Abstract

Too often, populations experiencing the greatest burden of disease and disparities in health outcomes are left out of or ineffectively involved in academic-led efforts to address issues that impact them the most. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is an approach increasingly being used to address these issues, but the science of CBPR is still viewed by many as a nascent field. Important to the development of the science of CBPR is documentation of the partnership process, particularly capacity building activities important to establishing the CBPR research infrastructure. This paper uses a CBPR Logic Model as a structure for documenting partnership capacity building activities of a long-term community-academic partnership addressing public health issues in Arkansas, U.S. Illustrative activities, programs, and experiences are described for each of the model’s four constructs: context, group dynamics, interventions, and outcomes. Lessons learned through this process were: capacity building is required by both academic and community partners; shared activities provide a common base of experiences and expectations; and creating a common language facilitates dialogue about difficult issues. Development of community partnerships with one institutional unit promoted community engagement institution-wide, enhanced individual and partnership capacity, and increased opportunity to address priority issues.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, partnerships, capacity building

Introduction

Too often, populations experiencing the greatest burden of disease and disparities in health outcomes are left out of or ineffectively involved in academic-led efforts to address the issues that impact them the most. This institutional or “expert”-driven approach, traditionally viewed as more efficient and easy to control, is often too narrowly construed and of limited impact when translated into practice. This “disconnect” has led to a movement of scholarship of engagement (1), which requires an alternative paradigm based on equity, collaboration, and transformative action on issues of importance to the community (2). Many communities have embraced deliberation as a mechanism for dialogue, identifying needs, and initiating action (3,4). Others have used a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to address these issues with outside researchers (5,6). Although now more widely accepted as critical to translating research into practice (7,8), the science of CBPR is still viewed by many as a nascent field (9).

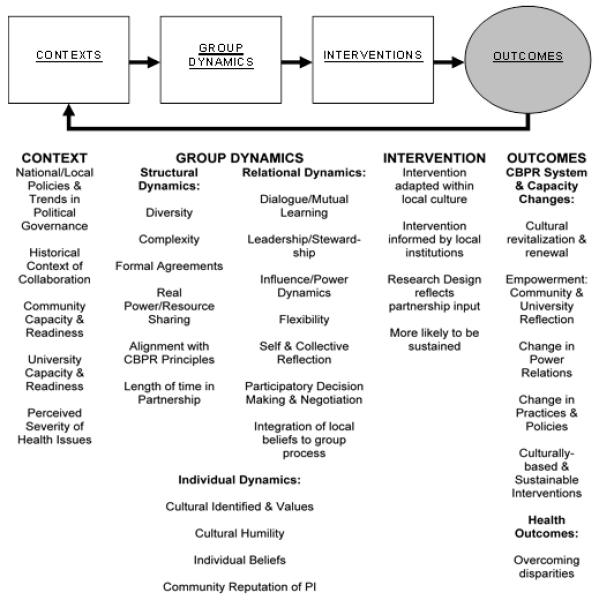

Important to the development of the science of CBPR is documentation of the partnership process, particularly partnership capacity building activities important to establishing a community-based research infrastructure that can support CBPR. This paper uses Wallerstein et al’s CBPR Logic Model (9) as a structure for documenting capacity building activities of long-term community-academic partnerships addressing public health issues in Arkansas, U.S. Wallerstein’s model was produced using a systematic process including collection and analysis of primary data, synthesis of the literature, and input from a national advisory committee of CBPR experts. This model describes multiple constructs comprising the context of partnerships including structural inequities in socio-economic and environmental factors, and cultural influences over risk and protection; national and local policies and trends; community and university capacity and readiness, and perceived severity and salience of the health issue.

Background

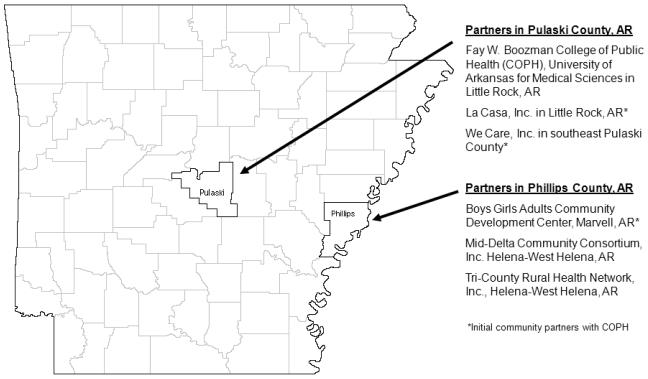

The Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health (COPH) at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) was founded in 2001, and immediately established the Office of Community-Based Public Health (OCBPH) based on the college’s philosophy that “community lies at the heart of public health” (10,11). In the COPH’s first year, two minority Arkansans with extensive community and organizational experience were hired to serve as community liaisons and to develop partnerships with community-based organizations (CBOs) in Phillips County (the focus of this paper) and Pulaski County. Boys Girls Adults Community Development Center (BGACDC), based in Arkansas’ Mississippi River Delta region, was selected as an initial CBO partner. Also that year, network development funding from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) was secured to establish Mid-Delta Community Consortium (MDCC), a CBO providing technical assistance and funding to rural health networks for health program planning and implementation in the Delta region through its Arkansas Delta Rural Development Network (ADRDN) program. MDCC’s director also serves as a COPH community liaison. The Tri-County Rural Health Network (TCRHN) formed in 2003, with ADRDN support, and became a COPH partner in 2004 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Partner Locations in Arkansas

These partnerships focus on improving the health and quality of life of individuals, families, and communities and on achieving health equity. Research is one among several mechanisms for achieving this goal. Indeed, partnership activities also include bidirectional technical assistance, program and resource development and sustainability, student service learning, community participation in classroom instruction, and community organizing.

