Abstract

The relationship between telomere length (TL) and predisposition to myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) remains unclear. We compared peripheral blood leukocyte (PBL) TL among cases of histologically-confirmed MDS (n=65) who were treatment-naive with no prior cancer history to age-matched controls (n=63). Relative TL was measured in PBL and saliva by quantitative PCR and in CD15+ and CD19+ cells by Flow-FISH. Human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene (hTERT) mutations were assessed by PCR. After adjustment for age and sex, relative TLs were reduced in PBL (p=0.02), CD15+ (p=0.01), CD19+ (p=0.25) and saliva (p=0.13) in MDS cases versus controls, although only PBL and CD15+ results were statistically significant. Among MDS cases, CD15+ and CD19+ cell TLs positively correlated (p=0.03). PBL TL was reduced among those occupationally exposed to paints and pesticides, but was not associated with hTERT genotype. Future studies are needed to further investigate constitutional telomere attrition as a possible predisposing factor for MDS.

Keywords: myelodysplastic syndromes, telomere length, hTERT

Introduction

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are hematopoietic stem cell disorders characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis that progress to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in approximately 30% of cases. Predisposition to MDS has been linked to mutagen exposure and, given its age-dependence, senescence of hematopoietic stem cells and/or conducive changes in the marrow microenvironment.[1] One mechanism through which cells are triggered to enter a state of replicative senescence is telomere shortening, whereby the repeating TTAGGG sequences at the caps of the chromosomes become shorter with each cell division, resulting in chromosomal instability and the eventual halt of cell division[2].

Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with MDS have shortened telomeres compared to healthy controls, based on measurements obtained from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), peripheral blood granulocytes (PBG), bone marrow, and/or CD34+ stem cells[3-7]. Although shortened telomeres could be considered a signature of the disease based on these studies, the role of telomere length in MDS etiology remains unclear. For example, shorter constitutive telomere length, as measured in PBMC, has been associated with several types of solid tumors in epidemiologic studies [8-12], indicating that individuals with shorter telomeres may be at increased risk of developing these cancers. However, in MDS, PBMC's include the malignant tissue, and therefore, it is more difficult to distinguish telomere length measured in peripheral blood as a marker of susceptibility versus disease. Furthermore, there is limited information about the genetic and environmental determinants of telomere length in MDS patients. Loss of function mutations in the human gene for telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) have been previously associated with AML [13, 14] and aplastic anemia (AA) [15], although hTERT mutations and their association with telomere length have not been previously investigated in MDS. Rigolin and colleagues reported that past occupational exposure to toxic substances were associated with shorter telomeres in peripheral blood granulocytes of MDS patients, although specific exposures were not reported[6].

To investigate the association between telomere length and MDS, we conducted a case-control study, including telomere lengths measured in whole blood, CD15+ and CD19+ cells, and saliva. hTERT genotypes were assessed and information on occupational exposures obtained to examine factors potentially associated with telomere length in MDS patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

A case-control study of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) was conducted within the Malignant Hematology Clinic at the Moffitt Cancer Center (“Moffitt”) in Tampa, FL. Cases (n=60) were defined as patients diagnosed with histologically-confirmed MDS and classified by subtype according to the World Health Organization (WHO)[16, 17] and by risk score according to the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) criteria[18]. All patients ages 18 years or older were eligible to participate if they were treatment naive or were undergoing treatment with only growth factors at the time of study enrollment. Patients were excluded if they had received any other types of chemotherapy including experimental therapies, or had a history of another cancer. Five cases of MDS were recruited through a study advertisement posted on The Myelodysplastic Syndromes Foundation, Inc. website for whom copies of original pathology reports were obtained from the treating physicians in order to confirm the MDS diagnosis. All MDS cases were enrolled in the study between September 2006 and May 2008, and efforts were made to recruit patients as close to the time of MDS diagnosis as possible, with a median time between diagnosis and consent of 3.5 months. Of the patients determined to be eligible, more than 95% agreed to participate, and blood was successfully obtained from 93% of those case enrolled (n=65). Controls were visitors who accompanied patients to Moffitt's Malignant Hematology Clinic (n=63) and were frequency-matched to MDS cases based on four age categories (<55, 55-64, 65-74 and 75+ years). Clinic visitors were eligible to be controls if they were not biologically related to the patients they were accompanying to the clinic and did not have a history of cancer. Controls were recruited during the same time period as the MDS cases, and of those determined to be eligible, 100% agreed to participate. All study participants provided informed consent. Study procedures were approved by the institutional review board at the University of South Florida.

Data and Sample Collection

Study participants completed a self-administered risk factor questionnaire, including items on smoking, alcohol consumption, and occupational exposures[19]. Clinical data were abstracted from the medical records and pathology for MDS patients, including WHO subtype, IPSS score and presence of cytogenetic abnormalities. Peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs) were isolated from heparinized whole blood samples by incubation with red blood cell (RBC) lysis solution (Quiagen, Inc, Valencia, CA) for 10 min at room temperature followed by centrifugation and washing with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Because PBL's include both myeloid cells (i.e. the “diseased” tissue in the case of MDS) and lymphocytes (i.e. “normal” tissue), telomere lengths were also measured separately in circulating CD15+ myeloid cells, circulating CD19+ lymphocytes and saliva samples. Telomere length measurement in CD15+ and CD19+ had to be conducted on fresh blood, which was available from 18 MDS cases and 15 controls. Saliva sample collection using commercially available kits[20, 21] was added to the protocol mid-study, and samples were obtained from 17 cases and 14 controls.

