Abstract

Background:

There is limited data on the prevalence of impulse control disorder and related behaviors (ICD-RBs) in Indian patients with Parkinson's Disease (PD). In the context of potential genetic and environmental factors affecting the expression of ICD-RBs, studying other multiethnic populations may bring in-sights into the mechanisms of these disorders.

Objectives:

To ascertain point prevalence estimate of ICD-RBs in Indian PD patients, using the validated “Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive Disorders in Parkinson's disease (QUIP)” and to examine their association with Dopamine replacement therapy (DRT).

Materials and Methods:

This was a hospital based observational cross-sectional study. After taking informed consent, patients and their informants (spouse, or primary caregiver) were made to complete the QUIP, and were instructed to answer questions based on behaviors that occurred anytime during PD that lasted at least four consecutive weeks.

Results:

Total of 299 patients participated in the study. At least one ICD-RB was present in 128 (42.8%), at least one Impulse control disorder (ICD) was present in 74 (24.75%) and at least one Impulse control related compulsive behaviour (ICRB) was present in 93 (31.1%) patients. Punding was the most frequent (12.4%) followed by hyper sexuality (11.04%), compulsive hobbyism (9.4%), compulsive shopping (8.4%), compulsive medication use (7.7%), compulsive eating (5.35%), walkabout (4%) and pathological gambling (3.3%). ≥ 2 ICD-RBs were observed in 15.7% of patients. After multivariate analysis, younger age of onset, being unmarried were specifically associated with presence of ICD. Longer disease duration was specifically associated with presence of ICRB. Whereas smoking and higher dopamine levodopa equivalent daily doses (DA LEDD) were associated with both presence of ICD and ICRB. Higher LD LEDD was specifically associated with presence of ICD-RB.

Conclusions:

Our study revealed a relatively higher frequency of ICD-RBs, probably because of the use of screening instrument and because we combined both ICDs and ICRBs. Also high proportion of DA use (81.6%) among our patients might be responsible. The role of genetic factors that might increase the risk of developing ICD-RBs in this population needs further exploration.

Keywords: Impulse control disorders, impulse control disorder related compulsive behaviour disorders, Parkinson's disease, QUIP

Introduction

The term impulse control disorder and related behaviors (ICD-RBs), defines a group of complex behavioral disorders characterized by failure to resist an impulse or temptation to perform an act that is harmful to the individual or to others.[1]

Throughout the past decade it has been recognized that dopaminergic medications administered to remedy motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease (PD) are associated with an enhanced risk for impulse control disorders and related compulsive behaviors (ICD-RBs) such as hobbyism, punding, and the dopamine dysregulation syndrome (DDS). These complications are relatively frequent, affecting 6-15.5% of patients, and they most often appear, or worsen, after initiation of dopaminergic therapy or dosage increase.[2] Besides a high dose of dopamine (DA) agonists, additional risk factors associated with ICD-RBs in PD include young age at PD onset (often in early forties), male gender, a novelty seeking personality, depression, a personal or family history of addictive behaviors, and genetic factors.[2]

ICD-RBs are under-recognized in clinical practice. Most patients do not spontaneously offer information about ICD-RBs, either because of shame or because they do not understand that it is related to PD and its treatment. Early detection of ICD-RBs is crucial and all patients should be questioned directly about such behavior. A useful tool to detect ICD-RBs can be the Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive Disorders in Parkinson's disease (QUIP), a validated quick screening questionnaire that when positive should be followed by a clinical directed interview.[3]

In the context of potential genetic and environmental factors affecting the expression of ICD-RBs, studying other multiethnic populations may bring insights into the mechanisms of these disorders. Thus, in the present study, we investigated the prevalence of ICD-RBs in Indian PD patients on dopamine replacement therapy (DRT) and the possible risk factors associated with these conditions.

Aims and objectives

To Ascertain point prevalence estimate of Impulse control disorders and related behaviours (ICD-RBs) in Indian PD patients, using the QUIP.

To examine the association of ICD-RBs with DRT.

Materials and Methods

This was a hospital based observational cross-sectional study conducted in Department of Neurology, AIIMS at New Delhi, India over a period of 15 months from March, 2012 to May, 2013. Convenience sample of patients with Idiopathic PD attending neurology clinic during their regular outpatient visits were considered for inclusion in the study. The study was approved by ethics committee of the institute. 299 patients were included in study (fulfilling inclusion and exclusion criteria).

Inclusion criteria

Patients with Idiopathic PD (Diagnosis was made according to the United Kingdom Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank Criteria).

Age: 30-75 yrs.

On treatment with dopamine replacement therapy for more than 1 year with documented response and whose treatment was not modified based on prior reporting of ICD-RBs.

Exclusion criteria

Patient not consenting for study.

Cognitive abnormality (mini-mental state examination, MMSE <24) that might interfere with the understanding of questionnaire.

Assessment procedure

All participants were informed that the primary purpose of the study was to examine the frequency of ICD-RBs in PD and their association with PD medications.

After taking informed consent, patients and their informants (spouse, or primary caregiver) were made to complete the QUIP, and were instructed to answer questions based on behaviors that occurred anytime during PD that lasted at least 4 consecutive weeks.

