Abstract

AIM: To compare characteristics and outcomes of resected and nonresected main-duct and mixed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas (IPMN).

METHODS: Over a 14-year period, 50 patients who did not undergo surgery for resectable main-duct or mixed IPMN, for reasons of precluding comorbidities, age and/or refusal, were compared with 74 patients who underwent resection to assess differences in rates of survival, recurrence/occurrence of malignancy, and prognostic factors. All study participants had dilatation of the main pancreatic duct by ≥ 5 mm, with or without dilatation of the branch ducts. Some of the nonsurgical patients showed evidence of mucus upon perendoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or endoscopic ultrasound and/or after fine needle aspiration. For the surgical patients, pathologic analysis of resected specimens confirmed a diagnosis of IPMN with involvement of the main pancreatic duct or of both branch ducts as well as the main pancreatic duct. Clinical and biologic follow-ups were conducted for all patients at least annually, through hospitalization or consultation every six months during the first year of follow-up, together with abdominal imaging analysis (magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography or computed tomography) and, if necessary, endoscopic ultrasound with or without fine needle aspiration.

RESULTS: The overall five-year survival rate of patients who underwent resection was significantly greater than that for the nonsurgical patients (74% vs 58%; P = 0.019). The parameters of age (< 70 years) and absence of a nodule were associated with better survival (P < 0.05); however, the parameters of main pancreatic duct diameter > 10 mm, branch duct diameter > 30 mm, or presence of extra pancreatic cancers did not significantly influence the prognosis. In the nonsurgical patients, pancreatic malignancy occurred in 36% of cases within a mean time of 33 mo (median: 29 mo; range: 8-141 mo). Comparison of the nonsurgical patients who experienced disease progression with those who did not progress showed no significant differences in age, sex, symptoms, subtype of IPMN, or follow-up period; only the size of the main pancreatic duct was significantly different between these two sub-groups, with the nonsurgical patients who experienced progression showing a greater diameter at the time of diagnosis (> 10 mm).

CONCLUSION: Patients unfit for surgery have a 36% greater risk of developing pancreatic malignancy of the main-duct or mixed IPMN within a median of 2.5 years.

Keywords: Main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, Pancreatic surgery, Prognosis, Natural history, Risk of malignancy

Core tip: Recent studies have suggested that main-duct and mixed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) of the pancreas can be managed conservatively. We compared two groups of patients with resectable main-duct or mixed IPMN who had or had not undergone surgery. Significantly more patients who underwent the resection procedure survived, compared to the nonsurgical patients. Main-duct or mixed IPMN, when surgery is not possible, is associated with a 36% greater risk of developing pancreatic malignancy within a median time of 2.5 years. Dilatation of the main pancreatic duct is predictive of progression of malignancy.

INTRODUCTION

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia (IPMN) of the pancreas is characterized by adenomatous proliferation of the pancreatic-duct epithelium and may involve the main pancreatic duct (MPD), the branch ducts, or both[1,2]. IPMN cases are classified into the following three types, according to the structure from which they are derived: MPD, branch duct, and mixed[3]. Without exception, however, all IPMN cases are considered to be potentially malignant[4,5].

Taking into consideration the probability that IPMN will become malignant, surgical resection of the pancreatic lesion(s) is recommended to prevent the malignant transformation. Most cases of branch-duct IPMNs are benign, with the reported malignancy rates ranging from 18% to 25% and an estimated risk of invasive carcinoma of 15%[6-10]. Conversely, MPD and mixed IPMN cases are frequently malignant, with the reported rates of carcinoma being between 60% and 70% and an estimated risk of invasive carcinoma of 50%[11-14].

MPD IPMN requires surgical resection, especially when a preoperative sign of a high risk for malignancy is present, such as dilatation of the MPD (> 10 mm)[3,13,14] and/or mural nodules [detected by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)][13-15], or any other findings suggestive of malignancy [detected in fine-needle aspirates (FNA)][3]. However, in the absence of such signs, a short-term follow-up is indicated, usually involving magnetic-resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or EUS every three to six months[3]. Unfortunately, the signs/factors predictive of malignancy in MPD or mixed IPMN have not been well defined to date, and remain a subject of controversy, despite the publication of a recent consensus in 2012[3]. Recent studies have suggested that the MPD or mixed IPMN cases with lower likelihood of malignancy (i.e., MPD < 10-15 mm, no mural nodules, and negative cytology) may be managed conservatively because of the low level progression, which can last several years[16-18].

