Abstract

Objectives

We tested the efficacy of a school-based HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention for South African adolescents.

Design

A cluster-randomized controlled design, with assessments of self-reported sexual behavior collected pre-intervention and 3, 6, and 12 months post-intervention.

Setting

Primary schools in a large Black township and a neighboring rural settlement in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa.

Participants

9 of 17 matched-pairs of schools were randomly selected. Grade 6 learners with parent/guardian consent were eligible.

Interventions

Two 6-session interventions based on behavior-change theories and qualitative research: HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention targeted sexual-risk behaviors; attention-matched health-promotion control intervention targeted health issues unrelated to sexual behavior.

Main Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was self-report of unprotected vaginal intercourse in the previous 3 months averaged over the 3 follow-ups. Secondary outcomes were other sexual behaviors.

Results

A total of 1,057 (94.5%) of 1,118 eligible learners (mean age = 12.4 years) participated, with 96.7% retained at the 12-month follow-up. Generalized estimating equations analyses, adjusting for clustering from 18 schools, revealed that averaged over the 3 follow-ups a significantly smaller percentage of HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention participants reported having unprotected vaginal intercourse (OR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.30-0.85), vaginal intercourse (OR = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.42-0.94), and multiple sexual partners (OR = 0.50; 95% CI, 0.28-0.89), when adjusted for baseline prevalences, compared with health-promotion control participants.

Conclusions

This is the first large-scale community-level randomized intervention trial to obtain significant effects on HIV/STD sexual-risk behavior among South African adolescents in the earliest stages of entry into sexual activity.

South Africa has the largest number of persons living with HIV/AIDS in the world, an estimated 5,500,000.1-2 About 18.8% of South Africans aged 15 to 49 years are living with HIV,3 and new HIV infections are being driven by the high incidence in those aged 15 to 24 years. It is estimated that more than one-half of all South African 15-year olds in 2006 will not survive to age 60 years.4 Young adolescents, before or just after the initiation of sexual activity, are singularly important for intervention, because they are highly vulnerable and because they have not established habitual patterns of sexual behavior.

Studies in the US have identified efficacious sexual risk-reduction interventions for adolescents.5-7 However, few randomized controlled trials of interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa have had follow-up periods as long as 12 months post intervention.8-12 Other studies conducted with adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa used quasi-experimental designs, had very brief follow-up periods, suffered significant loss at follow-up, or obtained nonsignificant intervention effects on behavior.13-16

Here we report a cluster-randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of an HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention compared with a health-promotion control intervention among grade 6 learners in schools in Mdantsane, a large Black township, and Berlin, a neighboring rural settlement, in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Eighteen schools, matched in pairs, were randomly selected and then randomized to 1 of the 2 interventions. We hypothesized that fewer participants in the HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention compared with the health-promotion control intervention would report unprotected vaginal intercourse during a 12-month follow-up period.

METHODS

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) #8 at the University of Pennsylvania, which was the designated IRB under the federalwide assurances of the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Fort Hare, reviewed and approved the study. The IRB at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention deferred approval to the IRB at University of Pennsylvania. The study was conducted in Mdantsane, an urban township (population 177,816), and Berlin (population 2,271) a neighboring rural settlement, near East London in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa, where Xhosa is the first home language for 95.1% of the population.17 The apartheid regime created Mdantsane, the second largest South African township after Soweto, as living space for cheap African labor. Schools that taught grade 6 learners and served the general population of learners were eligible to participate. There were 36 primary schools in Mdantsane and Berlin. One school for children with learning disabilities was ineligible, leaving 35 eligible schools: 26 in Mdantsane and 9 in Berlin. All 35 eligible schools agreed to participate in the trial. We created 17 matched pairs of schools that had similar numbers of grade 6 learners, classrooms, and classrooms with electricity—a proxy for poverty. We matched urban and rural schools separately. From the 17 matched pairs, we randomly selected 9 pairs: 7 pairs comprised of urban schools; 2 comprised of rural schools.

We utilized a cluster-randomized controlled trial design. Within each pair, using computer-generated random number sequences, we randomized 1 school to the HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention and the other to the health-promotion-control intervention using concealment of allocation techniques designed to minimize bias in assignment in randomized clinical trials. The Biostatistician in Philadelphia conducted the computer-generated random assignments; the Project Director in East London, South Africa implemented the assignments. We enrolled the schools into the trial during a 13-month period beginning in October 2004, with all data collection completed by December 2006.

