Abstract

Objectives

The authors examined whether selected demographic and psychological factors would predict physical health dimensions in a sample of 53 cognitively high-functioning and ethnically diverse women (age 65-105).

Method

Predictors encompassed PTSD symptomatology and perceived stress (of a non-traumatic nature and beyond health status) in relation to all dimensions of physical health of the Medical Outcome Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey (MOS SF-36; J.E. Ware & C.D. Sherbourne, 1992). Age and income, well-known correlates of health in the target population, were included as potential predictors. The authors first tested the relationship between potential predictors and health dimensions via a canonical correlation analysis, and then employed full multiple regression analyses to simultaneously test the predictors in each health dimension model.

Results

Perceived stress was a significant predictor of lower levels of general health (GH), but not of physical role limitations (PRL) or physical functioning (PF). Conversely, PTSD symptomatology predicted more limitations in role fulfillment (and, to a lesser extent, impaired physical functioning), but not lower levels of GH. As expected, age and income were predictive of some physical health dimensions. The hypothesized predictors failed to account for a significant portion of variance in pain scores.

Conclusion

PTSD symptomatology and perceived stress might influence older women’s physical health dimensions differentially; additional research on larger samples is needed to corroborate these findings.

Keywords: physical functioning, posttraumatic stress disorder, distress, ethnic minorities

Introduction

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptomatology and stress of a non-traumatic nature from a variety of sources can have an adverse impact on physical well-being, according to several conceptualizations of the deleterious effects of stress on health. Lazarus, DeLongis, Folkman, and Gruen (1985) stated that there would be no environmental stressors without individuals who are vulnerable to them, with people’s internal and external resources determining stress outcomes such as physical health. It is critical to target women in studies on this topic because, according to prior research findings (e.g., Charles & Almeida, 2007), they tend to perceive stressors as more severe than men, with over 50% of women in the U.S. being exposed to at least one traumatic experience over the course of their life (Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, & Hughes, 1995). In older age, the 6-month prevalence of subtreshold PTSD, not meeting the full diagnostic criteria for PTSD of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TR (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000), is a high 13.1% (van Zelst, de Beurs, Beekman, Deeg, & van Dyck, 2003). Subthreshold PTSD often goes untreated in older populations, both as a result of PTSD’s episodic course (Averill & Beck, 2000; Hyer, Summers, Braswell, & Boyd, 1995) and underreporting (Tyra, 1993). Yet, like full PTSD, it is associated with decreased well-being, impaired functioning, and higher utilization of health care services for medically unexplained somatic symptoms (van Zelst, de Beurs, Beekman, van Dyck, & Deeg, 2006).

Regarding PTSD symptomatology in relation to health, empirical evidence links a history of PTSD to both higher somatization symptomatology (e.g., Andreski, Chilcoat, & Breslau, 1998) and physical impairment among ethnically diverse women (e.g., Amaya-Jackson et al., 1999). A significant relationship also exists between chronic non-traumatic stress and increased likelihood of developing PTSD after exposure to trauma (e.g., Kubiak, 2005). A close look at the literature on PTSD and health reveals that there is a disproportionately higher amount of information available on men than women. This is perhaps due, at least partially, to gender differences in combat experience and related use of Veteran’s Administration facilities. Nonetheless, empirically evidence on women who underwent potentially traumatic experiences illustrates the negative impact of PTSD on physical and mental health outcomes in populations including female veterans (e.g., Zinzow, Grubaugh, Monnier, Suffoletta-Maierie, & Frueh, 2007), women exposed to unrelenting stalking (e.g., Mechanic, 2004), and those experiencing intimate partner violence (e.g., Dutton et al., 2006; Pico-Alfonso et al., 2006). In regard to older women in particular, those with a history of emotional abuse report more digestive problems, chronic pain, heart problems, and high blood pressure (among other health conditions) than older women without such a history (Fisher & Regan, 2006). Yet, the literature contains very limited information on specific health manifestations of traumatic stress symptomatology in non-clinical samples of ethnically diverse older women.

