Abstract

Introduction

We report a case of an adult patient with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP) caused by multidrug resistant (MDR) bacteria that was successfully managed with veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

Case report

A 25 year old male with no significant past medical history had been admitted to a local hospital due to dyspnea and fever. His pulmonary function subsequently failed necessitating mechanical ventilation (MV) and introduction of ECMO support. The patient was transported for 300 km by road on ECMO to a tertiary medical center. The diagnosis of ARDS, HIV infection and MDR bacterial and fungal VAP was made. Patient was successfully treated with antiretroviral therapy (ART), anti-infective agents and 58 days of veno-venous ECMO support, with complete resolution of the respiratory symptoms.

Conclusion

HIV infected patients with ARDS and MDR bacterial VAP whose HIV replication is controlled by ART could be successfully managed with ECMO.

Keywords: HIV, veno-venous ECMO, ARDS, multidrug resistant bacteria, VAP

Background

According to Berlin definition [1] acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is characterized by 1) lung injury of acute onset, within 1 week of an apparent clinical insult and with progression of respiratory symptoms; 2) bilateral opacities on chest imaging not explained by other pulmonary pathology (e.g. pleural effusion, pneumothorax, or nodules); 3) respiratory failure not explained by heart failure or volume overload; 4) mechanical ventilation with decreased PaO2/FiO2 (ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen).

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is salvage therapy for selected group of patients with gas-exchange failure refractory to mechanical ventilation (MV). Severe hypoxemia despite the application of high levels of PEEP or uncompensated hypercapnia are the main indications for ECMO treatment. Mechanical ventilation at high settings (FiO2 90%, Pplat >30 mmHg) for more than 7 days, immunosupression and intracranial hemorrhage are the main contraindications for using this mode of treatment. ECMO is associated with considerable risks for the patient, including but not limited to bleeding, infection or mechanical failure of the ECMO circuit [2]. Recently, ECMO has been shown to be very effective in treating ARDS patients during H1N1 pandemic [3] and successful use of ECMO in immunocompromised patients has been reported [4, 5]. However, it remains a relative contraindication to extracorporeal life support.

The purpose of this report is to describe an human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected patient with ARDS complicated by multidrug resistant (MDR) bacterial and fungal ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP) who was successfully managed with veno-venous ECMO and off-label doses of antimicrobial agents.

Case presentation

A 25 year old male with no significant past medical history was admitted to a local hospital due to dyspnea and fever of 39°C. The patient’s pulmonary computer tomography (CT) scan was consistent with alveolitis. Sputum and blood cultures were negative. Patient received empirical Amoxicillin prior to hospitalisation and Cefuroxime in hospital without any improvement. For suspected allergic alveolitis prednisolone 40 mg daily for 8 days was administered. As a result of worsening of respiratory function on day 10 of initial hospitalization, the patient was transferred to intensive care unit (ICU). 1 gram of methylprednisolone once, followed by three consecutive doses of 120 mg/per day were administered. Pulmonary function deteriorated and mechanical ventilation was initiated on day 6 in intensive care unit stay. No signs of any other organ system dysfunction were evident. Antibiotic therapy was changed to Imipenem and Vancomycine. On day 11 of MV, the patient’s respiratory function deteriorated substantially. The decision was made to transfer the patient to Vilnius University Hospital Santariskiu Klinikos (VUHSK) with facilities for ECMO treatment.

When transport team arrived, tidal volume was decreasing to critical levels trying to achieve safe ventilation pressures, the patient had drained pneumothorax, paO2/FiO2 of 84 mmHg on 85% of FiO2 and 16 cm H2O of PEEP. As well patient had permissive hypercapnia with CO2 of 87 mmHg; Murray score was 4 (up to four points in each of four categories; PaO2/FiO2, number of quadrants with alveolar consolidation, PEEP, and compliance) [6]; pulmonary compliance was only 4 ml/cm H2O; with pressure control ventilation of 30 cm H2O the inspired tidal volume was only 2 ml/kg. The decision was made to place the patient on veno-venous ECMO before the transfer because paO2/FiO2 of less than 80 mmHg on 90% of FiO2 and Murray score of 3–4 identifies the risk of mortality of 80% with conventional treatment and is an indication for initiation of extracorporeal life support according to the extracorporeal life support organization guidelines (http://www.elso.med.umich.edu/Guidelines.html). 23 French drainage cannula (Bio-Medicus, Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, USA) was inserted percutaneously into inferior vena cava via femoral approach and 19 French return cannula was inserted into the left internal jugular vein. ECMO circuit consisted of bioline coated Quadrox PLS oxygenator and Rotaflow centrifugal pump (Maquet Cardiopulmonary AG, Rastatt, Germany). The patient was uneventfully transported for 300 km (200 minutes) by road ambulance to VUHSK, ECMO flow was 6 l/min.

