Abstract

Herein we have demonstrated that both superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimic, cationic Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(N-n-hexylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin (MnTnHex-2-PyP5+), and non-SOD mimic, anionic Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(4-carboxylatophenyl)porphyrin (MnTBAP3−), protect against oxidative stress caused by spinal cord ischemia/reperfusion via suppression of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pro-inflammatory pathways. Earlier reports showed that Mn(III) N -alkylpyridylporphyrins were able to prevent the DNA binding of NF-κB in an aqueous system, whereas MnTBAP3− was not. Here, for the first time, in a complex in vivo system—animal model of spinal cord injury—a similar impact of MnTBAP3−, at a dose identical to that of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, was demonstrated in NF-κB downregulation. Rats were treated subcutaneously at 1.5 mg/kg starting at 30 min before ischemia/reperfusion, and then every 12 h afterward for either 48 h or 7 days. The anti-inflammatory effects of both Mn porphyrins (MnPs) were demonstrated in the spinal cord tissue at both 48 h and 7 days. The down-regulation of NF-κ B, a major pro-inflammatory signaling protein regulating astrocyte activation, was detected and found to correlate well with the suppression of astrogliosis (as glial fibrillary acidic protein) by both MnPs. The markers of oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation and protein carbonyl formation, were significantly reduced by MnPs. The favorable impact of both MnPs on motor neurons (Tarlov score and inclined plane test) was assessed. No major changes in glutathione peroxidase- and SOD-like activities were demonstrated, which implies that none of the MnPs acted as SOD mimic. Increasing amount of data on the reactivity of MnTBAP3− with reactive nitrogen species (RNS) (·NO/HNO/ONOO−) suggests that RNS/MnTBAP3−-driven modification of NF-κB protein cysteines may be involved in its therapeutic effects. This differs from the therapeutic efficacy of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ which presumably occurs via reactive oxygen species and relates to NF-κB thiol oxidation; the role of RNS cannot be excluded.

Keywords: superoxide dismutase mimetics, ischemia reperfusion, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, MnTBAP3−, oxidative stress, NF-kappa B

Introduction

Spinal cord injury

The spinal cord is extremely vulnerable to ischemic injury. The descending thoracic or thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm surgery may cause spinal cord ischemia because of aortic cross-clamping, and can lead to severe neurologic complications including paraplegia and paraparesis [1,2]. The incidence of paraplegia and paraparesis still ranges from 5 to 35% [2]. Several strategies have been used clinically and experimentally to prevent paraplegia due to the spinal cord ischemia, and have included the use of shunts, systemic hypothermia, spinal fluid drainage, and infusion of scavengers of reactive species [3,4]. However, none of these have thus far been successful in preventing this unpredictable complication.

Cross-clamping of abdominal aorta for extended intervals of 30–60 min leads to low flow state and results, therefore, in irreversible spinal cord neuronal damage and loss of neurologic function. Such scenario is consistent with the anatomy of the spinal vasculature. The spinal cord receives a major portion of nutritive perfusion from the segmental radicular arteries arising from the descending aorta and from the largest segmental medullary artery—known as “artery of Adamkiewicz.” This artery provides a significant flow into the anterior spinal artery at the lumbosacral enlargement of the spinal cord. The nerves which supply the lower limbs originate from the lumbar enlargement. The magnitude of the insult to spinal function will be affected by the factors that impact the perfusion through the collateral circulation. The period of ischemia is followed by reperfusion when the major oxidative damage occurs. The reactive oxygen and nitrogen species produced during reperfusion induce lipid peroxidation and neuronal cell death in the spinal cord. These species also induce upregulation of pro-inflammatory pathways, including nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), which amplify primary oxidative stress and thus contribute to the ischemic injury. Prevention of oxidative stress-induced damage has thus the potential to reduce the spinal cord ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury [5,6].

Therapeutic effects of Mn(III) porphyrins in central nervous system injuries

Mn porphyrin (MnP)-based superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimics exhibit remarkable therapeutic effects in diseases which have oxidative stress in common, including injuries of central nervous system (CNS). Several recent reviews have summarized those effects [7–14]. While the favorable effects of cationic N-substituted pyridylporphyrins, such as Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(N-n-hexylpyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin (MnTnHex-2-PyP5+), are expected, those of anionic Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(4-carboxylatophenyl) porphyrin (MnTBAP3−) are far from understood. MnTBAP3−, anionic Mn porphyrin, has no SOD-like activity; its therapeutic effects have often been erroneously assigned to its SOD-like activity, and in particular mitochondrial MnSOD-like activity [15–36]. Even a redox-inert Zn analog, ZnTBAP4−, was claimed to have SOD-like activity [34]. In addition, MnTBAP3− has no significant catalase-like activity (Table I) [37]. Cationic MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, though, is a potent SOD mimic (Table I) [12,38–55]. Here we used a rat spinal cord injury model to test these two MnPs of vastly different thermodynamics and kinetics with regards to reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, with the goal to further our understanding of the origin of their therapeutic efficacy.

Table I.

Rate constants for the reaction of MnPs with different reactive species.

| MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ | MnTBAP3− | SOD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1/2 (mV vs NHE) | +314a | − 194b | ~+300c |

| log kcat (O2·−) | 7.48a | 3.16b | 8.64–9.20c |

| logkcat (H2O2-CAT) | ~1.6d | 1.1d | 1.1e |

| log k(·NO) | ~6f | NRg | h |

| log kred(O2) | 4i | NR | − 0.36j |

| log v0(HA−) | 1.7k | NR | ND |

| log kcat(H2O2-GPx) | ~4d | NR | l |

|

| |||

| log kred(ONOO−) | 7.11m | 5.02m | 3.97c |

| log kred(CO3·−) | 9.38m | 9.54m | n |

| log k(HNO) | ~4o | ~5p | ~6q |

For comparison, the values for SOD enzymes are also listed. Mn(III) N-substituted pyridylporphyrins have thermodynamics and kinetics of the Mn site similar to those of SOD enzymes. In turn, both undergo same reactions. Yet, sterical factors are entirely different precluding high reactivity of SOD metal site with species other than O2·−. The reactions which occur with high rate constants and may, therefore, be in common with the actions of those MnPs are grouped in red.

NR, not reactive; N/A, not applicable; ND, not determined

Ref [91];

Ref [57];

Ref [37] and Maia et al. SFRBM Meeting 2014, submitted;

Ref [123];

the rate constant of the reactivity of MnIITnHex-2-PyP4+ with · NO is estimated based on the reactivity of MnIITE-2-PyP4+ with · NO [124]. This reactivity is biologically relevant as cationic Mn(III) N-alkylpyridylporphyrins get readily reduced with cellular reductans, such as ascorbate due to its abundance within cell at milimolar levels. The rate constant for the reaction of MnIIIP with ·NO is low and estimated based on the reactivity of MnIIITE-2-PyP5+ to be log k(·NO) =−3.70 [124];

in its Mn + 3 oxidation state, MnTBAP3− is not reactive to ·NO unless ligand binding, such as urate, occurs prior to reduction and modifies its reduction potential;

relates to CuZnSOD and only when the metal, that is, Cu is in + 1 oxidation state [125];

relates to the reaction of reduced MnIIP with oxygen, O2, wich leads to the production of superoxide and subsequently peroxide and is of critical importance in the chemistry/biology of Mn(III) N-alkylpyridylporphyrins. Once in cell, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ is reduced to Mn + 2 oxidation state with cellular reductants. MnTBAP3− cannot be reduced to Mn + 2 oxidation state with cellular reductants to cycle with oxygen; yet once reduced with stronger reductant (such as sodium dithionite), it would favor reoxidation more than electron-deficient MnPs. Based on the data from Doctorovich’s group [126], it can undergo reduction to Mn + 2 oxidation state while binding HNO;

the high reactivity of MnPs with cellular reductant, ascorbate, plays an important role in the biology of Mn(III) N-substituted pyridylporphyrins [12,129,130]. v0 relates to initial rate, MnTBAP3− is non-reactive toward ascorbate. HA− is a monodeprotonated ascorbate which is a main species at physiological pH.

At low H2O2 levels, Cu in CuZnSOD gets reduced and produces ·OH bound to metal site, acting as peroxidase; at high H2O2 levels, SOD undergoes oxidative degradation [131,132].

Ref [133];

Ref [134];

Estimated based on the data on MnTE-2-PyP5+ and the similar redox properties and reactivities of these two MnPs with O2·−and ONOO−—it relates to the reaction of MnP with either Angeli’s salt or toluene sulfohydroxamic acid;

[126] relates to the reaction of MnP with HNO;

relates to CuZnSOD [135].

