Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of an abstinence-only intervention in preventing sexual involvement among young adolescents.

Design

Randomized controlled trial.

Setting

Urban public schools.

Patients/Participants

Participants were 662 African American grade 6 and 7 students.

Interventions

Eight-hour abstinence-only intervention targeted reduced sexual intercourse; 8-hour safer-sex-only intervention targeted increased condom use; 8-hour and 12-hour comprehensive interventions targeted sexual intercourse and condom use; 8-hour health-promotion control intervention targeted health issues unrelated to sexual behavior. Participants also were randomized to receive or not receive an intervention-maintenance program to extend intervention efficacy.

Main Outcome Measures

Primary outcome was self-report of ever having sexual intercourse by 24-month follow-up. Secondary outcomes were other sexual behaviors.

Results

Participants’ mean age was 12.2 years; 53.5% were girls; 84.4% were still enrolled at 24 months. Abstinence-only intervention reduced sexual initiation (risk ratio [RR] = 0.67, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48-0.96). The model-estimated probability of ever having sexual intercourse by 24-month follow-up was 33.5% in the abstinence-only intervention and 48.5% in the control group. Fewer abstinence-only intervention participants (20.6%) than control group participants (29.0%) reported having coitus in the previous 3 months during the follow-up period (RR = 0.94, 95% CI, 0.90-0.99). Abstinence-only intervention did not affect condom use. 8-hour (RR = 0.95, 95% CI, 0.92-0.996) and 12-hour comprehensive (RR = 0.95, 95% CI, 0.91-0.99) interventions reduced reports of having multiple partners compared with control group. No other differences between interventions and controls were significant.

Conclusions

Theory-based abstinence-only interventions may have an important role in preventing adolescent sexual involvement.

Keywords: sexual behavior, abstinence, intervention studies, HIV, sexually transmitted infection, adolescents, pregnancy, theory of planned behavior

Adolescents risk the deleterious consequences of early sexual involvement, including HIV,1 other sexually transmitted infections (STIs),2 and unintended pregnancies.3,4 In the US, these risks are especially great among African American adolescents.2,5,6 In 2005, 17% of the adolescents in the US were African Americans, but 69% of adolescents with HIV/AIDS were African Americans.5 Rates of STIs are highest among African Americans and adolescents, particularly adolescent girls.2 Pregnancy rates have been higher among African American adolescents than among their Latino and White counterparts.7 Adolescents who initiate sexual intercourse at younger ages have a greater risk of STI8 and pregnancy9 and report more sexual risk behaviors, including multiple sexual partners.10-11

Although considerable research suggests that behavioral interventions can reduce sexual behaviors tied to risk of STI among adolescents,12-14 including younger adolescents 11 to 15 years of age,15-18 a public policy debate has revolved around the appropriateness and efficacy of different sexual-risk-reduction interventions. Some have advocated abstinence interventions; others have advocated comprehensive interventions—abstinence and, for sexually active adolescents, condom use. Abstinence interventions have been criticized for containing inaccurate information, portraying sex in a negative light, employing a moralistic tone,19-20 and risking unintended adverse consequences.20-22 This debate notwithstanding, the US has primarily funded and promoted abstinence education both in the US and abroad,20 and many states have mandated that HIV/STI education for children stress abstinence.23-24

Despite the widespread implementation of abstinence interventions and the controversy regarding their appropriateness, few randomized controlled trials have tested their efficacy,12-14,22 which has led to calls for more rigorous abstinence intervention research.12,20,22,25 The ideal abstinence intervention would incorporate principles of efficacious HIV/STI risk-reduction behavioral interventions. It would draw upon formative research with the population and behavior change theory to address motivation and build skills to practice abstinence; it would not be moralistic; and it would not stress the “inadequacies” of condoms.

Here we report results of a trial on the efficacy of such a theory-based abstinence-only intervention. African American grade 6 and 7 students were randomly assigned to an 8-hour abstinence-only intervention, an 8-hour safer-sex-only intervention, an 8-hour or a 12-hour combined abstinence and safer-sex intervention, or an 8-hour health-promotion control group. We hypothesized that fewer participants in the abstinence-only intervention than in the control group would report ever having sexual intercourse by 24-month follow-up.

A common shortcoming of behavior-change interventions is that efficacy is demonstrated in the short term, but disappears at longer-term follow-up. This may be particularly a problem for abstinence interventions.15 Unlike many risk behaviors (e.g., cigarette smoking, drug use), sexual intercourse is an age-graded behavior; the expectation is that people will eventually have sexual intercourse. We designed a multifaceted intervention-maintenance program tailored to each intervention to extend the efficacy of the interventions. A secondary hypothesis, then, was that the intervention-maintenance program would enhance intervention efficacy.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 662 African American grade 6 and 7 students recruited from 4 public middle schools serving low-income African American communities in a city in the northeastern US recruited between September 2001 and March 2002 via announcements by project staff in assemblies, classrooms, and lunchrooms and letters to parents or guardians for the “Promoting Health among Teens (PHAT) Project” designed to reduce the chances that adolescents develop devastating health problems, including cardiovascular diseases, cancers, and STIs, including HIV.

