Abstract

In hybrid search, observers memorize a number of possible targets and then search for any of these in visual arrays of items. Wolfe (2012) has previously shown that reaction times in hybrid search increase with the log of the memory set size. What enables this logarithmic search of memory? One possibility is a series of steps in which subsets of the memory set are compared to all items in the visual set simultaneously. In the current experiments, we presented single visual items sequentially in a Rapid Serial Visual Presentation (RSVP) display, eliminating the possibility of simultaneous testing of all items. We used a staircasing procedure to estimate the time necessary to effectively detect the target in the RSVP stream. Processing time increased in a loglinear fashion with number of potential targets. This eliminates the class of models that requires simultaneous comparison of some memory items to all (or many) items in the visual display. Experiment Three shows memory search efficiency is influenced by similarity between the target set and the distractors in the RSVP stream as it is in visual search. These results indicate that observers perform separate memory searches on each eligible item in the visual display. Moreover, it appears that memory search for one item can proceed while other items are being categorized as “eligible” or not.

Keywords: attention, memory, visual search, visual attention, categorization

INTRODUCTION

In the majority of studies of visual search, observers (Os) search for a single type of target that may or may not be present amongst distractor items (Chan & Hayward, 2012; Wolfe, 2012). However, in the real world, we frequently search for one of many possible targets in the same image. Thus, baggage screeners might search for liquids, knives and guns and radiologists search for bone fractures, cancerous tumors, blood clots and so forth. Searching for items in the real world is often a, ”hybrid search” through a memory set and the visual display.

In order to study hybrid search, Wolfe (2012) parametrically varied both the visual set size and the memory set size in a visual search experiment. Unsurprisingly, the search task becomes more difficult when the number of possible items increases: searching for apples, peppers, avocados and cherries is more difficult than searching for just apples. However, the cost of searching through additional items in memory seems to be qualitatively different than searching through additional items in visual space (Wolfe, 2012). In visual search, the cost of additional items in the display is typically roughly linear. In the Wolfe (2012) experiment, each additional item cost about 15ms when observers (Os) were searching for a single target. In contrast, in search through a memory set, RTs increased linearly with the log of the memory set size with each log2 item costing about 56ms when there was a single item in the visual array (Wolfe, 2012).

What is the source of this logarithmic relationship? Such relationships occur when a constant proportion of possible options can be discarded on each step of a process. Thus, the average number of guesses required to guess a number between 1 and N is log2(N) if you ask questions of the form: Is it less than N/2? N/4, etc. Perhaps Hybrid search proceeds by asking “Is anything in the visual display like these N/2 similar items in memory?” Attention could be guided on the basis of similarity to subsets of the memory set in something akin to this 20-questions game.

Alternatively, a visual item might be matched against all items in the memory set at the same time. Recognition memory can be modeled as an accumulation of evidence toward a decision boundary (Ratcliff 1978; Leite and Ratcliff 2010; Ratcliff and Starns 2013). The decision bound needs to be placed far enough from the start of the information accumulation so that false alarm errors are prevented. The bound needs to be near enough to the start to avoid wasting time or committing miss errors. A hybrid search decision about whether this visual item is one of N possible items in memory can be implemented as N accumulators, operating in parallel. The chances of a false alarm error increase given N opportunities to go over a decision bound by mistake. It would be prudent, therefore, to raise the decision bound. The amount that the bound needs to be raised while holding error rates constant leads to a pattern of RTs that increases apparently logarithmically with the number of items.

There are various other ways to model the basic hybrid data. The present study is an effort to constrain the space of plausible models by presenting the visual subset over time in a Rapid Serial Visual Presentation (RSVP) mode. We wondered whether the log search through memory is specific to situations in which all potential targets are simultaneously available to the observer. Consider the first model, sketched above: It proposes a form of “guided” search in which subsets of the memory set define the guidance: Are there any red items, are there any circular items, and so forth.

If this process of spatial guidance based on memory set attributes is critical the observed loglinear search through memory space, then forcing the items to be considered independently should result in much less efficient search through memory space. Thus, we presented visual items, one after the other, in RSVP: distributing the items across time rather than space. Since we observe the same logarithmic relationship of memory set size to RT (here measured as a threshold RSVP rate), we can eliminate this class of models.

