This review attempts to address three fundamental questions clinicians face in choosing first-line and maintenance treatment for advanced non-small cell lung cancer, particularly nonsquamous histology: Is pemetrexed or a taxane agent better for combination with platinum therapy? Should bevacizumab be used, and is it beneficial when added to pemetrexed chemotherapy? When is maintenance therapy indicated, and which agent is best? Differences exist between toxicity profiles of available agents and should guide individual treatment decisions.

Keywords: Lung cancer, Chemotherapy, Metastatic, Disease management

Abstract

Until recently, the first-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) required minimal clinical decision making. Patients who were eligible for chemotherapy received a platinum-based doublet, and 5-year survival rates were poor. With the advent of molecularly targeted agents and better tolerated chemotherapies—namely, bevacizumab, erlotinib, and pemetrexed—new therapeutic opportunities have emerged. Some of the strategies that have proven to be successful for the treatment of patients with NSCLC are targeting of the vascular endothelial growth factor, use of maintenance chemotherapy for patients without progression of disease after initial therapy, and tailoring of cytotoxic agents specific to the histology of an individual patient’s cancer. Each approach has been independently shown to improve overall survival, but integrating the data from a number of complicated trials into the “best” approach for patients remains challenging. This review attempts to address three fundamental questions clinicians face in choosing first-line and maintenance treatment for advanced NSCLC, particularly nonsquamous histology: Is pemetrexed or a taxane agent better for combination with platinum therapy? Should bevacizumab be used, and is it beneficial when added to pemetrexed chemotherapy? When is maintenance therapy indicated, and which agent is best?

Abstract

摘要

直至最近,晚期非小细胞肺癌 (NSCLC) 的一线治疗要求最少临床决策制定。符合化疗条件的患者接受铂类双药,但 5 年生存期率不理想。随着分子靶向药物和耐受性更佳的化疗药物(即贝伐珠单抗、厄洛替尼和培美曲塞)的到来,新治疗机会已经浮现。已经证明成功治疗 NSCLC 患者的一些策略是靶向血管内皮生长因子、初始疗法后对无病情进展的患者使用维持疗法以及定制对个体患者的癌组织结构特异的细胞毒药物。每种方案已经独立地显示改善总生存期,但是将源自许多复杂试验的数据整合成患者的“最佳”方案仍具有挑战性。本综述尝试解决临床医生在选择晚期 NSCLC(尤其是组织学非鳞癌)的一线治疗和维持治疗时面临的三个基础问题:培美曲塞或一种紫杉烷药物比联合铂类药物治疗更好吗? 应当使用贝伐珠单抗并且其增加至培美曲塞化疗时有益吗? 何时提示维持治疗并且哪种药物最好? The Oncologist 2015; 20:299–306

Implications for Practice:

There are many options for first-line and maintenance treatments for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Several available treatment options, such as adding bevacizumab, using pemetrexed for nonsquamous histology, and adding maintenance chemotherapy have been shown to improve overall survival. Key differences exist between toxicity profiles of available agents, and these differences should be used to guide treatment decisions for individual patients. No data support combination maintenance therapy as superior to single agent, but whether an optimal single agent exists is not clear. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 5508 trial (NCT01107626) may help determine whether an incremental benefit with bevacizumab is possible when added to maintenance pemetrexed therapy.

Introduction

Until recently, the first-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) required minimal clinical decision making. Patients who were eligible for chemotherapy received a platinum-based doublet, and 5-year survival rates were poor. Efforts to improve outcomes focused on adjustments to first-line management, such as the optimal duration of therapy of four versus six cycles [1], whether cisplatin was better than carboplatin [2], or the optimal platinum partner [3]. These strategies did not yield any significant improvements in overall survival (OS) rates and were associated with large numbers of treatment-related toxicities, such as neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, neuropathy, and treatment-related mortality in 4%–6% of patients [3].

With the advent of molecularly targeted agents and better tolerated cytotoxic chemotherapies—namely, bevacizumab, erlotinib, and pemetrexed—new therapeutic opportunities have emerged. Clinical trials are now designed to use biomarkers to select patients who are more likely to respond to experimental agents. Well-tolerated chemotherapies are sequenced after platinum-based treatments to extend disease-free and overall survival benefit [4, 5]. Three different therapeutic strategies have been independently shown to improve OS for patients with NSCLC: targeting of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), tailoring of cytotoxic agents specific to the histology of an individual patient’s cancer, and using maintenance chemotherapy for patients without progression of disease after initial therapy. Discoveries of oncogenic driver mutations, such as EGFR-activating mutations and ALK rearrangements, have also dramatically changed the treatment of patients with these mutations [6, 7].

This review will focus on the optimal treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC who have no identifiable driver mutations such as EGFR or ALK, with a particular focus on nonsquamous histology because of the particular complexity of treatment options in this patient population. We will address three fundamental questions clinicians face in choosing a first-line treatment for advanced NSCLC: Is pemetrexed or a taxane better for combination with platinum therapy? Should bevacizumab be used, and when is it beneficial if added to chemotherapy? When is maintenance therapy indicated, and which agent is best?