Some of the therapeutic effects of MnPs are listed below and in Figure 1. Melov et al. demonstrated the impact of MnTBAP3− on prolonged survival and lower systemic pathology of MnSOD knockout SODtm1Cje(−/−) mice. A prolonged survival was assigned to mimicking mitochondrial MnSOD [56]. Yet mice developed the pathology, including pronounced movement disorder progressing to total debilitation by 3 weeks of age, which was ascribed to the inability of MnTBAP3− to cross blood–brain barrier. Its anionic charge would most likely diminish its ability to cross any other anionic phospholipid-based membranes, including mitochondrial membranes. The Mn aqua/hydroxo/acetato complexes, common impurities in MnTBAP3− preparations [57,58], might have contributed to the brain toxicity related to manganism, due to prolonged treatment of young animals (starting at day 3 of age) at a dose of 5 mg/kg/day [59–61]. Danxia Liu’s group has used MnTBAP3− for years in a rodent spinal cord contusion injury model and has assigned its therapeutic efficacy to the scavanging of either ONOO− or broad spectrum of reactive species, including superoxide, H2O2, and ·OH radical [62,63]. Aladag et al. discussed the efficay of MnTBAP3− in rat subarachnoid hemorrhage model with regards to its SOD-like activity [64]. Rarely, the lack of therapeutic effect of MnTBAP3− was reported [31,65,66]. Mn(III) N,N′-diethylimidazolylporphyrin, MnTDE-2-ImP5+ (AEOL10150), was efficacious in a spinal cord compression injury when administered intrathecally as a single injection at 5-min post-reperfusion [67]. The intravenous (iv) administration was inefficacious [67]. MnTDE-2-ImP5+ has thermodynamics and kinetics similar to MnTE-2-PyP5+, but is bulkier and in turn has different bioavailability. In the same model, MnTE-2-PyP5+ was protective even when given iv as a single dose of 8 mg/kg at 15 min after spinal cord compression. Neurologic assessment at day 21 post-injury (rotarod with fixed and accelerated speed of rotation, coarse and fine screen upside down) demonstrated ~30% reduction in neurologic injury. Histological assessment, performed as reported [67], indicated that vehicle (non-injured) versus MnP-treated group scored 28 versus 21 (Batinic-Haberle et al., unpublished). In a traumatic spinal cord injury, a Fe(III) porphyrin with pyridylbenzoates in porphyrin meso positions (WW-85) suppressed inflammation and recovered limb function; the effects were ascribed to ONOO−-related chemistry/biology [68].

Figure 1.

Therapeutic effects of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ [12,38–55] and MnTBAP3− [20,35,63,64,70–90]. Structure of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and references related to reported studies are shown in blue in left circle. The structure of MnTBAP3− and its references are shown in red color in right circle. The central oval lists the same type of animal and cellular studies where both compounds are studied independently. The smallest circle lists the same type of studies where MnTnHex-2-PyP5+; was efficacious (blue references), but MnTBAP3− (red reference) was not. There is no single animal study with direct comparison of these two compounds. Both MnPs were only tested side-by-side in cellular studies: aerobic growth of SOD-deficient eukaryotic S. cerevisiae and prokaryotic E. coli [51,91,92].

MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and MnTBAP3− were directly compared only with respect to the aerobic growth of single-cell SOD-deficient organisms, Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae: while former was fully efficacious at as low as 0.3–10 μM, MnTBAP3− was not protective at up to 200 μM [51]. No single animal study explored those two compounds. When the data from two separate studies are compared, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ appears to be 100-fold more efficacious than MnTBAP3− in blocking the development of rat morphine antinociceptive tolerance [36,69]. In another carrageenan-induced rat paw inflammation study, a similar analog, Mn(III) N-ethylpyridylporphyrin (MnTE-2-PyP5+), was ~1.5 log units more efficacious than MnTBAP3−. The lower efficacy of MnTBAP3− relative to MnTE-2-PyP5+ was attributed to ~2.5 log units lower ONOO− reducing ability [69].

Several Mn(III)-substituted N-pyridyl- or N,N′-diimidazolylporphyrins suppress inflammation caused by I/R insult via suppression of NF-κB pro-inflammatory pathways [50,93,94]. The master transcription factor, NF-κB, controls antiapoptotic and anti-inflammatory pathways involved in CNS injuries [95–98]. The data on the involvement of SOD mimics in the oxidation of NF-κB thiol via H2O2/GSH [99,100] and/or HNO/NO/H2S reactions [101–103] made us decide to explore whether NF-κB is a common pathway in suppression of rat spinal cord I/R injury by MnTBAP3− and MnTnHex-2-PyP5+.

Materials and methods

A total of 52 female Spraque-Dawley rats weighing between 200 and 250 g were obtained from Rijeka University’s Laboratory Animals. Two rats died during this study because of surgical complications. None of them had any neurological disorder prior to surgery. All work described in this study was performed according to the protocols approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Rijeka.

Spinal cord injury procedure and study design

Rats were housed two per cage, exposed to a 12-h light/dark cycle, and had a free access to food and water. Animals were anesthetized with intraperitoneal (ip) injections of ketamine hydrochloride (0.1 mg/g body weight) and xylazine hydrochloride (0.02 mg/g body weight). The ip injection of cephalosporin (10 mg/kg) was administered prior to skin incision. Postoperative analgesia was provided with tramadol for 12 h; 150 U/kg of heparin was administered subcutaneously to all animals immediately before the procedure.

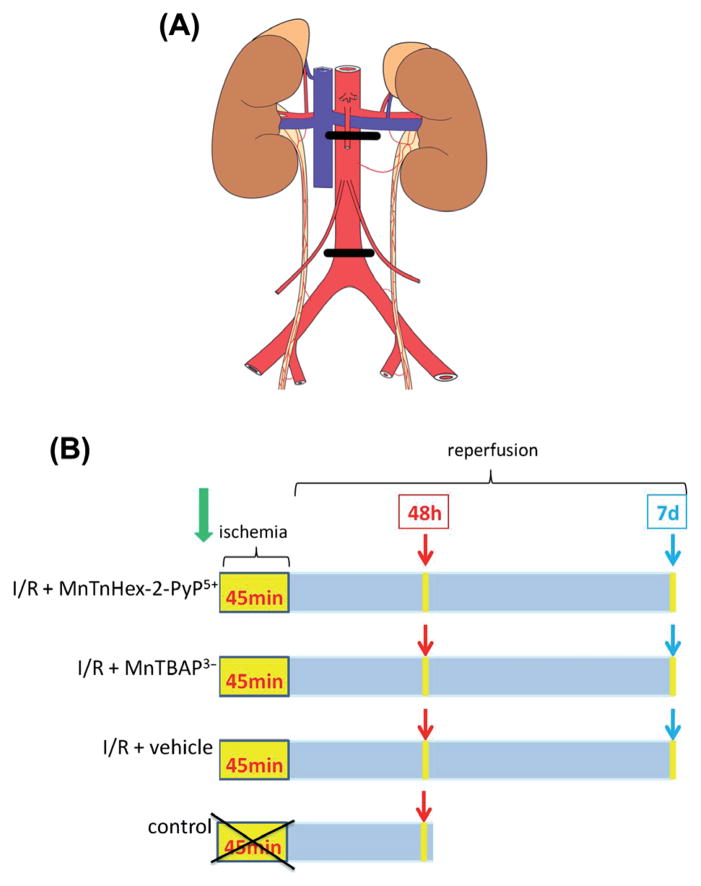

After the surface cleaning of the surgical area, a mid-line incision was made. The abdominal aorta was explored through transperitoneal approach. The intestines were exteriorized and wrapped in wet gauze. I/R injury of the spinal cord was induced by the occlusion of abdominal aorta. Abdominal aorta was clamped for 45 min with a proximal (just below the left renal artery) and a distal (just above the aortic bifurcation) clip as illustrated in Figure 2A. At the end of the surgery, the anterior abdominal wall was sutured using 5/0 polypropylene suture.

Figure 2.

The illustration of the aorta clamping positions (A) and study design schedule (B). (A) I/R injury of the spinal cord was induced by the occlusion of abdominal aorta. Abdominal aorta was clamped for 45 min with a proximal (just below the left renal artery) and a distal (just above the aortic bifurcation) clip; (B) rats in I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, I/R + MnTBAP3−, and I/R + vehicle groups underwent 45 min of spinal cord ischemia. The treatment started 30 min prior to ischemia and continued every 12 h until 48 h or 7 days. Rats from control (sham) group did not have I/R injury. They were sacrificed at 48-h post-sham procedure.

The animals were randomly divided into four groups: (1) I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ group, in which subcutaneous (sc) injection of 1.5 mg/kg MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ was given 30 min before I/R, followed by ischemia and reperfusion (n = 16); (2) I/R + MnTBAP3− group, in which sc injection of 1.5 mg/kg MnTBAP3− was given 30 min before I/R, followed by ischemia and reperfusion (n = 16); (3) I/R + vehicle group, in which the aorta was occluded for 45 min followed by 48 h or 7 days of reperfusion (n = 16); (4) control—the sham group, which included animals subjected to anesthesia and laparotomy without ischemia (n = 4) and was analyzed at 48 h after surgical procedure. The study design schedule is illustrated in Figure 2B. Drugs were administrated 30 min before surgical procedure, timing of which is relevant to thoracic surgeries. After closing the abdominal wall, drug administration continued every 12 h either for duration of 48 h or 7 days.

