Abstract

Objective

Although most intensive care unit (ICU) admissions originate in the emergency department (ED), a substantial number of admissions arrive from hospital wards. Patients transferred from the hospital ward often share clinical characteristics with patients admitted from the ED, but family expectations may differ. An understanding of the impact of ICU admission source on family perceptions of end-of-life care may help improve patient and family outcomes by identifying those at risk for poor outcomes.

Design and Setting

Cohort study of patients with chronic illness and acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation who died after ICU admission in 14 Seattle-Tacoma area hospitals between 2003 and 2008 (n=1500).

Measurements

Using regression models adjusted for hospital site and patient-, nurse- and family-level characteristics, we examined associations between ICU admission source (hospital ward versus ED) and 1) family ratings of satisfaction with ICU care, 2) family and nurse ratings of quality of dying; and 3) chart-based indicators of palliative care.

Main Results

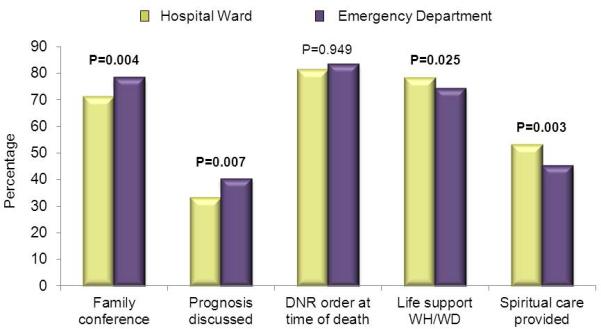

Admission from the hospital ward was associated with lower family ratings of quality of dying (β −0.90, 95% confidence interval (CI) −1.54,−0.26, p=0.006) and satisfaction (total score β −3.97, 95% CI −7.89,−0.05, p=0.047; satisfaction with care domain score β −5.40, 95% CI −9.44,−1.36, p=0.009). Nurses did not report differences in quality of dying. Patients from hospital wards were less likely to have family conferences (odds ratio (OR) 0.68, 95% CI 0.52,0.88, p=0.004) or discussion of prognosis in the first 72 hours after ICU admission (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.56,0.91, p=0.007) but were more likely to receive spiritual care (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.14,1.93, p=0.003) or have life support withdrawn (OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.04,1.82, p=0.025).

Conclusion

Admission from the hospital ward is associated with family perceptions of lower quality of dying and less satisfaction with ICU care. Differences in receipt of palliative care suggest that family of patients from the hospital ward receive less communication. Nurse ratings of quality of dying did not significantly differ by ICU admission source, suggesting dissimilarities between family and nurse perspectives. This study identifies a patient population at risk for poor quality palliative and end-of-life care. Future studies are needed to identify interventions to improve care for patients who deteriorate on the wards following hospital admission.

Keywords: End-of life care, intensive, care, critical care, palliative care, quality

INTRODUCTION

Transfers from hospital wards account for 14-28% of all ICU admissions [1-3]. Patients who experience clinical deterioration on the hospital ward possess a significant burden of comorbidities and exhibit a high severity of illness at the time of ICU admission[4, 5]. These patients experience higher mortality than patients admitted from the emergency department (ED) [4, 6], with longer duration of time spent on the wards associated with greater risk of death [7]. Like patients admitted to the ICU from the ED, patients admitted to the ICU from the hospital ward are often unable to participate in decision-making following ICU admission [8]. Though most ICU patients share a similar reliance on family members to act as surrogate decision-makers [9, 10], disparate pathways to the ICU may promote significant differences in family attitudes and expectations following ICU admission.

Little is known about the influence of ICU admission source on family perceptions of end-of-life care or potential implications for delivery of palliative care. Both family expectations and clinician communication practices may differ by ICU admission source, and these differences have the potential to influence satisfaction with care. Family member expectations for patient recovery may negatively influence ratings of care when a patient's projected course changes significantly. This may be particularly true when conflicting information about prognosis is provided by transferring and accepting physicians [11]. In addition, compared to patients admitted directly from the ED, patients from the hospital ward often come to the ICU accompanied by existing treatment plans. Communication with family members may be limited if clinicians do not perceive this transition as a major departure from preexisting care. We hypothesized that these differences would manifest as lower ratings of satisfaction with care, lower ratings of the quality of dying, and receipt of fewer elements of palliative care for patients admitted to the ICU from the hospital ward, compared to patients admitted from the ED. Importantly, a limited understanding of the experiences and perspectives of family members of patients transferred to the ICU from the hospital ward is a barrier to addressing potential deficiencies in care. We undertook this study in order to enhance our understanding of the quality of care provided to this important patient population with an interest in identifying those at risk for poor quality care and identifying potential targets for future intervention.

