Abstract

Purpose

Our goals were to rigorously document and explore the interrelationships of various parameters in the aftermath of total knee arthroplasty (TKA), including patient characteristics, clinical scores, satisfaction levels, and patient-perceived improvements.

Materials and Methods

A questionnaire addressing sociodemographic factors, levels of satisfaction, and "wished-for" improvements was administered to 180 patients at least 1 year post primary TKA. Both satisfaction levels and wished-for improvements were assessed through nine paired parameters. Patients responded using an 11-point visual analogue scale (VAS) and the results were summarized as mean VAS score. Correlations between clinical scores and satisfaction levels and between satisfaction levels and desired improvements were analyzed.

Results

Patient satisfaction levels were only modest (mean score, 4-7) for eight of the nine parameters, including pain relief and restoration of daily living activities, the top two ranked parameters in wished-for improvement while high-flexion activity constituted the top source of discontent. Wished-for improvement was high in seven parameters, the top three being restoration of daily living activities, pain relief, and high-flexion activity. The effects of sociodemographic factors on satisfaction levels and wished-for improvement varied. Satisfaction levels correlated positively with functional outcomes, and satisfaction in pain relief and restoration of daily living activities correlated more often and most strongly with clinical scores.

Conclusions

Following TKA, patient satisfaction is not high for a number of issues, with improvements clearly needed in restoring daily living activities and relieving pain. Continued efforts to achieve better surgical outcomes should address patient-perceived shortcomings.

Keywords: Knee, Arthroplasty, Patient satisfaction, Improvement

Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a highly successful procedure that alleviates pain, improves physical function, and even promotes psychological well-being in patients with advanced Researchosteoarthritis (OA) of the knee1). However, even in the absence of noticeable complications and/or problems, a considerable proportion (range, 10% to 30%) of patients who underwent TKA reports dissatisfaction with their prosthetic knees2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9). Moreover, this rate of dissatisfaction has remained unchanged over the past years, despite substantial improvements in current surgical technique and implant design3,9).

As patient satisfaction has increasingly gained importance as a way of gauging treatment outcomes10) a number of studies have focused on discovering causes of dissatisfaction after TKA. In some studies, residual pain and functional disability were considered as the main reasons for dissatisfaction3,8,11,12). However, other studies reported preoperative patient expectations as important determinants of patient satisfaction3,6,7,13,14,15,16); and accordingly, various efforts have been made to improve patient outcomes by moderating preoperative expectations of TKA results3,11,17,18). Understanding patients' expectations of the procedure as well as their postoperative satisfaction is crucial to the success of TKA, and both should be accommodated in every aspect of the procedure, including patient education, implant choice, operative technique, and postoperative rehabilitation.

Unfortunately, prior studies of patient expectations and satisfaction in TKA have largely focused on overall satisfaction or issues related only to pain relief and functional activity. Thus, data on patient satisfaction in other aspects of TKA are limited. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, no information yet exists on postoperative perceptions (i.e., "wishes") for further improving the TKA experience, which may be of strategic value in this setting. Thus, this study was conducted 1) to rank nine parameters pertaining to satisfaction levels and wished-for improvement in patients after TKA, 2) to determine whether sociodemographic factors influence levels of patient satisfaction and wished-for improvement after TKA, 3) to explore associations between postoperative clinical scores and parameters scored by levels of patient satisfaction and wished-for improvement, and 4) to assess the relationship between patients' levels of satisfaction and wished-for improvement after TKA.

Materials and Methods

1. Study Design and Study Subjects

Patients who consecutively underwent TKA and visited outpatient clinic for follow-up between October of 2009 and December of 2009 were retrospectively evaluated. Variables examined were levels of patient satisfaction, wished-for improvements, and demographic/socioeconomic factors. Additionally, clinical outcomes were assessed at the time of follow-up, including the Western Ontario McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) score, American Knee Society (AKS) score, and Short Form-36 (SF-36) scores.

