Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive, and irreversible fibrotic lung disease that requires long-term treatment. Given the importance of adherence to treatment and management of adverse events (AEs), patients with IPF need long-term, high-quality support in living with their condition, and adhering to therapy so they can derive maximum benefit. The IPF Care Patient Support Program (IPF Care) provides support, education, and empowerment to patients receiving pirfenidone for the treatment of IPF in Europe, through the provision of frequent, patient-managed discussions with specialist IPF nurses. In this review, we describe the structure of IPF Care in the United Kingdom (UK) and Austria, two of the longest-running IPF Care programs to date, and describe the benefits that these programs provide to patients with IPF. Analysis of results demonstrates a low rate of discontinuation from the program, and provides insight into the questions and concerns that patients express, not only with respect to pirfenidone (the only approved treatment for IPF at the time of analysis), but also in relation to other aspects of living with IPF. Pirfenidone dose modifications are common in patients in IPF Care and AEs most commonly occur early in treatment, with the majority of affected patients continuing on a stable maintenance dose. This highlights the value of the advice and support that patients receive in IPF Care regarding management of AEs and staying on treatment. Patient satisfaction was high in a survey of the UK program, with patients reporting high scores regarding ‘feeling in control of their condition’, ‘knowing what to expect from treatment’, and ‘feeling confident about how their disease is managed’. IPF Care in Europe will continue to evolve over time, striving to provide individually tailored support and patient-friendly information to improve treatment outcomes and quality of life for patients living with IPF.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-015-0183-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Patient education, Patient support, Pirfenidone, Respirology

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive, irreversible, and fatal lung disease, with an estimated median survival time of 2–5 years following diagnosis [1–5]. Studies conducted throughout Europe have estimated the prevalence of IPF to range between 1–23/100,000 persons [6–11].

Pirfenidone is an orally active, synthetic small molecule that inhibits the synthesis of transforming growth factor β and tumor necrosis factor-α, both of which have been demonstrated to play an active role in the fibrosis observed in IPF [12–17]. Pirfenidone (Esbriet®, InterMune) was the first treatment for IPF licensed for use in the Europe Union (2011), followed by Canada (2012), and the United States (2014) [18]. Pirfenidone has also been approved for marketing in Norway and Iceland, and is marketed under different trade names in China, India, Japan, South Korea, Argentina, and Mexico [18]. In October 2014, the Food and Drug Administration approved another agent, the multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor, nintedanib (Ofev®, Boehringer Ingelheim), for the treatment of IPF.

Collective evidence from five double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials has shown that pirfenidone slows disease progression, as measured by lung function and exercise tolerance [19–22]. Furthermore, a prespecified pooled analysis of the CAPACITY (ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT00287729 and #NCT00287716) and ASCEND (ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT01366209) studies at 1 year demonstrated that pirfenidone significantly decreased death from any cause [hazard ratio (HR) of 0.52 (95% CI 0.31, 0.87)], and death related to IPF [HR of 0.32 (0.14, 0.76)], versus placebo [20]. Pirfenidone is generally well tolerated, with gastrointestinal and skin-related events being the most common adverse events (AEs). Analyses from pooled clinical trial data demonstrate that the most frequently reported AEs experienced with pirfenidone, versus placebo, were nausea (32% vs. 12%), rash (26% vs. 8%), diarrhea (20% vs. 14%), fatigue (19% vs. 10%), dyspepsia (16% vs. 5%), anorexia (11% vs. 4%), headache (10% vs. 8%), and photosensitivity reactions (9% vs. 1%) [23]. However, these events rarely led to treatment discontinuation during clinical studies [20, 21].

Critically, these common AEs may first arise at the initiation of pirfenidone therapy, when patients are still adjusting to their condition and treatment plan. Longer term safety findings from a study in which patients received pirfenidone for a median duration of 2.6 years (2,059 person exposure years) are consistent with the short-term observations [24]. Recommendations for managing, or even preventing, common AEs have been developed by a panel of experts in pulmonology, gastroenterology, and dermatology [25]. Gastrointestinal events can be addressed by simple measures such as taking pirfenidone with food (preferably at the end of a meal, or in split doses throughout a meal), or in some cases temporary dose reduction/interruption with slow re-escalation to the recommended dose [25, 26]. Skin-related AEs can be prevented and/or managed primarily by patient behavioral modification, such as avoiding exposure to intense sunlight, frequently applying a broad spectrum, high-protection sunscreen, and using protective clothing (wide-brimmed hat, sunglasses, long-sleeve shirt, trousers, gloves) when outdoors or driving [25].

As with other chronic and progressive diseases, treatment adherence (defined as the extent to which a patient acts in accordance with the prescribed dose and interval of a treatment regime [27]), is of vital importance for patients to experience maximum benefit. Real-world management of adherence and patient expectation can be variable (from clinician to clinician and from patient to patient) compared with standardized clinical trials, and thus may present particular challenges for patients with IPF receiving pirfenidone. For example, patients may face difficulties in understanding and accepting this unfamiliar, chronic, irreversible disease [28]. Patients may also struggle with understanding the importance of adhering to the guidance and management plan advised by their physicians, particularly with regard to titrating their dose (following treatment initiation, pirfenidone is titrated over a 14-day period to the recommended dose of nine capsules (2,403 mg) per day [23]), taking their medication at the recommended times, and putting in place the appropriate measures to prevent and/or manage gastrointestinal and skin-related AEs. As a result, treatment persistence with pirfenidone (defined as the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy [27]) may be low.