Materials and Methods

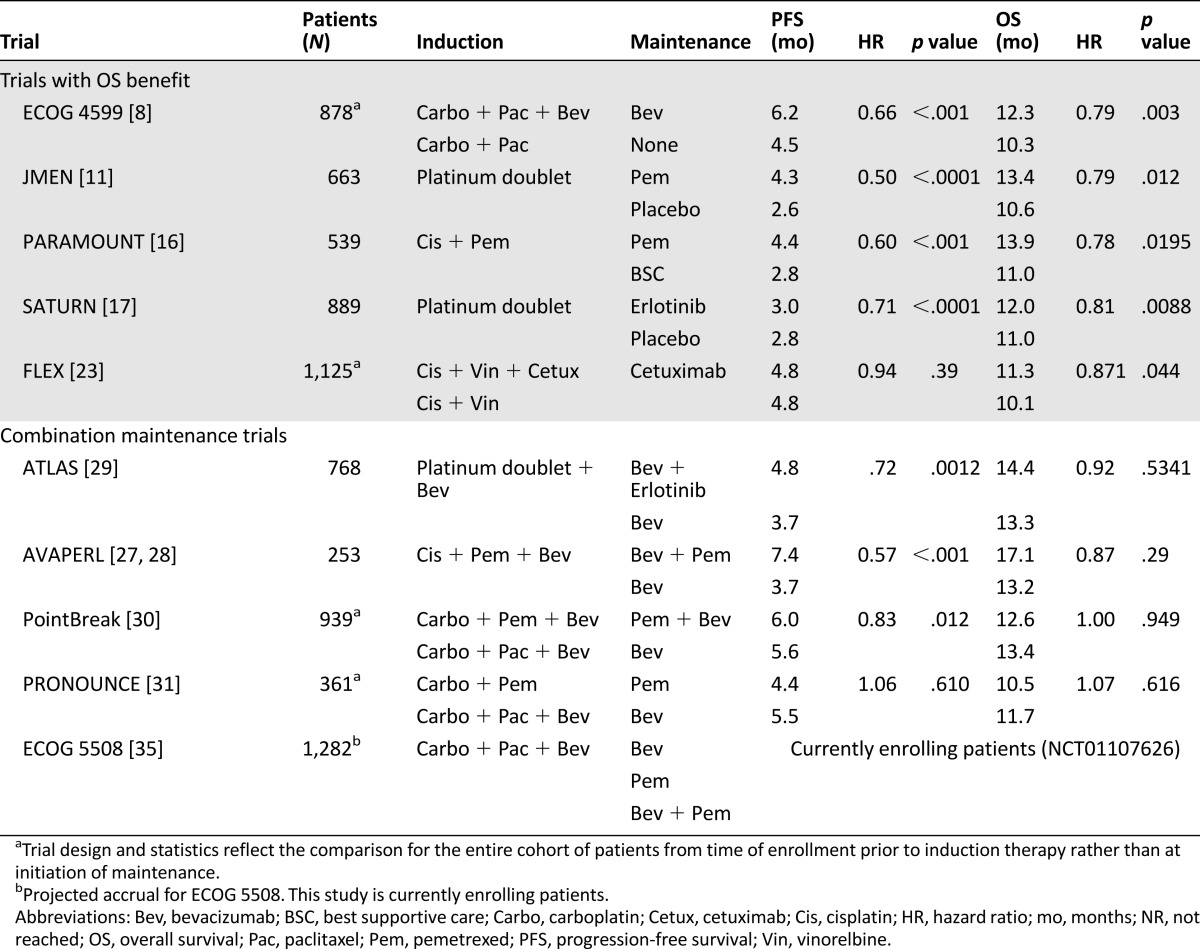

A search of the PubMed database for trials that met the following criteria was conducted: prospective phase III randomized trials for the first-line treatment of metastatic NSCLC that resulted in an improvement in OS and were published in the past 10 years and prospective phase III randomized maintenance trials that combined more than one maintenance therapy for patients with metastatic NSCLC, regardless of outcome. Eligible trials were included in the discussion for this review (Table 1), but an emphasis was placed on trials that demonstrated an improvement in OS or progression-free survival (PFS). Several other phase II or III trials were briefly included to provide context, as necessary. Levels of evidence were not used in trial selection criteria because all of the papers have a high level of evidence (all were prospective, randomized, and phase III).

Table 1.

Key non-small cell lung cancer trials

Background

Trials With an OS Benefit

The first trial to show a significant improvement in OS for patients with NSCLC was the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 4599 trial that added bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting VEGF, to carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy for patients with nonsquamous histology [8]. In this trial of 878 patients, patients were randomized to bevacizumab plus chemotherapy or chemotherapy alone for six cycles. Those receiving the three-drug combination (carboplatin, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab [PacCBev]) lived 2 months longer than their counterparts who did not receive bevacizumab (12.3 vs. 10.3 months; hazard ratio [HR]: 0.79; p = .003). In this trial and all subsequent trials reported to date using this drug, bevacizumab was continued beyond the first four to six cycles until the time of progression or unacceptable toxicity. The addition of bevacizumab also resulted in significant improvements in PFS and response rate (RR). These benefits came at some cost of additional toxicity, particularly increased rates of grade 3 and 4 neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, hyponatremia, hypertension, proteinuria, and bleeding. Although rare, fatal events of febrile neutropenia and hemoptysis were also more common in those patients receiving bevacizumab. In a retrospective analysis of patients separated by age (≥70 vs. <70), so-called elderly patients had no survival benefit from treatment with bevacizumab and had higher levels (87% vs. 61%) of serious adverse events and death [9]. A similar pooled analysis of patients treated with bevacizumab in the ECOG 4599 and PointBreak trials showed benefit with the addition of bevacizumab in patients up to age 74 years but not in those aged 75 and older [10].

