Abstract

The in vivo osteogenesis potential of mesenchymal-like cells derived from human embryonic stem cells (hESC-MCs) was evaluated in vivo by implantation on collagen/hydroxyapatite scaffolds into calvarial defects in immunodeficient mice. This study is novel because no osteogenic or chondrogenic differentiation protocols were applied to the cells prior to implantation. After 6 weeks, X-ray, microCT, and histological analysis showed that the hESC-MCs had consistently formed a highly vascularized new bone that bridged the bone defect and seamlessly integrated with host bone. The implanted hESC-MCs differentiated in situ to functional hypertrophic chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and osteocytes forming new bone tissue via an endochondral ossification pathway. Evidence for the direct participation of the human cells in bone morphogenesis was verified by two separate assays: with Alu and by human mitochondrial antigen positive staining in conjunction with co-localized expression of human bone sialoprotein in histologically verified regions of new bone. The large volume of new bone in a calvarial defect and the direct participation of the hESC-MCs far exceeds that of previous studies and that of the control adult hMSCs. This study represents a key step forward for bone tissue engineering because of the large volume, vascularity, and reproducibility of new bone formation and the discovery that it is advantageous to not over-commit these progenitor cells to a particular lineage prior to implantation. The hESC-MCs were able to recapitulate the mesenchymal developmental pathway and were able to repair the bone defect semi-autonomously without preimplantation differentiation to osteo- or chondroprogenitors.

Introduction

Large, highly vascularized, new bone tissue volumes are required to span clinically problematic bone defect areas. Adult multipotent progenitor cells (e.g., mesenchymal stem cells [MSCs]) from bone marrow or adipose tissue show promise for bone repair1–3 and immunomodulation,4 but there are key shortcomings that continue to prevent their widespread clinical use.5 The use of MSCs is limited by their low frequency in harvested tissues, particularly in advanced-aged patients, their loss of differentiation capacity during in vitro expansion, and significant inter- and intra- donor-dependent variance in bone formation capacity.6–8 Alternative, extra-embryonic sources of MSCs include umbilical cord tissue and the umbilical cord blood. These cells can be harvested from neonatal tissues without ethical concerns or limitations in cell number and, like bone marrow MSCs, express both an immunoprivileged and immunomodulatory phenotype that makes them a potential cell source for MSC-based therapies.9 While the osteogenic potential of these cells have been verified,10,11 there still remains a critical need to identify progenitor cells with the capability to regenerate new bone tissue of substantial volume through direct participation in new bone tissue morphogenesis.

Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) can be expanded indefinitely in vitro and are capable of overcoming the growth limitations encountered with adult MSCs.12–14 While ethical concerns and immune rejection concerns continue to impede the clinical implementation of progenitors derived from hESC, their pluripotency and rapid proliferation rate make them worthy of study even if only as a model system. It is known that the direct transplantation of undifferentiated hESCs induces uncontrollable spontaneous differentiation and teratoma formation instead of the desired healthy, functional tissue.12,15 To prevent teratoma formation, hESCs must be differentiated in vitro toward the desired lineage prior to transplantation, but it is not clear to what extent they must be differentiated prior to implantation. All studies to date that have evaluated the in vivo bone regeneration ability of progenitor cells derived from hESCs have differentiated the cells toward the osteogenic or chondrogenic lineage in culture prior to mouse implantation.16–25 These studies have shown limited, highly variable bone formation that is, at best, similar to bone regeneration by adult MSCs, and often accompanied by tumor formation.23,26 Thus far, the use of a simple protocol for derivation of hESC-MSCs that are capable of reproducible in vivo bone defect bridging bone regeneration, without requiring additional tissue engineering procedures prior to implantation, has not been demonstrated.

It has been suggested that predifferentiation of adult MSCs into chondroprogenitors and further culturing them to establish pellets of neocartilagenous tissue prior to implantation is a means to achieve more vascularized, and accordingly larger volumes, of new bone with MSCs27–29 and mouse embryonic stem cells.30 This process, reminiscent of endochondral bone formation, has several advantages for bone tissue engineering: early vascular onset, and better cell survival in the poor environmental conditions of a wound, such as low oxygen and poor nutrient supply. Selection of the endochondral ossification pathway is also a so-called “developmental engineering” strategy31 that was proposed as a means to optimize in vitro bone tissue engineering of organs. Developmental engineering involves identifying and engineering up to a pivotal developmental step during tissue morphogenesis that, once achieved, triggers semi-autonomous tissue regeneration through an interconnected cascade of events.31 This is in contrast to the typical step-by-step, highly engineered tissue assembly process that often falls short of reconstructing, and then integrating with, the complicated natural tissue structure. Attempts to apply a developmental engineering strategy to achieve bone repair with hESC-derived mesenchymal-like progenitors through endochondral ossification have not yet been successful.30,32

A simple one-step derivation protocol for hESC-mesenchymal progenitor cells (hESC-MCs) has previously been reported33 that does not involve complicated cell sorting, co-culturing with other cell types, or osteo- or chondroblast differentiation procedures utilized by others.12,21–23,26 The restricted in vitro osteochondrogenic differentiation capacity of these cells,33 combined with their highly proliferative nature, led us to the hypothesis that these hESC-MCs would be capable of substantial in vivo bone repair without any preculturing or bone growth directives prior to implantation in a bony defect. The goals of this study were to (1) evaluate the in vivo regeneration of mouse calvarial bone defects by hESC-MCs when implanted directly without induced differentiation to osteo- and chondroprogenitors; (2) rigorously assess whether the hESC-MCs directly participated in new bone formation, as evidenced by confirmation of the presence of human cells in the newly formed tissue and production of osteogenic proteins; and (3) compare the bone morphogenesis mechanism of the hESC-MCs with adult MSCs in the same animal model.

Materials and Methods

Derivation of hESC-MCs and control adult MSCs

Prior to initiating the mesenchymal cell derivation procedure, H9 hESCs (WiCell) were maintained feeder-free on Matrigel™ Basement Membrane Matrix (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California) in mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF)-conditioned medium supplemented with 4 ng/mL bFGF. Matrigel is commonly used now as a cell culture substrate instead of MEFs because it prevents contamination of the human cells with the mouse feeder cells, and eliminates the need for multiple passages to remove the nonproliferating cells prior to initiating a differentiation protocol. Following Boyd et al.,33 colonies of feeder-free H9 hESCs (WiCell) were passaged onto laminin-coated 35 mm tissue culture plates (NUNC) and cultured in MEF-conditioned medium. At 90% confluence, the medium was changed to microvascular endothelial growth media (EGM2-MV) (Lonza Corporation) followed by three passages onto tissue culture plastic to initiate an epithelial to mesenchymal transition. The media was replenished every other day over a period of 3 weeks until cells took on a uniform epithelial appearance. Cells were then trypsinized and passaged to tissue culture-treated T75 flasks. For the first passage, cells were seeded at a density of 40,000 cells/cm2 (e.g., cells from one well of a six-well plate were transferred to a T75 flask). For subsequent passages they were seeded at a density of 13,000 cells/cm2 and grown to confluence over 5–7 days. The cells developed a homogenous fibroblast-like morphology during three passages and were then trypsinized and frozen. The cells were thawed and cultured in MSC expansion medium αMEM, 10% MSC-qualified FBS (Hyclone), 1% Pen/Strep, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 100 μM nonessential amino acid, as were the adult MSCs, prior to implantation. The derivation was repeated thrice and by two different people in two separate laboratories. The in vitro and in vivo study results from all preparations were similar. The control adult hMSCs were purchased from Lonza Corporation (PT-2501, Lot F3674, 22-year-old female) and were confirmed to have tri-lineage potentiality by the company. The adult hMSCs were cultured in MSC expansion medium. Flow cytometry of both cell types was conducted to confirm expression of typical MSC markers prior to implantation.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was run on a BD LSR II Flow Cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Cells growing in MSC expansion medium were harvested and separately labeled with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-human CD73 antibody (BD Pharmingen), FITC-conjugated anti-human CD90 (Thy1) antibody (eBioscience), PE-conjugated Anti-human CD105 antibody (eBioscience), FITC-conjugated Anti-human CD34 antibody (BD Pharmingen), and Pacific Blue (PB)-conjugated Anti-human CD45 antibody (eBioscience). Unstained cells and isotype controls were used. Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.). Cells were also analyzed for the presence of multipotentiality markers and undifferentiated hESC markers: PerCP-Cy5.5 NANOG (562259; BD Biosciences), PE-conjugated Sox2 (560291; BD Biosciences), PE-conjugated Tra-1-81 (330707; Biolegend), Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated Tra-1-60 (330605; Biolegend), AlexaFluor 488-conjugated SSEA-4 (330411; Biolegend), and eFluor 660-conjugated OCT3/4 (50-5841-80; ebioscience) (all anti-human).