Utilizing data from a multi-center trial of a quality improvement intervention to enhance palliative care in the ICU [12] we identified individuals with chronic illness and acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation and examined associations between ICU admission source (hospital ward versus ED) and the following outcomes: 1) family ratings of satisfaction with ICU care as measured by the Family Satisfaction in the ICU survey; 2) family and nurse ratings of quality of dying as measured by the single-item Quality of Dying and Death question; and 3) indicators of palliative care in the ICU. A version of this research has been presented in abstract form [13].

METHODS

Participants and Setting

We used data from a multi-center, randomized trial of an intervention to enhance palliative care in the ICU for patients and their family [12]. Eligible patients were those who died in an ICU after a minimum stay of 6 hours or who died within 30 hours following transfer to another hospital location. Patients were identified by daily examination of admission, discharge, and/or transfer records at 15 Seattle-Tacoma hospitals, with study deaths from 2003 to 2008. The intervention was not associated with improvements in outcomes [12], so all patients were combined into one group for this analysis.

For this analysis, information regarding ICU admission source was available from 14 participating hospitals, including 2 university-affiliated hospitals, 3 community-based teaching hospitals, and 9 community-based, non-teaching hospitals. We excluded patients who spent ≤1 day on the wards or >1 day in the ED (n=241). Additional criteria for inclusion identified patients with chronic illness and similar utilization of life-sustaining measures: 1) acute respiratory failure requiring either non-invasive or invasive mechanical ventilation; and 2) the presence of one or more chronic comorbidities, including dementia, heart failure, malignancy, HIV infection, chronic renal disease, diabetes, cirrhosis, connective tissue disease, chronic immunosuppression, chronic respiratory disease, or cerebrovascular disease (Online supplement e-Figure 1). All study procedures were approved by institutional review boards at each institution.

Data Collection and Variables

Methods for survey collection have been previously described [12]. Briefly, study materials were sent to patients’ homes 4 to 6 weeks after patient death, addressed to the family of the patient. A letter was included with mailed surveys with instructions specifying that the family member who had the most knowledge of the care received by the patient during his/her ICU stay should complete the questionnaire. Nurse questionnaires were delivered within 72 hours of death to the hospital mailbox of the nurse caring for the patient at the time of death/transfer as well as the nurse from the previous shift. Additional follow-up mailings included reminder/thank-you postcards sent 3 weeks after initial distribution and a second set sent to non-respondents after 5 weeks.

Trained chart abstractors reviewed patients’ medical records using a standardized protocol. Training included a minimum of 80 hours of practice abstraction with guided practice charts and independent chart review, followed by reconciliation with the abstraction trainers. We required 95% agreement with the trainer prior to independent review. Five percent of all charts were co-reviewed to ensure > 95% agreement on all data elements.

Outcome Variables

The following outcomes were obtained from family and nurse surveys: 1) family ratings of ICU care as measured by the Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit (FS-ICU); 2) family ratings on the single-item Quality of Dying and Death (QODD-1) question; and 3) nurse ratings on the QODD-1. Palliative care elements were abstracted from the medical record. Power calculations for the FS-ICU and QODD-1 outcomes are included in the online supplement.

The FS-ICU is a reliable and valid questionnaire [14, 15]; scoring based on 24 items provides scores for total satisfaction and two subscale scores, satisfaction with care and satisfaction with decision making [16]. Scoring involves recoding and recalibrating individual items to a 0-100 range with higher scores indicating increased satisfaction. Scores are calculated by averaging the available recalibrated items, provided the respondent answered at least 70% of items in the relevant score.

The QODD-1 provides a succinct measure of the overall quality of dying using a single-item summary question: “Overall, how would you rate the quality of your loved one's dying?” Items are rated on an 11 point scale, ranging from 0 (a “terrible experience) to 10 (an “almost perfect” experience). Compared to the QODD-22, a 22-item family-assessed Quality of Dying and Death questionnaire, the QODD-1 has demonstrated stronger associations with quality of care [17]. Scores on the QODD-1 have been associated with patient and family-centered decision making, communication with patients and families, and symptom management and comfort care [17]. Higher scores correlate with multiple chart-based markers of high-quality end-of-life care, including the presence of standardized comfort care order sets and the occurrence of a family conference [17]. The QODD-1 was also found to differentiate the quality of care provided in ICUs by physicians from various specialties [18]. Although the minimally important difference has not been defined, a difference of 0.7 on a 1-10 scale was found between those who died in the setting of their choice (home or hospital) compared to those who did not die in the setting of their choice [19].

Evaluation of palliative care delivery in the ICU included assessment of five quality indicators of palliative and end-of-life care documented in the medical record. These were considered secondary outcomes and included: 1) family conference within 72 hours of ICU admission; 2) prognosis discussed within 72 hours of ICU admission; 3) involvement of a spiritual care provider, including a pastor, chaplain, or spiritual advisor; 4) presence of do not resuscitate (DNR) orders at the time of death; and 5) withholding or withdrawing of life support. These items were chosen based on a consensus conference to reflect the quality and quantity of palliative care provided to patients in the ICU [20, 21].