Previous work has shown that increasing the number of possible target items results in increased difficulty correctly noting the presence of a target item in RSVP (Akyurek, Abedian-Amiri, & Ostermeier, 2011; Akyurek & Hommel, 2005; Akyurek, Hommel, & Jolicoeur, 2007; Shapiro, Raymond, & Arnell, 1994). These demonstrations were observed in attentional blink experiments. In this paradigm, a number of items are displayed in an RSVP stream while the observer searches the stream for Target One (T1) and Target 2 (T2). Detection of the T1 leads to impaired performance on T2 when it follows within roughly 500ms (Raymond, Shapiro, & Arnell, 1992; Shapiro et al., 1994).

Recently, Akyurek and colleagues (2007) showed that increasing the number of possible T1 items led to a larger impairment on T2 detection. More importantly, for current purposes, the authors observed a large cost on T1 accuracy and speed as the number of possible T1 items increased from 1 to 4 items. The authors describe the decrease in accuracy as ‘fairly linear’. However, without going to higher sets sizes it is very difficult to determine whether the function is actually linear or loglinear. A similar issue can be seen in the early work on hybrid visual X memory searches. When small numbers of alphanumeric characters were held in memory, visual search for any member of those small sets also looked essentially linear (Schneider & Shiffrin, 1977; Wickens, Moody, & Dow, 1981). It was only with the larger set sizes that the relationship was revealed to be logarithmic (Burrows & Okada, 1975; Wolfe, 2012).

As Akyurek and colleagues were interested in role of working memory (WM) in the attentional blink, their T1 items changed prior to each trial. Given that WM is generally estimated to be ~3–4 items (Cowan, 2001; Luck & Vogel, 1997), it would be very difficult to increase the WM load high enough to confidently distinguish between linear and loglinear memory search. Sternberg (1966) faced a similar problem in some of the initial memory scanning studies. These studies typically involve learning list of words: a task where it is difficult to hold more than 10 items without extensive practice. In the current study, we were able to avoid this issue by asking observers to search for unique objects held in “activated long term memory (ALTM - Cowan, 1995) rather than WM. As the picture and object recognition literature has shown, with unique objects, observers can quickly encode up 100s or even 1000s of items in ALTM without much difficulty (Brady, Konkle, Alvarez, & Oliva, 2008; Standing, 1973).

The general approach for this paper is to extend the spatial hybrid search findings to a RSVP paradigm that emphasizes sequential processing of individual items. Though previous work had suggested that memory search follows a linear function when the visual items are members of an RSVP stream, we suspect that this may be due to the relatively small memory set size manipulations in those experiments. In Experiments 1 & 2, we present converging evidence that hybrid search remains logarithmic when the items are presented sequentially. In the final experiment, we extended this work by showing that although memory search appears to be logarithmic, the efficiency of this search is strongly modulated by target-distractor similarity in a manner similar to what is observed in the visual search literature.

Experiment 1: Estimating Processing Time in Hybrid Search

Methods

Observers

41 observers (Os) between 18 and 54 years of age gave informed consent and were paid $10/hr to participate in the 3 experiments. There were 14 observers in Experiment 1, 13 in Experiment 2 and 14 in Experiment 3 (mean age Experiment 1: 30, Experiment 2: 35, Experiment 3: 27). All had at least 20/25 vision with correction, all passed the Ishihara Color Test, and all were fluent speakers and readers of English. One observer was excluded from Experiment 1 because s/he never reached a stable threshold in the set size 100 block of the experiment, generating an estimate that was 7 standard deviations higher than any of the other observers in that condition. One observer was excluded from Experiment 2 after repeatedly not being able to successfully pass the 100-memory item test.