In vitro osteogenic differentiation

To assess the in vitro osetogenic capability of the cells, both hESC-MCs and adult hMSCs were plated in a proliferation medium containing alpha minimum essential medium (alpha-MEM), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone), 100 U penicillin-100 μg/mL streptomycin (1% Pen/Strep), and 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid phosphate- magnesium salt (AA-P), at a density of 15,000 cells/cm2. Upon confluence, medium was changed to osteogenic medium that contained alpha-MEM, 10% FBS, 1% Pen/Strep, 100 nM dexamethasone (Dex), 50 μg/mL AA-P, and 2 mM beta-glycerophosphate (bGP). To further probe the differentiation status in one group, the medium was changed to alpha-MEM with 10 nM 1,25- dihydroxyvitamin D3, 1% pen/strep, and 50 μg/mL AA-P at 24 h before the final time point (28 days). The presence of mineralized matrix was assessed using xylenol orange staining, as described previously.34

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Gene expression was analyzed by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-PCR). RNA obtained from TRIzol extractions was used for cDNA synthesis using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) performed on the iCycler® Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's instructions. TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) of RUNX2, COL1a1, ALP, OCN, and BSP were used to detect markers of osteoblastic differentiation (assay IDs: ALP- Hs00758162_m1, BSP- Hs00913377_m1, Col1a1- Hs00164004_m1, OCN- Hs01587813_g1, Runx2- Hs00231692_m1, and GAPDH- Hs99999905_m1). GAPDH was included as an internal control. Quantification was performed by Delta-Delta Ct method. Results were normalized to day 0 expression levels. Three samples were pooled for each time point. The hESC-MC experiments were repeated and the data from the two different experiments combined for the graph.

Animal study

All experimental protocols were approved prior to the study in accordance with the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals at the University of Connecticut Health Center. Cells were directly implanted on a commercially available collagen/hydroxyapatite scaffold (Healos®; DePuy Synthes) immediately after the differentiation to mesenchymal progenitors without any osteogenic or chondrogenic differentiation procedures nor addition of osteogenic agents. The Col/HA material is supplied as a thick sheet, which was first reduced in thickness to 1 mm and then a tissue punch was used to cut out a 3-mm diameter disk. The scaffold material expands slightly when it becomes wet and thus reaches a 3.5–4.0 mm size after using it to absorb the cells. According to the manufacturer, the scaffold has 99% porosity with average pore size 4–200 μm. The scaffold is constructed with cross-linked xenogenic type 1 collagen fibers that are fully coated with hydroxyapatite through a proprietary 360° accretion process. This scaffold is clinically used with autogenous bone marrow aspirate and provides an excellent environment for osteoprogenitor cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation.35 To load cells on the scaffold, 1 million cells were concentrated into a pellet by centrifugation in 15 mL tubes, the medium was removed and the highly absorbable Col/HA sponge was held with forceps and used to wick up the cell pellet. The cell-loaded scaffolds were directly placed into 3.5 mm critical sized craniotomy defects in the parietal bones of 4 to 6 month old female immune deficient NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (Jackson labs; stock no. 005557). Our unpublished studies have shown these defects will not heal on their own. The periosteum overlying the calvarial bone was completely resected prior to implant placement. The incision was closed with vicryl sutures (Ethicon/Johnson and Johnson). Mice were euthanized 6 weeks after surgery by CO2 inhalation and their calvaria were removed for X-ray and histological examination.

X-ray and microcomputed tomography imaging

Calvarial bone samples were X-rayed using a Faxitron MX-20 X-ray cabinet (Faxitron). Images were acquired using a 28 kV exposure for 4 s at a distance of 20.9 cm from the source. The images were then captured and stored using the Faxitron DX software (version 1.00). Bone formation within parietal bone defects was quantified in living animals using conebeam micro-focus X-ray computed tomography (VivaCT40; Scanco Medical AG), calibrated to a step-interval hydroxyapatite phantom. VIVA-CT was used to analyze the tissue at 3 and 6 weeks. Anesthesia was induced and maintained using 2–3% isoflurane in oxygen. Serial tomographic images of the skull were acquired at 55 kV and 145 μA, collecting 2000 projections per rotation at 250 ms integration time. Three-dimensional 16-bit grayscale images were reconstructed using standard convolution back-projection algorithms with Shepp and Logan filtering, and rendered within a 38.9 mm field of view at a discrete density of 145,794 voxels/mm3 (isometric 19-μm voxels). New bone formed within the parietal defects was discernible from original bone by virtue of lower mineral density, visibly evident through 6 weeks of healing, allowing manual segmentation via inspection of serial two-dimensional images. Further segmentation of bone from marrow and soft tissue was performed in conjunction with a constrained Gaussian filter to reduce noise, applying a hydroxyapatite-equivalent density threshold of 505 mg/cm3.

Histological and immunohistochemical analysis

For histology, retrieved tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution (Sigma; HT501320.9) at 4°C for 2–3 days and then decalcified in 10% EDTA for 3 days. Decalcified calvarial bones were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm. Deparaffinized sections were stained with the Alu Positive Control Probe II cocktail in a Ventana Ultra IHC/ISH automated staining instrument, as per the manufacturer's instructions. The Alu probe consists of 2,4-dinitrophenyl (DNP)-labeled DNA probes to human Alu sequences; the DNP probe detected using the ISH iVIEW(tm) Blue Plus Detection Kit.

For type II collagen antibody staining, hydrated sections were incubated for 10 min in 1 mg/mL pronase (Sigma) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5 mM calcium chloride at room temperature, washed and incubated in anti-type II collagen antibody (clone II-II6B3 supernatant; DSHB) diluted in PBS/BSA (1%) 1/500, overnight at 4°C, followed by a 1 h incubation in biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG (Vector Labs) diluted 1/2,000, and then for 45 min in streptavidin-HRP (GIBCO) diluted 1/400. Vectorshield VIP peroxidase substrate was applied for 10 min and slides were counterstained in 0.05% Fast Green in 3.5% glacial acetic acid and 96.5% ethanol (v/v).

Cryohistological analysis

Calvaria were harvested and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution (Sigma, HT501320.9) at 4°C for 2–3 days. Samples were then soaked overnight in 30% sucrose/PBS solution and embedded in Neg-50 frozen section medium (Richard-Allan Scientific). A nonautofluorescent adhesive film (Section Lab, Co., Ltd, Toyota-gun) was used to capture the cut section (5 μm). The film was adhered, section side up, to a glass slide using a 0.2% chitosan (C3646; SIGMA) solution in 0.25% acetic acid and allowed to dry for 48 h at 4°C. The glass slide was soaked for 10 min in PBS and a cover slide put on with 50% glycerin in PBS prior to microscopy for the endogenous fluorescent signals (scaffold and bone mineral). After a section was imaged for endogenous signals, the cover slide was removed by brief soaking in PBS and then processed for additional staining.