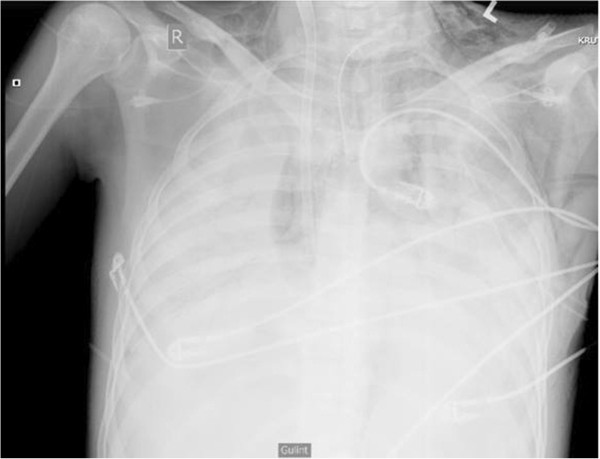

On admission to VUHSK, the patient’s lung compliance was 3–4 ml/cm H2O, his respiratory tidal volume was only 1–2 mL/kg to keep the ventilation pressure safe at <30 cm H2O. The patient had lung infiltration of 4 quadrants seen on chest x-ray (Figure 1). The white blood cell (WBC) count was 8.72 × 109/L (neutrophils 7.71 × 109/L, lymphocytes 0.66 × 109/L), platelets 257 × 109/L, hemoglobin 109 g/l, lactate 1.36 mmol/L and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 93 mg/L. On the first day at VUHSK, the patient was confirmed HIV positive (positive anti-HIV ½ Ag/Ab, Western Blot analysis showed three bands (p41, gp120 and p51) and HIV-1 RNA was 2.22 million copies/mL), his CD4 cell count was 134 cells/μL. The blood sample was positive for CMV DNA (442420 copies/mL). The bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid WBC count was 1.17 × 109/L (99% neutrophils) and was positive for CMV DNA (76740 copies/mL), Candida glabrata and MDR Acinetobacter baumanii. The diagnosis of ARDS, HIV infection, nosocomial VAP and possible CMV pneumonitis was made. Colistin, Linezolid, Imipenem, Ganciclovir and Anidulafungin were started. ART consisting of Kivexa (Abacavir and Lamivudine) and Kaletra (Lopinavir and Ritonavir) was initiated. The patient was continued with MV, full intensive care and intermittent vasopressor support. Blood flow during ECMO was tailored to achieve acceptable oxygenation. Ventilator settings were reduced to protective ventilation mode. During the ICU stay, aggressive treatment of numerous nosocomial infections was required (Table 1). Complications during ECMO are detailed in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Chest x- ray on admission at VUHSK (3 hours after ECMO start) .

Table 1.

Nosocomial infections and treatment

| ICU day | Bacteria | Fungus | Virus | CRP, mg/L | Treatment | MIC, mg/L | Administration route | Daily dose | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acinetobacter baumanii* | Pseudomonas aeruginosa** | Pseudomonas fluorescens | Enterobacter aerogenes | Candida glabrata | Candida parapsilosis | Cytomegalovirus (CMV) | ||||||

| 1 | BAL/CAT | BAL/CAT | BAL/BL | 93 | Colistin | 1 | i.v. | 13.5 m. IU | ||||

| Ganciclovir | - | i.v. | 0.8 g | |||||||||

| 3 | SP | 165 | Colistin | 1 | i.v. | 13.5 m. IU | ||||||

| 8 | BAL | 77 | Anidulafungin | 0.125 | i.v. | 0.1 g | ||||||

| 11 | BAL | 151 | Colistin | 1 | i.v. | 13.5 m. IU | ||||||

| 16 | BAL | 286 | Ciprofloxacin | 0.5 | i.v. | 1.2 g | ||||||

| 24 | BAL/BL | 22 | Ciprofloxacin | 0.5 | i.v. | 2.4 g | ||||||

| Colistin | 2 | i.v./inh | 13.5/6 m. IU | |||||||||

| 28, 35, 39 | BAL/ UR | 149-157 | Colistin | 0.5-2 | i.v./inh | 13.5/9 m. IU | ||||||

| 43 | BAL/UR | 162 | Ampicillin Sulbactam | 2 | i.v. | 36 g | ||||||

| 51 | BAL | 98 | Cefepim | 4 | i.v. | 6 g | ||||||

| 63 | BAL | 86 | Colistin | 0.5 | i.v./inh | 13.5/15 m. IU | ||||||

| 65, 70 | BL/ CAT | 73 | Amphotericin B | 0.5 | i.v. | 0.08 g | ||||||

| 75 | CAT | CAT | CAT | 90 | Ciprofloxacin | 0.38 | i.v. | 2.4 g | ||||

| Cefepim | 4 | i.v. | 6 g | |||||||||

| Imipenem | 1 | i.v. | 3 g | |||||||||

| Amphotericin B | 0.19 | i.v. | 0.08 g | |||||||||

| 77 | CAT | 108 | Imipenem | <0.25 | i.v. | 3 g | ||||||

ICU – intensive care unit, CRP – C-reactive protein, MIC – minimal inhibitory concentration, BL – blood, BAL – bronchoalveolar lavage, CAT – catheter, UR – urine, i.v. – intravenous, inh.–inhaled, m. – million, IU – international units.

*Acinetobacter baumanii was carbapenems (Imipenem, Meropenem MIC 32 mg/L), aminoglycosyde (Amikacin MIC 256 mg/L, Gentamycin MIC 24 mg/L) and cephalosporin (Cefepim MIC 48 mg/L) resistant;

**Pseudomonas aeruginosa was carbapenems (Meropenem MIC 32 mg/L), cephalosporin (Cefepim MIC 12 mg/L) resistant.

Table 2.

Complications and their treatment during ECMO

| ICU day | Complications | Treatment/Procedures |

|---|---|---|

| 1- 59 | Bilateral pneumothorax | Pleural cavity drainage |

| 25, 31, 51 | Pulmonary hemorrhage | Endobroncheal hemostasis |

| 38 | Tilt of left jugular vein cannula with blood loss of 2 liters | Cannula reinserted, transfusions of packed red blood cells and platelets |

| 46 | Blood-clot masses in pleural cavity | Open right side thoracotomy with clot removal and lung decortication |

| 48 | Left side tension pneumothorax with cardiogenic shock | Pleural cavity drainage, resuscitation |

| 52 | Bleeding from tracheostoma | Endobroncheal hemostasis |

| Endrobronchial clot-masses | Bronchoscopy and clot-mass removal | |

| 60 | Cannula associated deep vein thrombosis | Heparin, compression therapy |

Despite aggressive treatment, improvement of pulmonary mechanics was slow (tidal volume with Ppeak 30 cm H2O was only up to 2 ml/kg, compliance remained at 1–4 ml/cm H2O). For the downregulation of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg/dose per day for 7 days was administered on ECMO day 18 and then gradually tapered off over 15 days. This resulted in improved lung function (tidal volume increased to 4.4 mL/kg with Ppeak 27 cmH2O and compliance 9–10 ml/cm H2O).

The first oxygenator was exchanged on day 38 after decrease in function. The patient was weaned off ECMO after 56 days. Unfortunately, 48 hours later, acute hypercapnic respiratory failure developed (pCO2 190 mmHg, pH 7.05). The veno-venous ECMO was reinstituted with successful weaning after 48 hours. MV was continued for additional 18 days.

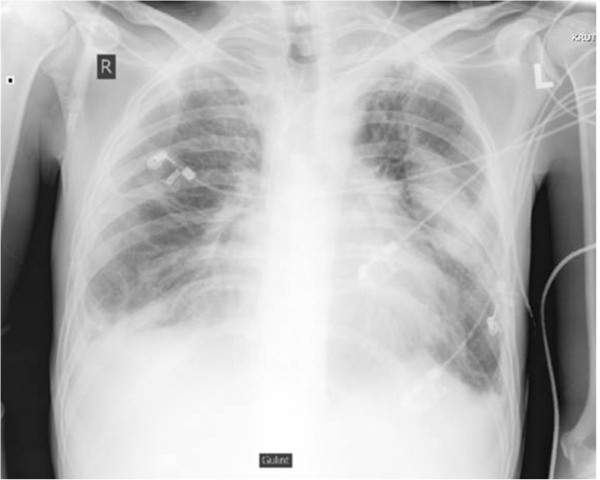

After 70 days of ART, the patient’s CD4 cell count increased to 268 cells/μL and the HIV-1 viral load became 591 copies/mL, lung chest X-ray is shown in Figure 2. The patient was transferred to a general ward and later discharged from hospital to continue rehabilitation. At the last clinic visit 115 days after having been discharged from ICU, the patient reported good health, had no pulmonary symptoms, could walk unassisted for more than 2 kilometers.

Figure 2.

Chest x- ray after weaning off ECMO.

In total, 51 packed red blood cells and 14 platelet units were transfused. The total duration of ECMO was 58 days. The total MV duration was 87 days (11 pre ECMO, 58 ECMO and 18 post ECMO). The total VUHSK ICU stay was 84 days.

Discussion

ECMO use in immunocompromised patients is controversial because of high mortality [7–9]. To the best of our knowledge, there is only one report of ECMO use in HIV infected patient [5]. We had not been aware of the patient’s HIV infection and thus were not biased when deciding to initiate ECMO support. Also, our patient may have had an early stage of HIV infection as witnessed by a high HIV-1 viral load in parallel with a weak antibody band spectrum on Western Blot analysis and relatively rapid CD4 count recovery.

Importantly, our patient had a predominant pulmonary failure while the function of other organs was relatively preserved making veno-venous ECMO a good choice of gas-exchange support while anti-infective therapy took effect. Also, we chose an aggressive preemptive approach to diagnose and treat nosocomial superinfections. Increased cardiac output, leaky capillaries, enlarged volume of distribution and impaired tissue penetration in septic patients may lead to an inadequate concentration of antimicrobial agent at the target site [10]. Also, due to sequestration and increased volume of distribution patients on ECMO are at risk of suboptimal antimicrobial therapy [11]. Therefore, there is a tendency to use higher doses of antimicrobial agents in critically ill patients. In our case, antibiotics were changed as soon as nosocomial bacteria were identified at doses that in many cases were considerably higher (Table 1) [12–14] than indicated in the drug label. We did not observe unacceptable antibiotic related toxicity.

ART was initiated as soon as HIV positivity was confirmed. Of note, ART suppresses HIV replication and may cause immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome [15]. We administered a short course of methylprednisolone resulting in improved lung function. A recent meta-analysis showed a possibility of reduced mortality and increased ventilator free days with steroids in ARDS [16].

Common complications during ECMO are pneumonia, sepsis and bleeding especially associated with invasive procedures [17]. In our case, pulmonary hemorrhage, bleeding from the cannulation site and pneumothorax (including one case of tension pneumothorax) were observed necessitating surgical and medical intervention (Table 2). After first weaning off ECMO we observed hypercapnic respiratory failure leading to hemodynamic instability. This emphasizes uneven pulmonary gas exchange reconstitution with CO2 exchange recovery often trailing that of O2 [18].

Conclusions

In individual cases, ECMO could be succesfully applied in HIV infected patients with ARDS refractory to conventional treatment and ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by multidrug resistant bacteria whose HIV replication is controlled by antiretroviral therapy. Long-distance transportation on ECMO may be attempted in selected cases.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- ART

Antiretroviral therapy

- BAL

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- CRP

C – reactive protein

- CT

Computer tomography

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- ECMO

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- IRIS

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome

- MDR

Multidrug resistant

- MV

Mechanical ventilation

- PEEP

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- VAP

Ventilator associated pneumonia

- VUHSK

Vilnius University Hospital Santariskiu Klinikos

- WBC

White blood cell.

Footnotes

Competing interests

All the authors declare that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Authors’ contributions

RS: and MS were leading members of ECMO team and were responisble for ECMO care during treatment in ICU. DR: DG and JS: – preeminent reanimatologists who were responsible for main treatment during patients stay in ICU. RB: BR: – were responsible for data collection, analysis and drafting the manuscript. RM: – infectologist, responsible for ART and further patients’ HIV status monitoring. RA: TK: – clinical microbiologist, responsible for blood, bronchial BAL: urine and catheter culture analysis, tracking the sensitivity of antibiotics and MIC’s. LG: – principal investigator, manuscript revisor. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Robertas Samalavicius, Email: robertas.samalavicius@santa.lt.

Mindaugas Serpytis, Email: mindaugas.serpytis@santa.lt.

Donata Ringaitiene, Email: donata.ringaitiene@santa.lt.

Daiva Grazulyte, Email: daiva.grazulyte@santa.lt.

Ruta Bertasiute, Email: ruta.bertasiute@santa.lt.

Bernardas Rimkus, Email: bernardas.rimkus@santa.lt.

Raimonda Matulionyte, Email: raimonda.matulionyte@santa.lt.

Ruta Ambrazaitiene, Email: ruta.ambrazaitiene@santa.lt.

Jurate Sipylaite, Email: jurate.sipylaite@santa.lt.

Tomas Kacergius, Email: tomas.kacergius@mf.vu.lt.

Laimonas Griskevicius, Email: laimonas.griskevicius@santa.lt.

References

- 1.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peek GJ, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, Wilson A, Allen E, Thalanany MM, Hibbert CL, Truesdale A, Clemens F, Cooper N, Firmin RK, Elbourne D. Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1351–1363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies A, Jones D, Bailey M, Beca J, Bellomo R, Blackwell N, Forrest P, Gattas D, Granger E, Herkes R, Jackson A, McGuinness S, Nair P, Pellegrino V, Pettila V, Plunkett B, Pye R, Torzillo P, Webb S, Wilson M, Ziegenfuss M, Australia, New Zealand Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Influenza I Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for 2009 Influenza A(H1N1) Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. JAMA. 2009;302:1888–1895. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liao WI, Tsai SH, Chiu SK. Successful use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a hematopoietic stem cell transplant patient with idiopathic pneumonia syndrome. Respir Care. 2013;58:e6–e10. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutermann H, van Roy B, Meersseman W, Meyns B, Herijgers P. Successful extracorporeal lung assistance for overwhelming pneumonia in a patient with undiagnosed full blown aids–a controversial therapy in HIV-patients. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;53:252–254. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray JF, Matthay MA, Luce JM, Flick MR. An expanded definition of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:720–723. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.3.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Lelyveld SF, Wind CM, Mudrikova T, van Leeuwen HJ, de Lange DW, Hoepelman AI. Short- and long-term outcome of HIV-infected patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:1085–1093. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1196-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt M, Zogheib E, Roze H, Repesse X, Lebreton G, Luyt CE, Trouillet JL, Brechot N, Nieszkowska A, Dupont H, Ouattara A, Leprince P, Chastre J, Combes A. The PRESERVE mortality risk score and analysis of long-term outcomes after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1704–1713. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3037-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hermans G, Meersseman W, Wilmer A, Meyns B, Bobbaers H. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: experience in an adult medical ICU. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;55:223–228. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-955942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts JA, Lipman J. Pharmacokinetic issues for antibiotics in the critically ill patient. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:840–851. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181961bff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shekar K, Roberts JA, Ghassabian S, Mullany DV, Wallis SC, Smith MT, Fraser JF. Altered antibiotic pharmacokinetics during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: cause for concern? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:726–727. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vicari G, Bauer SR, Neuner EA, Lam SW. Association between colistin dose and microbiologic outcomes in patients with multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:398–404. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michalopoulos AS, Falagas ME. Colistin: recent data on pharmacodynamics properties and clinical efficacy in critically ill patients. Crit Care Resusc. 2011;1:30. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-1-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falagas ME, Rafailidis PI, Ioannidou E, Alexiou VG, Matthaiou DK, Karageorgopoulos DE, Kapaskelis A, Nikita D, Michalopoulos A. Colistin therapy for microbiologically documented multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections: a retrospective cohort study of 258 patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akgun KM, Pisani M, Crothers K. The changing epidemiology of HIV-infected patients in the intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2011;26:151–164. doi: 10.1177/0885066610387996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peter JV, John P, Graham PL, Moran JL, George IA, Bersten A. Corticosteroids in the prevention and treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in adults: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:1006–1009. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39537.939039.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zangrillo A, Landoni G, Biondi-Zoccai G, Greco M, Greco T, Frati G, Patroniti N, Antonelli M, Pesenti A, Pappalardo F. A meta-analysis of complications and mortality of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care Resusc. 2013;15:172–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Artigas A, Bernard GR, Carlet J, Dreyfuss D, Gattinoni L, Hudson L, Lamy M, Marini JJ, Matthay MA, Pinsky MR, Spragg R, Suter PM. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS, part 2. Ventilatory, pharmacologic, supportive therapy, study design strategies and issues related to recovery and remodeling. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24:378–398. doi: 10.1007/s001340050585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]