Abstract

Cysteine (Cys) oxidation is a crucial post-translational modification (PTM) associated with redox signaling and oxidative stress. As Cys is highly reactive to oxidants it forms a range of post-translational modifications, some that are biologically reversible (e.g. disulfides, Cys sulfenic acid) and others (Cys sulfinic [Cys-SO2H] and sulfonic [Cys-SO3H] acids) that are considered “irreversible.” We developed an enrichment method to isolate Cys-SO2H/SO3H-containing peptides from complex tissue lysates that is compatible with tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). The acidity of these post-translational modification (pKa Cys-SO3H < 0) creates a unique charge distribution when localized on tryptic peptides at acidic pH that can be utilized for their purification. The method is based on electrostatic repulsion of Cys-SO2H/SO3H-containing peptides from cationic resins (i.e. “negative” selection) followed by “positive” selection using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography. Modification of strong cation exchange protocols decreased the complexity of initial flowthrough fractions by allowing for hydrophobic retention of neutral peptides. Coupling of strong cation exchange and hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography allowed for increased enrichment of Cys-SO2H/SO3H (up to 80%) from other modified peptides. We identified 181 Cys-SO2H/SO3H sites from rat myocardial tissue subjected to physiologically relevant concentrations of H2O2 (<100 μm) or to ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury via Langendorff perfusion. I/R significantly increased Cys-SO2H/SO3H-modified peptides from proteins involved in energy utilization and contractility, as well as those involved in oxidative damage and repair.

Cysteine (Cys)1 is an integral site for protein post-translational modification (PTM) in response to physiological and pathological stimuli. Numerous studies have identified roles for biologically reversible Cys PTM, including disulfides, S-nitrosothiols, and sulfenic acids (Cys-SOH), in the regulation of protein function during redox signaling (reviewed in (1, 2)). Additionally, Cys can be oxidized in pathologies associated with oxidative stress (e.g. neurodegeneration, cancer, and cardiovascular disease (2)). Various redox proteomics methods exist for enrichment of these reversibly oxidized Cys, based on reduction to the thiol and then capture by: 1) alkylation with a chemical tag (e.g. isotope coded affinity tags) (3–6); 2) thiol-disulfide exchange (7–10); or 3) heavy metal ion chelation (11, 12). Oxidative Cys PTMs with predominantly no known means of enzymatic reduction have also been identified. These “over” or “irreversibly” oxidized Cys PTM (sulfinic [Cys-SO2H] and sulfonic [Cys-SO3H] acids) are primarily associated with oxidative stress. Only one example of reversible Cys-SO2H modification has been characterized—in peroxiredoxins (Prx) by the ATP-dependent sulfiredoxin (Srx)(13); however, Srx is not thought to reduce Cys-SO2H in other proteins, and no mechanism has yet been found for Cys-SO3H reduction. At basal levels, ∼1–2% of Cys exist as Cys-SO2H/SO3H (14), and the RSO2H modification has functional significance in some proteins (e.g. DJ-1 is activated in Alzheimer's disease by Cys-SO2H at Cys-106) (15).

Cys-SO2H/SO3H are produced via sequential oxidation of Cys-SOH, which itself is formed because of Cys thiol oxidation by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS), such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or peroxynitrite. This reaction is relatively inefficient and requires three equivalents of oxidant, as well as the protection of the initial Cys-SOH from nucleophilic attack. Therefore, Cys forming these PTM, particularly at biologically relevant concentrations of oxidant, are likely to be highly reactive or located in a unique microenvironment that accommodates their production without prior reduction of the Cys-SOH (e.g. by thiol or amine attack). Such sites may thus be candidates as redox or regulatory sensors (reviewed in (16)). Alternatively, over-oxidation to Cys-SO2H/SO3H during elevated oxidative stress may serve as a marker of oxidative damage, and target proteins for degradation.

Information on Cys-SO2H/SO3H PTM in complex samples has thus far been generated only by amino acid analysis (hydrolyzed lysates) (14) or two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE), where these PTM cause an acidic shift (17, 18). The former provides no information on specific proteins, whereas the latter relies on the modified population being of sufficient intensity for observation and/or the availability of antibodies against a protein-of-interest. A recent study identified 44 Cys-SO2H/SO3H-modified peptides in nonphysiologically H2O2 oxidized (440 μm) cells utilizing long column ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography (LC) (19). Global analysis of irreversible Cys-PTM thus requires enrichment that considers: (1) Cys is the second least abundant amino acid in proteins (∼1.5%) (20), and (2) Cys-SO2H/SO3H are expected to occupy only 1–2% of these Cys sites, under physiological (and perhaps even pathological) conditions.

Specific peptide enrichment by LC followed by bottom-up proteomics is a common approach used successfully for many PTMs (21, 22). Limited studies, however, have explored such techniques for Cys-SO2H/SO3H-containing peptides, and none have examined complex lysates—only single purified proteins (23, 24). Given that these PTM are among the most acidic modifications, with an average pKa of RSO2H < 2 and RSO3H ∼−3, it is pertinent to isolate these peptides by exploiting their unique charge distribution. At acidic pH, where nonmodified tryptic peptides will have an average in-solution charge state between one and two (depending on pKa of acidic residues and the C terminus), Cys-SO2H/SO3H-containing peptides will have an added negative charge, and, thus, have average charge distribution ≤ 1. Selection can therefore be performed on either positively or negatively charged resins with the former being a “positive” selection for Cys-SO2H/SO3H-containing peptides (retained by the resin), whereas the latter is a “negative” selection (Cys-SO2H/SO3H-containing peptides will not be retained by the resin). Both approaches have been used (23, 24) to capture peptides from bovine serum albumin (BSA) oxidized by performic acid – causing scission of disulfide bonds and conversion of Cys to Cys-SO3H, and methionine (Met) to the sulfone Met(O2). The studies gave comparative results, with positive selection (24) increasing Cys coverage in comparison to negative selection (23) (60% versus 45%) at the expense of specificity, with more non-Cys peptides observed in the elution.

Ultimately, any enrichment approach must be able to purify Cys-SO2H/SO3H-containing peptides from cells and tissues under physiological and/or pathological conditions, both of which will generate considerably lower levels of Cys-SO2H/SO3H than performic acid. Myocardial ischemia and reperfusion (I/R) injury is characterized by a “burst” of ROS/RNS that is observed upon reperfusion (25, 26). These ROS/RNS overwhelm the natural antioxidant defenses of the heart (27) and lead to oxidative stress that contributes to contractile dysfunction (28–30). Several studies have observed an increase in reversible Cys PTM following I/R (31–36), and an increase in Cys-SO2H/SO3H may also contribute to cellular dysfunction that ultimately leads to apoptosis and necrosis that follows prolonged I/R (myocardial infarction). Given the common practice of peptide fractionation with strong cation exchange (SCX) as a first dimension during bottom-up proteomics, we wished to explore its utility in identifying Cys-SO2H/SO3H sites in complex samples. Performic oxidized BSA and myocardial protein extracts were utilized to study the interactions occurring at each step of the method, and then the method was applied to myocardial protein extract that had been exposed to a high concentration of a less efficient oxidant (H2O2). Finally, the method was used to identify Cys-SO2H/SO3H-containing peptides derived from either physiologically relevant concentrations of H2O2 (i.e. ≤100 μm, an estimate of the likely pathological H2O2 levels (37, 38)) or from rat myocardial tissue subjected to I/R injury.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Methanol, chloroform, potassium chloride (KCl), and potassium/sodium dihydrogenphosphate (KH2PO4/NaH2PO4) were purchased from Ajax Finechem (Sydney, Australia). Sequencing grade porcine trypsin was from Promega (Madison, WI). All other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. All solutions were prepared with ultrapure Milli-Q water (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Performic Oxidation and Tryptic Digestion of BSA

Performic oxidation was performed to generate Cys-SO3H as previously described (23). Briefly, performic acid was prepared by mixing 1:19 parts H2O2 to formic acid (FA), and mixing at room temperature for 1 h. BSA (∼ 1 mg/ml) was resuspended in FA and three volumes of performic acid were added and the reaction incubated on ice for 2.5 h, before adding five volumes of Milli-Q water and evaporating to dryness. The protein was dissolved in 0.1 m NaH2PO4, pH 8, and trypsin digested for 16 h at 37 °C with a 1:25 ratio trypsin/BSA. The digest was then concentrated and desalted by solid phase extraction (SPE) on hydrophilic lipophilic balance (HLB) cartridges (Waters Corp., Milford, MA) and the eluent evaporated to dryness.