Laboratory Methods

Telomere length measurement in peripheral blood leukocytes and saliva

DNA was extracted from samples of heparinized whole blood using the FlexGene DNA Kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), and relative telomere lengths were measured by a modified version of the real-time PCR–based telomere assay described previously[22]. This method has been used in several previous case-control studies of telomere length and cancer[9, 11, 12]. Briefly, the telomere repeat copy number to single gene copy number (T/S) ratio was determined using an Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) 7900 HT PCR system in a 96-well format. Ten ng of genomic DNA was used for either the telomere or hemoglobin PCR reaction. The PCR reactions consisted of 1X Qiagen Quantitect Sybr Green Master Mix with Tel-1b/Tel-2b or hemoglobin (hbg)1/hbg 2 primers. All samples for both the telomere and hemoglobin reactions were done in triplicate in the same plate, and the threshold value for both reactions was set to 0.2. In addition to the samples, each 96-well plate contained a five-point standard curve from 0.08ng to 50 ng using genomic DNA. We ran the standard curve in each plate for assessing inter-variations in PCR efficiency. The mean slope of the standard curve for both the telomere and hbg reactions was -2.84 (range, -2.50 to -3.30), and the linear correlation coefficient (R2) value for both reactions was 0.90 and 0.99, respectively. The T/S ratio (-dCt) for each sample was calculated by subtracting the median hemoglobin threshold cycle (Ct) value from the median telomere Ct value. The relative T/S ratio (-ddCt) was determined by subtracting the T/S ratio of the 10.0 ng standard curve point from the T/S ratio of each unknown sample. The identical method was used to measure telomere length in saliva samples.

Telomere length measurement in circulating CD15+ and CD19+ cells

Telomere lengths were also measured separately in circulating CD15+ myeloid cells (i.e. malignant tissue) and CD19+ lymphocytes (i.e. normal tissue) using a quantitative FISH assay using flow cytometry (flow-FISH) as previously described[23]. Experiments were performed using 6 × 106 fresh PBLs. The samples were processed with Red Blood Cell lysis buffer (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) to preserve the myeloid cell population. Immunofluorescence labeling was performed indirectly, using a CD15 purified antibody (Axxora, Lausen, Switzerland), a GAM Alexa 546 secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), a CD19 biotin antibody (Axxora, ANC-168-030), and a streptavidin APC secondary antibody (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). All antibody stainings were performed at 4°C. Prior to antibody staining, blocking was performed with 200ug/ml goat IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 10 minutes at room temperature. To control for antibody specificity, cells were also labeled with the Alexa 546 and streptavidin APC secondary antibodies in the absence of the CD15 and CD19 antibodies. The cells were first stained with CD15 for 45 minutes, followed by GAM Alexa 546 for 20 minutes. Next, the cells were stained with CD19 biotin for 45 minutes, followed by streptavidin APC for 20 minutes. The antigen-antibody complex was then cross-linked with 2 mM BS3 (Fisher Scientific) chemical cross-linker. PNA-telomere probe binding in a population of cells with long telomeres, Jurkat 1301 T leukemia cell line, (1301 cells) was used as both an internal reference standard in each assay and for quantification. The PBLs were counted following antibody incubation and mixed with 1301 cells (www.ecacc.org.uk) at a 1:1 cell ratio. 5 × 105 PBL's were mixed with 5 × 105 1301 cells. In situ hybridization was performed in hybridization solution (70% formamide, 1% BSA, 20mM Tris pH 7.0) in duplicate and in the presence and absence of a FITC-conjugated Telomere PNA probe (Panagene), FITC-00-CCC-TAA-CCC-TAA-CCC-TAA, complementary to the telomere repeat sequence at a final concentration of 60nM. After addition of the Telomere PNA probe, cells were incubated for 10 minutes at 81°C in a shaking water bath. The synthetic polynucleic acid (PNA) oligonucleotide probe was used to resist degradation at this temperature, as shown previously[24]. The cells were then placed in the dark at room temperature overnight. The next morning, excess telomere probe was removed by washing 2 times with PBS pre-warmed to 40°C. Following the washes, DAPI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added at a final concentration of 75ng/ml. DNA staining with DAPI was used to gate cells in the G0/G1 population. Sample analysis was performed by acquiring the samples on a flow cytometer equipped with a 532-nm laser for excitation of Alexa 546; a 633-nm laser for excitation of APC; a high-power violet 405-nm laser for excitation of DAPI ; and a 488-nm laser for excitation of FITC(LSRII Custom Analyzer, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) in collaboration with the Moffitt Core Facility Flow Cytometry laboratory using FACSDiva v6plus sample acquisition software (BD Biosciences) and Flow Jo 8.7.3 analysis software (Tree Star, Inc, Ashland, OR), Telomere fluorescence of the test sample was expressed as a percentage of the fluorescence (fl) of the 1301 cells according to the following formula: % telomere length = [(*FITC fltest cells w/ probe-*FITC fltest cells w/o probe) × DNA index1301 cells × 100] / [(*FITC fl1301 cells w/probe - FITC fl1301 cells w/o probe) × DNAindex test cells] where *FITC fl is the geometric mean of telomere fluorescence of the G0/G1 population of duplicate samples.