As such, there was an unmet need for an initiative that advocates and supports treatment adherence for patients, from initiation of pirfenidone therapy through to longer term exposure. The IPF Care Patient Support Program (IPF Care) was set up to address this unmet need. In the remainder of this review, we describe the structure and objectives of IPF Care, alongside data that demonstrate the benefits that the program provides to patients with IPF. We also report the results of a patient satisfaction survey of patients in the United Kingdom (UK) participating in IPF Care. All patients and physicians who participated in IPF Care provided informed consent. This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

The IPF Care Patient Support Program

IPF Care is a patient support initiative developed by InterMune® in collaboration with IPF healthcare specialists. To date, the program has been initiated in a number of European countries, including Austria, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the UK. Although the structure and name of the program may differ from country to country, all the initiatives share the same core objectives:

Establishing a patient support system for people prescribed pirfenidone as they adjust to their diagnosis and treatment;

Providing patient education, support, and empowerment: teaching patients about the disease and how they can obtain the most benefit from pirfenidone treatment; providing counseling on living with the condition and on how to adapt their lifestyle to successfully manage both the disease and any potential AEs;

Providing support and information that complement the work of the patient’s specialist healthcare team.

The IPF Care process starts from initial pirfenidone prescription, and continues through to comprehensive patient engagement in the program. Patients have the option to remain in the program if pirfenidone is discontinued for any reason. The UK and Austria have the longest-running IPF Care programs in Europe to date; as such, the majority of patients’ experience originates from these programs. Following prescription of pirfenidone in the UK or Austria, patients are informed about IPF Care by their treating physician. If the patient wishes to be enrolled in the program, both the patient and physician provide their written, informed consent.

Structure of IPF Care in the UK and Austria

IPF Care in the UK

IPF Care was launched in the UK in May 2013. The program is managed by Partizan (London, UK), and led by two specialist IPF nurses (A. Duck and L. Pigram), who act as IPF Care Health Coaches to facilitate individually tailored support to patients through the provision of a telephone service. Patients are contacted via telephone by the specialist nurse at mutually agreed times.

The first call from the nurse is lightly scripted: the nurse will ask patients how they are coping with their condition and with treatment. The nurse will take the opportunity during this initial contact to ensure that the patients have understood the instructions from the physician regarding how and when to take their pirfenidone dose, and how to up-titrate during the first few weeks. There will also be discussion with the patient regarding any treatment-related AEs they may be experiencing, and guidance is provided by the nurse on how the patient can prevent and/or self-manage these AEs.

Following the initial call, there is a follow-up call every week or every fortnight for the first month. Once the patient is established on therapy, the timing and frequency of subsequent calls are decided upon by the nurse and patient together, depending on how many calls the patient feels he/she would need (or like) to receive, and how much support and education the nurse feels is required to help the individual patient adhere to the treatment plan, persist with therapy, and adequately manage the disease. For some patients, this may result in monthly follow-up calls; others may require communication less frequently. The IPF nurses not only have frequent communication with patients, but can also directly contact treating physicians regarding individual patients, particularly with regards to discussion of dose modification due to emergent AEs and/or changes in patient circumstances.

In addition to this telephone support network, patients in the program in the UK are also provided with patient-tailored information booklets, including ‘IPF—a guide for patients’, ‘A guide to your treatment with Esbriet’, and ‘Introducing IPF Care’. Patients also receive a ‘My Health Journal’ booklet, that provides practical tips for living with IPF and taking pirfenidone, in addition to an appointment tracker and notes sections to help patients highlight important points, capture any concerns or questions they wish to raise with their healthcare team, and ultimately self-manage their condition as required.

IPF Care in Austria

IPF Care was launched in Austria in April 2013. At present, all patients are supported by one dedicated specialist IPF nurse (S. Toescher). Although similar to the UK program in a number of ways, one key difference in the Austrian program is the use of face-to-face meetings with the nurse in the patient homes (or other suitable location) throughout the program. Initially, the nurse contacts the patient via telephone, to ascertain if the patient would be open to a home visit, and to put plans in place to facilitate this meeting, such as finding suitable dates, and asking if any other individuals (i.e., family members, friends, care givers) would like to attend. This initial telephone conversation is also the first opportunity for the nurse to assess patient condition, patient knowledge of IPF, initial experience and understanding of the pirfenidone dose titration schedule, and any concerns about potential AEs. The nurse will explain that all these topics will be discussed in greater detail during the initial face-to-face meeting, and will ask the patient if there are any other specific topics that they would like to cover at the meeting, so that adequate preparation can be made.

The initial face-to-face meeting usually lasts between 1 and 2 h, and ideally occurs before the patient has initiated pirfenidone treatment [or as early as possible after treatment initiation (within 1–2 weeks)]. In this way, the patients receive the support and encouragement of the program from the very beginning of their pirfenidone experience. This initial meeting with the patient allows the nurse to assess a number of important points, including: (1) that the patient has received adequate information from the treating physician to understand IPF as a disease, and how it will potentially affect their life, and (2) that the patient is aware of how and when to take pirfenidone, and how to up-titrate the doses during the first few weeks. The nurse will also take the opportunity during this initial face-to-face contact to educate the patient on the additional measures that can be adopted to prevent or manage the gastrointestinal and skin-related AEs (such as splitting the dose, taking doses during or at the end of a meal, and using additional sun protection), and to emphasize the importance of adhering to these measures so that they can persist with therapy and experience the maximum benefit of pirfenidone treatment. The patients will also be made aware of any additional sources of information and support that may be available to them in their community. Vital signs are monitored and recorded during the initial meeting, and at all subsequent home visits (if they occur).

Following the initial face-to-face meeting, the nurse contacts the patient via telephone every fortnight for the first month, then every month for the following 3 months, and thereafter (if the patient is comfortable with less frequent communication) every 4–6 weeks, irrespective of whether the patient is still receiving pirfenidone. During each telephone call, the patient is given the option of additional face-to-face meetings with the nurse, which can occur every 6–8 weeks if required. Each patient communication (from the initial face-to-face meeting to follow-up telephone calls and/or subsequent home visits) is individually planned and prepared.