Langendorff Perfusion

All animal studies were approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee, the University of Sydney (reference: K20/4–2011/3/5517). Lewis rats (n = three per group) were euthanized with pentobarbital (200 mg kg−1), the heart rapidly excised and subjected to Langendorff perfusion for 20 min (“baseline” perfusion) with nonrecirculating Krebs buffer as previously described (39), followed by either; 1) 30 min of perfusion (nonischemic time control, NITC), or 2) 15 min of global no-flow ischemia and 15 min of reperfusion (15I/15R). Hemodynamic data based on the rate pressure product (RPP; a function of the heart rate in bpm × left ventricular developed pressure [LVdev]) expressed as a percentage of baseline showed NITC hearts were unaffected by control perfusion (RPP 105% ± 1% of baseline), whereas those subjected to 15I/15R recovered to 66% ± 5% of baseline, consistent with previous studies (7, 39). Hearts were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Myocardial Native Protein Extraction and H2O2 Oxidation

Frozen tissue (from NITC hearts) was homogenized (Omni International, Kennesaw, GA) in 0.1 m NaH2PO4, pH 7, containing 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μm aprotinin, 20 μm leupeptin, and 2 mm diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid on ice. The homogenate was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C and the supernatant removed. H2O2 was added to the supernatant to give a final concentration of 100 nm, 10 μm, 100 μm, or 10 mm and incubated at room temperature for 1 h followed by reduction with dithiothreitol (DTT) for 1 h at room temperature. Proteins then underwent chloroform/methanol precipitation to remove protease inhibitors before resuspension, trypsin digestion, and SPE cleanup, as detailed above. Peptides/proteins were quantified by Quant-iT assay (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Denaturing Protein Extraction from Myocardial Tissue

Frozen tissue was homogenized (Omni International) in 0.1 m NaH2PO4, pH 6, containing 20 mm N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), 1% (w/v) sodium dodecylsulfate, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μm aprotinin, 20 μm leupeptin, and 2 mm diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid. The homogenate was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C and the supernatant removed. Additional homogenization buffer was added to the pellet, and the pellet underwent 2 × 20 s cycles of tip-probe sonication (Branson, Darbury, CT), followed by centrifugation at 13,000 × g, 15 min, 4 °C, whereupon the supernatants were pooled. The pH was adjusted to > seven and proteins were reduced (20 mm DTT, 1 h room temperature) and free thiols reversibly modified with methylmethane thiosulfonate (40 mm in acetonitrile [MeCN]). Proteins then underwent chloroform/methanol precipitation before resuspension, trypsin digestion, and SPE cleanup, as above. Peptides or proteins were quantified by Quant-iT assay.

Performic Oxidation of Myocardial Tryptic Digest

A denatured protein extract was prepared as above with the absence of reducing and alkylating steps (i.e. no NEM in extraction buffer and no DTT reduction) to preserve disulfides. Proteins then underwent chloroform/methanol precipitation, resuspension, trypsin digestion, and SPE cleanup. The resultant peptides were performic oxidized as described for BSA, and the mixture evaporated to dryness.

Strong Cation Exchange

Peptide samples (5 μg BSA/25 μg performic oxidized extract/75 μg all other samples) were diluted in 2 ml SCX loading buffer (5 mm KH2PO4, pH 2.5) and loaded onto an SCX cartridge (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA) equilibrated with the same buffer (3 ml). The flow-through (FT) was collected and the cartridge washed with an additional 1 ml SCX loading buffer, which was pooled with the FT. The cartridge was then washed with organic wash buffer (5 mm KH2PO4, pH 2.5, 25% MeCN) and this was collected separately (fraction “MeCN”). Retained peptides were eluted (each 1 ml) with varying concentrations of 100% KCl buffer (5 mm KH2PO4, pH 2.5, 25% MeCN, and 0.5 m KCl) diluted in organic wash buffer to 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, 60, 80, and 90% KCl. All fractions containing MeCN were dried by ∼½ – ¾ to reduce the MeCN concentration and then diluted with 0.1% TFA to > 1 ml before concentration and desalting by SPE as above.

Offline Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC)

Fractionation was performed on an Agilent 1200 series capillary LC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Samples were resuspended in HILIC buffer B (90% MeCN, 0.1% triflouroacetic acid [TFA]) and separated on a home-packed column (3 μm, 20 cm × 320 μm, 100 Å pore size) of TSKgel Amide-80 beads (Tosoh Biosciences, Japan) using a gradient of 0–100% HILIC buffer A (0.1% TFA) for 29 min at a flow rate of 6 μl min−1. Between three and eight fractions were taken depending on the individual sample complexity, judged by spectrophotometric absorbance.

LC-MS/MS

Initial studies in BSA and performic oxidized extract fractionated by SCX were performed on a QSTAR Elite (ABSciex, Foster City, CA) mass spectrometer coupled online to an Agilent 1100 series nano-LC system. Follow-up studies (all SCX-HILIC fractionated samples) were acquired on either a LTQ Orbitrap Velos (Thermo Scientific, Weltham, MA) mass spectrometer coupled online to a Dionex UltiMate 3000 HPLC system (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA) or a 5600 Triple-TOF coupled online to an Eksigent nanoLC Ultra (Eksigent, Dublin, CA). Samples were resuspended in buffer A (0.1% FA) and separated on a home-packed reversed phase column (3 μm, 15 cm × 75 μm, 120 Å pore size) of ReproSil Pur C18 AQ beads (Dr. Maisch GmbH, Ammerbuch-Entringen, Germany) using the following gradients; (1) 5–40% buffer B (100% MeCN, 0.1% FA) for 105 min at 300 nL min−1 (QSTAR), (2) 0–45% buffer B2 (90% MeCN, 0.1% FA) for 50 min at 250 nL min−1 (LTQ Orbitrap Velos), or (3) 2–35% buffer B for 45 min at 300 nL min−1 (5600). All MS instruments were operated in data-dependent positive ion mode with an m/z range of 300–2000. For the QSTAR and 5600, the top five and 15 most intense precursor ions with charge states 2+ to 4+ were selected for collision-induced dissociation (CID) fragmentation, respectively. For the LTQ Orbitrap Velos, the four most intense ions with charge states 2+ to 4+ were selected for both higher energy collisional dissociation (HCD) and CID fragmentation, in an alternating manner (i.e. eight MS/MS per MS for four precursors). Dynamic exclusion was enabled with windows of 30 s (QSTAR and Orbitrap) or 10 s (5600). Raw data were scripted to .mgf in Mascot Distiller (vers. 2.4.3.3; Matrix Science, London, UK).

Data Analysis

Performic oxidized peptide data were searched against the UniProt database (BSA) or UniProt Rattus norvegicus database (taxonomy number 10116; release 2013_11) using an in-house Mascot server (vers. 2.4). Parameters were one missed cleavage, variable modifications: Met(O2), and Cys(O3), pyroglutamate (pyroGlu) at Q/E, acetyl (protein N terminus). The modification phospho (ST) was utilized for initial performic oxidized extract searches to judge levels of enrichment of contaminating phosphopeptides on HILIC. H2O2 oxidized myocardial peptide data were searched against the UniProt R. norvegicus database, as above with the addition of the variable modifications; Cys(O2), Cys(O3), Met(O), and without pyroGlu at E and phospho (ST) as these were not major contaminants in the SCX-HILIC fractions. Nonoxidized (denatured protein extract) myocardial peptide data (H2O2, NITC, and I/R samples) were searched as for H2O2-oxidized peptides with the addition of the variable modifications: NEM (C) and methylthio (C). Because the Cys-SO2H (+32 Da) and Cys-SO3H (+48 Da) modifications are of mass that could be confused with several oxidative amino acid modifications (e.g. hydroxyproline, N-formylkynurenine etc. (40)) or in a doubly modified peptide equal phosphorylation (32 + 48 = 80 Da), we searched our data including these modifications. Peptides identified with these modifications at MASCOT ion scores equal or higher than those obtained when including Cys-SO2H and SO3H were excluded from subsequent analysis. Instrument-dependent peptide/fragment tolerances of searches were; 0.2 Da/0.2 Da (QSTAR), 10 ppm/0.1 Da (Orbitrap Velos), and 50 ppm/0.1 Da (5600). Samples from H2O2-treated proteins, NITC and 15I/15R hearts were subjected to three separate SCX enrichments followed by HILIC separation. Each of the resulting FT and MeCN fractions were analyzed by LC-MS/MS as described above. All searches were performed against a decoy database and filtered to a < 2% false discovery rate (FDR). Peptides containing irreversible Cys modifications were accepted based on significant MASCOT scores. Because the numbers of peptides containing Cys-SO2H or SO3H modifications were relatively low, those identified in only a single replicate were subjected to manual annotation of their corresponding MS/MS spectra, according to the criteria as established by (41), to confirm the identification as provided by MASCOT. Reproducibility of the fractionation technique for myocardial peptides is shown in supplemental Table S4A–4F. Representative MS/MS spectra of identified Cys-SO2H and -SO3H-containing peptides from rat myocardial tissue subjected to NITC, H2O2 treatment, and 15I/15R are contained in supplemental Data S1.

Bioinformatics

Gene Ontology (GO) terms were obtained via input of UniProt identifiers into the DAVID bioinformatics tool (42) with a background reference of all GO terms from R. norvegicus. Values were obtained for fold over-representation and modified Fisher Extract calculation (43) and used to rank the results for functional clustering.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Modified SCX Strategy for the Negative Selection of Performic Oxidized Cys

A common SCX strategy is to bind peptides in a low pH aqueous mobile phase containing low salt and a percentage of organic solvent, most typically MeCN at 20–30% (v/v). The latter condition is included to limit hydrophobic retention of peptides, and, thus, increase orthogonality when coupled to reverse phase separation. A mobile phase pH of ∼2.5–3 (most commonly used) however, is within the average pKa range of Asp (3.5 ± 1.2) and the C terminus (3.3 ± 0.8) in proteins (44). It is estimated that many more peptides not containing Cys-SO2H/SO3H will be neutral at this pH than previously thought (23) – even in the absence of biological PTM (e.g. amine acetylation, protein cleavage etc.). Retention of neutral peptides by the SCX resin via hydrophobic forces would thus be advantageous to increase the negative selection of Cys-SO3H peptides from complex mixtures containing unmodified peptides with neutral charge.