To standardize for cell ploidy, the DNA index was measured for each sample[25]. The DNA index of 1301 cells was 2.07 and the cases and controls ranged from 0.95 to 1.05. 1.5 × 106 cells were washed in PBS and resuspended in 200 microliters PBS. The cell suspension was transferred to tubes containing 2ml 70% ethanol, while vortexing, and stored at -20C. On the day of analysis, the cells were washed twice with 2 ml PBS and resuspended in PBS containing 300 micrograms/ml DNase free RNase and 50 micrograms/ml propidium iodide, and incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes. Trout erythrocyte nuclei (TEN's) (Biosure, Grass Valley, CA) have a DNA content of 80% of human diploid cells and were used as a reference point for DNA ploidy. TEN's were prepared in a separate tube by adding 2 drops of TEN's to PBS containing 50 micrograms/ml propidium iodide.

hTERT genotyping

DNA samples were screened for the presence of the polymorphisms in the hTERT gene by using a PCR/direct sequencing and PRC/RFLP. For direct sequencing, a part of exon 2 was amplified using 100ng hTERT sense and antisense primers to generate a 978 bp fragment. The standard PCR was performed in a 30ul reaction volume containing 40 ng of genomic DNA. The reaction mixtures underwent the following incubations: one cycle of 95 °C for 2 min, 40 cycles of 95C for 30 s, 70C for 30s, and 72°C for 40s. The PCR-amplified hTERT products were directly sequenced at the Molecular Biology Core Facility at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center. We determined the genotypes of 3 SNPs and 2 mutations, located in codons 202, 279, 305, 412, and 441 from sequencing results. Codons 279 (rs6174818) and 412 (rs34094720) polymorphisms were previously shown to be associated with AA [15] and the two mutations, codons 202 and 441, showed high frequency among AA cases. In addition, relatively common synonymous SNP at codon 305 (rs2736098) was also genotyped.

We also determined the identity of each study subject's hTERT codon 1062 polymorphism (rs35719940) which is associated with AA cases, by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis. Briefly, a 152 bp fragment was amplified by PCR using 40 ng of genomic DNA, 100ng of the hTERT F1062 and antisense primers. Four ul of each PCR sample was digested with 5 units of NaeI (New England Biolabs) at 37C overnight and resolved on 8% native polyacrylamide gels to detect differences in RFLP patterns. Three banding patterns were observed: a 152 bp band that corresponded to the wild-type, 152 bp, 92 bp, and 60 bp bands that corresponded to the heterozygous genotype, and 92 bp and 60 bp bands that corresponded to the homozygous polymorphic genotype.

Wang et al. (2003) identified, a novel polymorphic tandem repeats minisatellite, termed MNS16A, in the downstream region of the hTERT gene locus. There were four different MNS16A alleles, classified either as short (S) or long (L). (S) alleles have been associated with increased hTERT mRNA[26]. PCR analysis was performed as previously described by Wang et al (2003) with slight modifications. Briefly, 243, 272, 302, and 333 bp fragments of hTERT 3′UTR region were amplified by PCR using 100ng of the hTERT MNS16A-F sense and antisense primers. PCR products were visualized on an 8% native polyacrylamide gels in order to separate the different alleles: 243 bp, 272 bp (= short alleles), 302 bp and 333 bp (long alleles). Three different MNS16A genotypes were defined on the basis of the functional structure of this tandem repeat minisatellite: LL (homozygotes), SL (heterozygotes) and SS (homozygotes).

Statistical Methods

Among MDS cases, telomere lengths measured in PBL were compared across clinical characteristics (IPSS score, cytogenetics, WHO subtype, and length of time between date of MDS diagnosis and date of study enrollment) using the normal score. Telomere lengths measured in PBL, circulating CD15+ and CD19+, and saliva were compared between MDS cases and controls using multivariable logistic regression models to adjust for potential residual confounding by age (as a continuous variable) and sex. Telomere length measured in PBL was divided into tertiles based on the distribution of values in the controls. Using the longest tertile as a reference group, odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using logistic regression to estimate the magnitude of the association between PBL telomere length and MDS with adjustment for age and sex. Frequencies of hTERT genotypes were compared between cases and controls using Fisher's exact test. PBL telomere length was compared across hTERT genotypes separately in cases and controls using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. All tests were two-sided and associations were considered statistically significant at a significance level of p<0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS (v.9.1., SAS, Cary, NC).

Results

Age was distributed similarly between cases (mean=65.5 years, standard deviation (SD)=12.7 years, range=22-84 years) and controls (mean=64.0 years, SD=12.5 years, p=0.50, range=30-83 years). Of the 65 MDS cases and 63 controls available for analysis, 41 (63.1%) and 28 (44.4%) were male, respectively (p=0.03). PBL telomere lengths are summarized by clinical characteristics for the MDS cases in Table I. Telomere lengths were similar by gender (p=0.58). No statistically significant differences in telomere lengths were observed by IPSS score, cytogenetics or WHO MDS subtype. No differences in telomere length were observed by time since MDS diagnosis, with 80% of MDS cases recruited within one year of diagnosis.