The QUIP is a screening instrument with high discriminant validity for ICD-RBs in PD, and covers a comprehensive range of impulsive-compulsive behaviours occurring at any time since PD onset and lasting 4 weeks. The questionnaires were administered in the subjects’ language of choice.

The QUIP has three sections: Section 1 assesses four ICDs (involving gambling, sexual, buying, and eating behaviors) with five questions (including an introductory question that defines and gives examples of problem behaviours), Section 2 assesses other compulsive behaviors (punding, hobbyism, and walkabout) with three distinct introductory questions and two common additional questions, and Section 3 assesses compulsive medication use with five questions (including an introductory question).

Based on the results of the validation of the QUIP[3], the following cut-offs were used to represent a positive screen: compulsive gambling (any 2 of the 5 items); compulsive sexual behavior (any 1 of the 5 items); compulsive buying (any 1 of the 5 items); compulsive eating (any 2 of the 5 items); Other compulsive behaviors (Hobbysim: item 1A, Punding: Item 1B, Walkabouts: item 1C); Compulsive medication use (item 1 and 4).

The following demographic and clinical variables were recorded in predesigned Performa: age, sex, age at onset, duration of disease subject's history and family history of psychiatric disorders, gambling and substance abuse, the Unifying Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) motor score in the “on” state, Modified Hoehn and Yahr scale (H and Y) score in the “on” state, complete details of antiparkinsonian therapy, LEDD of all individual drugs was noted and levodopa (LD), dopamine (DA) as well as total levodopa equivalent daily doses (LEDD) were calculated. The recorded PD medications and dosages were those being taken at the time of assessment.

LEDD in milligrams was calculated according to the conversion factors of individual antiparkinsonian drugs.[4] In brief, conversion factors were: immediate release levodopa (LD) × 1, Controlled release LD × 0.75, entacapone: LD × 0.33 (irrespective of entacapone dose it is the L-dopa dose that is multiplied by 0.33 to give subtotal LED for entacapone), Tolcapone; LD × 0.5, Duodopa; × 1.11, Pramipexole (as salt); × 100, Ropinirole; × 20, Rotigotine: × 30, Selegiline-Oral; × 10, Selegiline-sublingual; × 80, Rasagiline; × 100, Amantadine; × 1, Apomorphine; × 10.

LD LEDD, DA LEDD and total LEDD were divided into tertiles to examine dosing effects (LD, > 0- ≤ 250 mg, > 250-≤ 400 mg, > 400 mg; DA LEDD, > 0-≤150 mg, > 151-≤ 300 mg, > 300, total LEDD, > 0-≤400 mg, > 400-≤ 800 mg, > 800 mg).

Statistical analysis

Sample size of 300 patients was calculated to allow prevalence estimation of ICD-RBs with 3% precision, assuming prevalence estimate of up to 15%. In addition this sample size would be enough for detection of odds ratio of 2.5 or more when analysing factors related to ICD-RBs.

Data was entered into an electronic database for statistical analysis (SPSS, version 20.0). Data was presented as number (%) or mean (SD) as appropriate Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test and continuous variables using Student's t-test for independent samples. Variables with a possible (P < 0.1) association with ICD-RBs on bivariate analysis were included in a multivariate logistic regression model, examining for independent predictors of ICD-RB as a binary dependent variable. The results were reported as OR (95% CI). The P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Description of study population