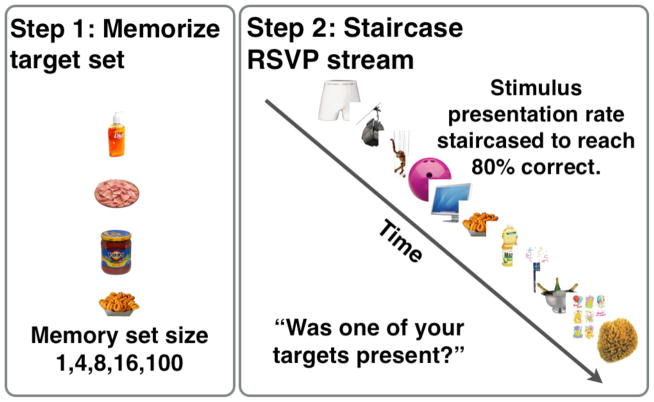

Procedure

In all three experiments, observers were asked to complete a similar task. In part one of each block of the experiment, observers were asked to memorize between 2–100 target objects. Order of the memory blocks was randomized across Observers. All objects were taken from a heterogenous set of 3000 unique photorealistic objects provided by Brady et al., (2008). Experimental Sessions were carried out on a Macintosh G4 computer running Mac OS 10.5. Experiments were written in Matlab 7.5 (The Mathworks) using the Psychophysics Toolbox (Brainard, 1997; Pelli, 1997), version 3. Stimuli were presented on 20″ CRT monitor (Mitsubishi Diamond Pro 91TXM) with resolution set to 1280 × 960 pixels, and an 85 Hz refresh rate. Observers were placed so that their eyes were 57.4 cm from the monitor. At this distance, each object was centered in a virtual square that subtended 2.7 degrees visual angle. Actual size of the object varied, but was never smaller than 1.5 DVA on the long axis.

Following Wolfe (2012), observers were taught their target objects by displaying each object from the target set individually at the center of the screen for 3 seconds. After this brief encoding, we tested observers to ensure that the target set was effectively in memory. For the memory test, we presented individual objects at the center of the screen and asked whether each object was part of the target set. Half of the items were from the target set and the others were drawn from the larger set of objects. This yields a total of 2X trials for each memory test, where X represents the size of the memory set. If accuracy was below 90%, the observer viewed the learning phase once more before being tested again. Once the memory test was passed twice, the observer was allowed to proceed to the second part of the experiment.

In the second part of each block of the experiment, observers viewed Rapid Serial Visual Presentations (RSVP) of 16 objects presented at the center of the screen. At the end of each trial, the observer was asked whether the RSVP stream contained an object from the target set. Half of the trials contained a single target item that occurred randomly between position 4 and 14 in the stream. Each block was preceded by 12 practice trials. When the target set was 100 items (in Experiments 1 & 2), observers completed 240 trials in this part of the experiment. Otherwise, this part of the experiment contained 180 trials. Observers were asked to complete additional trials in when the target set was 100 items because, in pilot testing, we found that our threshold estimation procedure did not stabilize within 180 trials for all observers when the target set was 100. During the experimental block of trials, we manipulated stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA) for each objects using an interlaced staircasing procedure. At the start of the experimental block, SOA was set to 15ms per object for one stream and 200ms for the other. We employed a 3 up, 1 down staircase with a fixed step size that targeted 79.4% correct (García-Pérez, 1998). The initially slow and initially fast staircases were randomly interlaced. This reduces the ability of observer to anticipate the rate on the next trial based on the answer to the current trial.

Results & Discussion

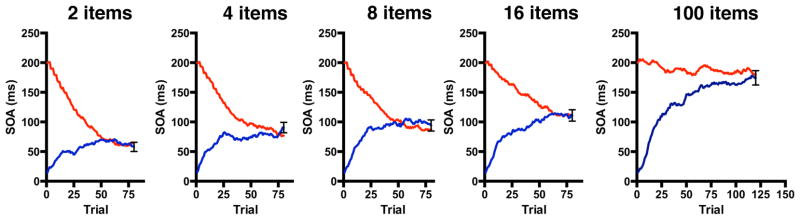

Figure 2 shows the staircase data averaged across from each block of the experiment. It is clear that the interleaved staircase procedure worked: the two staircases converge for each memory set size by the end of the block. It is also clear that the final RSVP rate asymptote varies as a function of the memory set size. To estimate processing time, we used QUEST to estimate the final threshold based on the observed performance (King-Smith, Grigsby, Vingrys, Benes, & Supowit, 1994; Watson & Pelli, 1983). QUEST is an adaptive psychometric procedure that uses Bayes’ theorem to estimate a posterior probability function given the current data, which is treated as the prior. While QUEST is often used to determine the stimulus intensity (stimulus duration in this case) for each trial, here we used QUEST in to analyze the previously gathered data and generate a final threshold estimate for each individual for each block. To ensure that we had we enough observations near the threshold for reliable estimates, we set the parameters of the QUEST algorithm to predict the SOA threshold for 79.4% correct performance. We find qualitatively similar results if we analyze all of the inflection points or if we average SOA over the final 30 trials of each block.