The first three groups consisted of two subgroups based on time post-reperfusion. One subgroup was sacrificed after 48 h and another subgroup was sacrificed after 7 days post-reperfusion. At either 48-h or 7-day post-reperfusion, half of the animals per subgroup were anesthetized with xylazine hydrochloride and ketamine hydrochloride, perfused transcardially with 0.9% saline and 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4), and sacrificed. The L3–S1 segments of the spinal cord were extracted. The tissue was fixed in 4% PFA for 24 h and embedded in paraffin wax for immunofluorescence investigation. Another half of each subgroup was not perfused with PFA. Their spinal cord was immediately immersed in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for spectrophotometry (thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), protein carbonyls, and enzymes) and Western blot analyses (protein carbonyls).

Motor assessment of spinal cord injury

Post-ischemic motor dysfunction was assessed every 24 h after reperfusion. A trained observer who was blinded to the group of animals evaluated the hindlimb motor function using Tarlov score and inclined plane test. Tarlov scale evaluated the animals as follows: grade 0, paraplegic with no evident lower extremity motor function; grade 1, poor lower extremity motor function, weak antigravity movement only; grade 2, moderate lower extremity function with good antigravity strength but inability to pull legs under the body; grade 3, able to stand but unable to walk normally; grade 4, minimal hopping; and grade 5 complete recovery and normal gait/hopping. In addition, animals were tested for their ability to stand on an inclined plane while facing upward at angles of 35°, 45°, and 50° angle; scores (0–3) were assigned for each inclination relative to pre-injury performance and then averaged for inclusion into the composite score. A composite neuromotor score (0–8) was generated by combining the scores for each of these tests, with a score of 8 indicating maximal motor function.

Sample preparation

Spinal cord tissue was weighted and homogenized in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4). The homogenates were aliquoted (100 μL) and used for lipid peroxidation and protein carbonyl content assessment. Remaining homogenate was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 min and the obtained supernatant was used as a source for enzyme assay. Supernatant was aliquoted and stored at −20°C to measure SOD and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activities. All procedures were performed at 4°C.

Lipid peroxidation assay

Lipid peroxidation was determined spectrophotometrically by measuring the levels of TBARS, using a modification of the method described by Ohkawa et al. [104]. Malondialdehyde (MDA) was used as an external standard.

Protein oxidation assay

Protein oxidation was determined using the OxyBlot™ kit, according to the manufacturer ’ s instructions. The method is based on immunochemical detection of protein carbonyl groups derivatized using 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH). Briefly, spinal cord samples were reacted with DNPH and the samples were electrophoresed and electrotransfered to nitrocellulose membranes. Subsequently, the primary rabbit anti-DNP antibody (1:150) and horse-radish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:300) were applied to detect protein carbonyl groups. Membranes were visualized by chemiluminescence using the Pierce SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The bands were recorded using the Kodak Image Station CF 440 and the densitometric analyses of the proteins of all molecular weights were done using the Kodak 1D 3.5 imaging software (Eastman Kodak, Inc., Rochester, NY, USA).

Enzyme assays

SOD activity was determined using the method that employs xanthine and xanthine oxidase to generate O2·−. The O2− was in turn reacted with 2-iodophenyl-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-phenyltetrazolium chloride, to form a red formazan dye whose absorbance at 505 nm was detected. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the quantity of SOD required to cause a 50% inhibition of the absorbance change per minute of the blank reaction. GPx activity was measured according to the Paglia and Valentine method [105]. GPx catalyzes the reduction of cumene hydroperoxide using glutathione as a reducing agent. Oxidized glutathione was reduced with NADPH (β-nicotin-amide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, reduced) in the presence of glutathione reductase, whereby NADPH was oxidized to NADP+. Oxidation of NADPH is monitored as decrease in the absorbance at 340 nm, whose rate was directly proportional to the sample’s GPx activity.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Immunofluorescence staining of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and NF-κB was done on 3-μm-thick formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded spinal cord tissue sections. Following deparaffinization, the antigen retrieval was performed using citric acid (pH 6.6) for 15 min in water bath at 95°C. The sections were then rinsed under fluent water for next 15 min. Non-specific binding sites were blocked using 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). In the subsequent step, the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies: anti-NF-κB p65 antibody—ChIP Grade (1:100, ab7970, Abcam) and purified mouse anti-GFAP monoclonal antibody (1:100, cat. no. 556328, BD Pharmingen). Incubation with secondary antibodies, Alexa fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000, Invitrogen) for NF-κB and Alexa fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (1:1000, Invitrogen) for GFAP, were applied for 1 h at RT. The sections were washed using PBS 3 ×5 min after each step. After being coverslipped in fluorescence mounting media, the signal was detected by fluorescence microscopy using an Olympus microscope BX51/BX52 (Tokyo, Japan). Images of the spinal cord ventral gray matter were analyzed by ImageJ software (NIH, USA). Positive cells were counted per mm2. The spinal cord tissues from four animals of the same study subgroup were analyzed. From each sample, three serial cross sections were obtained and on each four fields of 280 ×280 μm area were analyzed.

MnPs

A pure MnTBAP3−, synthesized and characterized as reported [57], was used in this study. It is fairly difficult to prepare the MnTBAP3− of high purity, especially to eliminate all low moleclar weight Mn(II)-related impurities [57]. The compound of same purity was used in reported animal model study [58]. It was also used in all studies related to E. coli and S. cerevisiae [51]. MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ of highest purity was synthesized and characterized by us as reported [106], and used herein and in all our earlier studies. This compound is presently in pre-clinical development and has been tested in non-human primate model of pulmonary radioprotection [41]. The doses selected here were in the range of doses used in reported studies. Aqueous solutions of 5.26 mM MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and 5.88 mM MnTBAP3− were used for rat sc injections.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistica software version 8.0 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). TBARS levels were expressed as nmol MDA/mg protein. SOD and GPx activities were expressed in U/mg protein. In densitometric analyses of protein carbonyl levels, the values were expressed as relative optical densities of the related bands. Area of astrocytes’ perikarya and the intensity of GFAP and NF-κB staining were expressed as number of positive cells/mm2. Statistical significance for the biochemical analyses data was calculated according to the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Duncan’s multiple range post-hoc test. For the GFAP and NF-κB staining, the adjacent coronal sections were analyzed, their means calculated, and used for the Kruskal–Wallis analysis. Post-hoc group comparisons were accomplished utilizing the Mann–Whitney U test. Results are expressed as means ± SEM. In all comparisons, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

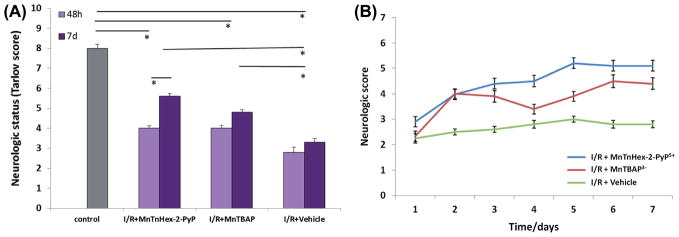

Neurologic status

The neurologic status was assessed daily through 48-h or 7-day post-reperfusion using composite neuroscore comprised from Tarlov score and inclined plane test. The assessments at 48 h and 7 day are given in Figure 3A, while daily assessments are shown in Figure 3B. All the animals in the control (sham) group were neurologically normal (grade 8). Motor scores in I/R groups at 48-h and 7-day post-reperfusion were significantly lower (P < 0.05) than those in the control group. The scores at 48-h post-reperfusion in the groups treated with I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ or I/R + MnTBAP3− were significantly higher versus group treated with vehicle. In I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ group, there is a significant difference between motor scores assessed at 48 h and 7 day. The motor scores in the I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ group were significantly higher (P < 0.05) compared with those in I/R + MnTBAP3− group and also in group treated with vehicle at 7 day post-reperfusion. Also, the motor scores in I/R + MnTBAP3− group were significantly higher (P < 0.05) compared with those in I/R + vehicle group. For most of 7 days, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ was more efficacious in suppressing motor neuron injury than MnTBAP3− (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Neurologic status of rats after I/R injury as affected by the treatment with MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and MnTBAP3−. (A) The neurologic status noted at 48 h (2D) and on 7 day (7D); (B) Neurologic score was taken daily. The status was assessed by Tarlov score and inclined plane test every day after ischemic insult, and is expressed as mean ± S.E.M. P < 0.05.

