Abstract

Background

The orthopoxvirus strain Modified Vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) rapidly induces innate immune responses. Previously, we demonstrated that CCL2 and CCR1 are important players in MVA induced recruitment of leukocytes to the lung. Alveolar macrophages are sentinel cells in the lung, which are likely amongst the first cells of the immune system to encounter and respond to virus during respiratory infection. Therefore we examined the potential of the murine alveolar macrophage MH-S cell line as a model to study chemokine expression during infection with MVA and vaccinia virus (VACV) strain Western Reserve (WR).

Findings

MVA but not VACV infected MH-S cells increased the expression of the CXCR2 acting chemokine CXCL2. MH-S cells constitutively produced CCL2 and CCR1 acting chemokines CCL3, CCL5 and CCL9. Consequently, supernatants of mock treated and virus infected MH-S cells induced chemotaxis of murine promyelocyte MPRO cells and human monocytic THP-1 cells at the same level. However, supernatants of MVA infected MH-S cells significantly increased chemotaxis of the CCR2 deficient human monocytic cell line U-937. Chemotaxis of all three cell types was inhibited by J 113863, a CCR1 antagonist. Additionally, we show that MVA but not VACV WR infection of THP-1 cells induces expression of C-C motif and C-X-C motif chemokines and generates a chemotactic activity for monocytes, which was J 113863 sensitive.

Conclusions

These results extend our previous findings, demonstrating that MVA but not VACV WR induces chemokine production in alveolar macrophages and monocytes, which can induce recruitment of monocytes in a CCR1 dependent manner.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12985-015-0252-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Alveolar macrophage, CCR1, Chemotaxis, CXCR2, MH-S, MPRO, MVA, Neutrophil, THP-1, U937

Findings

Highly attenuated, replication deficient vaccinia strains such as Modified Vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) are increasingly used as viral vectors for the development of new vaccines. Intranasal inoculation is an attractive route of vaccination for delivery of MVA to mucosal tissue in the respiratory tract, which was found to be both safe and immunogenic in a phase I clinical trial [1]. A distinguishing feature of MVA is its ability to activate a robust innate immune response [2-4]. We recently showed that MVA triggers the production of chemokines in primary lung fibroblasts and bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) which induce chemotaxis of neutrophils [5].

Alveolar macrophages (AM) are permanent residents of the lung which are capable of exerting both pro- and anti-inflammatory immune responses. Due to their presence on the luminal surface of the respiratory system AM are likely amongst the first cells to encounter virus after respiratory infection. Indeed, it has been shown that AM help to control VACV infection, and their depletion exacerbates the host inflammatory response to viral infection, which is probably due to the increased viral burden [6]. However little is known about the early immune responses that is elicited in AM upon encounter with VACV or highly attenuated strains such as MVA. Activation of AM is tightly regulated by the local microenvironment, cell-cell interactions and soluble mediators that inhibit activation of pro-inflammatory signalling pathways, and removal of these signals leads to spontaneous activation of AM [7]. Consequently, our attempts to investigate cytokine expression in AM ex-vivo were largely unsuccessful due primarily to strong cytokine production in non-infected cells and rapid cell death of infected cells after isolation by bronchoalveolar lavage (data not shown). Therefore we tested the immortalized murine alveolar macrophage MH-S cell line [8] as a model system for MVA induced chemokine expression.

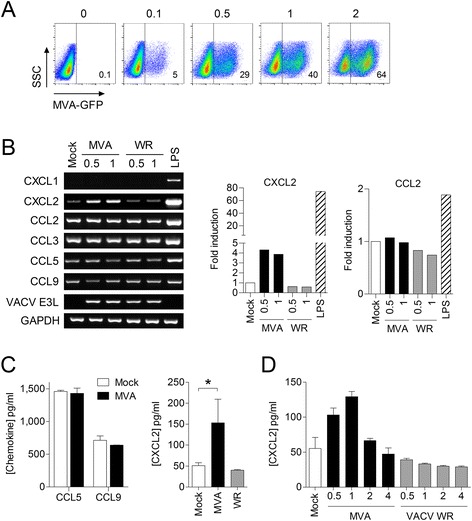

To determine whether MH-S cells are permissive to vaccinia virus infection and gene expression, cells were infected with MVA expressing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) under control of the P7.5 early/late promoter [9], and analysed using a MACSQuant VYB flow cytometer (Miltenyi Biotec). This showed that MH-S cells are readily infected with MVA and are permissive to viral gene expression (Figure 1A). Analysis by RT-PCR and ELISA showed that the CXCR2 ligand CXCL2 was induced by MVA but not by VACV WR in MH-S cells confirming our previous finding in primary murine lung fibroblasts [5]. Increased mRNA and protein levels of CXCL2 were detected at 8 h p.i., and the amount of CXCL2 produced depended on the MOI applied (Figure 1B, C and D). CXCL1 was only induced by LPS in MH-S cells, whereas CXCL5/6 (GCP-2/LIX), another neutrophils attracting chemokine [10], was not. Functionality of the GCP-2 specific PCR was demonstrated using RNA from murine alveolar epithelial MLE-12 cells treated with LPS or with supernatant from LPS challenged MH-S cells (Additional file 1).