Procedures

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania and the Research Ethics Board of the University of Waterloo approved the study. African American grade 6 and 7 students at the 4 participating schools who had written parent or guardian consent were eligible to participate. In this randomized controlled trial, students were stratified by age and gender and, using a computer-generated random number sequence, randomly allocated to an 8-hour abstinence-only intervention, an 8-hour safer-sex-only intervention, an 8-hour comprehensive intervention, a 12-hour comprehensive intervention, or an 8-hour health-promotion control intervention. They were also randomly assigned to intervention maintenance or no intervention maintenance and to a group of 6 to 8 participants. One researcher conducted the computer-generated random assignments and distributed the information to other researchers who executed the assignments.

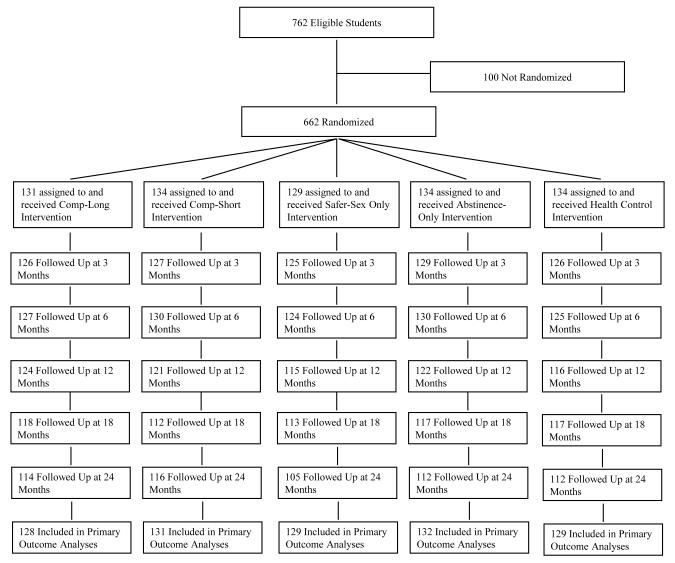

Adolescents were enrolled in the study in 4 cycles or replications, 1 at each of 4 schools. Figure 1 shows the number of adolescents randomized to each condition. The intervention and data collection sessions were implemented on Saturdays in classrooms at the participating schools.

Figure 1.

Progress of participating grade 6 and 7 African American students through the trial. Students who were not followed up were absent at the time of the follow-up session and failed to attend the make-up sessions for unknown reasons.

Experimental Conditions

The interventions were based on social cognitive theory,26-27 the theory of reasoned action,28-29 and its extension, the theory of planned behavior.30 They were highly structured, and facilitators implemented them following intervention manuals. Each intervention involved a series of brief group discussions, videos, games, brainstorming, experiential exercises, and skill-building activities. Four of the interventions consisted of 8 1-hour modules implemented over 2 sessions; one consisted of 12 1-hour modules implemented over 3 sessions. All 5 were pilot tested.

Abstinence-only intervention

The 8-hour abstinence-only intervention encouraged abstinence to eliminate the risk of pregnancy and STIs, including HIV. It was designed to: (a) increase HIV/STI knowledge, (b) strengthen behavioral beliefs supporting abstinence, including the belief that abstinence can prevent pregnancy, STIs, and HIV and the belief that abstinence can foster attainment of future goals, and (c) increase skills to negotiate abstinence and resist pressure to have sex. It was not designed to meet federal criteria for abstinence-only programs. For instance, the target behavior was abstaining from vaginal, anal, and oral intercourse until a time later in life when the adolescent is more prepared to handle the consequences of sex. The intervention did not contain inaccurate information, portray sex in a negative light, or employ a moralistic tone. The training and curriculum manual explicitly instructed the facilitators not to disparage the efficacy of condoms or allow the view that condoms are ineffective to go uncorrected.

Safer-sex-only intervention

The 8-hour safer-sex-only intervention encouraged condom use to reduce the risk of pregnancy and STIs, including HIV, if adolescents had sex. It was designed to: (a) increase HIV/STI knowledge, (b) enhance behavioral beliefs supporting condom use, and (c) increase skills to use condoms and negotiate condom use. It was not designed to influence abstinence.

Comprehensive interventions

Two comprehensive interventions combined the abstinence and safer-sex HIV risk-reduction interventions. One was a 12-hour intervention; one was an 8-hour intervention that contained similar content. Both targeted beliefs and skills to encourage abstinence and condom use. Both were designed to: (a) increase HIV/STI knowledge; (b) strengthen behavioral beliefs supporting abstinence; (c) strengthen behavioral beliefs supporting condom use; (d) increase skills to negotiate abstinence; and (e) increase skills to use condoms and negotiate condom use.

The 12-hour version contained the safer-sex content (4 hours), the abstinence content (4 hours), and the general content common to both single-component interventions (4 hours). If the 12-hour version had a larger effect than did the single component interventions, it would not have been possible to disentangle the beneficial effects of greater intervention length from the benefits of combining the two components. To control for this, the 8-hour version was the same length as the single-component interventions.

