Abstract

The occurrence of Plasmodium vivax malaria was reported in Nouakchott, Mauritania in the 1990s. Several studies have suggested the frequent occurrence of P. vivax malaria among Nouakchott residents, including those without recent travel history to the southern part of the country where malaria is known to be endemic. To further consolidate the evidence for P. vivax endemicity and the extent of malaria burden in one district in the city of Nouakchott, febrile illnesses were monitored in 2012–2013 in the Teyarett health center. The number of laboratory-confirmed P. vivax cases has attained more than 2,000 cases in 2013. Malaria transmission occurs locally, and P. vivax is diagnosed throughout the year. Plasmodium vivax malaria is endemic in Nouakchott and largely predominates over Plasmodium falciparum.

Malaria has been known to be endemic, with occasional and sometimes deadly epidemics, in the Sahelian southern Mauritania, bordering Senegal and Mali, two West African countries where malaria has been endemic for centuries.1 In one of the first epidemiological studies on malaria conducted during the colonial period in 1945–1946 along the Senegal River that forms a natural boundary between Senegal and Mauritania, Plasmodium falciparum (133 of 180 positive smears, 74%) largely predominated over Plasmodium vivax (8%) and Plasmodium malariae (18%).2 The primary vector was reported to be Anopheles gambiae sensu lato in that study. However, two further studies conducted in southern Mauritania in the 1960s did not confirm the presence of P. vivax, and of the two human malaria species found, P. falciparum largely predominated over P. malariae.3,4 The rest of the country is mostly desert where it had been thought that rare cases of malaria occurred sporadically in the transition zone between Sahel and Saharan regions or that the zone was free of malaria.1,3–5

When Mauritania gained independence from France, Nouakchott, a former tiny fishing village situated in the Saharan region (18°6′ north, 15°57′ west) where a French military outpost was established to control the trade route between Morocco and Senegal, became the new capital city in 1958. Its climate is characterized by a long dry season and a short rainy season. At that time, only Anopheles pharoensis, considered to be an inefficient vector of malaria parasites, was captured in Nouakchott.6 Until the 1980s, Nouakchott was considered to be free of autochtonous malaria, and few cases of P. falciparum and Plasmodium ovale diagnosed in the city were attributed to migrants and travelers from southern Mauritania.7

Despite contradictory earlier reports,2–4 the presence of P. vivax in the country in the 1990s is supported by the passive surveillance system of imported malaria in the United States that had detected few cases (1 in 1992, 2 in 1995, and 3 in 2000) of P. vivax-infected travelers returning from Mauritania.8–10 Moreover, between 1995 and 1998, five imported cases of P. vivax malaria in France originated from Mauritania.11 It was suggested for the first time in a study conducted in 1996 that, based on the observation of malaria-positive Mauritanian residents in Nouakchott without any recent travel history to endemic areas, P. vivax transmission may occur in Nouakchott.12 In another study conducted in Rosso, situated along the Senegal River, during the dry season in 2004–2006, most P. vivax-infected patients had a recent travel history to Nouakchott, and the authors suggested that these patients had been infected in the capital city.13

Studies conducted in Mauritania until 2006 were based on microscopic examination of blood smears.2–4,12,13 In more recent studies conducted between 2007 and 2010 in P. vivax-infected children without travel history outside Nouakchott, Plasmodium species identification was confirmed by both rapid diagnostic test for malaria and polymerase chain reaction (PCR).14–16 These studies support the hypothesis that P. vivax malaria has emerged in Nouakchott. The aim of this study was to monitor the current trend of laboratory-confirmed malaria cases in one of the health centers in Nouakchott.

