion, was associated with higher subjective well-being (Teuscher, 2009; Westerhof & Barrett, 2005). However, the present study found that when health conditions and perceived health are controlled, chronological age and felt age accounted for only a miniscule amount of variance in cognitive-affective depressive symptoms in late life, both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. Cross-sectionally, both older chronological age and younger felt age were associated with lower depressive symptoms. However, when T1 depressive symptoms were controlled, T1 younger felt age was not a significant predictor of T2 depressive symptoms, but T1 older felt age predicted higher T2 depressive symptoms. Thus, the self-enhancement and self-protection function of younger felt age does not appear to extend longitudinally, while the negative depressive effect of older felt age at T1 extended to T2 independent of T1 depressive symptoms and health status. A possible explanation for these findings is that the 7% of sample persons that reported an older felt age may have had significantly worse psychosocial, as well as medical, histories than their peers who reported feeling younger. The findings also suggest that the adoption of a negative or stigmatized social identity of older people may have long-term deleterious effects on older adults’ psychological well-being.

Despite the use of two waves of data in this study, causal inferences are difficult to make due to the use of survey methodology and the lack of information on the sample’s previous mental health problems. Another study limitation concerns the depression measure. Anhedonia and depressed mood are two core symptoms of late-life depression, but each was measured with only a single item. Data on previous mental health problems and a full-length depression scale would have enabled more in-depth examination of felt age and its relationship to depressive symptoms. In addition, although the self-reported measure of felt age appears to be a reasonable approach and has been widely used in previous research, we have not found any evaluation of this measures’ reliability or validity.

Despite these limitations, this study provides the following insights into the relationship between felt age and depressive symptoms in late life: (1) chronological age and felt age are independent correlates of depressive symptoms; and (2) older felt age may signal a future decline in mood and other mental health symptoms in older adults that may warrant intervention. Further research is needed to examine how and why older felt age may predict higher depressive symptoms over time, independent of chronological age and earlier depressive symptoms and health conditions.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by an internal research grant from the University of Texas at Austin.

References

- Barak B. Age identity: A cross-cultural global approach. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33:2–11. doi: 10.1177/0165025408099485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barak B, Stern B. Subjective age correlates: A research note. The Gerontologist. 1986;23:571–578. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers AL, Yaffe K, Covinsky KE, Friedman MB, Bruce ML. High occurrence of mood and anxiety disorders among older adults: The National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General psychiatry. 2010;67:489–496. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, Kim J. Age group differences in depressive symptoms among older adults with functional impairments. Health & Social Work. 2007;32:177–188. doi: 10.1093/hsw/32.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleaver M, Muller TE. I want to pretend I’m eleven years younger: Subjective aged seniors’ motives for vacation travel. Social Indicators Research. 2002;60:227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Gats M, Hurwicz ML. Are old people more depressed? Cross-sectional data on CES-D factors. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5:284–290. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gum A, King-Kallimanis B, Kohn R. Prevalence of mood, anxiety, and substance disorders for older Americans in the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009;17:769–781. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318ad4f5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JI. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica. 1979;45:153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Hubley AM, Hultsch DF. The relationship of personality trait variables to subjective age identity in older adults. Research on Aging. 1994;16:415–439. doi: 10.1177/0164027594164005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Infurna FJ, Gerstorf D, Robertson S, Berg S, Zarit SH. The nature and cross-domain correlates of subjective age in the oldest old: Evidence from the OCTO Study. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25:470–476. doi: 10.1037/a0017979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF. Does old age reduce the risk of anxiety and depression? A review of epidemiological studies across the adult life span. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30:11–22. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper JD, Freedman VA. National Health and Aging Trends Study Round 1 User Guide: Final Release. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; 2012. Retrieved from http://www.nhats.org/scripts/documents/NHATS_Round_1_User_Guide_Final_Release.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Bromet E, Hwang I, Sampson N, Shahly V. Age differences in major depression: Results from the National Comorbidity Surveys Replication (NCS-R) Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:225–243. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM, Westerhof GJ. Chronological and subjective age differences in flourishing mental health and major depressive episode. Aging & Mental Health. 2012;16:67–74. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.596811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire 2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care. 2003;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke SE, Rutledge T, Johnson BD, Vaccarino V, Bittner V, Cornell CE, Bairey Merz CN. Depressive symptom dimensions and cardiovascular prognosis among women with suspected myocardial ischemia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:499–507. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michal M, Wiltink J, Kirschner Y, Wild PS, Munzel T, Ojeda FM, Beutel ME. Differential associations of depressive symptom dimensions with cardiovascular disease in the community: Results from the Gutenberg Health Study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e72014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Age and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1992;33:187–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montepare JM. Subjective age: Toward a guiding lifespan framework. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33:42–46. doi: 10.1177/0165025408095551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montepare JM, Lachman ME. You are only as old as you feel’: Self-perceptions of age, fears of aging, and life satisfaction from adolescence to old age. Psychology and Aging. 1989;4:73–78. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.4.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teuscher U. Subjective age bias: A motivational and information processing approach. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33:22–31. doi: 10.1177/0165025408099487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uotinen V, Rantanen T, Suutama T, Ruoppila I. Change in subjective age among older people over an eight-year follow-up: ‘Getting older and feeling younger?’. Experimental Aging Research. 2006;32:381–393. doi: 10.1080/03610730600875759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward RA. How old am I? Perceived age in middle and later life. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2010;71:167–184. doi: 10.2190/AG.71.3.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D, Freund AM. Still young at heart: Negative age-related information motivates distancing from same-aged people. Psychology and Aging. 2012;27:173–180. doi: 10.1037/a0024819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D, Lang FR. “They” are old but “I” feel younger: Age-group dissociation as a self-protective strategy in old age. Psychology and Aging. 2012;27:153–163. doi: 10.1037/a0024887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof GJ, Barrett AE. Age identity and subjective well-being: A comparison of the United States and Germany. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences. 2005;60:129–136. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.3.S129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]