Health-promotion control intervention

The 8-hour health-promotion intervention, which served as the control, focused on behaviors associated with risk of heart disease, hypertension, stroke, diabetes, and certain cancers. It was designed to increase knowledge and motivation regarding healthful dietary practices, aerobic exercise, and breast and testicular self-examination and to discourage cigarette smoking. It controls for “Hawthorne effects” to reduce the likelihood that effects of the HIV interventions could be attributed to nonspecific features, including group interaction and special attention.31

Intervention-maintenance program

Participants were also randomly assigned to receive or not receive an intervention-maintenance program tailored to their intervention. It consisted of 2 3-hour “booster” intervention sessions (6 weeks and 3 months after initial intervention sessions), 6 issues of a newsletter, and 6 20-minute one-on-one counseling sessions over a 21-month period with their original facilitator.

Facilitators and Facilitator Training

The facilitators were 16 men and 51 women (mean age = 43.1 years); 61.2% had a Master’s Degree and 38.8% had a Bachelor’s Degree. All were African Americans except one Puerto Rican. We hired facilitators with the skills to implement any of the interventions, stratified them on gender and age, and randomly assigned them to receive 2.5 days of training to implement 1 of the 5 interventions. In this way, we randomized facilitators’ characteristics across interventions; hence, reducing the plausibility of attributing intervention effects to the facilitators’ pre-existing characteristics.

Outcomes

Participants completed pre-intervention, immediate post-intervention, and 3-, 6-, 12-, 18-, and 24-month follow-up questionnaires. Follow-up data were collected between January 2002 and August 2004. All questions had been pilot tested to ensure that they were clear and that the phrasing was appropriate for the population. Pre-intervention and follow-up questionnaires assessed sexual behavior, demographic variables, and mediator variables. The post-intervention questionnaire assessed mediator variables and evaluative ratings of the interventions.

The primary outcome for the abstinence-only intervention was report by the 24-month follow-up of ever having sexual intercourse. Secondary outcomes were other self-reported sexual behaviors in the previous 3 months: sexual intercourse; multiple partners (having sexual intercourse with 2 or more partners); unprotected intercourse (one or more sexual intercourse acts without using a condom); and consistent condom use (condom use during every sexual intercourse act).

Data collectors received 8 hours of training and were blind to the participants’ intervention condition. We took several steps to increase the validity of self-reported sexual behavior. To facilitate participants’ recall, we asked them to report their behaviors over a brief period (i.e., past 3 months),32 wrote the dates comprising the period on a chalkboard, and gave them calendars highlighting the period. To reduce the likelihood that participants would minimize or exaggerate, we stressed the importance of responding honestly, informing them that their responses would be used to create programs for other African American adolescents like themselves and that we could do so only if they answered the questions honestly. We assured the participants that their responses would be kept confidential and that code numbers rather than names would be used on the questionnaires. Participants signed an “agreement” pledging to answer the questions honestly, a procedure that has been shown to yield more valid self-reports on sensitive issues.33

Social Desirability Response Measure

The Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale34 included in the pre-intervention questionnaire assessed the tendency of participants to describe themselves in favorable, socially desirable terms.

Sample Size and Statistical Analyses

With alpha = .05, two-tailed, and 37.4% of the control group initiating sexual intercourse by 24-month follow-up, a total sample size of 563 participants completing the trial was projected to provide power of 80% to detect a difference of 16.8% in self-reported sexual intercourse between an HIV intervention condition and the control condition. We performed chi-square and t tests to analyze attrition.

To test intervention effects, we used an intention-to-treat approach in which participants’ data were analyzed regardless of the number of intervention or data collection sessions they attended. The efficacy of the HIV interventions on report by the 24-month follow-up of ever having sexual intercourse was tested using generalized linear regression with a log link, and the exponentiated coefficients, risk ratios (RR), and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported.35 We used either of two error distributions (either Bernoulli or Poisson with robust variance estimator) depending on whether predicted probabilities violated the 0,1 range of a probability. Effects of the HIV/STI interventions on recent sexual intercourse, multiple partners, unprotected intercourse, and consistent condom use over the 24-month follow-up period were tested using Poisson generalized estimating equations (GEE) with a log link.35 An unstructured working correlation matrix was specified in the GEE analyses.

Analyses on recent sexual intercourse, multiple partners, and unprotected intercourse controlled for the baseline measure of the criterion, time, intervention-maintenance condition, gender, and age. Analyses on ever had sexual intercourse excluded participants who reported ever having sexual intercourse at baseline and controlled for intervention-maintenance condition, gender, and age. Analyses on consistent condom use excluded participants who did not report sexual intercourse in the past 3 months and controlled for time, intervention-maintenance condition, gender, and age. The latter did not control for baseline measure because the small number of participants reporting recent sexual intercourse at both baseline and follow-up would have severely limited the sample size. The significance criterion was set at alpha = 0.05 except for post-hoc analyses comparing the abstinence-only and 8-hour comprehensive interventions where a Type-1-error-adjusted alpha of 0.05/2 = 0.025 was employed.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Sample