Predictor variables

The primary exposure was ICU admission source, defined as either hospital ward or ED.

Potential confounders

We included hospital site as a covariate in all analyses because we found important differences in outcomes by site [22]. We investigated several patient and family characteristics as potential confounders, including age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Additional variables assessed for patients included comorbidities, cause of death (Cancer, Trauma, or Other), hospital admission source, and ICU service. Family characteristics included the relationship with the patient (e.g. spouse, parent, child), years the family member had known the patient, and a variable indicating if the family member lived with the patient. The medical record provided information on patient age, sex, hospital admission source, and comorbidities. Washington State releases confidential death certificate data linked by a patient identifier for research purposes. We used these records for patient race/ethnicity, and cause of death; if data were unavailable or incomplete in the death certificate, we used medical record data. Specialty of discharge attending physician (i.e. medicine, surgery, etc.) was used as a proxy for specialty of the physician providing ICU care. Family member age, sex, race/ethnicity, and relationship to the patient were obtained from family survey data. For nurses, survey responses provided nurse age, sex, race/ethnicity, and years of critical care experience.

Analysis

Analyses for this study utilized regression to assess associations between ICU admission source and our outcomes of interest. Potential confounders were evaluated for each outcome as follows: 1) variables related to either the patient or family for family-assessed outcomes; 2) variables related to either the patient or nurse for nurse-assessed outcomes; or 3) variables related to the patient for chart-assessed outcomes. Outcomes from family surveys were independent observations with one survey per family member but, because some nurses completed surveys for more than one patient, nurse surveys were not independent. Thus, for evaluation of nurse-assessed outcomes we used clustered regression to account for correlations within nurses. We used dummy indicators to adjust for hospital site in all regression models [23, 24].

For each outcome, we built regression models that involved our predictor, the outcome of interest, and hospital site. We then separately evaluated each potential confounder for its effect on the primary predictor's coefficient when compared with the model adjusting for hospital site only. If addition of the variable changed the coefficient of the predictor of interest by more than 10%, the variable was defined as a confounder and used as a covariate in the final model [25]. Scores on the FS-ICU and QODD-1 were evaluated as continuous variables using multivariable robust linear regression and elements of palliative care were evaluated as binary variables using multivariable robust logistic regression. The proportion of patients with completed family or nurse surveys was compared by ICU admission source using the chi-squared test. Assessment of patient characteristics was performed using two-sample t test with unequal variances, Chi-square test, or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Analyses were performed using STATA 13.0 (College Station, TX) with statistical significance for all hypothesis tests set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Sample and Measures

We identified 1500 patients with chronic life-limiting illness and acute respiratory failure; 460 (31%) were admitted to the ICU from the hospital ward and 1040 (69%) were admitted to the ICU from the ED. Mean patient age was 70.4 years (SD 13.9) and 58% of patients (n=877) were male. The majority of patients were white, non-Hispanic (77%), and most were admitted to the hospital from home (63%). Of the evaluated comorbidities, malignancy, chronic respiratory disease, diabetes mellitus, and chronic heart failure were most common, and most patients were cared for by medicine or medicine subspecialty services (89%). Mean family member age was 57.9 years (SD 14.6) and the majority of family respondents were female (69%). Patient characteristics by ICU admission source are described in Table 1. Individuals admitted to the ICU from hospital ward had a longer mean ICU length of stay than patients admitted from the ED, spending 7.4 days (SD 10.8) in the ICU compared to 5.2 days (SD 7.5). For patients admitted to the ICU from hospital ward, average length of stay prior to transfer was 10 days (SD 12.9). Compared to patients admitted from the hospital ward, patients admitted from the ED were more likely to have a DNR order in place (24% versus 3%) by the end of their first hospital day (e-Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by ICU Admission Sourcea

| Wards (n=460) | ED (n=1040) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at death, mean (SD) | 69.3 (12.8) | 70.8 (14.4) | 0.038 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.004 | ||

| Male | 294 (64) | 583 (56) | |

| Female | 166 (36) | 457 (44) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | 0.114 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 364 (79) | 784 (75) | |

| Hispanic or Non-white | 96 (21) | 256 (25) | |

| Cause of death, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Cancer | 111 (24) | 113 (11) | |

| Trauma | 21 (5) | 76 (7) | |

| Other | 328 (71) | 851 (82) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Malignancy | 199 (43) | 270 (26) | < 0.001 |

| Respiratory disease | 203 (44) | 372 (36) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 175 (38) | 411 (40) | 0.589 |

| Heart failure | 115 (25) | 282 (27) | 0.392 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 69 (15) | 207 (20) | 0.024 |

| Immunosuppressive state | 65 (14) | 58 (6) | < 0.001 |

| Liver disease | 52 (11) | 77 (7) | 0.013 |

| Dementia | 48 (10) | 139 (13) | 0.113 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 40 (9) | 115 (11) | 0.166 |