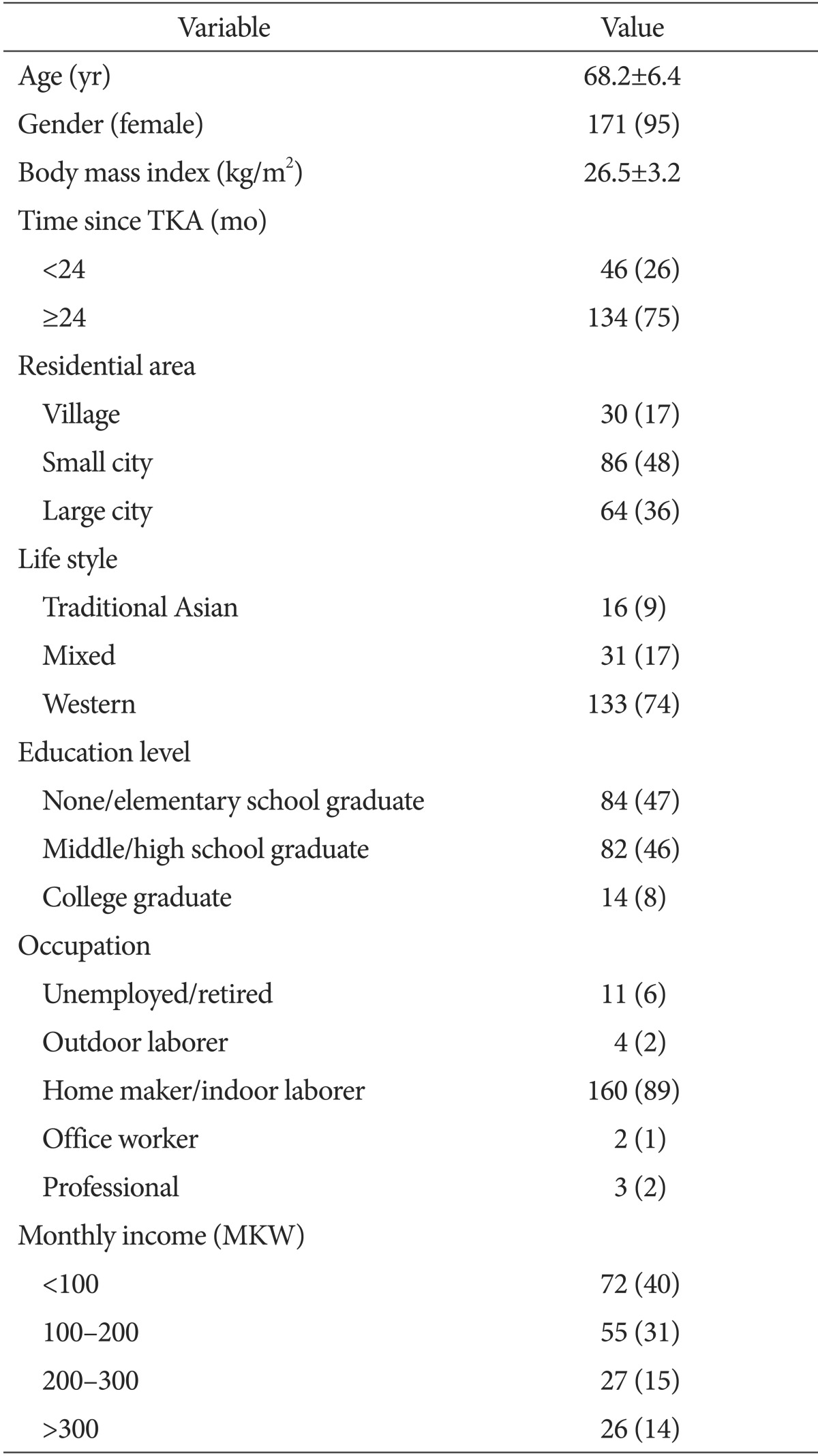

Included in the study were patients diagnosed with primary OA who underwent primary TKA at our institution (all performed by a single surgeon) with a minimum follow-up of 1 year. Exclusion criteria were the following: 1) refusal to participate; 2) incomplete questionnaire; 3) diagnosis other than primary OA; 4) revision TKA; 5) co-morbidities limiting activity of daily living (ADL), such as cerebrovascular or coronary artery disease, and Parkinson's disease; and 6) history of previous spinal or hip fractures and/or surgeries. Of 247 candidates in the specified timeframe, 67 patients were excluded (refusal to participate, 30; incomplete questionnaire, 7; and concomitant comorbidities, 30), leaving 180 patients who were qualified to participate. In this group, 171/180 (95%) were female with a mean age of 68.2±6.4 years, and mean body mass index (BMI) of 26.5±3.2 kg/m2 (Table 1). The average follow-up period was 2.6±1.2 years (range, 1 to 5 years).

Table 1. Demographics and Socioeconomic Features of Study Subjects.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

TKA: total knee arthroplasty, MKW: million Korean Won.

2. Perioperative and Postoperative Management

Medical clearance was granted 2-3 weeks prior to the day of scheduled TKA. Preoperative education was performed as part of medical clearance, informing patients of implant longevity; performance of ADL, including prohibition of deep flexion; participation level for recreational sports; operating cost; length of admission; naturally expected pain after TKA; and possible complications. Patients were also instructed on quadriceps setting (Q-set) and straight leg raise (SLR) exercises.