To recruit participants, Xhosa-speaking community members made announcements at the selected schools and distributed letters and consent forms for parents/guardians to all grade 6 learners. At the time of recruitment, school administrators, potential participants, and recruiters were blind to the specific intervention to which the school had been randomized, and recruiters followed a common standardized scripted recruitment procedure at all schools. At 12 schools, grade 6 learners who had written parent/guardian consent were eligible to participate. At 6 schools, where there were too few classrooms to accommodate all learners who had consent, we randomly selected learners as eligible from among those with consent.

We held the intervention and data-collection sessions at the learners’ schools during the extracurricular period at the end of the school day. Participants completed confidential questionnaires before and 3, 6, and 12 months after the intervention. Learners who completed the pre-intervention questionnaire and attended Session 1 of the intervention were enrolled into the trial. Participants were compensated with a notebook, a pen, and a pencil for the 3-month follow-up; a t-shirt for the 6-month follow-up; and a backpack for the 12-month follow-up.

Interventions

The interventions were developed based on social cognitive theory,18 the theory of planned behavior,19 and extensive formative research or “targeted ethnography.”20 We conducted 9 focus groups with 89 Xhosa-speaking grade-6 learners, 4 focus groups with 34 parents of grade-6 Xhosa-speaking learners, and 1 focus group with 12 teachers of such learners in Mdantsane and Berlin.

Both interventions consisted of 12 1-hour modules, with 2 modules delivered during each of 6 sessions on 6 consecutive school days. Both interventions were highly structured and implemented in mixed-sex small groups by male and female adult Xhosa-speaking co-facilitator pairs using standardized intervention manuals. We conducted 3 pilot tests of the interventions with 116 grade 6 learners. The interventions were pilot tested in English in Mdantsane, translated into Xhosa, back-translated from Xhosa to English, pilot tested in Xhosa in Mdantsane and Berlin, and delivered in Xhosa in the main trial. Both interventions included interactive exercises, games, brainstorming, role-playing, and group discussions. The mixed-sex groups allowed inclusion of single-sex activities led by the same-sex facilitators. Electricity was not available in many of the classrooms; consequently, we could not utilize video, an often-used strategy in efficacious interventions. We, therefore, used comic workbooks—6 issues, 1 for each session—using a series of characters and storylines to address issues that we had learned during the formative research phase were important aspects of participants’ lives relevant to the targeted behaviors.

We designed the HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention to (a) increase HIV/STD risk-reduction knowledge, (b) enhance behavioral beliefs19 that support abstinence and condom use, and (c) increase skills and self-efficacy18-19 to negotiate abstinence and condom use and to use condoms. To facilitate cross-generational discussions of sexual matters, which formative research had revealed were very difficult for parents and children, we gave the learners homework assignments to complete with a parent or caregiver. In addition, because girls in South Africa are vulnerable to rape and other aspects of male domination,21-22 sex-specific modules addressed sexuality, sexual maturation, appropriate sex roles, and rape myth beliefs.

The health-promotion intervention was designed to control for nonspecific features, including group interaction and special attention.23 It contained activities similar to the HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention, but focused on behaviors linked to risk of heart disease, hypertension, stroke, diabetes, and certain cancers—leading causes of morbidity and mortality among South Africans.24-26 It was designed to increase fruit and vegetable consumption and physical activity and decrease cigarette smoking and alcohol use.

The co-facilitators were 43 adults (21 women and 22 men) 27 to 56 years of age (mean = 42 years) from the community who were bilingual in English and Xhosa. Their median education was a Bachelor’s degree; 65% had worked as teachers, and 63% had previously taught HIV education. The process of selecting them involved oral and performance-based interviewing. We randomly assigned them to an 8-day training to implement 1 of the 2 interventions. In this way, we randomized facilitators’ characteristics across interventions.5 During the training, the trainers modeled the intervention activities and the facilitators learned their assigned intervention, practiced implementing it, received feedback, and created common responses to potential issues that might arise during implementation. The importance of fidelity to the intervention was emphasized.

Assessments

Assessments were conducted before, immediately post, and 3, 6, and 12 months post-intervention via confidential questionnaires that were written in Xhosa following translation and back-translation from English. We pilot tested the questionnaire with 64 grade 6 learners from Mdantsane and Berlin. Adults from the community who were bilingual in Xhosa and English and blind to the participants’ intervention assignment implemented a read-aloud procedure: Learners completed questionnaires at their desks while data collectors read the questions aloud. Data collectors received a 2-day training that included modeling of data-collection procedures and practice with performance feedback.