Pemetrexed, a folate antimetabolite inhibiting thymidylate synthase, is a second chemotherapy agent to show improved OS for patients with NSCLC. The phase III JMEN maintenance trial—a 663-patient trial that randomized patients to pemetrexed maintenance versus placebo for patients without progression after treatment with a nonpemetrexed platinum doublet—showed an OS benefit with maintenance pemetrexed (13.4 vs. 10.6 months) [11]. In the subgroup analysis by histology, patients with nonsquamous histology treated with pemetrexed showed an even greater OS advantage (15.5 vs. 10.3 months; HR: 0.70; p = .002). Subsequently, the benefit of pemetrexed for patients with nonsquamous histology was demonstrated in first-line therapies.

The phase III noninferiority trial by Scagliotti et al. randomized patients to cisplatin and gemcitabine versus cisplatin and pemetrexed with a preplanned subgroup analysis by histology [12]. The results from this trial met the primary endpoint of noninferiority for the two regimens, but subgroup analysis again demonstrated superior OS for patients with nonsquamous histology receiving pemetrexed compared with gemcitabine (11.8 vs. 10.4 months; HR: 0.81; p = .005). In patients with squamous histology, those receiving cisplatin and gemcitabine had significantly improved OS compared with cisplatin and pemetrexed (10.8 vs. 9.4 months; HR: 1.23; p = .05). The pemetrexed regimen was associated with less grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and febrile neutropenia but more nausea. The JMEN trial [11] and the study by Scagliotti et al. [12] both demonstrated that patients with nonsquamous NSCLC preferentially benefit from pemetrexed chemotherapy, whether used in the maintenance phase or in the first-line setting. These trials, however, did not make any direct comparisons of pemetrexed to other chemotherapy agents, such as paclitaxel or docetaxel. It is also worth noting that neither of these trials used bevacizumab.

Other trials have shown improved OS in the first-line treatment of selected patient populations, such as elderly patients or those with worse performance status. Phase III trials of platinum doublets, such as carboplatin and paclitaxel [13] or carboplatin and pemetrexed [14], have been shown to improve OS in elderly patients aged 70 and older and patients with a performance status of 2, respectively, compared with single-agent chemotherapy. These trials have reinforced the importance of standard treatment approaches for these patient populations but will not be discussed in further detail in this review.

Because both bevacizumab and pemetrexed were effective and well tolerated, they have also been studied as maintenance therapies in hopes of extending survival beyond that possible with platinum-doublet chemotherapy for patients with nonsquamous NSCLC. Switch maintenance, also known as early second-line therapy, in which a non-cross-resistant therapy is introduced after the completion of a platinum-doublet, or continuation maintenance, in which the platinum partner is continued alone after platinum, have both been shown to be effective strategies. The first trial to evaluate the switch maintenance strategy, by Fidias et al., showed improved PFS for maintenance docetaxel after carboplatin and gemcitabine therapy [15]. Maintenance chemotherapy has since been shown to improve OS in several clinical trials. The first was the JMEN trial that identified an OS improvement from pemetrexed maintenance in an unselected patient population [11]. This trial used a switch maintenance strategy with pemetrexed after completion of four to six cycles with a nonpemetrexed platinum doublet. Although both the trial by Fidias et al. and the JMEN trial are touted as proof-of-concept trials that show the benefit for maintenance therapy, they also have been criticized for low rates of patients in the control arms who subsequently received docetaxel or pemetrexed, respectively, after progression.

Continuation maintenance has also been shown to be an effective treatment option capable of improving OS in the PARAMOUNT study [16]. In this trial, 539 patients with nonsquamous NSCLC were treated with cisplatin and pemetrexed followed by continuation of pemetrexed for patients without progression after four cycles of therapy. This continuation maintenance strategy, similar to the JMEN trial, led to a median OS improvement of nearly 3 months (13.9 vs. 11.0 months; HR: 0.78; p = .0195). These trials both showed that maintenance pemetrexed can be given safely and is well tolerated, with only 4% of patients on the maintenance pemetrexed arm in the PARAMOUNT trial developing grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, anemia, or fatigue. In this study, no difference was noted in postdiscontinuation therapies.

One other maintenance trial has shown a small improvement in OS: the SATURN trial, a large trial of 889 patients that randomized patients to switch maintenance with the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib or placebo after four cycles of investigator’s choice of platinum-doublet chemotherapy [17]. The final results identified a small but statistically significant 1-month improvement in median OS (12.0 vs. 11.0 months; HR: 0.81; p = .0088). One of the major limitations of this study that makes it difficult to apply to today’s NSCLC patient populations is that 5% of patients in the erlotinib arm had EGFR-activating mutations, and 6% of patients in the placebo arm also had EGFR mutations, whereas 40% of patients enrolled had missing EGFR mutation status, which may have skewed these results in favor of the erlotinib arm. Today, the majority of these patients (or all, if being treated in a clinical trial) would have EGFR mutation testing prior to starting first-line chemotherapy. Those with activating mutations would be treated with EGFR inhibitors prior to platinum-based chemotherapy based on multiple trials that have shown superiority of anti-EGFR therapy over chemotherapy [6, 18–22]. Because of changes in the diagnosis and treatment practices for EGFR mutations, it is somewhat difficult to apply data from SATURN. Nevertheless, like pemetrexed maintenance, erlotinib maintenance was very well tolerated. Rash was the most common drug-related toxicity, occurring as a grade 3 or 4 event in 9% of patients. All other grade 3 or 4 toxicities occurred at frequencies of ≤2%.