A face-to-face meeting lasts on average 1–2 h, and a telephone discussion 20–30 min, but may take longer if there are many issues to discuss, or if additional family members or friends wish to take part. After every communication with the patient, the nurse fills in a ‘visit log’, which describes what was discussed, including any issues with the disease or with treatment, and any AEs experienced and actions taken to address them. The patient is encouraged to bring this visit log to upcoming physician or hospital appointments. If a patient discontinues from the program, there are no outbound calls and no visits organized, unless the patient requests them. Patients who no longer receive pirfenidone (for example, those who have received lung transplants) are still considered to be in the program and still receive support from the program, unless they opt out.

As with the UK program, the IPF Care nurse in Austria has the option (following patient permission) to contact a treating physician and discuss dose modification if the patient is experiencing any treatment-related AEs. In addition to home visits, Austrian patients also received an ‘IPF Nurse folder’, which contains the patient and physician consent forms, a patient information leaflet and more information on the program. Furthermore, once a year, local IPF meetings are arranged in Austria. At these meetings, patients have the opportunity to bring along family members and friends, and meet other patients and IPF experts. During the first 6 months of 2014, three IPF Care meetings were held across different regions of Austria, with a total of 42 participants.

Benefits of IPF Care as Observed in the UK and Austrian Programs

A key element of IPF Care as observed from the UK and Austrian programs is that calls and/or visits are open, patient-managed discussions, with the content and direction of the conversation dictated by the individual’s circumstances and needs. This focusses the communication on topics relevant to the patient at that specific point in time, and empowers patients to take control and be the integral driver in the management of their disease. The IPF Care nurses in both the UK and Austria report that patients begin to share their ‘IPF story’ with the nurse from the first initial telephone contact, posing disease-related questions regarding etiology and disease management, speaking about their fears and anxieties for the future, as well as discussing more practical aspects such as blood tests and physician visits. Patients also often volunteer information regarding their personal circumstances, hobbies and family support situation; this information can be valuable to the nurse in building a solid relationship with the patient.

IPF Care provides flexibility with regard to the duration of these conversations, as patients continue on therapy. The length of follow-up calls/visits is determined by the patient–nurse interactions. This allows the nurse the opportunity to reinforce AE management and prevention measures and to assess that the patient has understood the information from the treating physician regarding titration. Similarly, the patient has the opportunity to highlight topics they would like explained or discussed in greater detail. As all follow-up calls in IPF Care are patient-led, every call is individualized. Patients have different experiences and outlooks, as they continue to live with and manage this chronic condition. Some patients are open and positive, telling the nurse about their family and friends and describing changes in their own lives (both disease-related and unrelated) since the last communication. Other patients may be looking for the opportunity to talk to a friendly and understanding confidant about aspects of their lives and condition, regarding issues that they say they do not wish to ‘bother’ their physician or healthcare team about. Follow-up calls also allow for more practical discussions, for example about oxygen use, prevention of AEs and general disease awareness and management.

A positive aspect that has emerged from the programs in both the UK and Austria is the role of the nurse in facilitating and enhancing communication between the patient and the treating physician. In this role, the nurse has a close relationship and frequent communication with the patient. They are often aware of situations before the treating physician, and can therefore inform the healthcare team directly, or encourage the patient to contact the physician for advice. For example, during a regular IPF Care conversation, the patient may casually mention an upcoming holiday. In such a case it may be appropriate for the nurse to directly update the treating physician with this information. This facilitates appropriate communication and discussion with the patient at the next scheduled clinic visit, and helps the physician to reinforce the need for extra skincare protection precautions if outdoors or driving during the vacation, and/or to be mindful of taking pirfenidone with food, even if mealtimes or diet are altered during the time away. Similarly, the nurse can inform the physician of any concomitant medications for other conditions that the patient may be taking (which may have been prescribed elsewhere) since initiating pirfenidone. The patient may not always remember, or think it is necessary, to update the physician with these details, but the frequent and open communication that the nurse has established with the patient facilitates the exchange of potentially important information. The nurse can then relay information to the treating physician to ensure that they have a more ‘complete picture’ of the patient, and that they can make informed decisions regarding treatment and overall management plan.

A further example of the benefit of this close patient–nurse–physician relationship relates to pirfenidone dose titration. During the initial titration phase, or during a re-titration phase following temporary dose decrease/interruption, the close communication with the patient means that the nurse can inform and discuss potential management options with physicians when patients are struggling with dose titrations and experiencing AEs, which helps facilitate early physician assessment and implementation of appropriate measures.

Findings from IPF Care in the UK

Low Rates of Discontinuation from the Program

As of the end of October 2014 (18 months since launch), 465 patients had been enrolled in IPF Care in the UK. The majority of patients (332/465 patients; 71%) were on pirfenidone therapy for less than 30 days at the time of enrollment into the program.

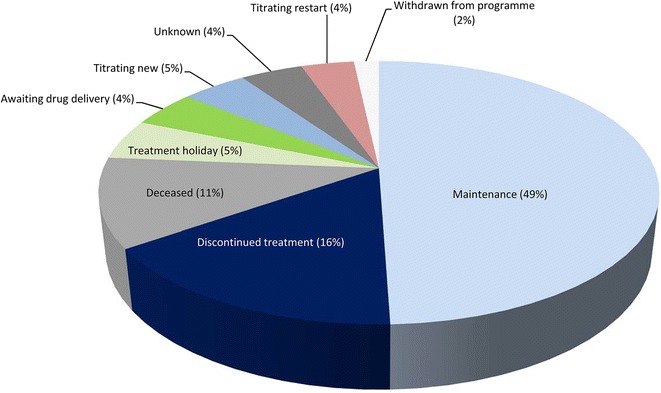

Of the 465 patients enrolled, 71 % (332 patients) remain in the program at the time of reporting (November 5, 2014). The average time on treatment for all enrolled patients was 239 days, with an average of 4.1 calls made per patient. The most common reasons for no longer participating in the program were permanent discontinuation of pirfenidone [n = 74 (16%)] and patient death [n = 51 (11%)]. Eight patients (2%) withdrew from the program for other reasons. Approximately half (49%) of all enrolled patients were on maintenance therapy (i.e., successfully titrated to receive a stable pirfenidone dose) at time of reporting, with smaller proportions of patients titrating treatment (9%) or temporarily not receiving treatment (5%), as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Latest patient status for all patients enrolled in IPF Care in the UK (N = 465). Maintenance: includes patients who have successfully titrated to receive a stable pirfenidone dose. Treatment holiday: includes patients who are temporarily not receiving pirfenidone. Titrating restart: includes patients who are starting titration again, after a break in treatment or following intolerance to the full dose. Titrating new: includes patients who are continuing with their first titration attempt