The primary outcome was report of unprotected vaginal intercourse measured using the question, “In the past three months, on how many days did you have vaginal intercourse without using a condom?” Vaginal intercourse was defined as “your penis in a female’s vagina” (male version) or “a boy’s penis in your vagina” (female version). Participants’ responses were coded “1” if they did not have vaginal intercourse without using a condom and “2” if they did have vaginal intercourse without using a condom. Secondary outcomes included sexual experience and recent vaginal intercourse, heterosexual anal intercourse, and multiple partners. Sexual experience was assessed using the question “Have you ever had vaginal intercourse?” Questions regarding recent sexual activity used a 3-month reporting period. Recent vaginal intercourse was assessed using the appropriate sex-specific item, “In the past three months, did you have vaginal intercourse with a female (male)?” Similarly, recent heterosexual anal intercourse was assessed using the item, “In the past three months, have you had anal intercourse with a female?” (male version). Anal intercourse was defined using the term “anus/behind.” Having multiple partners was measured using the question, “In the past three months, how many females (male version) have you had vaginal intercourse with?” Participants’ responses were coded “1” if they had fewer than 2 partners and “2” if they had 2 or more partners.

We took several steps to increase the validity of self-reported sexual behavior. To facilitate the learners’ ability to recall, we asked them to report their behaviors during a brief period (i.e., past 3 months),27 wrote the dates comprising the period on a chalkboard, and gave them calendars clearly highlighting the period. We stressed the importance of responding honestly, informing them that their responses would be used to create programs for other Xhosa-speaking adolescents like themselves and that we could do so only if they answered the questions honestly. We assured the participants that their responses would be kept confidential and that code numbers rather than names would be used on the questionnaires. Participants signed an agreement pledging to answer the questions honestly, a procedure that has been shown to yield more valid self-reports regarding sensitive issues.28

Sample size and Statistical Analysis

The a priori unit of inference in this trial was the individual. A sample size calculation was performed to detect an a priori effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.25 on unprotected intercourse, adjusting for the expected variance inflation due to clustering.29 We chose d = 0.25 based on a meta-analysis of HIV risk-reduction intervention studies30 because, at the study’s onset, no data were available on which to base an effect-size estimate specific to the study population. Based on pilot data, we estimated an intraclass correlation (ICC) of 0.00864. Assuming alpha = 0.05, a 2-tailed test, ICC = 0.00864, d = 0.25, 20% attrition at 12-month follow-up, and N = 1,100 grade-6 learners enrolled in the trial from 16 schools with an average of 67 learners in each school, the trial was estimated to have 80% power to detect d = 0.25 effect of the intervention.

Later we decided to match schools in pairs and randomize them to interventions, although we ignored the pairing in the analyses because of the small number of pairs.31-32 Before analyzing intervention efficacy, we used chi-square and t tests to analyze attrition. In the primary analyses, the efficacy of the HIV/STD intervention compared with the health-promotion control intervention over the 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups was tested using generalized estimating equation (GEE) models, properly adjusting for longitudinal repeated measurements on learners clustered within schools.33-34 The models were fit and contrast statements were specified to obtain estimated odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Robust standard errors were ed and an exchangeable working correlation matrix was specified. The models included time-independent covariates, baseline measure of the criterion, intervention condition, and time (3 categories representing 3-, 6-, 12-month follow-up). However, analyses of sexual debut did not control for baseline because it was restricted to those sexually inexperienced at baseline. We report estimated average intervention effects over the 3 follow-ups constructed from appropriate ‘estimate’ statements from fitted GEE models and ds, calculated by transforming the odds ratios using the Cox transformation.35 Models assessing whether the efficacy of the intervention differed among the 3 follow-ups included the baseline measure of the criterion, intervention condition, time, and the Intervention-Condition x Time interaction.

We had intended to examine self-reported consistent condom use as a secondary outcome, but too few participants reported sexual intercourse at baseline to allow for meaningful analyses of changes over time in condom use. Also, because of the low percentage of participants who reported sexual intercourse, we examined binary measures rather than counts of sexual behaviors in the previous 3 months. Analyses were performed using an intent-to-treat mode with participants analyzed based on their intervention assignment, regardless of the number of intervention or data-collection sessions attended. These analyses were completed using SAS V9.

We conducted analyses of school-level intervention effects to confirm the robustness of our findings from individual-level analyses. We used meta-analysis methods36 that allowed us to take into account the number of learners in each pair of schools, giving more weight to larger pairs, similar to weighing larger studies more than smaller studies in a meta-analysis. This analytic approach also allowed us to examine whether the intervention effect size varied among the pairs of schools, just as a meta-analyst might test whether effect sizes were heterogeneous among trials. After fitting GEE models as previously described, we constructed mean estimated proportions for each outcome for each school (n=18). We treated the estimated intervention difference for each pair as a ‘study’ and constructed corresponding pooled estimates of intervention differences and 95% confidence intervals based on the 9 pairs using the ‘metan’ command in STATA V10, assigning weights to each pair proportional to the size of schools within pairs. Finally, we constructed an 8 degree-of-freedom test of whether intervention effects were heterogeneous across pairs.