Analysis of fibrous astrocytes, GFAP, and NF-κB expression

Fibrous astrocytes in the white matter are characterized in the fluorescent microscope by GFAP (Figure 4A). The presence of GFAP in the gray matter of the ventral horn of the spinal cord indicates the glial scar formation, an inflammatory process. The absence of GFAP in the white matter of the spinal cord indicates the astrocytes death [107,108]. Rats which were treated with MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ or MnTBAP3− or received a vehicle showed a high number of GFAP-positive cells (P < 0.01) in comparison with the control group. The highest number of GFAP-positive cells in I/R + vehicle was statistically significant compared with MnTnHex-2-PyP5+-treated and MnTBAP3− -treated groups either at 48-h or 7-days post-reperfusion (P < 0.01). There was no statistical difference between the number of GFAP-positive cells in the groups treated with MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and MnTBAP3− (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Impact of MnPs on the expression of GFAP in fibrotic astrocytes at 48-h and 7-day post-I/R injury. (A) Immunofluorescence of GFAP. Immunofluorescence microscopy of paraffin sections of rat spinal cord stained with GFAP, a marker of astrocyte activation (reactive astrogliosis). The highest number of GFAP positive astrocytes was detected in the I/R + Vehicle group in comparison with the control group, or MnTnHex-2-PyP5+-treated or MnTBAP3−-treated group. The treatment with MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ or MnTBAP3− significantly decreased the number of GFAP-positive cells/mm2 either 48-h or 7-day post-reperfusion relative to I/R + Vehicle. (B) Quantification of GFAP-positive cells (fibrotic astrocytes) per mm2 in the gray matter of ventral horn of the spinal cord. Each value is mean ± S.E.M.*P < 0.01 I/R + vehicle vs control, and I/R + vehicle vs I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ or I/R + MnTBAP3−.

Once activated, NF-κB translocates from cytosol to nucleus to trigger the transcription of genes involved in cytokine production and cell survival. NF-κ B has also been implicated in processes of synaptic plasticity. We used immunofluorescence to detect the expression of NF-κB in the gray matter of ventral horn. Positive cells were those with nuclear accumulation of NF-κB (Figure 5A). The number of NF-κB-positive cells in the ventral horn of the spinal cord was significantly increased (P < 0.01) in all experimental groups versus control group. The NF-κB expression in the I/R + vehicle rats was significantly higher relative to I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ or I/R + MnTBAP3− group either at 48-h or 7-day post-reperfusion. NF-κB expression in I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ or I/R + MnTBAP3− group at 48-h post-reperfusion was similar to that in control group, and significantly lower relative to I/R + vehicle group (P < 0.01). At 7 days post-reperfusion, the NF-κB expression in I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and I/R + MnTBAP3− groups increased compared to 48-h post-reperfusion, but the difference was not significant (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Impact of MnPs on the expression of NF-κB at 48-h and 7-day post-I/R injury. (A) Immunofluorescence of NF-κB. Immunofluorescence microscopy of paraffin sections of rat spinal cord stained with NF-κB. I/R injury of the spinal cord causes NF-κB translocation to the nucleus. The highest number of nuclear NF-κB-positive astrocytes is in the I/R + Vehicle group. The treatment with MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ or MnTBAP3− decreases the number of nuclear NF-κB-positive cells, either 48-h or 7-day post-reperfusion. (B) Quantification of the impact of MnPs on NF-κB expression. The number of NF-κB-positive cells/mm2 in the ventral horns of spinal cord is significantly increased (*P < 0.01) in all experimental groups versus control group analyzed at 48 h. Both MnPs greatly inhibit upregulation of NF-κB relative to I/R + Vehicle. Each value is the mean ± S.E.M; *P < 0.01 I/R + vehicle vs control and I/R + vehicle vs I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ or I/R + MnTBAP3−.

Evaluation of oxidative stress

In order to verify the presence of spinal cord lipid and protein oxidative damage induced by I/R, the levels of lipid peroxidation products, TBARS, as well as the protein carbonyl formation were measured. Figure 6A shows spinal cord TBARS levels in control rats, rats treated with vehicle, and rats treated with either MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ or MnTBAP3−. An overall ANOVA revealed a statistically significant effect of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and MnTBAP3− on the TBARS levels. Duncan ’ s multiple range test indicated that spinal cord TBARS levels in I/R injured rats treated with MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ or MnTBAP3− were significantly higher in comparison with control group. Further, the TBARS levels in I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ or I/R + MnTBAP3− group were significantly decreased in comparison with those in I/R + vehicle group (Figure 6A). There were no differences demonstrated with respect to the time post-reperfusion.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of the impact of MnPs on the oxidative stress in rat spinal cord 48 h and 7 days after I/R injury. A) TBARS levels (nmol MDA/mg protein) represent means ± SEM; B) representative immunoblots of protein carbonyls as a measure of oxidized proteins; and C) Quantified protein carbonyls (% of the control). The following are presented: control group; rats with I/R injury treated with MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, MnTBAP3−, or vehicle. I/R + vehicle is significantly different from control and I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ or I/R + MnTBAP3− (*P < 0.01). There were no differences between 48-h and 7-day treatment groups.

Figure 6B shows the immunoblots of oxidized proteins in the spinal cord and Figure 6C shows the quantification of blots in the rats from all experimental groups. A statistically significant effect of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and MnTBAP3− treatment on the levels of oxidized proteins was demonstrated (P = 0.01). In the I/R + vehicle rats, the levels of oxidized protein were significantly increased to 146.0% ± 8.8% at 48-h and to 163% ± 7.4% at 7-day post-reperfusion relative to the control group (100%). The MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and MnTBAP3− treatment significantly reduced the I/R-induced increase in the level of oxidized proteins both at 48-h and 7-day post-reperfusion versus I/R + vehicle group (123.2% ± 8.3%, 132% ± 5.4%, 125.8% ± 5.9%, and 137.5% ± 4.7%).

Antioxidant enzyme activities

Figure 7A and B shows the activities of SOD and GPx enzymes in the rat spinal cords at 48-h and 7-day post-I/R. At 48-h post-reperfusion, the significantly increased GPx activity was found in I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ group compared to that in control, but not relative to I/R + vehicle group. GPx activity of the spinal cord decreased to a control level at 7 days post-reperfusion in all groups.

Figure 7.

Impact of MnPs on the activities of GPx (A) and SOD enzymes (B). A) GPx activity; *P < 0.05 significant difference control vs I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ at 48 h; *P < 0.05 significant difference between 48 h and 7 days of reperfusion in the same group; B) SOD activity; *P < 0.05 significant difference of I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ at 48-h post-I/R vs control and I/R + MnTBAP3− at 48-h and 7-day post-I/R vs control; *P < 0.05 significant difference between 48 h and 7 day time points in the same group of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+-treated rats and P < 0.05 significant difference between I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and I/R + MnTBAP3− groups at 7-day post-I/R injury. The bars represent mean values ± S.E.M.

A modest decrease in SOD activity in I/R + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ group, and less so in I/R + MnTBAP3− group, was demonstrated relative to a control group. The effect was more pronounced at 48 h than at 7 days (Figure 8). The data clearly demonstrate that neither MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ nor MnTBAP3− acted as SOD mimic.

Figure 8.

RNS-related chemistry of MnTBAP3− and ROS-based pathways of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ are presumably involved in suppression of NF-κB-controlled pro-inflammatory pathways and, in turn, I/R injury. MnPs were injected sc starting at 30 min before 45-min-ischemia and then every 12 h at 1.5 mg/kg for either 48-h or 7-day post-I/R. The suppression of astrogliosis, NF-κB expression, and oxidative stress (lipid peroxidation and protein carbonyl formation) was demonstrated by both MnPs. Further, motor neuron activity was significantly restored by both MnPs. While I/R itself increases GPx activity, no impact of MnPs on SOD and GPx activities was observed, suggesting that none of MnPs acted as SOD mimic in this model of oxidative stress.

Discussion

Suppression of I/R spinal cord injury by MnPs

Impact of MnPs on motor neuron function

Both MnPs improved motor neuron function as evaluated by Tarlov score and inclined plane test (Figure 2). When assessed on day-to-day basis, there is a trend suggesting that MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ is superior over MnTBAP3− (Figure 2B). Such observation may be explained by higher ability of more lipophilic MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ to cross blood–brain barrier [109]. As this is the only set of data from this study indicating the advantage of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ over MnTBAP3−, we have decided to stay away from strong conclusions. A combined dose-dependent/mechanistic study is in progress and aims to differentiate further between the therapeutic effects of these two MnPs.

Impact of MnPs on astrocyte fibrosis and NF-κB expression

The activation of astrocytes, known as reactive astrogliosis, is a hallmark of astrocytes’ response to all forms of CNS injuries [110]. Its molecular triggers in ischemia/reperfusion are still largely unknown, but seem to involve NF-κB, p38 MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase), and nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2) pathways [95,107,108,110,111]. The expression of GFAP has become a prototypical marker for immunohistochemical identification of fibrous astrocytes. The astrocytes are the most abundant glial cells of the spinal cord and are involved in the scarring process of the spinal cord following ischemic injury. The increase of GFAP expression is essential for the process of reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation [112]. Herein, we have found that astrocytes exhibited upregulation of GFAP post-I/R (Figure 4). The number of GFAP-positive cells was significantly reduced in injured spinal cord treated with either MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ or MnTBAP3− (Figure 4).