For immunohistochemistry, frozen and paraffin section were rinsed with PBS and blocked with 5% normal goat serum and 1% BSA in PBS for 1 h at RT. The sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with a 1:100 dilution of Mouse anti-Human Mitochondria (huMit) (Cat# MAB1273; Millipore)) or Mouse anti- Human Bone Sialoprotein (BSP) (Cat# MAB1061; Millipore) in 1% normal goat serum and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS. After rinsing with PBS, the slides were incubated with 1: 100 dilution FITC or TRITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG at room temperature for 1 h. Then the slides were washed and mounted with 50% glycerin in PBS with 1:1000 diluted Hoechst 33342 (Mol Probes; #H-3570). The sections were imaged using a Zeiss Imager Z1 microscope (Carl Zeiss) using Axio Vision Rel.4.7 (Carl Zeiss). The fluorescent signals were captured by a grayscale Zeiss Axiocam and pseudo-colored to provide a visual contrast between the filters. The alizarin complexone (AC) mineralization line was captured utilizing a TRITC filter (Chroma 49005ET), and FITC was captured with a YFP filter (Chroma 49003). To stain for alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity, the cover slide was removed and the section was incubated in the AP reaction buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 9.5, 50 mM MgCl2, and 100 mM NaCl) for 10 min followed by reaction buffer containing 0.2 mg/mL Fast Red TR (Sigma; #F8764-5G) and 0.1 mg/m Naphthol AS-MX Phosphate (Sigma; #N-4875) for 5 min. Imaging was done using an RGB chromogenic filter set (Zeiss; #487933) and reconstructed to provide a visual color image.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD). Statistical difference for the RT-PCR study was assessed with a Student's t-test, two tailed with significance set at at p<0.05. Statistical significance for the micro computed tomography (microCT) study was assessed with a nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparison post test with significance set at p<0.05.

Results

Derivation and characterization of mesenchymal progenitors from hESC

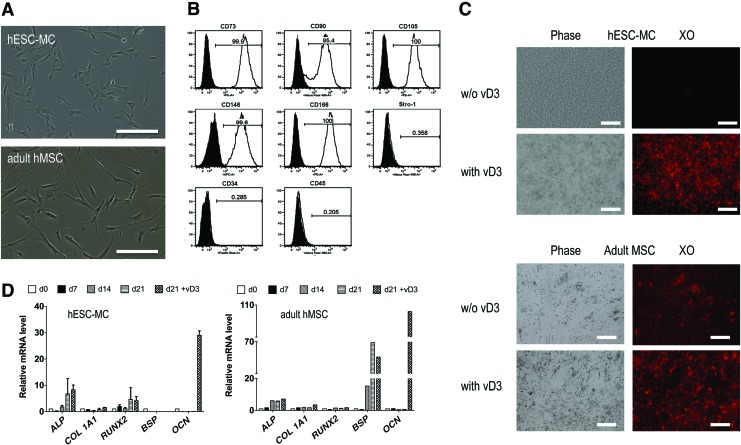

hESC-MCs were derived from H9 hESCs (WA09; WiCell) as previously described,33 except the cells used in this study were already feeder-free since they were grown on Matrigel™, and thus could be directly plated on laminin to initiate the EMT derivation process without the need for multiple prepassaging procedures. The hESC-MCs have a fibroblastic morphology resembling adult hMSCs (Fig. 1A). Flow cytometry analysis of the hESC-MCs for markers of adult MSCs demonstrated they were positive for CD73 (99.9%), CD90 (85.4%), CD105 (100%), CD146 (99.6%), and CD166 (100%), and were negative for the hematopoietic markers CD34 and CD45 (Fig. 1B). These values were nearly identical to those obtained for the control adult hMSCs, except that the hESC-MCs had lower Stro-1 expression than adult hMSCs (0.3% vs. 11%). To confirm that the derivation process had removed undifferentiated cells, a panel of pluripotency markers was run on the hESC-MCs and the control adult hMSCs: SSEA-4, Oct 3/4, Nanog, SOX2, Tra-1-60, and Tra-1–181. Both cell types were negative for the undifferentiated hESC markers Tra-1-60 and Tra-1-181 (<2%). Interestingly, both cells were positive for markers commonly used for undifferentiated pluripotent hESCs, but now known to be associated with adult multipotential cells as well, such as SSEA-436 and Oct4, Nanog, and SOX2.37 The percent of cells positive for SSEA-4 was 60% for hESC-MCs versus 35.5% for adult hMSCs. For Oct3/4, the percent of hESC-MC cells expressing the marker was 85.8 versus 94.1% for adult hMSCs, for Nanog, 67.8% positive in hESC-MCs versus 63.7% in adult hMSCs, and lastly, 100% of hESC-MCs were positive for Sox 2 versus 99.9% for adult hMSCs.

FIG. 1.

Morphology and phenotypic analysis of osteochondroprogenitors derived from hESCs (hESC-MCs). (A) As seen in phase contrast, the hESC-MC cell morphology is similar to that of adult MSCs, although adult MSCs have more elongated filopodia. Scale bars are 20 μm. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of hESC-MCs demonstrates their expression of typical adult MSC surface markers. The percent expression of MSC surface markers was similar for adult hMSCs and the hESC-MCs except for Stro-1. (C) Phase contrast and fluorescent images of xylenol orange-stained cultures of both cell types at 21 days in osteogenic medium. Mineralization was not observed in the hESC-MC cultures without vD3 spiking. (D) Representative real-time quantitative PCR analysis of gene expression of the hESC-MC and hMSC osteogenic cultures. Genes were quantified and reported relative to day zero undifferentiated gene expression. GAPDH was used as internal control. The osteogenic differentiation of adult MSCs was more efficient and complete than that of hESC-MCs as evidenced by induction of BSP and stronger OCN expression in response to vD3. Scale bars are 20 μm. hESC-MCs, mesenchymal-like cells derived from human embryonic stem cells; hMSC, human mesenchymal stem cells; BSP, Bone Sialoprotein; OCN, osteocalcin; VD3, vitamin D3. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

In vitro osteoblast differentiation of hESC-MCs relative to adult hMSCs

The derived hESC-MCs and controls of adult hMSCs were characterized prior to animal implantation for their ability to mineralize and differentiate in vitro into osteoblasts during cell culture in the presence of osteogenic medium. After 21 d of culture in osteogenic medium there was no evidence of mineralization in the hESC-MC cultures, while the control adult MSCs had deposited a mineralized matrix as evidenced by positive xylenol orange staining (Fig. 1C). The lower bGP content in the osteogenic medium of these studies (4 mM rather than 10 mM) avoids nonosteoblast-specific mineral deposition that can occur at 10 mM.38 To further probe the differentiation status of the cells, 1,25- dihydroxyvitamin D3 (vD3) was added at day 21 to the cultures because it is known to accentuate osteoblast gene expression if cells have begun to differentiate to the preosteoblast phase.39 vD3 administration initiated mineral matrix deposition in the hESC-MCs and increased the mineralized matrix deposition in the adult MSC cultures as evidenced by increased xylenol orange staining (Fig. 1C). RT-PCR analysis of a panel of osteogenic genes showed some evidence of osteogenic differentiation without vD3, but there were no statistically significant increases over day 0 cells for the hESC-MCs (Fig. 1D). Osteogenic medium stimulated the adult MSCs to express BSP, up to 70-fold increases over day 0 values, but BSP expression was not observed in the hESC-MC cultures at any time point. After 24 h exposure to vD3, the OCN gene expression was dramatically upregulated in both cultures (Fig. 1C): 30-fold in the hESC-MCs and 100-fold in the adult hMSCs.