As to stress and physical health, researchers have linked daily stress to the occurrence of health problems such as sore throat, flu, backaches, and headaches (e.g., DeLongis, Folkman, & Lazarus, 1988). Stress can precipitate immune functioning suppression and related illnesses, but can also impact the body’s ability to regulate immune functioning by inducing autoimmune disease (Koenig & Cohen, 2002). Particularly relevant to this discussion is the concept of allostatic load, i.e., the cumulative physiological burden put on the body through attempts to adapt to the demands of life (Seeman, McEwen, Rowe, & Singer, 2001). In the long run, when challenges become chronic or the allostatic system remains turned on unnecessarily, adaptive physiological reactions to stressors cause body changes often leading to illness (McEwen, 2000). The cumulative weight of coping with negative life events while possessing inadequate resources typically increases allostatic load, a situation most common among low-income individuals (McEwen & Seeman, 2006) and potentially applicable to this study’s target population. Higher allostatic load predicts an enhanced risk for lower levels of physical functioning and higher incidence of cardiovascular problems (e.g., Seeman, Singer, Rowe, Horwitz, & McEwen, 1997) among older adults. Unlike research on PTSD, there is more empirical evidence on women than men regarding the negative impact of specific non-traumatic stressors on health. This has been demonstrated for older women in caregiver (not necessarily spousal) roles that often affect their physical functioning adversely (e.g., Pinquart & Sorenson, 2003). The same frequently happens upon experiencing stressors such as the death of one’s spouse (e.g., Lee & Carr, 2007), especially among older women who viewed being married as their most valuable role (Krause, 2004). Concerning the scarce body of research on stress and health in non-Caucasian populations, Green, Baker, & Smith (2003) discovered that higher stress levels are related to chronic pain particularly among women of African-American descent.

Upon studying the stress-health link in older adults, researchers have acknowledged a variety of potentially stressful situations, including challenging economic circumstances (Pearlin & Skaff, 1998). People with a non-privileged status often have the highest chances of being exposed to stressors (Pearlin, Schieman, Fazio, & Meersnam, 2005). Advanced old age and low socio-economic status (SES) are known predictors of unfavorable health outcomes (e.g., Shavers, 2007), thus these two factors must be considered in studies on older women’s physical health. The development of a disability occurs much more frequently among older adults without private health insurance coverage (Landerman et al., 1998), and poor self-rated health is significantly related to lack of health insurance, most common among low-income older individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds (Fillenbaum & Hanlon, 2006). Moreover, empirical evidence suggests that women in general, and ethnic minorities in particular, are especially susceptible to poorer health and earlier mortality related to low SES (e.g., Ghaed & Gallo, 2007; Jemal et al., 2008; Shavers, 2007). The above information underscores the importance of studying older women’s socio-demographic health predictors.

Considerations of non-traumatic stress are generally absent in conjunction with the assessment of PTSD symptomatology in community-based geriatric samples. Literature is noticeably lacking on the simultaneous contribution of older women’s symptoms of PTSD, non-traumatic stress, and key demographics to physical health. Also, with some exceptions (e.g., Son et al., 2007), many researchers have traditionally examined the relationship between health and stress utilizing one-dimensional health measures, thereby possibly missing clinically-relevant information on distinct facets of health. In the present study, we used selected demographics and self-reported stress reactions as potential predictors of older women’s distinct health dimensions. The theoretical framework of this investigation is Engel's (1977; 1980) classic biopsychosocial model of medicine, which views health as affected by a variety of factors. In line with this conceptualization, we hypothesized that, together with more advanced age and lower income, higher PTSD symptomatology and perceived stress (of a non-traumatic nature and beyond health status) would predict lower scores on four dimensions of physical health.

Method

Participants

We secured a sample of 53 community-dwelling women, age 65-105, who resided in Los Angeles County, a good location for gathering an ethnically diverse sample. Respondents’ characteristics are illustrated in Table 1; their scores varied across psychological, physical, and demographic factors. The latter included age, income, ethnicity, marital status and education. Ethnic minorities comprised almost half of the sample (47.2%).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics on the Sample (N = 53)

| Variable | Mean | SD | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (65-105) | 74.8 | 8.70 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| African-American | 11.3 | ||

| Asian-American | 1.9 | ||

| European-American | 52.8 | ||

| Mexican-American | 22.6 | ||

| Other Hispanic-American | 5.7 | ||

| Armenian | 5.7 | ||

| Stated Income | |||

| Less than $20,000 | 39.6 | ||

| $20,000 - $39,999 | 24.5 | ||

| $40,000+ | 26.4 | ||

| Refused to Answer | 9.4 | ||

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 3.8 | ||

| Divorced | 15.1 | ||

| Married | 32.1 | ||

| Widowed | 49.1 | ||

| Education | |||

| Less than High School | 24.5 | ||

| Graduated from High School | 34.0 | ||

| Completed Trade School | 3.8 | ||

| Some College | 18.9 | ||

| Graduated from College (B.A./B.S.) | 7.5 | ||

| Post-Graduate Education | 9.5 | ||

| Refused to Answer | 1.9 | ||

| Non-Traumatic Stress Total | 13.13 | 9.77 | |

| PTSD Symptomatology Total | 3.36 | 2.97 | |

| MOS SF-36 Physical Functioning Total | 55.82 | 29.15 | |

| MOS SF-36 Role-Physical Total | 59.91 | 42.56 | |

| MOS SF-36 General Health Total | 57.32 | 23.50 | |

| MOS SF-36 Absence of Bodily Pain Total | 61.66 | 23.07 |

Study eligibility was limited to women who were age 65 or older and able to speak and comprehend English. Respondents were excluded on the basis of: (1) significant cognitive impairment, assessed via using a screener for dementia, as detailed below; (2) residence in an institutionalized setting; and (3) inability to provide informed consent. Setting the above exclusion criteria allowed us to minimize the occurrence of approaching older women with severe cognitive difficulties (often residing in geriatric institutions).