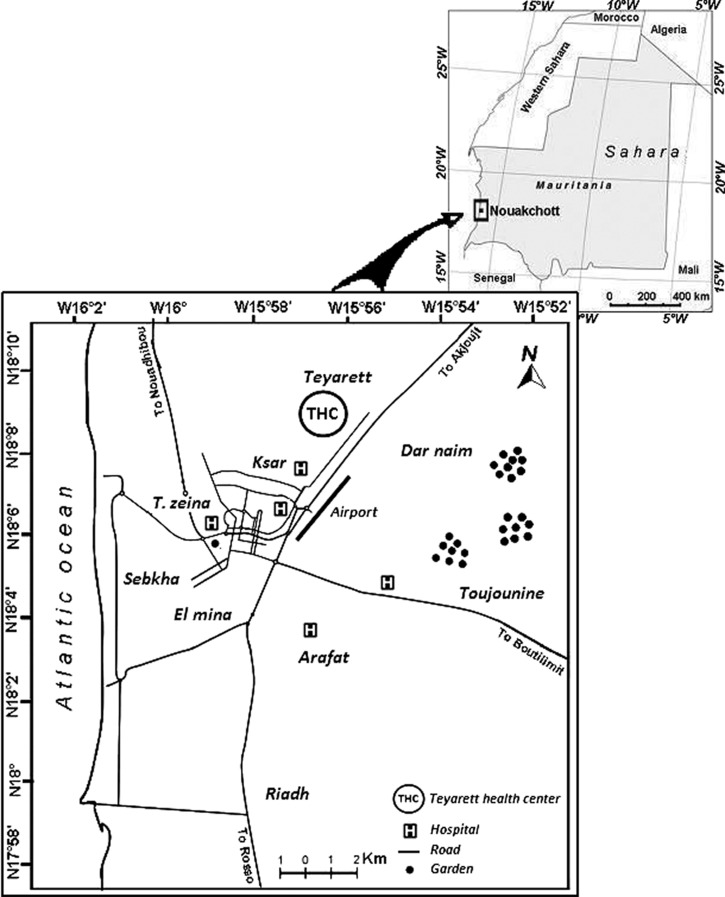

From January 2012 to December 2013, the monthly malaria incidence was followed among febrile patients presenting spontaneously at Teyarett health center, situated about 9 km from the Atlantic coast and 2 km from the international airport (Figure 1). The choice of this health center was based on the results of previous studies that have shown that P. vivax malaria is highly prevalent among febrile patients residing in this district.14–16 As part of the routine diagnostic procedures recommended by the Mauritanian Ministry of Health, all patients with fever or recent history of fever and symptoms suggestive of malaria were screened for malaria using a rapid diagnostic test (SD Bioline P. falciparum histidine-rich protein II and P. vivax plasmodial lactate dehydrogenase antigen rapid diagnostic test; Standard Diagnostics, Inc., Yongin, Republic of Korea) provided by the Ministry of Health. Patients with a positive test were treated with artesunate-amodiaquine, the first-line drug for uncomplicated malaria (for all Plasmodium spp.) since 2006 in Mauritania. Patients with severe and complicated falciparum malaria were referred to a tertiary hospital for parenteral treatment with quinine. This study was reviewed and approved by the Mauritanian Ministry of Health.

Figure 1.

Map of Nouakchott showing Teyarett district and the location of Teyarett health center.

An adequate supply of rapid diagnostic tests to screen all suspected malaria cases was available starting October 2012. Plasmodium vivax malaria was diagnosed throughout the year, possibly including relapses during the dry season, with a peak occurring in October and November, just after the rainy season (August–September) (Figure 2). From January 2012 to December 2013, 4,971 of 9,141 rapid diagnostic tests were positive for P. vivax. Although the present data are incomplete from January to September 2012, the complete data confirmed by the rapid diagnostic test between October 2012 and December 2013 indicate that 54% of clinically suspected malaria cases were caused by P. vivax. The other three human malaria species, P. falciparum, P. malariae, and P. ovale, were not detected during the study period. Moreover, as part of the quality control of laboratory diagnosis of malaria and evaluation of chloroquine efficacy to treat P. vivax infections, about 10% of blood samples with a positive rapid diagnostic test for P. vivax in October and November 2013 were confirmed by both microscopy and PCR. In an earlier study conducted in three different hospitals in 2009–2010,15 102 P. vivax-positive patients were found among febrile children born and residing in Nouakchott. Although this study included febrile adult patients, an exponential increase in laboratory-confirmed P. vivax cases was observed in 2012–2013.

Figure 2.