The most common reasons for stopping treatment and/or withdrawing from the program (aside from death) were AEs [n = 35 (8%)] and worsening symptoms [n = 12 (3%)], followed by treatment ‘not working’ [n = 5 (1%)], transplant [n = 3 (<1%)], wrong diagnosis [n = 1 (<1%)], other health issues [n = 1 (<1%)], and ‘other’ [n = 20 (4%)], with no reason specified for some patients [n = 5 (1%)]. Decisions to permanently stop treatment and/or withdraw from the program were more often led by the physician [n = 62 (13%)] as opposed to the patient [n = 15 (3%)] [not specified: n = 5 (1%)] with most withdrawals occurring during the second and third months of therapy [n = 24/82 (29%)], after patients had participated in, on average, 3.2 calls.

Patients Discuss a Wide Range of Topics, Not Always Pertaining to Pirfenidone Treatment

Data have been analyzed to investigate how the program is performing against its key objectives, and to ascertain what benefits it is providing for patients. A total of 823 calls (representing 239 patients) were analyzed. The average initial call length was 20.4 min and the average follow-up call length 19.7 min. A list of individual topics was identified (Table 1), and the frequency with which these topics were discussed during the calls was calculated.

Table 1.

Frequency of individual topics discussed during calls in IPF Care in the UK (823 calls assessed)

| Individual topics discussed | Frequency | Higher level topic |

|---|---|---|

| Nausea | 67 | Gastrointestinal |

| Loss of appetite | 66 | |

| Weight loss | 31 | |

| Indigestion/gastric reflux | 26 | |

| Diarrhea | 21 | |

| Vomiting | 10 | |

| Loss of taste | 6 | |

| Constipation | 5 | |

| Rash from sun | 30 | Skin |

| Itchiness from sun | 12 | |

| Redness from sun | 8 | |

| Flushing/feeling hot | 7 | |

| Rash (not from sun) | 5 | |

| Itchiness (not from sun) | 5 | |

| Redness (not from sun) | 0 | |

| Elevated LFTs | 81 | Liver or blood tests |

| Abnormal INR (patients on warfarin) | 3 | |

| Lethargy/tiredness | 85 | Tiredness |

| Dizziness | 19 | |

| Sleeplessness | 15 | |

| Shortness of breath | 80 | SOB/cough |

| Cough | 44 | |

| Oxygen | 132 | Non-pirfenidone treatment relateda |

| Talking about test results (e.g., lung function tests, chest X-rays and echocardiograms) | 114 | |

| Homecare/drug delivery | 105 | |

| Patient reports: deterioration/fear for future if drug ‘does not work’ | 47 | |

| Going on holiday/vacation | 47 | |

| Questions on exercise/Is it dangerous to be breathless? | 19 | |

| Questions on transplant: am I suitable for transplant? What are the criteria for transplant? | 25 | |

| Patient expectation of drug | 10 | |

| Wearing sunscreen | 58 | Coping strategies |

| Reduced doses | 48 | |

| Treatment holidays | 45 | |

| Antiemetics (maxolon or domperidone) | 28 | |

| Treatment stopped | 27 | |

| Taking drug with food | 21 | |

| Patient stories | 20 | |

| Patient stops treatment | 10 | |

| Splitting capsules across meals | 8 | |

| Patient reduces dose | 7 | |

| Other illness/medicationsb | 159 | Otherc |

| Chest pain or infection | 23 | |

| Mood/depression/anxiety | 22 | |

| Support groups and pulmonary rehabilitation | 18 | |

| Swelling | 5 | |

| Headache | 5 | |

| Phlegm | 3 | |

| Patient concerns about drug | 3 | |

| Difficulty in chewing food | 2 |

INR international normalization ratio, LFT liver function tests, SOB shortness of breath

a Topics may be related to IPF, but not specifically to pirfenidone treatment

b Includes a number of illnesses and associated treatments including renal stones, clots, insect bites, antibiotics, omeprazole, oramorph, and doxycycline

c Includes individual terms that do not fall into any other identified higher level topic. May contain a mixture of terms both related and unrelated to pirfenidone treatment and/or IPF