| Connective tissue disease | 12 (3) | 26 (3) | 0.902 |

| HIV/AIDS | 10 (2) | 17 (2) | 0.469 |

| Hospital admission source, n (%) | 0.012 | ||

| Home | 315 (69) | 629 (61) | |

| Acute care facility | 62 (14) | 147 (14) | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 54 (12) | 191 (18) | |

| Group home | 5 (1) | 21 (2) | |

| Office/clinic | 8 (2) | 12 (1) | |

| Rehab | 6 (1) | 18 (2) | |

| Homeless | 3 (1) | 14 (1) | |

| Unknown | 7 (2) | 8 (1) | |

| Discharge service, n (%) | 0.565 | ||

| Medicine (or subspecialty) | 407 (89) | 922 (89) | |

| Surgical | 49 (11) | 114 (11) | |

| Other | 3 (1) | 3 (0) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | |

| ICU LOS (days), mean (SD)b | 7.4 (10.8) | 5.2 (7.5) | < 0.001 |

| Ward LOS (days), mean (SD) | 10.0 (12.9) |

ICU Intensive care unit ED Emergency department HIV/AIDS Human immunodeficiency virus/Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome LOS Length of stay

Tests of association performed with two-sample t test with unequal variances, Chi-square test, or Fisher's exact test as appropriate.

Information on ICU length of stay based on data from 1497 of 1500 patients.

Family members provided 581 surveys, each completed by a unique family member participant. This provided family responses for 38.7% of patients (37.6% for patients admitted from the hospital ward and 39.2% for patients admitted from the ED; p=0.55). Because nurses could evaluate more than one patient's death, nurses could provide more than one survey for analysis. There were 610 surveys from 380 nurses, providing nurse responses for 40.7% of patients (43.3% for patients admitted from the hospital ward and 39.5% for patients admitted from the ED; p=0.17). There were 260 patients who had a survey from both a family member and a nurse. Family characteristics are presented in Table 2 and nurse characteristics in an online supplement (e-Table 2). Unadjusted FS-ICU ratings, QODD-1 ratings, and elements of palliative care are described by ICU admission source in Table 3.

Table 2.

Family Characteristics by ICU Admission Source

| Patient Admission Source | ||

|---|---|---|

| FAMILY CHARACTERISTICSa | Wards (n=173) | ED (n=408) |

| Age at time of survey, mean (SD)b | 58.3 (15.0) | 57.8 (14.5) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 54 (31) | 114 (28) |

| Female | 116 (67) | 283 (69) |

| Unknown | 3 (2) | 11 (3) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 143 (83) | 325 (80) |

| Hispanic or Non-white | 26 (15) | 67 (16) |

| Unknown | 4 (2) | 16 (4) |

| Relationship to Patient, n (%) | ||

| Spouse/Domestic partner | 91 (53) | 161 (40) |

| Child | 56 (32) | 153 (38) |

| Sibling | 13 (8) | 26 (6) |

| Parent | 6 (4) | 13 (3) |

| Other relative | 3 (2) | 35 (9) |

| Friend | 1 (1) | 11 (3) |

| Unknown | 3 (2) | 9 (2) |

| Lived with patient, n (%)c | 111 (64) | 220 (54) |

| Years of relationship with patient, mean (SD)d | 42.1 (16.2) | 43.9 (15.8) |

ICU Intensive care unit ED Emergency department

Surveys completed by 38.7% of family members, 37.6% among family members of patients admitted from the wards and 39.2% for patients admitted from the emergency department.

Ages were reported by 565 of 581 family members.

Living arrangement reported by 567 of 581 family members.

Years of relationship with patient reported by 574 of 581 family members.

Table 3.

Unadjusted Survey Scores and Elements of Palliative Care by ICU Admission Sourcea

| Patient Admission Source | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ward | ED | N | β/OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Survey Scores, mean (SD) | ||||||

| QODD-1 Ratingsb | ||||||

| Family scores | 6.5 (3.3) | 7.3 (2.9) | 555 | −0.82 | −1.41,−0.24 | 0.006 |

| Nurse scores | 7.1 (2.9) | 7.3 (2.6) | 564 | −0.16 | −0.66,0.33 | 0.510 |

| FS-ICU Ratingsc | ||||||

| Total satisfaction | 74.1 (22.6) | 79.1 (18.1) | 566 | −4.94 | −8.77,−1.10 | 0.012 |

| Satisfaction with care | 75.0 (22.2) | 80.7 (18.3) | 563 | −5.64 | −9.46,−1.83 | 0.004 |

| Satisfaction with decision-making | 73.5 (25.1) | 76.7 (20.6) | 572 | −3.21 | −7.49,1.06 | 0.141 |

| Elements of Palliative Care in the ICU, % | ||||||

| Family conference, 1st 72 hrs of ICU admission | 71 | 78 | 1493 | 0.70 | 0.54,0.89 | 0.004 |

| Prognosis discussed, 1st 72 hrs of ICU admission | 33 | 40 | 1492 | 0.75 | 0.59,0.94 | 0.014 |

| DNR order in place at the time of death | 81 | 83 | 1488 | 0.84 | 0.64,1.12 | 0.242 |

| Life support withheld or withdrawn | 78 | 74 | 1490 | 1.20 | 0.92,1.56 | 0.174 |

| Spiritual care provided | 53 | 45 | 1498 | 1.33 | 1.07,1.66 | 0.012 |

ICU Intensive care unit ED Emergency department QODD-1 Quality of Dying and Death single item FS-ICU Family Satisfaction in the ICU survey DNR Do not resuscitate β Beta coefficient OR Odds ratios

Tests of association performed with robust linear regression (providing β) or logistic regression (providing OR) as appropriate.