The trend in astrogliosis, affected by MnPs, is paralleled by NF-κB expression (Figures 4 and 5). The NF-κB proteins comprise a family of structurally related eukaryotic transcription factors that are involved in the control of a large number of physiological cellular processes, such as immune and inflammatory responses, developmental processes, cellular growth, and apoptosis [107]. NF-κB is present as a latent, inactive complex in the cytoplasm. When a cell receives extracellular signal, NF-κB rapidly enters the nucleus and activates gene expression. Upon ischemic injury, the excessive activation of NF-κB leads to a destructive inflammatory response, phenomenon referred to as I/R injury [96]. I/R caused large increase in the NF-κB-positive cells, which was greatly reduced by both MnPs almost to the level in control rats. The suppression of NF-κB with MnPs (Figure 5) reduced secondary injury, as demonstrated by reduced astrogliosis (Figure 4), lipid peroxidation, and protein oxidation (Figure 6), which in turn improved the motor neuron activity (Figure 3).

Impact of MnPs on oxidative stress

Reactive species were upregulated by I/R oxidative insult. The primary oxidative stress was further maintained/enhanced by the upregulation of NF-κB-driven pro-inflammatory pathways [97,98]. This resulted in oxidation of biomolecules as evidenced here with lipids and proteins. Both MnPs suppressed lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation to a similar extent (Figure 6). MnPs presumably scavenged reactive species formed during a short period of initial I/R injury. Yet, the impact of initial oxidative insult is further amplified over a long course of time by excessive upregulation of NF-κB [93,94]. We have clearly shown in our rat middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) I/R studies [93,94] that MnPs were protective when administered as a single injection given either very early at 5 min after reperfusion, or as late as 6 h after post-reperfusion. Such data show that the effect does not occur at the moment of reperfusion only (when most of the reactive species are produced), but at cellular transcription also. The effect of MnP, however, fades away eventually unless its administration continues over a longer period of time in order to suppress cycling secondary inflammatory processes. Several MnPs (MnTE-2-PyP5+, MnTDE-2-ImP5+, and MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ ) suppress NF-κB activation in stroke and subarachnoid hemorrhage [50,94]. Based on reported data and evidence provided herein, we may safely conclude that both MnPs suppress I/R spinal cord injury by impacting secondary oxidative stress, and that such effect is in great part controlled by NF-κB downregulation.

Impact of MnPs on endogenous antioxidative defenses

GPx activity: At 48-h post-reperfusion, due to ischemic injury, the GPx activity was increased in all groups relative to control non-injured, non-treated group of rats (Figure 7). At 7 days it was restored to control levels. SOD-like activity: The increased activity of SOD by MnPs has not been observed herein, which suggests that none of MnPs acted as SOD mimic (Figure 7). If any, the data indicate that SOD activity was somewhat reduced at 48 h. It is still possible that SOD enzyme had been upregulated, but was inactivated by reactive oxygen species (ROS)/reactive nitrogen species (RNS). The nitration of MnSOD enzyme with ONOO− has been reported [113,114]. MnTBAP3− is able to nitrate aromatic compounds with ONOO− [114,115]. The upregulation versus inactivation of SOD enzymes will be addressed in future studies.

Our data imply that pathways other than SOD-related pathways are implicated in the therapeutic actions of these two MnPs. The data agree with recent discussion of Liochev on (perhaps) irrelevance of the in vivo SOD-like actions of MnPs in their therapeutic potential [116]. These data further agree with a study on rat kidney I/R, where MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, being a part of a mixture of drugs, upregulated numerous endogenous antioxidative defenses (including SOD and GPx). The upregulation of SOD strongly implied that MnP had not acted as SOD mimic in that model (For further discussion, read the section “Reactivity toward signaling proteins”).

Are the therapeutic effects of vastly diffrent MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and MnTBAP3− controversal or simply not yet understood?

SOD-like activity

While on the first sight the issue may be viewed as controversial, it may, however, simply result from the insufficient knowledge of the chemistry and biology of MnPs. We have thus far gained knowledge on at least some of the pathways which may be operative. Yet, we are constantly reminded that (i) still we know little about the chemistry and biology of metal complexes and (ii) therefore other pathways may be operative. This is the first in vivo animal study providing a direct comparison of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and MnTBAP3− on their therapeutic efficacy in rat spinal cord I/R injury (Figure 1). The strong therapeutic effects obtained herein, under identical experimental conditions, have justified further dose-related and mechanistic studies.

MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ is an efficacious SOD mimic with rate constant for the catalysis of O2·− dismutation of log kcat(O2·−) = 7.34 (Table I) [7,8,10,12,14]. For the family of SOD enzymes, log kcat(O2·−) is reported to be in the range of 8.64–9.3 (Table I). Its high SOD-like activity is a result of the favorable thermodynamics (E1/2 = + 314 mV vs NHE) and kinetics, which are based on five positive charges in close proximity to the metal site. This allows for the superior catalysis of O2− dismutation (Eqs. 1 and 2). Additionally, its lipophilic character, based on four hydrophobic n-hexylpyridyl substituents, greatly contributes to its transport across membranes mostly across blood–brain barrier and mitochondrial membranes [109]. This in turn results in its high therapeutic efficacy. However, anionic compound, MnTBAP3−, lacks proper thermodynamics for O2·− dismutation; the relatively high electron richness of Mn site as indicated by its negative metal-centered reduction potential, E1/2 = −196 mV vs NHE precludes its reduction with O2·− in the 1st step of the dismutation process (Eq. 1, charges on periphery of MnP are omitted) [10,12,57], thus preventing a catalytic cycle.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Further, with four negatively charged carboxylates on its periphery, there is a repulsion of anionic O2·− from the anionic carboxylates of MnTBAP3−. Consequently, MnTBAP3− is not an SOD mimic. Thus, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ does, but MnTBAP3− does not, allow SOD-deficient organisms—prokaryotic E. coli and eukaryotic yeast S. cerevisiae—to grow aerobically as well as wild-type strains [51]. These assays are O2·−-specific and are routinely used to evaluate the SOD-like potency of MnPs and other types of SOD mimics. The reader is directed for further details to references [7,8,10,12,14,117].

Catalase-like activity

None of MnPs, including MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and MnTBAP3−, have any significant catalase-like activity ([37] Maia et al., SFRBM Meeting 2014, submitted) (Table I). The kcat (H2O2) is 5.84 and 28.3 M− 1s− 1, while it is 1.5 × 106 M−1 s−1 for the catalase enzyme itself, thus representing 0.0004 and 0.0018% of enzyme activity.

Reactivity toward cellular reductants

MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ cycles with cellular reductants, such as GSH and ascorbate, with Mn in + 3 and + 4 oxidation states (see details [12,133,136]). Yet, MnIIITBAP3− is very electron-rich (as indicated by its very negative E1/2) and, therefore, is very stable in its Mn + 3 oxidation state. It, therefore, does not favor reaction (reduction) with electron-donating species, such as ascorbate and glutathione. Only strong and not biologically relevant reductant, such as sodium dithionite—Na2S2O4, is able to reduce it to MnIITBAP4−. Alternatively, ligand binding to its Mn site may change its reduction potential, thus facilitating reduction of Mn site from + 3 to + 2 (see below).

Reactivity toward RNS

We have thus far also explored the chemistry and biology of MnPs with RNS, ·NO, HNO, and ONOO− [10,12,117,124]. MnTBAP3− reacts with ONOO− at more than 2 log units slower than MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, kred = 1.05 × 105 M− 1 s− 1 (Table I) [69]. The lower kred(ONOO−) is due to the reluctance of a fairly electron-rich Mn site to bind the anionic ONOO−. The additional unfavorable electrostatics, that is, the repulsion of anionic ONOO− from anionic MnTBAP3− is, however, absent in its reactions with ·NO and HNO. MnTBAP3− reacts with ·NO only after binding with an appropriate ligand modifies its reduction potential; the nitrosylated complex (NO)MnIITBAP4− was formed in the presence of ·NO and endogenous antioxidant, uric acid [137]. Quite recently, Doctorovich’s group has reported that MnTBAP3− rapidly reacts with HNO, a species which has recently gained increased interest due to its biological relevance [126] (Table I). The product is identical to the one formed in reaction with ·NO after urate binding: (NO) MnIITBAP4−. The reactivity of MnTBAP3− toward HNO is supported by thermodynamics. The pH-dependent reduction potential of the ·NO/HNO couple at pH 7 is E’ = + 550 mV vs NHE: ·NO + 1e− + H+ ---> HNO [138]. If oxidation of nitroxyl, given by HNO --> ·NO + 1e− + H+(E′ = + 550 mV vs NHE), couples with reduction of MnP, Mn(III)P+ + 1e− ---> Mn(II)P where E1/2 = −194 mV vs NHE, then ΔE = + 356 mV. This indicates a thermodynamically favored process. The spontaneity of the reaction would depend on pH; at a very low gastric pH, it would not be favored, but it would occur at neutral pH. Further, Filipovic et al. have recently demonstrated that HNO and a metal center of an Fe porphyrin can eventually S-nitrosate proteins via H2 S-assisted mechanism [102]. The same has been shown with Mn(II) cyclic polyamine-based SOD mimic [139]. This suggests that similar mechanism may be operative for MnTBAP3−-driven inhibition of NF-κB and in turn suppression of pro-inflammatory pathways.