Table I. Clinical characteristics and telomere length measured in peripheral blood leukocytes of 65 myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) cases, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL.

| telomere length | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Characteristic | n | % | mean | SD | p-value* |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 41 | 63.1 | 3.94 | 2.21 | 0.58 |

| Female | 24 | 36.9 | 3.73 | 2.41 | |

| IPSS score | |||||

| Low | 28 | 43.1 | 3.47 | 1.93 | 0.08 |

| Intermediate-1 | 20 | 30.8 | 4.06 | 1.58 | |

| Intermediate-2 | 10 | 15.4 | 4.19 | 3.33 | |

| High | 2 | 3.1 | 1.47 | 0.95 | |

| Unknown | 5 | 7.7 | 5.57 | 3.46 | |

| Cytogenetics | |||||

| Normal | 44 | 67.7 | 4.01 | 2.17 | 0.11 |

| Abnormal | 19 | 29.2 | 3.37 | 2.47 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 3.1 | 5.19 | 2.77 | |

| WHO MDS subtype | |||||

| refractory anemia (RA) | 10 | 15.4 | 2.78 | 2.12 | 0.25 |

| refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia (RCMD) | 21 | 32.3 | 3.64 | 1.81 | |

| RA with ringed sideroblasts (RARS) | 9 | 13.8 | 3.97 | 1.17 | |

| RCMD with ringed sideroblasts (RCMD-RS) | 3 | 4.6 | 3.69 | 0.43 | |

| RA with excess blasts (RAEB)-1 | 10 | 15.4 | 3.84 | 2.13 | |

| RAEB-2 | 9 | 13.8 | 4.49 | 3.47 | |

| unclassifed-MDS (U-MDS) | 1 | 1.5 | 10.71 | † | |

| unknown | 2 | 3.1 | 5.19 | 2.77 | |

| Time from diagnosis to study enrollment | |||||

| ≤3 months | 32 | 49.2 | 3.62 | 2.22 | 0.66 |

| 4-6 months | 8 | 12.3 | 3.45 | 2.00 | |

| 7-12 months | 12 | 18.5 | 4.62 | 2.74 | |

| 13-24 months | 4 | 6.2 | 4.52 | 3.73 | |

| 25-36 months | 6 | 9.2 | 3.33 | 1.15 | |

| 37-50 months | 3 | 4.6 | 4.70 | 0.90 | |

p-values obtained using normal score;

no standard deviation was calculated since there was only one observation in this cell

IPSS=International Prognostic Scoring System; WHO=World Health Organization

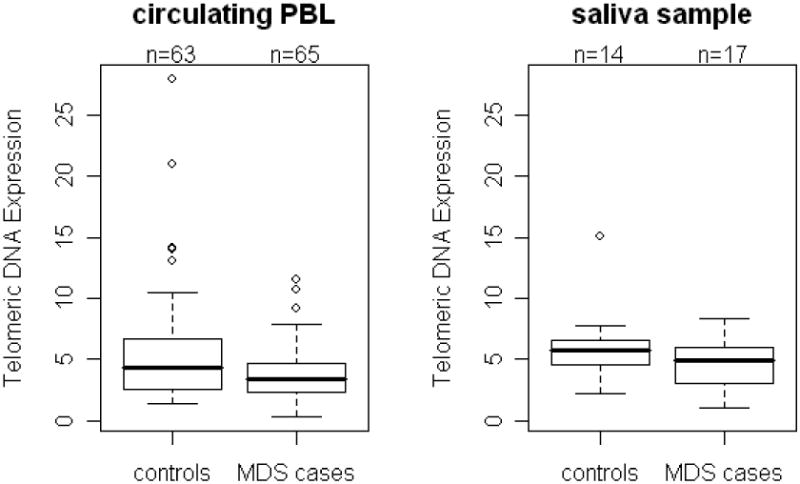

Telomere lengths measured in circulating PBL and saliva are presented for MDS cases and controls in Figure 1. The mean PBL telomere length was statistically significantly shorter among MDS cases (3.86, SD=2.27) compared to controls (mean=5.64, SD=4.62) after adjustment for age and sex (p=0.02) (Figure 1A). When telomere length was divided into tertiles, a two-fold increased risk of MDS was associated with the shortest compared to the longest tertile (OR = 2.29, 95% CI=0.90-5.88). Telomere lengths measured in saliva also tended to be shorter among MDS cases compared to controls for the subset for whom data were available, although this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.13) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Telomere length measured in peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) and saliva samples among MDS cases and controls.

Using quantitative PCR, telomere lengths were measured in (A) PBL from 65 MDS cases and 63 controls and (B) in saliva from 17 MDS cases and 14 controls. Telomere lengths measured in both PBL and saliva were shorter in MDS cases compared to controls. After adjustment for age and sex, the case-control difference was statistically significant for telomere lengths measured in PBL (p= 0.02) but not saliva (p= 0.13).