Necessary clinical procedures prior to the surgery were explained to all the patients undergoing TKA. Pre-emptive analgesia was given before surgery. Exposure was through a standard midline incision and medial parapatellar arthrotomy under tourniquet control. One of two posterior-stabilized implants [E-motion (B.Braun-Aesculap, Tuttlingen, Germany) or Genesis II (Smith & Nephew Inc., Memphis, TN, USA)] was generally used, and the patella was resurfaced in all cases. Fixation of all the implants was achieved with bone cement. A subcutaneous indwelling19) drain was placed in each instance, and subcuticular continuous suturing was used for skin closure. After surgery, patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) was given. Full extension exercise was started on the first postoperative day (POD), using range of motion exercise with continuous passive motion machine (CPM) after POD 2. Self-initiated Q-set and SLR exercises were encouraged immediately after surgery and ambulation was started after POD 2.

Postoperative standard follow-up visits were performed at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, and annually thereafter. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood cell (WBC) and differential counts were generally checked at 2 and 6 weeks postoperatively. Postoperative X-rays were taken at 6 weeks, 6 months, 1 year, and annually thereafter. Medications for pain management and other general symptoms were prescribed to patients upon their request.

3. Evaluation of Study Variables

Demographic and socioeconomic data, levels of patient satisfaction after TKA, and wished-for improvements in outcome were assessed using a three-part questionnaire (Appendix). Part 1 focused on demographic factors, namely, gender, age, time since TKA, and BMI; and socioeconomic factors, which were the highest level of education, occupation, place of residence, lifestyle, and monthly income. Parts 2 and 3 were aimed at evaluating patient satisfaction and wished-for improvements, pairing nine key parameters pertaining to TKA in two basic categories (i.e., the procedure itself and postoperative quality of life). This latter part of the questionnaire was based on the authors' experience of encountering patients who underwent TKA, identifying key factors related to patient status. Parameters related to the procedure included operating cost, perioperative complications, postoperative pain control, and incisional aesthetics. Those related to postoperative quality of life included pain relief, implant longevity, ADL restoration, performance of recreational sports, and performance of high-flexion activity. Wished-for improvements were described at the time of survey to patients as improvements to TKA that they thought possible. Patients responded using an an 11-point visual analogue scale (VAS) (range, 0 to 10), rating postoperative satisfaction from extremely dissatisfied (0) to extremely satisfied (10) and wished-for improvement from no wish at all (0) to sincere wish (10).