Role of the Funding Source

The sponsors of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or the writing of the report.

RESULTS

Of the 1,898 grade-6 learners enrolled at the schools, 1,396 or 73.6% returned signed consent forms, 1,118 were eligible to participate, and 1,057 or 94.5% participated. Table 1 shows that 558 girls and 499 boys participated. Their age ranged from 9 to 18 years, with a mean (SD) of 12.4 (1.2); 7.6% resided in Berlin, and the others resided in Mdantsane. Only 38.8% lived in a household with their father.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participating Schools and Grade 6 Learners by Intervention Condition at Baseline, Mdantsane and Berlin, South Africa 2004-2005.

| HIV/STD Intervention |

Health Control Intervention |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | |||

| School characteristics at baseline | |||

| No. | 9 | 9 | 18 |

| No. Rural | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| No. Urban | 7 | 7 | 14 |

| Mean (SD) No. Classrooms | 9.7 (3.2) | 8.9 (2.7) | 9.3 (2.9) |

| Mean (SD) No. Classrooms with Electricity |

5.6 (5.8) | 3.3 (3.8) | 4.4 (4.9) |

| No. grade 6 learners enrolled | 940 | 958 | 1,898 |

| No. (%) returned signed consent | 702 (74.7%) | 694 (72.4%) | 1,396 (73.6%) |

|

| |||

| Participant characteristics at baseline | |||

| No. | 562 | 495 | 1,057 |

| No. (%) Female | 306/562 (54.5%) | 252/495 (50.9%) | 558/1,057 (52.8%) |

| No. (%) Father present in household | 203/544 (37.3%) | 194/479 (40.5%) | 397/1,023 (38.8%) |

| No. (%) Rural resident | 41/562 (7.3%) | 39/495 (7.9%) | 80/1,057 (7.6%) |

| No. (%) Age (years) group | |||

| 9-11 | 144/562 (25.6)% | 104/495 (21.0%) | 248/1,057 (23.5%) |

| 12-13 | 330/562 (58.7%) | 304/495 (61.4%) | 634/1,057 (60.0%) |

| 14-18 | 88/562 (15.7%) | 87/495 (17.6%) | 175/1,057 (16.6%) |

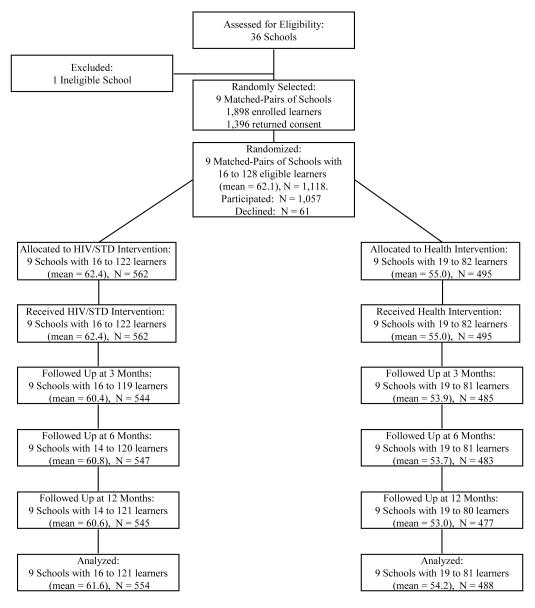

As shown in Figure 1, all 18 schools remained in the trial to its completion. All participants attended intervention session 1; attendance at sessions 2 through 6 ranged from 97.0% to 98.6%. Follow-up return rates were excellent: 1,029 (97.4%) completed the 3-month follow-up, 1,030 (97.4%) completed the 6-month follow-up, 1,022 (96.7%) completed the 12-month follow-up, and 1,043 (98.7%) attended at least 1 follow-up. The percentage that attended at least 1 follow-up did not differ between the HIV/STD risk-reduction (98.8%) and control interventions (98.6%). Attending a follow-up session was unrelated to sex, father’s presence in the household, residing in Berlin, or sexual behavior. However, participants aged 14 to 18 years (96.0%) were less likely to return for follow-up than were those aged 12 to 13 years (99.2%) or 9 to 11 years (99.2%), p = 0.003.

Figure 1.

Progress of participating schools and grade 6 learners through the trial, Mdantsane and Berlin, South Africa 2004-2006. Learners who were not followed up failed to attend the scheduled follow-up sessions or make-up sessions for unknown reasons.

Effects of the HIV/STD Risk-Reduction Intervention

Primary Outcome

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for sexual behaviors by intervention condition and assessment period. Table 3 presents estimated intervention effects during the follow-up period, corresponding significance tests (both unadjusted and adjusted for baseline outcome), and ICCs. A smaller percentage of participants in the HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention schools reported having unprotected vaginal intercourse in the past 3 months averaged over follow-up (2.22%) compared with their counterparts in health-promotion-control schools (4.24%), controlling for baseline unprotected vaginal intercourse (p = 0.0125; d=0.41).