Reactivity toward signaling proteins

The reactivity of MnTBAP3− toward RNS, and the impact on NF-κB, lead us to hypothesize that MnTBAP3− may be involved in the modification of NF-κB protein cysteine, followed by the inactivation of its transcriptional activity. Such scenario may explain the beneficial effects of MnTBAP3−. Our hypothesis is based on several recent studies where modification of cysteines of signaling proteins, with their subsequent inactivation, has been implicated in the modes of actions of two different classes of SOD mimics. The modification of cysteines was shown to occur via either ROS [99,100,140] or RNS [103]. It has recently been shown that Mn(II) cyclic polyamine-based SOD mimic could react with ·NO, whereby oxidizing and reducing it [101]. Such compound presumably oxidatively modifies cysteine of Keap1 via ·NO/HNO/H2S biology, whereby activating transcription factor Nrf2. Nrf2, in turn, controls levels of endogenous antioxidant defenses. The Nrf2 upregulation is a likely scenario in the pro-oxidant action of a natural compound, curcumin, commonly regarded as antioxidant [141]. Sheng et al. published extensively on a stroke I/R MCAO model, where MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and MnTDE-2-ImP5+ inhibit DNA binding of NF-κB due to the modification of the cysteines in their p50 and p65 subunits [50,94]. This agrees well with substantial evidence provided by Tome’s group that few Mn(III) N-substituted pyridylporphyrins, rather than acting as antioxidants, act indeed as pro-oxidants and oxidize cysteines of NF-κB whereby suppressing its transcriptional activities [100,140]. That is further in agreement with the data from Piganelli’s group which suggest that oxidation of cysteine of p50 subunit of NF-κB, upon nuclear translocation, suppresses immune response during beta islet cell transplant [11,142]. Our work on rat kidney I/R injury demonstrated that MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ (as a part of mixture containing growth factors and amino acids of Krebs cycle) upregulates a number of endogenous anti-oxidant enzymes — including mitochondrial and extracellular SOD, GPx, lactoperoxidase, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and thioredoxin reductase 1—and a set of peroxiredoxins—heat shock protein 70 (HSP-70) and phospho-heat shock factor 1 (pHSF-1) [42]. Importantly, this study clearly showed that MnP had not acted as an SOD mimic, but perhaps as a pro-oxidant inducing adaptive responses such as activating Nrf2 via oxidation of Keap1, in a manner similar to Mn(II) cyclic polyamine [102,103]. Such mode of action is further substantiated with data from Tome’s group indicating that MnTE-2-PyP5+ can S-glutathionylate other thiol-bearing proteins, such as complexes I, III, and IV of mitochondrial electron transport chain [99,100].

It is important to note that in all cases listed here, we do observe antioxidant effects; thus it is no wonder that researchers were frequently (and incorrectly) assigned them to antioxidative actions. We have already stressed that it is crucial to differentiate the effects we observe and actions that produce such effects [12,117].

Concluding remarks

We have summarized our discussion in Figure 8. It indicates the possible involvement of RNS-related chemistry in the therapeutic efficacy of MnTBAP3− and ROS-based effects of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, both of which exhibit suppression of NF-κB-controlled pro-inflammatory pathways in common. The mechanism of MnTBAP3− action on NF-κB was hypothesized to be related to RNS-based modification of cysteine which would inhibit its activation. Such conclusions are based on the (i) MnTBAP3−/RNS-related chemistry; (ii) Mn(III) N-substituted pyridylporphyrins-driven and N,N′-disubstituted imidazolylporphyrins-driven inactivation of NF-κB in a stroke I/R rat injury [50,93,94]; (iii) curcumin-driven suppression of astrogliosis/scar formation via NF-kB pathways [111]; (iv) inhibition of NF-kB DNA binding due to the S-glutathionylation of p65 subunit in a cancer study [100,143]; (v) islet cell transplant study [144], where two analogous MnPs suppressed immune responses via oxidation of p50 subunit followed by subsequent inhibition of NF-kB DNA binding [11,142]; (vi) oxidation of Keap1 (cysteine) of Nrf2 by cyclic polyamine-based SOD mimic [102,103]; (vii) parthenolide oxidation of Keap1 and activation of Nrf2 in a normal tissue with subsequent upregulation of endogenous antioxidant defenses [145], which is similar to the effect of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ in suppression of rat kidney I/R injury [42,45]; viii) role of Nrf2 in the inhibition of NF-kB and p38 MAPK phosphorylation in the hyper-activation of microglia cells/astrogliosis [95]; and (ix) role of NF-kB in astrogliosis and CNS injuries in general [95,107,108,110,111].

Taken together, data reported elsewhere and our data strongly suggest that NF-κB may be the common pathway for the involvement of two MnPs having entirely different chemistry and biology in suppression of I/R-driven inflammation. MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ has SOD-like properties, while MnTBAP3− is not an SOD mimic. Further, neither of the two acted in this model as SOD mimic. The chemistry and biology of MnPs is complex and difficult to comprehend even to the scientists with chemical background. It is thus of no surprise that biologists rely on the manuscripts, most of which are written by biologists also [116,146–148]; they would have to put in additional efforts in order to fully understand the coordination chemistry of metalloporphyrins that accounts for their therapeutic effects.

Understanding the mechanism of action of redox-active drugs may be irrelevant from clinical perspective as long as they are promising therapeutically [146]. Yet, their mechanism of action is critical for drug development, and especially when such drugs are used as tools to gain insight into the cellular metabolism and pathways involved in pathological disorders. Incorrect assignments of the pathways do not benefit drug development, understanding of the cellular redoxome, and identifying their interventions when perturbed. Increased understanding of their actions will result in increased understanding of cellular redox biology under physiological and pathological conditions. It is important to understand that what we observe may be the consequence of a complex set of interactions. Multiple approaches, both pharmacological and genetic, along with direct measurements of cellular and subcellular localization of SOD mimics are essential to safely identify the species or pathways involved [7,8,10,12,14,117]. Only such experimental strategies could eventually allow researchers to safely propose that mimicking either CuZnSOD or MnSOD accounts at least in part for the observed therapeutic effects of those compounds [149–151].

Highlights.

An SOD mimic, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, and non-SOD mimic, MnTBAP3−, exert anti-inflammatory effects on rat spinal cord I/R injury.

Neither MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ nor MnTBAP3− acted as SOD mimic in this model.

Downregulation of NF-κB pathways appears to be a common pathway for both MnPs, and results in suppression of lipid peroxidation, protein carbonyl formation, astrogliosis and NF-kB expression, and restoration of motor neuron function.

Acknowledgments

Ines Batinic-Haberle and Artak Tovmasyan acknowledge NIH-U19-AI-067798 and IBH general research funds. Tanja Celic, Josip Spanjol, Mirna Bobinac, and Dragica Bobinac acknowledge the grant 062-0620226-0207 from the Ministry of Science, Education and Sport of the Republic of Croatia. The input of Sara Goldstein on the reactivity of SOD enzymes toward species other than O2− is greatly appreciated.

Abbreviations

- I/R

ischemia/reperfusion

- IF

immunofluorescence

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- GPx

glutathione peroxidase

- HSP-70

heat shock protein 70

- MnTnHex-2-PyP5+

Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(N-n-hexylpyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin

- MnTBAP3−

Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(4-carboxylatophenyl)porphyrin

- MnP

Mn(III) porphyrin

- MnIIIP

MnP with Mn in + 3 oxidation state

- MnIIP

MnP with Mn in + 2 oxidation state

- MnTDE-2-ImP5+

Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(N,N′-diethylimidazolium-2-yl)porphyrin—AEOL10150