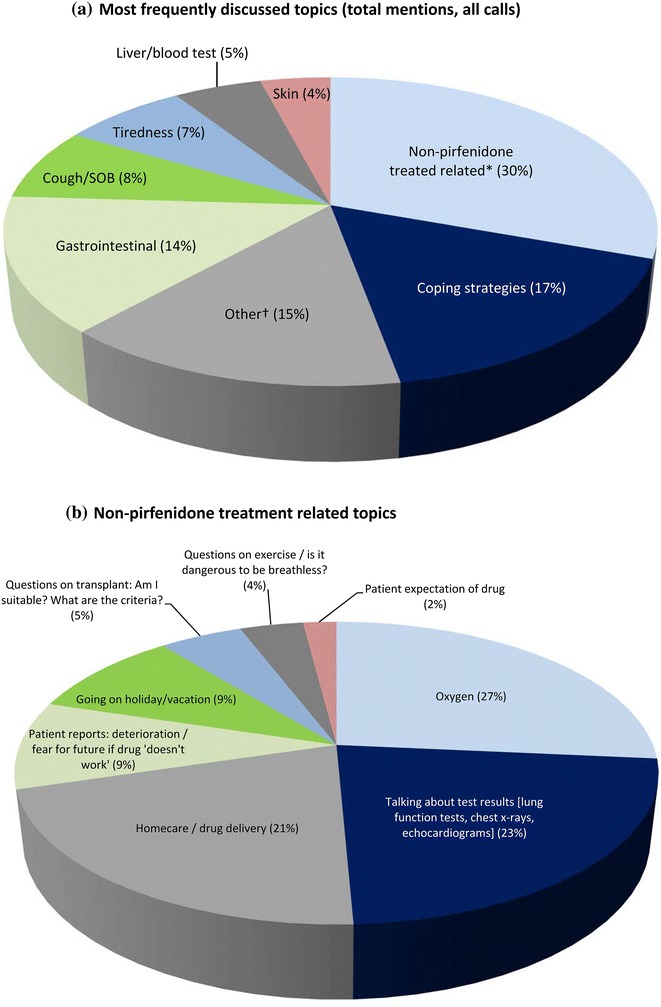

The most frequently discussed topics (total mentions, all calls) during these conversations were not directly related to pirfenidone treatment (Fig. 2a). Patients were more likely to talk about test results (lung function tests, chest X-rays, and echocardiograms), oxygen and homecare/drug delivery (Fig. 2b). Other illnesses and associated treatments were also frequently discussed during the calls (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Topics discussed during calls in IPF Care in the UK (823 calls assessed): a most frequently discussed topics (total mentions, all calls); b non-pirfenidone treatment-related topics. *Topics may be related to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), but not specifically to pirfenidone treatment; †Includes individual terms that do not fall into any other identified higher level topic. May contain a mixture of terms both related and unrelated to pirfenidone treatment and/or IPF

AEs Occurred Early in Treatment, But the Majority of Affected Patients Continued on a Stable Maintenance Dose of Pirfenidone

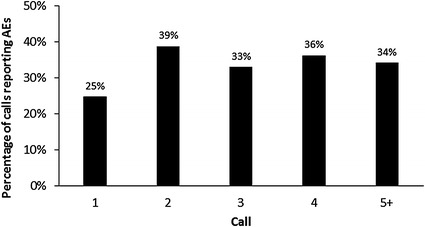

In total, 267/823 (32%) calls included a mention of at least one AE. When analyzed by each individual communication, patients more frequently reported AEs from the second call (which would typically take place 1–2 months after treatment initiation) onwards (Fig. 3). The first call will usually take place while the patients are up-titrating their dose over a 14-day period (minimum). AEs are less likely to occur during this titration period, but may start to emerge once patients are receiving the maximum recommended daily dose of nine capsules, which would usually coincide with the timing of the second call. If an AE is reported during a conversation, a follow-up call to the patient will be made within 1–2 weeks to check if the self-management strategies advised by the nurse are effective. This accounts for the high percentage of subsequent calls discussing AEs as shown in Fig. 3. The occurrence of AEs early in treatment observed here is in agreement with previous safety assessments of pirfenidone in a clinical setting, which report that gastrointestinal and skin-related AEs tend to occur within the first 6 months of treatment and decrease in frequency over time [24].

Fig. 3.

Adverse events (AEs) reported in IPF Care in the UK by individual call (823 calls assessed)

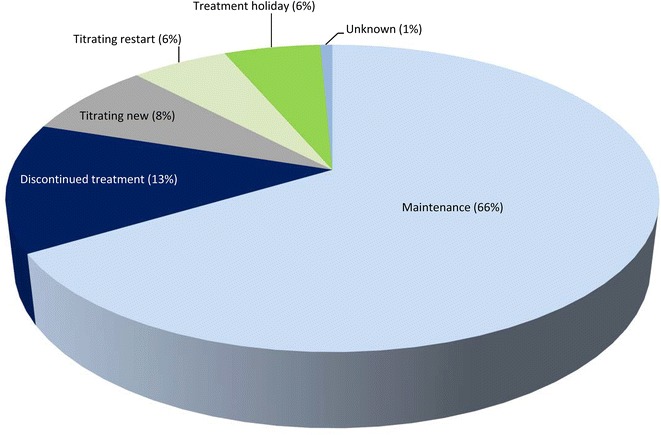

When analyzed by number of patients, 140/239 patients (59%) reported at least one AE during these calls. Of these 140 patients who reported at least one AE, the majority (66%) remained on maintenance therapy, with a smaller proportion (13%) discontinuing treatment (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Latest patient status for all patients who reported ≥1 adverse event (N = 140) in IPF Care in the UK. Maintenance: includes patients who have successfully titrated to receive a stable pirfenidone dose. Treatment holiday: includes patients who are temporarily not receiving pirfenidone. Titrating restart: includes patients who are starting titration again, after a break in treatment or following intolerance to the full dose. Titrating new: includes patients who are continuing with their first titration attempt

Patient-Reported Satisfaction with the Program was High

Over the past 20 years, patient satisfaction surveys have gained increasing acceptance as sources of information for assessing and improving healthcare resources [29]. Research indicates that better ‘patient care experiences’ are associated with higher levels of adherence to prevention and treatment interventions, better clinical outcomes, better patient safety within hospitals, and less healthcare utilization [30]. A survey assessing patient satisfaction in IPF Care was performed to ascertain how patients feel about the program with regard to disease management and education. Patients diagnosed with IPF in the previous 12 months, who were participating in IPF Care for longer than 4 weeks and who were on maintenance therapy at the last point of contact, were sent a questionnaire by post consisting of eight questions related to their experience with the program (Fig. 5). Of the 100 survey questionnaires sent to patients, 44 completed responses were received.

Fig. 5.