SCX (pH 2.5) of performic oxidized BSA peptides in the absence of an organic modifier allowed the identification of 20 Cys-SO3H sites on 14 peptides in the “flow-through” (FT), with 67% of these peptides containing a Cys-SO3H (14/21 peptides) and the remainder constituting either nontryptic cleavages or the protein C terminus (supplemental Table S1). When 25% (v/v) MeCN was included in the mobile phase, only one additional Cys-SO3H site was identified but nine additional unmodified peptides were present, and only ∼30% peptides contained Cys-SO3H. This indicates that the initial binding of peptides in aqueous buffer to obtain the FT fraction and then performing a subsequent wash with buffer containing an organic modifier, is advantageous in depleting hydrophobic/neutral peptides from the FT. An additional nine Cys-SO3H BSA peptides were recovered in the 15% (w/v) KCl wash with 48% of peptides in this fraction containing the modification. All Cys-SO3H peptides observed here contained an additional charged residue arising from a His (nine peptides), a missed cleavage (one peptide), or an Arg/Lys followed by Pro, (R/K)-P, which is not cleaved by trypsin (four peptides). No additional sites were observed at higher concentrations of KCl. Overall, 86% of Cys sites in BSA were identified as Cys-SO3H, which is an improvement over previous methods that observed 45% (23) and 60% (24), respectively.

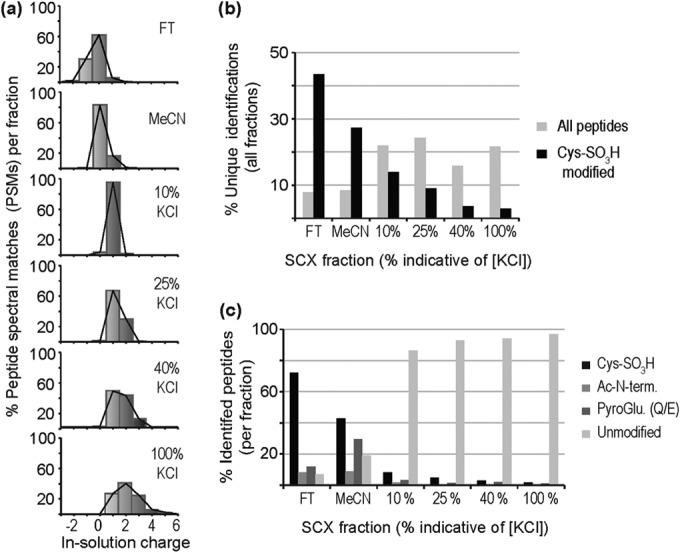

To investigate the method in a complex biological sample, we performed performic oxidation of a myocardial protein digest. Initially, an extended SCX gradient of 16 steps (supplemental Table S2) was performed to allow for the clustering of similarly charged peptides into fractions and thus avoid dilution of peptide signals (supplemental Fig. S1). It was then possible to categorize six charge distributions (Fig. 1A) and these [KCl] were used for all further SCX fractionations. The FT distribution was the only fraction skewed to the left (negatively charged) indicating electrostatic repulsion of some peptides from the resin. The organic wash (MeCN) fraction contained primarily neutral peptides, which are most likely retained by noncharge mediated interactions (i.e. dispersive). Calculations of the Kyte-Doolittle hydrophilicity (45) (estimating the hydrophilicity value of Cys-SO3H to be equivalent to Arg) showed that peptides in the FT were more hydrophilic than those in the MeCN wash (average hydrophilicity of −8.3 and −2.3, respectively). Given that both fractions appear relatively hydrophilic, we attempted to increase the elution of hydrophobic peptides by increasing the organic content to 50%; however, this did not increase the number of peptides eluting in this fraction (data not shown). All SCX elution steps (1–100% KCl) could be subdivided into four charge distributions (10%, 25%, 40, and 100%, which reflect the highest KCl concentrations demonstrating a distribution; Fig. 1A). The 1–10% (“10%”) KCl distribution contains almost entirely singly charged peptides and the higher [KCl] fractions contain increasingly positively charged peptides.

Fig. 1.

Resolution of Cys-SO3H peptides from performic oxidized myocardial extract by SCX. A, In-solution charge distributions of peptides across the six summed SCX fractions, plotted as percent of PSMs for each fraction; B, Unique peptides as a percent of total identifications occurring in all fractions, plotted for total peptides and Cys-SO3H peptides, across the six SCX fractions; C, Cys-SO3H, pyroglutamate, acetyl-modified, and unmodified peptides as a percent of total identified peptides in each fraction.

The complexity of the samples, measured as the percentage of total unique peptide identifications found in each fraction (Fig. 1B), indicated that the most complex were the salt elutions with 84% of identifications arising from these fractions. A similar plot, however, for unique Cys-SO3H identifications as a percentage of the total (Fig. 1B) indicated that the initial fractions contain 71% of the identified Cys-SO3H peptides – indicating good selection of these peptides into the relatively lower complexity FT and MeCN fractions (supplemental Table S2). Generally, we observed that the FT was more enriched in Cys-SO3H peptides (Fig. 1C), with 72% of identifications containing this modification, in comparison to the MeCN fraction with 43% of identifications. All salt fractions displayed a lower percentage of Cys-SO3H peptides, with fewer than 15% of identifications containing the modification and the majority of these (∼55%) were contained in the 10% KCl fraction. Many of the nonoxidized peptides in the FT and MeCN fractions contained PTM, such as amine acetylation (protein N terminus) and cyclization of the peptide N terminus at Glu and Gln to form pyroGlu. These PTM reduce the in-solution charge of these peptides and result in them not being retained by the resin. It could be argued that these PTM also make the peptides more hydrophobic, and this may be why a greater percentage is observed in the MeCN fraction. Because methionine can also be oxidized to methionine sulfoxide (MetOx) and methionine sulfone (MetO2), we examined the data to determine whether these Met-peptides were enriched using our approach. We observed no evidence of their enrichment in FT or MeCN fractions post-SCX, which was expected as the oxidative modification of Met does not theoretically alter charge, and thus, would not be expected to alter retention and elution from SCX chromatography. All salt fractions contained predominantly unmodified tryptic peptides.

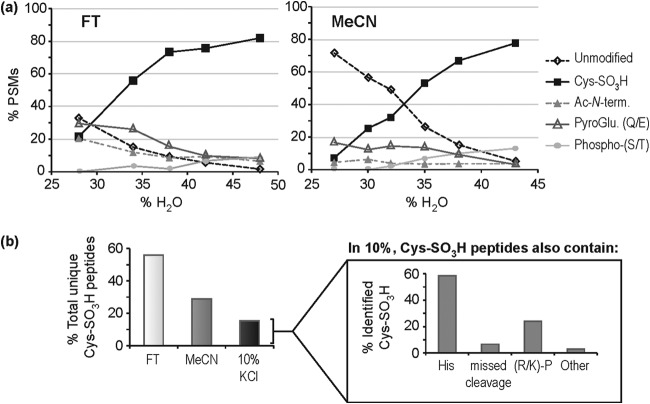

Positive Selection by HILIC Improves Cys-SO3H Peptide Identification

Given that the predominant contaminating peptides in the FT and MeCN fractions are N-terminal modifications that are expected to decrease hydrophilic interactions, we explored the use of HILIC to further enrich for Cys-SO3H-containing peptides in performic oxidized myocardial extracts (supplemental Table S3). Cys-SO3H-modified peptides fractionated by SCX (FT, MeCN) retain well on HILIC, which is denoted by increased peptide spectral matches (PSMs) to these peptides in HILIC fractions containing increased aqueous composition (Fig. 2A), whereas other peptides were relatively depleted. The possible exceptions are phosphopeptides, which are relatively sparse contaminants in early SCX fractions (<10% of PSMs in FT and MeCN), in comparison with N-terminally modified and unmodified tryptic peptides (∼20–30% of PSMs). Prior treatment of samples with phosphatases would reduce this effect; however, we chose to limit the number of sample handling steps considering the relatively minor effect phosphopeptides have on the final analysis (Fig. 2A). It was noted that the complete elution of Cys-SO3H peptides in the FT fraction required a higher percent aqueous phase than the MeCN fraction, necessitating the use of 48 and 43% H2O, respectively. This again highlights the difference in the population of these two SCX fractions; even after HILIC fractionation we only observed 15% of the total and 16% of the Cys-SO3H peptide matches as shared between SCX FT and MeCN fractions (supplemental Table S3).

Fig. 2.

HILIC separation positively selects for Cys-SO3H-containing peptides post-SCX negative selection. A, Percent total PSMs arising from unmodified/modified peptides with increasing aqueous phase; B, percentage of total Cys-SO3H peptide identifications arising from FT, MeCN, and 10% KCl fractions following HILIC enrichment. Inset shows the subdivision of peptides contained within the 10% KCl fraction by whether they are His-containing or contain a missed cleavage/(R/K)-P site.

The HILIC strategy does not aid in the further enrichment of Cys-SO3H peptides that fractionate by SCX into the salt fractions (supplemental Fig. S2A). These fractions contain many basic peptides that, like Cys-SO3H peptides, will retain well on HILIC, and are of much higher abundance in the sample. The extra dimension of chromatography, however, does increase coverage of Cys-SO3H sites in the 10% KCl fraction, which comprises ∼10% of the identified peptides. This fraction contains ∼15% of unique Cys-SO3H identifications (Fig. 2B) and this peptide population almost all contain an additional positively charged residue in their sequence. This is most commonly His (58%), but may also be the result of a missed cleavage (7%) or a (R/K)-P site (20%). Subsequent salt fractions were much less informative with <1% of unique Cys-SO3H peptides observed in these fractions combined. Given this lack of additional site information it was decided that further analysis would concentrate on FT, MeCN, and 10% KCl SCX fractions. A general schematic of the developed method is presented in Fig. 3.