- MnTE-2-PyP5+

Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin—AEOL10113

- E1/2

metal-centered reduction potential for MnIIIP/MnIIP redox couple

- log kcat(O2·−)

rate constant for the catalysis of O2·− dismutation to O2 and H2O2 by MnP

- log kred(ONOO−)

rate constant for the reduction of peroxynitrite to ·NO2 with MnP

- log kcat(H2O2)

rate constant for the catalysis of H2O2 dismutation to O2 and H2O by MnP

- sc

subcutaneous

- ip

intraperitoneal

- iv

intravenous

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- Nrf2

nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- TBARS

thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances

- MCAO

middle cerebral artery occlusion

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no declarations of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Svensson LG, Crawford ES, Hess KR, Coselli JS, Safi HJ. Experience with 1509 patients undergoing thoracoabdominal aortic operations. J Vasc Surg. 1993;17:357–368. discussion 368–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wan IY, Angelini GD, Bryan AJ, Ryder I, Underwood MJ. Prevention of spinal cord ischaemia during descending thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;19:203–213. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(00)00646-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez-Arizala A, Green BA. Hypothermia in spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 1992;9:S497–S505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zvara DA, Colonna DM, Deal DD, Vernon JC, Gowda M, Lundell JC. Ischemic preconditioning reduces neurologic injury in a rat model of spinal cord ischemia. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:874–880. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00559-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taira Y, Marsala M. Effect of proximal arterial perfusion pressure on function, spinal cord blood flow, and histopathologic changes after increasing intervals of aortic occlusion in the rat. Stroke. 1996;27:1850–1858. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.10.1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temiz C, Solmaz I, Tehli O, Kaya S, Onguru O, Arslan E, Izci Y. The effects of splenectomy on lipid peroxidation and neuronal loss in experimental spinal cord ischemia/reperfusion injury. Turk Neurosurg. 2013;23:67–74. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.6825-12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batinic Haberle I, Tovmasyan A, Spasojevic I. The complex mechanistic aspects of redox-active compounds, commonly regarded as SOD mimics. BioInorg React Mech. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batinic-Haberle I, Rajic Z, Tovmasyan A, Reboucas JS, Ye X, Leong KW, et al. Diverse functions of cationic Mn(III) N-substituted pyridylporphyrins, recognized as SOD mimics. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1035–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Batinic-Haberle I, Reboucas JS, Benov L, Spasojevic I. Chemistry, biology and medical effects of water soluble metalloporphyrins. In: Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guillard R, editors. Handbook of Porphyrin Science. Vol. 11. Singapore: World Scientific; 2011. pp. 291–393. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batinic-Haberle I, Reboucas JS, Spasojevic I. Superoxide dismutase mimics: chemistry, pharmacology, and therapeutic potential. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:877–918. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batinic-Haberle I, Spasojevic I, Tse HM, Tovmasyan A, Rajic Z, St Clair DK, et al. Design of Mn porphyrins for treating oxidative stress injuries and their redox-based regulation of cellular transcriptional activities. Amino Acids. 2012;42:95–113. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0603-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batinic-Haberle I, Tovmasyan A, Roberts ER, Vujaskovic Z, Leong KW, Spasojevic I. SOD Therapeutics: Latest insights into their structure-activity relationships and impact on the cellular redox-based signaling pathways. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:2372–2415. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miriyala S, Spasojevic I, Tovmasyan A, Salvemini D, Vujaskovic Z, St Clair D, Batinic-Haberle I. Manganese superoxide dismutase, MnSOD and its mimics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:794–814. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tovmasyan A, Sheng H, Weitner T, Arulpragasam A, Lu M, Warner DS, et al. Design, mechanism of action, bioavailability and therapeutic effects of mn porphyrin-based redox modulators. Med Princ Pract. 2013;22:103–130. doi: 10.1159/000341715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aguilo JI, Iturralde M, Monleon I, Inarrea P, Pardo J, Martinez-Lorenzo MJ, et al. Cytotoxicity of quinone drugs on highly proliferative human leukemia T cells: reactive oxygen species generation and inactive shortened SOD1 isoform implications. Chem Biol Interact. 2012;198:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Kafaji G, Golbahar J. High glucose-induced oxidative stress increases the copy number of mitochondrial DNA in human mesangial cells. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:754946. doi: 10.1155/2013/754946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang M, Bany-Mohammed F, Kenney MC, Beharry KD. Effects of a superoxide dismutase mimetic on biomarkers of lung angiogenesis and alveolarization during hyperoxia with intermittent hypoxia. Am J Transl Res. 2013;5:594–607. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coriat R, Nicco C, Chereau C, Mir O, Alexandre J, Ropert S, et al. Sorafenib-induced hepatocellular carcinoma cell death depends on reactive oxygen species production in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:2284–2293. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crump KE, Langston PK, Rajkarnikar S, Grayson JM. Antioxidant treatment regulates the humoral immune response during acute viral infection. J Virol. 2013;87:2577–2586. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02714-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui YY, Qian JM, Yao AH, Ma ZY, Qian XF, Zha XM, et al. SOD mimetic improves the function, growth, and survival of small-size liver grafts after transplantation in rats. Transplantation. 2012;94:687–694. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182633478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dalgaard LT. UCP2 mRNA expression is dependent on glucose metabolism in pancreatic islets. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;417:495–500. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.11.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyde BB, Liesa M, Elorza AA, Qiu W, Haigh SE, Richey L, et al. The mitochondrial transporter ABC-me (ABCB10), a downstream target of GATA-1, is essential for erythropoiesis in vivo. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1117–1126. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue T, Suzuki-Karasaki Y. Mitochondrial superoxide mediates mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum dysfunctions in TRAIL-induced apoptosis in Jurkat cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;61C:273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jabaut J, Ather JL, Taracanova A, Poynter ME, Ckless K. Mitochondria-targeted drugs enhance Nlrp3 inflammasome-dependent IL-1beta secretion in association with alterations in cellular redox and energy status. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;60:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jamaluddin MS, Yan S, Lu J, Liang Z, Yao Q, Chen C. Resistin increases monolayer permeability of human coronary artery endothelial cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolamunne RT, Dias IH, Vernallis AB, Grant MM, Griffiths HR. Nrf2 activation supports cell survival during hypoxia and hypoxia/reoxygenation in cardiomyoblasts; the roles of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Redox Biol. 2013;1:418–426. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luanpitpong S, Chanvorachote P, Nimmannit U, Leonard SS, Stehlik C, Wang L, Rojanasakul Y. Mitochondrial superoxide mediates doxorubicin-induced keratinocyte apoptosis through oxidative modification of ERK and Bcl-2 ubiquitination. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1643–1654. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martino CF, Castello PR. Modulation of hydrogen peroxide production in cellular systems by low level magnetic fields. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pongjit K, Chanvorachote P. Caveolin-1 sensitizes cisplatin-induced lung cancer cell apoptosis via superoxide anion-dependent mechanism. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;358:365–373. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0988-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarre A, Gabrielli J, Vial G, Leverve XM, Assimacopoulos-Jeannet F. Reactive oxygen species are produced at low glucose and contribute to the activation of AMPK in insulin-secreting cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.10.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schrammel A, Mussbacher M, Winkler S, Haemmerle G, Stessel H, Wolkart G, et al. Cardiac oxidative stress in a mouse model of neutral lipid storage disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1831:1600–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tochigi M, Inoue T, Suzuki-Karasaki M, Ochiai T, Ra C, Suzuki-Karasaki Y. Hydrogen peroxide induces cell death in human TRAIL-resistant melanoma through intracellular superoxide generation. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:863–872. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yon JM, Baek IJ, Lee BJ, Yun YW, Nam SY. Emodin and [6]-gingerol lessen hypoxia-induced embryotoxicities in cultured mouse whole embryos via upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha and intracellular superoxide dismutases. Reprod Toxicol. 2011;31:513–518. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Day BJ, Shawen S, Liochev SI, Crapo JD. A metalloporphyrin superoxide dismutase mimetic protects against paraquat-induced endothelial cell injury, in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:1227–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee BI, Chan PH, Kim GW. Metalloporphyrin-based superoxide dismutase mimic attenuates the nuclear translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor and the subsequent DNA fragmentation after permanent focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Stroke. 2005;36:2712–2717. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000190001.97140.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muscoli C, Cuzzocrea S, Ndengele MM, Mollace V, Porreca F, Fabrizi F, et al. Therapeutic manipulation of peroxynitrite attenuates the development of opiate-induced antinociceptive tolerance in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3530–3539. doi: 10.1172/JCI32420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tovmasyan A, Weitner T, Jaramillo M, Wedmann R, Roberts E, Leong KW, et al. We have come a long way with Mn porphyrins: from superoxide dismutation to H2O2-driven pathways. Free Rad Biol Med. 2013;65:S133. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Batinic-Haberle I, Keir ST, Rajic Z, Tovmasyan A, Bigner DD. Lipophilic Mn porphyrins in the treatment of brain tumors. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:S119. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Batinic-Haberle I, Keir ST, Rajic Z, Tovmasyan A, Spasojevic I, Dewhirst MW, Bigner DD. Glioma growth suppression via modulation of cellular redox status by a lipophilic Mn porphyrin. Mid-Winter SPORE Meeting; 2011. pp. 