Figure 2.

Average results for initially slow (red) and initially fast (blue) RSVP staircases in Experiment One. Error bars represent standard error of the mean at the end of each block.

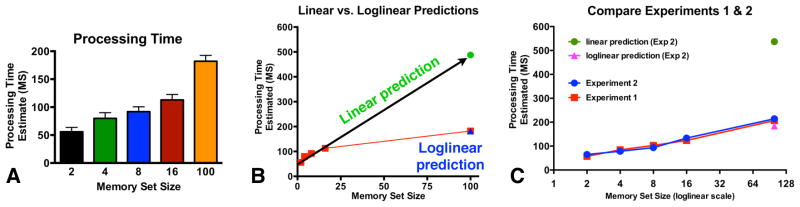

Figure 3a shows mean processing time as a function of memory set size in Experiment 1. Memory set size had a strong effect on processing time (F(4, 48)=57.35, p<.001, generalized eta2=.64), which increased from 57ms for memory set size 2 to 207ms for memory set size 100. To evaluate whether the slope of this function followed a linear or loglinear function, we used the data from memory set sizes 2–16 to predict performance on set size 100. As shown in Figure 3b, the loglinear prediction for set size 100 did not differ from the observed data significantly (161ms vs 182 ms: t(12)=1.81, p=.09), while the linear prediction (422 ms) was far higher than observed value (t(12)=4.61, p<.001).

Figure 3.

A) QUEST-estimated processing time to correctly identify 79.4% of all trials for each memory set size. B) Predicted processing time for set size 100 based on a linear extrapolation from memory set sizes 2–16 (Green Circle) or from an extrapolation from log2(memory set size) (Black triangle). Clearly the logarithmic prediction is closer to the data. C) Estimated processing time for Experiments 1 & 2. Again, the logarithmic prediction is much closer to the data. Error bars here, and throughout the paper represent standard error of the mean. Errors bars are encompassed by the data points in Figure 3C.

Experiment 2: Forcing sequential processing in the RSVP hybrid search task

The results of Experiment 1 strongly suggest that search through memory occurs in a loglinear fashion even when the items are presented in an RSVP stream. However, although each item was presented sequentially, it is possible that the items were not processed sequentially1. Perhaps potential target items were temporarily stored in memory, and a decision was made once each of these items had been compared to the target memory set. Along similar lines, rather than identifying any single target item, our observers might have made their decision at the end of each trial based on the amount of ‘target-like’ evidence that accumulated over the sequence of item. Perhaps the observed evidence in favor of loglinear search through memory is a result of allowing observers to search through a memory space offline, at the end of each trial. If this is the case, then requiring speeded online responses should result in a memory search that is less efficient, perhaps forcing a linear search through potential target items.

Method

Unless otherwise stated, Experiment 2 was identical to Experiment 1. The only difference between the two experiments was the response method. Observers were instructed to respond as soon as they saw an object from their target set in the RSVP stream. Responses that occurred more than 2.5 seconds after the offset of the target item or prior to the onset of the target were coded as incorrect responses and observers were encouraged to try to respond more quickly. Less than 1% of trials were marked as incorrect for this reason.

Results & Discussion

As can be seen in Figure 3c, the results from Experiment 2 are essentially identical to those of Experiment 1. As in Experiment 1, we found a significant effect of memory set size on estimated processing time (F(4,44)=57.66, p<.001, generalized eta2=.73) increasing from 64ms in set size 2, to 214ms in set size 100. Our data again suggest that the time for search through memory was a logarithmic function of set size and not a linear function. The linear estimate based on memory set sizes 2:16 (537ms) was significantly higher than the observed data (t(11)=5.85, p<.001), while the loglinear prediction (185ms) was again not significantly different than observed data (t(11)=1.82, p=.09). In fact, when we directly compare the two experiments, while there was a large main effect for memory set size (F(4,92)=114.1, p<.001, generalized eta2=.68), there was no effect of Experiment and the two factors did not interact (both p’s>.1, generalized eta2 <.04).