UAMS and its COPH are located in Little Rock (the state capital), Pulaski County, Arkansas, U.S. UAMS is a major regional academic health center with five colleges and a graduate school, eight Area Health Education Centers, and six institutes of excellence (12). MDCC and TCRHN are located in Helena-West Helena, and BGACDC is in Marvell, all in Phillips County, 120 miles east of Pulaski County (Figure 1). Delta residents are primarily African American, have lower educational and employment levels, lower median household income, and a higher percentage living in poverty compared to those living in Little Rock or the state as a whole, although Little Rock and Arkansas lag behind the country on these same indicators. Phillips County has higher levels of mortality when compared to Pulaski County and Arkansas, U.S. as a whole, and racial health disparities are present. While access to quality healthcare is a factor in such disparities, structural determinants, such as political representation and control of major economic assets, also play an important role (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected Demographic Characteristics and Mortality Rates of Partnership Communities

| Little Rock |

Pulaski County |

Helena | West Helena |

Marvell | Phillips County |

AR | US | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Total population | 191,130 | 381,907 | 6,323 | 8,689 | 1,395 | 20,921 | 2.9 mil | 307 mil |

| Median age, years | 36.2 | 37.0 | 31.7 | 30.0 | 37.6 | 35.7 | 37.1 | 36.7 |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 52.1% | 60.8% | 30.6% | 32.8% | 40.4% | 36.5% | 80.6% | 74.3% |

| Black/African American | 41.6% | 34.7% | 67.9% | 65.7% | 58.1% | 61.5% | 15.8% | 12.3% |

| Education | ||||||||

| High School grad or higher | 89.6% | 84.4% | 62.3% | 64.4% | 64.6% | 62.2% | 75.3% | 84.5% |

| College Degree or higher | 39.0% | 21.1% | 17.4% | 12.0% | 13.9% | 12.4% | 16.7% | 27.4% |

| In Labor Force | 68.4% | 67.8% | 48.0% | 55.1% | 48.7% | 56.6% | 61.1% | 65.2% |

| Income | ||||||||

| Median household income | $44,480 | $45,215 | $18,662 | $21,130 | $22,368 | $26,436 | $38,820 | $52,175 |

| Persons in poverty | 12.2% | 16.5% | 38.4% | 30.9% | 22.6% | 34.9% | 17.3% | 9.6% |

| Mortality Rates | ||||||||

| All Cause | ||||||||

| Total | na | 930.2 | na | na | na | 1228.5 | 931.2 | 821.7 |

| White | na | 865.2 | na | na | na | 1091.1 | 905.1 | 806.3 |

| Black/African American | na | 1158.7 | na | na | na | 1369.2 | 1160.4 | 1051.2 |

| Heart Disease | ||||||||

| Total | na | 80.8 | na | na | na | 117.3 | 80.6 | 65.5 |

| White | na | 75.8 | na | na | na | 90.9 | 77.3 | 62.6 |

| Black/African American | na | 99.8 | na | na | na | 146.6 | 108.7 | 85.4 |

| All Cancer | ||||||||

| Total | na | 211.4 | na | na | na | 270.4 | 210.9 | 194.1 |

| White | na | 200.5 | na | na | na | 259.8 | 206.4 | 192.6 |

| Black/African American | na | 257.5 | na | na | na | 279.8 | 256.5 | 236.9 |

| Ischemic Stroke | ||||||||

| Total | na | 38.8 | na | na | na | 68.7 | 43.4 | 31.2 |

| White | na | 38.3 | na | na | na | 54.1 | 41.9 | 30.3 |

| Black/African American | na | 41.1 | na | na | na | 86.0 | 57.8 | 42.9 |

| Diabetes | ||||||||

| Total | na | 26.6 | na | na | na | 64.1 | 26.6 | 24.5 |

| Black/African American | na | 18.7 | na | na | na | 30.3 | 22.9 | 22.3 |

| Black | na | 58.5 | na | na | na | 99.7 | 57.8 | 47.6 |

| Infant Mortality | ||||||||

| Total | na | 7.9 | na | na | na | na | 7.8 | 6.7 |

| White | na | na | na | na | na | na | 6.4 | 5.7 |

| Black/African American | na | 11.6 | na | na | na | na | 7.8 | 13.3 |

General Notes: NA = not available; mil=million, Little Rock is located in Pulaski County; Marvell, Helena West Helena are located in Phillips County. Helena and West Helena were individual cities until they consolidated in 2006.