Number of Plasmodium vivax-infected patients diagnosed by rapid diagnostic tests in Teyarett health center, Nouakchott, Mauritania, in 2012–2013. *Because of an inadequate supply of rapid diagnostic tests for malaria between January and September 2012, data on laboratory-confirmed malaria are incomplete during this period. All suspected cases of malaria were confirmed with the rapid diagnostic test from October 2012 to December 2013.

Over the decades, Nouakchott has undergone a major urban transformation and attracted up to one-fourth of the nation's population (809,360 inhabitants in 2013). Major urbanization projects included an agricultural development and irrigation system within the city confines, potable water supply transported by pipelines from the Senegal River, household and community water supplies, including water fountains, standpipes, and water tanks, and improvement of land routes, transportation, and communication. Economic development also encouraged frequent travels of Nouakchott residents to and from malaria-endemic regions, favoring the circulation of malaria-infected Mauritanians within the country and possibly transport of Anopheles arabiensis to the capital city. Some poorly executed urbanization programs have had a major repercussion on malaria transmission. These include the lack of a water evacuation system, which is the principal cause of annual flooding in Nouakchott, insufficient tap water distribution system, and water leakage from water pipelines and water fountains that serve the city residents. These environmental changes have resulted in the development of An. arabiensis habitats in the city.14 Man-made environmental changes are therefore major factors that have created mosquito habitats in Nouakchott.17 Entomological studies have further shown the presence of P. vivax parasites in the salivary glands of An. arabiensis captured in Nouakchott, indicating that P. vivax transmission occurs locally (Lekweiry KM, unpublished data).

In addition to the environmental factors, human genetic factors favor the endemicity of P. vivax malaria in Nouakchott. Although there is no census based on the demographic weight of different ethnic groups, more than 90% of febrile children spontaneously consulting health centers in Nouakchott were Moors of Arab descent, and the rest of the patients belonged to one of the three ethnic groups of black African origin, namely Poular, Soninke, and Wolof.15 A large majority of Moors in Nouakchott are Duffy positive, whereas individuals of black African descent are mostly Duffy negative.7,18 Although Duffy-negative Mauritanians of black African origin can be infected by P. vivax in rare cases,18 Duffy factor on the surface of erythrocytes is thought to be the major receptor required by P. vivax merozoites to invade the erythrocyte.

The present data, and those of earlier reports,12,14,15 strongly support the emergence and establishment of P. vivax in Nouakchott, where environmental, entomological, and human genetic factors favor autochtonous malaria transmission. Rare cases of P. falciparum diagnosed in Nouakchott, mostly during the rainy season, may be imported from southern Mauritania.14,15 Further studies are being conducted to detect P. falciparum in mosquitoes captured in Nouakchott. Moreover, alternative treatment regimens, including chloroquine and primaquine, are being evaluated. Although the geographic origin of P. vivax in Mauritania is currently unknown, there is strong evidence that malaria transmission occurs locally and is highly prevalent after the rainy season. Although malaria was eliminated from Morocco in 2010 and Algeria has entered into a malaria elimination phase, an opposite trend was observed in Nouakchott, Mauritania, where the prevalence of P. vivax malaria among febrile patients is increasing at an alarming rate. Urgent measures are required to reverse this trend and control malaria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mohamed Lemine Ould Khairy and Saidou Doro Niang (Mauritanian Ministry of Health), Boubacar Abdel Aziz (World Health Organization country office, Nouakchott, Mauritania), and the medical staff of Teyarett health center for support and assistance. We also thank Mohamed Ali Ould Lemraboutl and Rabia Mint Abdellahi for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study was supported by a project grant (No. 12INI215) from the Global Fund through France Expertise Internationale.

Authors' addresses: Mohamed Salem Ould Ahmedou Salem, Khadijetou Mint Lekweiry, Jemila Mint Deida, and Ali Ould Mohamed Salem Boukhary, Unité de Recherche “Génome et Milieux,” Faculté des Sciences et Techniques, Université des Sciences, de Technologie et de Médecine, Nouveau Campus Universitaire, BP 5026, Nouakchott, Mauritania, E-mails: salem0606@yahoo.fr, pekou2006@yahoo.fr, mila1717@live.fr, and alimedsalem@gmail.com. Ahmed Ould Emouh and Mohamed Ould Weddady, Teyarett Health Center, Moughata'a de Teyarett, Nouakchott, Mauritania, E-mails: ahdmouh@gmail.com and drweddady@yahoo.fr. Leonardo K. Basco, Unité Mixte de Recherche 198, Unité de Recherche des Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales Emergentes, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, Faculté de Médecine La Timone, Aix-Marseille Université, 13385 Marseille, France, E-mail: lkbasco@yahoo.fr.