Table 1 summarizes selected participant characteristics at baseline. About 53.5% of participants were girls; 46.5% were boys. Age ranged from 10 to 15 years, with a mean of 12.2 (SD = 0.81); 44.7% were in grade 6 and 55.3% were in grade 7. About 33.7% lived with both of their parents. About 23.4% reported having experienced coitus at least once, 12.0% reported having coitus in the previous 3 months, 6.4% reported having multiple partners in the previous 3 months, and 2.9% reported having unprotected intercourse in the previous 3 months. Of those who reported intercourse in the previous 3 months, 67.1% reported consistent condom use. Only 2 respondents (0.3%) reported sexual relations with someone of their own gender.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Self-reported Sexual Behaviors of Participating African American Grade 6 and 7 Students, by Intervention Condition at Baseline.

| Intervention Condition |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Participants | 12-hour comprehensive |

8-hour comprehensive |

Safer Sex Only | Abstinence Only |

Health Control | |

| No. | 662 | 131 | 134 | 129 | 134 | 134 |

| No. (%) Female | 354/662 (53.5%) | 69/131 (52.7%) | 72/134 (53.7%) | 70/129 (54.3%) | 70/134 (52.2%) | 73/134 (54.5%) |

| No. (%) Grade 7 | 366/662 (55.3%) | 68/131 (51.9%) | 71/134 (53.0%) | 73/129 (56.6%) | 77/134 (57.5%) | 77/134 (57.5%) |

| No. (%) Live with both parents | 221/655 (33.7%) | 46/130 (35.4%) | 46/133 (34.6%) | 40/126 (31.8%) | 43/133 (32.3%) | 46/133 (34.6%) |

| No. (%) Ever had sexual intercourse | 153/655 (23.4%) | 31/128 (24.2%) | 28/133 (21.0%) | 32/127 (25.2%) | 27/133 (20.3%) | 35/134 (26.1%) |

| No. (%) Sexual intercourse in past 3 months | 79/657 (12.0%) | 14/130 (10.8%) | 14/132 (10.6%) | 15/128 (11.7%) | 16/133 (12.0%) | 20/134 (14.9%) |

| No. (%) Multiple sexual partners in past 3 months | 42/655 (6.4%) | 11/130 (8.5%) | 10/132 (7.6%) | 6/127 (4.7%) | 4/133 (3.0%) | 11/133 (8.3%) |

| No. (%) Unprotected intercourse in past 3 months | 19/655 (2.9%) | 3/130 (2.3%) | 2/131 (1.5%) | 7/127 (5.5%) | 1/133 (0.8%) | 6/134 (4.5%) |

| No. (%) Consistent condom use in past 3 months | 51/76 (67.1%) | 10/14 (71.4%) | 10/14 (71.4%) | 4/14 (28.6%) | 13/14 (92.9%) | 14/20 (70.0%) |

| No. (%) Randomized to Intervention Maintenance | 315/662 (47.6%) | 69/131 (52.7%) | 70/134 (52.2%) | 68/129 (52.7%) | 70/134 (52.2%) | 70/134 (52.2%) |

| Mean Age in years (Standard deviation) | 12.0 (0.8) | 11.9 (0.80) | 11.9 (0.8) | 12.0 (0.8) | 12.0 (0.8) | 12.0 (0.8) |

Intervention Attendance and Follow-up Retention

Figure 1 shows the flow of the participants through the trial. Of the 762 eligible students, 662 (86.9%) participated. We do not have information on the characteristics of the eligible students who did not participate. Attendance at intervention and data-collection sessions was excellent. All participants attended intervention session 1, and 642 or 97.0% attended session 2. Attendance at session 2 ranged from 95.5% to 98.5%, with no significant difference among interventions. Only the 12-hour comprehensive intervention had a session 3 and all participants attended it. Of the trial participants, 649 (98.0%) attended at least one of the follow-ups: 633 (95.6%) attended the 3-month, 636 (96.1%) attended the 6-month, 598 (90.3%) attended the 12-month, 577 (87.2%) attended the 18-month, and 559 (84.4%) attended the 24-month. The interventions did not differ significantly in retention at follow-up. Attending a follow-up session was unrelated to gender, age, living with both parents, and sexual behavior outcomes.

Effects on the Primary Outcome

Table 2 presents sexual behavior outcomes by intervention condition and time. Table 3 presents risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals for intervention efficacy on sexual behavior outcomes. The abstinence-only intervention reduced sexual initiation (P = 0.027). The model-estimated probability of ever having sexual intercourse by 24-month follow-up was 33.5% in the abstinence-only intervention and 48.5% in the health-promotion control group. The safer-sex and comprehensive interventions did not differ from the control group in sexual initiation.

Table 2.