Two EGFR-targeting monoclonal antibodies have led to improved OS in patients with advanced NSCLC. The first phase III trial to demonstrate improved OS was the FLEX trial, which added cetuximab to cisplatin and vinorelbine chemotherapy for patients with EGFR-expressing tumors, defined as EGFR expression by immunohistochemical evidence in at least one tumor cell [23]. The benefits of a 1.2-month improvement in OS were small but statistically significant (11.3 vs. 10.1 months; HR: 0.871; p = .044), although there was no difference in PFS between arms (4.8 months in both arms; HR: 0.943; 95% confidence interval: 0.825–1.077; p = .39). Unlike erlotinib maintenance, cetuximab was associated with a much higher toxicity profile than chemotherapy alone, with increased risk of febrile neutropenia (22% vs. 15%; p = .0086), rash (10% vs. <1%; p = .0001), diarrhea (4% vs. 2%; p = .047), and infusion-related reactions (3% vs. 1%; p = .017). A second phase III trial of cetuximab, the BMS099 trial, randomized patients with metastatic NSCLC to taxane and carboplatin chemotherapy with or without cetuximab [24]. This study was underpowered for OS and showed no improvements in PFS with the addition of cetuximab to chemotherapy (median PFS of 4.4 months with cetuximab vs. 4.2 months without; p = .236). Whether because of a less marked clinical benefit, a more significant toxicity profile, or both, cetuximab maintenance has not been as popular in clinical practice.

The second EGFR antibody, necitumumab, was evaluated in the SQUIRE trial [25]. This phase III, randomized study of 1,093 patients added necitumumab to gemcitabine and cisplatin for the first-line treatment of patients with advanced squamous NSCLC compared with a control arm of gemcitabine and cisplatin alone. Patients randomized to the necitumumab arm had improved overall survival of 1.6 months (11.5 vs. 9.9 months; HR 0.84; p = .012). The addition of necitumumab was associated with higher grade 3 and 4 toxicities including rash and hypomagnesemia.

These seven trials—ECOG 4599, the study by Scagliotti et al., JMEN, PARAMOUNT, SATURN, FLEX, and SQUIRE—represent the only treatment strategies studied to date that are capable of improving the median OS for the first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC. For nonsquamous histology, we can conclude that adding bevacizumab to platinum-paclitaxel chemotherapy improves OS; pemetrexed maintenance, either continuation or switch, improves OS; and pemetrexed is superior to gemcitabine. For squamous histology, strategies targeting EGFR, in particular, necitumumab, have been shown to improve OS.

For nonsquamous histology, we can conclude that adding bevacizumab to platinum-paclitaxel chemotherapy improves OS; pemetrexed maintenance, either continuation or switch, improves OS; and pemetrexed is superior to gemcitabine.

Combination Maintenance: Too Much of a Good Thing?

Investigators have attempted to further extend the OS benefits of pemetrexed and bevacizumab demonstrated in ECOG 4599, JMEN, and PARAMOUNT maintenance strategies by combining these agents or combining bevacizumab with erlotinib in what we will call combination maintenance. A single-arm phase II study by Patel et al. combining pemetrexed and bevacizumab maintenance showed promising improvements in both PFS and OS with acceptable toxicity [26] and set the stage for the four phase III combination maintenance trials that followed: AVAPERL, ATLAS, PointBreak, and PRONOUNCE.

AVAPERL was a European study that enrolled 376 patients—smaller than other combination maintenance trials discussed—who were treated with carboplatin, pemetrexed, and bevacizumab (PemCBev) for four cycles [27]. Patients were then randomized to maintenance bevacizumab alone or pemetrexed and bevacizumab. Patients receiving combination maintenance benefited from prolonged PFS (7.4 vs. 3.7 months; HR: 0.48; p = .001), the study’s primary endpoint, but it was not powered to show a statistically significant improvement in OS (HR: 0.75; p = .219) [28].

The ATLAS trial randomized 743 patients to bevacizumab or bevacizumab plus erlotinib maintenance after completion of 4 cycles of chemotherapy and bevacizumab [29]. Investigators were allowed to choose from six platinum-containing induction regimens. The primary endpoint, PFS, was met and showed a 1-month improvement when adding erlotinib to bevacizumab (4.8 vs. 3.7 months; HR: 0.71; p < .001); however, the 1-month improvement in OS was not statistically significant (14.4 vs. 13.3 months; HR: 0.92; p = .5341), and the addition of erlotinib was associated with significantly higher rates of grade 3 and 4 rash and diarrhea adverse events.