Table 2.

Observed Percentages Reporting Sexual Behaviors, HIV/STD Knowledge, and Self-Efficacy Outcomes by Intervention Condition and Assessment Period, Mdantsane and Berlin, South Africa 2004-2006.

| Outcomes | Baseline | 3-month | 6-month | 12-month | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV/STD Intervention N=562 |

Health Intervention N=495 |

HIV/STD Intervention N=544 |

Health Intervention N=485 |

HIV/STD Intervention N=547 |

Health Intervention N=483 |

HIV/STD Intervention N=545 |

Health Intervention N=477 |

|

| Unprotected vaginal intercourse in the past 3 months |

4/561 (0.71) | 3/495 (0.61) | 9/543 (1.66) | 20/485 (4.12) | 14/545 (2.57) | 20/482 (4.15) | 12/545 (2.20) | 21/477 (4.40) |

| Vaginal intercourse in the past 3 months |

7/560 (1.25) | 5/495 (1.01) | 18/543 (3.31) | 35/485 (7.22) | 31/547 (5.67) | 33/482 (6.85) | 27/545 (4.95) | 37/476 (7.77) |

| Multiple sexual partners in the past 3 months |

4/560 (0.71) | 1/494 (0.20) | 8/544 (1.47) | 18/484 (3.72) | 12/546 (2.20) | 16/482 (3.32) | 9/544 (1.65) | 13/476 (2.73) |

| Sexually in-experienced | 533/557 (95.7) | 481/492 (97.8) | 459/544 (84.4) | 414/485 (85.4) | 433/547 (79.2) | 391/483 (81.0) | 418/545 (76.7) | 367/477 (76.4) |

| Anal intercourse in the past 3 months |

3/561 (0.53) | 4/495 (0.81) | 9/544 (1.65) | 15/484 (3.10) | 5/547 (0.91) | 14/483 (2.90) | 17/545 (3.12) | 20/476 (4.20) |

Table 3.

GEE Empirical Significance Tests and Effect Size Estimates for the Overall Intervention Effect (3-, 6-, and 12-month Follow-up Assesments) Unadjusted for Baseline Prevalence and Adjusted for Baseline Prevalence, Mdantsane and Berlin, South Africa 2004-2006.

| Unadjusted for Baseline | Adjusted for Baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Outcome | bICC | aEstimate (95% CI) | P value | aEstimate (95% CI) | P value |

| Unprotected vaginal intercourse in the past 3 months | 0.007 | 0.52 (0.31, 0.87) | 0.0126 | 0.51 (0.30, 0.85) | 0.0125 |

| Vaginal intercourse in the past 3 months | 0.005 | 0.62 (0.42, 0.94) | 0.0226 | 0.62 (0.42, 0.94) | 0.0225 |

| Multiple sexual partners in the past 3 months | 0.005 | 0.55 (0.31, 0.98) | 0.0435 | 0.50 (0.28, 0.89) | 0.0183 |

| Sexually in-experienced | 0.007 | 1.05 (0.76, 1.45) | 0.7746 | -- | -- |

| Anal intercourse in the past 3 months | 0.003 | 0.58 (0.33, 1.02) | 0.0588 | 0.60 (0.34, 1.05) | 0.0732 |

Estimate = OR (intervention versus health control).

ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient. ICCs were estimated by fitting a model using the generalized estimating equations approach and assuming an exchangeable working correlation structure with a logit link, unadjusted for baseline, controlling for clustering of learners within schools (n=18).

Secondary Outcomes

Averaged over follow-up, participants in the HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention were significantly less likely to report having vaginal intercourse (4.75% vs. 7.20%, p = 0.0225; d=0.29) and multiple sexual partners (1.83% vs. 3.19%, p = 0.0183; d=0.42) in the previous 3 months than were participants in the health-promotion control intervention, controlling for baseline prevalences.

At baseline 96.7% of participants reported never having vaginal intercourse. Boys were less likely than were girls to report sexual inexperience (93.5% versus 99.5%; p < 0.0001). Although the percentage who were sexually inexperienced decreased to 76.8% by the 12-month follow-up, the effect of the intervention on sexual inexperience was nonsignificant. In addition, although the participants in the HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention were less likely to report having heterosexual anal intercourse in the previous 3 months (1.98%) than were the participants in the health-promotion control intervention (3.34%), this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.0732; d=0.31). Few participants (0.38%) reported engaging in same-sex sexual behavior at baseline and only 3.97% ever reported such behavior by 12-month follow-up. The Intervention-Condition x Time interactions were nonsignificant, indicating that the effects of the intervention did not significantly differ among the 3 follow-up assessments.