Self-reported Sexual Risk Behavior by Intervention Condition and Time.

| Time |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Condition | Baseline | 3-Month | 6-Month | 12-Month | 18-Month | 24-Month |

| No. (%) Ever had sexual intercourse | ||||||

| 12-hour comprehensive | 0/97 (0.0) | 4/96 (4.2) | 11/98 (11.2) | 20/96 (20.8) | 32/93 (34.4) | 39/92 (42.4) |

| 8-hour comprehensive | 0/105 (0.0) | 9/99 (9.1) | 14/104 (13.5) | 23/96 (24.0) | 29/91 (31.9) | 40/97 (41.2) |

| Safer sex only | 0/95 (0.0) | 15/93 (16.1) | 22/92 (23.9) | 32/88 (36.4) | 39/87 (44.8) | 44/85 (51.8) |

| Abstinence only | 0/106 (0.0) | 5/102 (4.9) | 9/104 (8.7) | 20/98 (20.4) | 24/96 (25.0) | 31/95 (32.6) |

| Health control | 0/109 (0.0) | 8/94 (8.5) | 15/94 (16.0) | 20/89 (22.5) | 31/90 (34.4) | 41/88 (46.6) |

| No. (%) had sexual intercourse in past 3 months |

||||||

| 12-hour comprehensive | 14/130 (10.8) | 12/125 (9.6) | 18/127 (14.2) | 24/124 (19.4) | 32/118 (27.1) | 35/114 (30.7) |

| 8-hour comprehensive | 14/132 (10.6) | 19/126 (15.1) | 19/130 (14.6) | 33/121 (27.3) | 32/112 (28.6) | 38/116 (32.8) |

| Safer sex only | 15/128 (11.7) | 22/124 (17.7) | 21/122 (17.2) | 34/115 (29.6) | 40/113 (35.4) | 42/105 (40.0) |

| Abstinence only | 16/133 (12.0) | 15/129 (11.6) | 13/130 (10.0) | 27/121 (22.3) | 39/117 (33.3) | 33/112 (29.5) |

| Health control | 20/134 (14.9) | 26/126 (20.6) | 27/125 (21.6) | 25/116 (21.6) | 35/117 (29.9) | 42/112 (37.5) |

| No. (%) had multiple sexual partners in past 3 months |

||||||

| 12-hour comprehensive | 11/130 (8.5) | 7/126 (5.6) | 7/127 (5.5) | 13/124 (10.5) | 10/118 (8.5) | 16/114 (14.0) |

| 8-hour comprehensive | 10/132 (7.6) | 6/126 (4.8) | 6/129 (4.6) | 9/121 (7.4) | 16/112 (14.3) | 13/116 (11.2) |

| Safer sex only | 6/127 (4.7) | 13/125 (10.4) | 9/123 (7.3) | 15/114 (13.2) | 18/112 (16.1) | 19/102 (18.6) |

| Abstinence only | 4/133 (3.0) | 5/129 (3.9) | 5/130 (3.8) | 12/122 (9.8) | 21/115 (18.3) | 15/112 (13.4) |

| Health control | 11/133 (8.3) | 14/126 (11.1) | 19/125 (15.2) | 11/115 (9.6) | 18/117 (15.4) | 18/112 (16.1) |

| No. (%) had unprotected sexual intercourse in past 3 months |

||||||

| 12-hour comprehensive | 3/130 (2.3) | 5/126 (4.0) | 2/126 (1.6) | 7/124 (5.7) | 6/118 (5.1) | 8/113 (7.1) |

| 8-hour comprehensive | 2/131 (1.5) | 2/126 (1.6) | 1/130 (0.8) | 6/121 (5.0) | 10/111 (9.0) | 8/115 (7.0) |

| Safer sex only | 7/127 (5.5) | 5/125 (4.0) | 3/124 (2.4) | 7/111 (6.3) | 3/110 (2.7) | 9/103 (8.7) |

| Abstinence only | 1/133 (0.8) | 1/128 (0.8) | 1/129 (0.8) | 7/122 (5.7) | 8/117 (6.8) | 8/112 (7.1) |

| Health control | 6/134 (4.5) | 4/126 (3.2) | 11/125 (8.8) | 7/116 (6.0) | 7/117 (6.0) | 8/110 (7.3) |

| No. (%) used condoms consistently during intercourse in past 3 months |

||||||

| 12-hour comprehensive | 10/14 (71.4) | 8/13 (61.5) | 14/17 (82.4) | 16/23 (69.6) | 23/30 (76.7) | 26/35 (74.3) |

| 8-hour comprehensive | 10/14 (71.4) | 15/18 (83.3) | 17/18 (94.4) | 25/31 (80.6) | 21/32 (65.6) | 29/37 (78.4) |

| Safer sex only | 4/14 (28.6) | 16/21 (76.2) | 17/20 (85.0) | 24/34 (70.6) | 34/40 (85.0) | 31/42 (73.8) |

| Abstinence only | 13/14 (92.9) | 12/15 (80.0) | 11/13 (84.6) | 19/26 (73.1) | 31/39 (79.5) | 25/33 (75.8) |

| Health control | 14/20 (70.0) | 20/25 (80.0) | 15/26 (57.7) | 17/24 (70.8) | 27/34 (79.4) | 32/41 (78.0) |

Note. Ever had sexual intercourse excludes participants who reported sexual intercourse at baseline. Consistent condom use excludes participants who did not have sexual intercourse in the past 3 months.

Table 3.