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beausejour CM, Palacio L, Le O, Batinic-Haberle I, Sharpless NE, Marcoux S, Laverdiere C. Cell Senescence in Cancer and Ageing. Hinxton, Cambridge, UK: Wellcome Trust Genome Campus; 2013. Decreased neurogenesis following exposure to ionizing radiation: A role for p16INK4a-induced senescence. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cline JM, Dugan G, Bourland D, Perry DL, Stitzel JD, Weaver AA, et al. Post-irradiation treatment with MnTnHex-2-PyP5 + mitigates radiation pneumonitis and fibrosis in the lungs of non-human primates after whole-thorax exposure to ionizing radiation. Radiat Res. 2013 doi: 10.3390/antiox7030040. In Revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen J, Dorai T, Ding C, Batinic-Haberle I, Grasso M. The administration of renoprotective agents extends warm ischemia in a rat model. J Endourol. 2013;27:343–348. doi: 10.1089/end.2012.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crow JP. Catalytic antioxidants to treat amyotropic lateral sclerosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;15:1383–1393. doi: 10.1517/13543784.15.11.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dogan S, Unal M, Ozturk N, Yargicoglu P, Cort A, Spasojevic I, et al. Manganese porphyrin reduces retinal injury induced by ocular hypertension in rats. Exp Eye Res. 2011;93:387–396. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dorai T, Fishman AI, Ding C, Batinic-Haberle I, Goldfarb DS, Grasso M. Amelioration of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury with a novel protective cocktail. J Urol. 2011;186:2448–2454. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Drobyshevsky A, Luo K, Derrick M, Yu L, Du H, Prasad PV, et al. Motor deficits are triggered by reperfusion-reoxygenation injury as diagnosed by MRI and by a mechanism involving oxidants. J Neurosci. 2012;32:5500–5509. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5986-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gauter-Fleckenstein B, Fleckenstein K, Owzar K, Jiang C, Batinic-Haberle I, Vujaskovic Z. Comparison of two Mn porphyrin-based mimics of superoxide dismutase in pulmonary radioprotection. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:982–989. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.10.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pollard JM, Reboucas JS, Durazo A, Kos I, Fike F, Panni M, et al. Radioprotective effects of manganese-containing superoxide dismutase mimics on ataxia-telangiectasia cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:250–260. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saba H, Batinic-Haberle I, Munusamy S, Mitchell T, Lichti C, Megyesi J, MacMillan-Crow LA. Manganese porphyrin reduces renal injury and mitochondrial damage during ischemia/reperfusion. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1571–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sheng H, Spasojevic I, Tse HM, Jung JY, Hong J, Zhang Z, et al. Neuroprotective Efficacy from a Lipophilic Redox-Modulating Mn(III) N-Hexylpyridylporphyrin, MnTnHex-2-PyP: Rodent Models of Ischemic Stroke and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338:906–916. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.176701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tovmasyan A, Reboucas JS, Benov L. Simple biological systems for assessing the activity of superoxide dismutase mimics. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:2416–2436. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Batinic-Haberle I, Ndengele MM, Cuzzocrea S, Reboucas JS, Spasojevic I, Salvemini D. Lipophilicity is a critical parameter that dominates the efficacy of metalloporphyrins in blocking the development of morphine antinociceptive tolerance through peroxynitrite-mediated pathways. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fernandes AS, Florido A, Cipriano M, Batinic-Haberle I, Miranda J, Saraiva N, et al. Combined effect of the SOD mimic MnTnHex-2-PyP5 + and doxorubicin on the migration and invasiveness of breast cancer cells. Toxicol Lett. 2013;221S:S59–S256. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fernandes AS, Gaspar J, Cabral MF, Rueff J, Castro M, Batinic-Haberle I, et al. Protective role of ortho-substituted Mn(III) N-alkylpyridylporphyrins against the oxidative injury induced by tert-butylhydroperoxide. Free Radic Res. 2010;44:430–440. doi: 10.3109/10715760903555844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ashcraft KA, Palmer G, Spasojevic I, Batinic-Haberle I, Dewhirst MW. Radioprotection of the salivary gland and oral mucosa with a novel porphyrin-based antioxidant. 58th Annual Meeting of the Radiation Research Society; 2012. p. 129. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Melov S, Schneider JA, Day BJ, Hinerfeld D, Coskun P, Mirra SS, et al. A novel neurological phenotype in mice lacking mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase. Nat Genet. 1998;18:159–163. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reboucas JS, Spasojevic I, Batinic-Haberle I. Pure manganese(III) 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-benzoic acid)porphyrin (MnTBAP) is not a superoxide dismutase mimic in aqueous systems: a case of structure-activity relationship as a watchdog mechanism in experimental therapeutics and biology. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2008;13:289–302. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reboucas JS, Spasojevic I, Batinic-Haberle I. Quality of potent Mn porphyrin-based SOD mimics and peroxynitrite scavengers for pre-clinical mechanistic/therapeutic purposes. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2008;48:1046–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bagga P, Patel AB. Regional cerebral metabolism in mouse under chronic manganese exposure: implications for manganism. Neurochem Int. 2012;60:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hudnell HK. Effects from environmental Mn exposures: a review of the evidence from non-occupational exposure studies. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:379–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roth JA. Homeostatic and toxic mechanisms regulating manganese uptake, retention, and elimination. Biol Res. 2006;39:45–57. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602006000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ling X, Bao F, Qian H, Liu D. The temporal and spatial profiles of cell loss following experimental spinal cord injury: effect of antioxidant therapy on cell death and functional recovery. BMC Neurosci. 2013;14:146. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-14-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ling X, Liu D. Temporal and spatial profiles of cell loss after spinal cord injury: Reduction by a metalloporphyrin. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:2175–2185. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aladag MA, Turkoz Y, Sahna E, Parlakpinar H, Gul M. The attenuation of vasospasm by using a SOD mimetic after experimental subarachnoidal haemorrhage in rats. Acta Neurochirurgica. 2003;145:673–677. doi: 10.1007/s00701-003-0052-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Camara AK, Aldakkak M, Heisner JS, Rhodes SS, Riess ML, An J, et al. ROS scavenging before 27 degrees C ischemia protects hearts and reduces mitochondrial ROS, Ca2 + overload, and changes in redox state. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C2021–C2031. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00231.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Komeima K, Rogers BS, Lu L, Campochiaro PA. Antioxidants reduce cone cell death in a model of retinitis pigmentosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11300–11305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604056103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sheng H, Spasojevic I, Warner DS, Batinic-Haberle I. Mouse spinal cord compression injury is ameliorated by intrathecal cationic manganese(III) porphyrin catalytic antioxidant therapy. Neurosci Lett. 2004;366:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Genovese T, Mazzon E, Esposito E, Di Paola R, Murthy K, Neville L, et al. Effects of a metalloporphyrinic peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst, ww-85, in a mouse model of spinal cord injury. Free Radic Res. 2009;43:631–645. doi: 10.1080/10715760902954126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Batinic-Haberle I, Cuzzocrea S, Reboucas JS, Ferrer-Sueta G, Mazzon E, Di Paola R, et al. Pure MnTBAP selectively scavenges peroxynitrite over superoxide: comparison of pure and commercial MnTBAP samples to MnTE-2-PyP in two models of oxidative stress injury, an SOD-specific Escherichia coli model and carrageenan-induced pleurisy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bao F, DeWitt DS, Prough DS, Liu D. Peroxynitrite generated in the rat spinal cord induces oxidation and nitration of proteins: reduction by Mn (III) tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin. J Neurosci Res. 2003;71:220–227. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bao F, Liu D. Hydroxyl radicals generated in the rat spinal cord at the level produced by impact injury induce cell death by necrosis and apoptosis: protection by a metalloporphyrin. Neuroscience. 2004;126:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cuzzocrea S, Costantino G, Mazzon E, De Sarro A, Caputi AP. Beneficial effects of Mn(III)tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin (MnTBAP), a superoxide dismutase mimetic, in zymosan-induced shock. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:1241–1251. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hachmeister JE, Valluru L, Bao F, Liu D. Mn (III) tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin administered into the intrathecal space reduces oxidative damage and neuron death after spinal cord injury: a comparison with methylprednisolone. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:1766–1778. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leski ML, Bao F, Wu L, Qian H, Sun D, Liu D. Protein and DNA oxidation in spinal injury: neurofilaments–an oxidation target. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:613–624. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00500-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Levrand S, Vannay-Bouchiche C, Pesse B, Pacher P, Feihl F, Waeber B, Liaudet L. Peroxynitrite is a major trigger of cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:886–895. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu D, Bao F, Prough DS, Dewitt DS. Peroxynitrite generated at the level produced by spinal cord injury induces peroxidation of membrane phospholipids in normal rat cord: reduction by a metalloporphyrin. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:1123–1133. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu D, Ling X, Wen J, Liu J. The role of reactive nitrogen species in secondary spinal cord injury: formation of nitric oxide, peroxynitrite, and nitrated protein. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2144–2154. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu D, Shan Y, Valluru L, Bao F. Mn (III) tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin scavenges reactive species, reduces oxidative stress, and improves functional recovery after experimental spinal cord injury in rats: comparison with methylprednisolone. BMC Neurosci. 2013;14:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Loukili N, Rosenblatt-Velin N, Li J, Clerc S, Pacher P, Feihl F, et al. Peroxynitrite induces HMGB1 release by cardiac cells in vitro and HMGB1 upregulation in the infarcted myocardium in vivo. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;89:586–594. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Luo J, Li N, Paul Robinson J, Shi R. Detection of reactive oxygen species by flow cytometry after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;120:105–112. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]