PointBreak was a phase III study that built on the concept of the phase II study by Patel et al. by comparing PemCBev with the regimen used in the ECOG 4599 study, PacCBev, with a primary endpoint of OS [30]. Although this study evaluated two maintenance strategies, its design varied from other maintenance studies in which patients were randomized at the time of initiation of maintenance after successful completion of induction. Instead, patients were randomized up front to two different induction-maintenance strategies: PacCBev followed by bevacizumab maintenance or PemCBev followed by pemetrexed and bevacizumab maintenance. This study showed a small increase in PFS from 5.6 to 6.0 months (PacCBev vs. PemCBev; HR: 0.83; p = .012) and equivalent median OS (13.4 vs. 12.6 mo; p = .949 [HR: 1.00; p = .949]), demonstrating equivalent efficacy for these two regimens.

The PRONOUNCE trial was a randomized phase III trial that compared PacCBev followed by bevacizumab maintenance with carboplatin and pemetrexed followed by pemetrexed maintenance. One might think of this trial design as ECOG 4599 versus PARAMOUNT with carboplatin instead of cisplatin; however, similar to PointBreak, patients were randomized from the outset of the trial. Ideally, this trial would have helped address the unanswered question of whether bevacizumab is superior to pemetrexed as a maintenance therapy. Unfortunately, PRONOUNCE was designed to identify a less toxic regimen and used an endpoint of grade 4 PFS (G4PFS), defined as PFS without development of a grade 4 toxicity [31]. Using this endpoint resulted in a study of 361 patients that was underpowered to evaluate PFS or OS. The study did not meet its primary endpoint of G4PFS, and no differences in PFS or OS were found for the two regimens.

Although these four combination maintenance trials were unable to show a significant OS benefit from combining therapies in the maintenance phase of treatment, AVAPERL, ATLAS, and PointBreak were able to demonstrate that the addition of a second maintenance agent can extend PFS. Although AVAPERL and PRONOUNCE were designed to enable comparison of pemetrexed versus bevacizumab as maintenance agents, neither trial was powered for overall survival comparisons. Perhaps the most definitive conclusion we can draw from these trials is a better understanding of the toxicity differences of these regimens. For many patients, this is the most important consideration, absent significant differences in survival. In PointBreak, patients in the pemetrexed arm were more likely to experience grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia (23% vs. 6%), anemia (15% vs. 3%), and fatigue (11% vs. 5%), and patients in the paclitaxel arm were more likely to have neutropenia (41% vs. 26%), febrile neutropenia (4% vs. 1%), neuropathy (4% vs. 0%), and alopecia (grade 1 or 2; 37% vs. 7%). Similar results were reported in the PRONOUNCE study. Patients in AVAPERL reported grade ≥3 neutropenia (5.6%), hypertension (4.8%), and anemia (3.2%) in the bevacizumab-pemetrexed arm and hypertension and dyspnea (2.5% each) in the bevacizumab-alone arm. Finally, the addition of erlotinib to bevacizumab in ATLAS resulted in enhanced toxicities over those expected from either agent given alone (rash: 6.8% vs. 0.5%, respectively; diarrhea: 9.8% vs. 1.9%, respectively).

Discussion

Although the data presented demonstrate significant progress in treatment options for NSCLC patients, many clinical questions remain unanswered for oncologists attempting to choose between platinum plus pemetrexed with or without bevacizumab and platinum, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab for patients with nonsquamous NSCLC. How do we apply this heterogeneous group of randomized clinical trials to our patients? OS and PFS are not the only factors to consider in choosing a treatment strategy. Even in the presence of an OS advantage, a strategy that is poorly tolerated is unlikely to be adopted in a general lung cancer population. Other clinical trial endpoints, such as RR or toxicity, may be more important when choosing an initial treatment strategy for patients with extensive burden of disease, poor performance status, or comorbidities that may limit the delivery of cytotoxic chemotherapy. We propose the following questions as a practical rubric for interpreting this data: Which platinum partner is better for induction therapy? When is bevacizumab beneficial? Which maintenance strategy is best?

Platinum Partner: Paclitaxel or Pemetrexed?

The results from PointBreak seem to contradict prior data that suggested pemetrexed may be a superior agent for the treatment of patients with adenocarcinoma histology [12]. Although the phase III trial by Scagliotti et al. demonstrated that platinum plus pemetrexed was superior to platinum plus gemcitabine for patients with nonsquamous histology, patients in this trial were not treated with bevacizumab. In considering the data from these two trials, perhaps bevacizumab is an equalizing factor that improves outcomes when paired with paclitaxel but that has no incremental improvement when given with pemetrexed. No phase III randomized clinical trials have evaluated the benefit of adding bevacizumab to platinum and pemetrexed, and no phase III trials have compared pemetrexed and taxanes without bevacizumab. Without clear answers regarding the survival benefits of paclitaxel compared with pemetrexed, other outcome measures, such as RR, may be considered.