Procedures

Sample recruitment strategies included utilization of connections of interviewers/research assistants within their respective ethnic communities and snowball sampling (implemented by asking participants to refer other older women to the study). Research assistants were trained in interviewing and assessment skills, as well as cultural competence and active listening. The study was conducted at respondents’ homes or at locations near their places of residence (e.g., senior centers and libraries). Participants were first assigned a code number placed on their assessment packet (no names were recorded for confidentiality reasons), then screened using a measure to rule out dementia. Eligible respondents were individually administered the assessment battery described next. To minimize their fatigue and keep research procedures as homogeneous as possible, we instructed interviewers to: (1) hand write all answers; (2) take a short break in the middle of the assessment session; and then (3) administer the remainder of the battery.

Instruments

The assessment packet included five measures: (1) the Mini-Cog; (2) a demographic list; (3) the Brief Posttraumatic Stress Screening Scale; (4) the Older Women’s Perceived Stress beyond Health Status Scale; and (5) the Medical Outcome Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey.

The Mini-Cog

First, each potential participant was screened for dementia via administration of the Mini-Cog (Borson, Scanlan, Brush, Vitaliano, & Dokmak, 2000). This tool includes an uncued three-item recall test (with one point assigned per word recalled) and a clock drawing test, scored as 0 if “abnormal” and 2 if “normal”. A clock is considered normal when all numbers are in the right direction and order (as well as being spaced evenly within the circle), with the two clock hands correctly pointing to 10 past 11. A total score of 3 or higher indicates absence of major cognitive impairment. Borson, Scanlan, Chen, and Ganguli (2003) successfully validated this measure on a sample of older adults from diverse ethnic backgrounds. In the present study, the Mini-Cog was used only for screening purposes, not in the data analyses. Respondents with scores ranging from 3 to 5 continued the assessment session, i.e., all the women originally approached.

Demographic List

This list, developed by Lagana`, is a 10-item tool containing questions on demographic variables such as age, ethnicity, marital status, education, and stated income.

The Brief Posttraumatic Stress Screening Scale

The Brief Posttraumatic Stress Screening Scale (BPSSS; Lagana` & Schuitevoerder, 2009) is the new abbreviated version of the 20-item Distressing Event Questionnaire (DEQ; Kubany, Leisen, Kaplan, & Kelly, 2000) that assesses PTSD symptomatology based on the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). This five-item tool uses two items to measure criterion B: re-experiencing, two to assess criterion C: avoidance/numbing, and one to measure criterion D: increased arousal. The BPSSS was designed to quickly screen for PTSD symptomatology in a fast-paced medical setting. Scores on this measure do not provide definite evidence for the formulation of a PTSD diagnosis, thus the total scores (ranging from 0 to 11) obtained in the present study cannot be clinically interpreted beyond the fact that higher scores indicate higher levels of PTSD symptomatology. The name “Brief Posttraumatic Stress Screening Scale” reflects the focus of this measure on quantifying posttraumatic stress reactions (within the past 30 days) related to an unspecified yet worse/most distressing experience ever had. Respondents were asked to refer to such an experience when answering questions on a Likert-type scale. Scores on each of the five symptom-related items range from 0, i.e., absent or did not occur, to 4, i.e., present to an extreme or severe degree. Kubany, the first author of the DEQ, created the BPSSS (as further detailed in Lagana` & Schuitevoerder, 2009) at the Honolulu National Center for PTSD by selecting the five DEQ items that had the highest correlational values (ranging from .75 to .91) with the total DEQ scores obtained in two PTSD studies (described in Kubany et al., 2000). In the aforementioned research on a non-clinical sample of ethnically diverse older women (N = 94) by Lagana` & Schuitevoerder, this short version of the DEQ demonstrated high intra-item reliability (Cronbach’s α = .86). In the same study, the concurrent validity of the BPSSS with depression (assessed via the SelfCARE D, a geriatric depression scale; Abas, Hotopf, & Prince, 2002) was adequate (r = .50), considering that the two scales measure somewhat overlapping yet distinct psychiatric constructs.