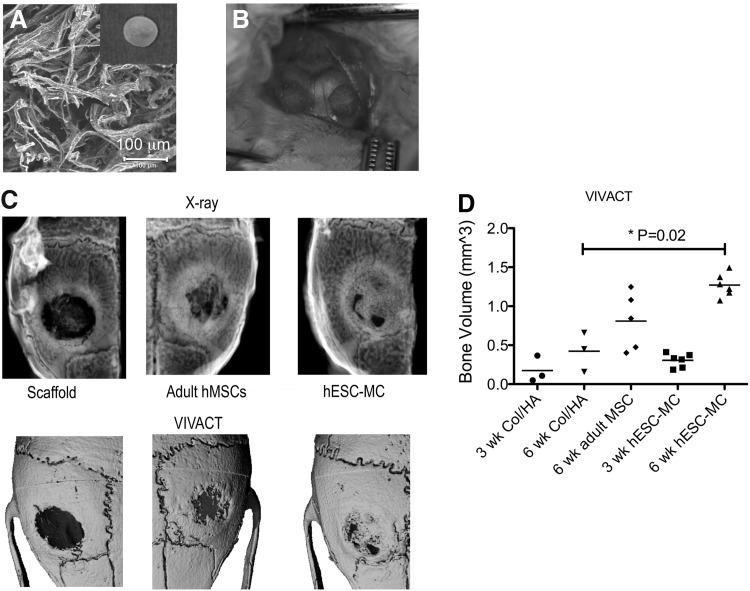

Repair of mouse calvarial bone defects by implantation of hESC-MCs versus adult hMSCs on a collagen/hydroxyapatite scaffold

To investigate the in vivo bone repair capability of the hESC-MCs, 1×106 cells were loaded onto a fibrous collagen/hydroxyapatite (Col/HA) scaffold35 (Fig. 2A) and immediately implanted into dual critical-sized calvarial defects in the left and right parietal bones of immune deficient NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NOD scid gamma) mice (Fig. 2B). Each mouse received two identical implants to avoid problems with cell crossover that is possible in adjacent calvarial defects. Adult hMSCs on Col/HA scaffolds, and Col/HA scaffolds alone, were also implanted into additional mice as controls. After 6 weeks, X-rays and live microCT imaging confirmed nearly complete bridging of the calvarial bone defect in all six mice of the hESC-MC group, while the adult hMSCs showed a wide range of new bone growth primarily located at the defect edges (Fig. 2C). Live microCT imaging of the bone defects at initial and intermediate time points of the hESC-MC and scaffold only groups revealed that the initially radiolucent defect areas were progressively filled with mineralized tissue in the hESC-MC group (Fig. 2D). Quantification of bone volume showed that the defects treated with hESC-MCs consistently regenerated three times more new bone volume (p=0.02) compared with biomaterial scaffold alone (Fig. 2D). This was greater than the adult hMSC group which, on average, regenerated two times more new bone than biomaterial scaffold alone but was not statistically different than scaffold only. The highly variable performance of the adult MSCs40 has been previously reported and may account for the nonsignificant differences between adult MSCs and biomaterial scaffold alone and between adult MSCs and the hESC-MCs.

FIG. 2.

Substantial mouse calvarial bone defect regeneration was observed following in vivo implantation of hESC-MC/scaffold constructs. (A) Scanning electron micrograph of the fibrous collagen/hydroxyapatite scaffolds used for the cell implantation studies (disk scaffold shown in inset). (B) Dual 3.5 mm calvarial bone defects in NOD scid mice were used to evaluate bone tissue morphogenesis at 3 and 6 weeks. (C) The X-rays (top row) and live microCT (VIVACT) scans (bottom row) at 6 weeks demonstrate substantial new bone tissue morphogenesis throughout the defect by the hESC-MC cells (far right) as compared to scaffold only (far left). Adult MSCs (middle) stimulated bone tissue regeneration primarily at the defect edges. Images shown represent mid-range performance. (D) Quantitative analysis of the VIVA-CT data demonstrated that significantly more bone was formed in the hESC-MC group than the scaffold only group (p=0.02). The variable bone formation of the adult hMSCs was not statistically significant different than scaffold or hESC-MC (p>0.05).

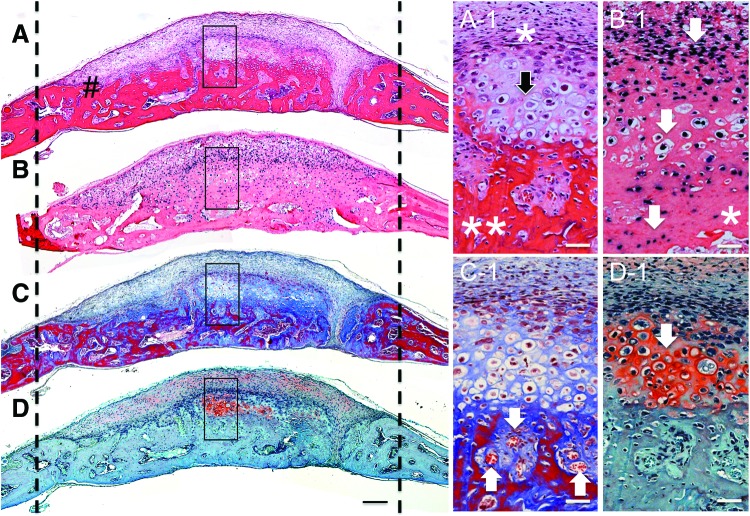

Endochondral ossification is prevalent during in vivo osteogenesis by hESC-MCs, but not observed in adult MSCs

H and E-stained frontal sections of the bone defect sites implanted with hESC-MCs revealed a mineralized, layered, regenerative neotissue throughout the defect at 6 weeks (Fig. 3A). A vascularized, marrow and osteocyte-containing bony matrix was present at the bottom closest to the dura (Fig. 3A**) with an overlay of cells with a hypertrophic chondrocyte morphology (Fig. 3A-1 black arrow) which, in turn, was covered by a thin layer of fibroblast-like cells (Fig. 3A-1*) and followed by a thicker layer of small cells without a distinguishing morphology. To better appreciate the relative contribution of human and mouse cells to the newly formed tissue, a neighboring tissue section was used for in situ hybridization of human specific Alu sequences (Fig. 3B). The layered, regenerative neotissue was heavily positive for Alu and the labeling continued into the osteogenic layer adjacent to the dura, although it became less prominent at the deepest level adjacent to the dura, as seen at higher magnification (Fig. 3B-1 *). Alu labeling was less populous toward the mouse bone defect edges and adjacent to the dura, indicating host participation in bone regeneration in these areas. There was a seamless integration of the human cell-initiated bone tissue and the host-initiated tissue at the defect edges indicating concerted participation of both host and donor (Fig. 3A#). Positive staining for Alu throughout the mineralized neotissue in the central portion of the defect confirmed that the majority of the newly formed tissue was of human origin. The trichrome-stained samples reveal sites of active mineralization occurring throughout the regenerating bony tissue (blue unmineralized collagenous matrix transitioning to red mineralized matrix, Fig. 3C). There were numerous vascular channels and regions of bone marrow development of mouse host origin within the newly formed bone (Fig. 3C-1 white arrows). Further evidence of hESC-MC differentiation into functional hypertrophic chondrocytes was shown with saffranin-O-positive cartilagenous matrix in areas corresponding to Alu+ labeling (Fig. 3D, D-1 white arrow). These areas stained positive for collagen II (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea). Host mouse cells were not found as hypertrophic chondrocytes, only as osteoblasts. No evidence of teratoma formation was found in any of the mice implanted with hESC-MCs during any of the studies at any of the time points.

FIG. 3.

Extensive new bone tissue morphogenesis by hESC-MCs through endochondral ossification. Stained frontal histology sections of samples harvested at 6 weeks (A) H and E, showing integration of new tissue with host bone (#) (B) Alu in situ hybridization, (C) Masson's trichrome, and (D) saffranin-O. The dashed lines indicate approximate original defect edges. Higher magnification areas are indicated by black boxes in the low magnifications. (A-1) A layered, highly cellular regenerative neotissue is present throughout the defect at 6 weeks. The fibroblastic cells are condensed closest to the mineralized tissue edge (*) and below this are cells with characteristics of hypertrophic chondrocytes (black arrow) directly above the bony tissue with osteocytes (**). (B-1) Darkly stained Alu-positive hESC-MCs are present throughout the neobone tissue confirming their involvement with the repair process. The highly cellular layer above the mineralized tissue, the hypertrophic chondrocytes and the osteocytes in bone (shown by arrows) are all Alu-positive hESC-MCs. The deepest bony tissue adjacent to the dura (*), and that directly in contact with host bone edges contained a combination of Alu-positive and Alu-negative cells indicating involvement of host progenitors in concert with the implanted cells in these areas. (C-1) White arrows indicate vascularized marrow channels within the new bony tissue. Mature (red) mineralized matrix bridges through the center of the defect. (D-1) Safffranin-O-positive stain (white arrow) confirms the presence of a cartilaginous precursor tissue. Scale bar in A–D is 200 μm and the scale bars in the corresponding higher magnifications are 50 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