Estimates of Intervention Effect Size (Risk Ratios) and 95% Confidence Intervals for Self-Reported Sexual Behavior Outcomes.

| Intervention Condition |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 12-hour comprehensive |

8-hour comprehensive |

Safer Sex Only | Abstinence Only | |

| Ever had sexual intercourse | 457 | 0.87 (0.64, 1.19) | 0.86 (0.63, 1.17) | 0.95 (0.72, 1.27) | 0.67 (0.48, 0.96) |

| Sexual intercourse in past 3 months | 657 | 0.95 (0.90, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | 0.94 (0.90, 0.99) |

| Multiple sexual partners in past 3 months | 655 | 0.95 (0.91, 0.99) | 0.96 (0.92, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.04) | 0.97 (0.93, 1.01) |

| Unprotected sexual intercourse in past 3 months | 655 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.02) | 0.97 (0.94, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) |

| Consistent condom use in past 3 months | 292 | 0.98 (0.82, 1.18) | 1.08 (0.92, 1.27) | 1.09 (0.94, 1.27) | 1.03 (0.88, 1.21) |

Note: The effect size estimate is the risk ratio (intervention coded “1” versus health control coded “0”) for each HIV/STI intervention condition. The risk ratios on ever had sexual intercourse was adjusted for intervention-maintenance condition, gender, and age at the 24-month follow-up. The risk ratios on consistent condom use were adjusted for time, intervention-maintenance condition, gender, and age over the entire follow-up period. All other risk ratios were adjusted for baseline measure of the criterion, time, intervention-maintenance condition, gender, and age over the entire follow-up period. N is the number of participants included in the analysis.

Effects on Other Sexual Behaviors

The abstinence intervention also significantly reduced recent sexual intercourse. The model-estimated probability of reporting intercourse in the past 3 months averaged over the 3-, 6-, 12-, 18-, and 24-month follow-ups was 20.6% in the abstinence-only intervention as compared with 29.0% in the control group (P = 0.019). The model-estimated probability was 20.6% in the 12-hour comprehensive intervention, a marginally significant difference (P = 0.057) from the control group. The safer-sex and 8-hour comprehensive interventions did not have significant effects on recent intercourse, as compared with the control group.

Abstinence-only intervention participants did not differ from the control group in reports of multiple partners (P = 0.133). Participants in the 8-hour group (P = 0.030; model-estimated probability, 8.8%) and 12-hour comprehensive interventions group (P = 0.020; model-estimated probability, 8.7%) were significantly less likely to report having multiple partners than were those in the control group (model-estimated probability, 14.1%). No other differences were statistically significant. None of the interventions had significant effects on consistent condom use or unprotected intercourse. In the sub-group of participants who had their sexual debut during the trial, there was no difference between the abstinence-only intervention and the control group in consistent condom use.

Post-hoc analyses revealed no significant differences between the abstinence intervention and the 8-hour comprehensive intervention on any sexual behavior outcome.

Social Desirability Bias

Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale scores were unrelated to self-reported sexual behavior, including abstinence, at baseline and did not interact with intervention condition to influence sexual behavior during the follow-up period.

Intervention Maintenance

Tests of Intervention Maintenance x Intervention Condition interactions revealed no evidence that the intervention-maintenance program moderated the efficacy of the interventions in reducing sexual initiation, recent sexual intercourse, or unprotected sexual intercourse. However, the Intervention Maintenance x Abstinence-only Intervention (P = 0.030) and Intervention Maintenance x 12-hour Comprehensive Intervention (P = 0.042) interactions on multiple partners were statistically significant. The abstinence-only intervention was more efficacious in reducing multiple partners than was the control group among those who received intervention-maintenance (RR = 0.93, 95% CI, 0.88-0.98, P = 0.006) as compared with those who did not (RR = 1.02, 95% CI, 0.96-1.08, P = 0.572). The 12-hour comprehensive intervention was more efficacious in reducing multiple partners than was the control group among those who received intervention-maintenance (RR = 0.91, 95% CI, 0.86-0.96, P = 0.004) as compared with those who did not (RR = 0.99, 95% CI, 0.93-1.06, P = 0.830).

No adverse events occurred during the study.

COMMENT

The present results indicate that a theory-based abstinence-only intervention reduced self-reported sexual involvement among African American grade 6 and 7 students, a population at high risk of pregnancy and STIs, including HIV. The abstinence-only intervention as compared with the health-promotion control intervention reduced by about 33% the percentage of students who ever reported having sexual intercourse by the time of the 24-month follow-up, controlling for grade, age, and intervention-maintenance condition. Although other studies have reported intervention-induced reductions in sexual intercourse among adolescents, this is the first randomized controlled trial to demonstrate that an abstinence-only intervention reduced the percentage of adolescents who reported any sexual intercourse over a long period following the intervention, in this case 24 months post-intervention.

We also found significant effects of the 8-hour and 12-hour comprehensive interventions on an important HIV/STD risk-related behavior. Both comprehensive interventions significantly reduced the incidence of multiple sexual partners as compared with the health control group. In addition, the 12-hour comprehensive intervention marginally significantly (P = 0.057) reduced the incidence of recent sexual intercourse as compared with the health control group.