Scoring based on responses to a single-item summary question, rated on an eleven point scale (0-10) with higher scores reflecting a better experience.

Scoring based on 24 items provides score for total satisfaction and two subscale scores, satisfaction with care and satisfaction with decision-making. Scores range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating higher satisfaction.

Family Member and Nurse Perceptions of ICU Care and Quality of Dying

We identified significant associations between ICU admission source and family ratings of satisfaction with care and quality of dying. Family members of patients admitted to the ICU from the hospital ward provided mean unadjusted ratings of quality of dying of 6.5 (95% CI 5.94,6.96) compared with 7.3 (95% CI 6.99,7.57) for patients admitted from the ED. Family of patients admitted from the hospital ward also provided lower ratings of satisfaction with ICU care (75.0, 95% CI 71.66,78.41) compared to family of patients admitted from the ED (80.7, 95% CI 78.87,82.50). These differences remained significant after adjustment (Table 4). There were no significant associations identified between ICU admission source and either family satisfaction with decision-making or nurse-rated quality of dying (Table 4).

Table 4.

Survey Scores and Indicators of Palliative Care: Associations with ICU Admission Sourcea, Adjusted for Potential Confounders

| N | β | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QODD-1 Ratingsb | ||||

| Family ratingsc | 544 | −0.90 | −1.54,−0.26 | 0.006 |

| Nurse ratings | 564 | −0.12 | −0.62,−0.37 | 0.628 |

| FS-ICU Ratingsb | ||||

| Total satisfactiond | 566 | −3.97 | −7.89,−0.05 | 0.047 |

| Satisfaction with care | 563 | −5.40 | −9.44, −1.36 | 0.009 |

| Satisfaction with decision-making | 572 | −2.77 | −7.16,1.62 | 0.216 |

| N | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elements of Palliative Care in the ICUe | ||||

| Family conference, 1st 72 hrs of ICU admission | 1493 | 0.68 | 0.52,0.88 | 0.004 |

| Prognosis discussed, 1st 72 hrs of ICU admission | 1492 | 0.72 | 0.56,0.91 | 0.007 |

| DNR orders in place at the time of death | 1488 | 1.01 | 0.74,1.38 | 0.949 |

| Life support withheld or withdrawnd | 1490 | 1.38 | 1.04,1.82 | 0.025 |

| Spiritual care provided | 1498 | 1.48 | 1.14,1.93 | 0.003 |

ICU Intensive care unit QODD-1 Quality of Dying and Death single item FS-ICU Family Satisfaction in the ICU survey

Admission source coded as a binary variable, emergency department (0) and hospital ward (1).

Estimates for family- and nurse-assessed outcomes from multivariable robust linear regression models with all models adjusted for hospital site.

Model adjusted for spousal relationship with patient.

Model adjusted for patient age.

Estimates for chart-assessed outcomes from multivariable robust logistic regression models, with all models adjusted for hospital site.

Indicators of Palliative Care in the ICU

For most family members, there was documentation of some form of communication within the first 72 hours of ICU admission, but 23% had neither a family conference nor a documented discussion of prognosis during that time period (21% of family members of patients from the ED and 28% of family members of patients from the hospital ward). Compared to family of patients admitted to the ICU from the ED, family members of patients admitted from the hospital ward were less likely to have a family conference within the first 72 hours of ICU admission (71% [95% CI 0.68,0.75] versus 78% [95% CI 0.75,0.80]) and were less likely to have discussions of prognosis during that time period (33% [95% CI 0.29,0.37] versus 40% [95% CI 0.37,0.43]). The presence of a DNR order at the time of death did not differ significantly by ICU admission source, but patients from hospital ward were more likely to have life support withheld or withdrawn (hospital ward 78% [95% CI 0.74,0.81] versus ED 74% [95% CI 0.72,0.77]) and to receive spiritual care during their ICU stay (hospital ward 53% [95% CI 0.48,0.57] versus ED 45% [95% CI 0.42,0.48]). Figure 1 and Table 4 describe adjusted differences in palliative care for patients admitted to the ICU from the hospital ward, compared to those admitted from the ED.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of palliative and end-of-life care by intensive care unit (ICU) admission source. Family conferences and discussions of prognosis were those occurring within the 1st 72 hours of ICU admission. P values are from multivariable robust logistic regression models. WH/WD Withheld or withdrawn.