Table 4, which presents the results of the meta-analyses, reveals that results at the school level were nearly identical to those at the individual level, though slightly more significant statistically. The test of heterogeneity of treatment effects among school pairs was not significant on any outcomes.

Table 4.

Meta-Analysis Estimates of Pooled Intervention Effects and Corresponding 95% Confidence Intervals of Predicted School Estimates from Fitted GEE Models.

| Meta-analysis of pooled intervention effects (unadjusted for baseline) |

Meta-analysis of pooled intervention effects (adjusted for baseline) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Outcome | aEstimate (95% CI) | P value | I2 (P value) | aEstimate (95% CI) | P value | I2 (P value) |

| Unprotected vaginal intercourse in the past 3 months |

0.52 (0.346, 0.770) | 0.001 | 0% (1.00) | 0.54 (0.360, 0.819) | 0.004 | 0% (1.00) |

| Vaginal intercourse in the past 3 months | 0.63 (0.468, 0.839) | 0.002 | 0% (1.00) | 0.65 (0.480, 0.875) | 0.005 | 0% (0.99) |

| Multiple sexual partners in the past 3 months |

0.55 (0.355, 0.862) | 0.009 | 0% (1.00) | 0.54 (0.339, 0.860) | 0.010 | |

| Sexually in-experienced | 1.06 (0.893, 1.254) | 0.511 | 0% (1.00) | -- | ||

| Anal intercourse in the past 3 months | 0.61 (0.397, 0.933) | 0.023 | 0% (1.00) | 0.55 (0.351, 0.867) | 0.010 | 0% (1.00) |

Estimate = OR (intervention versus health control). Predicted probabilities obtained from fitted GEE models, adjusted for clustering by school (column 2, Table 3). School summaries output to STATA Version 10 for computations of pooled intervention effects using “metan” command.

There were no adverse events.

COMMENT

The present results indicate that a theory-based, contextually appropriate HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention delivered in schools can be effective in shaping the sexual behavior of young adolescents before or at the beginning of their sexual lives. Averaged over the 3 follow-ups, the intervention reduced by approximately 50% the percentage of adolescents who reported unprotected vaginal intercourse compared with a health-promotion attention intervention. Moreover, the intervention’s efficacy did not differ significantly among the 3 follow-up assessment periods.

This study also revealed that averaged over the 3 follow-ups vaginal intercourse with multiple partners was reduced approximately 50% by the intervention compared with the control intervention. This is important because multiple partners, particularly concurrent partners, is believed to play a critical role in the spread of HIV.37-38 Interestingly, although the intervention produced a significant reduction in self-reported vaginal intercourse in the previous 3 months, it did not delay sexual debut. This contrasts with results of a study with adolescents in Namibia,9 in which the intervention delayed sexual debut, but did not reduce recent vaginal intercourse.

The rates of sexual activity in this sample of young adolescents were relatively low, which presents challenges in achieving adequate statistical power. Despite this, we obtained significant effects on important sexual behavior outcomes. That school-level analyses confirmed the primary individual-level analyses strengthens confidence in the findings. Some might reason that, because we applied Western theories to behavior change in sub-Saharan Africa, intervention effects would be weak. However, the effects were at least as strong as those in meta-analyses of interventions for adolescents in the US.39-42 The approach of integrating behavior-change theories with qualitative information from the population, then, may yield an efficacious contextually appropriate intervention.

Anal intercourse is considerably higher-risk for HIV transmission than is vaginal intercourse.43 Although the intervention effect on anal intercourse only approached statistical significance in the individual-level analysis, the school-level analysis revealed that the HIV/STD intervention produced a significant reduction in anal intercourse compared with the control intervention.

This study has several methodological strengths. It was conducted with young people in the context of a generalized HIV epidemic. The intervention was developed using both behavior-change theories and extensive formative research and delivered by well-trained cofacilitators who used manualized content. Participants were blind to intervention condition before enrollment, thus avoiding differential self-selection bias.44 Matched pairs of schools were randomized to conditions, an attention-control intervention was used, no schools withdrew from the study, and enrollment rates, intervention attendance, and follow-up retention were excellent, strengthening internal validity. Schools were randomly selected, strengthening generalizability to other schools in the area. In addition, the analyses appropriately adjusted for clustering among participants within schools assessed longitudinally.

A limitation of the study is the reliance on self-reports of behavior. Using incidence of STDs or HIV as an outcome was not feasible in our population with a 96.7% rate of sexual inexperience. Another limitation is that the results may not generalize to all South African adolescents. Few studies have been conducted with South Africans as young as our participants. Three studies that included adolescents comparable in age to our participants revealed rates of self-reported sexual inexperience greater than45-46 or similar to47 those we observed.