Surgical resection of MPD IPMN is the most frequently recommended treatment, but the benefit-risk ratio should be considered before applying it to any patient. The surgical intervention may include major pancreatic resection, such as the Whipple procedure, or total pancreatectomy, as in cases of multifocal lesions. However, these procedures carry their own risks of mortality and morbidity, with the respective estimates being 0%-5% and 30%-50%[19]. In addition, the following two aggravating factors should be considered in patients with IPMN as they are conditions for developing a pancreatic fistula after resection: (1) the age at diagnosis (the mean age for diagnosis of IPMN is 66 years[19,20], which suggests that the risk of possible comorbidities may increase surgical risks and thus may represent a contraindication for resection); and (2) the quality of the adjacent pancreatic parenchyma and MPD, which are often normal[19].

In the present study, we performed a comparative analysis of all patients with MPD or mixed IPMN who had undergone surgical resection and who were unfit for surgery (according to precluding conditions and patient refusal). The patients’ characteristics, outcomes, and prognostic factors were assessed for relation to the surgical resection treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and inclusion criteria

A total of 124 successive patients with MPD or mixed IPMN eligible for pancreatic surgery (i.e., a resectable IPMN at imaging) were admitted into our tertiary care center between January 1998 and November 2012. Among these patients, 50 did not undergo surgery, with 10 refusing the procedure and 40 displaying contraindications related to age and/or comorbidities; these 50 patients were included in a nonsurgical group and used for comparison with the remaining 74 patients who underwent surgery (and resection) and comprised the surgical group. Any patient who was found to have a nonresectable invasive malignant IPMN caused by a locally advanced and/or metastatic disease (as detected in cross-sectional imaging and EUS, including evidence of invasion of extra-pancreatic structures, ascites or peritoneal carcinomatosis, or distant metastasis) was excluded from the analysis.

All included patients had dilatation of the MPD ≥ 5 mm, with or without dilatation of the branch ducts and without evidence of tissular obstruction of the MPD. In addition, some of the nonsurgical patients showed evidence of mucus by a perendoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or EUS and/or after FNA. In the surgical patients, pathologic analysis of the resected specimens confirmed a diagnosis of IPMN with involvement of the MPD or of both the branch ducts as well as the MPD.

Decisions on the management of all patients were made systematically during multidisciplinary meetings that were attended by surgeons, gastroenterologists, a pathologist, and a radiologist. The possibility of surgery was evaluated according to the patient’s symptoms, the localization and extension of the IPMN lesion(s), the age of the patient, the presence or absence of comorbidities, the American Society of Anesthesiologists score, and receipt of informed consent.

Data collection and imaging at study inclusion

Data were recorded retrospectively, and included patient age, sex, medical history (including other possible neoplasias), circumstances at diagnosis, symptoms related to IPMN, date of diagnosis, and biologic data (including hepatic enzyme concentrations and lipasemia). Between 1998 and 2001, all of the patients were examined by a single-phase CT examination, but after 2001 the routine was changed to performance of a helical triple-phase CT scan with the focus on the pancreas and its surrounding tissues (with each pancreatic section being effectively collimated into 3 mm sections at a pitch of 1.5).

MRCP was performed with a 1T superconducting magnetic-resonance unit (Magnetom Impact; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), using a half-Fourier single-shot turbo spin-echo sequence as described previously[10,14]. All patients received a CT scan at the time of diagnosis, and MRCP was performed on 66% of patients.

The EUS, EUS FNA biopsy, and ERCP were performed[10,14,21,22] by an experienced operator using an EUM-160, UE-160 or GF-UC140T echo-endoscope and a TJF endoscope (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany). FNA were obtained using a USN1 22G needle biopsy (Cook Medical, Limerick, Ireland). Some of the nonsurgical patients underwent a pancreatic sphincterotomy and mucus evacuation with a balloon catheter[23]. EUS was performed at the time of diagnosis for 81% of the patients, including 38 patients who also underwent FNA procedures. ERCP was performed in 30 (40%) patients.

The data recorded from the imaging evaluations included maximal diameters of the MPD and branch-duct cyst, the properties of the tissue component surrounding the MPD, mural nodules and/or tissue thickening of the MPD and/or the branch-duct cyst wall (mainly detected by EUS), localization of the branch-duct lesions, and maximal diameter of the side-branch IPMN. In addition, the following data were recorded for all surgical patients: type of resection, pathologic findings, tumor stage, postoperative complications, and mortality.