DISCUSSION

In this observational analysis of 1500 patients with chronic illness and acute respiratory failure who died following ICU admission, we identified significant associations between admission source and family ratings of quality of dying and satisfaction with ICU care. Family of patients admitted to the ICU from hospital wards were less satisfied with the ICU care they and their loved ones received and provided lower ratings of quality of dying. Our findings suggest that admission source influences family member assessments of quality of end-of-life care in the ICU. One possible explanation is that patients with chronic illness who began their hospitalization on the hospital ward experience a lower quality of communication about end-of-life care prior to ICU admission. Inadequate communication with seriously ill, hospitalized adults about treatment preferences is common [26], and the failure to involve these patients in discussions about goals of care has been characterized as a ‘medical error’ [27]. This error of omission is even more troubling when it involves patients with chronic illness experiencing clinical deterioration following hospitalization. Although these patients can often participate in discussions about end-of-life care at the time of hospital admission, they are frequently unable to do so once critically ill [8]. Thus, the decision to transfer patients to the ICU often occurs without adequate discussion of goals of care [28], placing patients at risk for receiving undesired interventions and shifting the burden of decision-making to family. The provision of care inconsistent with patient preferences can negatively impact the experience of surrogate decision-makers [29], and efforts to address patients’ goals prior to death may improve family satisfaction [30]. The effects of poor communication on the hospital ward may persist throughout a patient's hospitalization and result in perceptions of lower quality of dying in the ICU and lower satisfaction with ICU care.

Another potential explanation for our findings is that family expectations are conditioned by admission source in a way that influences family perceptions of dying in the ICU. Family of patients with chronic illness who begin their hospitalization on the hospital ward may have a certain understanding of the projected course of their loved one's illness. When a period of clinical deterioration occurs, unmet expectations may influence family satisfaction for the remainder of the hospitalization, particularly for patients who die following ICU transfer. Lower family ratings of satisfaction with care and quality of dying for patients admitted from the wards may reflect frustration with an unexpected change in trajectory of illness. In addition, our findings suggest that clinicians may fail to take advantage of communication opportunities to modify family expectations following ICU admission. We found that family of patients admitted from the hospital ward received less communication following ICU transfer, as compared to family members of patients admitted from the ED. Patients from the hospital ward and their families often have established relationships with a variety of healthcare providers and typically arrive in the ICU with preexisting treatment plans. These factors may dissuade providers from actively engaging family members of transferred patients, particularly if transfer to the ICU is perceived simply as a continuation of care. For family members, fewer elements of communication coupled with unmet expectations may contribute to lower family satisfaction. Improved communication between transferring providers from the hospital ward and accepting physicians in the ICU may offer an opportunity to explore family member expectations, identify unaddressed issues pertaining to preferences and goals of care, and improve the quality of care for patients and their family members.

Our findings suggest that patients admitted from the hospital ward to the ICU may be important targets for interventions to improve quality of end-of-life care. Although reasons for admission may differ [4], patients from both the ED and hospital wards are critically ill at the time of ICU admission and experience significant mortality. It is troubling that patients admitted from the wards received fewer elements of communication but were more likely to have life support withdrawn than patients admitted from the ED. Trials of intensive care may be employed in the setting of prognostic uncertainty, but these should occur in conjunction with adequate communication with surrogate decision-makers [31]. In the absence of timely communication, treatment plans cannot be aligned with patient goals and decisions regarding withholding or withdrawal of life-sustaining measures may be delayed. Importantly, duration of time spent on the hospital ward prior to ICU transfer has been suggested as an important trigger for palliative care consultation [32]. An intervention that requires a family conference within the first 72 hours of ICU admission from the hospital ward may provide an opportunity to clarify goals of care and avoid continued provision of life-sustaining measures if this is not consistent with patient goals. This may have implications both for family satisfaction with end-of-life care and length of stay in the ICU [33].

The finding that nurse ratings did not significantly differ by pre-admission location underscores the need to explore family perspectives. Discordance between clinician and family perceptions of quality of dying has been previously documented and this finding highlights the importance of perspective as well as the need to evaluate clinician and family satisfaction separately [34]. It is possible that duration of hospitalization may influence perceptions of quality of dying. For family members of patients spending several days on the hospital ward prior to ICU admission, their impression of quality of dying may take the entire hospitalization into account. ICU nurses, on the other hand, experience only the portion of a patient's stay which involves ICU care. That nurses did not report differences in quality of dying may serve as a reminder that clinicians are often unaware of frustrations felt by family of critically ill patients [35]. Vigilance on the part of providers may allow recognition of dissatisfaction and allow family member concerns to be promptly addressed. This may not only improve the quality of care for patients and family, but might also attenuate the anxiety and post-traumatic symptoms commonly experienced by family members [36].