Response rates are sometimes used in early phase trials as a surrogate for survival. Are they useful for this paclitaxel-pemetrexed comparison? Partial response rates were similar, ranging from 16% to 21% in the ECOG 1594 study comparing four platinum doublets including cisplatin plus paclitaxel and carboplatin plus paclitaxel [3]. The trial by Scagliotti et al. comparing platinum plus gemcitabine and platinum plus pemetrexed did not report response rates [12]. Although it is difficult to compare across trials, response rates were slightly higher in the PARAMOUNT trial (complete and partial response rates were 30% with cisplatin plus pemetrexed) compared with data on four other platinum doublets in the ECOG 1594 trial. An additional 3% of patients in PARAMOUNT achieved a partial response during the maintenance phase. The PRONOUNCE trial, which compared carboplatin plus pemetrexed with carboplatin, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab, showed similar objective response rates (ORRs) of 23.5% and 27.4%, respectively [31]. Finally, in PointBreak, the ORR and the disease control rate were similar in both arms, using a pemetrexed- or paclitaxel-based regimen [32]. Although reported response rates were higher in PARAMOUNT, suggesting that pemetrexed might be most favorable, all other studies indicated equivalent response rates between pemetrexed and paclitaxel, even when bevacizumab was added to both the induction and maintenance regimens (PointBreak).

The RR of another agent, the albumin-bound formulation of paclitaxel, nab-paclitaxel, was compared with carboplatin and paclitaxel in a randomized phase III trial [33]. In this study, 1,052 patients were randomized, and those in the nab-paclitaxel arm had a significantly higher ORR than those in the soluble paclitaxel arm (33% vs. 25%; p = .005). In subset analysis by histology, those with squamous histology had a significant improvement in ORR, whereas those with adenocarcinoma did not. There were no significant differences in PFS or OS. The nab-paclitaxel arm had lower rates of grade 3 or 4 neuropathy and neutropenia but higher rates of thrombocytopenia and anemia. Based on the available data on response rates, it would be reasonable to conclude that nab-paclitaxel is more likely to achieve a response than paclitaxel in squamous histology, whereas pemetrexed may be better than taxanes for patients with nonsquamous histology who are ineligible for bevacizumab; however, no direct evidence exists to compare pemetrexed and taxanes.

What Is the Role of Bevacizumab?

We know that the addition of bevacizumab to platinum plus paclitaxel improves OS for patients with nonsquamous histology, as demonstrated in ECOG 4599. The addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy has been shown to increase the response rates in the ECOG 4599 trial (35% in the bevacizumab arm vs. 15% in the carboplatin and paclitaxel arm). We also know that this is equivalent to PemCBev followed by maintenance with pemetrexed plus bevacizumab (PointBreak), and the addition of pemetrexed to bevacizumab maintenance may improve PFS for patients receiving pemetrexed induction chemotherapy (AVAPERL). Not all nonsquamous NSCLC patients are eligible for bevacizumab treatment because of contraindications. Bevacizumab should not be used in patients with squamous histology because of the increased risk of hemoptysis, as first noted in a phase II trial prior to ECOG 4599 [34]. It should also be avoided in patients with high risk of bleeding or thrombosis, including those with recent stroke, myocardial infarction, or surgery.

One key question remains for patients eligible to receive bevacizumab: Does the addition of bevacizumab to pemetrexed-based regimens improve OS? In other words, would the results of PRONOUNCE have been any different if it had been powered to evaluate OS? This question is likely to remain unanswered in the near future. It is also unclear whether bevacizumab is beneficial if continued beyond the initial four to six cycles of chemotherapy. ECOG 5508, an ongoing phase III trial, will be the first trial to discontinue bevacizumab after using it in the induction phase and could give some clues to the incremental benefit, if any, of bevacizumab to maintenance therapy [35]. This trial will use PacCBev, not PemCBev, in the induction phase. The maintenance phase will be randomized to three arms: pemetrexed alone, bevacizumab alone, or the combination of pemetrexed and bevacizumab. In essence, this trial will compare two strategies that have been shown to improve OS for nonsquamous NSCLC—pemetrexed maintenance from JMEN and PARAMOUNT and bevacizumab induction and maintenance from ECOG 4599—and one strategy that has been shown to improve PFS—combination pemetrexed and bevacizumab maintenance from AVAPERL and PointBreak.

Optimal Maintenance Strategy: Which Is Best?

Ultimately, maintenance chemotherapy options depend on the choice for the initial treatment regimen and the preferred toxicity profile for each patient. For patients ineligible for bevacizumab because of comorbidities or age, maintenance pemetrexed is a logical choice based on strong data for improved OS. Switch or continuation maintenance therapy with pemetrexed has been shown to be effective at prolonging OS in several clinical trials (JMEN, PARAMOUNT) and can be given for prolonged periods of time with a manageable toxicity profile of fatigue and cytopenias for most patients. Switch maintenance has never been compared head to head with a continuation maintenance strategy for pemetrexed. Other trials have shown improvements in PFS (but not OS) for maintenance. Docetaxel (Fidias et al. [15]) or gemcitabine (CECOG and IFCT-GFPC 0502 trials [36, 37]) could also be considered, especially for patients with squamous NSCLC tumors.

For fit patients with nonsquamous NSCLC treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel, bevacizumab should be added, and maintenance bevacizumab is the logical choice. Its efficacy in the maintenance setting remains to be seen, particularly when added to pemetrexed maintenance. The combination maintenance trials of AVAPERL, PointBreak, and PRONOUNCE were unable to show an improvement in OS by combining pemetrexed and bevacizumab maintenance. At this time, either treatment from the PointBreak trial (PacCBev followed by bevacizumab or PemCBev followed by pemetrexed and bevacizumab) is a valid option for maintenance therapy for bevacizumab-eligible patients. It remains to be seen whether continuing bevacizumab after carboplatin, pemetrexed, and bevacizumab induction provides any additional benefit. Continuation of pemetrexed alone should be considered for patients with significant toxicity attributed to bevacizumab. The ECOG 5508 trial may provide additional information about the additive effects of bevacizumab to maintenance pemetrexed.