The IPF Care patient support program survey in the UK

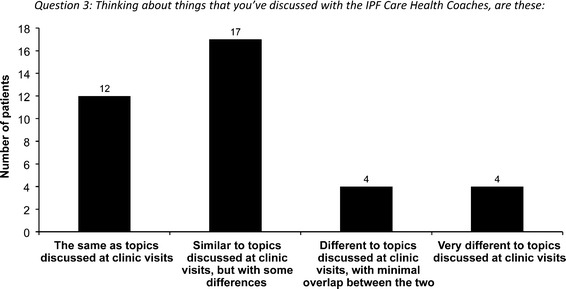

Patient ratings suggested that IPF Care provided improvements in terms of feeling in control of their condition, knowing what to expect from treatment, and feeling confident about how their disease was managed (Table 2). The majority of patients also reported that the topics discussed with the specialist nurses were ‘the same’ or ‘similar’ to the topics discussed at clinic visits (Fig. 6). However, general feedback suggested that patients were more comfortable and relaxed discussing these topics over the phone with the nurse, as opposed to in a hospital or clinic environment. When asked to rate the importance of having specialist nurses as the IPF Health Coaches (1 = not at all important; 10 = essential), the average score was 8.7 (range 1–10; mode 10).

Table 2.

Patient perception regarding disease, treatment and management before and after participation in IPF Care in the UK

| Statement | Parameter | Question 1: Before IPF Care | Question 2: As a result of IPF Care |

|---|---|---|---|

| I feel in control of my condition | Mean | 4.5 | 6.5 |

| Mode | 4 | 8 | |

| Range | 1–10 | 2–10 | |

| I know what to expect from treatment | Mean | 5.5 | 7.7 |

| Mode | 5 | 9 | |

| Range | 1–10 | 1–10 | |

| I feel confident about how my disease is managed | Mean | 5.6 | 7.5 |

| Mode | 5 | 8 | |

| Range | 1–10 | 1–10 |

Question 1: Thinking back to before you joined the IPF Care program, please rate the following (1 = low; 10 = high)

Question 2: And how would you rate the following now, as a result of the IPF Care program (1 = low; 10 = high)

Fig. 6.

Similarity of topics discussed during IPF Care telephone discussions versus topics discussed during clinic visits (IPF Care UK survey; N = 37). Two patients did not answer the question, one patient answered ‘none of the above’, and four patients provided multiple answers and were therefore all excluded from analysis

Patients were asked to rate their agreement with the statement “I have stayed on Esbriet treatment longer than I would have done without the support of the IPF Care program” (1 = completely disagree, 10 = completely agree). The average score reported was 7.0 (range 1–10; mode 10). When asked to rate if they thought the program would be useful to other patients taking Esbriet (1 = extremely unlikely, 10 = definitely), the average score was 8.7 (range 5–10; mode 10). Patients were also asked to provide their reasons for the score they gave for this last question. Reasons provided by patients included: “Knowing support is a phone call away makes me feel less panicky”, “It provides a human element”, “It is helpful to know someone is keeping an eye on you”, “Being able to speak to someone over the phone about my problems has been very reassuring, rather than having to wait until my next clinic visit”, “The extra support is reassuring”, “There is always help on the end of the phone when you are struggling with breathing”, “Gives you more confidence and peace of mind”, “It enables me to discuss all aspects of IPF and ask questions that may seem insignificant”, “They have changed my life, they have given me freedom”, and “They put my mind at rest regarding the side effects”.

At the end of the survey, patients were asked to provide any other feedback about IPF Care. The following is a selection of comments: “Feels easier to ask trivial things—which are still important—of a nurse who rings up like a friend”, “Care and support is excellent”, “The IPF nurses are well trained”, “I like talking to my support nurse”, “I feel more relaxed talking to IPF Care support, as hospital environment does not always help you relax”, “With the lack of knowledge about this disease, any information is welcome”, “Staff are extremely helpful and have time to talk”, and “I feel this is very important to all patients”.

It should be noted that as only patients on maintenance therapy were chosen to participate in the survey, this may represent a selection bias. These patients were tolerating the full dose of pirfenidone with little or no AEs, and may therefore not have received as many calls from the IPF Care nurse as patients struggling with tolerating the full pirfenidone dose.

Findings from IPF Care in Austria

At time of writing, there are currently 69 patients in IPF Care in Austria, which is estimated to represent approximately 40% of all patients prescribed pirfenidone in the country.

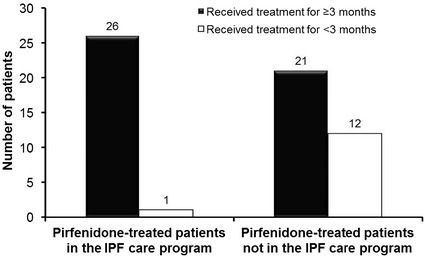

Dose Modifications are Common in IPF Care and Enrolled Patients Stay on Treatment Longer than Patients Receiving Pirfenidone Outside of the Program

An 8-month period (November 2013–June 2014) was assessed in which 27 pirfenidone-treated patients were enrolled in IPF Care (from November 2013–March 2014) in Austria. Dose modifications were common in these patients. Five patients (18.5%) had a prolonged titration phase, 3 patients (11.1%) a permanent dose modification, and 3 patients (11.1%) a dose reduction followed by a subsequent up-titration to the recommended full dose. These treatment modifications were decided by the treating physician, but in close contact with the IPF Care nurse.

The benefit of the program in Austria with regard to patients remaining on treatment is shown in Fig. 7. Almost all 27 patients who started pirfenidone with the support of the IPF Care nurse stayed on treatment for at least 3 months. Only 1 out of 27 patients in IPF Care discontinued treatment during the first 3 months of therapy, compared with a discontinuation rate of 36% (12/33) in an unsupported group of patients receiving pirfenidone outside of the program.

Fig. 7.