Notes on Demographic Characteristics: Total population figures for all geographic regions are from 2009. Other demographic data for counties, AR and US are also from 2009. Data for Little Rock are from 2006-08. Data for Marvell, Helena and West Helena are from 2000 (39)

Notes on Mortality Rates: Infant mortality rate per 1000 live births, 2003-05. All other rates are age-adjusted rates per 100,000 persons. All mortality rates are for 2007. Heart Disease = ICD-10 I60-I78; All Cancer = ICD-10 C00-D48; Ischemic Stroke= ICD-10 I64-I64 (40)

Although disparities and other challenges exist, assets also abound. Delta-bred people are resilient and resourceful, often overcoming seemingly insurmountable odds. The extended family structure and the small-church religious network support residents and local leadership development, and both unite local knowledge and experience that can be used to overcome barriers and survive a system not easily accessed by all. A perception by Delta-residents that no one is going to “do for us” has led to a sense of independence and determination that has prompted action. For example, when Marvell residents realized that they were lacking quality education and housing, they formed their own CBO, BGACDC, to address the issue. Recognizing gaps in healthcare access, Delta-based organizations formed MDCC to capture federal resources to support the development of rural health networks. TCRHN was subsequently established to target access issues in ways consistent with the extended family culture and small-church social networks.

Methods

Wallerstein’s CBPR Logic Model (9) provides the structure for documenting partnership capacity building activities. It focuses on CBPR processes and outcomes, and indicates how context and group dynamics affect interventions and consequently affect system, capacity and health-related outcomes, which can then circle back to affect context. In this model, context refers to factors affecting partnership formation, and the nature of the partnership and its activities. Group dynamics refers to factors affecting interactions between partners. Interventions are partnership activities undertaken to address identified problems. Finally, outcomes represent intermediate intervention results, including system and capacity changes, and improvements in health and health disparities (9) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

CBPR Logic Model

Source: Adapted from Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Tafoya G, Belone L, Rae R. What Predicts Outcomes in CBPR? In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 2008. p. 371-388.

Procedures

An iterative process was used to obtain data from representatives of organizational partners for model constructs and to develop this paper. Each construct was discussed by partners to determine what illustrative experiences would be described. A qualitative group decision process was used to prioritize data using the criteria that each partner’s participation would be represented, the breadth of activities and experiences would be reflected, and activities the group identified as being most crucial contributors to partnership outcomes would have higher priority for reporting. Each co-author wrote sections that were relevant to their experience, with the lead author incorporating sections and input from discussions into a final integrated piece.

Results

National/Local Policies, Trends, and Political Governance. Arkansas, U.S. used proceeds from the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement to establish the COPH in 2001 (13). Early COPH leaders committed to community-based public health (CBPH) principles established the OCBPH to develop community partnerships; to provide resources for the COPH and community partners regarding CBPH theories and methods; to assist in developing new community-based educational, service, and research programs; and to support development and implementation of CBPR projects (11). This commitment was supported by the rapid development, nationally, of health-related CBPR in the 1990’s and the increasing acceptance of, and funding for, this approach to research (14,15). The 2003 Institute of Medicine report on racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare (16) along with a growing body of research on social determinants of health (17,18) were also critical drivers and supports to these partnerships.

Historical Context of Collaboration. Community partners’ perceptions of UAMS prior to partnering with the COPH centered around individuals’ experiences with receiving healthcare at the University hospital and its clinics. These impressions varied. Some saw UAMS as a haven– a place for care for particularly serious problems. Others perceived UAMS as the “welfare hospital” where care might not be the best but where people went when they could not afford care elsewhere.

Strong and pre-existing relationships between COPH faculty and staff of two of the partnering CBOs provided a strong foundation for the partnerships between BGACDC, MDCC and the COPH. Other factors contributing to the early trust and understanding between partners include joint learning experiences and educational opportunities, and joint efforts to secure funding to support partner programs. For example, in 2001, a team of COPH and community partners visited the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill (UNC) and the University of Michigan (UM) to learn about their long-term efforts to integrate CBPH into their Public Health research, teaching, and practice. Partnership members also participated together in Undoing Racism Workshops (19,20), which created a common language for dialogue about issues of power, privilege, and institutionalized racism. These workshops, sponsored by the COPH and its institutional partners, were carried out by the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond with a focus on “understanding what racism is, where it comes from, how it functions, why it persists and how it can be undone..[using] a systemic approach that emphasizes learning from history, developing leadership, maintaining accountability to communities, creating networks, undoing internalized racial oppression and understanding the role of organizational gate keeping as a mechanism for perpetuating racism” (19). These shared activities, further described below, have established a common base of experience and expectations.

Community Capacity and Readiness. The community partners have strong roots and capacity for engagement within their communities, predating their partnership with the COPH. Their leaders have played significant community advocacy and organizing roles, such as serving on the local school board, chairing community development committees, and organizing local events.

BGACDC is a thirty-two year old CBO, serving residents of Marvell, Elaine and eight unincorporated communities, through its child and youth development, adult education, housing, health, and economic development programs. BGACDC emphasizes individual and organizational development and, as such, has sponsored staff and volunteers in training for leadership development, community and economic development, housing development, and organizational capacity-building. These efforts have succeeded in producing a number of high professional achievers, and in BGACDC becoming the county’s leading producer of new and remodeled housing. BGACDC was recognized for its efforts through the receipt by its director, Mrs. Beatrice Shelby, of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Community Leadership Award, and of the Ford Foundation Leadership for a Changing World Award, and through invitations to partner with the WK Kellogg Foundation (WKKF) Rural People / Rural Policy Initiative and the Marvell Nutrition Intervention Research Initiative (NIRI), among others (21).