A common shortcoming of health-behavior interventions is that behavior change is often short-lived, disappearing upon longer-term follow-up. We employed a multifaceted, tailored intervention-maintenance program to address this shortcoming. Although many trials have employed booster intervention sessions, this is one of few trials to test the efficacy of a randomly allocated strategy to extend interventions’ efficacy. We found only modest effects of the intervention-maintenance program in enhancing efficacy. It enhanced the efficacy of the abstinence-only and comprehensive interventions in reducing multiple partners compared with the control group, but did not enhance efficacy on sexual initiation, recent intercourse, or unprotected intercourse. Therefore, although the effects of our intervention maintenance component are promising, we encourage additional research to identify ways to extend the efficacy of HIV/STD risk reduction interventions.

A common concern about abstinence-only interventions is that they have the unintended effect of reducing condom use, that children exposed to such interventions are subsequently less likely to use condoms if they have sexual intercourse.20-21,36 Contrary to this, however, a randomized controlled trial37 and a literature review38 found no effects of abstinence interventions on condom use. Similarly, in this trial the abstinence-only-intervention participants did not differ in self-reported consistent condom use as compared with the control group.

The results of this trial should not be taken to mean that all abstinence-only interventions are efficacious. This trial tested a theory-based abstinence-only intervention that would not meet federal criteria for abstinence programs and that is not vulnerable to many criticisms that have been leveled against interventions meeting federal criteria.19-20,36 It was not moralistic and did not criticize the use of condoms. Moreover, it had several characteristics associated with effective sexual risk-reduction interventions. It was theory-based and tailored to the target population based on qualitative data and included skill-building activities. It addressed the context of sexual activity and beliefs about the consequences of sexual involvement derived from the target population.

The limitations of this trial should also be considered. The data were based on self-reports, which can be inaccurate because of the failure of memory or socially desirable responding. As noted in the Methods section, we employed several procedures to increase the validity of self-reports. In addition, analyses were inconsistent with the view that social desirability response bias accounted for the results. The relatively small number of sexually active adolescents limited statistical power to test the effects of the safer-sex and comprehensive interventions on condom use. Therefore, effects of these interventions on condom use were likely under estimated in this trial. The generalizability of the results may be limited to African American grade 6 and 7 students willing to take part in a health promotion project on weekends. Whether the results would be similar with older adolescents or those of other races or in other countries is unclear.

Despite these limitations, the results of this randomized controlled trial are promising. They suggest that theory-based abstinence-only interventions can have positive effects on adolescents’ sexual involvement. This is important because abstinence is the only approach that is acceptable in some communities and settings in both the US and other countries. This trial showed that having had a theory-based abstinence-only intervention would not necessarily reduce adolescents’ condom use or motivation to use condoms. Nevertheless, the present results do not mean that abstinence-only intervention is the best approach or that other approaches should be abandoned. Theory-based abstinence-only interventions might be effective with young adolescents, but ineffective with older youth or people in committed relationships. For the latter, other approaches that emphasize limiting the number of sexual partners and using condoms, including the comprehensive interventions employed in this trial, might be more effective. Tackling the problem of STIs among young people requires an array of approaches implemented in a variety of venues. What the present results suggest is that theory-based abstinence-only interventions can be part of this mix. Employing theory-based abstinence-only interventions selectively might contribute to the overall goal of curbing the spread of STIs in both the US and other countries.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by research grant R01 MH062049 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). This article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH. The sponsor of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or the writing of the report. Some of the data reported in this article were presented at the XVI International AIDS Conference, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, August 14, 2006.

Footnotes

The authors appreciate the contributions of Sonya Combs, MS, Nicole Hewitt, PhD, Janet Hsu, BA, Gladys Thomas, MSW, MBA, and Dalena White, MBA and the statistical advice of Thomas Ten Have, PhD, MPH.

The corresponding author, J. Jemmott, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses. None of the authors has a conflict of interest regarding the research reported in this manuscript.

J. Jemmott contributed to the design and conceptualization of the trial, the data analysis and interpretation, the drafting of the article, and revising the article for critical content and approved the final manuscript.

L. Jemmott contributed to the design and conceptualization of the trial and revising the article for critical content and approved the final manuscript.

G. Fong contributed to the design and conceptualization of the trial and revising the article for critical content, and approved the final manuscript.

The research reported in this article was approved by Institutional Review Board #8 of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States. Approval Number: 387200.

Contributor Information

John B. Jemmott, III, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and Annenberg School for Communication Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America

Loretta S. Jemmott, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing Science Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America

Geoffrey T. Fong, University of Waterloo Department of Psychology and Ontario Institute for Cancer Research Waterloo, Ontario, Canada