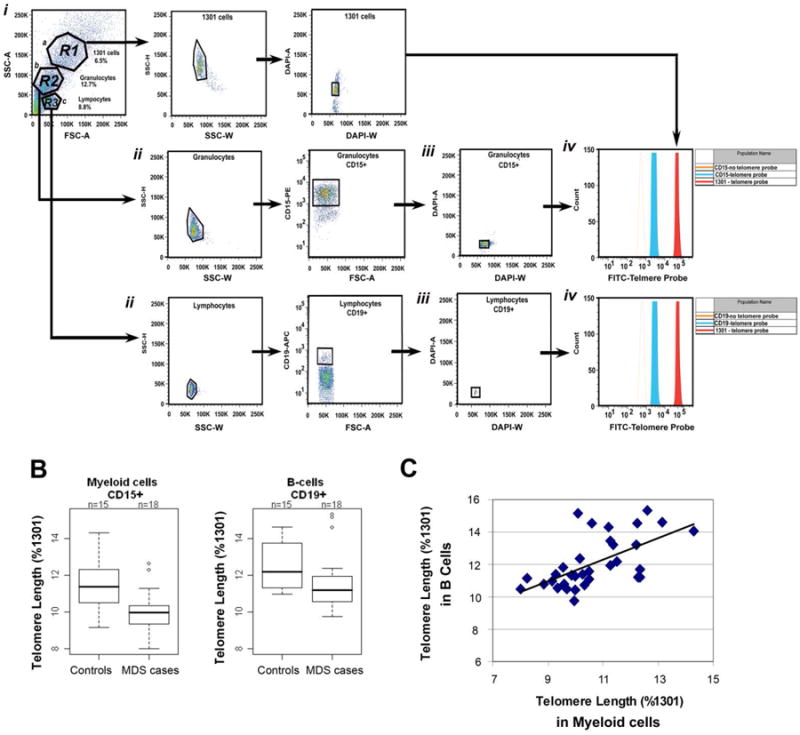

Validation of the flow-FISH telomere assay was performed on human cells from healthy donors prior to analysis of patient samples, Figure 2A. The 1301 human T cell leukemia cell line served as an internal control for all tests due to the presence of long telomeres (Figure 2Aa). These results confirmed that telomere length in patients was sufficiently long to be detected in this assay. Using a flow cytometry gating strategy shown in Figure 2A, gates were placed on CD15+ and CD19+ cells in a subset of 18 MDS cases and 15 controls. Telomere lengths were shorter among MDS in both CD15+ cells and CD19+ cells (Figure 2B), although only the difference in CD15+ telomere length was statistically significant (p=0.01) (Figure 2B). Telomere lengths measured using flow-FISH in circulating CD15+ and CD19+ were statistically significantly, positively correlated in both MDS cases (r=0.50, p=0.03) and controls (r=0.58, p=0.02) (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Telomere length measured in CD15+ and CD19+ in MDS cases and controls by flow-FISH.

Telomere length by flow FISH. (A) Flow cytometry plots showing PBLs from one exemplary patient mixed with 1301 cells. (i) Forward and side scatter plots of the cells for gating: Region 1 (R1) contains 1301 cells, R2 myeloid cells, and R3 lymphocytes. (ii)Gating of R2, was used to identify the CD15 positive myeloid population. Gating of R3 (lymphocyte gate) was used to identify CD19 positive B cells. A sample containing only Alexa 546 and APC secondary antibodies was used as a negative control for CD15 and CD19 staining (not shown). (iii) G0/G1 cells of the CD15 positive, CD19 positive, and 1301 cells were identified by DAPI staining. (iv) G0/G1 gated cells were analyzed for telomere length in the presence (solid red histograms) and absence (open blue histograms) of the FITC labeled telomere PNA probe. The assay was performed in duplicate to demonstrate low inter assay variability. Telomere length fluorescence intensity of cells from MDS patients was compared to that of Jurkat 1301 leukemia T cell line. (B) The telomere length relative to 1301 was calculated in B cells and myeloid cells from 15 MDS patients and 18 healthy controls. Telomere lengths were shorter in MDS cases compared to controls, whether telomere length was measured in CD15+ (p=0.01) or CD19+ cells (p=0.25). (C) Telomere length in B cells (y-axis) was positively correlated with the telomere length in myeloid cells (x-axis) for MDS cases and controls combined (r=0.64, p<0.0001).

The frequencies of SNPs and mutations in hTERT and their associations with PBL telomere length are presented in Table II. No mutations were observed in codons 202, 412 or 441 of Exon 2. No case-control differences were observed in the frequency of mutations or SNPs in codon 279 of Exon 2, codon 305, codon 1062 of Exon 15 or the untranslated region (3′UTR). PBL telomere lengths did not differ by hTERT genotype in cases or controls.

Table II. Human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) genotype, peripheral blood (PBL) telomere length and MDS.

| MDS cases | Controls | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| PBL telomere length | PBL telomere length | ||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| hTERT genotype | n | % | mean (SD) | n | % | mean (SD) | p-value* |

| Codon 279 | |||||||

| GG | 59 | 90.8 | 3.93 (2.32) | 54 | 87.1 | 5.56 (4.78) | 0.58 |

| GA or AA | 6 | 9.2 | 3.22 (1.70) | 8 | 12.9 | 5.09 (2.24) | |

| p-value† | 0.54 | 0.65 | |||||

| Codon 305 | |||||||

| GG | 38 | 58.5 | 3.80 (2.07) | 39 | 62.9 | 5.03 (2.98) | 0.72 |

| GA or AA | 27 | 41.5 | 3.95 (2.56) | 23 | 37.1 | 6.30 (6.35) | |

| p-value | 0.76 | 0.98 | |||||

| Codon 1062 | |||||||

| GG | 61 | 93.8 | 3.87 (2.34) | 61 | 96.8 | 5.69 (4.68) | 0.68 |

| GA or AA | 4 | 6.2 | 3.75 (0.73) | 2 | 3.2 | 4.05 (0.10) | |

| p-value | 0.62 | 0.73 | |||||

| 3′UTR | |||||||

| long/long | 23 | 35.4 | 4.03 (1.70) | 27 | 42.9 | 4.55 (2.39) | 0.59 |

| long/short or short/short | 40 | 61.5 | 3.67 (2.56) | 36 | 57.1 | 6.46 (5.65) | |

| 0.14 | 0.26 | ||||||

p-value based on Fisher's exact test comparing the hTERT genotype distribution between MDS cases and controls

p-value based on Wilcoxon rank sum test comparing telomere lengths by hTERT genotype SD= standard deviation; PBL=peripheral blood leukocyte; hTERT=human telomerase reverse transcriptase