MDCC was established in 2001 to increase resources for, and understanding of, partnerships to enhance and promote community-driven health improvement initiatives. Through its HRSA-funded ADRDN program, MDCC provides technical assistance and funds to Delta-based multi-county networks to develop and implement health programs. MDCC also administers Arkansas, U.S.’ only health-focused AmeriCorps program and served as a community partner and community fiscal agent for the USDA Marvell NIRI (22).

TCRHN is a grassroots CBO whose mission is to improve access to healthcare. TCRHN’s leadership, trained by the Kettering Foundation in the use of deliberative democracy forums, has used this approach to community engagement (CE) as an organizing tool. Its best-known program, the Community Connector Program (CCP), uses community health workers (CHW) to link residents to needed long-term care (LTC) services (23). The program was developed in response to community sentiment that, “we have great health resources in the Delta; but we don’t access them,” often because of lack of awareness or problems with trust in providers.

University Capacity and Readiness. In addition to having strong CBOs to partner with, the COPH has a number of internal structural supports for CBPR, including the OCBPH (described above) and its community liaisons, and the early opportunity to obtain education with partners about CBPH/CBPR through visits to UNC and UM. A combination of grants and core support to hire a part-time research assistant and to bring in academic and community consultants to assist with faculty development in CBPR and disparities also increased COPH partnering capacity. Other critical supporting structures have included monthly meetings between the OCBPH Director and the COPH Dean, a faculty committee designed to advise and connect the OCBPH with COPH departments, and core support for meetings focused on CBPH/CBPR and health disparities and for community partners to serve as co-instructors and guest lecturers in COPH courses. None of these assets would have been available had there not been strong leadership and support for the principles of CBPR from the COPH Dean and senior administrators.

OCBPH involvement in the Undoing Racism Workshops held at UAMS led to development of a workshop alumni group that met regularly to discuss potential opportunities and strategies for action and the need to organize those working on diversity issues at UAMS. The resulting cross-campus Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities Taskforce was influenced by several key publications (16,24,25) and subsequently identified three areas (quality of care, education, and faculty/student diversity) for UAMS to target to address racial and ethnic health and healthcare disparities in Arkansas, U.S.. In 2005, the Taskforce submitted a brief on its organization and purpose to the UAMS Chancellor, who subsequently asked the Taskforce to regularly report to him and to expand its membership to include representatives from all the Colleges and the Hospital. In addition, he charged the Taskforce with making recommendations for addressing language assistance services within UAMS clinical programs.

The Taskforce also served as a planning committee for a campus-wide retreat for addressing racial and ethnic health and healthcare disparities, which was sponsored by the COPH as a part of the WKKF’s Engaged Institutions Initiative. The Taskforce recently completed a campus-wide survey of students on the racial and ethnic diversity attitudes and climate at UAMS, the findings of which will form part of an audit (described below).

Another COPH structural asset is a subset of faculty with interest and skills in CBPH/CBPR. The top-down/bottom-up emphasis on CBPH in the COPH has resulted in an environment in which CBPR has become more mainstream, facilitating involvement of more traditional researchers in CBPR. Outsiders can bring skills and resources when they enter the community and can use such assets to strengthen the community’s power to serve their own needs (26). This kind of faculty capacity has played an important role in supporting community efforts (e.g. program evaluation and community research infrastructure development).

Perceived severity/salience of health issues. Health issues are of utmost concern to COPH community partners. Epidemiologic data indicate that citizens in the Arkansas Delta have the poorest health indicators and limited healthcare access. These statistics occur in a larger context of social determinants which create large racial and income disparities in health status (27). Against this background, COPH community partners have historically focused on addressing social determinants, disparities, and access to services.

Group dynamics

The group dynamics construct of Wallerstein’s model’s has three sub-dimensions: individual, structural, and relational dynamics of the partnerships.

Individual Dynamics. Partnership activities have been extremely important in creating individual “cultural humility and critical self-reflection” (9). Undoing Racism Workshops, which have been attended jointly by COPH and community partners, focus on increasing awareness of white privilege and how it operates at both the conscious and unconscious level to perpetuate oppression. Incorporation of this content into courses co-taught by COPH and community partners has reinforced integration of these concepts and reflection on how these dynamics play out in the everyday context of these partnerships. The use of the privilege walk (28) and other individual and group reflection exercises provide tools and content for explicit discussion of these issues among community partners, faculty, and students, and serve to increase self-awareness and understanding of these social determinants of health.

Structural dynamics

Formal/Informal Agreements. While partnerships were not established with formal written agreements, a number of commitments were made by the COPH, such as support of community liaisons. In some cases, the COPH has entered into subcontracts with partners for specific activities or grant-funded projects. Students are also required to develop Memoranda of Agreement with community partners for course-related projects.