This study has several important limitations. First, measures of severity of illness at ICU admission were not available. However, all patients included in this study had evidence of chronic life-limiting illness and acute respiratory failure and all patients died during hospital admission, suggesting similar severity of illness. Second, response rates, though similar to other studies enrolling families after death, could introduce response bias. Importantly, the proportion of missing outcome data was similar by ICU admission source, arguing against a differential response bias for our predictor of interest. Third, we did not account for multiple comparisons when assessing quality indicators of palliative care in the ICU and this may have led to spurious associations. However, this was an exploratory analysis that attempted to minimize the chance of false-positive associations by specifying the predictors of interest a priori. Lastly, this study included patients in one geographic area and may not generalize to other regions. Although there is regional variability in end-of-life care in the ICU, this region approximates the intensity of care at the end-of-life in many other regions of the US [37].

In conclusion, we found significant associations between admission source and family ratings of satisfaction with care and quality of dying. Family of patients admitted to the ICU from the hospital ward reported lower satisfaction with care and lower quality of dying for their loved ones, identifying an important target for quality improvement. Furthermore, differences in palliative care following ICU admission suggest that patients transferred from the hospital ward receive less communication. This study identifies a patient population at risk for poor quality palliative and end-of-life care, and admission from the hospital ward may serve as an important indicator alerting clinicians to family members in need of communication strategies that address pre-existing expectations as well as the implications of ICU transfer. Future studies evaluating end-of-life care in the ICU should consider the role of ICU admission source, and additional investigation is needed to develop interventions to improve the quality of palliative care for chronically-ill patients at high risk for clinical deterioration following hospital admission.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Provided by the National Institutes of Health including the National Institute of Nursing Research and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NIH-NINR R01 NR005226; NIH-NHLBI T32 HL007287)