PBL telomere length is compared across categories of smoking status, alcohol consumption, and occupational exposures among MDS cases in Table III. PBL telomere lengths tended to be shorter in ever versus never smokers among the MDS cases, although this difference was not statistically significant, and no pattern in telomere length was observed with pack-years of smoking. Similarly, PBL telomere length did not differ across categories of alcohol consumption. MDS cases who reported occupational exposures to pesticides and paints had statistically significantly shorter PBL telomere lengths than unexposed cases, particularly for exposure to polyurethane paints (p=0.04) and fungicides (p=0.04).

Table III. Smoking, alcohol consumption and occupational exposures in relation to telomere length measured in peripheral blood leukocytes of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) cases.

| relative telomere length | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Characteristic | n | % | mean (SD) | p-value* |

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||

| Never† | 22 | 33.9 | 4.35 (2.45) | |

| Ever | 43 | 66.2 | 3.61 (2.16) | 0.15 |

| Pack-years smoked: | ||||

| <10 | 12 | 18.5 | 3.63 (1.69) | |

| 10-19 | 9 | 13.8 | 2.94 (2.05) | |

| 20+ | 22 | 33.8 | 3.88 (2.44) | 0.41 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| No drinks in past year‡ | 13 | 21.3 | 4.15 (2.98) | |

| Drinking days per month: | ||||

| < 5 | 21 | 34.4 | 3.26 (1.83) | |

| 5-19 | 14 | 23.0 | 3.62 (1.82) | |

| 20+ | 13 | 21.3 | 4.61 (2.62) | 0.48 |

| Occupational exposure to paints | ||||

| None§ | 44 | 68.8 | 4.09 (2.21) | |

| Any | 20 | 31.3 | 3.41 (2.41) | 0.11 |

| Type of paint: | ||||

| Epoxy | 15 | 23.4 | 3.36 (2.69) | 0.09 |

| Polyurethane | 17 | 26.6 | 3.15 (2.46) | 0.04 |

| Latex | 19 | 29.7 | 3.57 (2.36) | 0.20 |

| Occupational exposure to pesticides | ||||

| None§ | 47 | 78.3 | 4.23 (2.44) | |

| Any | 13 | 21.7 | 2.97 (1.48) | 0.09 |

| Type of pesticide: | ||||

| Rodenticides/rat poison | 5 | 8.3 | 2.27 (0.87) | 0.05 |

| Fungicides/mold killers | 6 | 10.0 | 2.22 (0.71) | 0.04 |

| Herbicides/weed killers | 8 | 13.3 | 2.52 (0.95) | 0.05 |

| Insecticides/bug killers | 11 | 18.3 | 2.86 (1.57) | 0.08 |

p-values obtained using normal score;

never smokers served as the reference group for all other categories of cigarette smoking;

those who had no alcoholic drinks in the past year served as the reference group for all other categories of alcohol consumption;

those who reported no occupational exposure served as the reference group for all other categories of exposure

Discussion

In the present study, telomere lengths measured in PBLs and CD15+ were significantly shorter in MDS cases compared to controls, consistent with two previous studies that used Southern blot hybridization to measure telomere length in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), peripheral blood granulocytes (PBG), and/or bone marrow (BM) samples [3, 5] and a third study of telomere length measured in granulocytes and CD34+ cells using flow cytometry[6]. MDS cases in the current study tended also to have shorter telomeres than controls in CD19+ B-lymphocytes (i.e. “normal” blood cells), and although this difference was not statistically significant, there was a statistically significant correlation between telomere lengths in CD19+ and CD15+. Collectively, these findings from case-control studies are consistent with a prospective study demonstrating that shorter PBL telomere lengths were associated with increased risk of treatment-related MDS (t-MDS)/AML among patients undergoing autologous bone marrow transplantation for treatment of lymphoma [27]. In contrast, a recent investigation reported no difference in telomere lengths measured in bone marrow stroma of 38 MDS patients compared to 13 age-matched healthy volunteers[28]. Inconsistent findings across studies could be due to differences in tissue types investigated, since the correlation between telomere lengths measured in different tissues within individuals is largely unknown. The current study is the first to document the correlation between telomere lengths across PBL, CD15+, CD19+ and saliva within MDS patients.