Patients remaining on treatment for ≥3 months in IPF Care in Austria

Placing Our Observations in Context: Findings From Other Patient Support Programs

To place our observations in context, and to support the value of patient education and empowerment in improving treatment adherence and patient outcomes, we reviewed previous publications on patient support programs, both in IPF and in other chronic diseases. A small, pirfenidone access program (operating on the basis of named patient supply) served as a precursor to IPF Care in the UK [31]. In this real-world analysis of 40 patients with IPF, six patients (15%) discontinued during the first 6 months of treatment. No patients discontinued during the subsequent 10 months. The authors of the analysis largely attribute this finding to the implementation of patient education and communication measures, including: (1) a monthly specialist nurse review that occurred during the first 3 months of treatment to assess and reinforce AE avoidance measures, and (2) patients given contact numbers and encouraged to speak with a specialist nurse if they experience any AEs. This meant that appropriate measures (e.g., dose reduction, temporary dose discontinuation, additional treatment of AEs) could be advised without delay to rapidly alleviate AEs.

In Canada, there is a very similar patient support initiative to IPF Care, called the INSPIRATION program, managed by InterMune® [32]. An analysis of data from this program assessed the persistency and adherence of 308 enrolled patients receiving pirfenidone. Specialist nurses contacted patients via the telephone on a weekly (first month), bi-weekly (next two months) and quarterly (month 4 onwards) basis, with patients self-reporting their capsule intake. After 6 months of drug exposure, the persistency rate (patients remaining on drug) was 81%, with the main patient-reported reasons for discontinuation predominantly AEs of gastrointestinal and skin-related events. The adherence rate (patients receiving >80% therapeutic dose of 2,403 mg/day) at 6 months was 83%. The authors of the analysis attribute the high 6-month persistency and adherence rates to the close nurse–patient follow-up facilitated by the INSPIRATION program.

Patient support-type programs have also been implemented in a number of other chronic illnesses to improve adherence to medication and disease management, and to empower self-management skills. Indeed, the benefits of such a program have been demonstrated in another debilitating respiratory disorder: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Data from 141 patients in a patient-centric COPD program (that imparted self-management principles, and provided telephonic nursing outreach and an action plan for symptom exacerbation) were compared with data from the same number of patients who accessed care from their physician or through emergency departments (control group) [33]. At 1 year, physician visits were significantly less frequent for patients in the program compared with the control group. Hospital admission, bed days and emergency department visits also showed a downward trend for patients in the program. Another COPD study assessed the relationship between self-management abilities, quality of chronic care delivery, and patient wellbeing of 548 individuals enrolled in a COPD care program in The Netherlands [34]. A multilevel random-effects model demonstrated a significant relationship between quality of chronic care delivery and the wellbeing of patients. Interestingly, self-management abilities were also found to have a significant positive relationship to patient wellbeing.

One of the largest assessments of disease management programs described to date comes from an analysis of data from programs for asthma (N = 23,793), congestive heart failure (N = 4,092), and diabetes (N = 29,604), for patients in the United States Department of Defense Military Health System (TRICARE) [35]. These voluntary, opt-out, patient-centered programs provide patients with telephone-based consultations with a care manager, and educational materials and newsletters specific to patient needs. Improvements in patient outcomes included reduced inpatient days and medical costs, with increased proportions of patients receiving appropriate medications and tests. A survey assessing patient satisfaction showed that the majority of respondents (≥85%) rated their overall experience as ‘good’, ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’. The majority of patients (≥60%) also ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that the program has helped them improve their life, and helped them better manage different aspects of their disease.

Taken together, these studies of disease management and patient support programs across a number of conditions demonstrate the value of patient education and empowerment with respect to numerous endpoints, including treatment adherence and persistency, patient outcomes, quality of life and wellbeing, and healthcare utilization and medical costs. The observations from IPF Care described in the present article support the previous findings from other disease management programs with regard to the benefit of a patient-centric approach for long-term, chronic conditions.

Conclusions

IPF Care in Europe provides individually tailored support and patient-friendly information so that patients develop a better understanding of their chronic condition. Through close and frequent communication with specialist nurses, patients receive practical advice on how to cope with IPF on a daily basis, and how to manage symptoms, treatment and AEs over both the short and long term. The ultimate goal of the program is to improve treatment outcomes and the overall quality of life for patients living with IPF.

As observed from IPF Care in the UK and Austria, in addition to observations from other disease management initiatives, patient support programs are of great value in the management of chronic diseases. IPF Care complements and enhances healthcare systems by providing patients with the opportunity to discuss any issues—not only relating to pirfenidone, but on any topic important to them—which can often be overlooked during formal, clinical consultations. Observations from the patient satisfaction survey of patients in IPF Care in the UK indicate that patients feel positive about their involvement in the program, that they believe it to be an important and helpful outlet, and they feel better educated and more confident and supported in their disease management as a result of IPF Care.

The limitations of the IPF Care data analysis from the UK and Austrian programs should be considered when interpreting the findings. A relatively small number of patients were included in the analyses, no set study design or independent evaluation was implemented for either program, and a control group of pirfenidone-treated patients outside IPF Care was not considered in the analysis of UK data which could potentially contribute to a biased interpretation of results. Furthermore, it should be acknowledged that the additional benefits that IPF Care provides to patients are variable and dependent on the level of support already available from their specialist healthcare team, which for a number of patients may be sufficient. We believe, however, that our findings demonstrate that IPF Care is of added value to patients who require outside support complementary to that currently provided by their healthcare teams.

IPF Care established in countries throughout Europe will continue to evolve and develop over time, striving to provide the best possible support for patients with IPF in the day-to-day management of this chronic, progressive disease.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published. The authors wish to acknowledge Róisín O’Connor, inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare Ltd., for medical writing and editorial assistance, funded by InterMune® International AG (Muttenz, Switzerland), and Josh Taylor, Partizan, for assistance with analysis of the IPF Care UK data, also funded by InterMune® International AG. Article processing charges were funded by InterMune® International AG.