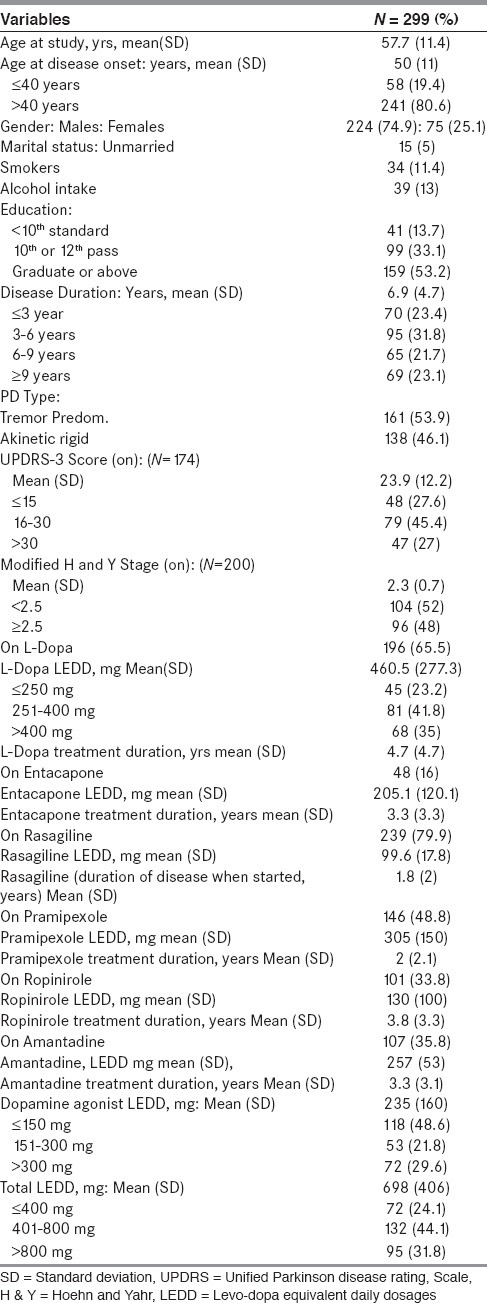

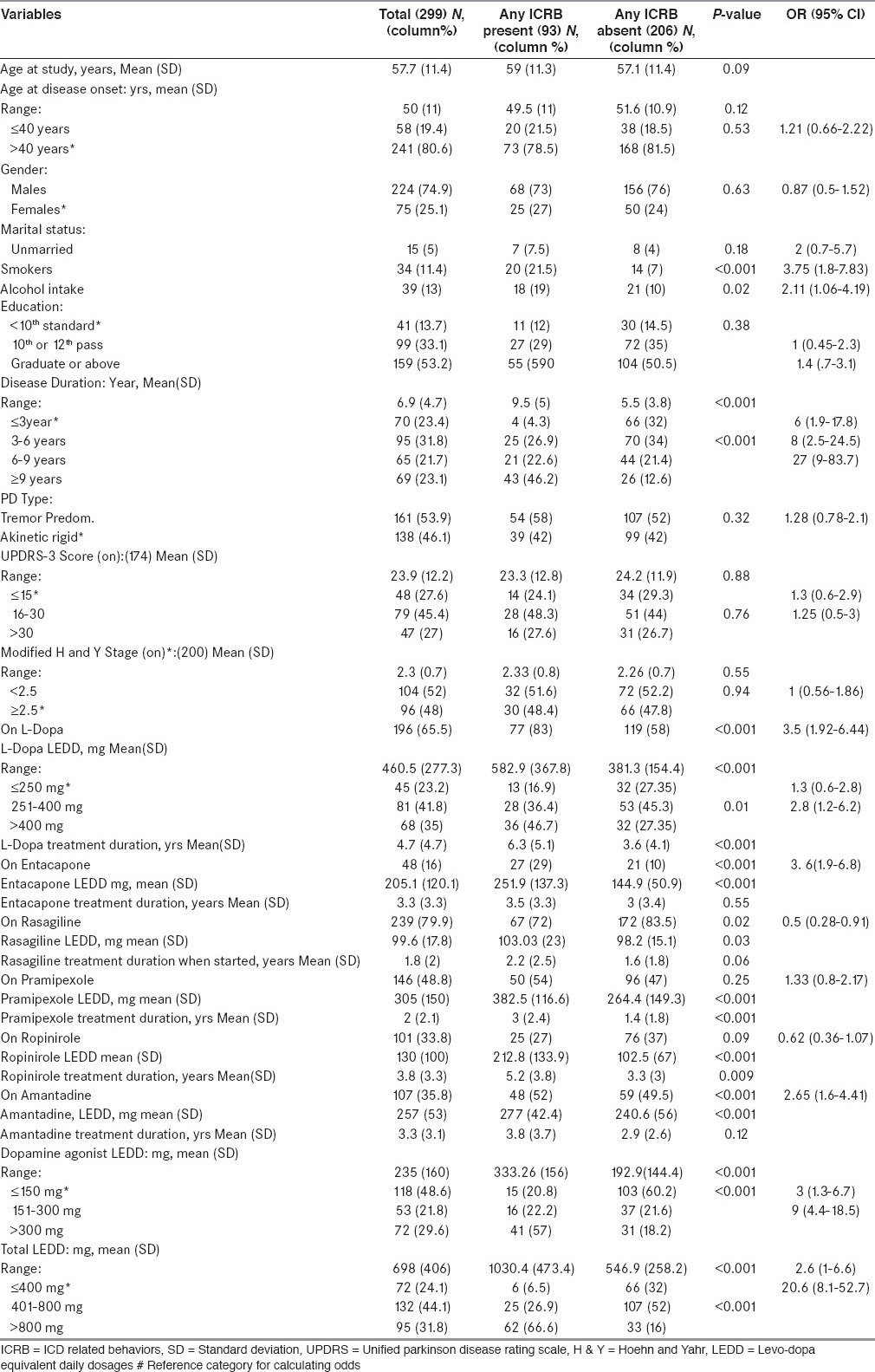

Total 299 patients participated in the study. Almost all patients, N = 296 (98.9%) were taking either LD or DA. Majority of patients, N = 245 (81.9%) were on DA, 100 patients (33.4%) were on DA monotherapy. 146 patients (50.3%) were on pramipexole and 101 patients (34.8%) were on ropinirole. 196 patients (65.5%) were on LD, 51 patients (17.1%) were on LD monotherapy. 145 patients (48.5%) were on both LD and DA. The mean (SD) LEDD, mg for LD was 460.5 (277.3), for DA: 235 (160), for pramipexole: 305 (150) and for ropinirole: 130 (100). The mean (SD) total LEED, mg was 698 (406). Note is made of marked difference in mean LEDD of pramipexole and ropinirole [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and treatment characteristics of all study subjects