Two polymorphisms in hTERT were observed at similar allele frequencies among MDS cases in the current study compared to AA patients in a previous study[15]. Specifically, the SNP in codon 279 of Exon 2 had an allele frequency in MDS cases of 5.4% compared to 3.0% of AA cases, and the SNP in codon 1062 of Exon 15 had an allele frequency in MDS cases of 3.1% compared to 2.5% of AA cases. However, neither of these SNPs in hTERT was significantly associated with AA or MDS, and in the present study, PBL telomere length did not differ by hTERT genotype in MDS cases or controls. None of the MDS cases in the current study had hTERT variants in codons 412 or 441 of Exon 2, similar to a case-control study of AML in which 1 out of 222 MDS cases had a mutation in each of these two codons [13]. There may be other unmeasured genes in the pathway of telomere maintenance that are important for MDS such as human telomerase RNA (hTERC) or one of the mutant genes in dyskeratosis congenital (DKC1) that encodes for dyskerin, part of the telomerase complex[29-31]. However, two previous studies observed very low frequencies of hTERC mutations in MDS patients.[32, 33] Novel mutations in hTERC and hTERT were recently described in familial MDS[34], although they have not been investigated in sporadic MDS. Of note, none of the MDS cases included in the present study reported a family history of MDS.

Our findings of shorter telomeres associated with past occupational exposures to specific types of paints, and pesticides are consistent with one previous study that reported shorter mean telomere length among individuals with more than 2,400 hours of exposure to any of several occupational exposures assessed[6]. Environmental exposures have been shown to be more strongly associated with MDS characterized by abnormal cytogenetics[35-38], a phenomenon observed in the current study population (data not shown), thus, it is possible that these exposures may contribute to MDS etiology through induction of chromosomal abnormalities, telomere attrition, or both.

There are some limitations of the current study. Sample size was limited, particularly for the sub-analysis by flow-FISH, given that the assays had to be conducted on fresh samples within hours of collection. For example, given the available sample size of 18 cases and 15 controls for the flow-FISH analysis, we had 80% power to detect a case-control difference in telomere length of 1.4, slightly greater than the observed difference of 0.9. However, the current study is the largest to compare telomere lengths measured in different tissues within individuals. The controls, comprised of visitors accompanying patients to the clinic, were not a representative sample of the general population. However, the potential for selection bias is minimal, given that controls were not biologically related to MDS cases and were matched on age. MDS cases could not have had a previous history of cancer or undergone treatment for MDS with the exception of growth factors to be included in this study, limiting the generalizability of findings to higher risk MDS patients. Although exclusion of patients who received chemotherapy ensured that any observed case-control differences in telomere length were not due to chemotherapeutic agents, the potential effects of growth factors on PBL telomere length are unknown. Finally, cases may have had difficulty recalling their past occupational exposures, although they were not aware of their telomere lengths at the time of questionnaire completion, and therefore, the observed associations between exposures and telomere length are not subject to recall bias.

In summary, shortened telomere length was associated with MDS in this case-control study, with statistically significantly shorter telomeres observed in PBL and CD15+. Mutations in hTERT were rare and not associated with telomere length in the current study population. Self-reported occupational exposures to paints and pesticides were associated with shorter telomere lengths among the MDS cases. Taken together, our results suggest that exposures to mutagenic chemicals may induce telomere shortening, thus contributing to the pathogenesis of MDS. Larger studies are needed to further investigate the association between telomere length in normal tissues and MDS, as well as to pinpoint specific exposures associated with MDS potentially through a pathway of telomere attrition, and to investigate novel mutations in hTERT and other genes in the telomere pathway that were not assessed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The project was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute Grant P20 CA103676, R01CA129952 and a Young Investigator Award to DER from The Myelodysplastic Syndromes Foundation, Inc. We thank Kathy Heptinstall and Audrey Hassan from The Myelodysplastic Syndromes Foundation, Inc. for their assistance with study advertisement.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