The Older Women’s Perceived Stress beyond Health Status Scale

This nine-item tool (Prilutsky, 2006) quantifies stress caused by nine potential stressors, including (but not limited to) the emotional strain related to spousal loss, geographic isolation from loved ones, financial strain, and caregiving stress (without inquiring about the number of people cared for or their age cohort). It was developed specifically for use with ethnically diverse older women. The definition of stress as it applies to this measure is based on a cognitive/phenomenological framework, according to which an individual must perceive a demand or stressor and concurrently experience some degree of tension as a response to it (Hennon & Brubaker, 1994). In line with such a conceptualization, this short tool quantifies the recognition and perception of a variety of events as personally stressful. Respondents rated stress levels on a Likert-type scale, with scores ranging from 0, i.e., not at all stressful, to 5, i.e., extremely stressful. The option “N/A” was available in case stressors were not applicable. This measure has shown strong discriminant validity (r = .11; Prilutsky, 2006) relative to depressive symptomatology quantified by the SelfCARE D (Abas, Hotopf, & Prince, 2002). In Lagana` and Prilutsky‘s (2009) research in progress on 246 older women (mainly from non-European-American backgrounds), the tool in question demonstrated adequate intra-item reliability for a tool assessing reactions to a heterogeneous group of stressors from multiple domains (Cronbach’s α = .70). Given that this instrument, unlike many of its kind, does not address stress related to experiencing health problems, its use is particularly appropriate when attempting to predict dimensions of physical health.

The Medical Outcome Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey

The MOS SF-36 (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992) contains eight scales, four on physical health and four on mental health; its questions have a 5-point response format (from strongly disagree to strongly agree), with higher scores indicating higher physical well-being. In the present study, we used all four scales on physical health to operationalize the outcome variables, i.e., general health (GH); physical functioning (PF, i.e., ability to engage in activities of daily living); physical role limitations (PRL, i.e., limitations in role that respondents were previously accustomed to filling); and bodily pain (BP, i.e., magnitude of pain and pain interference in accomplishing daily activities). This instrument is very reliable when administered to community-dwelling older adults, with high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α > .80 for all MOS SF-36 scales; Lyons, Perry, & Littlepage, 1994). We utilized the MOS SF-36 software to first convert the raw data into standardized scores, and then convert such standardized scores into T scores with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. In the manual of the MOS SF-36, Ware, Kosinski, and Keller (1994) recommended that researchers do not overlook this normative standardization step, otherwise the reliability and validity of the MOS SF-36 scales could be compromised.

Analytic Strategy

We computed descriptive statistics for all variables and performed a canonical correlation for two sets of variables, i.e., the hypothesized predictors and the four health dimensions. The values in Table 1 were computed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; not all total percentages add up to exactly 100, due to rounding. We planned to run a series of multiple regression analyses in the event that the canonical analysis confirmed the feasibility of their implementation. Regression models were specified to take into account the simultaneous contribution of the four potential predictors to variance in each of the four health dimensions. Concerning missing data, no individual failed to respond to any of the MOS SF-36, PTSD symptomatology, and stress questions. This was also the case for most demographics, with the exception of income, as five participants declined to provide information on this variable. Thus, the sample size for the canonical and multiple regression analyses dropped from 53 to 48.

Results

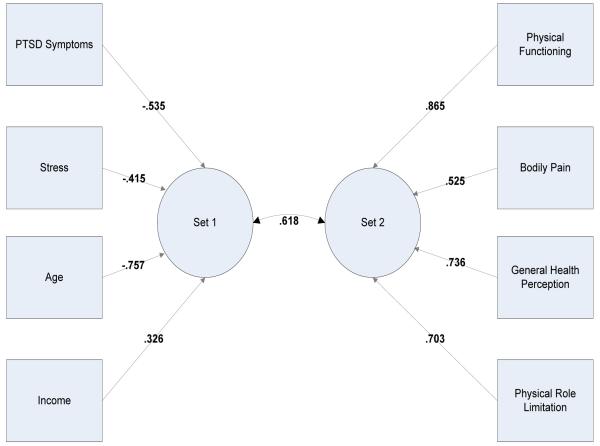

We first tested whether there was a significant relationship between predictors and the health dimensions, namely physical functioning (PF); bodily pain (BP); general health (GH); and physical role limitations (PRL), while controlling for an overall type 1 error rate (α). The first canonical correlation showed a significant relationship between the two sets of variables, χ2 (16) = 33.187, p = .007. The canonical loadings are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Canonical Loadings for Two Variable Sets for Model 1

The model tested accounted for approximately 38% of the variability between the two sets of variables (the remaining canonical correlation coefficients extracted were not significantly different from zero). This finding indicated that a significant and sizeable relationship (especially in view of the small sample size) existed between predictors and health outcomes. Thus, we performed four full multiple regression analyses as planned. The size of the final sample is statistically adequate because the corresponding N/k ratio is over 10 (48/4 = 12), hence the regression coefficient estimates can be considered stable, according to Tabachnick and Fidell (2007). Following those authors’ guidelines, we added income to the regression models as a categorical variable.