Clinical and imaging follow-up

Clinical and biologic follow-ups were conducted at least annually for all patients, through hospitalization or consultation every six months during the first year of follow-up, together with abdominal imaging (MRCP or CT, and if necessary EUS with or without FNA). The clinical data recorded were weight loss, presence of diabetes, jaundice, abdominal pain or acute pancreatitis, time between diagnosis of IPMN and a new event, death and cause of death, and time between diagnosis of IPMN and death. Criteria collected during the imaging follow-up evaluations were increase or stability of the dilatation of the MPD and/or side-branch cysts, occurrence of a tissue mural nodule (MPD and/or branch-duct cysts) or tissue component of the pancreas, and involvement of adjacent or distant organs. The overall comparative analysis study was conducted in December 2013, i.e., at 12 mo after inclusion of the last patient. Each patient provided informed written consent for study participation, in accordance with the rules of the French Society of Gastroenterology-SNFGE and Endoscopy-SFED (http://www.sfed.org/Fiches-d-Informations).

Statistical analysis

Qualitative and quantitative data were analyzed using Student’s t, χ2, or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate, with GraphPad-Instat 3.1a software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, United States). Actuarial survival analyses, according to the Kaplan-Meier model, were calculated using R software, version 2.15.0. Comparison of survival rates between the surgical and nonsurgical groups was performed using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors were carried out using the log-rank test, the Wald test, and Cox’s model. Only variables with a P < 0.2 in the univariate analysis were included in the subsequent multivariate analysis. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

General characteristics of patients

The main characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1 and stratified according to the surgical and nonsurgical grouping. The were no statistically significant differences between the two groups for sex, symptoms, morphologic criteria (MPD size, branch duct involvement, lesion localization, MPD diameter, presence of nodules and thickening of the wall of the MPD and/or side-branch cyst), rate of invasive malignancy, or the follow-up period. However, the nonsurgical patients were significantly older and had a greater rate of extra-pancreatic cancer history. Mortality was also greater in the nonsurgical group, but the difference was not statistically significant. Among the surgical patients, 52 underwent a Whipple procedure (70%), with six having undergone a total pancreatectomy, 15 having undergone a left (spleno)-pancreatectomy, and one having undergone a central pancreatectomy.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of patients n (%)

| Characteristic | Total population, n = 124 | Surgical patients, n = 74 | Nonsurgical patients, n = 50 | P value1 |

| Age at diagnosis (yr), mean ± SD (range) | 64.4 ± 9.0 (33-82) | 61.2 ± 7.0 (33-73) | 69.0 ± 8.0 (58-2) | < 0.01 |

| Sex ratio, male:female | 74:50 | 46:28 | 28:22 | 0.57 |

| Associated non-pancreatic cancers2 | 26 (22.0) | 10 (13.5) | 16 (32.0) | 0.02 |

| Symptoms | 96 (77.5) | 61 (82.5) | 35 (70.0) | 0.12 |

| Acute pancreatitis | 45 (36.0) | 32 (43.0) | 13 (36.0) | 0.06 |

| Diabetes | 15 (12.0) | 12 (16.0) | 3 (6.0) | 0.10 |

| Jaundice | 13 (10.4) | 7 (13.5) | 6 (12.0) | 0.76 |

| Others | 23 (18.5) | 10 (13.5) | 13 (26.0) | 0.10 |

| Fortuitous | 28 (22.5) | 13 (17.5) | 15 (30.0) | 0.12 |

| Localization of IPMN | ||||

| Head | 93 (75.0) | 58 (78.5) | 35 (70.0) | 0.29 |

| Body | 12 (9.5) | 6 (8.5) | 6 (12.0) | 0.54 |

| Tail | 10 (8.0) | 5 (6.5) | 5 (10.0) | 0.52 |

| Diffuse | 9 (7.5) | 5 (6.5) | 4 (8.0) | 1.00 |

| Involvement of branch duct (mixed forms) | 101 (81.5) | 59 (79.0) | 42 (84.0) | 0.64 |

| Maximal diameter of main duct at diagnosis, mm | 7.6 ± 0.4 (6) | 7.2 ± 0.4 (6) | 8.3 ± 0.9 (6) | 0.19 |

| mean ± SD (median) | ||||

| Tissue nodule or wall thickening at imaging3 | 36 (29.0) | 21 (28.0) | 15 (30.0) | 0.84 |

| Malignant invasive IPMN | 62 (50.0) | 41 (55.5) | 21 (40.0)4 | 0.19 |

| Follow-up after diagnosis (mo), median (range) | 24 (162-6) | 24 (162-9) | 30 (141-6) | 0.85 |

| Death | 41 (33.0) | 19 (26.0) | 22 (44.0) | 0.05 |

Nonsurgical vs surgical groups;

Lung: n = 5, prostate: n = 7, hemopathy: n = 3, mammary: n = 3, colon: n = 2, miscellaneous: n = 6;

Main pancreatic duct or branch-duct cyst, or both, mainly visualized by endoscopic ultrasound;

Occurrence during follow-up in 18 patients. IPMN: Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm.