Figure 1.

Murine alveolar macrophage MH-S cells produce neutrophil-attracting chemokines constitutively and after infection with MVA. A) MH-S cells were infected with MVA-GFP at the indicated MOI and infectivity was measured 16 h p.i. by flow cytometry. B) MH-S cells were infected with MVA or VACV WR at an MOI of 0.5 and 1, or challenged with LPS (1 μg/ml). Total RNA was isolated 8 h p.i. and investigated subsequently by specific RT-PCR as indicated. Fold induction of CXCL2 and CCL2 were calculated based on the intensity of PCR products using Image Lab 5.0 (Bio-Rad). Data from mock-treated cells were set to 1. C) Cell culture supernatants of MVA and VACV WR infected MH-S cells (1 MOI) were harvested 8 h p.i. and D) 16 h p.i., and chemokine concentrations determined by specific ELISA. Data are means ± SD and are representative of at least two independent experiments, *, P < 0.05; ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test.

Recently, we showed that CCR1 plays an important role in the recruitment of CD11b+Ly6Chi inflammatory monocytes into the lung [5]. Monocytes express the chemokine receptor CCR2 [11], and CCL2, a ligand for this receptor, has been shown to be important for MVA induced monocyte migration in vitro and in vivo [12]. However, monocytes are a heterogeneous population, and some subsets do not express CCR2 [13]. Moreover, CCR1 expression is up-regulated on differentiating monocytes, leading to increased sensitivity to CCR1 ligands whilst simultaneously decreasing sensitivity to CCR2 ligands [14]. Consequently, we asked whether CCR1 also plays a role in mediating MVA triggered monocyte chemotaxis.

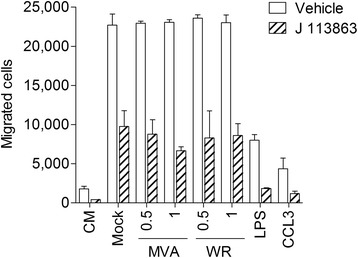

Unfortunately, the CCR1 ligands CCL3, CCL5 and CCL9, as well as the CCR2 ligand CCL2, were constitutively expressed in MH-S cells, and the levels were not increased by MVA or VACV WR infection (Figure 1B and C). Consequently, chemotaxis of murine promyelocyte MPRO cells was increased by supernatants from mock and virus infected MH-S cells to a similar level and decreased when MPRO cells were pre-incubated with the CCR1 antagonist J 113863 (Figure 2). Supernatants from LPS challenged MH-S cells induced less chemotaxis as compared to supernatants from mock infected cells. A possible explanation is that LPS-induced interleukin-10 in MH-S cells may have decreased the constitutive protein production of the C-C motif chemokines in a negative autocrine feedback loop [15,16].

Figure 2.

Supernatants from MH-S cells increase chemotaxis of murine promyelocyte MPRO cells in a CCR1 dependent manner. MPRO cells were tested for chemotaxis towards control medium (CM), human CCL3 (20 ng/ml) and supernatants from MH-S cells (16 h) challenged with LPS (1 μg/ml) or infected with MVA or VACV WR at an MOI as indicated using a 96-well Multi-Screen-MIC plate with a 5 μm pore-sized filter (Millipore). 75.000 cells were placed in the upper part and cells migrated into the lower part were counted after 3 h. Where indicated MPRO cells were pre-incubated with 20 nM of the CCR1 antagonist J 113863 for 5 min prior to running the assay. Data are means ± SD (n = 3).