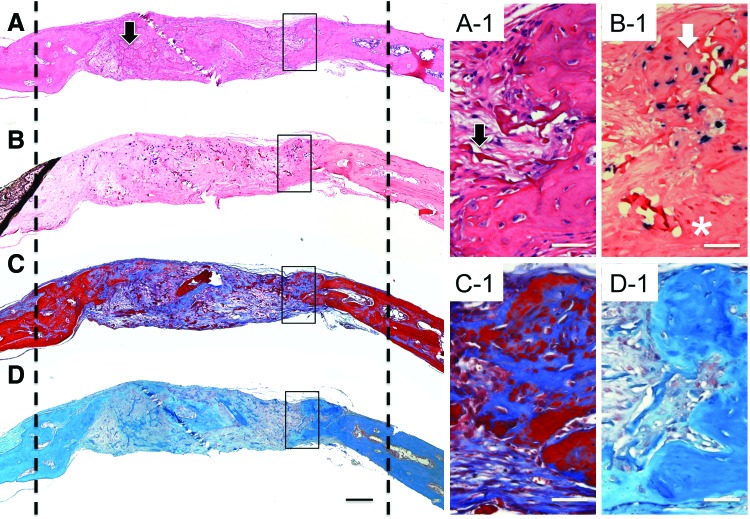

H and E-stained sections of the adult hMSCs samples (Fig. 4A), also retrieved at 6 weeks, had wispy trabeculae of disorganized bone interspersed with fibrous tissue in the central portion of the defect (black arrow) and dense new bone adjacent to the edges of the defect marked with dashed lines. In contrast to the hESC-MC samples, there was no layered cellular structure in the hMSC samples and the new mineralized tissue was not highly vascularized. Alu-positive hMSCs were detected predominantly in the central, nonmineralized portion of the defect and to a much lesser extent within the newly formed bony tissue (Fig. 4B, B-1). The trichrome-stained sections showed fewer areas of mineralization (red) in the adult MSC samples than the hESC-MC samples (Fig. 4C). No saffranin-O-positive staining was observed in the adult MSC samples (Fig. 4D, D-1) indicating a lack of differentiation to chondrocytes. Histological analysis of the cell-free scaffold confirmed it was an appropriate negative control as evidenced by the lack of bone defect healing and the absence of human cells in Alu-stained sections (Supplementary Fig. S2).

FIG. 4.

Regenerative bony tissue by the adult MSCs formed by an intermembraneous ossification mechanism at defect edges. Stained frontal histology sections of tissue retrieved at 6 weeks: (A) H and E, (B) Alu in situ hybridization, (C) Masson's trichrome, and (D) saffranin-O. The dashed lines indicate the original bone defect edges. Higher magnification areas indicated with black boxes. (A-1) Newly formed bony tissue was primarily observed as an outgrowth of the host bone at the defect edges consistent with intermembraneous bone formation. Residual scaffold material was found throughout the central portion of the defect (black arrow on low and high mag images). (B-1) Alu-positive hMSCs were present throughout the unhealed defect area and observed in only a small fraction of the total newly regenerated bony tissue (white arrow) and absent in others (*). (C-1) Minimal vascularization observed in the new tissue. (D-1) No areas of positive saffranin-O staining associated with chondrocytes were found in the adult hMSC samples. Scale bar in A–D is 200 μm and the scale bars in the corresponding higher magnifications are 50 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

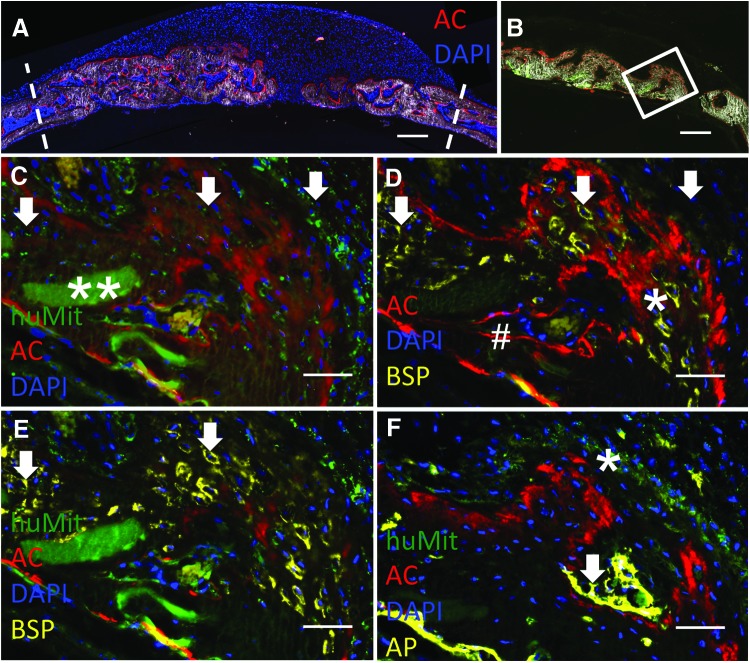

Cryohistology method confirms production of human osteogenic proteins by the hESC-MCs and direct participation in bone morphogenesis

We have developed a cryohistological method for nondecalcified skeletal tissues to better appreciate the dynamic activity of the bone regeneration process and to determine the relative contribution of the mouse and human cells to the repair process. In the scan of the total implant cross section (Fig. 5A) mineralized tissue is visualized by a combination of dark field imaging and the red label of AC which identifies active mineral deposition at the 6-week tissue harvest time point. DAPI nuclear staining reveals the highly cellular regenerative tissue overlying the new bone formation (Fig. 5A). Sections were subsequently stained for human-specific mitochondrial antibody (huMit) to identify the subset of human cells both within and above the newly formed bone. The white box in another low magnification scan (Fig. 5B) shows where the high magnification immunohistochemistry images are taken from. Positively stained human cells (green, white arrows) were identified within all layers of the neotissue, for example, the proliferative and hypertrophic chondrocyte layers, and most importantly, the new bony tissue that was AC+ provided evidence that the human cells were involved in the deposition of bone still actively occurring at 6 weeks (Fig. 5C). The co-localization of the red and green colors are most easily seen in these merged images, but single color panels for Figure 5 are also provided (Supplementary Fig. S3 and S4). The red AC stain appeared in two formats: sharp lines and broad diffuse areas and represent the different bone formation mechanisms. The sharpest AC lines were found in the host mouse bone (Fig. 5D#) and represent intermembraneous direct bone deposition while the more diffuse staining was found in the areas with hypertrophic chondrocytes. The autofluorescence of the collagen/hydroxyapatite scaffold enabled it to be detected within the newly mineralized tissue (Fig. 5, **). An additional series of sequential stains and imaging was performed to relate osteogenic cellular activity (human specific BSP immunoreactivity, AP, and active mineralization) to the source (i.e., host vs donor) of the osteogenic cells. Fig. 5D (*) shows human-specific BSP (yellow) within the diffuse red mineralization areas at the same places where the huMit signals are located indicating that the human cells are producing an osteogenic protein in the bony tissue. Figure 4E is an overlay of the huMit, human BSP, AC, and DAPI staining more clearly demonstrating the association of the human BSP with the huMit-positive hESC-MCs (white arrows). Diffuse areas of AP staining correlated with huMit-positive cells (Fig. 5F *) in contrast to the much stronger and sharply defined AP signal in areas of mouse bone formation closest to the dura (arrow). There is a seamless integration of the mouse and human bone but the host vs donor origin of the cells can be easily seen by the two different methods used in these studies: Alu in situ hybridization and the huMit immunofluorescent staining. Participation of the mouse dural progenitors in human cell implantation studies in the calvarial site is expected closest to the dura, based on previous studies.41 In summary, the nondecalcified cryohistology further demonstrates that the hESC-MCs are undergoing an endochondral bone formation process with expected expression of human BSP within the diffuse areas of mineralization, which is produced by hypertrophic chondrocytes and osteoblasts.42–44 In contrast, areas of strong and linear AP activity are associated with a distinct AC mineralization line and less often with huMit+ cells (Fig. 5F, white arrow) indicating a subset of the mineralizing tissue originates from murine osteoblasts and that intermembraneous ossification is the dominant mechanism for the host osteoprogenitors.

FIG. 5.

hESC-MCs actively participate in bone tissue regeneration as evidenced by expression of human osteogenic proteins. (A) A low magnification scan showing the entire defect area at 6 weeks. Dashed lines indicate approximate original defect edges. Active mineralization throughout the defect is visible by red AC staining. Nuclear DAPI staining (blue) and dark field imaging allows the visualization of the cellular and mineralized components of the neotissue. Scale bar is 300 μm. (B) A low magnification scan of a different sample without DAPI staining with a white box indicating where the high magnifications of (C–F) are obtained. Scale bar is 200 μm. (C) Merged image of huMit (green) and AC (red) and DAPI (blue) demonstrates that positively stained hESC-MCs are found throughout the layers of new bony tissue (arrows) with less huMit staining closest to the dura. Scaffold material can be seen embedded within the mineralized tissue (**) Single color panels for C, D, and E are available as Supplementary Fig. S3. (D) Merged image of AC (red), DAPI (blue), and BSP (yellow), showing human BSP expression is co-located with the actively mineralizing tissue (red). Bright red lines indicate host bone (#). White arrows are located in the same areas as the white arrows in (C) for reference. (E) Merged image of huMit (green), AC (red), DAPI (blue), and BSP (yellow) reveals a co-localization of the human cells and BSP expression (arrows). (F) Merged image of huMit (green), AC (red), DAPI (blue), and AP (yellow) shows co-localization of a second osteogenic protein–alkaline phosphatase (AP) with human cells. Single color panels for F, which is a different section than C, D, and E are available as Supplementary Fig. S4. Scale bars in C–F are 50 μm. AC, alizarin complexone. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

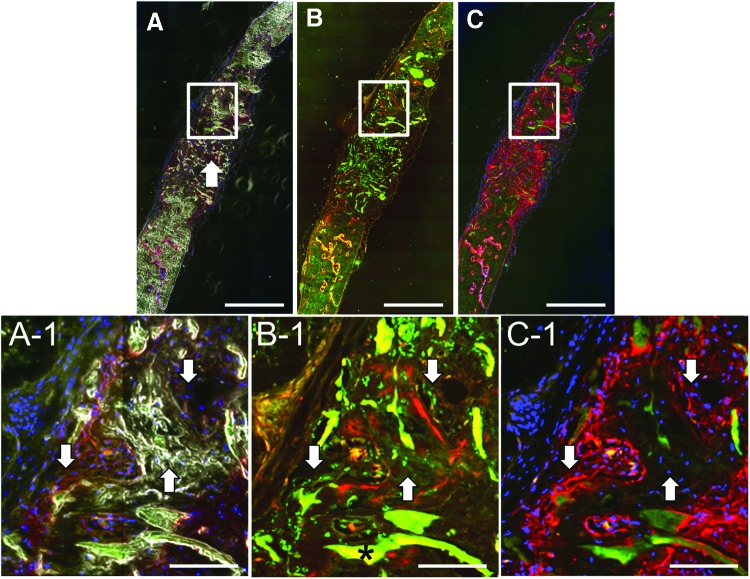

The cryohistology technique applied to the adult MSC samples produced images with large amounts of residual scaffold and exclusively sharp red AC mineralization lines in contrast to the broad diffuse mineralization areas seen in the hESC-MC samples (Fig. 6A, B). Despite the substantial number of adult MSCs identified in the middle region of the defect, no bone formation occurred here. A few huMit-positive adult MSCs were found in and around the AC+ mineralizing areas and mineralized matrix identified by bright field imaging closest to the original defect edges (Fig. 6A-1, B-1). AP production was most often associated with host cells in the adult MSC samples, although in some areas huMit-positive cells (Fig. 6B-1 left arrow) were found adjacent to the AP positive stained mineralization fronts (Fig. 6C-1 left arrow). Single color images for Figure 6 are included as Supplementary Figure S5. BSP staining was not completed on adult MSC samples since the AP analysis was consistent with previous reports and previously BSP RNA has been isolated from retrieved adult MSC samples,45 and thus it was expected to yield little new information.

FIG. 6.

Adult hMSCs have limited participation in the formation of new bony tissue in the calvarial defect. (A) A low magnification merged image of a DAPI (blue) and AP (red orange) stained sample with dark field imaging. Extensive amount of residual scaffold remains (arrow). (B) A low magnification merged image of huMit (green) and AC (red) channels. (C) A low magnification merged image of an AP-stained sample (red pink) with DAPI (blue). Scale bars are 200 μm. White boxes identify the high magnification areas of (A-1, B-1 and C-1). (A-1) The dark field imaging shows areas of new bony tissue (lower right arrow) and residual scaffold (*) in a light gray color. Arrows shown in same location in each high magnification area for reference. Scale bars are 50 μm in A-1, B-1, and C-1. (B-1) Adult hMSCs with punctate green huMit staining (white arrows) are found in proximity to, and within, areas with perimeters positively stained with the red AC mineral label, which indicates newly formed mineralized tissue. Positive AC label shown below upper right arrow. Dark star identifies a piece of residual collagen/calcium phosphate scaffold that autofluoresces at red and green wavelengths. (C-1) Arrow on left points to adult hMSCs [blue DAPI staining that were huMit positive in (B-1)] that are adjacent to and have positive osteogenic AP staining (red pink) at the mineralization front. Arrow on right points to adult hMSCs residing within the mineralized tissue no longer actively expressing AP. Single color panels are provided as Supplementary Figure S5. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Discussion

This study represents a key step forward for bone tissue engineering because of the large volume, vascularity, and reproducibility of new bone formation by hESC-MCs within mouse calvarial bone defects. Previous studies have demonstrated that hESC-derived progenitor cells have some in vivo osteogenic potential,17,21,22,46 but have not approached this level of substantial, repeatable bone formation in a bony defect. For example, despite extensive screening of quite complex protocols for derivation of the cells23 and the addition of 1 μg/implant of bone morphogenetic protein−2 known to regenerate bone by itself,21 the previous subcutaneous implantation studies of hESC-derived progenitors20–23,32 have not demonstrated large, consistent, tumor-free volumes of bone of proven human origin. The hESC-progenitor studies completed in the same murine calvarial defect model as used in the present study have shown only inconsistent partial bone defect repair conclusively associated with the implanted hESC-progenitor cells19,24,26 despite the use of hydroxyapatite-containing scaffolds demonstrated to be conducive to achieving in vivo osteogenesis with adult MSCs.47–49 As compared to the previous studies with hESC-derived progenitors, the amount of new bone formation seen in the present study is much greater (approximately 80% defect fill by X-ray analysis), more consistent, and of definitive human origin.

The results of the present study are noteworthy because for the first time the advantages of not over-committing hESC-derived progenitor cells to a particular lineage prior to implantation were demonstrated. Large volumes of vascularized new bone were formed by the implanted hESC-MCs without the need for any preimplantation treatment with osteogenic or chondrogenic inductive medium or agents. Previous protocols have used medium and cocultures and flow cytometry sorting known to support stem cell differentiation into osteoblasts or chondrocytes.17,18,23,26,32 In contrast, the hESC-MCs in this study were derived in medium originally developed for the extended and enhanced growth of lung microvascular cells.50 Thus, the protocol used to derive the hESC-MCs in this study substantially differs from previous approaches to generate progenitors evaluated for in vivo bone repair capability. By not overcommitting these progenitor cells to a particular lineage prior to implantation, the hESC-MCs of this study were maintained in a highly proliferative, plastic phenotype capable of a robust response to the in situ cues from the bone defect. This is consistent with the concept of developmental engineering.31 Additional studies with the hESC-MCs used in this study have demonstrated that they can stabilize endothelial cell networks, thereby functioning like microvascular mural or perivascular progenitor cells.51,52 Perivascular cells are known to contribute to healing of a fracture callous;53 thus, these cells appear to be stimulating new tissue in a manner similar to what occurs in a fracture callous. The weak in vitro osteogenic differentiation performance of the hESC-MCs in this study relative to adult hMSCs (Fig. 1C) was not predictive of the outstanding in vivo performance of the hESC-MCs implanted into calvarial defects, most likely because they had a more complex function than direct bone formation.

Histological analysis of the newly formed mineralized tissue was used to understand the observed robust bone morphogenesis. Endochondral ossification occurred, despite the absence of any deliberate induction toward the chondrogenic lineage and despite the implantation on a calcium phosphate scaffold recently shown to induce intermembraneous ossification by hESC-MCs prepared by an alternate protocol.32 The implanted cells presumably received cues from both the hypoxic bone defect environment and the collagen/hydroxyapatite scaffold they were implanted on that guided them, in situ, along an endochondral ossification process, as evidenced by the hallmark presence of hypertrophic chondrocytes, highly vascularized mineralized tissue (Fig. 3), and osteogenic and chondrogenic protein production (Figs. 3 and 5 and collagen II staining shown in Supplementary Fig. S2). The endochondral pathway has been previously put forward as a preferred developmental engineering pathway for enhanced bone regeneration by adult hMSCs29 and mouse ESC-progenitors.30 In endochondral ossification, optimal conditions for bone formation are established in situ by the developing cartilage itself, which could be considered as a self-designed scaffold that is simultaneously osteoinductive, angiogenic, and supports the survival of the implanted cells.31 However, previous experiments with ESCs that promoted the endochondral pathway prior to implantation and attempted cranial defect healing have not been successful. Only 8–10% bony fill with concomitant formation of a variety of other tissue types including undesirable teratomas was previously observed.30 Our results are contrary to a recent study that reported that endochondral ossification by hESC-MCs, precultured on a scaffold in osteogenic medium and then implanted in a subcutaneous implantation site, was associated with the least bone formation.32 The positive results in this study are attributed to the deliberate lack of preculturing in osteogenic medium on a scaffold and allowing for the in situ cues from host calvarial site to dominate and guide the cells to a successful outcome. Importantly, despite the simple protocol used in the present study, there was no evidence of any residual undifferentiated hESCs by flow cytometry or teratoma formation. Longer term implantation studies of hESC-MCs derived with this same protocol have further verified the lack of teratoma formation.51

Evidence for the direct participation of the hESC-MCs in the formation of the new bone tissue in the present study was rigorously demonstrated by localization of human-specific Alu sequences in cells embedded within and surrounding histologically verified neobone tissue (Fig. 3), and the localization of a human bone-associated protein in the matrix surrounding the human-derived cells (Fig. 5). Thorough proof of human bone-associated protein production and the finding of human cells adjacent to AP-positive stained areas adjacent to active mineralization areas (AC+) by the implanted human cells was a crucial observation in these studies. Typical decalcified paraffin studies were augmented by nondecalcified cryohistological studies that, for the first time, demonstrated active participation of implanted hESC-MC within the active mineralization fronts. It was uncertain whether this would be the outcome because it has been reported that host rather than donor progenitor cell activity dominates the repair process during MSC donor studies, particularly at the periphery of the defect.54 MSC implantation studies that have focused on identifying the fate and active role of host versus donor cells have found only a low percentage of donor cells present in the tissue regeneration site, with mainly host cells in the functional role of secreting extracellular matrix and producing the new tissue.40,55 The hESC-MCs used in the present study were a more effective cell therapeutic than the adult MSCs in the mouse calvarial defect site since they could directly form mineralized tissue and not rely on host cell induction, migration, and osteogenic activity.

These results may potentially represent that adult bone marrow-MSCs are an adult tissue resident stem cell whose normal function is small-scale tissue repair to maintain homeostasis and its own self-renewal. When extracted and cultured, adult bone marrow-MSCs will have a higher tissue specific gene expression because of their developmental lineage in that tissue. However, this also potentially limits their capacity for large-scale tissue regeneration, perhaps because of inherent functionality or even limited proliferation. In contrast, the hESC-MC are directly differentiated from a pluripotent source and although testing indicates the hESC-MC can function similar to a MSC, because it has not been influenced by any specific tissue niche, it may really be a less specific progenitor and thus have reduced tissue specific gene expression. When the cells are placed within the correct (i.e., bone defect) environment, they are triggered to complete a developmental process that enables large-scale tissue regeneration. The advantage of using hESC for tissue regeneration may thus be summed up as, adult hMSCs from bone marrow are capable of tissue repair, while hESC-MC are capable of induced developmental tissue generation.

The high efficiency and simplicity of this progenitor derivation process together with the robust participation of the hESC-MCs in the bone regeneration process demonstrates that progenitors from hESCs can overcome many previously stated cell-therapy hurdles. While ethical and immunological rejection concerns may prevent the use of hESC-MCs in humans, the characteristics of the hESC-MCs derived by the Boyd et al.33 protocol should be further studied and used as a template for the development of cell lines for therapeutic use. In a broader context, these results imply that developmental engineering approaches applied to multipotent cells may simplify the role of the tissue engineer and be a simple and effective means to produce progenitor cells that can repair bone semi-autonomously after in vivo implantation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from the Connecticut Stem Cell program, assistance from the University of Connecticut stem cell core directed by RenHe Zhu and Douglas Adams for VIVACT imaging.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Bruder S.P., Kurth A.A., Shea M., Hayes W.C., Jaiswal N., and Kadiyala S.Bone regeneration by implantation of purified, culture-expanded human mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res 16, 155, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming J.E., Jr., Cornell C.N., and Muschler G.F.Bone cells and matrices in orthopedic tissue engineering. Orthop Clin N Am 31, 357, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chanda D., Kumar S., and Ponnazhagan S.Therapeutic potential of adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in diseases of the skeleton. J Cell Biochem 111, 249, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abumaree M., Al Jumah M., Pace R.A., and Kalionis B.Immunosuppressive properties of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Rev 8, 375, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuomo A.V., Virk M., Petrigliano F., Morgan E.F., and Lieberman J.R.Mesenchymal stem cell concentration and bone repair: potential pitfalls from bench to bedside. J Bone Joint Surg 91, 1073, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meijer G.J., de Bruijn J.D., Koole R., and van Blitterswijk C.A.Cell-based bone tissue engineering. PLoS Med 4, e9, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siddappa R., Licht R., van Blitterswijk C., and de Boer J.Donor variation and loss of multipotency during in vitro expansion of human mesenchymal stem cells for bone tissue engineering. J Orthop Res 25, 1029, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gamradt S.C., and Lieberman J.R.Genetic modification of stem cells to enhance bone repair. Ann Biomed Eng 32, 136, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarugaser R., Lickorish D., Baksh D., Hosseini M.M., and Davies J.E.Human umbilical cord perivascular (HUCPV) cells: a source of mesenchymal progenitors. Stem Cells 23, 220, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baba K., Yamazaki Y., Ishiguro M., Kumazawa K., Aoyagi K., Ikemoto S., et al.Osteogenic potential of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells cultured with umbilical cord blood-derived fibrin: a preliminary study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg pii: , 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu G., Li Y., Sun J., Zhou H., Zhang W., Cui L., et al.In vitro and in vivo evaluation of osteogenesis of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells on partially demineralized bone matrix. Tissue Eng Part A 16, 971, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barberi T., Willis L.M., Socci N.D., and Studer L.Derivation of multipotent mesenchymal precursors from human embryonic stem cells. PLoS Med 2, e161, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carpenter M.K., Rosler E., and Rao M.S.Characterization and differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Cloning Stem Cells 5, 79, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomson J.A., Itskovitz-Eldor J., Shapiro S.S., Waknitz M.A., Swiergiel J.J., Marshall V.S., et al.Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science 282, 1145, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trounson A.Human embryonic stem cells: mother of all cell and tissue types. Reprod Biomed Online 4Suppl 1, 58, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arpornmaeklong P., Brown S.E., Wang Z., and Krebsbach P.H.Phenotypic characterization, osteoblastic differentiation, and bone regeneration capacity of human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 18, 955, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bielby R.C., Boccaccini A.R., Polak J.M., and Buttery L.D.In vitro differentiation and in vivo mineralization of osteogenic cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng 10, 1518, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Both S.K., van Apeldoorn A.A., Jukes J.M., Englund M.C., Hyllner J., van Blitterswijk C.A., et al.Differential bone-forming capacity of osteogenic cells from either embryonic stem cells or bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 5, 180, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harkness L., Mahmood A., Ditzel N., Abdallah B.M., Nygaard J.V., and Kassem M.Selective isolation and differentiation of a stromal population of human embryonic stem cells with osteogenic potential. Bone 48, 231, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang N.S., Varghese S., Lee H.J., Zhang Z., Ye Z., Bae J., et al.In vivo commitment and functional tissue regeneration using human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 20641, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S., Kim S.S., Lee S.H., Eun Ahn S., Gwak S.J., Song J.H., et al.In vivo bone formation from human embryonic stem cell-derived osteogenic cells in poly(d,l-lactic-co-glycolic acid)/hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds. Biomaterials 29, 1043, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kopher R.A., Penchev V.R., Islam M.S., Hill K.L., Khosla S., and Kaufman D.S.Human embryonic stem cell-derived CD34+ cells function as MSC progenitor cells. Bone 47, 718, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuznetsov S.A., Cherman N., and Robey P.G.In vivo bone formation by progeny of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 20, 269, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marolt D., Campos I.M., Bhumiratana S., Koren A., Petridis P., Zhang G., et al.Engineering bone tissue from human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 8705, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Undale A., Fraser D., Hefferan T., Kopher R.A., Herrick J., Evans G.L., et al.Induction of fracture repair by mesenchymal cells derived from human embryonic stem cells or bone marrow. J Orthop Res 29, 1804, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arpornmaeklong P., Wang Z., Pressler M.J., Brown S.E., and Krebsbach P.H.Expansion and characterization of human embryonic stem cell-derived osteoblast-like cells. Cell Reprogram 12, 377, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gawlitta D., Farrell E., Malda J., Creemers L.B., Alblas J., and Dhert W.J.Modulating endochondral ossification of multipotent stromal cells for bone regeneration. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 16, 385, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliveira S.M., Mijares D.Q., Turner G., Amaral I.F., Barbosa M.A., and Teixeira C.C.Engineering endochondral bone: in vivo studies. Tissue Eng Part A 15, 635, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scotti C., Tonnarelli B., Papadimitropoulos A., Scherberich A., Schaeren S., Schauerte A., et al.Recapitulation of endochondral bone formation using human adult mesenchymal stem cells as a paradigm for developmental engineering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 7251, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jukes J.M., Both S.K., Leusink A., Sterk L.M., van Blitterswijk C.A., and de Boer J.Endochondral bone tissue engineering using embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 6840, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lenas P., Moos M., and Luyten F.P.Developmental engineering: a new paradigm for the design and manufacturing of cell-based products. Part I: from three-dimensional cell growth to biomimetics of in vivo development. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 15, 381, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang N.S., Varghese S., Lee J.H., Zhang Z., and Elisseeff J.Biomaterials directed in vivo osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A 19, 1723, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyd N.L., Robbins K.R., Dhara S.K., West F.D., and Stice S.L.Human embryonic stem cell-derived mesoderm-like epithelium transitions to mesenchymal progenitor cells. Tissue Eng Part A 15, 1897, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuhn L.T., Liu Y., Advincula M., Wang Y.H., Maye P., and Goldberg A.J.A nondestructive method for evaluating in vitro osteoblast differentiation on biomaterials using osteoblast-specific fluorescence. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 16, 1357, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neen D., Noyes D., Shaw M., Gwilym S., Fairlie N., and Birch N.Healos and bone marrow aspirate used for lumbar spine fusion: a case controlled study comparing healos with autograft. Spine 31, E636, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gang E.J., Bosnakovski D., Figueiredo C.A., Visser J.W., and Perlingeiro R.C.SSEA-4 identifies mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow. Blood 109, 1743, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riekstina U., Cakstina I., Parfejevs V., Hoogduijn M., Jankovskis G., Muiznieks I., et al.Embryonic stem cell marker expression pattern in human mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, heart and dermis. Stem Cell Rev 5, 378, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boskey A.L., and Roy R.Cell culture systems for studies of bone and tooth mineralization. Chem Rev 108, 4716, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siggelkow H., Rebenstorff K., Kurre W., Niedhart C., Engel I., Schulz H., et al.Development of the osteoblast phenotype in primary human osteoblasts in culture: comparison with rat calvarial cells in osteoblast differentiation. J Cell Biochem 75, 22, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rai B., Lin J.L., Lim Z.X., Guldberg R.E., Hutmacher D.W., and Cool S.M.Differences between in vitro viability and differentiation and in vivo bone-forming efficacy of human mesenchymal stem cells cultured on PCL-TCP scaffolds. Biomaterials 31, 7960, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levi B., Nelson E.R., Li S., James A.W., Hyun J.S., Montoro D.T., et al.Dura mater stimulates human adipose-derived stromal cells to undergo bone formation in mouse calvarial defects. Stem Cells 29, 1241, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bianco P., Fisher L.W., Young M.F., Termine J.D., and Robey P.G.Expression of bone sialoprotein (BSP) in developing human tissues. Calcifi Tissue Int 49, 421, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gerstenfeld L.C., and Shapiro F.D.Expression of bone-specific genes by hypertrophic chondrocytes: implication of the complex functions of the hypertrophic chondrocyte during endochondral bone development. J Cell Biochem 62, 1, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leboy P.S., Vaias L., Uschmann B., Golub E., Adams S.L., and Pacifici M.Ascorbic acid induces alkaline phosphatase, type X collagen, and calcium deposition in cultured chick chondrocytes. J Biol Chem 264, 17281, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cooper L.F., Harris C.T., Bruder S.P., Kowalski R., and Kadiyala S.Incipient analysis of mesenchymal stem-cell-derived osteogenesis. J Dental Res 80, 314, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tremoleda J.L., Forsyth N.R., Khan N.S., Wojtacha D., Christodoulou I., Tye B.J., et al.Bone tissue formation from human embryonic stem cells in vivo. Cloning Stem Cells 10, 119, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arinzeh T.L., Tran T., McAlary J., and Daculsi G.A comparative study of biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics for human mesenchymal stem-cell-induced bone formation. Biomaterials 26, 3631, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haynesworth S.E., Goshima J., Goldberg V.M., and Caplan A.I.Characterization of cells with osteogenic potential from human marrow. Bone 13, 81, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krebsbach P.H., Kuznetsov S.A., Satomura K., Emmons R.V., Rowe D.W., and Robey P.G.Bone formation in vivo: comparison of osteogenesis by transplanted mouse and human marrow stromal fibroblasts. Transplantation 63, 1059, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lonza Walkersville I.Clonetics™ Endothelial Cell Medium Products. www.lonza.com #CC-26-8, 2011

- 51.Boyd N.L., Nunes S.S., Jokinen J.D., Krishnan L., Chen Y., Smith K.H., et al.Microvascular mural cell functionality of human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal cells. Tissue Eng Part A 17, 1537, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boyd N.L., Nunes S.S., Krishnan L., Jokinen J.D., Ramakrishnan V.M., Bugg A.R., et al.Dissecting the role of human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal cells in human umbilical vein endothelial cell network stabilization in three-dimensional environments. Tissue Eng Part A 19, 211, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cruess R.L., and Dumont J.Healing of Bone, Tendon, and Ligament. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott, 1975 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tortelli F., Tasso R., Loiacono F., and Cancedda R.The development of tissue-engineered bone of different origin through endochondral and intramembranous ossification following the implantation of mesenchymal stem cells and osteoblasts in a murine model. Biomaterials 31, 242, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Horwitz E.M., and Prather W.R.Cytokines as the major mechanism of mesenchymal stem cell clinical activity: expanding the spectrum of cell therapy. Isr Med Assoc J 11, 209, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.