It remains to be seen whether continuing bevacizumab after carboplatin, pemetrexed, and bevacizumab induction provides any additional benefit. Continuation of pemetrexed alone should be considered for patients with significant toxicity attributed to bevacizumab.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines have included recommendations for maintenance chemotherapy for NSCLC, with various levels of evidence from category 1 for the highest level of evidence to 2B for lower levels of evidence with NCCN consensus [38]. Because of OS improvements in randomized phase III trials, continuation maintenance bevacizumab (ECOG 4599), pemetrexed (PARAMOUNT), and cetuximab (FLEX) have been given category 1 recommendations with the highest level of evidence for patients with nonsquamous NSCLC. Bevacizumab and pemetrexed combination maintenance has been given a category 2A recommendation based on PFS benefits seen in AVAPERL and PointBreak. Switch maintenance docetaxel (Fidias et al. [15]), pemetrexed (JMEN), and erlotinib (SATURN and IFCT-GFPC 0502) have category 2B recommendation based on criticisms of these trials, such as inconsistencies in postdiscontinuation therapy in control arms or lack of EGFR testing. Finally, maintenance gemcitabine has a category 2B recommendation for squamous and nonsquamous NSCLC based on the PFS improvements in the CECOG and IFCT-GFPC 0502 trials.

Conclusion

Many large clinical trials have been conducted in attempts to identify the best treatment strategy for patients with NSCLC. The addition of agents targeting VEGF, use of histology to guide chemotherapy decisions, and the addition of maintenance therapy have all shown incremental improvements in OS, particularly for nonsquamous histology. Targeting of EGFR in wild-type NSCLC has also resulted in some success in improving OS. Pemetrexed and bevacizumab have transformed treatment options for patients with nonsquamous NSCLC and, along with erlotinib, have recast the treatment paradigm to include well-tolerated maintenance therapies that extend survival for patients with NSCLC. No data support combination maintenance therapy as superior to single agent, but whether an optimal single agent exists is not clear. The authors favor choosing a platinum partner, typically pemetrexed or paclitaxel, based on the desired toxicity profile and adding bevacizumab unless contraindicated. The induction phase should be followed by maintenance bevacizumab for paclitaxel-based chemotherapy and maintenance pemetrexed or combination pemetrexed and bevacizumab maintenance for pemetrexed-based chemotherapy, providing the patient has stable or responsive disease and manageable toxicity after four cycles of platinum chemotherapy. The ECOG 5508 trial may help determine whether an incremental benefit with bevacizumab is possible when added to maintenance pemetrexed therapy.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Patrick M. Forde, Kim A. Reiss, Amer M. Zeidan et al. What Lies Within: Novel Strategies in Immunotherapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. The Oncologist 2013;18:1203–1213.

Implications for Practice: Immunotherapy, particularly the use of monoclonal antibodies that block inhibitory immune checkpoint molecules and thus enhance the immune response to tumor, has shown promise for advanced solid tumors, including non-small cell lung cancer, in recent years. We review the challenges and successes associated with harnessing the immune system to treat NSCLC using vaccine and immunomodulatory strategies and discuss recently reported data on durable responses to PD-1/PD-L1-directed therapies. Future directions in this rapidly evolving field are explored, including biomarker-driven strategies and combined treatments that have the potential to enhance cancer immunotherapy greatly.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Ryan D. Gentzler, Melissa L. Johnson