Agreement on Values/Expectations. OCBPH strategic planning conducted in 2004 with community partners identified a shared interest in social justice, health equity, and social determinants of health. The joint experience participating in Undoing Racism Workshops and conducting over 20 community screenings and facilitated discussions of the Unnatural Causes documentary series (29) helped to solidify mutual understanding of institutionalized and historical aspects of oppression that perpetuate disparities. This four-hour documentary series of seven episodes was produced by California Newsreel in collaboration with public health experts and organizational partners including the National Minority Consortium, the Joint Center Health Policy Institute and the National Association of County and City Health Officials. This series takes on the challenge of communicating the root causes of socio-economic and racial inequities in health status and seeks to broaden public understanding of the role of social structural factors in these outcomes.

Allocation and Level of Resources Invested. The COPH has a long-term commitment to having community liaisons available to work with partners. Community liaisons help connect partners to resources and contacts, serve on boards, assist with planning, and provide trainings. One community partner serves as a paid co-instructor in required DrPH courses and other community partners have served as paid guest lecturers. The COPH has also helped partners to obtain grant funding (e.g. HRSA funds that supported MDCC’s establishment and RWJF funds supporting the CCP).

Community partners have also invested significant time, effort, and resources to participate in COPH-initiated activities such as site visits by funders, training and planning sessions, presentations, conferences, web and face-to-face meetings, events, and classes. Sometimes their efforts have been supported by honoraria and/or travel reimbursement, but many times they have not been, reflecting their commitment.

Relational dynamics

Congruence of Core Values and Mutual Respect. While the structures supporting these partnerships have been essential to their success, their impact would be extremely limited if not for the personal relationships and shared core values that exist. These values include recognition of the mutual benefit of partners with different expertise; the significance of grassroots voices; the importance of CBPR principles; and the need to address the injustice of disparities.

Dialogue/Mutual Learning. Joint participation in Undoing Racism Workshops helped create a common language to discuss difficult issues related to racism; increased recognition of institutional racism; and enhanced faculty understanding of how structures can benefit them while oppressing others. For example, prior to this training, some of the faculty involved were not fully aware of the under-representation of racial minorities on high-level decision-making bodies at UAMS or the day-to-day discrimination experienced by minority colleagues and community partners. Likewise, community partners talked about aspects of their communities or personal experiences they felt reflected their internalized oppression.

Having community partners participate as co-instructors or guest lecturers has provided a significant learning opportunity for partners and faculty involved throughout course development, annual updating and modification, and during class discussions. Community partners have become more knowledgeable about CBPR principles, program design, and evaluation methods. COPH faculty and students have learned about community power dynamics, the importance of history, the community’s mixed perceptions of academics and other outsiders trying to “help”, and experiences that established and deepened these impressions.

Leadership and Stewardship. Community partners have taken on significant local and national leadership roles over the course of the partnerships including serving on National Institutes of Health’s Council of Public Representatives, serving as the Deputy Co-Director of the Arkansas Prevention Research Center (APRC), and two being recipients of the RWJF Community Leadership Award. COPH liaisons also serve on the Boards of several partnering organizations.

Influence and Power Dynamics. Clearly, there are many times when traditional dynamics play out with professional knowledge, skills, and expertise having a stronger influence on choices made, issues raised, and projects that get discussed; but, there have also been instances where community preferences have driven final decisions. It has been important for the COPH, as the institutional partner, to avoid pushing partners to take on projects with which they are uncomfortable. For example, when faculty approached BGACDC to partner on a study on agricultural-related factors in air and water quality (which they had previously identified as of concern), there was significant resistance from BGACDC staff. They felt such a project could have negative repercussions for their organization and others in their community whose livelihood was dependent on the agricultural economy. As a result, the partnership did not pursue that study.

Researchers’ Community Involvement. COPH faculty and staff have participated in community events (e.g. MLK Day Marade, Arkansas Delta Green Expo); in locally-driven initiatives (e.g. ADRDN’s regional conference, Unnatural Causes documentary screenings, and Delta Bridge’s community development efforts (30)); in joint projects (e.g. Community Research Workshops and the CCP evaluation (both described below)); and in bringing visitors to the Delta to learn about the community and the community partners.

Participatory Decision-Making and Negotiation. Community partners developed a code of ethics for researchers who want to conduct research in their communities. A COPH student worked with partners using multiple deliberative forums to engage communities in discussions about having agreements on goals, data ownership, and dissemination of information. The final code includes the key concepts of shared power; equitable inclusion; mutual benefit; equal opportunity for capacity building; respect and recognition; and ongoing communication.

Integration of Community Beliefs. Community partners focus on engaging residents in identifying community assets and needs, implementing solutions that incorporate community experience and perspectives, and building on identified resources. TCRHN’s CCP was developed to respond to the need for trusted advocates with information about accessing existing services and builds on community interest in helping citizens access home and community-based LTC services and avoid unnecessary institutionalization (31,32).

Interventions

The “Interventions” construct considers whether interventions are designed, implemented, and researched to fit with community values and involve the community. A critical issue is sustainability.

Fits with Community Explanatory Models. While community explanatory models have not been explicitly studied within these partnerships, a core set of beliefs and values of the partners’ communities informs the approaches they use, including 1) trust is given to those who understand based on their own experience; 2) relationships should come first; and 3) priorities are based on need and on perceived relevance and possibility.