Conflict of interest

Annette Duck is a part-time consultant/contractor for Partizan (funded by InterMune UK and Ireland to run the IPF Care program in the UK) and has also received speaker honoraria and support for conference attendance from InterMune, and advisory board honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim. Lucy Pigram is a part-time consultant/contractor for Partizan (funded by InterMune UK and Ireland to run the IPF Care program in the UK). Peter Errhalt has received speaker honoraria from InterMune and Boehringer Ingelheim and has attended advisory boards for InterMune and Boehringer Ingelheim. Deeba Ahmed is an employee of InterMune. Nazia Chaudhuri has received project grants from InterMune UK, has attended advisory boards for InterMune UK, and has received support for attendance of conferences from Boehringer Ingelheim and InterMune UK.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

All patients and physicians who participated in IPF Care provided informed consent. This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.Collard HR, Moore BB, Flaherty KR, et al. Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:636–643. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-463PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim DS, Collard HR, King TE., Jr Classification and natural history of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:285–292. doi: 10.1513/pats.200601-005TK. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ley B, Collard HR, King TE., Jr Clinical course and prediction of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:431–440. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-0894CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meltzer EB, Noble PW. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:8. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gribbin J, Hubbard RB, Le Jeune I, Smith CJ, West J, Tata LJ. Incidence and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and sarcoidosis in the UK. Thorax. 2006;61:980–985. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.062836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodgson U, Laitinen T, Tukiainen P. Nationwide prevalence of sporadic and familial idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence of founder effect among multiplex families in Finland. Thorax. 2002;57:338–342. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.4.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karakatsani A, Papakosta D, Rapti A, et al. Epidemiology of interstitial lung diseases in Greece. Respir Med. 2009;103:1122–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Navaratnam V, Fleming KM, West J, et al. The rising incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the UK. Thorax. 2011;66:462–467. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.148031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomeer MJ, Costabe U, Rizzato G, Poletti V, Demedts M. Comparison of registries of interstitial lung diseases in three European countries. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2001;32:114s–118s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Plessen C, Grinde O, Gulsvik A. Incidence and prevalence of cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis in a Norwegian community. Respir Med. 2003;97:428–435. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2002.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grattendick KJ, Nakashima JM, Feng L, Giri SN, Margolin SB. Effects of three anti-TNF-alpha drugs: etanercept, infliximab and pirfenidone on release of TNF-alpha in medium and TNF-alpha associated with the cell in vitro. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:679–687. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu H, Drew P, Gaugler AC, Cheng Y, Visner GA. Pirfenidone inhibits lung allograft fibrosis through l-arginine-arginase pathway. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1256–1263. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakayama S, Mukae H, Sakamoto N, et al. Pirfenidone inhibits the expression of HSP47 in TGF-beta1-stimulated human lung fibroblasts. Life Sci. 2008;82:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oku H, Nakazato H, Horikawa T, Tsuruta Y, Suzuki R. Pirfenidone suppresses tumor necrosis factor-alpha, enhances interleukin-10 and protects mice from endotoxic shock. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;446:167–176. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01757-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oku H, Shimizu T, Kawabata T, et al. Antifibrotic action of pirfenidone and prednisolone: different effects on pulmonary cytokines and growth factors in bleomycin-induced murine pulmonary fibrosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;590:400–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaefer CJ, Ruhrmund DW, Pan L, Seiwert SD, Kossen K. Antifibrotic activities of pirfenidone in animal models. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20:85–97. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00001111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.InterMune (2014) Products–about pirfenidone. http://www.intermune.com/products. Accessed Dec 2014.

- 19.Azuma A, Nukiwa T, Tsuboi E, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:1040–1047. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-571OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King TE, Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2083–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;377:1760–1769. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taniguchi H, Ebina M, Kondoh Y, et al. Pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:821–829. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00005209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esbriet (pirfenidone) (2014) Summary of product characteristics: Esbriet 267 mg hard capsules. http://www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/26942/SPC/Esbriet+267+mg+hard+capsules/. Accessed Nov 2014.

- 24.Valeyre D, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Comprehensive assessment of the long-term safety of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology. 2014;19:740–747. doi: 10.1111/resp.12297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costabel U, Bendstrup E, Cottin V, et al. Pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: expert panel discussion on the management of drug-related adverse events. Adv Ther. 2014;31:375–391. doi: 10.1007/s12325-014-0112-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Y, Yap SR, Seiwert SD, Pan L. Nonclinical studies suggest simple strategies to further improve the GI tolerability of Pirfenidone. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(A38):A1420. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health J Int Soc Pharma Outcomes Res. 2008;11:44–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giot C, Maronati M, Becattelli I, Schoenheit G (2013) Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an EU patient perspective survey. Curr Respir Med Rev 9:112–9(8).

- 29.Al-Abri R, Al-Balushi A. Patient satisfaction survey as a tool towards quality improvement. Oman Med J. 2014;29:3–7. doi: 10.5001/omj.2014.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anhang Price R, Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med Care Res Rev. 2014;71(5):522–554. doi: 10.1177/1077558714541480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaudhuri N, Duck A, Frank R, Holme J, Leonard C. Real world experiences: pirfenidone is well tolerated in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med. 2014;108:224–226. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacQuarrie JL, Lebel F. Pirfenidone use in clinical practice: analysis of data from a Canadian patient support program for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (INSPIRATION) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:A1428. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chuang C, Levine SH, Rich J. Enhancing cost-effective care with a patient-centric chronic obstructive pulmonary disease program. Popul Health Manag. 2011;14:133–136. doi: 10.1089/pop.2010.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. The relationship between self-management abilities, quality of chronic care delivery, and wellbeing among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in The Netherlands. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:209–214. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S42667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dall TM, Askarinam Wagner RC, Zhang Y, W Yang, Arday DR, Gantt CJ. Outcomes and lessons learned from evaluating TRICARE’s disease management programs. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16:438–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.