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HIV/AIDS surveillance –general epidemiology (through 2005) Division of HIV/AIDS, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: [Downloaded on February 19, 2008]. Oct 23, 2007. atwww.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/general/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2006. Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: [Downloaded on February 22. 2008]. Nov, 2007. at http://www.cdc.gov/std/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention QuickStats: Pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates for teenagers aged 15–17 years---United States, 1976-2004. MMWR. 2005;54(04):100. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. [Downloaded June 6, 2007];Births: Final data for 2004. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2006 55(1):52. at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr55/nvsr55_01.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HIV/AIDS surveillance in adolescents and young adults (through 2005) Division of HIV/AIDS, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: [Downloaded on February 19, 2008]. Oct 23, 2007. at www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/adolescents/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller WC, Ford CA, Morris M, Handcock MS, Schmitz JL, Hobbs MM, Cohen MS, Harris KM, Udry JR. Prevalence of chlamydial and gonococcal infections among young adults in the United States. JAMA. 2004;291:2229–2236. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.18.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ventura SJ, Abma JC, Mosher WD, Henshaw SK. Health E-Stats. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: [Released December 2006. Downloaded June 6, 2007]. Recent trends in teenage pregnancy in the United States, 1990–2002. at www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/teenpreg1990-2002/teenpreg1990-2002.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaestle CE, Halpern CT, Miller WC, Ford CA. Young age at first sexual intercourse and sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(8):774–780. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buston K, Williamson L, Hart G. [20 September 2008];Young women under 16 years with experience of intercourse: who becomes pregnant? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007 61:221–225. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.044107. doi:10.1136/jech.2005.044107. Downloaded from jech.bmj.com on. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson F, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Concurrent sexual partnerships among African Americans in the rural south. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14:155–160. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandfort TGM, Orr M, Hirsch JS, Stantelli J. Long-term health correlates of timing of sexual debut: results from a National US study. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:155–161. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.097444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett SE, Assefi NP. School-based teenage pregnancy prevention programs: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.11.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson BT, Carey MP, Marsh KL, Levin KD, Scott-Sheldon LA. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for the human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents, 1985-2000: a research synthesis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(4):381–388. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirby D, Laris BA, Rolleri L. The impact of sex and HIV education programs in schools and communities on sexual behaviors among young adults. Family Health International, Youth Research Working Paper No. 2; Research Triangle Park: [Downloaded February 24, 2008]. 2006. at www.fhi.org/NR/rdonlyres/e4al5tcjjlldpzwcaxy7ou23nqowdd2xwiznkarhhnptxto4252pgco54yf4cw7j5acujorebfvpug/sexedworkingpaperfinalenyt.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African American adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;279:1529–1536. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stanton B, Li X, Ricardo I, Galbraith J, Feigelman S, Kaljee L. A randomized, controlled effectiveness trial of an AIDS prevention program for low-income African American youths. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:363–372. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290029004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coyle KK, Kirby DB, Marin BV, Gomez CA, Gregorich SE. Draw the line/respect the line: A randomized trial of a middle school intervention to reduce sexual risk behaviors. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:843–851. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Fong GT, McCaffree K. Reducing HIV risk-associated sexual behavior among African American adolescents: testing the generality of intervention effects. Am J Community Psychol. 1999;27:161–187. doi: 10.1007/BF02503158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Committee on Government Reform—Minority Staff . The content of federally funded abstinence-only education programs. United States House of Representatives; Washington, DC: Dec, 2004. Special Investigations Division. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santelli J, Ott MA, Lyon M, Rogers J, Summer D, Schleifer R. Abstinence and abstinence-only education: A review of U.S. policies and programs. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borawski E, Trapl ES, Lovegreen LD, Colabianchi N, Block T. Effectiveness of abstinence-only intervention in middle school teens. Am J Health Behavior. 2005;29(5):423–434. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2005.29.5.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Underhill K, Montgomery P, Operario D. [25 February 2008];Sexual abstinence only programmes to prevent HIV infection in high income countries: systematic review. BMJ. 2007 335:248. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39245.446586.BE. Downloaded from www.BMJ.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alan Guttmacher Institute . State policies in brief as of September 1, 2005: Sex and STD/HIV education. The Alan Guttmacher Institute; New York: 2005. www.guttmacher.org. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landry DJ, Kaeser L, Richards C. Abstinence promotion and the provision of information about contraception in public school district sexuality education policies. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31(6):280–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coates TJ, Szekeres G. A plan for the next generation of HIV prevention research: Seven key policy investigative challenges. Am Psychol. 2004;59(8):747–757. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandura A. Englewood Cliffs. Prentice-Hall; New Jersey: 1986. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. In: DiClemente R, Peterson J, editors. Preventing AIDS: Theories and methods of behavioral interventions. Plenum; New York: 1994. pp. 25–60. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior. Addison-Wesley; Boston: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Rand McNally; Chicago: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kauth MR, St. Lawrence JS, Kelly JA. Reliability of retrospective assessments of sexual HIV risk behavior: A comparison of biweekly, three-month, and twelve-month self-reports. AIDS Educ Prev. 1991;3:207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sudman S, Bradburn NM. Response effects in surveys. Aldine; Chicago: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crowne D, Marlowe D. The approval motive. Wiley; New York: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cummings P. The relative merits of risk ratios and odds ratios. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(5):438–445. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fontenberry DJ. The limits of abstinence-only in preventing sexually transmitted infections. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36:269–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trenholm C, Devaney B, Fortson K, Quay L, Wheeler J, Clark M. Impacts of four Title V, Section 510 abstinence education programs: Final report. Mathematica Policy Research, Inc; Princeton, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Underhill K, Operario D, Montgomery P. [September 22, 2008];Abstinence-only programs for HIV infection prevention in high-income countries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (Issue 4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005421.pub2. Art. No.: CD005421. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005421.pub2. Downloaded from http://mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD005421/pdf_fs.html. [DOI] [PubMed]