TCRHN’s CCP and MDCC’s Prescription Assistance Program (PAP) grew out of community-identified needs. These programs hire and train local individuals to meet those needs, in keeping with the critical role of community relationships and with their desire to build on existing assets. In the CCP, CHWs live in the community and share characteristics with those they serve. Key to their success is their ability to increase trust and provide valuable information about available services. They identify individuals in need through both formal methods (e.g. provider referrals) and through informal social networks.

Attends to Bi-directional Translation/Implementation/Dissemination. Many of the partnership interventions were developed in an iterative manner. For example, after TCRHN developed and implemented the CCP pilot, COPH provided technical assistance on evaluation, sustainability, and the need for evidence of cost impact.

Community partners have also provided critical input into COPH activities as consistent participants in site visits by agencies or foundations funding or evaluating the COPH, co-presenters in conferences, and preceptors and educators of students and faculty.

Appropriate Research Design. The CCP is an example where a quasi-experimental design was selected because random assignment of participants to the CCP intervention or a control condition was not possible. COPH faculty evaluating the CCP used propensity score matching in which CCP participants in intervention counties were matched to Medicaid beneficiaries residing in non-intervention counties to strengthen the design (31,32).

Outcomes

The outcomes construct has two sub-dimensions: 1) intermediate system and capacity changes, and 2) health and disparities outcomes.

Intermediate System and Capacity Changes. Partnership activities have led to several intermediate system and capacity changes. The increased financial stability and sustainability of these minority-controlled community organizations and their programs has increased their power within their communities and increased their ability to contribute to community empowerment and renewal. Their programs are aligned with the cultural values of those they serve and provide community models from which COPH students and faculty are learning. These relationships have also increased opportunities to fund infrastructure for community-based and translational research and have served as exemplars, speeding the pace of formation of other community partnerships (33).

An example of a system change resulting from these partnerships is the change in outreach methods used by Arkansas Medicaid to serve residents in need of LTC services. Prior to the CCP, residents in need of LTC primarily learned about LTC services by contacting service providers or state agencies. There was no direct LTC service outreach in the community. The COPH evaluated the TCRHN’s CCP three-county demonstration which used CHWs to canvas communities, identify elderly and adults with disabilities in need of LTC services, and then link them to services, particularly those available in the home or community. The evaluation showed the CCP generated a $2.92 savings to the Medicaid program for every $1 invested by reducing the use of institutional care and increasing the use of home and community-based LTC (32,34). These findings led Arkansas Medicaid to expand the program into 15 counties.

The capacity of UAMS, the COPH and the community partners has been enhanced due to these partnerships. In 2009, UAMS received NIH funding to establish a Translational Research Institute (TRI). COPH faculty play important roles in the TRI core units, particularly, the Community Engagement Component. The OCBPH and community partners have helped identify community priorities, serving on the TRI’s Community Advisory Board, and in obtaining additional NIH funding to build community capacity for CBPR by adapting the CCP model to increase minority participation in research. The COPH has also benefited from its community partnerships through CDC funding received in 2009 to establish the ARPRC, which focuses on using CBPR to reduce disparities in chronic disease. The COPH’s underlying CBPH philosophy and experience with community partners guided the development of the ARPRC’s organizational structure, which is unique among PRCs across the US in having both community and academic Center Deputy Directors and community and academic Co-Directors for core units. Community Co-Directors are paid a stipend for carrying out their leadership roles. The ARPRC will be providing workshops to increase academic and community capacity to conduct CBPR. It also provides a rich community-based service learning environment for COPH doctoral students.

Community partners have increased their knowledge of CBPR and the research process through partnership with the COPH. Community and academic representatives involved in the USDA NIRI agreed that community members involved would benefit from knowing more about the research process and research ethics. The USDA retained the OCBPH to develop a workshop, which they did with input from community partners, who helped ensure the workshop content was appropriate and formatted in a way to be most accessible to community members (35). The evaluation of the workshop showed a positive trend in improvements in CBPR-related attitudes and behavior (36).

Students and partners have also increased their understanding of racial and ethnic health disparities through participation as Shepherd Poverty Center and UA Clinton School of Public Service interns, and through the Arkansas Health Disparities Service Learning Collaborative. This collaborative was developed as a result of participation in the Engaged Institutions Initiative (described above), which supported development and implementation of an interdisciplinary Masters-level service learning course on racial and ethnic health and healthcare disparities, with an emphasis on historical and social determinants and strategies for elimination, combined with community-based practice and reflection (37). In addition, community partners assisted in piloting a community-based workshop for individuals and CBOs to increase awareness about the social determinants of health and racial health disparities; to increase community action with respect to health disparities; and to increase community understanding and participation as service learning sites for students. This workshop prompted a Little Rock-based CBO, in partnership with residents of a low-income neighborhood, to establish a Healthy Communities initiative, which focuses on community gardening, healthy eating, energy efficient housing, the role of community ecosystems in sustainability, and environmental justice.