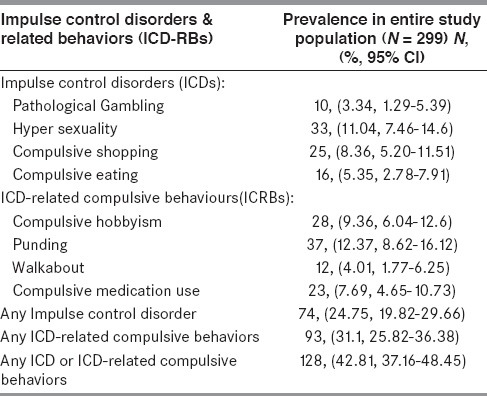

Prevalence of Impulse control disorders and related behaviors

At least one ICD-RB was present in 128 (42.8%), at least one ICD was present in 74 (24.75%) and at least one ICRB was present in 93 (31.1%) patients. Punding was the most frequent (12.4%) followed by hyper sexuality (11.04%), compulsive hobbyism (9.4%), compulsive shopping (8.4%), compulsive medication use (7.7%), compulsive eating (5.35%), walkabout (4%) and pathological gambling (3.3%). ≥ 2 ICD-RBs were observed in 15.7% of patients. The frequency of ICD-RBs in subjects exposed only to LD (20.3%) was lower than in those on DA agonists monotherapy (24.2%), which in turn was lower than in those exposed to both LD and DA agonists (55.5%) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Prevalence of Impulse control disorders and related behaviors

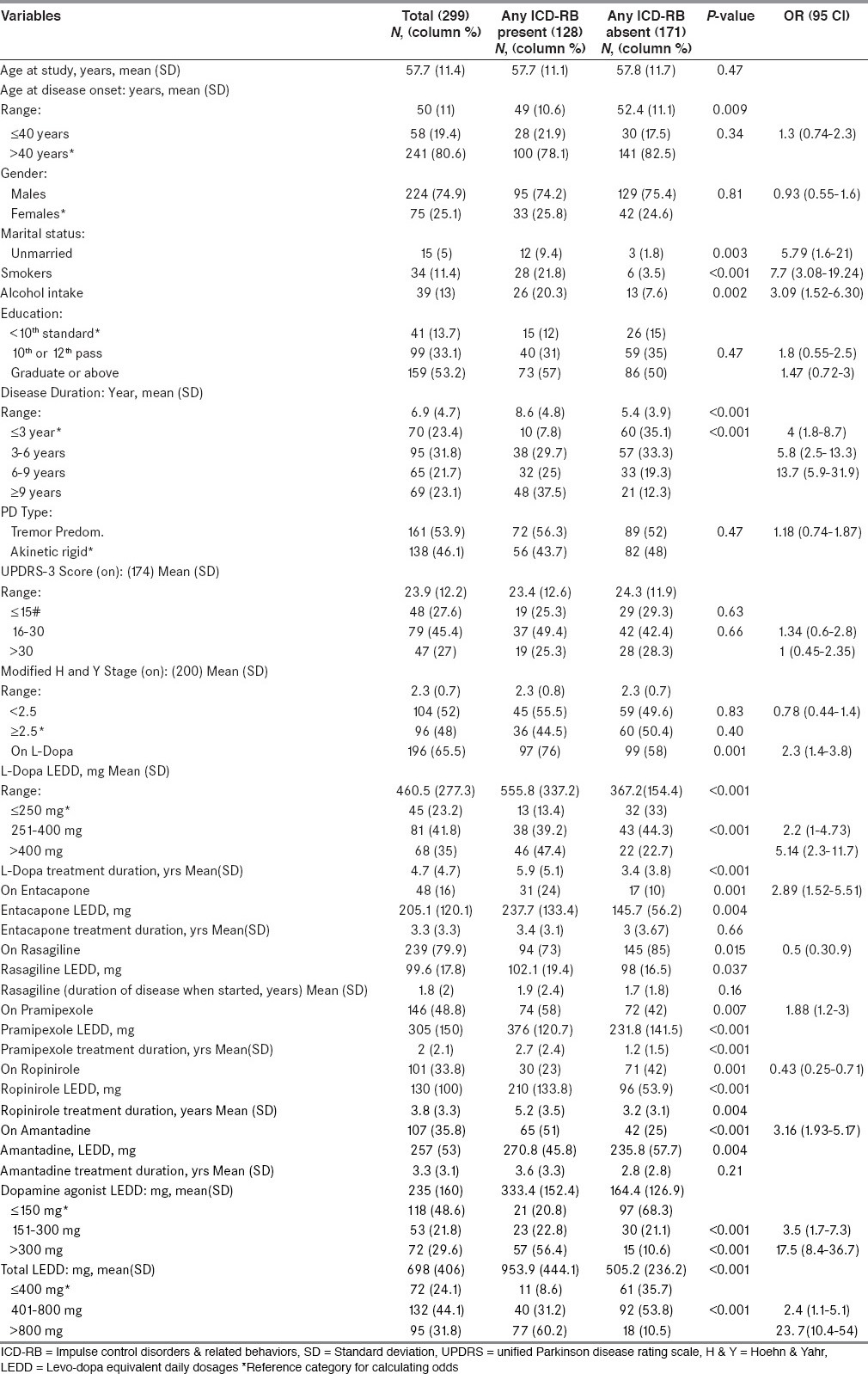

Demographic, clinical & treatment characteristics of subgroups on basis of presence or absence of ICD-RBs

As per bivariate analysis, compared with patients without ICD-RBs, those with ICD-RBs had younger age at disease onset, were more likely to be unmarried, smokers, taking alcohol, having longer disease duration. Regarding treatment characteristics: Patients taking LD, DA, entacapone and amantadine had a higher frequency of ICD-RBs. Also, compared with patients without ICD-RBs, those with ICD-RBs were on higher dose and longer treatment duration of LD and DA [Table 3].