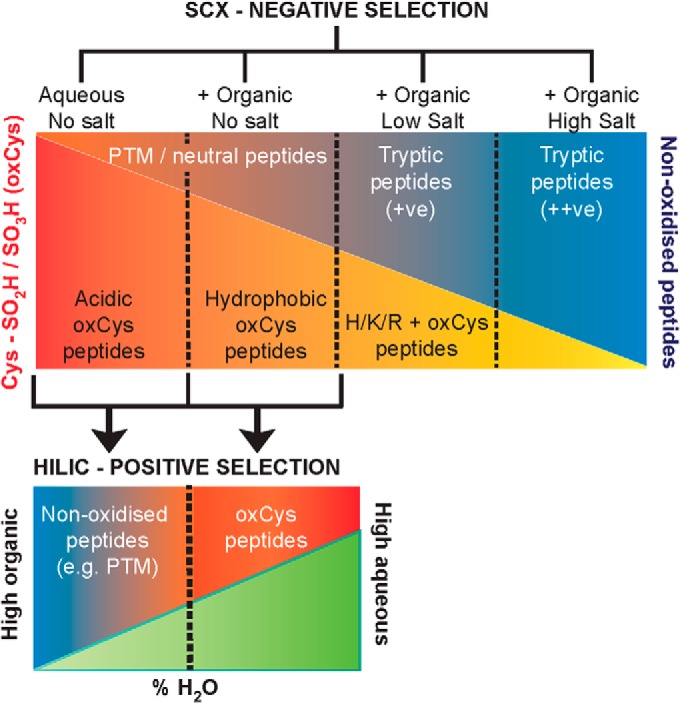

Fig. 3.

Schematic of SCX-HILIC method for the enrichment of irreversibly oxidized Cys (oxCys)-containing peptides. Initial binding of peptide samples by SCX chromatography in an aqueous buffer allows for electrostatic repulsion of peptides containing oxCys and their negative selection into the FT fraction. Subsequent washing with an aqueous phase containing an organic modifier will liberate hydrophobic and neutral oxCys peptides retained by the resin along with an increasing amount of neutral non-oxCys peptides (e.g. PTM peptides). Elution with a low salt concentration will elute retained oxCys peptides containing basic residues (H/K/R), as well as singly charged tryptic peptides, whereas increased salt concentrations will elute increasingly positive tryptic peptides. oxCys peptides from the initial fractions may be positively selected by HILIC chromatography where they are retained later than more hydrophobic PTM peptides.

Enrichment of Cys-SO2H/SO3H Modifications in H2O2 Oxidized Myocardial Extract

Performic acid is a much stronger oxidant than proteins will ever encounter biologically, resulting not only in the oxidation of thiols but also the scission of disulfides, which are otherwise relatively inert to oxidation, and, thus complete reaction to Cys-SO3H. A more common path to Cys-SO3H is sequential oxidation via Cys-SOH and Cys-SO2H, which is the pathway for oxidants such as H2O2. This is a much less efficient reaction and will thus result in the formation of fewer irreversible modifications that will include both Cys-SO2H and Cys-SO3H. Therefore, we tested the protocol with myocardial protein extracts that had been oxidized with a high concentration of H2O2 (10 mm). A native protein sample was chosen for oxidation so as to: (1) preserve any Cys reactivity designated by three-dimensional structure (e.g. Prx), which is not present once denatured; and (2) to prevent oxidation of sites that are not normally accessible to H2O2.

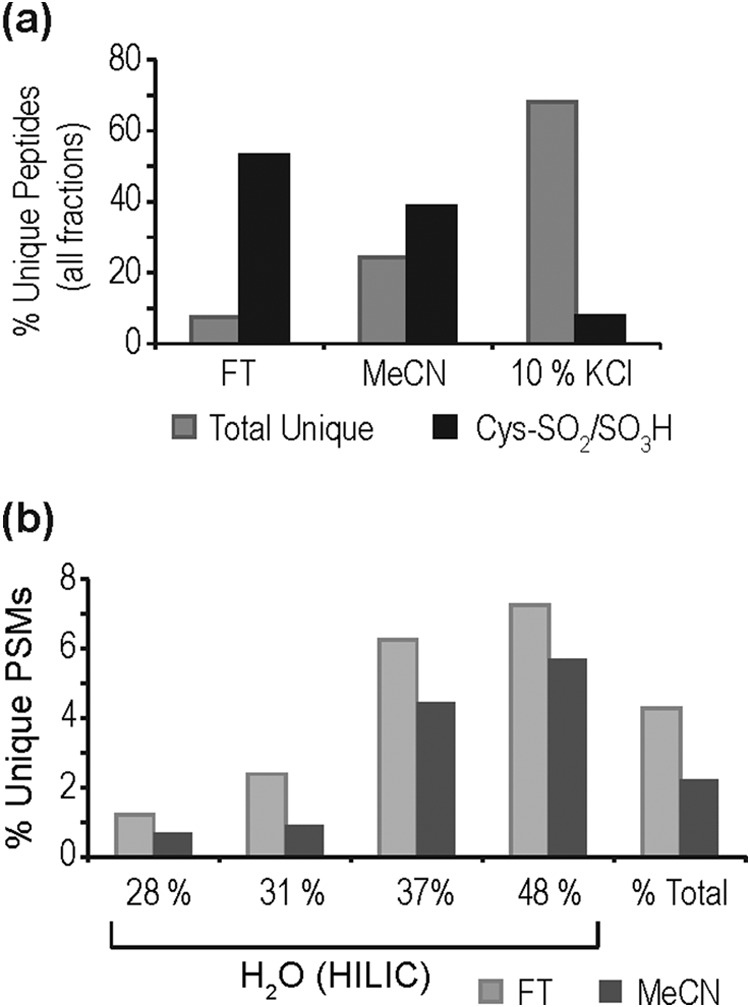

Following SCX-HILIC fractionation and LC-MS/MS (Fig. 3), we observed 119 peptides containing irreversibly oxidized Cys with 14 observed as Cys-SO2H, 76 as Cys-SO3H, and 29 in both forms (supplemental Table S4). The Cys-SO2H/SO3H peptides observed following 10 mm H2O2 oxidation fractionate similarly to the performic oxidized peptides, with 53% of unique Cys-SO2H/SO3H peptides first observed in the FT, an additional 39% observed in the MeCN fraction, and only 8% in the 10% KCl fraction (Fig. 4A), despite more extensive fractionation of the 10% KCl fraction (compared with FT and MeCN) in an attempt to increase site observation. Cys-SO2H/SO3H peptides from 10 mm H2O2-treated proteins also retain well on HILIC; however, because of their low abundance, were never a majority population, representing at most 6–8% of unique PSMs (Fig. 4B). This is not, however, a trivial level of enrichment as these PTM are estimated to be present at <2% of Cys residues (14), whereas N-terminal acetylation for example occurs at many, if not most, protein N termini. Again, the largest contaminants were these acetylated protein N termini, as well as N-terminal pyroGlu and unmodified tryptic or nontryptic peptides (e.g. protein C termini). It is worth noting that with the increased total peptide loading that is necessary to observe Cys-SO2H/SO3H in 10 mm H2O2-treated samples (which is still less than the binding capacity of the resin), decreased retention of acidic peptides was observed, particularly in the MeCN fraction, with 51% of unmodified peptides containing two or more acidic residues in their sequence. Reduction of loading and wash volumes, to prevent increased hydrophilic partitioning at higher loads, did not reduce this effect (data not shown). It would therefore be best to utilize a column with a much higher loading capacity (>100 μg) as it would likely reduce this effect and allow for the increased observation of low abundance sites.

Fig. 4.

Fractionation of peptides generated from myocardial extract oxidized by 10 mm H2O2. A, Percent total unique and unique Cys-SO2H/SO3H peptides identified in each fraction; B, PSMs corresponding to Cys-SO2H/SO3H peptides enriched with increased aqueous phase by HILIC, with the percent total representing the average over all fractions.