Table 2 displays the F and R2 values, as well as the standardized and nonstandardized regression coefficients regarding the analyses summarized below. Physical role limitation was analyzed in the first full multiple regression, achieving overall significance, p = .016. Both BPSSS scores, t(4) = −2.663, p = .011, and age, t(4) = −2.015, p = .05, were significant predictors of physical role limitation. Income and non-traumatic stress did not PRL. The second analysis, on physical functioning, was statistically significant overall, with both age, t(4) = −3.586, p = .001, and income, t(4) = 2.100, p = .042, predicting physical functioning. PTSD symptomatology, although not a significant predictor in this model, showed a trend in the same direction of age and income, t(4) = −1.746, p = .088. Non-traumatic stress was not a significant predictor. The third analysis, conducted to predict GH, obtained overall statistical significance: non-traumatic stress was a significant predictor, t(4) = −2.199, p = .033, and age showed a trend towards predicting GH, t(4) = −1.781, p = .082. Income and PTSD symptomatology did not achieve significance. Contrary to expectations, the fourth data analysis failed to produce significant results in regard to bodily pain, thus its findings are not displayed.

Table 2.

Full Multiple Regression Analyses (N = 48)

| Predictor Variables | Dependent Variable (Physical Role Limitation) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| B | SE B | β | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age | −1.497 | .743 | −.269* |

| Income | −1.081 | 6.936 | −.021 |

| Mental Health Variables | |||

| PTSD Symptomatology | −5.527 | 2.076 | −.374* |

| Non-Traumatic Stress | −.409 | .651 | −.089 |

| Predictor Variables | Dependent Variable (Physical Functioning) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| B | SE B | β | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age | −1.716 | .478 | −.454*** |

| Income | 9.376 | 4.465 | .269* |

| Mental Health Variables | |||

| PTSD Symptomatology | −2.332 | 1.336 | −.232+ |

| Non-Traumatic Stress | .160 | .419 | .051 |

| Predictor Variables | Dependent Variable (General Health) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Variable | B | SE B | β |

| Demographics | |||

| Age | −.686 | .385 | −.233+ |

| Income | 5.048 | 3.595 | .186 |

| Stress Variables | |||

| PTSD Symptomatology | −1.321 | 1.076 | −.169 |

| Non-Traumatic Stress | −.742 | .337 | −.306* |

Note: R2= .242; F(4,43) = 3.427*;

p < .05

Note:R2= .319; F(4,43) = 5.032**;

p < .05

** p < .01

p < .001

p < .10

Note: R2=.272; F(4,43) = 4.011**;

p < .05

** p < .01

p < .10

Discussion

We investigated the simultaneous contribution of selected factors (i.e., non-traumatic stress, PTSD symptomatology, age, and income) to four health dimensions in a sample of older women split almost equally between European-Americans and ethnic minorities. Data analyses produced interesting findings with regard to how non-traumatic stress and PTSD symptomatology can uniquely manifest in relation to distinct aspects of physical health. Certainly, these results should be interpreted with caution, given the pilot nature of the present investigation.

Higher levels of non-traumatic stress were predictive of lower GH. This result is consistent with existing empirical evidence on the stress-health link in non-European-American younger populations (e.g., Ravenell, Johnson, & Whitaker, 2006). However, in spite of worse health perceptions, women with higher non-traumatic stress levels did not report significant limitations in physical role or worsened physical functioning, maintaining normal levels of functioning and adequate role fulfillment. This is consistent with life-span conceptualizations of high reserve capacities in older age (e.g., Staudinger, Marsiske, & Baltes, 1993). It also corroborates prior empirical evidence demonstrating that older women can often maintain normal functioning after experiencing major negative life events (e.g., Rossi, Bisconti, & Bergeman, 2007), although they frequently report health deterioration when facing stressors related to highly valued roles (e.g., Krause, 2004). Opposite to the above finding, women with higher PTSD symptomatology experienced more limitations in role fulfillment. There was a trend in the same direction regarding worse physical functioning, in line with Amaya-Jackson et al.’s (1999) results on a non-geriatric sample of ethnically diverse women. To offer one of many potential interpretations of the difference between the findings on perceived stress and PTSD symptomatology, perhaps respondents with higher perceived stress were experiencing acute stressors (reflected in their higher stress scores). Such circumstances could have affected the functioning of their immune system negatively, resulting in an acute illness (not assessed in this study) and concomitant lower health reports. Conversely, it is possible that the pathological nature of PTSD symptomatology impaired functioning at a more fundamental level, thereby decreasing ability for role fulfillment (and, to a lesser degree, for adequate physical functioning).