Histologic criteria

Cytologic samples were taken from 25 (50%) of the nonsurgical patients, and the presence of mucus was confirmed in all cases. The cytologic analyses showed results of “not contributive” or “normal” in 11 (22%) cases, but revealed lesions of low-grade dysplasia in eight (11%) cases, lesions of high-grade dysplasia in three (6%) cases, and adenocarcinoma in three (6%) cases. For the surgical patients, IPMN with invasive adenocarcinoma occurred in 41 (55%) cases, high-grade dysplasia IPMN in 11 (15%) cases, and intermediate or low-grade dysplasia IPMN in 22 (30%) cases. The resection margins were considered incomplete (R1) in four patients; all other cases were considered as complete R0 resections (94.5%).

Follow-up of nonsurgical patients

Eighteen (36%) patients developed degenerative invasive IPMN during the follow-up period; the median time to progression was 29 mo (range: 8-141 mo) after the initial diagnosis. Patients who developed degenerative IPMN frequently (89%) had a major change in their clinical status [i.e., the appearance of jaundice, carcinomatous ascites, a painful disease, or bowel obstruction (Table 2)], though two patients had no symptoms. Imaging features for these conditions were pancreatic-tissue infiltration with or without peritoneal carcinomatosis (n = 6), involvement of the common bile duct (n = 10), and/or hepatic metastasis (n = 2). Eight (44%) patients showed an increase in MPD size during the follow-up. Carcinomatous transformation was proven in 16 cases upon a new EUS-guided FNA biopsy of a tissular mass, a pancreatic-juice sample during ERCP, or a biopsy during laparotomy. Of the 21 patients with degenerative IPMN (shown by three patients at the time of diagnosis and 18 during the follow-up period), five received palliative chemotherapy and one underwent a subsequent R1 resection. The other nonsurgical patients did not receive any other treatments (except surgical bypass or biliary stenting) because of their poor general condition (World Health Organization score ≥ 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of nonsurgical patients with progression of malignancy in the main duct or mixed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas

| Age, yr | Sex | Localization |

At diagnosis |

Clinical outcome | Time until progression, mo | |

| Symptoms | Size of the main duct, mm | |||||

| 72 | F | Head | Acute pancreatitis | 10 | Jaundice | 141 |

| 76 | F | Head | Pain | 7 | Jaundice | 129 |

| 73 | M | Head | Acute pancreatitis | 14 | Ascites | 61 |

| 71 | M | Diffuse | Acute pancreatitis | 10 | None | 59 |

| 80 | F | Head | Fortuitous | 6 | Jaundice | 65 |

| 72 | M | Diffuse | Fortuitous | 60 | Occlusion | 49 |

| 78 | M | Body | Pain, weight loss | 5.5 | Ascites | 40 |

| 69 | M | Head | Fortuitous | 7 | Jaundice | 39 |

| 71 | F | Head | Weight loss | 6 | Jaundice | 30 |

| 66 | M | Body | Fortuitous | 15 | Ascites | 28 |

| 82 | F | Head | Pain, weight loss | 10 | Jaundice | 24 |

| 82 | M | Head | Fortuitous | 6 | Painful | 12 |

| 67 | F | Diffuse | Jaundice | 10 | Jaundice | 12 |

| 54 | M | Head | Pain | 17 | Jaundice | 12 |

| 67 | F | Tail | Fortuitous | 5 | None | 12 |

| 77 | M | Head | Fortuitous | 5.5 | Jaundice | 9 |

| 80 | F | Head | Weight loss | 6 | Jaundice | 8 |

| 76 | F | Body | Pain | 7 | Painful | 8 |

M: Male; F: Female.

