Abstract

Background/Aims

CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP)- high colorectal cancers (CRCs) have distinct clinicopathological features from their CIMP-low/negative CRC counterparts. However, controversy exists regarding the prognosis of CRC according to the CIMP status. Therefore, this study examined the prognosis of Korean patients with colon cancer according to the CIMP status.

Methods

Among a previous cohort population with CRC, a total of 154 patients with colon cancer who had available tissue for DNA extraction were included in the study. CIMP-high was defined as 3/5 methylated markers using the five-marker panel (CACNA1G, IGF2, NEUROG1, RUNX3, and SOCS1).

Results

CIMP-high and CIMP-low/negative cancers were observed in 27 patients (17.5%) and 127 patients (82.5%), respectively. Multivariate analysis adjusting for age, gender, tumor location, tumor stage and CIMP and microsatellite instability (MSI) statuses indicated that CIMP-high colon cancers were associated with a significant increase in colon cancer-specific mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 3.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20 to 8.69; p=0.02). In microsatellite stable cancers, CIMP-high cancer had a poor survival outcome compared to CIMP-low/negative cancer (HR, 2.91; 95% CI, 1.02 to 8.27; p=0.04).

Conclusions

Regardless of the MSI status, CIMP-high cancers had poor survival outcomes in Korean patients.

Keywords: Colonic neoplasms, CpG island methylator phenotype, Survival outcome

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of most common malignancies in the world and the third leading cause of cancer death (approximately 10% of cancer deaths overall).1 The causes of colorectal tumorigenesis are both environmental and genetic. The genetic and epigenetic instability pathways that drive colon neoplasia are known to be chromosomal instability, microsatellite instability (MSI) caused by defects in DNA mismatch-repair genes that are either inherited as germ-line defects or somatically acquired, and the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP).2,3 The role of CIMP is controversial because it is unclear if aberrant DNA methylation is the initiating event of colorectal tumorigenesis or if the silencing promoter is induced by another mechanism and methylation is a secondary result. However, aberrant DNA methylation of CpG islands is observed widely in colorectal cancer and has been closely linked with gene silencing when it occurs in the promoter areas.4,5 Recent research showed that hypermethylation of the promoter areas plays an important role in colorectal tumorigenesis.6,7

CIMP-high CRCs have been reported to have a different clinicopathological features from their CIMP-low/negative CRC counter parts; older age, female gender, proximal tumor location, poorly differentiated or mucinous histology, and high rates of MSI and BRAF mutation.7–13

Several studies showed that CIMP-high CRCs have a poor prognosis according to the microsatellite stable (MSS) or BRAF mutation.6,14,15 However, another study showed that patients with CIMP-low had a poor prognosis regardless of the MSI screening status.16 One large study demonstrated that CIMP-high CRCs were associated with a significant decrease in colon cancer-specific mortality, regardless of both the MSI and BRAF status.17 Therefore, there is some controversy regarding the prognosis of CRCs according to the CIMP status. These may originate from the different patient cohorts, different methylation panels, and other clinicopathological confounding factors. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the effect of the CIMP status on the survival outcome and the disease-free survival of CRC patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study population

Among 523 CRC patients enrolled in the previous cohort study,18 a total of 154 patients with tissue samples available for DNA extraction were enrolled in this study. First, patients with rectal cancer (239/523, 46%) were excluded due to the possibility of tumor characteristic change by neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Secondly, 130 colon cancer patients (24.9%) were also excluded due to unavailable DNA extraction from lack of paraffin-embedded tissues. The stage was defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer.19 The clinicopathological data including age, gender, tumor location, tumor stage, and histological differentiation were obtained by reviewing the medical records and pathology slides of the enrolled cases.

Based on splenic flexure, the tumors located from the cecum to the transverse colon were classified as proximal tumors and those from the splenic flexure to the rectum were classified as distal tumors. The patients’ colon cancer-specific mortality was observed by the medical records in hospital. The colon cancer-specific survival was measured from the date of the resection to the date of death by the national insurance system or until the censoring date of May 31, 2010 to check the 5-year follow-up.