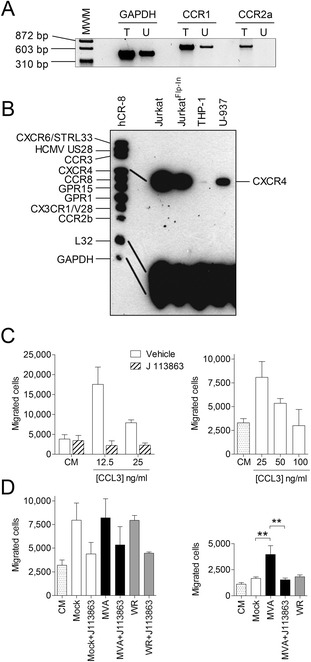

To avoid the masking effect of CCL2 when investigating MVA for its potential to induce a CCR1 dependent chemotactic activity in cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage we took advantage of the human monocytic cell line U-937, which, under our cell culture conditions, did not express CCR2 in contrast to human monocytic THP-1 cells (Figure 3A and B) [17]. Firstly, we tested whether supernatants from MH-S cells are also capable of inducing chemotaxis of THP-1 cells. This was possible since human chemokine receptors CCR1 and CCR2 can also be activated by the relevant murine ligands [18-20]. As with MPRO cells, supernatants from mock and virus infected MH-S cells increased chemotaxis of THP-1 at a similar level, which was decreased when THP-1 cells were pre-incubated with J 113863 (Figure 3D, left panel). Supernatants from MVA infected MH-S cells increased the chemotaxis of U-937 cells compared to supernatants from mock infected and VACV WR infected MH-S cells. Importantly, this chemotaxis of U-937 cells was significantly reduced when U-937 cells were pre-incubated with J 113863 (Figure 3D, right panel). Of note, J 113863 also acts on human CCR3 but this receptor was not expressed in either cell line (Figure 3B). Interestingly, despite the constitutive expression of CCR1 ligands by MH-S cells, levels of chemotaxis of U-937 towards culture supernatants of mock-infected cells were only slightly increased as compared to medium control (Figure 3D). This potentially indicates that other mechanisms induced by MVA may be required for optimal induction of cell migration.

Figure 3.

Supernatants from MVA but not VACV WR infected MH-S cells increase chemotaxis of U-937 cells in a CCR1 dependent manner. A) Total RNA from THP-1 cells (T) and U-937 cells (U) were isolated and used for GAPDH, CCR1 and CCR2 transcript variant A specific RT-PCR. B) Total RNA was isolated from cells as indicated and a multiprobe ribonuclease protection assay using hCR-8 (BD Biosciences) as probe was performed as previously described [12]. C) Verification of J 113863 to block CCR1 specific chemotaxis of THP-1 cells. Human CCL3 at concentrations as indicated was added to the lower part of a 96-well Multi-Screen-MIC plate with an 8 μm pore-sized filter (Millipore). 75.000 cells were placed in the upper part and cells migrated into the lower part were counted after 90 min. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). D) Human monocytic THP-1 cells (left panel) and U-937 cells (right panel) were tested for chemotaxis towards control medium (CM) and supernatants from mock, MVA or VACV WR infected MH-S cells (1 MOI, 16 h) as described in C). Where indicated, cells were pre-incubated with 5 nM of the CCR1 antagonist J 113863 for 5 min prior to running the assay. THP-1 cells and U-937 cells were allowed to migrate for 90 min and 30 min, respectively. Data are means ± SD (n = 3 for THP-1 cells; n = 6 for U-937 cells) and are representative of at least two independent experiments, **, P < 0.01; ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test.

In a recent study, we showed that complement component C5 is required for respiratory recruitment of neutrophils during MVA infection [21]. Surprisingly, complement component C3 was not necessary, which suggests the activation of an unknown proteolytic process by MVA. Indeed, CCL3 is N-terminally processed by CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV converting it to a very potent CCR1 ligand [22]. Taken together, in future studies it would be interesting to investigate whether an MVA activated protease plays a role in MVA triggered recruitment of monocytes and neutrophils.

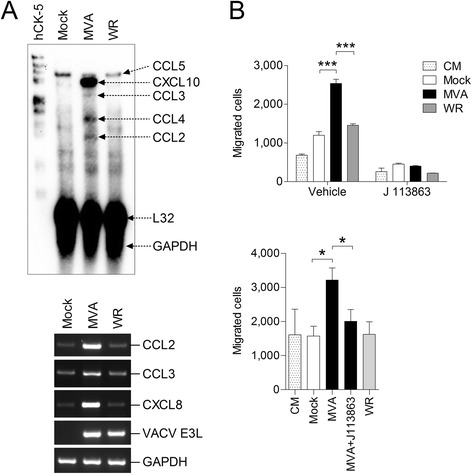

Previously we showed that MVA, but not VACV strain Elstree, induces chemokine expression including CCR1 acting chemokines in THP-1 cells [12]. Here we confirm our previous finding using multiprobe ribonuclease protection assay (RPA) and RT-PCR. Additionally we demonstrated that VACV WR does not induce chemokine expression in THP-1 cells (Figure 4A) and that supernatants from MVA but not VACV WR infected human monocytic THP-1 cells significantly increase chemotaxis of both naïve THP-1 cells and U-937 cells as compared to supernatants from mock infected cells (Figure 4B). As a side note, treatment of cells with the CCR1 antagonist J 113863 reduced background levels of THP-1 cell chemotaxis towards supernatants from mock infected cells and medium controls. This indicates that there was a CCR1 acting ligand present not only in supernatants of mock infected cells but also in the cell culture medium used. Indeed, constitutive expression of CCL5 in THP-1 cells was detected by multiprobe RPA, which may contribute to that effect (Figure 4A). Additionally, a bovine CCL3 isoform capable of inducing THP-1 chemotaxis in a CCR1 dependent manner has been detected in calf serum [23], and the cell culture medium used here for chemotaxis assays regularly contained 0.5% fetal calf serum.

Figure 4.

MVA, but not VACV WR, induces chemokine production in THP-1 cells and increases chemotaxis of monocytes in a CCR1 dependent manner. A) Total RNA from MVA or VACV WR infected THP-1 cells were isolated 6 hours p.i. and investigated subsequently by multiprobe ribonuclease protection assay using hCK-5 as probe (upper panel) and specific RT-PCR as indicated (lower panel). B) Chemotaxis of THP-1 cells (upper panel) and U-937 cells (lower panel) toward control medium (CM) and culture supernatants from THP-1 cells infected with MVA or VACV WR at 1 MOI for 16 hours. Where indicated, cells were treated with 5 nM of CCR1 antagonist J 113863 or the equivalent amount of solvent (all other samples) before running the assay as described in Figure 3. Data are means ± SD (n = 4). *, P < 0.05. ***, P < 0.001.

In summary, we demonstrated that MH-S cells can be used as model system to study MVA infection in alveolar macrophages but due to the high constitutive production of C-C motif chemokines only limited conclusions can be drawn from functional studies where the involvement of these proteins is relevant. Nevertheless, the results presented here confirm our recent findings in primary murine lung fibroblasts and bone marrow derived macrophages showing additionally that MVA, but not VACV WR, induces chemokine expression in cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage that is capable of inducing chemotaxis of neutrophils and monocytes.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF; TTU 07.803). MPRO cells were kindly provided by Dr. Adelheid Cerwenka (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum) and MH-S cells were kindly provided by Stephanie Konrad (Medical School Hannover).

Additional file

Verification of RT-PCR for murine CXCL5/GCP-2/LIX. As indicated, MLE-12 cells were challenged with LPS (1 μg/ml), with supernatants from MH-S cells (snMH-S) or with supernatants from LPS-treated MH-S cells (snMH-SLPS) for six hours and subsequently lysed for total RNA isolation. RNA was converted in cDNA and amplified using forward primer 5'-catttctgttgctgttcacg-3' and reverse primer 5'-atacatattccggagacaatgc-3'. Primers were designed using NCBI Reference Sequence: NM_009141.3; Mus musculus chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 (Cxcl5), mRNA. The CXCL5/GCP-2/LIX PCR product corresponded with the expected size of 617 bp. RT-PCR for murine GAPDH was performed as described (5). PCR without cDNA served as negative control. Lambda DNA Hind III/phiX174 DNA Hae III was used as molecular weight marker (MWM).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MHL conceived the study, designed experiments, performed experiments, analysed data and wrote the manuscript. PJRP performed experiments, analysed data and wrote the manuscript. CB performed experiments. GS analysed data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Michael H Lehmann, Email: Michael.Lehmann@lmu.de.

Philip JR Price, Email: Philip.Price@micro.vetmed.uni-muenchen.de.

Christine Brandmüller, Email: Christine.Brandmueller@micro.vetmed.uni-muenchen.de.

Gerd Sutter, Email: gerd.sutter@lmu.de.

References

- 1.Satti I, Meyer J, Harris SA, Thomas ZR, Griffiths K, Antrobus RD, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a candidate tuberculosis vaccine MVA85A delivered by aerosol in BCG-vaccinated healthy adults: a phase 1, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:939–46. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70845-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Royo S, Sainz B, Jr, Hernandez-Jimenez E, Reyburn H, Lopez-Collazo E, Guerra S. Differential induction of apoptosis, interferon signaling, and phagocytosis in macrophages infected with a panel of attenuated and nonattenuated poxviruses. J Virol. 2014;88:5511–23. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00468-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dai P, Wang W, Cao H, Avogadri F, Dai L, Drexler I, et al. Modified vaccinia virus Ankara triggers type I IFN production in murine conventional dendritic cells via a cGAS/STING-mediated cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003989. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Price PJ, Torres-Dominguez LE, Brandmuller C, Sutter G, Lehmann MH. Modified Vaccinia virus Ankara: innate immune activation and induction of cellular signalling. Vaccine. 2013;31:4231–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price PJ, Luckow B, Torres-Dominguez LE, Brandmuller C, Zorn J, Kirschning CJ, et al. Chemokine (C-C Motif) Receptor 1 Is Required for Efficient Recruitment of Neutrophils during Respiratory Infection with Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara. J Virol. 2014;88:10840–50. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01524-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivera R, Hutchens M, Luker KE, Sonstein J, Curtis JL, Luker GD. Murine alveolar macrophages limit replication of vaccinia virus. Virology. 2007;363:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snelgrove RJ, Goulding J, Didierlaurent AM, Lyonga D, Vekaria S, Edwards L, et al. A critical function for CD200 in lung immune homeostasis and the severity of influenza infection. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1074–83. doi: 10.1038/ni.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mbawuike IN, Herscowitz HB. MH-S, a murine alveolar macrophage cell line: morphological, cytochemical, and functional characteristics. J Leukoc Biol. 1989;46:119–27. doi: 10.1002/jlb.46.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staib C, Lowel M, Erfle V, Sutter G. Improved host range selection for recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara. Biotechniques. 2003;34:694–6. doi: 10.2144/03344bm02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proost P, De Wolf-Peeters C, Conings R, Opdenakker G, Billiau A, Van Damme J. Identification of a novel granulocyte chemotactic protein (GCP-2) from human tumor cells. In vitro and in vivo comparison with natural forms of GRO, IP-10, and IL-8. J Immunol. 1993;150:1000–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mack M, Cihak J, Simonis C, Luckow B, Proudfoot AE, Plachy J, et al. Expression and characterization of the chemokine receptors CCR2 and CCR5 in mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:4697–704. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehmann MH, Kastenmuller W, Kandemir JD, Brandt F, Suezer Y, Sutter G. Modified vaccinia virus ankara triggers chemotaxis of monocytes and early respiratory immigration of leukocytes by induction of CCL2 expression. J Virol. 2009;83:2540–52. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01884-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–64. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufmann A, Salentin R, Gemsa D, Sprenger H. Increase of CCR1 and CCR5 expression and enhanced functional response to MIP-1 alpha during differentiation of human monocytes to macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:248–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meng A, Zhang X, Shi Y. Role of p38 MAPK and STAT3 in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated mouse alveolar macrophages. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8:1772–6. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berkman N, John M, Roesems G, Jose PJ, Barnes PJ, Chung KF. Inhibition of macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha expression by IL-10. Differential sensitivities in human blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 1995;155:4412–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lehmann MH, Masanetz S, Kramer S, Erfle V. HIV-1 Nef upregulates CCL2/MCP-1 expression in astrocytes in a myristoylation- and calmodulin-dependent manner. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4520–30. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gladue RP, Cole SH, Roach ML, Tylaska LA, Nelson RT, Shepard RM, et al. The human specific CCR1 antagonist CP-481,715 inhibits cell infiltration and inflammatory responses in human CCR1 transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2006;176:3141–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarafi MN, Garcia-Zepeda EA, MacLean JA, Charo IF, Luster AD. Murine monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-5: a novel CC chemokine that is a structural and functional homologue of human MCP-1. J Exp Med. 1997;185:99–109. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schall TJ, Simpson NJ, Mak JY. Molecular cloning and expression of the murine RANTES cytokine: structural and functional conservation between mouse and man. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1477–81. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price PJ, Banki Z, Scheideler A, Stoiber H, Verschoor A, Sutter G, et al. Complement Component C5 Recruits Neutrophils in the Absence of C3 during Respiratory Infection with Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara. J Immunol. 2015;194:1164–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Proost P, Menten P, Struyf S, Schutyser E, De Meester I, Van Damme J. Cleavage by CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV converts the chemokine LD78beta into a most efficient monocyte attractant and CCR1 agonist. Blood. 2000;96:1674–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Buck M, Gouwy M, Proost P, Struyf S, Van Damme J. Identification and characterization of MIP-1alpha/CCL3 isoform 2 from bovine serum as a potent monocyte/dendritic cell chemoattractant. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:789–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]