In conclusion, sexual transmission of HIV is a major risk faced by adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa, and interventions are needed urgently to reduce their risk. This study provides the first evidence that a theory-based, contextually appropriate intervention can reduce sexual risk behaviors, particularly unprotected vaginal intercourse, vaginal intercourse, and multiple partners, among young South African adolescents in the earliest stages of their sexual lives. Future research with more sexually experienced adolescents will have to explore whether such interventions can have an impact on condom use and STDs, including HIV.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the contributions of Sonya Coombs, Costa Gazi, MD, Lynnette Gueits, MS, Nicole Hewitt, PhD, Janet Hsu, BA, Xoliswa Mtose, MEd, Pretty Ndyebi, Mwezeni Nela, PhD, Robert Shell, PhD, Lulama Sidloyi, Gladys Thomas, MSW, MBA, Dalena White, MBA, and Tukufu Zuberi, PhD. The authors gratefully acknowledge the comments of Tom TenHave, PhD regarding the statistical analysis. This study was funded by a research grant from the National Institute of Mental Health 1 R01 MH065867. The funder of the study had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The corresponding author, Professor J. Jemmott, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Some of the data reported in this article were presented at the XVII International AIDS Conference, Mexico City, Mexico, August 7, 2008.

Footnotes

None of the authors have conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNAIDS . AIDS epidemic update. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and World Health Organization; Geneva: Dec, 2006b. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS . 2006 report on the global AIDS epidemic. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and World Health Organization; Geneva: 2006a. [Google Scholar]

- 3.SADOH . National HIV and syphilis antenatal sero-prevalence survey in South Africa 2005. National Department of Health; Pretoria: [Downloaded May 20, 2007]. 2006. at www.doh.gov.za/docs/reports-f.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorrington RE, Johnson LF, Bradshaw D, Daniel T. National and provincial indicators for 2006. Centre for Actuarial Research, South African Medical Research Council and Actuarial Society of South Africa; Cape Town: 2006. The demographic impact of HIV/AIDS in South Africa. www.commerce.uct.ac.za/Research_Units/CARE/RESEARCH/PAPERS/ASSA2003Indicators.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African American adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;279:1529–1536. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Braverman P, Fong GT. HIV/STI risk reduction interventions for African American and Latino adolescent girls at an adolescent medicine clinic: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(5):440–449. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, Lang DL, Davies SL, Hook EW, 3rd, Oh MK, Crosby RA, Hertzberg VS, Gordon AB, Hardin JW, Parker S, Robillard A. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(2):171–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirby D, Laris BA, Rolleri L. Impact of sex and HIV education programs on sexual behaviors of youth in developing and developed countries. Family Health International; Research Triangle Park: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul-Ebhohimhen VA, Poobalan A, van Teijlingen ER. [Accessed 12 March 2008];A systematic review of school-based sexual health interventions to prevent STI/HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 2008 8:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-4. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-4. at: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/8/4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klepp KI, Ndeki SS, Leshabari MT, Hannan PJ, Lyimo BA. AIDS education in Tanzania: promoting risk reduction among primary school children. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1931–1936. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.12.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanton BF, Li X, Kahihuata J, Fitzgerald AM, Neumbo S, Kanduuombe G, Ricardo I, et al. Increased protected sex and abstinence among Namibian youth following a HIV risk-reduction intervention: A randomized longitudinal study. AIDS. 1998;12:2473–2480. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199818000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross DA, Changalucha J, Obasi AI, Todd J, Plummer ML, Cleophas-Mazige B, Anemona A, Everett D, Weiss HA, Mabey DC, Grosskurth H, Hayes RJ. Biological and behavioural impact of an adolescent sexual health intervention in Tanzania: a community-randomized trial. AIDS. 2007;21(14):1943–1955. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ed3cf5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agha S, Van Rossem R. Impact of a school-based peer sexual health intervention on normative beliefs, risk perceptions, and sexual behavior of Zambian adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34:441–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fawole I, Asuzu M, Oduntan S, Brieger W. A school-based AIDS education programme for secondary school students in Nigeria: a review of effectiveness. Health Educ Res. 1999;14(5):675–683. doi: 10.1093/her/14.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy PS, James S, McCauley AP. Horiz Res Summary. Population Council; Washington, DC: 2003. Programming for HIV prevention in South African schools. [Google Scholar]