- 1.Baird DM, Kipling D. The extent and significance of telomere loss with age. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004 Jun;1019:265–8. doi: 10.1196/annals.1297.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Londono-Vallejo JA. Telomere length heterogeneity and chromosome instability. Cancer Lett. 2004 Aug 30;212(2):135–44. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boultwood J, Fidler C, Kusec R, et al. Telomere length in myelodysplastic syndromes. Am J Hematol. 1997 Dec;56(4):266–71. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(199712)56:4<266::aid-ajh12>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brummendorf TH, Holyoake TL, Rufer N, et al. Prognostic implications of differences in telomere length between normal and malignant cells from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia measured by flow cytometry. Blood. 2000 Mar 15;95(6):1883–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohyashiki JH, Iwama H, Yahata N, et al. Telomere stability is frequently impaired in high-risk groups of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Clin Cancer Res. 1999 May;5(5):1155–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rigolin GM, Porta MD, Bugli AM, et al. Flow cytometric detection of accelerated telomere shortening in myelodysplastic syndromes: correlations with aetiological and clinical-biological findings. Eur J Haematol. 2004 Nov;73(5):351–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2004.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sashida G, Ohyashiki JH, Nakajima A, et al. Telomere dynamics in myelodysplastic syndrome determined by telomere measurement of marrow metaphases. Clin Cancer Res. 2003 Apr;9(4):1489–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu X, Amos CI, Zhu Y, et al. Telomere dysfunction: a potential cancer predisposition factor. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003 Aug 20;95(16):1211–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen J, Terry MB, Gurvich I, Liao Y, Senie RT, Santella RM. Short telomere length and breast cancer risk: a study in sister sets. Cancer Res. 2007 Jun 1;67(11):5538–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirabello L, Garcia-Closas M, Cawthon R, et al. Leukocyte telomere length in a population-based case-control study of ovarian cancer: a pilot study. Cancer Causes Control. 2010 Jan;21(1):77–82. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9436-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGrath M, Wong JY, Michaud D, Hunter DJ, De VI. Telomere length, cigarette smoking, and bladder cancer risk in men and women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007 Apr;16(4):815–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jang JS, Choi YY, Lee WK, et al. Telomere length and the risk of lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008 Jul;99(7):1385–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00831.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calado RT, Regal JA, Hills M, et al. Constitutional hypomorphic telomerase mutations in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Jan 27;106(4):1187–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807057106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calado RT, Young NS. Telomere diseases. N Engl J Med. 2009 Dec 10;361(24):2353–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0903373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamaguchi H, Calado RT, Ly H, et al. Mutations in TERT, the gene for telomerase reverse transcriptase, in aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2005 Apr 7;352(14):1413–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting-Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Dec;17(12):3835–49. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.12.3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vardiman JW, Harris NL, Brunning RD. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2002 Oct 1;100(7):2292–302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanz GF, Sanz MA, Greenberg PL. Prognostic factors and scoring systems in myelodysplastic syndromes. Haematologica. 1998 Apr;83(4):358–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarone RE, Alavanja MC, Zahm SH, et al. The Agricultural Health Study: factors affecting completion and return of self-administered questionnaires in a large prospective cohort study of pesticide applicators. Am J Ind Med. 1997 Feb;31(2):233–42. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199702)31:2<233::aid-ajim13>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers NL, Cole SA, Lan HC, Crossa A, Demerath EW. New saliva DNA collection method compared to buccal cell collection techniques for epidemiological studies. Am J Hum Biol. 2007 May;19(3):319–26. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rylander-Rudqvist T, Hakansson N, Tybring G, Wolk A. Quality and quantity of saliva DNA obtained from the self-administrated oragene method--a pilot study on the cohort of Swedish men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006 Sep;15(9):1742–5. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cawthon RM, Smith KR, O'Brien E, Sivatchenko A, Kerber RA. Association between telomere length in blood and mortality in people aged 60 years or older. Lancet. 2003 Feb 1;361(9355):393–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmid I, Dagarag MD, Hausner MA, et al. Simultaneous flow cytometric analysis of two cell surface markers, telomere length, and DNA content. Cytometry. 2002 Nov 1;49(3):96–105. doi: 10.1002/cyto.10163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapoor V, Hakim FT, Rehman N, Gress RE, Telford WG. Quantum dots thermal stability improves simultaneous phenotype-specific telomere length measurement by FISH-flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 2009 May 15;344(1):6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vindelov LL, Christensen IJ, Nissen NI. Standardization of high-resolution flow cytometric DNA analysis by the simultaneous use of chicken and trout red blood cells as internal reference standards. Cytometry. 1983 Mar;3(5):328–31. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990030504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L, Soria JC, Chang YS, Lee HY, Wei Q, Mao L. Association of a functional tandem repeats in the downstream of human telomerase gene and lung cancer. Oncogene. 2003 Oct 16;22(46):7123–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chakraborty S, Sun CL, Francisco L, et al. Accelerated telomere shortening precedes development of therapy-related myelodysplasia or acute myelogenous leukemia after autologous transplantation for lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Feb 10;27(5):791–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcondes AM, Bair S, Rabinovitch PS, Gooley T, Deeg HJ, Risques R. No telomere shortening in marrow stroma from patients with MDS. Ann Hematol. 2009 Jul;88(7):623–8. doi: 10.1007/s00277-008-0649-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calado RT, Young NS. Telomere maintenance and human bone marrow failure. Blood. 2008 May 1;111(9):4446–55. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-019729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calado RT. Telomeres and marrow failure. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009:338–43. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamaguchi H. Mutations of telomerase complex genes linked to bone marrow failures. J Nippon Med Sch. 2007 Jun;74(3):202–9. doi: 10.1272/jnms.74.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohyashiki K, Shay JW, Ohyashiki JH. Lack of mutations of the human telomerase RNA gene (hTERC) in myelodysplastic syndrome. Haematologica. 2005 May;90(5):691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamaguchi H, Baerlocher GM, Lansdorp PM, et al. Mutations of the human telomerase RNA gene (TERC) in aplastic anemia and myelodysplastic syndrome 2. Blood. 2003 Aug 1;102(3):916–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirwan M, Vulliamy T, Marrone A, et al. Defining the pathogenic role of telomerase mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Hum Mutat. 2009 Nov;30(11):1567–73. doi: 10.1002/humu.21115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albin M, Bjork J, Welinder H, et al. Cytogenetic and morphologic subgroups of myelodysplastic syndromes in relation to occupational and hobby exposures. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2003 Oct;29(5):378–87. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ciccone G, Mirabelli D, Levis A, et al. Myeloid leukemias and myelodysplastic syndromes: chemical exposure, histologic subtype and cytogenetics in a case-control study. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1993 Jul 15;68(2):135–9. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(93)90010-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rigolin GM, Cuneo A, Roberti MG, et al. Exposure to myelotoxic agents and myelodysplasia: case-control study and correlation with clinicobiological findings. Br J Haematol. 1998 Oct;103(1):189–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.West RR, Stafford DA, White AD, Bowen DT, Padua RA. Cytogenetic abnormalities in the myelodysplastic syndromes and occupational or environmental exposure. Blood. 2000 Mar 15;95(6):2093–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]