Provision of study material or patients: Ryan D. Gentzler, Melissa L. Johnson

Collection and/or assembly of data: Ryan D. Gentzler, Melissa L. Johnson

Data analysis and interpretation: Ryan D. Gentzler, Melissa L. Johnson

Manuscript writing: Ryan D. Gentzler, Melissa L. Johnson

Final approval of manuscript: Ryan D. Gentzler, Melissa L. Johnson

Disclosures

Melissa L. Johnson: Boehringer Ingelheim (C/A); Novartis (RF). The other author indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Park JO, Kim SW, Ahn JS, et al. Phase III trial of two versus four additional cycles in patients who are nonprogressive after two cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy in non small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5233–5239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hotta K, Matsuo K, Ueoka H, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing cisplatin to carboplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3852–3859. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:92–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subramanian J, Regenbogen T, Nagaraj G, et al. Review of ongoing clinical trials in non-small-cell lung cancer: A status report for 2012 from the ClinicalTrials.gov web site. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:860–865. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318287c562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gentzler RD, Yentz SE, Rademaker A, et al. Review of 10 years of ASCO abstracts for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and the impact of molecular biomarkers (MB) in clinical trial selection criteria. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:S890–S891. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2385–2394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramalingam SS, Dahlberg SE, Langer CJ, et al. Outcomes for elderly, advanced-stage non small-cell lung cancer patients treated with bevacizumab in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel: Analysis of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial 4599. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:60–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langer CJ, Socinski MA, Patel JD, et al. Efficacy and safety of paclitaxel and carboplatin with bevacizumab for the first-line treatment of patients with nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Analyses based on age in the phase III PointBreak and E4599 trials. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl):8073a. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciuleanu T, Brodowicz T, Zielinski C, et al. Maintenance pemetrexed plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care for non-small-cell lung cancer: A randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2009;374:1432–1440. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61497-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3543–3551. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quoix E, Zalcman G, Oster JP, et al. Carboplatin and weekly paclitaxel doublet chemotherapy compared with monotherapy in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: IFCT-0501 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1079–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60780-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zukin M, Barrios CH, Pereira JR, et al. Randomized phase III trial of single-agent pemetrexed versus carboplatin and pemetrexed in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 2. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2849–2853. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fidias PM, Dakhil SR, Lyss AP, et al. Phase III study of immediate compared with delayed docetaxel after front-line therapy with gemcitabine plus carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:591–598. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paz-Ares LG, de Marinis F, Dediu M, et al. PARAMOUNT: Final overall survival results of the phase III study of maintenance pemetrexed versus placebo immediately after induction treatment with pemetrexed plus cisplatin for advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2895–2902. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, et al. Erlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:521–529. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): An open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:121–128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:735–742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han JY, Park K, Kim SW, et al. First-SIGNAL: First-line single-agent Iressa versus gemcitabine and cisplatin trial in never-smokers with adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1122–1128. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3327–3334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pirker R, Pereira JR, Szczesna A, et al. Cetuximab plus chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (FLEX): An open-label randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1525–1531. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynch TJ, Patel T, Dreisbach L, et al. Cetuximab and first-line taxane/carboplatin chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of the randomized multicenter phase III trial BMS099. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:911–917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thatcher N, Hirsch FR, Szczesna A, et al. A randomized, multicenter, open-label, phase III study of gemcitabine-cisplatin (GC) chemotherapy plus necitumumab (IMC-11F8/LY3012211) versus GC alone in the first-line treatment of patients (pts) with stage IV squamous non-small cell lung cancer (sq-NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl):8008a. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel JD, Hensing TA, Rademaker A, et al. Phase II study of pemetrexed and carboplatin plus bevacizumab with maintenance pemetrexed and bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3284–3289. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barlesi F, Scherpereel A, Rittmeyer A, et al. Randomized phase III trial of maintenance bevacizumab with or without pemetrexed after first-line induction with bevacizumab, cisplatin, and pemetrexed in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAPERL (MO22089) J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3004–3011. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.3749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rittmeyer A, Scherpereel A, Gorbunova VA, et al. Effect of maintenance bevacizumab (Bev) plus pemetrexed (Pem) after first-line cisplatin/Pem/Bev in advanced nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer (nsNSCLC) on overall survival (OS) of patients (pts) on the AVAPERL (MO22089) phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl):8014a. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.3749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson BE, Kabbinavar F, Fehrenbacher L, et al. ATLAS: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase IIIB trial comparing bevacizumab therapy with or without erlotinib, after completion of chemotherapy, with bevacizumab for first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3926–3934. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.3983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel JD, Socinski MA, Garon EB, et al. PointBreak: A randomized phase III study of pemetrexed plus carboplatin and bevacizumab followed by maintenance pemetrexed and bevacizumab versus paclitaxel plus carboplatin and bevacizumab followed by maintenance bevacizumab in patients with stage IIIB or IV nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4349–4357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.9626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zinner R, Ross HJ, Weaver R, et al. Randomized, open-label, phase III study of pemetrexed plus carboplatin (PemC) followed by maintenance pemetrexed versus paclitaxel/carboplatin/bevacizumab (PCB) followed by maintenance bevacizumab in patients with advanced nonsquamous (NS) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl):LBA8003a. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel JD, Socinski MA, Garon EB, et al. A randomized, open-label, phase 3, superiority study of pemetrexed (Pem)+carboplatin (Cb)+bevacizumab (B) followed by maintenance Pem+B versus paclitaxel (Pac)+Cb+B followed by maintenance B in patients (pts) with stage IIIb or IV non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (ns-NSCLC) J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:S336–S338. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000277. [abstract LBPL331] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Socinski MA, Bondarenko I, Karaseva NA, et al. Weekly nab-paclitaxel in combination with carboplatin versus solvent-based paclitaxel plus carboplatin as first-line therapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Final results of a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2055–2062. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson DH, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny WF, et al. Randomized phase II trial comparing bevacizumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2184–2191. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dahlberg SE, Ramalingam SS, Belani CP, et al. A randomized phase III study of maintenance therapy with bevacizumab (B), pemetrexed (Pm), or a combination of bevacizumab and pemetrexed (BPm) following carboplatin, paclitaxel and bevacizumab (PCB) for advanced nonsquamous NSCLC: ECOG trial 5508 ( NCT01107626) J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl):TPS218a. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pérol M, Chouaid C, Pérol D, et al. Randomized, phase III study of gemcitabine or erlotinib maintenance therapy versus observation, with predefined second-line treatment, after cisplatin-gemcitabine induction chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3516–3524. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.9782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brodowicz T, Krzakowski M, Zwitter M, et al. Cisplatin and gemcitabine first-line chemotherapy followed by maintenance gemcitabine or best supportive care in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A phase III trial. Lung Cancer. 2006;52:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Non-small cell lung cancer (version 3.2014). Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf. Accessed April 24, 2014.