More advanced age was a risk factor for physical role limitations and physical functioning (with a trend in the same direction regarding GH), indicating an age-related decline in older women’s ability to perform activities and fully engage in roles previously filled. This corroborates existing empirical evidence demonstrating that higher age is related to worse health reports and limited ability to fill roles (e.g., Gama et al., 2000; Hoeymans, Feskens, Kromhout, & van den Bos, 1997; Rohrer, Merry, Rohland, Rasmussen, & Wilshusen, 2008). It should be kept in mind that age, income, and physical health are closely interrelated in the literature, with economic status often decreasing with more advanced age and common concurrent declines in physical health. This might be particularly relevant to our target population, given that at least 3.3 million older Americans have income levels below the federal poverty line (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006), and nearly 70% of poor older adults are women (Gonyea & Hooyman, 2005). In the present study, higher income predicted better physical functioning, corroborating prior research findings (e.g., Shavers, 2007). Contrary to what was expected, the four hypothesized risk factors were not significantly related to bodily pain. Research on the stress-pain link has produced mixed findings and its discussion is beyond the scope of the present investigation. Interested readers are referred to work by researchers such as Zautra, Hamilton, Potter, and Smith (1999), Green et al. (2003), Skinner, Zautra, and Reich (2004), as well as Edwards, Moric, Husfeldt, Buvanendran, and Ivankovich (2008) for more information on this topic.

Although our findings on stress and PTSD symptomatology in relation to health dimensions are intriguing, this study is preliminary in nature, hence it has several limitations. Among them is the very modest sample size, which allowed the use of only a limited number of predictors. This precluded investigation of other potential risk and protective factors (as well as moderators and mediators) within the stress-health relationship, such as information on patient-health provider relationship, specific caregiving duties, and medication use, to name a few. We did not use a tool to assess history of traumatic events due to the risk of causing undue stress among participants. There is an ethical issue to bear in mind when probing into delicate traumatic material without an unquestionable reason to do so, which we did not have in this preliminary study. The PTSD symptomatology tool quantified psychopathology that was considerable enough to obtain significant health-related results on this variable, given the non-psychiatric nature of the sample. Another limitation of this correlational study is that the results obtained do not imply causation. Limitations in physical and role functioning, as well as specific medical conditions (not assessed herein), can precipitate higher stress levels. Indeed, health variables can influence stress reactions (e.g., Taylor et al., 2008) and anxiety symptoms typically manifest as a result of older adults’ physical illnesses such as pulmonary embolus or angina (e.g., Hocking & Koenig, 1995).

There are several ways in which the present findings could inform future research and related hypothesis testing. For instance, prospective studies on whether symptoms of PTSD and non-traumatic stress affect various dimensions of older women’s physical health differentially could test which particular stressors precipitate worse health declines within separate health dimensions. This research could utilize well-established (although usually much lengthier) PTSD and stress tools, together with a traumatic event measure if at all feasible. Researchers should use bigger samples and recruit ethnic minorities in numbers large enough to conduct ethnic comparisons and test whether maintenance of high physical functioning in spite of stressful circumstances occurs across ethnicities. Moreover, our four predictors could be included in causal models to be validated in longitudinal research on traumatized as well as non-traumatized populations. Such studies could clarify, for instance, whether non-traumatic stress is more predictive of acute physical problems, while PTSD symptomatology predicts stable, mainly role-related impairments over time. It would be useful to add information on potentially relevant medical factors to these models, such as immune functioning and physical illness (from a reliable source such as respondents’ health providers, if possible). This could ideally be coupled with physiological measures of health and a measure probing into cultural factors related to health perceptions. Investigators could then verify self-reports, relate respondents’ health perceptions to formally diagnosed conditions, and examine whether cultural variables play a role in self-reports of different health dimensions. Health insurance coverage should be considered as another potential predictor (or control variable), because worse health is very common in low-income, ethnically diverse older adults who often do not have health insurance (Fillenbaum & Hanlon, 2006).

In conclusion, the present findings on PTSD symptomatology and perceived stress suggest that it might be salient to use multi-dimensional measures of health when investigating the stress-health link among ethnically diverse older women, to avoid missing clinically-relevant information. This study should be replicated with larger samples before attempting to generalize the findings obtained to our target population. Nonetheless, its results have potential for being applicable to health care settings and offer groundwork information alerting researchers and clinicians to the importance of both non-traumatic and traumatic stress in relation to various facets of older women’s physical health.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by NIH MBRS SCORE grant # 2 S06 GM048680-12A1 and NIH NIGMS MARC grant # 2T34 GM00835, Luciana Lagana`, Principal Investigator. We thank Dr. Kubany for offering us to use his PTSD screen in this research, as well as Dr. Andrew Ainsworth, this study’s statistical consultant, for his careful input.

Contributor Information

Luciana Lagana`, Department of Psychology, California State University Northridge, Northridge, U.S.A..

Stacy L. Reger, Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Nevada Las Vegas, Las Vegas, U.S.A.