The disease-free survival was initiated from the beginning date of surgery. The event endpoint of the disease-free survival was the first recurrence documented by imaging or pathological confirmation or until the censoring date of May 31, 2010.

All the patients provided informed consent prior to specimen collection according to the institutional guidelines.

2. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction to measure DNA methylation (MethyLight)

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were used for DNA extraction. Ten sections of 10-μm thick paraffin-embedded tissues were used for DNA extraction. One gastrointestinal pathologist (K.M.K.) reviewed all slides of the dissected tissues and DNA extraction was used the slides containing only cancer tissues. The paraffin was removed from the tissue by rinsing in xylene, and the genomic DNA was isolated using a QIAamp tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Bisulfite conversion was performed using the Zymo EZ DNA methylation kit (Zymo Research Co., Orange, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After bisulfite conversion of the same amount of the DNA solution, an ALU-based MethyLight control reaction was performed to quantify the number of input target DNA, and the threshold cycle values were confirmed to be comparable between DNA samples. A MethyLight assay to measure the DNA methylation of seven individual genes was performed as reported previously.7,20 Supplementary Table 1 lists the primers and probes specific to methylated DNA and used for the MethyLight reactions. The percentage of the methylated reference (PMR) at a specific gene was calculated by dividing the GENE/ALU ratio of a sample by the GENE/ALU ratio of in vitro fully methylated placental DNA and multiplying by 100. The DNA methylation frequencies (PMR >10) were determined for each CpG island locus. CIMP-high was defined as ≥3/5 methylated markers using the five-marker panel, and CIMP-low and CIMP-negative as ≤2/5 methylated markers. Dr Laird’s five panels (CACNA1G, IGF2, NEUROG1, RUNX3, and SOCS1) for the CIMP marker panel were used.7

3. MSI analysis

The five microsatellite markers recommended by the National Cancer Institute Workshop (BAT 25, BAT26, D5S346, D17S250, and D2S124) were used to define the MSI status.21 The tumors were designated as high MSI tumors (instability ≥2 microsatellite loci) and microsatellite-stable tumors (instability ≤1 microsatellite loci). For the cases where the tumors (n=50) could not match the normal tissues due to the unavailability of tissue specimens, the MSI status was determined based on the monomorphic nature of BAT 26, which is a simple and rapid method for screening the MSI without matching the normal DNA.22,23

4. Statistical analysis

The colon cancer-specific survival curves and disease-free survival were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was performed to evaluate the differences between the individual curves. Cox proportional hazard models were analyzed to calculate the hazard ratios [HRs] of death according to the CIMP status in colon cancer, adjusted for age, gender, tumor stage, tumor location, lymph node metastasis and tumor histology. Each categorical variable and continuous variable of the clinicopathological features was calculated using a chi-square test and Student t-test. p-values ≤0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

1. Clinical and molecular features

Table 1 lists the baseline characteristics according to the CIMP status. Among the colon cancers, CIMP-high cancers and CIMP-low/negative cancers were found in 27 cases (17.5%) and 127 cases (82.5%), respectively. The median age (range) in the CIMP-high and CIMP-low/negative were 61 years (41 to 79 years) and 60 years (34 to 85 years), respectively. There was some relationship with female gender and proximal location in CIMP high cancer, but this was not statistically significant. The incidence of an undifferentiated histology and MSI-high is not found frequently in CIMP-high colon cancers. Clinicopathological analysis of the MSS tumor showed that age, gender, tumor location, tumor histology, tumor stage, and lymph node metastasis were not associated with CIMP-high tumors or CIMP-low/negative tumors (Table 2).

Table 1.

Clinicopathological Features of Colon Cancers according to CpG Island Methylation Phenotype Status

| CIMP-high (n=27) | CIMP-low/negative (n=127) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), yr | 61 (41–79) | 60 (34–85) | 0.57 |

| Male sex | 14 (52) | 82 (65) | 0.18 |

| Tumor location | 0.09 | ||

| Proximal | 17 (63) | 57 (45) | |

| Distal | 10 (37) | 70 (55) | |

| Histological type | 0.72 | ||

| Differentiated | 22 (82) | 107 (84) | |

| Undifferentiated | 5 (18) | 20 (16) | |

| Tumor stage | 0.50 | ||

| I | 2 (7) | 16 (13) | |

| II | 13 (48) | 55 (43) | |

| III | 8 (30) | 45 (35) | |

| IV | 4 (15) | 11 (9) | |

| LN metastasis | 0.57 | ||

| Yes | 12 (44) | 49 (39) | |

| No | 15 (56) | 78 (61) | |

| MSI | 0.83 | ||

| MSI-H | 2 (7) | 11 (9) | |

| MSS | 25 (93) | 116 (91) |

Data are presented as number (%).

CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype; LN, lymph node; MSI-H, high microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stable.

Table 2.

Clinicopathological Features of Microsatellite Stable Colon Cancers according to CpG Island Methylator Phenotype Status

| CIMP-high (n=25) | CIMP-low/negative (n=116) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), yr | 58 (41–79) | 60 (34–85) | 0.95 |

| Male sex | 13 (52) | 76 (66) | 0.20 |

| Tumor location | 0.09 | ||

| Proximal | 15 (60) | 48 (41) | |

| Distal | 10 (40) | 68 (59) | |

| Histological type | 0.77 | ||

| Differentiated | 21 (84) | 100 (86) | |

| Undifferentiated | 4 (16) | 16 (14) | |

| Tumor stage | 0.54 | ||

| I | 2 (8) | 16 (14) | |

| II | 12 (48) | 47 (40) | |

| III | 7 (28) | 43 (37) | |

| IV | 4 (16) | 10 (9) | |

| LN metastasis | 0.75 | ||

| Yes | 11 (44) | 47 (41) | |

| No | 14 (56) | 69 (59) |

Data are presented as number (%).

CIMP, CpG island methylation phenotype; LN, lymph node.

2. Colon cancer-specific survivals and disease-free survivals

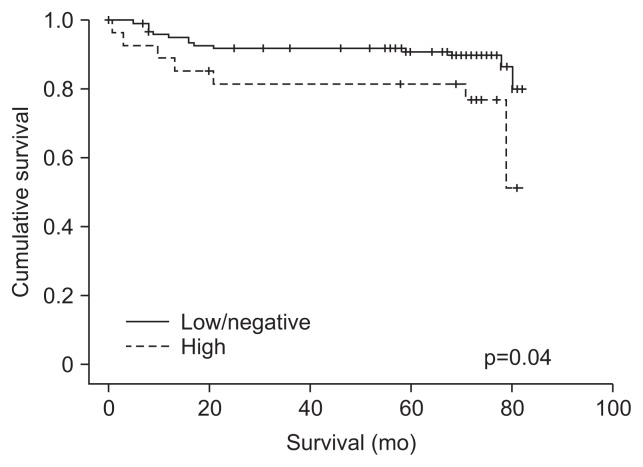

Fig. 1 shows the survival curves based on the CIMP status using the Kaplan-Meier method. CIMP-high tumors demonstrated a poor clinical outcome compared to the outcome of CIMP-low/negative tumors (p=0.04, log-rank test). Univariate analyses between the clinicopathological factors and the cancer-specific survival of colon cancers revealed higher tumor stage, the presence of lymph node metastasis, and CIMP-high to be factors associated with a poor prognosis (Table 3). Multivariate analysis revealed colon cancers with CIMP-high to be associated with a significant increase in colon cancer-specific mortality (HR, 3.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20 to 8.69; p=0.02).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of the likelihood of survival from colon cancer according to the status of the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP). CIMP-high (n=27), CIMP-low/negative (n=127).

Table 3.

Relationship between Clinicopathological Factors and Colon Cancer-Specific Survival of Colon Cancer

| All sporadic colon cancer HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||

| Age (<60 yr vs ≥60 yr) | 1.21 (0.51–2.87) | 0.67 |

| Sex (male vs female) | 1.07 (0.44–2.58) | 0.88 |

| Tumor location (right vs left) | 1.21 (0.51–2.84) | 0.67 |

| Histologic type (differentiated vs undifferentiated) | 1.14 (0.38–3.40) | 0.82 |

| Tumor stage (I, II vs III, IV) | 15.60 (3.63–67.13) | <0.01 |

| LN metastasis (negative vs positive) | 7.82 (2.62–23.35) | <0.01 |

| CIMP (low/negative vs high) | 2.50 (1.00–6.23) | <0.05 |

| MSI (MSS vs MSI-H ) | 0.84 (0.19–3.69) | 0.82 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||

| CIMP (low/negative vs high) | 3.23 (1.20–8.69) | 0.02 |

| Tumor stage (I, II vs III, IV) | 47.11 (3.61–431.47) | 0.01 |

Multivariate analysis using a Cox proportional hazards model includes age, gender, tumor location, stage and CIMP and MSI statuses.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; LN, lymph node; CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype; MSI, microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stable; MSI-H, high microsatellite instability.

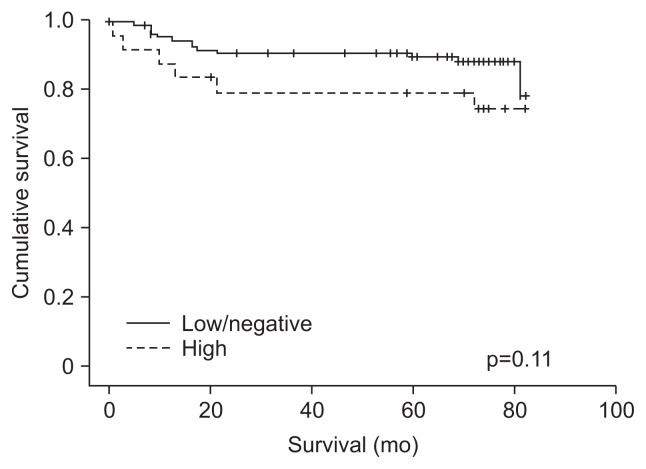

The colon cancer-specific survival could not be analyzed according to the four molecular subgroups (CIMP-high/MSI-high, CIMP-high/MSS, CIMP-low&negative/MSI-high, CIMP-low&negative/MSS) due to small sample size (CIMP-high/MSI-high, 2/154, 1.2%). Therefore, the survival curve of MSS tumor was analyzed according to CIMP status except for MSI-high tumors (Fig. 2). Univariate analysis of the MSS tumor according to the CIMP status revealed a poor survival outcome of patients with a higher tumor stage and lymph node metastasis. Multivariate analysis adjusted for age, gender, tumor location, tumor histology, and tumor stage, revealed MSS colon cancer with CIMP-high to have a poor survival outcome compared to MSS colon cancer with CIMP-low/negative (HR, 2.91; 95% CI, 1.02 to 8.27; p=0.04) (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of the likelihood of survival of microsatellite stable colon cancer according to the status of the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP). CIMP-high (n=25), CIMP-low/negative (n=116).

Table 4.

Relationship between Clinicopathological Factors and Colon Cancer-Specific Survival of Microsatellite Stable Colon Cancer

| All sporadic colon cancer HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||

| Age (<60 yr vs ≥60 yr) | 1.06 (0.43–2.61) | 0.90 |

| Sex (male vs female) | 1.00 (0.40–2.55) | 0.99 |

| Tumor location (right vs left) | 1.48 (0.60–3.63) | 0.40 |

| Histologic type (differentiated vs undifferentiated) | 0.74 (0.17–3.21) | 0.69 |

| Tumor stage (I, II vs III, IV) | 12.98 (2.99–56.30) | <0.01 |

| LN metastasis (negative vs positive) | 6.08 (2.01–18.35) | <0.01 |

| CIMP (low/negative vs high) | 2.16 (0.82–5.67) | 0.12 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||

| CIMP (low/negative vs high) | 2.91 (1.02–8.27) | 0.04 |

| Tumor stage (I, II vs III, IV) | 65.94 (7.29–592.66) | <0.01 |

Multivariate analysis using a Cox proportional hazards model includes age, gender, tumor location, stage and status of CIMP.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; LN, lymph node; CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype.

An analysis of the disease-free survival using Kaplan-Meier method revealed no significant difference between CIMP-high tumors and CIMP-low/negative tumors (p=0.39, log-rank test). Multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazard method adjusted for age, gender, tumor location, tumor histology, and tumor stage showed that the CIMP status did not affect the recurrence-free survival (p=0.30; HR, 1.65; 95% CI, 0.65 to 4.21).

DISCUSSION

The CIMP concept was introduced to described a subset of colorectal cancers with a high frequency of methylation of the cancer-related CpG island foci.4 Many studies have been carried out to identify the clinicopathological and molecular features of colorectal cancer according to the CIMP status. CIMP-high colorectal cancers are associated with older age, cigarette smoking, proximal tumor location, female gender, poor differentiated histology, MSI, and BRAF mutation.5,7–13 Previous studies reported that the prognosis and response to chemotherapy of colorectal cancer patients was affected by CIMP status.24–27 However, the effect of the CIMP status on the survival outcome is still controversial owing to different marker panel and different variable inclusions of patient. In addition, a few studies were available in Korea.14,28 Therefore, this study examined the survival outcome and recurrence-free survival according to the CIMP status and MSI status in Korean cohort patients. The results showed that regardless of the MSI status, CIMP-high cancer was associated with a poor survival outcome, and colon cancer with CIMP-high/MSS in subgroup analysis showed a poor survival outcome compared to CIMP-low and negative/MSS colon cancers. However, the disease-free survival was similar in CIMP-high and CIMP-low/negative colon cancers. The discrepancy between impacts of CIMP on recurrence-free survival and that on cancer-specific survival could be caused by small sample size.

The proportion of colon cancer with CIMP-high was 17.9% in this study. This result is consistent with other studies, which reported that the prevalence of colorectal cancer with CIMP-high ranged from 12% to 29.6%.6,10,11 However, the high MSI (MSI-H) incidence in this study was 9% of all patients with colon cancer. In particular, the MSI-H incidence was 7% of all CIMP-high colon cancers. This reveals a lower incidence of MSI-H colon cancers than other studies. In a Korean study, the MSI incidence in sporadic colorectal cancers was lower than a Western population.29,30 Nevertheless, the low MSI incidence was a weak point of this study, and might be due to the small sample size and only one panel test for MSI in some cases. The small sample size was caused by the exclusion of many rectal cancer patients (46%) in previous cohort patients. The reason was why the neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy could change the tumor characteristics. Although small sample size is the major limitation in this study, we tried to reduce the selection bias to use the sample in previous cohort population only. Next, the BAT26 panel test for the MSI status was the second best in cases without matched normal tissue when an experiment on the MSI was attempted.

Although the survival outcome of each group was not compared (CIMP-high/MSI, CIMP-high/MSS, CIMP-low and negative/MSI, and CIMP-low and negative/MSS) due to the low incidence of CIMP-high/MSI-H tumors, subgroup analysis of MSS tumors revealed CIMP-high tumors to be associated with a poor outcome compared to CIMP-low/negative tumors, which is consistent with the poor outcome of CIMP-high tumors with MSS.6,15,16 Recently, the poor prognostic outcome of CIMP-high colorectal cancers with MSS was closely associated with a BRAF mutation.14,15 Although the BRAF mutation was not examined in this study, a previous study showed that more than 90% colon cancers with the BRAF mutation were CIMP-high.6 Therefore, it might not affect the main findings of the study.

Despite several limitations mentioned above, the advantage of this study had less selection bias. In addition, a few studies of the survival outcome of CIMP-high cancers have been carried out in Asian countries. These findings can assist in an analysis of the survival outcome in colon cancer with CIMP-high.

In conclusion, this study analyzed the 154 colon cancers for the CIMP and MSI status in a cohort population as well as the prognosis of colon cancer according to the CIMP status and MSI status. The CIMP-high cancers regardless of the MSI status showed a poor outcome. In subgroup analysis, the CIMP-high/MSS cancers had a poor outcome compared to CIMP-low and negative/MSS cancers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the IN-SUNG Foundation for Medical Research (CA98281) and Samsung Biomedical Research Institute (#SBRI CB02162).

Footnotes

See editorial on page 139.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM. Molecular origins of cancer: molecular basis of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2449–2460. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim YS, Deng G. Epigenetic changes (aberrant DNA methylation) in colorectal neoplasia. Gut Liver. 2007;1:1–11. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2007.1.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Issa JP. CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8681–8686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Issa JP. CpG island methylator phenotype in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:988–993. doi: 10.1038/nrc1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samowitz WS, Sweeney C, Herrick J, et al. Poor survival associated with the BRAF V600E mutation in microsatellite-stable colon cancers. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6063–6069. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weisenberger DJ, Siegmund KD, Campan M, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2006;38:787–793. doi: 10.1038/ng1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jass JR. Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology. 2007;50:113–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rashid A, Issa JP. CpG island methylation in gastroenterologic neoplasia: a maturing field. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1578–1588. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawkins N, Norrie M, Cheong K, et al. CpG island methylation in sporadic colorectal cancers and its relationship to microsatellite instability. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1376–1387. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Rijnsoever M, Grieu F, Elsaleh H, Joseph D, Iacopetta B. Characterisation of colorectal cancers showing hypermethylation at multiple CpG islands. Gut. 2002;51:797–802. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samowitz WS, Albertsen H, Herrick J, et al. Evaluation of a large, population-based sample supports a CpG island methylator phenotype in colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:837–845. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Issa JP, Shen L, Toyota M. CIMP, at last. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1121–1124. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JH, Shin SH, Kwon HJ, Cho NY, Kang GH. Prognostic implications of CpG island hypermethylator phenotype in colorectal cancers. Virchows Arch. 2009;455:485–494. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0857-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S, Cho NY, Choi M, Yoo EJ, Kim JH, Kang GH. Clinicopathological features of CpG island methylator phenotype-positive colorectal cancer and its adverse prognosis in relation to KRAS/BRAF mutation. Pathol Int. 2008;58:104–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2007.02197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahlin AM, Palmqvist R, Henriksson ML, et al. The role of the CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer prognosis depends on microsatellite instability screening status. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1845–1855. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogino S, Nosho K, Kirkner GJ, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype, microsatellite instability, BRAF mutation and clinical outcome in colon cancer. Gut. 2009;58:90–96. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.155473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oh SW, Kim YH, Choi YS, et al. The comparison of the risk factors and clinical manifestations of proximal and distal colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:56–61. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. AJCC cancer staging manual. 6th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Brahmandam M, et al. Precision and performance characteristics of bisulfite conversion and real-time PCR (MethyLight) for quantitative DNA methylation analysis. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:209–217. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.050135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boland CR, Thibodeau SN, Hamilton SR, et al. A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Microsatellite Instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5248–5257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loukola A, Eklin K, Laiho P, et al. Microsatellite marker analysis in screening for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) Cancer Res. 2001;61:4545–4549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoang JM, Cottu PH, Thuille B, Salmon RJ, Thomas G, Hamelin R. BAT-26, an indicator of the replication error phenotype in colorectal cancers and cell lines. Cancer Res. 1997;57:300–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Issa JP. Methylation and prognosis: of molecular clocks and hypermethylator phenotypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2879–2881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Rijnsoever M, Elsaleh H, Joseph D, McCaul K, Iacopetta B. CpG island methylator phenotype is an independent predictor of survival benefit from 5-fluorouracil in stage III colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2898–2903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogino S, Meyerhardt JA, Kawasaki T, et al. CpG island methylation, response to combination chemotherapy, and patient survival in advanced microsatellite stable colorectal carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2007;450:529–537. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0398-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen L, Catalano PJ, Benson AB, 3rd, O’Dwyer P, Hamilton SR, Issa JP. Association between DNA methylation and shortened survival in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with 5-fluorouracil based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6093–6098. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bae JM, Kim JH, Cho NY, Kim TY, Kang GH. Prognostic implication of the CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancers depends on tumour location. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1004–1012. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oh SY, Lee JM, Lee HW, et al. Clinicopathological significance of microsatellite instability in sporadic colorectal cancer. J Korean Surg Soc. 2006;71:420–425. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang KJ, Sinn DH, Park SH, et al. Adenoma incidence after resection of sporadic colorectal cancer with microsatellite instability. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:577–581. doi: 10.1002/jso.21548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]