Research conducted at Harborview Medical Center, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Shorr AF, White A, Dremsizov TT, Schmitz RJ, Kelley MA. Critical care delivery in the United States: distribution of services and compliance with Leapfrog recommendations. Critical care medicine. 2006;34:1016–1024. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000206105.05626.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groeger JS, Guntupalli KK, Strosberg M, Halpern N, Raphaely RC, Cerra F, Kaye W. Descriptive analysis of critical care units in the United States: patient characteristics and intensive care unit utilization. Critical care medicine. 1993;21:279–291. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199302000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerlin MP, Small DS, Cooney E, Fuchs BD, Bellini LM, Mikkelsen ME, Schweickert WD, Bakhru RN, Gabler NB, Harhay MO, Hansen-Flaschen J, Halpern SD. A randomized trial of nighttime physician staffing in an intensive care unit. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368:2201–2209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hillman KM, Bristow PJ, Chey T, Daffurn K, Jacques T, Norman SL, Bishop GF, Simmons G. Duration of life-threatening antecedents prior to intensive care admission. Intensive care medicine. 2002;28:1629–1634. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1496-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delgado MK, Liu V, Pines JM, Kipnis P, Gardner MN, Escobar GJ. Risk factors for unplanned transfer to intensive care within 24 hours of admission from the emergency department in an integrated healthcare system. Journal of hospital medicine : an official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2013;8:13–19. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ensminger SA, Morales IJ, Peters SG, Keegan MT, Finkielman JD, Lymp JF, Afessa B. The hospital mortality of patients admitted to the ICU on weekends. Chest. 2004;126:1292–1298. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.4.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldhill DR, McNarry AF, Hadjianastassiou VG, Tekkis PP. The longer patients are in hospital before Intensive Care admission the higher their mortality. Intensive care medicine. 2004;30:1908–1913. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2386-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaros MC, Curtis JR, Silveira MJ, Elmore JG. Opportunity lost: End-of-life discussions in cancer patients who die in the hospital. Journal of hospital medicine : an official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2013;8:334–340. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook D, Rocker G, Marshall J, Sjokvist P, Dodek P, Griffith L, Freitag A, Varon J, Bradley C, Levy M, Finfer S, Hamielec C, McMullin J, Weaver B, Walter S, Guyatt G. Withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in anticipation of death in the intensive care unit. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;349:1123–1132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smedira NG, Evans BH, Grais LS, Cohen NH, Lo B, Cooke M, Schecter WP, Fink C, Epstein-Jaffe E, May C, et al. Withholding and withdrawal of life support from the critically ill. The New England journal of medicine. 1990;322:309–315. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199002013220506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwarzkopf D, Behrend S, Skupin H, Westermann I, Riedemann NC, Pfeifer R, Gunther A, Witte OW, Reinhart K, Hartog CS. Family satisfaction in the intensive care unit: a quantitative and qualitative analysis. Intensive care medicine. 2013;39:1071–1079. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2862-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis JR, Nielsen EL, Treece PD, Downey L, Dotolo D, Shannon SE, Back AL, Rubenfeld GD, Engelberg RA. Effect of a quality-improvement intervention on end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a randomized trial. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011;183:348–355. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-1004OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Long AC, Engelberg RA, Kross EK, Nielsen EL, Back AL, Downey L, Curtis JR. Intensive care unit admission from the acute care floor: is it associated with family or nurse perceptions of lower quality of dying? American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014:A1131. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heyland DK, Tranmer JE. Measuring family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: the development of a questionnaire and preliminary results. Journal of critical care. 2001;16:142–149. doi: 10.1053/jcrc.2001.30163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heyland DK, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, Kutsogiannis DJ, Konopad E, Cook DJ, Peters S, Tranmer JE, O'Callaghan CJ. Family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: results of a multiple center study. Critical care medicine. 2002;30:1413–1418. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Heyland DK, Curtis JR. Refinement, scoring, and validation of the Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit (FS-ICU) survey. Critical care medicine. 2007;35:271–279. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000251122.15053.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glavan BJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Curtis JR. Using the medical record to evaluate the quality of end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Critical care medicine. 2008;36:1138–1146. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318168f301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Cuschieri J, Hallman MR, Longstreth WT, Jr., Tirschwell DL, Curtis JR. Differences in end-of-life care in the ICU across patients cared for by medicine, surgery, neurology, and neurosurgery physicians. Chest. 2014;145:313–321. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Norris K, Asp C, Byock I. A measure of the quality of dying and death. Initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2002;24:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke EB, Curtis JR, Luce JM, Levy M, Danis M, Nelson J, Solomon MZ. Quality indicators for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Critical care medicine. 2003;31:2255–2262. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000084849.96385.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mularski RA, Curtis JR, Billings JA, Burt R, Byock I, Fuhrman C, Mosenthal AC, Medina J, Ray DE, Rubenfeld GD, Schneiderman LJ, Treece PD, Truog RD, Levy MM. Proposed quality measures for palliative care in the critically ill: a consensus from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care Workgroup. Critical care medicine. 2006;34:S404–411. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000242910.00801.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeCato TW, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Nielsen EL, Treece PD, Back AL, Shannon SE, Kross EK, Curtis JR. Hospital variation and temporal trends in palliative and end-of-life care in the ICU. Critical care medicine. 2013;41:1405–1411. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318287f289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moineddin R, Matheson FI, Glazier RH. A simulation study of sample size for multilevel logistic regression models. BMC medical research methodology. 2007;7:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maas CJM, Hox JJ. Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Methodology. 2005;1:86–92. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenland S. Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. American journal of public health. 1989;79:340–349. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.3.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heyland DK, Barwich D, Pichora D, Dodek P, Lamontagne F, You JJ, Tayler C, Porterfield P, Sinuff T, Simon J, Team AS, Canadian Researchers at the End of Life N Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning. JAMA internal medicine. 2013;173:778–787. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allison TA, Sudore RL. Disregard of patients' preferences is a medical error: comment on “Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning”. JAMA internal medicine. 2013;173:787. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rady MY, Johnson DJ. Admission to intensive care unit at the end-of-life: is it an informed decision? Palliative Medicine. 2004;18:705–711. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm959oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vig EK, Starks H, Taylor JS, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Surviving surrogate decision-making: what helps and hampers the experience of making medical decisions for others. Journal of general internal medicine. 2007;22:1274–1279. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2010;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkinson D, Savulescu J. A costly separation between withdrawing and withholding treatment in intensive care. Bioethics. 2014;28:127–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2012.01981.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hua MS, Li G, Blinderman CD, Wunsch H. Estimates of the Need for Palliative Care Consultation across United States Intensive Care Units Using a Trigger-based Model. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014;189:428–436. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201307-1229OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quenot JP, Rigaud JP, Prin S, Barbar S, Pavon A, Hamet M, Jacquiot N, Blettery B, Herve C, Charles PE, Moutel G. Impact of an intensive communication strategy on end-of-life practices in the intensive care unit. Intensive care medicine. 2012;38:145–152. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2405-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levy CR, Ely EW, Payne K, Engelberg RA, Patrick DL, Curtis JR. Quality of dying and death in two medical ICUs: perceptions of family and clinicians. Chest. 2005;127:1775–1783. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuster RA, Hong SY, Arnold RM, White DB. Investigating Conflict in ICUs—Is the Clinicians’ Perspective Enough?*. Critical care medicine. 2014;42:328–335. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a27598. 310.1097/CCM.1090b1013e3182a27598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, Annane D, Bleichner G, Bollaert PE, Darmon M, Fassier T, Galliot R, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Goulenok C, Goldgran-Toledano D, Hayon J, Jourdain M, Kaidomar M, Laplace C, Larche J, Liotier J, Papazian L, Poisson C, Reignier J, Saidi F, Schlemmer B. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2005;171:987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barnato AE, Herndon MB, Anthony DL, Gallagher PM, Skinner JS, Bynum JP, Fisher ES. Are regional variations in end-of-life care intensity explained by patient preferences?: A Study of the US Medicare Population. Medical care. 2007;45:386–393. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000255248.79308.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.