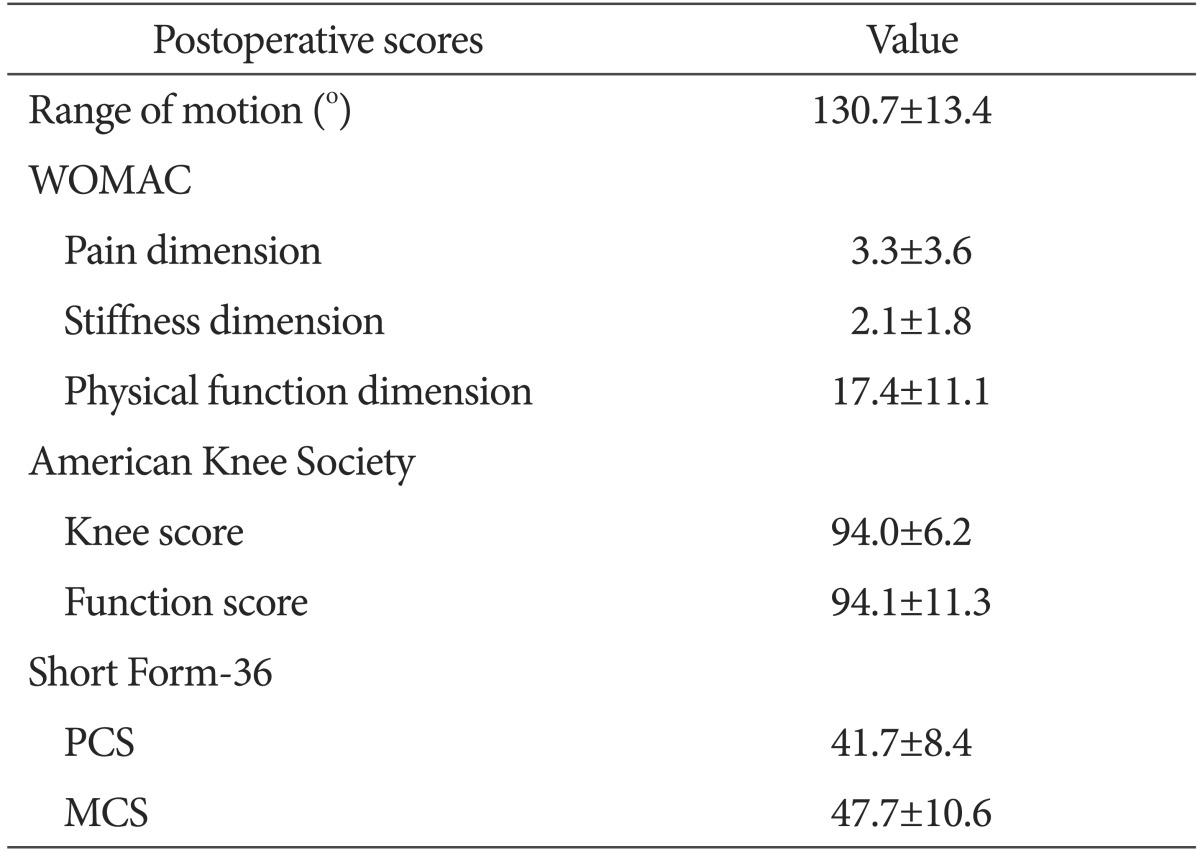

Clinical scores, including pain, stiffness, and physical function subscales of WOMAC, knee and function scores of AKS, and physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores of SF-36 were evaluated at the time of the survey (Table 2). All data from questionnaires and clinical scoring were collected by a single investigator (Kang).

Table 2. Postoperative Clinical Scores.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation.

WOMAC: Western Ontario McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index, PCS: physical component summary, MCS: mental component summary.

4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using standard software (SPSS ver. 20.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) with statistical significance set at p<0.05. Mean scores were calculated for each parameter of patient satisfaction and wished-for improvement after TKA, and ranking was decided by the calculated mean scores. Satisfaction level and wished-for improvement parameters were qualitatively categorized as low (0-3), moderate (4-7), and high (8-10); and for each parameter, categorical proportions were computed. To investigate relationships between patient characteristics (i.e., demographics and socioeconomic factors) and questionnaire parameters (both satisfaction level and wished-for improvement), each study variable was categorized into two groups: 1) age, young age (<65 years) vs. old age (≥65 years); 2) BMI, non-obese (BMI<25) vs. obese (BMI≥25); 3) time since TKA, short (<2 years) vs. long (≥2 years); 4) residential area, urban (large/small city) vs. rural; 5) lifestyle, Western vs. Traditional (traditional/mixed lifestyle); 6) highest level of education, low (middle school graduate or lower) vs. high (high school graduate or higher); 7) occupation, low demand (no occupation, professional occupation, office worker) vs. high demand (household, indoor/outdoor manual laborer); 8) monthly income, low (<2,000,000 KRW) vs. high (≥2,000,000 KRW). Differences in the parameter scores were assessed according to the categorized patient characteristics using the Mann-Whitney U test. Associations between postoperative clinical scores and parameter scores were examined through multiple linear regression analysis. Analysis was performed separately for each parameter using established qualitative subscales, due to a potentially high correlation among the parameter scores. In addition, potential confounds (gender, age, BMI, and unilateral vs. bilateral TKA) were controlled in all instances. Associations between satisfaction levels and wished-for improvements were also determined by multiple linear regression analysis, with potential confounds controlled as above.

Results

Ranking of questionnaire parameters differed by patient satisfaction level and wished-for improvement. In terms of satisfaction level, eight of the nine parameters had moderate-level mean scores (mean score, 4-7), and distributions varied by parameter. The top three variables in terms of satisfaction level were perioperative complications, relief from pain, and implant longevity, with the highest proportions of patients (69%, 46%, and 43%, respectively) reporting high-level satisfaction. On the other hand, perioperative pain control and high-flexion activity were the two lowest ranked parameters in satisfaction level, with the highest proportion of patients (40% and 55%, respectively) reporting low-level satisfaction. With respect to wished-for improvement, seven of the nine parameters showed high-level mean scores (mean score, 8-10). Highly ranked variables pertained to postoperative quality of life, whereas all procedural variables were ranked relatively low. The top three parameters in wished-for improvement were ADL restoration, relief from pain, and high-flexion activity, while incision aesthetics and operating cost were ranked as the two lowest (Table 3).

Table 3. Ranking of Parameters of Satisfaction and Wished-for Improvement with Corresponding Distributions.

Satisfaction levels and wished-for improvements are categorized as low (0-3), moderate (4-7), and high (8-10).

Periop: perioperative, ADL: activity of daily living.

a)All ranks based on the mean scores.