Health and Disparities Outcomes. Quantitative data are not available to determine whether these partnerships have led to improved health outcomes. However, several of the partnership programs are clearly affecting process measures associated with better outcomes such as improved access to home and community-based LTC services (TCRHN’s CCP) and increased access to prescription medications (MDCC’s PAP). MDCC’s PAP has helped 9,228 Delta residents access free or low-cost prescription medications, saving them a total of $5 million in prescription medication costs for drugs needed largely to manage chronic diseases such as diabetes, high cholesterol, and hypertension. These programs are likely affecting racial and economic disparities in access as well, since those experiencing these disparities are targeted.

Table 2 summarizes partner involvement in various activities to illustrate the long-term, collaborative nature of the partnerships.

Table 2.

Summary of Activities, Programs, and Centers, and Partners Involved

| Activities, Programs, and Centers | Partners Involved | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timeframe | UAMSa | COPHb | OCBPH | MDCC | BGACDC | TCRHN | |

| Trip to UNC and UM | 2001 | X | X | X | |||

| MDCC Arkansas Delta Rural Development Network | 2001-present | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| OCBPH established | 2002 | X | X | X | X | ||

| TCRHN Community Connector Program | 2003- present | X | X | X | X | ||

| Undoing Racism Workshops | 2003-2007 | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Deliberative Community Forums | 2003-present | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MDCC AmeriCorps/ VISTA Prescription Assistance Program | 2004-present | X | X | X | X | X | |

| UAMS Health Disparities Taskforce | 2004-present | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Co-Teaching | 2005-present | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Shepherd Poverty Center and UA Clinton School Interns | 2005-present | X | X | X | X | ||

| USDA NIRI Community Research Workshops | 2006-2008 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| WK Kellogg Engaged Institutions Init | 2006-2007 | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| WK Kellogg Rural People / Rural Policy Initiative | 2006-2010 | X | X | X | |||

| CNCS/CCPH AR Health Disparities Service Learning Collaborative | 2007-2010 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Unnatural Causes Screenings | 2008-present | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| AR Prevention Research Center | 2009-present | X | X | X | X | ||

| Center for Clinical and Translational Research | 2009-present | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Arkansas Delta Green Expo | 2010 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Community Linked Research Infrastructure | 2010-present | X | X | X | X | ||

UAMS is selected if entities other than the COPH have been involved.

COPH is selected if other than OCBPH faculty/staff have been involved.

Changes in context

University Capacity & Readiness. Another important feature of the model is its allowance for outcomes to loop back around to affect context. The experiences of these partnerships has affected the capacity of both community and university partners to engage in research. This is exhibited by successes of these partnerships and by the role community partners are playing in building the capacity of newer COPH community partners.

The University context has also been affected as the COPH has increased its capacity and understanding of issues related to diversity and health disparities and played a key role in the UAMS Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities Taskforce. The UAMS Center for Diversity Affairs (CDA) was recently re-organized with promotion of its director to Assistant Vice-Chancellor and giving it a cross-campus purview. The University also has a new Chancellor who supports centralized coordination through the CDA of campus diversity efforts (including those of the Taskforce) and implementation of an audit to better define and create momentum to address these issues.

Conclusion

This partnership “story” illuminates several important lessons for the development and maintenance of academic-community partners.

First, both academic and community partners need capacity building to engage in CBPR work. Both “sides” of the partnership, particularly the academics, may perceive themselves as being adequately knowledgeable of pressing public health problems and methods to address them. However, the experience of these partnerships reveals that all participants benefited from shared experiences and learning opportunities that were important for establishing a common base of experience and expectations as well as establishing a common language for discussing difficult issues.

Second, the development of a small core group of academics and community partners interested in CBPR was important for expanding its adoption more widely, both in the academic institution and in the community. Consistent with notions of Diffusion Theory (38), early adopters of CBPR were able to share their experience and knowledge which led to others at UAMS choosing to use this approach to research.

Finally, continuing to engage in individual and joint capacity building activities, even when there was no active CBPR project, enabled the partners to be poised to leverage past work and take advantage of emerging opportunities. Many CBPR partnerships may come together around a specific study and disband when the study ends. However, by continuing a strong bi-directional relationship, even in the absence of a current CBPR study, these partners were able to rapidly respond to new challenges and funding announcements.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided in part by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Translational Research Institute (TRI) (National Center for Research Resources Award No. 1UL1RR029884) and TRI career development award (KL2RR029883). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health. Support for the Community Connector Program was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Enterprise Corporation of the Delta, the Arkansas Department of Human Services, the Foundation for the Mid-South, and the MDCC. MDCC is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Corporation for National and Community Services, Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, and other local contributors.