- 16.James S, Reddy PS, Ruiter RAC, Taylor M, Jinabhai CC, Van Empellen P, Van Den Borne B. The effects of a systematically developed photo-novella on knowledge, attitudes, communication and behavioural intentions with respect to sexually transmitted infections among secondary students in South Africa. Health Promot Int. 2005;20(2):157–165. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Statistics South Africa . Census 2001: Primary tables Eastern Cape: 1996 and 2001 compared. Statistics South Africa; Pretoria: [Accessed 14 August 2009]. 2004. at www.statssa.gov.za/census01/html/ECPrimary.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wainberg ML, Gonzalez MA, McKinnon K, Elkington KS, Pinto D, Mann CG, Mattos PE. Targeted ethnography as a critical step to inform cultural adaptations of HIV prevention interventions for adults with severe mental illness. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(2):296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jewkes R, Penn-Kekana L, Levin J, Ratsaka M, Schrieber M. Prevalence of emotional, physical and sexual abuse of women in three South African provinces. S Afr Med J. 2001;91:421–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jewkes R, Vundule C, Fidelia M, Jordaan E. Relationship dynamics and teenage pregnancy in South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:733–744. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Rand McNally; Chicago: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alberts M, Urdal P, Steyn K, Stenvold I, Tverdal A, Nel JH, Steyn NP. Prevalence of cardiovascular diseases and associated risk factors in a rural black population of South Africa. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev & Rehabil. 2005;12(4):347–354. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000174792.24188.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asfaw A. The effects of obesity on doctor-diagnosed chronic diseases in Africa: empirical results from Senegal and South Africa. J Public Health Policy. 2006;27:250–264. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz I. Kidney and kidney related chronic diseases in South Africa and chronic disease intervention program experiences. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2005;12(1):14–21. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kauth MR, St. Lawrence JS, Kelly JA. Reliability of retrospective assessments of sexual HIV risk behavior: a comparison of biweekly, three-month, and twelve-month self-reports. AIDS Educ Prev. 1991;3:207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sudman S, Bradburn NM. Response Effects in Surveys. Aldine; Chicago, Ill: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomized trials in health research. Oxford University Press Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalichman SC, Carey MP, Johnson BT. Prevention of sexually transmitted HIV infection: A meta-analytic review of the behavioral outcome literature. Ann Behav Med. 1996;18(1):6–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02903934. 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin DC, Diehr P, Perrin EB, et al. The effect of matching on the power of randomized community intervention studies. Stat Med. 1993;12:329–338. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780120315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diehr P, Martin DC, Koepsell T, et al. Breaking the matches in a paired t-test for community interventions when the number of pairs is small. Stat Med. 1995;14:1491–1504. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F, Chacon-Moscoso S. Effect-size indices for dichotomized outcomes in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods. 2003;8(4):448–467. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester, UK: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Halperin DT, Epstein H. Concurrent sexual partnerships help to explain Africa’s high HIV prevalence: implications for prevention. Lancet. 2004;364:4–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16606-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenberg MD, Gurvey JE, Adler N, Dunlop MB, Ellen JM. Concurrent sex partners and risk for sexually transmitted diseases among adolescents. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26(4):208–212. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199904000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Darbes L, Crepaz N, Lyles C, Kennedy G, Rutherford G. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk behaviors and incident sexually transmitted diseases in heterosexual African Americans. AIDS. 2008;22(10):1177–1194. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ff624e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mullen PD, Ramirez G, Strouse D, Hedges LV, Sogolow E. Meta-analysis of the effects of behavioral HIV prevention interventions on the sexual risk behavior of sexually experienced adolescents in controlled studies in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(Suppl 1):S94–S105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson BT, Carey MP, Marsh KL, Levin KD, Scott-Sheldon LA. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for the human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents, 1985-2000: a research synthesis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(4):381–388. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LA, Smoak ND, Lacroix JM, Anderson JR, Carey MP. Behavioral interventions for African Americans to reduce sexual risk of HIV: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(4):492–501. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a28121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mastro TD, de Vincenzi I. Probabilities of sexual HIV-1 transmission. AIDS. 1996;10(Suppl A):S75–S82. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199601001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, Morrison LA, Phetla G, Watts C, Busza J, Porter DH. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomized trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1973–1983. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richter LM. Studying adolescence. Science. 2006;312:1902–1905. doi: 10.1126/science.1127489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flisher AJ, Matthews C, Mukoma W, Lombard CJ. Secular trends in risk behaviour of Cape Town grade 8 students. S Afr Med J. 2006;96(9 Pt 2):982–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matthews C, Aaro LE, Flisher AJ, Mukoma W, Wubs AG, Schlaalma H. Predictors of early first sexual intercourse among adolescents in Cape Town, South Africa. Health Educ Res. 2008 Jan 17; doi: 10.1093/her/cym079. Advance Access published. doi:10.1093/her/cym079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]