References

- Abas M, Hotopf M, Prince M. Depression and mortality in a high-risk population: 11-year follow-up of the Medical Research Council Elderly Hypertension Trail. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;181(2):123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaya-Jackson L, Davidson JR, Hughes DC, Swartz M, Reynolds V, George LK, Blazer DG. Functional impairment and utilization of services associated with posttraumatic stress in the community. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1999;12(4):709–724. doi: 10.1023/A:1024781504756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Andreski P, Chilcoat H, Breslau N. Post-traumatic stress disorder and somatization symptoms: A prospective study. Psychiatry Research. 1998;79(2):131–138. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averill P, Beck G. Posttraumatic stress disorder in older adults: A conceptual review. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2000;14(2):133–156. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(99)00045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borson S, Scanlan JM, Brush M, Vitaliano P, Dokmak A. The Mini-Cog: A cognitive 'vital signs' measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2000;15(11):1021–1027. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200011)15:11<1021::aid-gps234>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: Validation in a population-based sample. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(10):1451–1454. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles S, Almeida D. Genetic and environmental effects on daily life stressors: More evidence for greater variation in later life. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22(2):331–340. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLongis A, Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The impact of daily stress on health and mood: Psychological and social resources as mediators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(3):486–495. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.3.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Green BL, Kaltman SI, Roesch DM, Zeffiro TA, Krause ED. Intimate partner violence, PTSD, and adverse health outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21(7):955–968. doi: 10.1177/0886260506289178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RR, Moric M, Husfeldt B, Buvanendran A, Ivankovich O. Ethnic similarities and differences in the chronic pain experience: A comparison of African American, Hispanic, and White patients. Pain Medicine. 2008;6(1):88–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel GL. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1980;137(5):535–544. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.5.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum GG, Hanlon JT. Racial and ethnic disparities in medication use among older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy. 2006;4(2):93–95. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, Regan SL. The extent and frequency of abuse in the lives of older women and their relationship with health outcomes. The Gerontologist. 2006;46(2):200–209. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama E, Damian J, Perez de Molino J, Lopez M, Lopez-Perez M, Gavira-Iglesias F. Association of individual activities of daily living with self-rated health in older people. Age and Ageing. 2000;29(16):267–270. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaed SG, Gallo LC. Subjective social status, objective socioeconomic status, and cardiovascular risk in women. Health Psychology. 2007;26(6):668–674. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonyea JG, Hooyman NR. Reducing poverty among older women: Social security reform and gender equity. Families in Society. 2005;86(3):338–346. [Google Scholar]

- Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, Kaloukalani DA, Lasch KE, Myers C, Tait RC, Toll KH, Vallerand AH. The unequal burden of pain: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Medicine. 2003;4(3):277–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green C, Baker T, Smith E. The effect of race in older adults presenting for chronic pain management: A comparative study of black and white Americans. The Journal of Pain. 2003;4(2):82–90. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2003.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennon CB, Brubaker TH. Divorce and health care in later life. In: Schwartz LL, editor. Mid-life divorce counseling. American Counseling Association; Alexandria, VA: 1994. pp. 39–63. The family psychology and counseling series. [Google Scholar]

- Hocking LB, Koenig HG. Anxiety in medically ill older patients: A review and update. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1995;25(3):221–238. doi: 10.2190/XRGV-FD1A-VWP5-RE9Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeymans N, Feskens EJM, Kromhout D, van den Bos GAM. Ageing and the relationship between functional status and self-rated health in elderly men. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;45(10):1527–1536. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyer L, Summers M, Braswell L, Boyd S. Posttraumatic stress disorder: Silent problem among older combat veterans. Psychotherapy. 1995;32:348–364. [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Thun MJ, Ward EE, Henley SJ, Cokkinides V, Murray T. Mortality from leading causes by education and race in the United States, 2001. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Cohen HJ. Psychological stress and autoimmune disease. In: Koenig HG, Harvey HJ, editors. The Link between Religion and Health: Psychoneuroimmunology and the Faith Factor. Oxford University; New York: 2002. pp. 174–196. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Stressors arising in highly valued roles, meaning in life, and the physical health status of older adults. Journal of Gerontology. 2004;59(5):S287–S297. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.5.s287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Leisen MB, Kaplan AS, Kelly MP. Validation of a brief measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The Distressing Event Questionnaire (DEQ) Psychological Assessment. 2000;12(2):197–209. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubiak SP. Trauma and cumulative adversity in women of a disadvantaged social location. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75(4):451–465. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagana` L, Prilutsky R. The Older Women’s Perceived Stress beyond Health Status Scale: A validation study. 2009. Manuscript in progress.