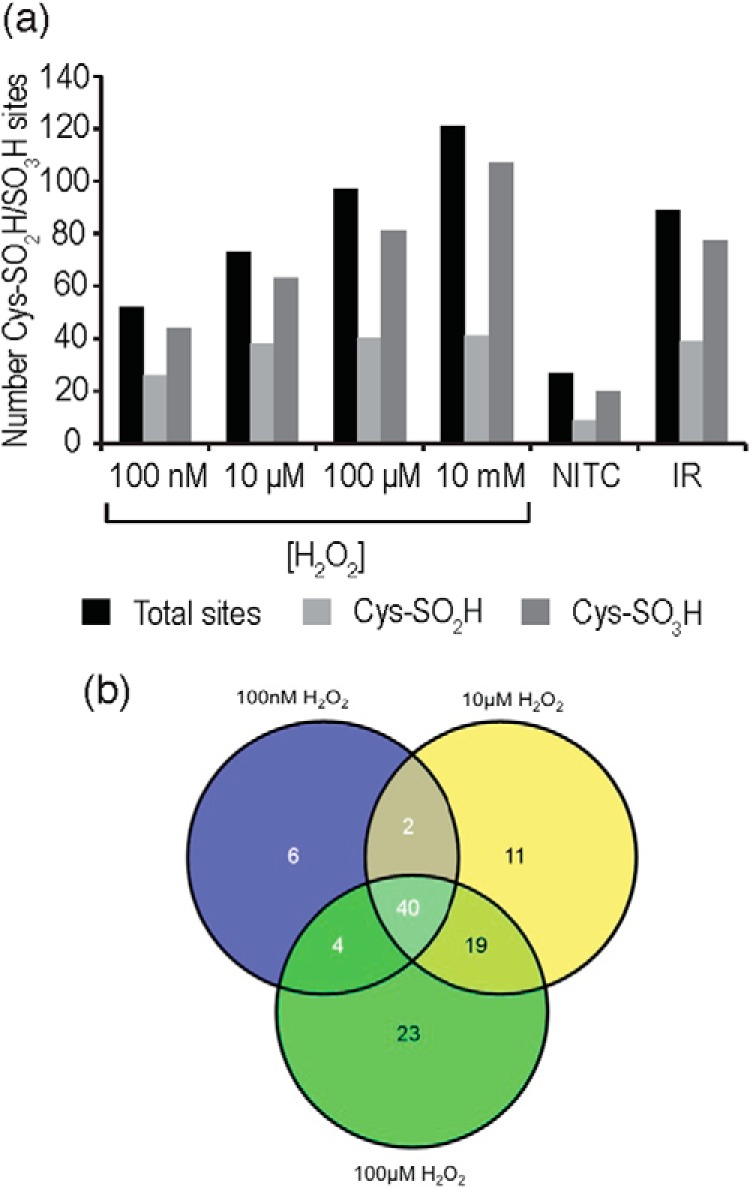

The biological range for H2O2 concentration ([H2O2]) is a point of considerable conjecture, but the general range of physiologically relevant concentrations is thought to be 1–700 nm (37) with an upper limit of 1–15 μm measured in some tissues (38), whereas the pathological concentrations are not thought to exceed 200 μm (38). Thus, measurements made above these levels are unlikely to be directly physiologically relevant and may result in the oxidation of relatively unreactive sites. To better reflect the physiological and pathological range of H2O2 concentrations, isolation of irreversibly oxidized Cys-containing peptides was undertaken from rat myocardial proteins exposed to 100 nm, 10 μm, and 100 μm H2O2. At 100 nm, 52 sites were observed (Fig. 5A and supplemental Table S4) with nine Cys-SO2H, 27 Cys-SO3H and 16 Cys-SO2H/SO3H sites. At higher [H2O2] this increased, with 72 observed at 10 μm H2O2 (10 Cys-SO2H, 35 Cys-SO3H, and 27 Cys-SO2H/SO3H) and 86 sites at 100 μm H2O2 (14 Cys-SO2H, 49 Cys-SO3H, and 23 Cys-SO2H/SO3H). In total, 105 sites were observed across all H2O2 concentrations, with a large number (40 sites) observed across all three (Fig. 5B and supplemental Table S4). Many unique sites were also observed in lysates exposed to 100 μm H2O2 alone, or were shared between the 10 μm and 100 μm concentrations.

Fig. 5.

Cys-SO2H/SO3H-containing peptide identifications in myocardial extracts oxidized by differing [H2O2] and in myocardial tissue subjected to Langendorff perfusion (NITC and I/R). A, Number of sites observed in each sample, with total sites, Cys-SO2H and Cys-SO3H sites denoted; B, overlap of Cys-SO2H/SO3H sites identified at 100 nm, 10 μm, and 100 μm H2O2.

By increasing prefractionation steps we were able to observe an increase in coverage of the irreversible Cys proteome even when measuring sites produced at [H2O2] less than a quarter of those applied in other studies (19). The main reason for advocating a method with no prefractionation would be to decrease artifacts, but as all chromatography techniques are performed at acidic pH (<3) and on peptides, artifact generation is much more likely to occur during extraction and digestion than prefractionation. To couple this method to site determination in tissues that are not treated with exogenous oxidants, care should be taken to avoid formation of artifacts by performing extractions at low pH, in solutions containing strong denaturants (e.g. detergents), low pH alkylating agents (46), and metal ion chelators. Protease inhibition is of high importance, as the method is particularly sensitive to nontryptic proteolysis occurring at any stage in the protocol. Conversely, the method will also be sensitive to incomplete tryptic cleavage, which will increase the percentage of Cys-SO2H/SO3H sites eluting in the SCX salt fractions. To ensure low levels of missed tryptic cleavages, increased trypsin/protein ratios can be utilized for digestion. Unfortunately, increasing pH, reaction time and temperature of digestion will also lead to increased formation of pyroGlu at N termini. Any increased contamination of the FT/MeCN fractions by pyroGlu peptides should be endured as the chance of resolving correctly cleaved Cys-SO2H/SO3H from pyroGlu in these fractions by HILIC is much higher than resolving missed cleaved Cys-SO2H/SO3H peptides from unmodified tryptic peptides in SCX salt fractions.

Enrichment of Cys-SO2H/SO3H Modifications Following Myocardial I/R Injury

Protein extracts/cells treated with exogenous oxidants remain a questionable model of pathology. Thus, we sought to decipher whether the method could be applied to myocardial tissue subjected to pathologically relevant I/R injury via Langendorff perfusion. I/R injury is associated with acute oxidative stress, particularly during early reperfusion, and which is thought to generate oxidative protein damage leading to contractile dysfunction and eventually apoptosis and necrosis. We performed enrichment of Cys-SO2H/SO3H-containing peptides from rat myocardium subjected to either 30 min of control perfusion (“nonischemic time control”; NITC) or 15 min no-flow ischemia with 15 min reperfusion (15I/15R; I/R). From the NITC extract we observed 24 sites; five Cys-SO2H, 17 Cys-SO3H and two Cys-SO2H/SO3H sites (Fig. 5A and supplemental Table S4). Following I/R, the number of observed sites increased >threefold (84 sites; eight Cys-SO2H, 49 Cys-SO3H, and 27 Cys-SO2H/SO3H sites). Of the 24 sites identified in NITC samples, 15 were identified in the samples subjected to I/R. Although we did not perform quantitative analysis (label-based), several of these peptides were observed in I/R in both the SO2H and SO3H forms, potentially indicating a larger proportion of the protein pool is irreversibly oxidized. Additionally, we examined identifications from the FT, MeCN, and KCl fractions to determine whether the increase in irreversibly oxidized Cys-peptides in 15I/15R was also reflected in a change in the ratio of unmodified/reversibly modified Cys-peptides between NITC and 15I/15R. Our sample preparation protocol uses NEM to alkylate unmodified Cys thiols and then subsequent DTT/MMTS treatment to reduce and alkylate Cys peptides containing Cys in a reversibly modified form. We interrogated the data to examine peptides containing Cys-NEM modification (unmodified Cys-peptides) and Cys-methylthio modification (reversibly modified Cys-peptides). In NITC hearts, 128 (26.1% of all identified Cys-peptides) Cys-containing peptides were reversibly modified and 339 (69.0%) were unmodified, whereas following 15I/15R we identified 243 (38.0%) reversibly modified Cys-peptides and 313 (48.9%) that were unmodified (data not shown), which is consistent with the more oxidizing environment during I/R injury. It was noted that many of the sites observed as irreversibly oxidized following I/R were also observed in H2O2-treated extracts (62% overlap; Table I), indicating that these may be pathologically relevant, and site identification numbers were very similar to those observed for the 100 μm H2O2 sample (Fig. 5A). In NITC tissue, the overlap to H2O2-treated extracts was 42%, with the unique peptides largely representing myofilament/cytoskeletal proteins, which were not observed in H2O2 treated samples, most likely because of their low solubility in aqueous solutions without denaturants.

Table I. Summary of Cys-SO2H/SO3H peptides observed in Langendorff perfused myocardial tissue (NITC, I/R) compared with H2O2-treated myocardial samples. Proteins that contain Cys-SO2H/SO3H PTM were clustered by biological function. Sites were observed as shown, with the numbers indicating observation of: “2” sulfinic acid, “3” sulfonic acid, “2,3” both forms independently, “(2/3)” both forms on the same peptide (doubly modified peptide). ** Indicates the site was observed in the 10 mm H2O2 concentration only. All identifications are provided in supplementary Table S4.

| Protein Identifier | Protein Description | Peptide Sequence | Cys-SOnH (n = 2 or 3) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NITC | I/R | H2O2 | |||

| GLYCOLYSIS/GLUCOSE METABOLISM | |||||

| ALDOA_RAT | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A | ALANSLACQGK | 2,3 | 2,3 | |

| TPIS_RAT | Triosephosphate isomerase | CLGELICTLNAAK | 3 | 3 | 2,3 |

| IAVAAQNCYK | 3 | 3 | |||

| IIYGGSVTGATCK | 3 | ||||

| G3P_RAT | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | VPTPNVSVVDLTCR | 3 | 2,3 | 2,3 |

| F1M3E5_RAT | Uncharacterized protein (Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase family) | IVSNASGITNCLAPLAK | 2 | 2,3 | 2 |

| M0R4Q0_RAT | Uncharacterized protein (Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase family) | IIVSNASCTTNCLAPLAK | 3 | 2,3 | |

| ENOB_RAT | Beta enolase | VNQIGSVTESIQACK | 2,3 | 2,3 | |

| D4ADU8_RAT | Pyruvate kinase | KLHATCAEGIDVAK | 2 | 2 | |

| KPYM_RAT | Pyruvate kinase PKM | AEGSDVANAVLDGADCIMLSGETAK | 3 | 3 | |

| LDHA_RAT | l-Lactate dehydrogenase A chain | VIGSGCNLDSAR | 2,3 | 2,3 | |

| CITRIC ACID CYCLE | |||||

| ODPB_RAT | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit beta | EGIECEVINLR | 3 | 3 | |

| CISY_RAT | Citrate synthase, mitochondrial | LPCVAAK | 2,3 | 2,3 | |

| ACON_RAT | Aconitate hydratase, mitochondrial | VGLIGSCTNSSYEDMGR | 3 | 2,3 | 2,3 |