Our results indicate that pushing observers to process each object online, as soon as it was presented, had no effect on the ability to complete the task. This is strong evidence against the idea that groups of possible target objects were processed offline, after they were initially displayed. Note that this does not mean that each item was processed to completion before the next one appeared. The RSVP rates, especially for the smaller target set sizes, are inconsistent with estimates of the minimum “dwell time” required to fully process an item in an RSVP stream (Ward, Duncan et al. 1996; Egeth and Yantis 1997). The threshold RSVP durations reflect the rate at which items can enter and leave a processing pipeline. There may be multiple items in the pipeline at one time (Moore and Wolfe 2001; Wolfe 2003).

Experiment 3: Searching within and between categories

In spatial visual search, the efficiency of search is driven by both target-distractor similarity and distractor-distractor similarity (Duncan & Humphreys, 1989). In visual search for a single target, observers tend to search through only those items that share at least one feature with the target object (Egeth, Virzi, & Garbart, 1984; Wolfe, Cave, & Franzel, 1989; Zohary & Hochstein, 1989). Observers can avoid wasting time on items that are never going to be targets.

The situation is somewhat different in the temporal search domain. In spatial visual search, items lacking the correct visual features are simply never selected in the course of the search. In RSVP, however, the items are presented to the spatial locus of fixation. We may assume that attention is directed to each object in turn, with little effective preattentive filtering. Nevertheless, it seems obvious that the relationship of the non-target items to the items in the memory set will still influence the rate at which items can be presented in a hybrid RSVP search task. Suppose that the memory set consists of 4 red items (apple, red car, cherry and ball). It seems intuitively clear that the RSVP rate would be faster if all non-target items were green than if all non-target items were red. In this case, however, any benefit would seem to arise from a rapid process of identification and dismissal of irrelevant non-targets.

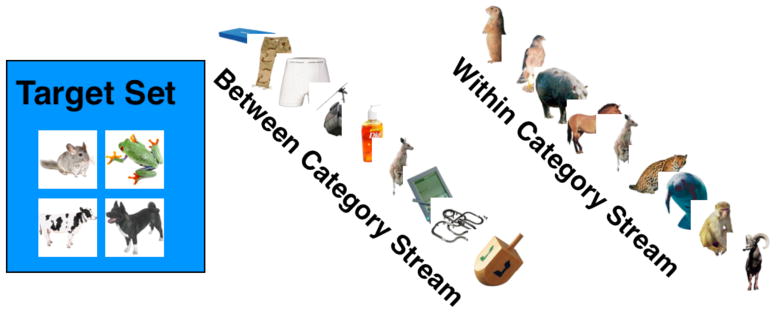

To test this hypothesis, we divided our object set into 223 animal items and 2129 non-animal items. In this experiment, all target items were drawn from the animal set. We then tested the ability to detect one of these animal targets in two types of RSVP streams. Either each item was an animal (within category condition) or all but one item was a non-animal (between category condition). In the between category condition, the one animal item that was presented was drawn from the target set on 50% of trials.

Method

Except where otherwise noted, the procedure for this experiment was identical to Experiment 1. Observers completed 4 blocks of trials in a randomized order. Prior to the threshold estimating procedure used previously, 2,4,8 or 16 target items memorized and tested following the same procedure as in the previous experiments. In the previous experiments, there were two interlaced staircases for a single condition. In Experiment 3, the two experimental conditions, between- and within-category, were interlaced in a single block. Each block contained 10 practice trials followed by 200 experimental trials. Again, we used a 3-up, 1-down staircase that guided performance towards 79.4% correct. SOA was set to 115ms for both conditions at the start of each block. Processing time was estimated using the previously described QUEST procedure.

For the within-category condition, all 16 items in the RSVP stream, including the target, when present, were drawn from the animal object set. For the between-category condition, 15 of the 16 items were drawn from the non-animal object set. One item in every between-category stream was an animal. This animal item was a target animal on 50% of trials (otherwise, the task could be accomplished trivially by monitoring the stream for any animal).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

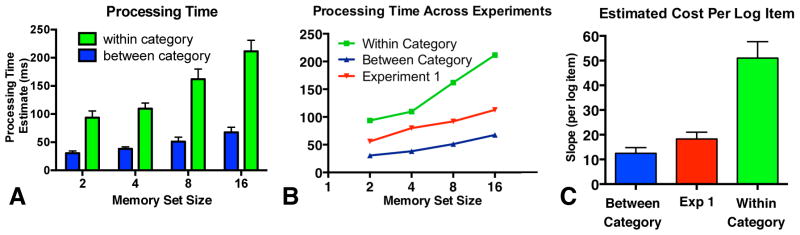

As in Experiments 1 & 2 estimated processing time increased with memory set size in both the between (F(3,39)=13.14, p<.001, generalized eta2=.26) and within-category conditions (F(3,39)=40.78, p<.01, generalized eta2=.41; see Figure 5a). Furthermore, search through memory appears to be better fit by loglinear model than by a linear model (note that the axes in Figure 5 are logarithmic).

Figure 5. Results for Experiment Three with comparison to Experiment One.

A) Estimated processing time for within and between category streams as a function of memory set size. B) Estimated processing time for the two conditions in Experiment 3 as compared to data from Experiment 1. Note that data is plotted on a loglinear scale. C) The slope of the estimated processing time for Experiments 1 & 3. Slope here is an indication of the cost in ms of searching through an additional log2 item.

Figure 5 shows that there was a strong effect of RSVP stream type (F(1,13)=113.9, p<.001, generalized eta2=.57) and target set size (F(1,13)=37.15, p<.001, generalized eta2=.34) on estimated processing time. These factors interacted significantly (F(3,39)=27.98, p<.001, generalized eta2=.13). To better understand the interaction, we analyzed the change in processing time as a function of target size. This estimate of slope can be thought of as a measure of the cost of each additional log2 item in memory on processing time. As can been seen in Figure 5c, the slope was significantly higher in the within-category RSVP stream when Os had to decide whether each animal in the visual stream was one of the memory set animals (F(1,13)=47.79, p<.001, generalized eta2=.53). In the between category case, it seems clear that Os could quickly determine that an item was categorically a non-target without having to perform a memory search through the set of possible targets.

Figure 5 also shows that the rate of search through memory in Experiment 1 (22 ms/log item) falls between the rate observed in the two conditions in Experiment 3. This is what might be expected based on the visual search literature. In Experiment 1, both targets and distractors were drawn from the complete, heterogeneous set of objects. Thus, a specific visual item would be unlikely to be rejected on the basis of its categorical status. This makes Experiment 1 harder than the between-category condition. At the same time, Experiment 1 is easier than the within-category condition because the target and distractor items are not as similar to each other. We have emphasized the role of semantic categories in influencing the rate of search through memory in this experiment. It is worth remembering that items in our ‘animal’ category are also more similar to one another than to items in the ‘nonanimal’ category in terms of their basic visual features and that this will also modulate search times (Duncan & Humphreys, 1989). If we return to the multiple accumulator model sketched in the introduction to this paper, we can imagine that the decision bounds need to be set quite high when we ask, “Is this animal one of the 10 animals in my memory set?” The chances of a false alarm in this case would be higher than when we ask, “Is this object one of the 10 objects in my very diverse memory set?”

The results of Experiment 2 suggested that requiring Observers to respond to target presence does not influence the rate of search through memory when the target is embedded in a stream of heterogenous objects. However, we wondered whether the results of Experiment 3 might have been influenced by the ability to hold a single animal item in memory then conduct a memory search once the trial had concluded. If Observers engaged in this strategy, there should be a strong relationship between response time and memory set size for the between category trials. On those trials, Os could hold an animal in memory and do the memory search at the end of the trial. Our data does not support this prediction: There was no effect of memory set size on RT for between category trials (F(3,52)=0.5, p=.71).

GENERAL DISCUSSION

In Wolfe’s (2012) data on combined visual and memory search, RT was a linear function of the visual set size but rose linearly with the log of the memory set size. In a standard visual search, with all items present on the screen, there is a class of models that could explain the result by proposing that some number of items in the memory set were being simultaneously matched to some or all of the items in visual set. For instance, the observed loglinear function could be the consequence of breaking the memory set into sub-groups and then completing the search for each sub-group in turn. Degree of feature overlap (for example) might inform which sub-group of memory items was searched first. The present study rules out this class of theory by presenting items in an RSVP stream, thereby forcing items to be processed in series, though it remains possible that a small number of visual items would be processed at the same time in a pipeline fashion.

Experiment Three provides the clearest evidence that the memory search for one possible target item does not need to be completed before the next visual item appears (or is attended, in the spatial visual search case). When all the items in the RSVP stream are animals, a memory search is needed for every (or almost every) item in order to determine if the animal is one of the animals in the memory set. The resulting RSVP rate that can be supported is relatively slow, < 5Hz when memory set size is 16. When all but one of the visual items are non-animals, presumably many fewer visual items provoke a memory search and the rate is much faster, ~15 Hz when memory set size is 16. Note, however, that there is a single animal in the RSVP stream in this latter condition of Experiment 3. That item needs to be checked against the memory set. If that memory search needed to reach the same state as reached by each item in the all animal, within-category condition, then the single animal should be a rate-limiting step in the one animal, between-category condition, then the two conditions would have produced approximately the same result in RSVP because that single memory search would be a rate-limiting step. Instead, the data show that the items can be presented much more quickly in the between-category stream. Unless the memory search becomes about 3X faster in the between-category case, this suggests that the memory search for an animal in position N can continue after the appearance of the next several items in RSVP.

This pattern of data is consistent with two-stage models of the attentional blink (Chun and Potter 1995) and with Botella’s model of illusory conjunctions in RSVP word lists (Botella, Suero et al. 2001). Both models propose high-capacity first stages that initially evaluate all items. Items that exceed a target threshold are sent to a limited capacity second stage. Errors are typically attributed to situations where the second stage is processing a non-target when the target occurs. In this scheme, increasing the similarity of the distractor items increases the likelihood of an item that appears similar to the target. This, in turn, leads to more errors because of the increased likelihood that the second stage will be occupied when the target appears.

Conclusions

While the mechanisms that underlie this memory search are still very much in question, as a consequence of the loglinear search, observers were able to effectively determine whether a single object was one of 100 potential targets in memory when that target object is visible for less than 200ms despite strong forward and backward masking. Based on the Wolfe (2012) data, we can estimate that a visual search for a single target amongst 100 visual items from this set of objects would take ~1500ms. This represents converging evidence that search through memory is more efficient than search through visual space, and this difference accelerates at higher set sizes. This is important because while it may sometimes seem as though we have to search through many visual items (i.e. locations in a room) to find our target (i.e. car keys), it pales in comparison to the massive amount of information stored in memory that we must search through to find answers to mundane questions like “Who sings this song?” or “Who’s car is that?” In both of these examples, there is a single stimulus to compare against a huge amount of information held in long-term memory. As in the temporal search task employed in the current set of experiments, spatial guidance based on target-set features is not useful in the evaluation of this single item. The data presented here suggest we are to be able to answer these questions in a timely manner via a loglinear search through memory that is capable of evaluating multiple items simultaneously.

Figure One.

Schematic illustration of the methods

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of conditions for Experiment Three

Footnotes

We thank Karen Arnell for this idea.

Contributor Information

Trafton Drew, Email: Tdrew1@rics.bwh.harvard.edu, Visual Attention Lab, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Cambridge, MA, U.S.A.

Jeremy M. Wolfe, Email: wolfe@search.bwh.harvard.edu, Visual Attention Lab, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Cambridge, MA, U.S.A

References

- Akyurek EG, Hommel B. Short-term memory and the attentional blink: capacity versus content. Mem Cognit. 2005;33(4):654–663. doi: 10.3758/bf03195332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akyurek EG, Abedian-Amiri A, Ostermeier SM. Content-specific working memory modulation of the attentional blink. Plos One. 2011;6(2):e16696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akyurek EG, Hommel B, Jolicoeur P. Direct evidence for a role of working memory in the attentional blink. Mem Cognit. 2007;35(4):621–627. doi: 10.3758/bf03193300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botella J, Suero M, et al. A model of the formation of illusory conjunctions in the time domain. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 2001;27(6):1452–1467. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.27.6.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady TF, Konkle T, Alvarez GA, Oliva A. Visual long-term memory has a massive storage capacity for object details. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(38):14325–14329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803390105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard DH. The psychophysics toolbox. Spatial Vision. 1997;10(4):433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows D, Okada R. Memory retrieval from long and short lists. Science. 1975 doi: 10.1126/science.188.4192.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan LK, Hayward WG. Dimension-specific signal modulation in visual search: evidence from inter-stimulus surround suppression. J Vis. 2012;12(4):10. doi: 10.1167/12.4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun MM, Potter MC. A two-stage model for multiple target detection in rapid serial visual presentation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1995;21:109–127. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.21.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N. Attention and Memory: An integrated framework. New York: Oxford U press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N. The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2001;24:87–185. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x01003922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan J, Humphreys G. Visual search and stimulus similarity. Psychological Review. 1989;96:433–458. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.96.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeth HE, Yantis S. Visual Attention: Control, representation, and time course. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:269–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeth HE, Virzi RA, Garbart H. Searching for conjunctively defined targets. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 1984;10(1):32–39. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.10.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Pérez MA. Forced-choice staircases with fixed step sizes: asymptotic and small-sample properties. Vision Research. 1998;38(12):1861–1881. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(97)00340-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintzman DL, Caulton DA, Levitin DJ. Retrieval dynamics in recognition and list discrimination: further evidence of separate processes of familiarity and recall. Mem Cognit. 1998;26(3):449–462. doi: 10.3758/bf03201155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King-Smith PE, Grigsby SS, Vingrys AJ, Benes SC, Supowit A. Efficient and unbiased modifications of the QUEST threshold method: Theory, simulations, experimental evaluation and practical implementation. Vision Research. 1994;34(7):885–912. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite FP, Ratcliff R. Modeling reaction time and accuracy of multiple-alternative decisions. Atten Percept Psychophys. 2010;72(1):246–273. doi: 10.3758/APP.72.1.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ, Vogel EK. The capacity of visual working memory for features and conjunctions. Nature. 1997;390:279–281. doi: 10.1038/36846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CM, Wolfe JM. Getting beyond the serial/parallel debate in visual search: A hybrid approach. In: Shapiro K, editor. The Limits of Attention: Temporal Constraints on Human Information Processing. Oxford: Oxford U. Press; 2001. pp. 178–198. [Google Scholar]

- Pashler H. Dual-task interference in simple tasks: Data and theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:220–244. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelli DG. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: Transforming numbers into movies. Spatial Vision. 1997;10(4):437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R. A theory of memory retrieval. Psych Review. 1978;85(2):59–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Starns JJ. Modeling multichoice decisions, response times, and confidence judgments. Nat Neurosci. 2012 submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Starns JJ. Modeling confidence judgments, response times, and multiple choices in decision making: recognition memory and motion discrimination. Psychol Rev. 2013;120(3):697–719. doi: 10.1037/a0033152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond JE, Shapiro KL, Arnell KM. Temporary suppression of visual processing in an RSVP task: An attentional blink? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1992;18:849–860. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.18.3.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider W, Shiffrin RM. Controlled and automatic human information processing: I. Detection, search, and attention. Psychological Review. 1977;84(1):1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro KL, Raymond JE, Arnell KM. Attention to visual pattern information produces the attentional blink in rapid serial visual presentation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1994;20:357–371. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.20.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standing L. Learning 10,000 pictures. Q J Exp Psychol. 1973;25(2):207–222. doi: 10.1080/14640747308400340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg S. High-speed scanning in human memory. Science. 1966;153:652–654. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3736.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward R, Duncan J, et al. The slow time-course of visual attention. Cognitive Psychology. 1996;30(1):79–109. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1996.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson AB, Pelli DG. QUEST: a Bayesian adaptive psychometric method. Percept Psychophys. 1983;33(2):113–120. doi: 10.3758/bf03202828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickens DD, Moody MJ, Dow R. The nature and timing of the retrieval process and of interference effects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1981;110(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe JM. Moving towards solutions to some enduring controversies in visual search. Cogn Sci. 2003;7(2):70–76. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)00024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe JM. Saved by a log: how do humans perform hybrid visual and memory search? Psychol Sci. 2012;23(7):698–703. doi: 10.1177/0956797612443968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe JM, Cave KR, Franzel SL. Guided search: An alternative to the feature integration model for visual search. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1989;15:419–433. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.15.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohary E, Hochstein S. How serial is serial processing in vision? Perception. 1989;18(2):191–200. doi: 10.1068/p180191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]