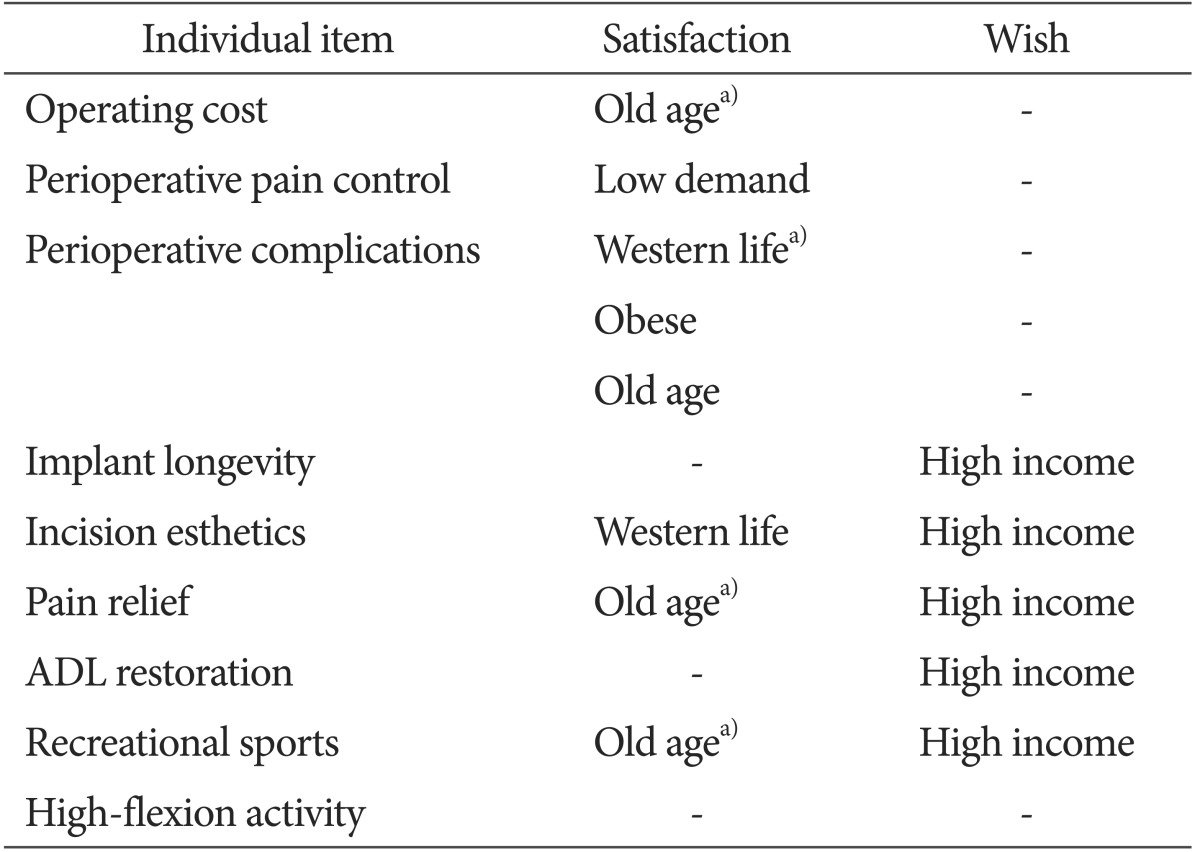

In comparing patient satisfaction and wished-for improvement according to the categorized patient characteristics, satisfaction level and wished-for improvement differed as well. Older patients reported higher satisfaction in four areas (operating cost, perioperative complication, pain relief, and recreational sports), patients with Western lifestyles showed higher satisfaction levels in two areas (perioperative complications and incision esthetics), and in obese patients, higher satisfaction was limited to one variable (perioperative complications). Of note, only patients with high income reported high-level scores on wished-for improvement in the following five areas: implant longevity, incision esthetics, pain relief, ADL restoration, and recreational sports (Table 4).

Table 4. Demographics and Socioeconomic Factors Associated with Higher Satisfaction Level and Wished-for Improvement.

Only patient characteristics showing statistical significance. p<0.05.

ADL: activity of daily living.

a)p<0.01.