Twenty-nine (58%) of the total nonsurgical patients did not show signs of disease progression or any new clinical or radiologic events/signs within a median follow-up time of 30 mo (range: 12-141 mo). The characteristics of the nonsurgical IPMN patients with disease progression are compared to those of the nonsurgical patients who did not progress in Table 3. These two subgroups of patients appeared similar in terms of age, sex, symptoms, subtype of IPMN and follow-up period; there was, however, a significant difference between the two subgroups for the MPD size, with the progressive disease subgroup having greater size at the time of diagnosis (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of the main characteristics of patients in the nonsurgical subgroup with and without progression of malignancy of the main duct or mixed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas n (%)

| Characteristic | Nonresected IPMN with malignant progression, n = 18 | Nonresected IPMN without malignant progression, n = 32 | P value |

| Age1 (yr), mean ± SD | 73.0 ± 7 | 68.5 ± 8.0 | 0.06 |

| Sex, male:female | 9:9 | 19:13 | 0.56 |

| With symptoms | 11 (61) | 24 (75) | 0.34 |

| Size of the MPD (mm), mean ± SE (median)1 | 11.5 ± 3.0 (7.0) | 6.9 ± 0.4 (5.7) | < 0.05 |

| Mixed form | 13 (72) | 29 (90) | 0.11 |

| Size of the BD1 (mm), mean ± SE (median)1 | 27.3 ± 4.3 (25.0) | 22.2 ± 2.6 (17.0) | 0.30 |

| Tissue nodule or wall thickening2 | 8 (44) | 7 (22) | 0.11 |

| Follow-up time after diagnosis (mo), median | 29 | 30 | 0.6 |

At diagnosis;

MPD and/or branch-duct cyst. BD: Branch duct; IPMN: Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm; MPD: Main pancreatic duct.

Follow-up of surgical patients

The postoperative course of patients who underwent surgery had a complication rate of 20%. The complications included pancreatic fistula (n = 5), gastroparesis (n = 5), anastomotic leakage (n = 3), abscess in the pancreatectomy site (n = 2), postoperative ileus (n = 1), acute pancreatitis (n = 1), infarction of the upper part of the spleen (n = 1), and severe imbalance of diabetes (n = 1). No postoperative deaths occurred. Among the 41 patients who had degenerative invasive IPMN, all five who had received an R1-margin resection were given palliative chemotherapy. For the other 37 patients, all of who received an R0 resection, 18 were given adjuvant chemotherapy. Sixteen (22%) patients, including the five R1 cases, presented with disease recurrence after a median time of 15 mo (range: 10-68 mo). The initial histologic analyses of these 16 patients showed degenerative invasive IPMN in 15 cases (N1 status in seven cases), and high-grade dysplasia in one case. All these latter patients with recurrence received palliative chemotherapy. Fifty-eight (78%) of the total surgical patients showed no recurrence of their disease after a median follow-up of 26 mo (range: 12-162 mo).

Mortality, survival, and prognostic factors

The overall number of deaths in the study series was 41 (33%). In the nonsurgical group, the causes of death (n = 22, 44%) were development of invasive pancreatic carcinoma (n = 17), severe cardiac disease (n = 4), and severe acute pancreatitis after an ERCP procedure (n = 1). For the 19 (26%) surgical patients who died, the causes of death were development of invasive pancreatic carcinoma after recurrence (n = 16), severe cardiac disease (n = 1), lung carcinoma (n = 1), and gastrointestinal bleeding (n = 1).

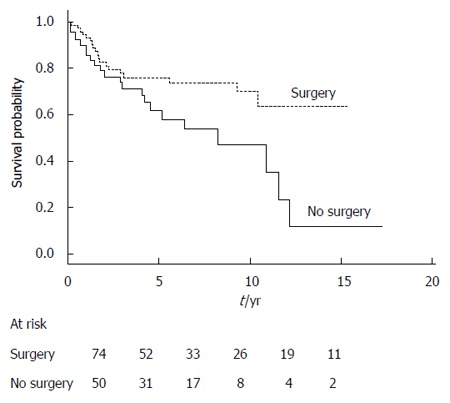

The overall survival of surgical patients was significantly superior to that of the nonsurgical patients (Table 4). This difference was also statistically significant when we considered only the disease-related deaths in both groups of patients (data not shown). Survival curves generated according to receipt of surgical resection are shown in Figure 1. Among the prognostic factors, age < 70 years and absence of a nodule or thickening of the MPD or side-branch cyst wall were significantly associated with better survival (the global log-rank score and Wald test from the multivariate analyses was 0.0016) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Analysis of prognostic factors in 124 patients with a resected or nonresected main-pancreatic duct and mixed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas

| Variable (n) |

Univariate analyses by log-rank test |

Multivariate analyses by Cox’s model |

||

| RR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Surgery | 0.02 | 0.08 | ||