| IDHP_RAT | Isocitrate dehydrogenase [NADP], mitochondrial | CATITPDEAR | 2,3 | 2,3 | |

| VCVQTVESGAMTK | 2,3 | 2,3 | |||

| DHSA_RAT | Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein subunit | VGSVLQEGCEK | 3 | 3 | |

| MDHC_RAT | Malate dehydrogenase, cytoplasmic | ENFSCLTR | 3 | 3 | |

| VIVVGNPANTNCLTASK | 2,3 | 2,3 | |||

| MDHM_RAT | Malate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | EGVIECSFVQSK | 3 | 2,3 | 2,3 |

| ETECTYFSTPLLLGK | 2,3 | 2,3 | |||

| GCDVVVIPAGVPR | 2,3 | 2,3 | |||

| GYLGPEQLPDCLK | 3 | 2,3 | |||

| ELECTRON TRANSPORT/ATP SYNTHESIS | |||||

| ATP5H_RAT | ATP synthase subunit d, mitochondrial | NCAQFVTGSQAR | 2,3 | 2,3 | |

| ATP5E_RAT | ATP synthase subunit epsilon, mitochondrial | FSQICAK | 3 | ||

| ETFA_RAT | Electron transfer flavoprotein subunit alpha, mitochondrial | LGGEVSCLVAGTK | 3 | 2,3 | |

| QCR1_RAT | Cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 1, mitochondrial | LCTSATESEVTR | 3 | 2,3 | 2,3 |

| YFYDQCPAVAGYGPIEQLSDYNR | 2,3** | ||||

| QCR2_RAT | Cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 2, mitochondrial | NALANPLYCPDYR | 3 | 2,3 | |

| COX5B_RAT | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 5B, mitochondrial | CPNCGTHYK | 3 | ||

| B2RYW3_RAT | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 beta subcomplex 9 | AFCAPPAYLTHR | 3 | 3 | |

| NDUS1_RAT | NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase 75 kDa subunit | AVTEGAQAVEEPSIC | 3 | ||

| FATTY ACID/AMINO ACID METABOLISM | |||||

| ACADS_RAT | Short-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | IGCFALSEPGNGSDAGAASTTAR | 3 | 3 | 3** |

| IGIASQALGIAQASLDCAVK | 3 | ||||

| ACADV_RAT | Very long-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | SSAVPSPCGK | 2,3 | 2,3 | |

| ACADL_RAT | Long-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | CIGAIAMTEPGAGSDLQGVR | 2,3 | 2,3 | |

| ACADM_RAT | Medium-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | MTEQPMMCAYCVTEPSAGSDVAGIK | 2,3 | ||

| ECHM_RAT | Enoyl-CoA hydratase, mitochondrial | TFQDCYSGK | 3 | 3 | |

| THIL_RAT | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, mitochondrial | QATLGAGLPIATPCTTVNK | 3 | 3 | |

| MCAT_RAT | Carnitine/acylcarnitine carrier protein | CLLQIQASSGK | 3 | ||

| AATC_RAT | Aspartate aminotransferase, cytoplasmic | SCASQLVLGDNSPALR | 2,3 | 2,3 | |

| AATM_RAT | Aspartate aminotransferase, mitochondrial | TCGFDFSGALEDISK | 3 | 2,3 | 2,3 |

| VGAFTVVCK | 3 | 3 | |||

| MMSA_RAT | Methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | CMALSTAVLVGEAK | 2 | 2,3 | 2,3 |

| VCNLIDSGAK | 3 | 2,3** | |||

| DCMC_RAT | Malonyl-CoA decarboxylase, mitochondrial | TPAPAEGQCADFVSFYGGLAEAAQR | 3 | ||

| ALDH2_RAT | Aldehyde dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | LLCGGGAAADR | 3 | 2 | |

| FABP4_RAT | Fatty acid-binding protein | CDAFVGTWK | 3 | 2,3 | |

| MYOFILAMENT/CYTOSKELETON | |||||

| ACTC_RAT | Actin, alpha cardiac muscle 1 | CDDEETTALVCDNGSGLVK | 2,3 | 2 | |

| ACTA_RAT | Actin, aortic smooth muscle | MCEEEDSTALVCDNGSGLCK | (2/3) | ||

| ACTB_RAT | Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | DDDIAALVVDNGSGMCK | 3 | ||

| LLCYVALDFEQEMATAASSSSLEK | 2,3 | ||||

| ACTG_RAT | Actin, cytoplasmic 2 | EEEIAALVIDNGSGMCK | 3 | 3 | |

| MEEEIAALVIDNGSGMCKAGFAGDDAPR | |||||

| ACTH_RAT | Actin, gamma enteric smooth muscle | CEEETTALVCDNGSGLCKAGFAGDDAPR | 2 | ||

| MCEEETTALVCDNGSGLCKAGFAGDDAPR | (2/2) | ||||

| CAPZB_RAT | F-actin capping protein subunit beta | MSDQQLDCALDLMR | 3 | ||

| MYL3_RAT | Myosin light chain 3 | ITYGQCGDVLR | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| LMAGQEDSNGCINYEAFVK | 3 | ||||

| MYH10_RAT | Myosin 10 | KDQSILCTGESGAGK | 3 | 3 | |

| MYH6_RAT | Myosin 6 | CIIPNER | 2 | 3 | |

| CNGVLEGIR | 2 | ||||

| MYPC_RAT | Myosin-binding protein C, cardiac-type | DQAVFKCEVSDENVR | 3 | ||

| MYO1E_RAT | Unconventional myosin Ie | ENQCVIISGESGAGK | 3 | ||

| TPM1_RAT | Tropomyosin alpha-1 chain | CAELEEELK | 2,3 | ||

| VIME_RAT | Vimentin | QVQSLTCEVDALK | 3 | ||

| ION TRANSPORT | |||||

| IRK11_RAT | ATP sensitive inward rectifier potassium channel 11 | LCFMLR | 3 | ||

| ADT1_RAT | ADP/ATP translocase 1 | EFNGLGDCLTK | 2,3 | 2,3 | |

| GADIMYTGTVDCWR | 3 | 2**,3 | |||

| ADT2_RAT | ADP/ATP translocase 2 | YFAGNLASGGAAGATSLCFVYPLDFAR | 3 | ||

| AT2A2_RAT | Sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 | VGEATETALTCLVEK | 3 | 2**,3 | |

| AT2A3_RAT | Sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 3 | CGQFDGLVELATICALCNDSALDYNEAK | 3 | ||

| MPCP_RAT | Phosphate carrier protein, mitochondrial | GWAPTLIGYSMQGLCK | 3 | 3 | |

| RESPONSE TO STRESS/HYPOXIA/ROS | |||||

| HSPB8_RAT | Heat shock protein beta 8 | ADGQLPFPCSYPSR | 3 | ||

| CH60_RAT | 60 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial | AAVEEGIVLGGGCALLR | 3 | 3 | |

| PRDX5_RAT | Peroxiredoxin 5, mitochondrial | GVLFGVPGAFTPGCSK | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| PRDX6_RAT | Peroxiredoxin 6 | DFTPVCTTELGR | 3 | 3 | 2,3 |

| D4ADD7_RAT | Glutaredoxin 5 homolog (Predicted), isoform CRA | GTPEQPQCGFSNAVVQILR | 3 | 2**,3 | |

| VARIOUS FUNCTIONS/FUNCTION UNKNOWN | |||||

| RS28_RAT | 40S ribosomal protein S28 | TGSQGQCTQVR | 3 | ||

| KCRM_RAT | Creatine kinase M-type | FCVGLQK | 3 | 3 | |

| KCRS_RAT | Creatine kinase S-type, mitochondrial | LGYILTCPSNLGTGLR | 2,3 | 2,3 | |

| CFAI_RAT | Complement factor I | SGVCIPNQR | 3 | 3 | |

| ES1_RAT | ES1 protein homolog, mitochondrial | KPIGLCCIAPVLAAK | 3 | 3 | |

| MUC2_RAT | Mucin 2 | GRCVPLSK | 2 | 2 | |

| HBB1_RAT | Hemoglobin subunit beta 1 | EFTPCAQAAFQK | 3 | 3 | 2,3 |

| D3ZA85_RAT | Histone cell cycle regulation defective interacting protein 5 | LQGSCTSCPSSIITLK | 3 | ||

| G3V8S8_RAT | Oxysterol-binding protein | DGFCMSGSITAK | 3 | ||

| NHRF2_RAT | Na+/H+ exchange regulatory cofactor NHE-RF2 | QLTCTEEMAHR | 2,3 | 3 | |

| D3ZQW1_RAT | Protein Blm | CSSMLKDLDDSDK | 2 | ||

| E9PT83_RAT | Protein Cenpf | LECMLSECTALCENK | (2/3) | ||

| D3ZSE6_RAT | Protein Dfnb59 | RETVYGCFQCSVDGVK | 3 | ||

| E9PU13_RAT | Protein Snx4 | EYLFYAEALRAVCR | 2 | ||

| F1LU05_RAT | Uncharacterized protein | SYEQQCIEELR | 2 | ||

Irreversible protein oxidation, particularly of myofilament proteins, has been suggested as a potential cause of decreased myocardial contractility following I/R (33, 35, 47, 48). The myofilament or cytoskeleton does appear to be a site of irreversible Cys oxidation, with seven Cys-SO2H/SO3H sites contained on six myofilament/cytoskeletal proteins in NITC samples, and increasing to 17 sites on 12 proteins following I/R (Table I and supplemental Table S4). When functional clustering was performed (supplemental Fig. S3), several other clusters were also observed as over-represented. The most over-represented cluster contains mitochondrial proteins, likely because of both the role of mitochondria in oxidant generation and also their high abundance in myocardial tissue. The second over-represented cluster were oxidoreductases, as their role in electron transport likely makes them susceptible to oxidation, particularly those proteins containing metal centers or those involved in the detoxification of oxidants (e.g. Prx). Further sub-clustering indicates energy utilization pathways are over-represented (Table I), including proteins involved in glycolysis (6/9 enzymes), the citrate cycle (6/7 enzymes), electron transport chain (ETC)/ATP synthase (nine proteins), and fatty acid/amino acid metabolism (13 proteins). Interestingly, we observed their Cys oxidation state across NITC and I/R to be quite distinct. Although glycolytic enzymes contain Cys-SO2H/SO3H modifications even in NITC tissue, citrate cycle enzymes, and electron transport/ATP synthase enzymes were almost only ever observed to contain Cys-SO2H/SO3H modifications following I/R (or H2O2 treatment). This may be because of their differing subcellular localization, that is, cytoplasmic versus mitochondrial, but a similar trend was not observed for proteins involved in fatty acid or amino acid metabolism, many of which are also located in the mitochondria and are still observed as oxidized in NITC tissue.