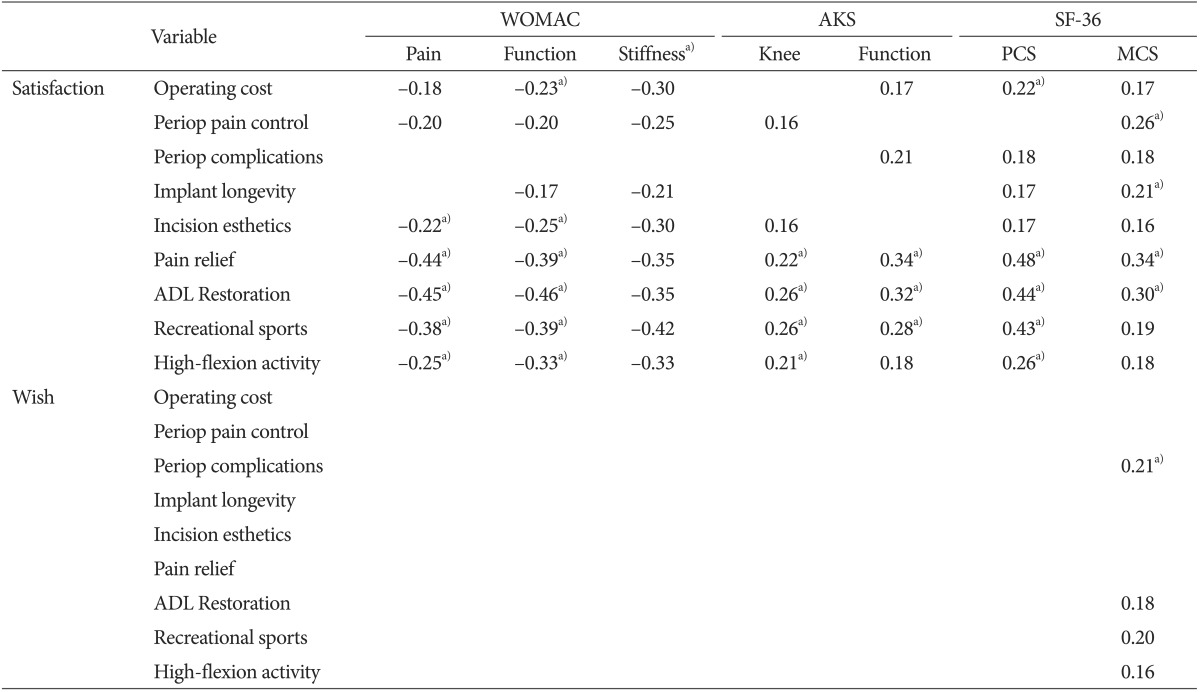

Analyses of relationships between clinical scores and questionnaire outcomes (satisfaction level and wished-for improvement), and between satisfaction level and wished-for improvement indicated a high level of correlation between clinical scores and patient satisfaction (but not wished-for improvement) and only limited association between satisfaction level and wished-for improvement. Patients with better clinical scores were more likely to report higher levels of satisfaction for most variables. However, WOMAC and AKS subscale scores, and SF-36 PCS scores did not correlate with wished-for improvement scores. Only the SF-36 MCS scores showed a positive correlation with wished-for improvement, namely for perioperative complications, ADL restoration, recreational sports, and high-flexion activity (Table 5). Also, a higher satisfaction level in ADL restoration correlated with higher wished-for improvement in ADL restoration (rs=0.16, p<0.05), whereas satisfaction in incision aesthetics showed a negative correlation with wished-for improvement in incision aesthetics (rs=-0.35, p<0.01).

Table 5. Associations of Various Clinical Scores with Questionnaire Parameters of Satisfaction and Wished-for Improvement.

Results given as rs; p<0.05 shown without footnote; p<0.01 shown with footnote.

WOMAC: Western Ontario McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index, AKS: American Knee Society, SF-36: Short Form-36, PCS: physical component summary, MCS: mental component summary, Periop: perioperative.

a)Spearman's rank correlation test with statistical significance.

Discussion

TKA is the most common surgical intervention for profound degenerative arthritis in senior patients. Despite substantial improvements after TKA, a considerable number of patients are still not satisfied with their outcomes, due to persistent pain, functional impairment, and unmet preoperative expectations3,6,8,14,15,16). In the current study, our goal was to investigate postoperative patient satisfaction in greater depth and document perceived therapeutic shortcomings after TKA. In doing so, the interrelationships of patient characteristics, various clinical scores, and scored questionnaire responses (post-TKA satisfaction level and wished-for improvement) were explored.

Several limitations should be noted when interpreting this study. First, validation of our questionnaire was not previously carried out. However, this study was not intended for comparisons of expectations or wishes within or between subjects, so validation was deemed unnecessary. Second, our study population was strictly Asian (Korean specifically), which may limit applicability of outcomes to the general population. Considering, however, that comparable levels of satisfaction in pain relief and functional activity have been recorded in Caucasian patients3,4), it may be assumed that general similarities exist. Third, the questionnaire used in the study made no distinction between unilateral or bilateral TKA. Generally, in patients undergoing unilateral TKA, the effect of the contralateral knee should be considered when evaluating function since the contralateral nonoperated knee influences patient function20). However, our purpose was an overall evaluation of post-TKA status, not a specific analysis of individualized knee. Fourth, the majority of the study sample was composed of elderly females, which further limits generalizability of the study. Nevertheless, TKA is typically performed on elderly subjects, and female dominance is universally observed21). Thus, our study population could be representative of the population at large in the setting of TKA. Fifth, the time interval since TKA surgical date varied. Still, most of our subjects were >2 years postoperative, which is similar to five- or ten-year status22), so any subsequent changes in clinical results would likely to have minimal effect on study outcomes.