Table 3.

Demographic, clinical and treatment characteristics of all study subjects and of subgroups on basis of presence or absence of ICD-RBs

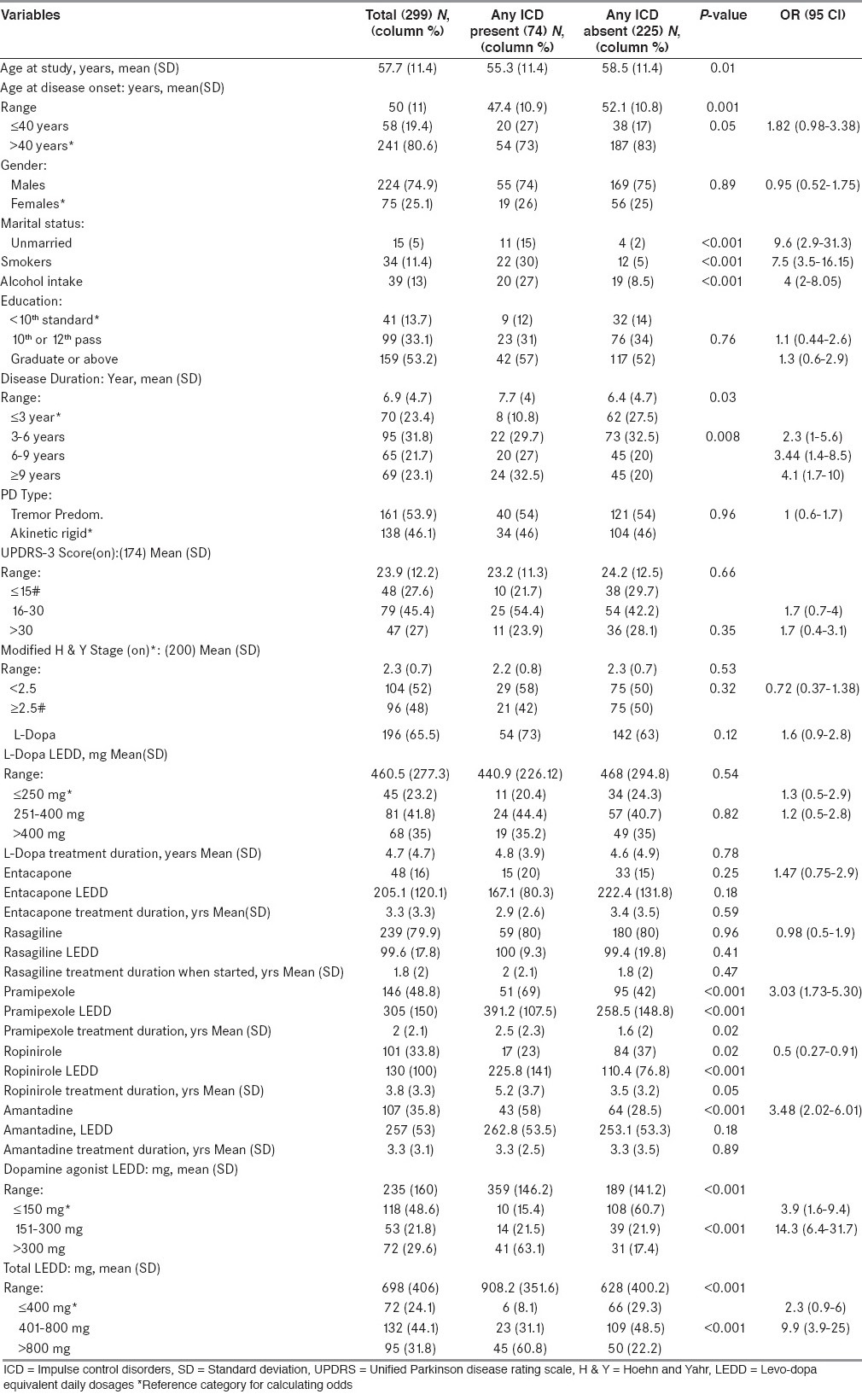

Demographic, clinical & treatment characteristics of subgroups on basis of presence or absence of ICDs

As per bivariate analysis, compared with patients without ICDs, those with ICDs had younger age at time study and at disease onset, were more likely to be unmarried, smokers, taking alcohol, having longer disease duration. Regarding treatment characteristics: patients taking DA and amantadine had a higher frequency of ICDs. Also, compared with patients without ICDs, those with ICDs were on higher dose and longer treatment duration of DA [Table 4].

Table 4.