Over all the conditions studied (NITC, I/R, and H2O2 treatment), 181 Cys-SO2H/SO3H sites were observed, which constitutes the largest number of irreversibly modified Cys sites currently revealed in the literature. Interestingly, ∼30–50% of total site identifications under each condition contained Cys-SO2H, whereas substantially more (70–80%) could be monitored in the Cys-SO3H form (Fig. 5A). This may be because: (1) Cys-SO2H is more efficiently oxidized to Cys-SO3H than Cys-SOH is to Cys-SO2H; or (2) Cys-SO3H gives better spectral characteristics for assignment. The observation that the Cys-SO2H peptide percentage of total Cys-SO2H/SO3H identifications negatively correlated with [H2O2] may indicate that the former is a possibility (with I/R sitting in between 10 and 100 μm H2O2 samples). Although, as the NITC samples had the lowest Cys-SO2H % of total Cys-SO2H/SO3H identifications (similar to 10 mm H2O2) this may indicate that spectral assignment at low intensities may be better for Cys-SO3H.

Our technique is, however, likely to be poorly compatible with iTRAQ/tandem mass tags (TMT) as these add an extra charge for every N terminus and Lys modified. This essentially shifts all peptide in-solution charge states up by two for every peptide ending with Lys, and one for those ending in Arg. It is this factor (Lys versus Arg peptide charge) that causes co-elution of Arg peptides with some containing Cys-SO2H/SO3H (those ending in Lys or containing His), which will have the same in-solution charge but are of vastly lower abundance. Thus, quantitative analysis of these modifications is likely to be most successful by independent sample analysis using label-free quantitation (e.g. spectral counting), MS precursor area, or for those compatible cell and tissue types, label-based quantitation that does not alter the charge or hydrophilicity of peptides (e.g. stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture [SILAC]). Additionally, the observation of Cys-SO2H/SO3H peptides is made much harder by their extremely low abundance and hence site stoichiometry of reduced/reversibly oxidized/irreversibly oxidized forms may only be possible via techniques such as oxMRM (49), which specifically target a small subset of sites for label-free quantitation, but requires prior knowledge of the modified sites. Recent work has tried to eliminate some of these problems for nonmodified/reversibly modified redox sites by employing cysTMTRAQ (50) to determine changes in redox-modified peptide abundance with respect to protein turnover.

To our knowledge, this is also the only proteomics study to enrich Cys-SO2H/SO3H-containing peptides from tissue, which had not been subjected to exogenous oxidant addition. The sites observed agree well with sites that are known to be reversibly Cys modified under various conditions (7), indicating that multiple PTMs occur at these Cys sites, including both reversible and irreversible forms. Comparing the sites we observed with a database of annotated sites (RedoxDB (51)) from composite studies across multiple organisms, we observed that 40% of the Cys-SO2H/SO3H sites occur at previously identified reversibly modified Cys, and an additional 12% occur on proteins that have previously been identified as redox modified at unknown sites (supplemental Table S4). Extending this analysis to include our recent study of reversibly modified Cys in the myocardium (7), we see that only 20% of Cys-SO2H/SO3H modifications are located at sites that are completely novel redox sites, i.e. not already known to be occupied by a reversible Cys PTM (supplemental Table S4).

CONCLUSION

Cys-SO2H/SO3H sites are of particular interest as they likely represent Cys residues with high reactivity or unique microenvironments facilitating Cys-SOH stabilization and reaction to higher oxidation states. We exploited the unique characteristics of tryptic peptides containing Cys-SO2H/SO3H to generate a novel method based on sequential: (1) negative selection by electrostatic repulsion using SCX (which separates them from the bulk of tryptic peptides); and then (2) positive selection by hydrophilic interactions using HILIC (which increases separation from other PTM-containing peptides in the SCX FT and MeCN fractions). Increased fractionation allows for the observation of a greater number of sites, whereas also allowing for increases in starting material. This improves the quality of MS data/spectral assignments and potentially aids in the identification of low abundance sites. Utilizing this strategy, we observed 181 Cys-SO2H/SO3H sites in myocardial tissue extracts, which were treated with physiological to pathological levels of H2O2, or were generated by biologically relevant ex vivo Langendorff perfusion. The majority of Cys-SO2H/SO3H residues were located at sites previously identified as modified by reversible Cys modifications, increasing the diversity of Cys PTM at these sites. Furthermore, we showed that even brief I/R injury induces significant over-oxidation of myocardial proteins, which is consistent with the oxidative damage assumed to occur during I/R. Oxidative protein damage of many targets may be a significant contributor to contractile dysfunction and potentially a major factor in pathways leading to myocyte apoptosis and necrosis. This technique is widely applicable to various sample types and biological treatments, allowing for the discovery of targets of Cys-SO2H/SO3H PTM induced by exposure to ROS/RNS.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Author contributions: J.P. and S.J.C. designed research; J.P., K.A.L., K.E., and M.Y.W. performed research; J.P., M.Y.W., and S.J.C. analyzed data; J.P. and S.J.C. wrote the paper.

* This work was supported in part by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC; 571002 to S.J.C.) of Australia and the NSW State Government (NSW-China Collaborative Research Project (S.J.C. and M.Y.W.)). J.P. and K.A.L. are recipients of Australian Postgraduate Awards (APA). M.Y.W. is an Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Early Career Research Award (DECRA) Fellow. K.E.-K. is supported by the Lundbeck Foundation (Postdoctoral Fellowship), The Danish Council for Independent Research and the European Union FP7 Marie Curie Actions – COFUND program (MOBILEX Postdoctoral Fellowship DFF-1325-00154). LTQ Orbitrap Velos and 5600 Triple TOF instrument data were acquired at the Biomedical Proteomics and Australian Cancer Research Foundation (ACRF) Centre for Kinomics, Children's Medical Research Institute, Westmead, NSW 2145, Australia. We thank Dr. Valentina Valova for instrument access and assistance.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 to S3, Data S1, and Tables S1 to S4.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 to S3, Data S1, and Tables S1 to S4.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- Cys