The level of postoperative satisfaction was only modest for most of the parameters we surveyed, including pain relief and ADL restoration, which supports our initial premise. Furthermore, the mean satisfaction score and distribution of scores varied for each surveyed item. Mean scores ranged from 3.8-7.9, and the satisfaction level earning the highest proportion of respondents was used to establish ranking among the parameters. Compared with prior studies reporting relatively high satisfaction in most patients2,3,4,5,6,7,8), our findings indicate that satisfaction levels for individual parameters are not as favorable. Hence, there appears to be more room for improvement, even with generally good satisfaction; and a properly conducted, detailed assessment of each patient's satisfaction level is needed.

Our results also support the contention that patients have high-level concerns for improvements in multiple areas after TKA. Seven out of nine parameters showed high-level mean scores (>8.0) in terms of wished-for improvement, with all areas accruing the highest proportion of high-level respondents. Of note, highly ranked parameters all pertained to postoperative quality of life. As for wished-for improvements, ADL restoration (1st) and pain relief (2nd) were the highest ranked parameters, despite high rankings (4th and 2nd) in satisfaction level for these same variables. Consequently, a more effective postoperative management seems necessary to improve postoperative quality of life. Even though pain control and ADL restoration generated positive feedback, more attention should be given to these issues.

Of particular interest is the finding that high-flexion activity ranked lowest in satisfaction level among the study variables and was one of the highest ranked (3rd) wished-for improvements, reflecting its importance to patients after TKA. The pivotal nature of high-flexion activity in patients undergoing TKA is regularly mentioned23,24,25), although its priority is typically downplayed due to its decreasing effect on implant longevity26,27,28) and its relatively weak association with clinical scores, compared with pain relief and ADL restoration29,30). Although our data confirm a weak association between high-flexion activity and various clinical scores, perhaps re-prioritization is in order, given the low satisfaction level and high wish for its improvement. Yet, implant longevity was also ranked high as a wished-for improvement in our study; therefore, an implant allowing high flexion with safety is therefore a valid issue to consider in next-generation TKA systems.

As anticipated, patient satisfaction showed a positive correlation with functional outcomes. Satisfaction with pain relief and ADL restoration especially correlated with all clinical scores, and these correlations were stronger than those between other satisfaction variables and clinical scores, corresponding with a previous report8). Taking into account that pain relief and ADL restoration constituted the highest wished-for improvements in our group, these areas should be a major focus of patient care.

Wished-for improvements displayed a completely different relationship with patient characteristics than satisfaction level did. In contrast to our projections, there was a trend for patients with better clinical scores to strongly wish for improvements. The nature of correlations was also generally positive, signaling higher expectation in more satisfied patients. All of the above were contrary to our thinking, but these findings suggest that wished-for improvements and satisfaction level may diverge; in other words, the areas in which patients want to see most improvement are not readily predicted or endorsed by level of satisfaction or functional outcome. By the same token, the somewhat counterintuitive trend for patients with higher functional outcomes and higher satisfaction level to ask for improvements is worthy of note.

On a final note, incision aesthetics showed a negative correlation between satisfaction level and wish-for improvement, and the strength of correlation was the highest observed. Generally, the length of the incision range was 10 to 15 cm in our institute, but individualized cosmetic data (length, skin color, and skin contour) was not recorded. However, incision aesthetics was one of the lowest ranked items as a wished-for improvement, earning a moderate level of satisfaction, so it may be of only minor importance to patients. Because minimally invasive TKA is viewed as having a negative impact on implant longevity31), which outranks incision aesthetics as a wished-for improvement, an incision allowing adequate joint exposure is the preferred option.

Conclusions

Following TKA, patient satisfaction is not high for a number of issues, with improvements clearly needed especially in restoring ADL and relieving pain. Continued efforts to achieve better surgical outcomes should address patient-perceived shortcomings.

Appendix

Postoperative total knee arthroplasty (TKA) satisfaction and wish questionnaire.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Jones CA, Beaupre LA, Johnston DW, Suarez-Almazor ME. Total joint arthroplasties: current concepts of patient outcomes after surgery. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007;33:71–86. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim TK, Kwon SK, Kang YG, Chang CB, Seong SC. Functional disabilities and satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty in female Asian patients. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:458–464. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KD. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1119-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wylde V, Dieppe P, Hewlett S, Learmonth ID. Total knee replacement: is it really an effective procedure for all? Knee. 2007;14:417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandhi R, de Beer J, Petruccelli D, Winemaker M. Does patient perception of alignment affect total knee arthroplasty outcome? Can J Surg. 2007;50:181–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nilsdotter AK, Toksvig-Larsen S, Roos EM. Knee arthroplasty: are patients expectations fulfilled? A prospective study of pain and function in 102 patients with 5-year follow-up. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:55–56. doi: 10.1080/17453670902805007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noble PC, Conditt MA, Cook KF, Mathis KB. The John Insall Award: patient expectations affect satisfaction with total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;452:35–43. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000238825.63648.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson JG, Wixson RL, Tsai D, Stulberg SD, Chang RW. Functional outcome and patient satisfaction in total knee patients over the age of 75. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11:831–840. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(96)80183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robertsson O, Dunbar M, Pehrsson T, Knutson K, Lidgren L. Patient satisfaction after knee arthroplasty: a report on 27,372 knees operated on between 1981 and 1995 in Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:262–267. doi: 10.1080/000164700317411852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aspinal F, Addington-Hall J, Hughes R, Higginson IJ. Using satisfaction to measure the quality of palliative care: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42:324–339. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker PN, van der Meulen JH, Lewsey J, Gregg PJ National Joint Registry for England and Wales. The role of pain and function in determining patient satisfaction after total knee replacement Data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:893–900. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B7.19091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon SK, Kang YG, Kim SJ, Chang CB, Seong SC, Kim TK. Correlations between commonly used clinical outcome scales and patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:1125–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lingard EA, Sledge CB, Learmonth ID; Patient expectations regarding total knee arthroplasty: differences among the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1201–1207. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahomed NN, Liang MH, Cook EF, Daltroy LH, Fortin PR, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The importance of patient expectations in predicting functional outcomes after total joint arthroplasty. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1273–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourne RB, Chesworth B, Davis A, Mahomed N, Charron K. Comparing patient outcomes after THA and TKA: is there a difference? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:542–546. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1046-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brokelman R, van Loon C, van Susante J, van Kampen A, Veth R. Patients are more satisfied than they expected after joint arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74:59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisler T, Svensson O, Tengstrom A, Elmstedt E. Patient expectation and satisfaction in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:457–462. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.31245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mancuso CA, Graziano S, Briskie LM, Peterson MG, Pellicci PM, Salvati EA, Sculco TP. Randomized trials to modify patients' preoperative expectations of hip and knee arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:424–431. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0052-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seo ES, Yoon SW, Koh IJ, Chang CB, Kim TK. Subcutaneous versus intraarticular indwelling closed suction drainage after TKA: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2168–2176. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1243-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farquhar S, Snyder-Mackler L. The Chitranjan Ranawat Award: The nonoperated knee predicts function 3 years after unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:37–44. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0892-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crowninshield RD, Rosenberg AG, Sporer SM. Changing demographics of patients with total joint replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;443:266–272. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000188066.01833.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim YH, Choi Y, Kim JS. Comparison of a standard and a gender-specific posterior cruciate-substituting high-flexion knee prosthesis: a prospective, randomized, short-term outcome study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1911–1920. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kane RL, Saleh KJ, Wilt TJ, Bershadsky B. The functional outcomes of total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1719–1724. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noble PC, Gordon MJ, Weiss JM, Reddix RN, Conditt MA, Mathis KB. Does total knee replacement restore normal knee function? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(431):157–165. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000150130.03519.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss JM, Noble PC, Conditt MA, Kohl HW, Roberts S, Cook KF, Gordon MJ, Mathis KB. What functional activities are important to patients with knee replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;(404):172–188. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200211000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanekasu K, Banks SA, Honjo S, Nakata O, Kato H. Fluoroscopic analysis of knee arthroplasty kinematics during deep flexion kneeling. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:998–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee SY, Matsui N, Kurosaka M, Komistek RD, Mahfouz M, Dennis DA, Yoshiya S. A posterior-stabilized total knee arthroplasty shows condylar lift-off during deep knee bends. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(435):181–184. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000155013.31327.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagura T, Otani T, Suda Y, Matsumoto H, Toyama Y. Is high flexion following total knee arthroplasty safe?: evaluation of knee joint loads in the patients during maximal flexion. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:647–651. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miner AL, Lingard EA, Wright EA, Sledge CB, Katz JN; Knee range of motion after total knee arthroplasty: how important is this as an outcome measure? J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:286–294. doi: 10.1054/arth.2003.50046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park KK, Chang CB, Kang YG, Seong SC, Kim TK. Correlation of maximum flexion with clinical outcome after total knee replacement in Asian patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:604–608. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B5.18117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khanna A, Gougoulias N, Longo UG, Maffulli N. Minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40:479–489. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]