Demographic, clinical and treatment characteristics of all study subjects and of subgroups on basis of presence or absence of ICDs

Demographic, clinical and treatment characteristics of subgroups on basis of presence or absence of ICRBs

As per bivariate analysis, compared with patients without ICRBs, those with ICRBs were more likely to be smokers, taking alcohol, having longer disease duration. Regarding treatment characteristics: patients taking LD, entacapone and amantadine had a higher frequency of ICRBs. Also, compared with patients without ICRBs, those with ICRBs were on higher dose and longer treatment duration of LD and DA [Table 5].

Table 5.

Demographic, clinical and treatment characteristics of all study subjects and of subgroups on basis of presence or absence of ICRBs

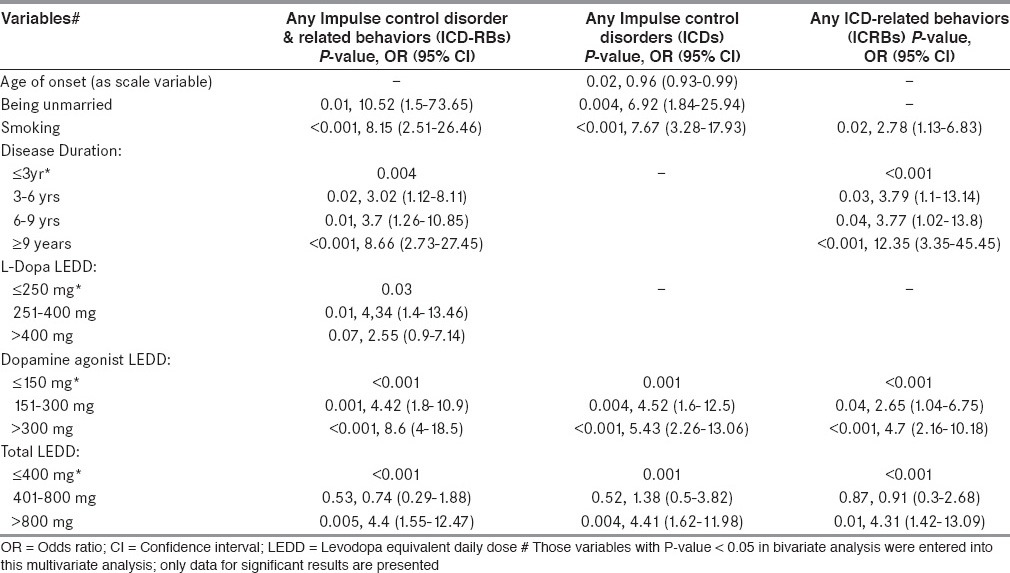

Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis examining predictors of presence of Impulse control disorder & related behaviours in entire study population

Examining entire study population, demographic, clinical and treatment variables associated with presence of any ICD-RB on multivariate analysis were being unmarried, smoking, longer disease duration & higher LD, DA and total LEDD. Those associated with presence of any ICDs on multivariate analysis were younger age of onset, being unmarried, smoking and higher DA and total LEDD. Those associated with presence of any ICRB on multivariate analysis were smoking, longer disease duration & higher DA and total LEDD [Table 6].

Table 6.

Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis examining predictors of presence of Impulse control disorder and related behaviours in entire study population

In other words after multivariate analysis, younger age of onset and being unmarried were specifically associated with presence of any ICD. Longer disease duration was specifically associated with presence of any ICRB. Whereas smoking and higher DA LEDD were associated with both presence of ICD and ICRB. Higher LD LEDD was specifically associated with presence of any ICD-RB.

Discussion

Nearly 44% of our patients screened positive on the QUIP for symptoms of at least one ICD-RB. However, the 62% positive predictive value of the QUIP (when measured against a gold standard of diagnostic interview using formal criteria)[3,5] suggests that some cases screening positive likely would not have fulfilled formal diagnostic criteria. On the positive side, the QUIP was utilized because no other instrument for ICD-RBs fulfils the criteria of being both comprehensive and validated for use in PD. As a screening instrument, the QUIP has very high sensitivity and negative predictive values of 96-100%.[3,5] Identification of ICD-RBs at subsyndromal levels is still important, with implications on patient monitoring and therapeutic decisions-as such patients may be at elevated risk of developing ICD-RBs in the future. Assuming a true positive rate of 40-50%[3,5], this would still yield an ICD-RB prevalence of around 20%, which is comparable to findings in Western PD populations.[6,7,8]

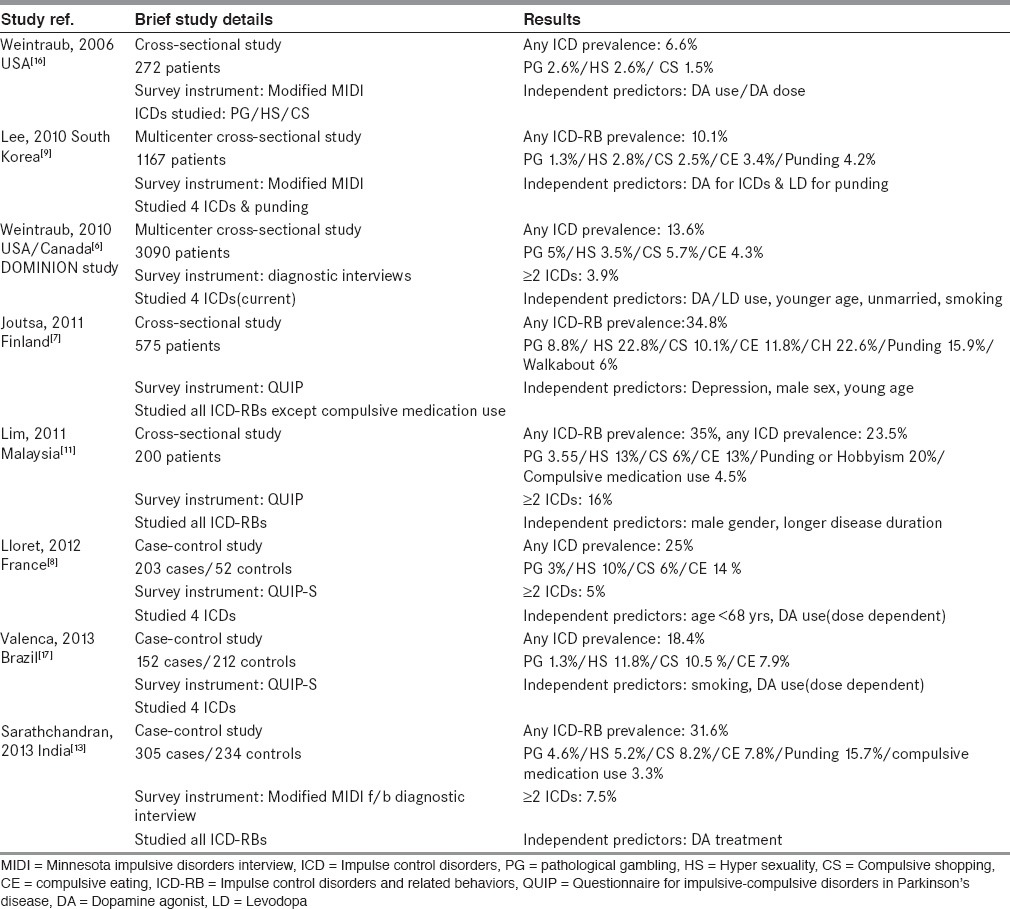

Analyzing individual ICD-RBs separately & combined as groups (ICD-RBs, ICDs and ICRBs), prevalence numbers vary. A few Asian studies have reported varying frequencies between 3.5% and 35%.[9,10,11] Cultural and social factors may influence these results, as the specific behaviour depends on patient access to the particular habit. Many studies have estimated the prevalence of pathological gambling between 1.3 and 9.3%.[6,9,12] Perhaps this explains our low prevalence of pathological gambling (3.3%), since in our country gambling is illegal. Conversely, punding and compulsive hobbyism were more prevalent in our study: 12.4% and 9.4% respectively which is similar to another recently published Indian study.[13] Concerning Hyper sexuality, compulsive shopping and eating, we estimated the prevalence in 11.4%, 8.4% and 5.35% respectively, while in a large cohort these were estimated at 35%, 5.7% and 4.3%.[6]

Our study revealed a relatively higher frequency of ICD-RBs, probably because of the use of screening instrument and because we combined both ICDs and ICRBs. Also high proportion of DA use (81.6%) among our patients might be responsible. The role of genetic factors that might increase the risk of developing ICD-RBs in this population needs further exploration.

In our study, the frequency of ICD-RBs in subjects exposed only to LD was lower than in those on DA agonists monotherapy, which in turn was lower than in those exposed to both LD and DA agonists. This finding is in line with previous findings.[6]

Furthermore, the results of our bivariate analysis into associated factors are consistent with other studies.[2,6,11,12,14,15] Bivariate analysis in our study showed that ICD-RBs are associated with younger age, being unmarried, smoking, alcohol intake, longer disease duration, use and higher dose of amantadine, use/higher dose/longer treatment duration of DA and LD.[2]

Regarding the independent predictors of ICD-RBs after multivariate analysis in our study: demographic, clinical and treatment variables associated with presence of any ICD-RB were being unmarried, smoking, longer disease duration and higher LD, DA and total LEDD. Those associated with presence of any ICDs were younger age of onset, being unmarried, smoking and higher DA and total LEDD. Those associated with presence of any ICRB were smoking, longer disease duration and higher DA and total LEDD. In other words, younger age of onset and being unmarried were specifically associated with presence of any ICD. Longer disease duration was specifically associated with presence of any ICRB. Whereas smoking and higher DA LEDD were associated with both presence of ICD and ICRB. Higher LD LEDD was specifically associated with presence of any ICD-RB.

The most relevant finding of our study was that ICDs subgroup was different from ICRBs subgroup in terms of association with demographic, clinical and treatment variables. Younger age of disease onset and being unmarried were specifically associated with ICDs group. Whereas longer disease duration was specifically associated with ICRBs group. Similar observation has been described previously.[9]

Similarly to others,[2] our results showed that DA agonists are the most important predictor for ICD-RBs. We observed that subjects manifesting ICD-RBs symptoms were exposed to significantly higher doses of DA agonists, which is in line with empirical experience, indicating that dose reductions may help manage these behaviours.

Summary of previous studies relevant in context of our study are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Summary of previous studies relevant in context of our study

However, it should be noted that direct comparisons of ICD-RBs prevalence among different studies is not justified for following reasons: 1) difference in survey instruments used; some have used screening instruments, some have used diagnostic interviews and others have used both. 2) Varying number of behaviours included under broad heading of ICD-RBs: Some have studied individual behaviours, some have studied ICDs only and others have studied ICDs along with varying number of ICRBs. 3) Some have studied current (active) ICD-RBs that is, within last 6 months only whereas others have studied their presence anytime during PD. Hence different studies are likely to report varying prevalence. Only studies which are similar in all three above mentioned aspects can be compared.

The main limitation of this study was the subsequent lack of characterization of QUIP-positive patients with regards to the presence of ICD-RBs according to formal diagnostic criteria. However, it should be noted that this questionnaire proved to have good clinimetric properties, with sensitivity and specificity values between 85-100% for all explored ICD-RBs and the data here contribute further to the understanding of the properties of this assessment tool. This study was confined to a single center; this factor potentially limits the generalizability of our results. Lack of inclusion of an early untreated PD group and a non-PD control group prevents comparison of prevalence estimates for ICD-RBs in untreated and treated PD patients and the general population.

The sample size was calculated to detect factors strongly related to ICDs (that is, odds ratios >2.5), but the power of the study was insufficient to detect milder correlations. Also, our sample size did not allow for detailing predictors of each type of ICD-RBs, but only for ICD-RB, ICD and ICRB as a groups.

Additionally, this survey was centred on pharmacological factors potentially related to ICD-RBs, whereas others, such as psychiatric and cognitive impairments or familial ICD history, have not been explored.

To summarize, our results suggest that DA replacement therapy in PD patients predisposes to the occurrence of ICD-RBs, converging to those found in literature.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Source Information [Internet] [Last accessed 2013 Aug 28]. Available from: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/sourcereleasedocs/current/DSM4 .

- 2.Callesen MB, Scheel-Krüger J, Kringelbach ML, Møller A. A systematic review of impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2013;3:105–38. doi: 10.3233/JPD-120165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weintraub D, Hoops S, Shea JA, Lyons KE, Pahwa R, Driver-Dunckley ED, et al. Validation of the questionnaire for impulsive-compulsive disorders in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24:1461–7. doi: 10.1002/mds.22571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomlinson CL, Stowe R, Patel S, Rick C, Gray R, Clarke CE. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2649–53. doi: 10.1002/mds.23429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papay K, Mamikonyan E, Siderowf AD, Duda JE, Lyons KE, Pahwa R, et al. Patient versus informant reporting of ICD symptoms in Parkinson's disease using the QUIP: Validity and variability. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17:153–5. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weintraub D, Koester J, Potenza MN, Siderowf AD, Stacy M, Voon V, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: A cross-sectional study of 3090 patients. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:589–95. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joutsa J, Martikainen K, Vahlberg T, Voon V, Kaasinen V. Impulse control disorders and depression in Finnish patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18:155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perez-Lloret S, Rey MV, Fabre N, Ory F, Spampinato U, Brefel-Courbon C, et al. Prevalence and pharmacological factors associated with impulse-control disorder symptoms in patients with Parkinson disease. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2012;35:261–5. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e31826e6e6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JY, Kim JM, Kim JW, Cho J, Lee WY, Kim HJ, et al. Association between the dose of dopaminergic medication and the behavioral disturbances in Parkinson disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16:202–7. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auyeung M, Tsoi TH, Tang WK, Cheung CM, Lee CN, Li R, et al. Impulse control disorders in Chinese Parkinson's disease patients: The effect of ergot derived dopamine agonist. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17:635–7. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim SY, Tan ZK, Ngam PI, Lor TL, Mohamed H, Schee JP, et al. Impulsive-compulsive behaviors are common in Asian Parkinson's disease patients: Assessment using the QUIP. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17:761–4. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallagher DA, O’Sullivan SS, Evans AH, Lees AJ, Schrag A. Pathological gambling in Parkinson's disease: Risk factors and differences from dopamine dysregulation. An analysis of published case series. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1757–63. doi: 10.1002/mds.21611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarathchandran P, Soman S, Sarma G, Krishnan S, Kishore A. Impulse control disorders and related behaviors in Indian patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2013;28:1901–2. doi: 10.1002/mds.25557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voon V, Fernagut PO, Wickens J, Baunez C, Rodriguez M, Pavon N, et al. Chronic dopaminergic stimulation in Parkinson's disease: From dyskinesias to impulse control disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1140–9. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70287-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim SY, Evans AH, Miyasaki JM. Impulse control and related disorders in Parkinson's disease: Review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1142:85–107. doi: 10.1196/annals.1444.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weintraub D, Siderowf AD, Potenza MN, Goveas J, Morales KH, Duda JE, et al. Association of dopamine agonist use with impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:969–73. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.7.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valença GT, Glass PG, Negreiros NN, Duarte MB, Ventura LM, Mueller M, et al. Past smoking and current dopamine agonist use show an independent and dose-dependent association with impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19:698–700. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]