References

- 1.Barker D. The Scholarship of Engagement: A Taxonomy of Five Emerging Practices. J Higher Educ Outreach Engage. 2004;9(2):123–37. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Community-Campus Partnerships for Health Community-based participatory research: policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2001;14(2):182–97. doi: 10.1080/13576280110051055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scutchfield FD, Ireson C, Hall L. The voice of the public in public health policy and planning: the role of public judgment. J Public Health Policy. 2004;25(2):197–205. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3190018. discussion 206-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Downey LH, Anyaegbunam C, Scutchfield FD. Dialogue to deliberation: expanding the empowerment education model. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33(1):26–36. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.33.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farquhar SA, Wing S. Methodological and ethical considerations in community-driven environmental jJustice research: Two case studies from rural North Carolina. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. 2nd ed Jossey Bass; San Francisco: 2008. pp. 263–83. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tau Lee P, Krause N, Goetchius C, Agriesti JM, Baker R. Participatory action research with hotel room cleaners in San Francisco and Las Vegas: From collaborative study to the bargaining table. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. 2nd ed Jossey Bass; San Francisco: 2008. pp. 335–53. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S40–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed SM, Palermo AG. Community engagement in research: frameworks for education and peer review. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1380–1387. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Tafoya G, Belone L, Rae R. What predicts outcomes in CBPR? In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. 2nd ed Jossey Bass; San Francisco: 2008. pp. 371–88. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Community-Based Public Health Caucus [Accessed 11/13, 2010];CBPH Caucus Vision Statement. Available at: http://www.sph.umich.edu/cbphcaucus/vision.html#.

- 11.Felix H, Stewart MK, Raczynski JM, Bruce TA, From the schools of public health Building a college of public health: structuring policies to promote community-based public health. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(2):225–227. [Google Scholar]

- 12.University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences [Accessed 9/1, 2010];Website. Available at: http://www.uamshealth.com/why-uams/

- 13.Thompson JW, Boozman FW, Tyson S, Ryan KW, McCarthy S, Scott R, et al. Improving health with tobacco dollars from the MSA: the Arkansas experience. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23(1):177–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruce TA, McKane SU, editors. Community-based public health: A partnership model. American Public Health Association; Washington DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. 2nd ed Jossey Bass; San Francisco: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Natl Acad Press; Washington, DC: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LaVeist TA, editor. A public health reader. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2002. Race, ethnicity, and health. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995:80–94. Spec No. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Peoples’ Institute for Survival and Beyond [Accessed 2/12/12];Undoing Racism Community Organizing Workshops. Available at: http://www.pisab.org/

- 20.Aronson RE, Yonas MA, Jones N, Coad NE. E. Undoing racism training as a foundation for team building in CBPR. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. 2nd ed Jossey Bass; San Francisco: 2008. pp. 447–51. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arkansas Citizens First Congress [Accessed 10/20, 2010];Arkansas Citizens First Congress homepage. Available at: http://citizensfirst.org/about-us.

- 22.United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service [Accessed 11/13, 2010];Delta Obesity Prevention Research Program. Available at: http://www.ars.usda.gov/research/projects/projects.htm?accn_no=413503.

- 23.Felix HC, Stewart MK, Mays GP, Cottoms N, Olson MK, Sanderson H. Linking residents to long-term care services: first-year findings from the community connector program evaluation. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2007;1(4):311–9. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nash C, Ochoa E. Arkansas racial and ethnic health disparity study report. Arkansas Minority Health Commission; Little Rock, AR: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Sullivan Commission . A report of the Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce. Sullivan Commission; 2004. Missing persons: Minorities in the health professions. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKnight JL. Rationale for a community approach to health. In: Bruce TA, McKane US, editors. Improvement community-based public health: A partnership model. American Public Health Association; Washington, DC: 2000. pp. 13–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hotez PJ. Neglected infections of poverty in the United States of America. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(6):e256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. [Accessed 12/18, 2010];Privilege Walk, from Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice. Available at: http://www.life.arizona.edu/residentassistants/programming/social_justice/PRIVILEGE_WALK.pdf.

- 29.California Newsreel I. California Newsreel, Inc [Accessed 12/18, 2010];Unnatural Causes: Is Inequality Making us Sick? Available at: http://www.unnaturalcauses.org/

- 30.Delta Bridge Project [Accessed 10/31, 2010]; Available at: http://deltabridgeproject.com.

- 31.Mays GP, Felix HC. Economic evaluation of the Arkansas Community Connector Program: Final report of findings from the Demonstration and Extension Periods. Arkansas DepartmentHuman Services; Little Rock, AR: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Felix HC, Mays GP, Stewart MK, Cottoms N, Olson M. Medicaid savings resulted when community health workers matched those with needs to home and community care. Health Affairs. 2011;30(7):1366. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clayton PH, Bringle RG, Senor B, Huq J, Morrison M. Differentiating and assessing relationships in service-learning and civic engagement: Exploitative, transactional, or transformational. Michigan J Commun Serv Learning. 2010;16(2):5–22. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Using Community Health Workers to Target Home and Community-Based Long-Term Care: A Propensity Score Analysis of Economic Impact. Oral Presentation at the 2010 Annual Meeting of AcademyHealth; Boston, MA. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewart MK, Colley D, Huff A. Participatory Development and Implementation of a Community Research Workshop: Experiences from a community-based participatory research partnership. Commun Health Partnerships. 2009;3(2):165–178. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart MK, Colley D, Felix H, Huff A, Shelby B, Strickland E, et al. Evaluation of a workshop to improve community involvement incommunity-based participatory research efforts. Educ Health. 2009;22(3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Development and Early Experience with a Masters Level Public Health Service Learning Course on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Oral Presentation at the 2010 Annual Conference of Community Campus Partnerships for Health; Portland, Oregon. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovation. 5th ed Free Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.US Census [Accessed 11/13, 2010]; Available at: http://www.census.gov.

- 40.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed 11/13, 2010]; Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov.