Abstract

Toxic megacolon is a rare clinical complication of fulminant Clostridium difficile infection. The mortality rate of fulminant C. difficile infection is reported to be as high as 50%. Fecal microbiota transplantation is a highly effective treatment in patients with recurrent or refractory C. difficile infection. However, there are few published articles on the use of such transplantation for fulminant C. difficile infection. Here, we report on a patient with toxic megacolon complicated by C. difficile infection who was treated successfully with fecal microbiota transplantation.

Keywords: Fulminant Clostridium difficile infection, Megacolon, toxic, Fecal microbiota transplantation

INTRODUCTION

The incidence and severity of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) have been increasing recently,1 mainly because of an increase in the number of infections by the hypervirulent strain B1/NAP/027.2 Toxic megacolon is a clinical manifestation of fulminant CDI. The mortality rate of fulminant CDI is reported to be as high as 50%.3,4

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is an effective treatment option for recurrent, refractory CDI. Several studies have reported that the therapeutic efficacy of FMT for the treatment of refractory CDI is >90%. The patient’s severe medical condition makes it difficult to perform FMT in patients with fulminant CDI. Here, we report on a patient with toxic megacolon complicated by CDI who was treated successfully with FMT.

CASE REPORT

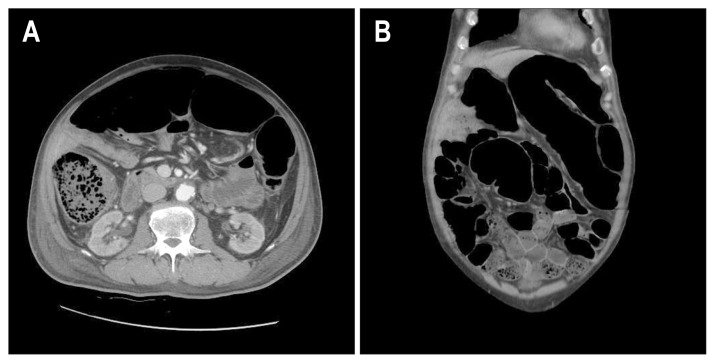

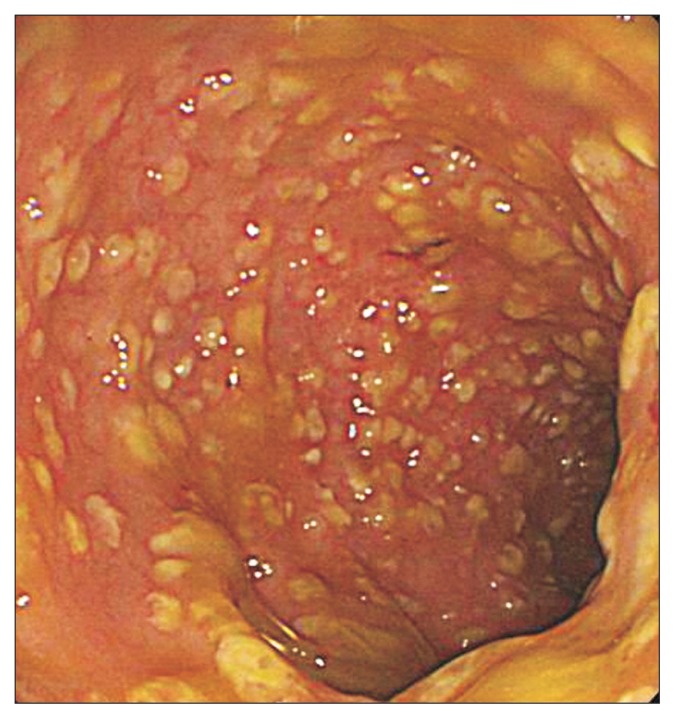

A 74-year-old man with diabetes, coronary artery disease, and thyroid cancer was transferred from another hospital to our hospital. His initial vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 100/65 mm Hg with dopamine 17 μg/hr; pulse rate, 100/min; and body temperature, 37.0°C. The initial laboratory findings were as follows: hemoglobin, 8.9 g/dL; platelets, 40–109/L; white blood cell count, 5,200/mm3; C-reactive protein, 12.67 mg/dL; albumin, 2.0 g/dL; creatinine, 2.57 mg/dL; and prothrombin time, 49% (international normalized ratio, 1.45). Chest X-ray showed bilateral infiltration of the lungs (Fig. 1). Arterial blood gas analysis on 5 L of O2 supplied by a mask was as follows: pH, 7.35; PaCO2, 31.0 mm Hg; PaO2, 72.4 mm Hg; HCO3,15.5 mEq/L; and SaO2, 92%. The patient was drowsy, and his abdomen was severely distended. Supine abdominal X-ray showed marked dilation of the colon. Abdominal computed tomography showed dilation of the entire colon by up to 7 cm in diameter in the transverse colon (Fig. 2). Urine output was 800 cc/day and 1,200 cc/day of gastric juice was drained through a nasogastric tube. The frequency of diarrhea was 10 times/day. Stool culture (chromID C. difficile; bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) and toxin assay by enzyme immunoassay (Wampole Tox A/B Quik Chek; Alere, Orlando, FL, USA) was conducted. A test for C. difficile toxins A and B was positive in stool samples but binary toxin was not detected. Sigmoidoscopy showed multiple yellowish plaques in the rectum and sigmoid colon (Fig. 3). The patient’s clinical manifestation was compatible with fulminant CDI.

Fig. 1.

Chest X-ray showing bilateral infiltration of lung.

Fig. 2.

Abdominal computed tomography showing marked dilatation of the large bowel (up to 7 cm). (A) Transverse plane. (B) Coronal plane.

Fig. 3.

Sigmoidoscopy showing multiple yellowish plaques in the sigmoid colon.

The patient had received treatment for fulminant CDI and pneumonia at the previous hospital. Despite 10 days of intravenous metronidazole (500 mg×3 times/day) and oral vancomycin (125 mg×4 times/day) at the previous hospital, the patient’s medical condition continued to worsen, and we decided that medical therapy for CDI was ineffective. We considered other treatment options. Surgical treatment was not considered because of the patient’s bleeding tendency and comorbidities of coronary artery disease and pneumonia. We decided to try FMT, which was conducted on hospital day 2. The stool source was from a nonfamily healthy donor whose stool and blood sample was already screened within 2 months of the procedure. Hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C virus antibody, C. difficile toxin, and human immunodeficiency virus were not detected. Serologic test for syphilis was negative. The donor had not used antibiotics within the past year and had no history of chemotherapy. Donor stool was collected on the day of the FMT. Fifty grams of stool and saline 150 mL (1:3) was placed into a blender (NJM-9060; NUC Electronics, Daegu, Korea). Stool and saline was ground for 3 minutes in the blender. The suspension was passed through a stainless steel tea strainer to remove large particles. The suspension was aspirated into 50 cc syringe. Because of the patient’s severe ileus, FMT was performed using colonoscopy. To minimize air inflation, colonoscopy was performed using CO2 gas supplied by a CO2 generator (EndoCO2 Pro-500; Mirae Medics, Seongnam, Korea). We inserted the colonoscope into the distal transverse colon. The prepared fecal suspension was transferred to the patient’s bowel through the biopsy channel of the colonoscope. The procedure time was about 20 minutes.

One day after FMT, abdominal distension had improved slightly, and dopamine could be tapered. The frequency of diarrhea improved to 5 times/day. Three days after the first FMT, a second FMT was tried through colonoscopy on hospital day 5. One hundred grams of stool and saline 300 mL was infused into the distal descending colon through a colonoscope. Pseudo-membranous colitis was noted to have improved mildly during the colonoscopy. After the second FMT, the frequency of diarrhea improved to 2 times/day, but was not resolved. Because we could not insert the colonoscope into the cecum, we decided that the FMT was incomplete. The patient was still drowsy. He did not appear to be able to retain the fecal suspension, although the ileus had improved.

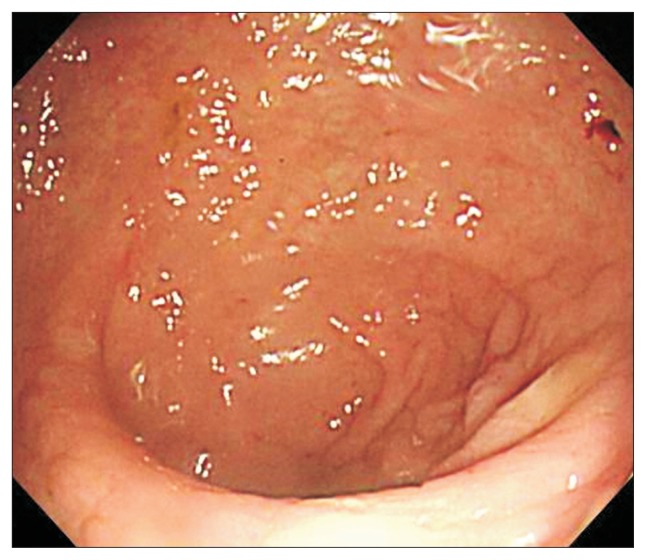

A third FMT was performed through gastroduodenoscopy 5 days after the second FMT on hospital day 10. Using gastroduodenoscopy, 80 g of stool and saline 240 mL was infused into the second portion of the duodenum. We stopped intravenous metronidazole and oral vancomycin 1 day after the third FMT. Diarrhea resolved 5 days after the third FMT on hospital day 15. Follow-up colonoscopy 1 day after the resolution of diarrhea on hospital day 16 showed normal mucosa in the sigmoid colon (Fig. 4) and that the abdominal distension had resolved fully. Supine abdominal X-ray showed a normal colonic gas pattern. The day after resolution of diarrhea, the patient started eating. Antibiotics for pneumonia were stopped on hospital day 20. The patient left the hospital on hospital day 29.

Fig. 4.

Follow-up colonoscopy showing normal mucosa in the sigmoid colon.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of fulminant CDI is up to 3% of total CDI.5 The clinical manifestations of fulminant CDI are shock and severe ileus with or without diarrhea. Fulminant CDI can be complicated by perforation.6,7 The initial treatment is the combination of oral vancomycin and intravenous metronidazole.7 Colectomy is recommended in cases of organ failure, shock, or no improvement of the clinical condition within 24 to 72 hours despite medical therapy.6 Intravenous immunoglobulin is an adjuvant treatment option, but its clinical effect is inconclusive.8,9

The patient’s medical condition worsened despite conventional treatment. We considered the option of surgery and consulted a surgeon. However, because of the patient’s coagulopathy and comorbidities, his surgical risk was considered to be very high. FMT is a highly effective treatment option for the treatment of recurrent or refractory CDI. The cure rate for FMT for refractory or recurrent CDI is >90%,10,11 and its effects are rapid. Before FMT, we asked the patient’s family about stool source. There was no family member suitable for donation. They wanted to try FMT with nonfamily donor’s stool. We tried to conduct FMT as soon as possible. In our center, we already performed several cases of FMT with nonfamily healthy donor’s stool. The donor’s stool and blood sample was screened within 2 months of the procedure. We could save time for screening of donor’s stool. FMT was performed 3 times. One day after the first FMT, we tapered dopamine and the systolic blood pressure was maintained at >100 mm Hg without the use of vasopressors. Abdominal distension had improved slightly, and the frequency of diarrhea had decreased from 10 times/day to 5 times/day, indicating the rapidity of the effectiveness of FMT. Because the patient was drowsy after the first FMT, he could not retain the infused fecal suspension and it was passed out within 30 minutes, which was insufficient for retention. We tried a second FMT using colonoscopy because the ileus had not resolved. Because the colonoscopy was performed without bowel preparation, we could not insert the colonoscope into the cecum, and we thought that the FMT was incomplete. After the second FMT, the ileus recovered partially, and we tried a third FMT using duodenal infusion. The advantage of duodenal infusion is the longer retention time in the large bowel regardless of the patient’s state of consciousness. Diarrhea resolved 5 days after the third FMT.

The first FMT was unsuccessful in this patient, and he required sequential treatment by repetition of the FMT. We believe that the first two FMTs were incomplete because of the failure of cecal intubation and insufficient retention time, and hyperproduction of toxin caused by the severe CDI.12

FMT may be another treatment option for fulminant CDI. However, it is difficult to perform colonoscopy in patients with fulminant CDI. The position of the patient during colonoscopy can aggravate shock, and the risk of bowel perforation is higher than in the normal bowel. To minimize the risk of procedure-related complications, the procedure must be conducted as quickly as possible. Repeated FMT should be considered in cases of incomplete FMT. The oral route of FMT is recommended in patients who cannot retain the fecal suspension.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Freeman J, Bauer MP, Baines SD, et al. The changing epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:529–549. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00082-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Connor JR, Johnson S, Gerding DN. Clostridium difficile infection caused by the epidemic BI/NAP1/027 strain. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1913–1924. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamontagne F, Labbé AC, Haeck O, et al. Impact of emergency colectomy on survival of patients with fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis during an epidemic caused by a hypervirulent strain. Ann Surg. 2007;245:267–272. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000236628.79550.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sailhamer EA, Carson K, Chang Y, et al. Fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis: patterns of care and predictors of mortality. Arch Surg. 2009;144:433–439. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dallal RM, Harbrecht BG, Boujoukas AJ, et al. Fulminant Clostridium difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complications. Ann Surg. 2002;235:363–372. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaber MR, Olafsson S, Fung WL, Reeves ME. Clinical review of the management of fulminant clostridium difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:3195–3203. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA) Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:431–455. doi: 10.1086/651706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McPherson S, Rees CJ, Ellis R, Soo S, Panter SJ. Intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of severe, refractory, and recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhea. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:640–645. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0511-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abougergi MS, Kwon JH. Intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of Clostridium difficile infection: a review. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:19–26. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton MJ, Weingarden AR, Sadowsky MJ, Khoruts A. Standardized frozen preparation for transplantation of fecal microbiota for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:761–767. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandt LJ, Aroniadis OC, Mellow M, et al. Long-term follow-up of colonoscopic fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1079–1087. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warny M, Pepin J, Fang A, et al. Toxin production by an emerging strain of Clostridium difficile associated with outbreaks of severe disease in North America and Europe. Lancet. 2005;366:1079–1084. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67420-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]