- cysteine

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- Cys-SOH

- sulfenic acid

- Cys-SO2H

- sulfinic acid

- Cys-SO3H

- sulfonic acid

- DTT

- dithiothreitol

- FA

- formic acid

- FDR

- false discovery rate

- FT

- flowthrough

- GO

- gene ontology

- HILIC

- hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography

- I/R

- ischemia/reperfusion

- LC-MS/MS

- liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- NEM

- N-ethylmaleimide

- NITC

- nonischemic time control

- Prx

- peroxiredoxin

- PSM

- peptide spectral match

- PTM

- post-translational modification

- RNS

- reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- SPE

- solid phase extraction

- Srx

- sulfiredoxin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dröge W. (2002) Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 82, 47–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Valko M., Leibfritz D., Moncol J., Cronin M. T. D., Mazur M., Telser J. (2007) Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39, 44–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gygi S. P., Rist B., Gerber S. A., Turecek F., Gelb M. H., Aebersold R. (1999) Quantitative analysis of complex protein mixtures using isotope-coded affinity tags. Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 994–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hägglund P., Bunkenborg J., Maeda K., Svensson B. (2008) Identification of thioredoxin disulfide targets using a quantitative proteomics approach based on isotope-coded affinity tags. J. Proteome Res. 7, 5270–5276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sethuraman M., McComb M. E., Heibeck T., Costello C. E., Cohen R. A. (2004) Isotope-coded affinity tag approach to identify and quantify oxidant-sensitive protein thiols. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 3, 273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sethuraman M., McComb M. E., Huang H., Huang S., Heibeck T., Costello C. E., Cohen R. A. (2004) Isotope-coded affinity tag (ICAT) approach to redox proteomics: identification and quantitation of oxidant-sensitive cysteine thiols in complex protein mixtures. J. Proteome Res. 3, 1228–1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paulech J., Solis N., Edwards A. V., Puckeridge M., White M. Y., Cordwell S. J. (2013) Large-scale capture of peptides containing reversibly oxidized cysteines by thiol-disulfide exchange applied to the myocardial redox proteome. Anal. Chem. 85, 3774–3780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu T., Qian W. J., Camp D. G., 2nd, Smith R. D. (2007) The use of a quantitative cysteinyl-peptide enrichment technology for high-throughput quantitative proteomics. Methods Mol. Biol. 359, 107–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu T., Qian W. J., Strittmatter E. F., Camp D. G., Anderson G. A., Thrall B. D., Smith R. D. (2004) High-throughput comparative proteome analysis using a quantitative cysteinyl-peptide enrichment technology. Anal. Chem. 76, 5345–5353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guo J., Gaffrey M. J., Su D., Liu T., Camp D. G., 2nd, Smith R. D., Qian W. J. (2014) Resin-assisted enrichment of thiols as a general strategy for proteomic profiling of cysteine-based reversible modifications. Nat. Protoc. 9, 64–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Doulias P. T., Greene J. L., Greco T. M., Tenopoulou M., Seeholzer S. H., Dunbrack R. L., Ischiropoulos H. (2010) Structural profiling of endogenous S-nitrosocysteine residues reveals unique features that accommodate diverse mechanisms for protein S-nitrosylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 16958–16963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Doulias P. T., Tenopoulou M., Greene J. L., Raju K., Ischiropoulos H. (2013) Nitric oxide regulates mitochondrial fatty acid metabolism through reversible protein S-nitrosylation. Sci. Signal. 6, rs1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Biteau B., Labarre J., Toledano M. B. (2003) ATP-dependent reduction of cysteine-sulphinic acid by S. cerevisiae sulphiredoxin. Nature 425, 980–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hamann M., Zhang T., Hendrich S., Thomas J. A. (2002) Quantitation of protein sulfinic and sulfonic acid, irreversibly oxidized protein cysteine sites in cellular proteins. Methods Enzymol. 348, 146–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blackinton J., Lakshminarasimhan M., Thomas K. J., Ahmad R., Greggio E., Raza A. S., Cookson M. R., Wilson M. A. (2009) Formation of a stabilized cysteine sulfinic acid is critical for the mitochondrial function of the parkinsonism protein DJ-1. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6476–6485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lo Conte M., Carroll K. S. (2013) The redox biochemistry of protein sulfenylation and sulfinylation. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 26480–26488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wagner E., Luche S., Penna L., Chevallet M., Van Dorsselaer A., Leize-Wagner E., Rabilloud T. (2002) A method for detection of overoxidation of cysteines: peroxiredoxins are oxidized in vivo at the active-site cysteine during oxidative stress. Biochem. J. 366, 777–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jeong J., Jung Y., Na S., Lee E., Kim M. S., Choi S., Shin D. H., Paek E., Lee H. Y., Lee K. J. (2011) Novel oxidative modifications in redox-active cysteine residues. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 10, M110.000513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee C. F., Paull T. T., Person M. D. (2013) Proteome-wide detection and quantitative analysis of irreversible cysteine oxidation using long column UPLC-pSRM. J. Proteome Res. 12, 4302–4315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pe'er I., Felder C. E., Man O., Silman I., Sussman J. L., Beckmann J. S. (2004) Proteomic signatures: amino acid and oligopeptide compositions differentiate between phyla. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 54, 20–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beausoleil S. A., Jedrychowski M., Schwartz D., Elias J. E., Villén J., Li J., Cohn M. A., Cantley L. C., Gygi S. P. (2004) Large-scale characterization of HeLa cell nuclear phosphoproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12130–12135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Larsen M. R., Thingholm T. E., Jensen O. N., Roepstorff P., Jørgensen T. J. D. (2005) Highly selective enrichment of phosphorylated peptides from peptide mixtures using titanium dioxide microcolumns. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 4, 873–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dai J., Wang J., Zhang Y., Lu Z., Yang B., Li X., Cai Y., Qian X. (2005) Enrichment and identification of cysteine-containing peptides from tryptic digests of performic oxidized proteins by strong cation exchange LC and MALDI-TOF/TOF MS. Anal. Chem. 77, 7594–7604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chang Y. C., Huang C. N., Lin C. H., Chang H. C., Wu C. C. (2010) Mapping protein cysteine sulfonic acid modifications with specific enrichment and mass spectrometry: an integrated approach to explore the cysteine oxidation. Proteomics 10, 2961–2971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bolli R., Patel B. S., Jeroudi M. O., Lai E. K., McCay P. B. (1988) Demonstration of free radical generation in “stunned” myocardium of intact dogs with the use of the spin trap alpha-phenyl N-tert-butyl nitrone. J. Clin. Invest. 82, 476–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bolli R. (1988) Oxygen-derived free radicals and postischemic myocardial dysfunction (“stunned myocardium”). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 12, 239–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dhalla N. S., Elmoselhi A. B., Hata T., Makino N. (2000) Status of myocardial antioxidants in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 47, 446–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bolli R., Jeroudi M. O., Patel B. S., DuBose C. M., Lai E. K., Roberts R., McCay P. B. (1989) Direct evidence that oxygen-derived free radicals contribute to postischemic myocardial dysfunction in the intact dog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 4695–4699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bolli R., Patel B. S., Zhu W. X., O'Neill P. G., Hartley C. J., Charlat M. L., Roberts R. (1987) The iron chelator desferrioxamine attenuates postischemic ventricular dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 253, H1372–H1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. White M. Y., Tchen A. S., McCarron H. C., Hambly B. D., Jeremy R. W., Cordwell S. J. (2006) Proteomics of ischemia and reperfusion injuries in rabbit myocardium with and without intervention by an oxygen free radical scavenger. Proteomics 6, 6221–6233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Eaton P., Byers H. L., Leeds N., Ward M. A., Shattock M. J. (2002) Detection, quantitation, purification, and identification of cardiac proteins S-thiolated during ischemia and reperfusion. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9806–9811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eaton P., Wright N., Hearse D. J., Shattock M. J. (2002) Glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase oxidation during cardiac ischemia and reperfusion. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 34, 1549–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hertelendi Z., Toth A., Borbely A., Galajda Z., Van Der Velden J., Stienen G. J. M., Edes I., Papp Z. (2008) Oxidation of myofilament protein sulfhydryl groups reduces the contractile force and its Ca2+ sensitivity in human cardiomyocytes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10, 1175–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kohr M. J., Sun J. H., Aponte A., Wang G. H., Gucek M., Murphy E., Steenbergen C. (2011) Simultaneous measurement of protein oxidation and S-nitrosylation during preconditioning and ischemia/reperfusion injury with resin-assisted capture. Circ. Res. 108, 418–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Canton M., Neverova I., Menabo R., Van Eyk J., Di Lisa F. (2004) Evidence of myofibrillar protein oxidation induced by postischemic reperfusion in isolated rat hearts. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 286, H870–H877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kumar V., Kleffmann T., Hampton M. B., Cannell M. B., Winterbourn C. C. (2013) Redox proteomics of thiol proteins in mouse heart during ischemia/reperfusion using ICAT reagents and mass spectrometry. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 58, 109–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stone J. R., Yang S. (2006) Hydrogen peroxide: a signaling messenger. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 8, 243–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schroder E., Eaton P. (2008) Hydrogen peroxide as an endogenous mediator and exogenous tool in cardiovascular research: issues and considerations. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 8, 153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Parker B. L., Palmisano G., Edwards A. V. G., White M. Y., Engholm-Keller K., Lee A., Scott N. E., Kolarich D., Hambly B. D., Packer N. H., Larsen M. R., Cordwell S. J. (2011) Quantitative N-linked glycoproteomics of myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury reveals early remodeling in the extracellular environment. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 10, M110.006833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Møller I. M., Rogowska-Wrzesinska A., Rao S. (2011) Protein carbonylation and metal-catalyzed protein oxidation in a cellular perspective. J. Proteomics 74, 2228–2242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chen Y., Kwon S. W., Kim S. C., Zhao Y. (2005) Integrated approach for manual evaluation of peptides identified by searching protein sequence databases with tandem mass spectra. J. Proteome Res. 4, 998–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huang D. W., Sherman B. T., Lempicki R. A. (2009) Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hosack D. A., Dennis G., Sherman B. T., Lane H. C., Lempicki R. A. (2003) Identifying biological themes within lists of genes with EASE. Genome Biol. 4, R70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Grimsley G. R., Scholtz J. M., Pace C. N. (2009) A summary of the measured pK values of the ionizable groups in folded proteins. Protein Sci. 18, 247–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kyte J., Doolittle R. F. (1982) A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 157, 105–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Paulech J., Solis N., Cordwell S. J. (2013) Characterization of reaction conditions providing rapid and specific cysteine alkylation for peptide-based mass spectrometry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1834, 372–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Duncan J. G., Ravi R., Stull L. B., Murphy A. M. (2005) Chronic xanthine oxidase inhibition prevents myofibrillar protein oxidation and preserves cardiac function in a transgenic mouse model of cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 289, H1512-H1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Canton M., Skyschally A., Menabò R., Boengler K., Gres P., Schulz R., Haude M., Erbel R., Di Lisa F., Heusch G. (2006) (2006) Oxidative modification of tropomyosin and myocardial dysfunction following coronary microembolization. Eur. Heart J. 27, 875–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Held J. M., Danielson S. R., Behring J. B., Atsriku C., Britton D. J., Puckett R. L., Schilling B., Campisi J., Benz C. C., Gibson B. W. (2011) Targeted quantitation of site-specific cysteine oxidation in endogenous proteins using a differential alkylation and multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry approach. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 1400–1410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Parker J., Balmant K., Zhu F., Zhu N., Chen S. (2014) cysTMTRAQ – an integrative method for unbiased thiol-based redox proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics October 14 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sun M. A., Wang Y., Cheng H., Zhang Q., Ge W., Guo D. (2012) RedoxDB – a curated database for experimentally verified protein oxidative modification. Bioinformatics 28, 2551–2552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.