- Lagana` L, Schuitevoerder S. Pilot testing a new short screen for the assessment of older women’s PTSD symptomatology. Educational Gerontology. 2009;35(8):732–751. doi: 10.1080/03601270802708442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landerman LR, Fillenbaum GG, Pieper CF, Maddox GL, Gold DT, Guralnik JM. Private health insurance coverage and disability among older Americans. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1998;53(5):258–266. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.5.s258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, DeLongis A, Folkman S, Gruen R. Stress and adaptational outcomes: The problem of confounded measures. American Psychologist. 1985;40(7):770–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Carr D. Does the context of spousal loss affect the physical functioning of older widowed persons? A longitudinal analysis. Research on Aging. 2007;29(5):457–487. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons RA, Perry HM, III, Littlepage BNC. Evidence for the validity of the Short-form 36 Questionnaire (SF-36) in an elderly population. Age and Ageing. 1994;23(3):182–184. doi: 10.1093/ageing/23.3.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Allostasis, allostatic load, and the aging nervous system: Role of excitatory amino acids and excitotoxicity. Neurochemical Research. 2000;25;(9/10):1219–1231. doi: 10.1023/a:1007687911139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Seeman T. Protective and damaging effects of mediators of stress: Elaborating and testing the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;896:30–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic MB. Beyond PTSD: Mental health consequences of violence against women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19(11):1283–1289. doi: 10.1177/0886260504270690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, Meersnam SC. Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46(2):205–219. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Skaff MM. Perspectives on the family and stress in late life. The Plenum series in adult developing and aging. In: Lomranz J, editor. Handbook of Aging and Mental Health: An Integrative Approach. Plenum Press; New York: 1998. pp. 323–340. [Google Scholar]

- Pico-Alfonso MA, Garcia-Linares MI, Celda-Vavarro N, Blasco-Ros C, Echeburúa E, Martinez M. The impact of physical, psychological, and sexual intimate male partner violence on women’s mental health: Depressive symptoms, Posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and suicide. Journal of Women’s Health. 2006;15(5):599–611. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18(2):250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prilutsky R. Preliminary Reliability and Validity Study on a New Scale Measuring Perceived Stress beyond Health Status among Older Women. 2006. Unpublished master’s thesis, California State University Northridge, Northridge, California.

- Ravenell J, Johnson W, Whitaker E. African American men’s perceptions of health: A focus group study. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006;98(4):544–560. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer J, Merry S, Rohland B, Rasmussen N, Wilshusen L. Physical limitations and self-rated overall health in family medicine patients. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2008;22(1):38–44. doi: 10.1177/0269215507079095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi NE, Bisconti TL, Bergeman CS. The role of dispositional resilience in regaining life satisfaction after the death of a spouse. Death Studies. 2007;31(10):863–883. doi: 10.1080/07481180701603246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, McEwen BS, Rowe JW, Singer BH. Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98(8):4770–4775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081072698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Singer BH, Rowe JW, Horwitz RI, McEwen BS. Price of adaptation—Allostatic load and its health consequences. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157(19):2259–2268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL. Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2007;99(9):1013–1020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner MA, Zautra AJ, Reich JW. Financial stress predictors and the emotional and physical health of chronic pain patients. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2004;28(5):695–713. [Google Scholar]

- Son J, Erno A, Shea DG, Femia EE, Zarit SH, Parris Stephens MA. The caregiver stress process and health outcomes. Journal of Aging and Health. 2007;19(6):871–887. doi: 10.1177/0898264307308568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger UM, Marsiske M, Baltes PB. Resilience and levels of reserve capacity in later adulthood: Perspectives from life-span theory. Development & Psychopathology. 1993;5:541–566. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5th Allyn & Bacon; Boston, MA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MK, Markham AE, Reis JP, Padilla GA, Potterat EG, Drummond SPA, Mujica-Parodi LR. Physical fitness influences stress reactions to extreme military training. Military Medicine. 2008;173(8):738–742. doi: 10.7205/milmed.173.8.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyra PA. Older women: Victims of rape. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 1993;19(5):7–12. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19930501-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States. 2006 2003. Retrieved April 26, 2008, http://www.census.gov/prod/2007pubs/p60-233.pdf.

- van Zelst WH, de Beurs E, Beekman ATF, van Dyck R, Deeg DJH. Well-being, physical functioning, and use of health services in the elderly with PTSD and subthreshold PTSD. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;21(2):180–188. doi: 10.1002/gps.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zelst WH, de Beurs E, Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, van Dyck R. Prevalence and risk factors of posttraumatic stress disorder in older adults. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2003;72(6):333–342. doi: 10.1159/000073030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User’s Manual. Health Assessment Lab, New England Medical Center; Boston, MA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Hamilton NA, Potter P, Smith B. Field research on the relationship between stress and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;876:397–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Grubaugh AL, Monnier J, Suffoletta-Maierle S, Frueh BC. Trauma among female veterans. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2007;8(4):384–400. doi: 10.1177/1524838007307295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]