References

- 1.Farinaud ME. La lutte contre le paludisme dans les colonies françaises. Ann Med Pharm Col. 1935;33:919–969. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sautet J, Ranque J, Vuillet F, Vuillet J. Quelques notes parasitologiques sur le paludisme et l'anophélisme en Mauritanie. Med Trop (Marseille) 1948;8:32–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Escudie A, Hamon J. Le paludisme en Afrique occidentale d'expression française. Med Trop (Marseille) 1961;21:661–687. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbié Y, Timbila R. Notes sur le paludisme en République Islamique de Mauritanie. Med Trop (Marseille) 1964;24:427–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monjour L, Richard-Lenoble D, Palminteri R, Ribeiro CD, Alfred C, Gentilini M. A sero-epidemiological survey of malaria in desert and semi-desert regions of Mauritania. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1984;78:71–73. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1984.11811775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamon J, Maffi M, Ouedraogo CS, Djime D. Notes sur les moustiques de la République Islamique de Mauritanie. Bull Soc Entomol Fr. 1964;69:233–253. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lepers JP, Simonneau M, Charmot G. Etude du groupe sanguine Duffy dans la population de Nouakchott (Mauritanie) Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1986;79:417–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anonymous Malaria surveillance–United States, 1992. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anonymous Malaria surveillance–United States, 1995. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anonymous Malaria surveillance–United States, 2000. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gautret P, Legros F, Koulmann P, Rodier MH, Jacquemin JL. Imported Plasmodium vivax malaria in France: geographical origin and report of an atypical case acquired in Central or Western Africa. Acta Trop. 2001;78:177–181. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(00)00181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cortes H, Morillas-Marquez F, Valero A. Malaria in Mauritania: the first cases of malaria endemic to Nouakchott. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:297–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ould Abdallahi M, Ould Bezeid M, Dieye M, Yacine B, Faye O. Etude de la part du paludisme chez les consultants fébriles et des indices plasmodiques chez des écoliers dans la region du Trarza, République islamique de Mauritanie. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2011;104:288–290. doi: 10.1007/s13149-011-0157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mint Lekweiry K, Ould Abdallahi M, Ba H, Arnathau C, Durand P, Trape JF, Ould Mohamed Salem A. Preliminary study of malaria incidence in Nouakchott, Mauritania. Malar J. 2009;8:92. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mint Lekweiry K, Basco LK, Ould Ahmedou Salem MS, Eddine Hafid J, Marin-Jauffre A, Ould Weddih A, Briolant S, Bogreau H, Pradines B, Rogier C, Trape JF, Ould Mohamed Salem Ould Boukhary A. Malaria prevalence and morbidity among children reporting at health facilities in Nouakchott, Mauritania. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011;105:727–733. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mint Lekweiry K, Ould Mohamed Salem Boukhary A, Gaillard T, Wurtz N, Bogreau H, Hafid JE, Trape JF, Bouchiba H, Ould Ahmedou Salem MS, Pradines B, Rogier C, Basco LK, Briolant S. Molecular surveillance of drug-resistant Plasmodium vivax using pvdhfr, pvdhps and pvmdr1 markers in Nouakchott, Mauritania. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;67:367–374. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ould Ahmedou Salem MS, Mint Lekweiry K, Mint Hasni M, Konate L, Briolant S, Faye O, Ould Mohamed Salem Boukhary A. Characterization of anopheline (Diptera: Culicidae) larval habitats in Nouakchott, Mauritania. J Vector Borne Dis. 2013;50:302–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wurtz N, Mint Lekweiry K, Bogreau H, Pradines B, Rogier C, Ould Mohamed Salem Boukhary A, Eddine Hafid J, Ould Ahmedou Salem MS, Trape JF, Basco LK, Briolant S. Vivax malaria in Mauritania includes infection of a Duffy-negative individual. Malar J. 2011;10:336. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]