| No (50) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes (74) | 0.48 (0.26-0.88) | 0.54 (0.27-1.09) | ||

| Age at diagnosis | 0.01 | 0.13 | ||

| < 70 yr (83) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 70 yr (41) | 2.36 (1.26-4.40) | 1.72 (0.86-3.46) | ||

| Extra-pancreatic cancer | 0.13 | - | ||

| No (98) | 1 | - | ||

| Yes (26) | 1.66 (0.86-3.22) | - | ||

| MPD size > 10 mm | 0.13 | - | ||

| No (100) | 1 | - | ||

| Yes (24) | 1.66 (0.86-3.22) | - | ||

| Nodule1 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| No (88) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes (36) | 2.42 (1.17-5.00) | 2.71 (1.29-5.69) | ||

| BD size > 30 mm | 0.85 | - | ||

| No (94) | 1 | - | ||

| Yes (30) | 1.08 (0.51-2.29) | - | ||

| Fortuitous | 0.63 | - | ||

| No (96) | 1 | - | ||

| Yes (28) | 1.19 (0.58-2.45) | - | ||

| Acute pancreatitis | 0.24 | - | ||

| No (79) | 1 | - | ||

| Yes (45) | 0.68 (0.35-1.30) | - | ||

Nodule and wall thickening of MPD and/or branch-duct cysts. BD: Branch duct; MPD: Main pancreatic duct.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival times depending on treatment. Nonsurgical (nonresected; solid line) and surgical (resected; dashed line) main-pancreatic duct and mixed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm patients.

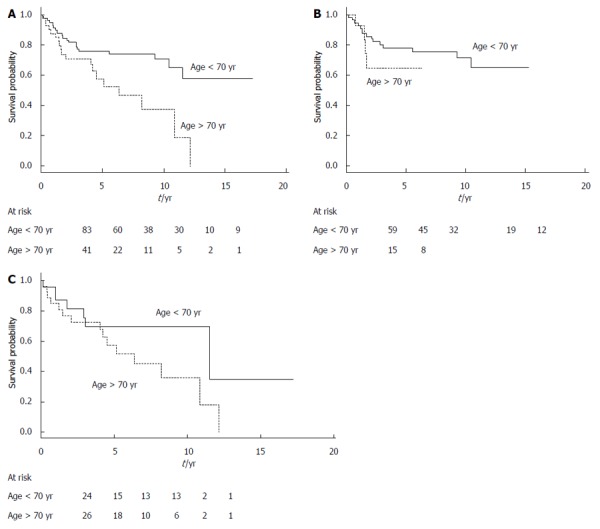

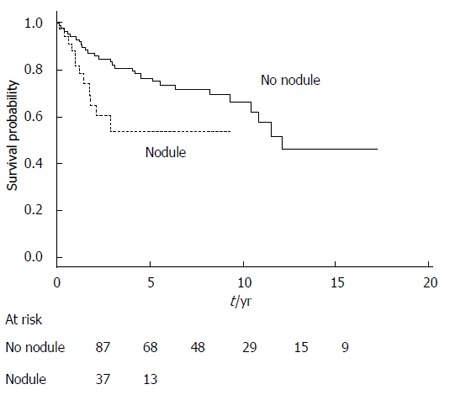

Figure 2 shows the survival curves generated according to the patients’ age for the entire study series. The survival curves are similar for the surgical and nonsurgical groups, with a cumulative probability of better survival when age was < 70 years, but the results of log-rank testing did not reach statistical significance. Figure 3 shows the survival curves depending on the presence of a mural nodule and/or thickening of MPD or side-branch cyst wall (obtained at imaging, mainly using EUS and/or CT scans and an MRI). Among other factors, main pancreatic duct size > 10 mm, branch duct size > 30 mm, presence of extra-pancreatic cancers or acute pancreatitis, and fortuitous diagnosis did not significantly influence the prognosis.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival times depending on age. A: Both nonsurgical (nonresected) and surgical (resected); B: Surgical; and C: Nonsurgical main-pancreatic duct and mixed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm patients (solid line: patients aged < 70 years; dashed line: patients aged > 70 years).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival times depending on nodules. Presence (dashed line) or absence (solid line) of tissular nodules [and/or wall thickening of main-pancreatic duct (MPD) or branch-duct cysts] at diagnosis in both nonsurgical (nonresected) and surgical (resected) MPD and mixed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm patients.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we compared the clinical outcomes of patients with resectable MPD or mixed IPMN who had or had not undergone surgical resection. Our results confirmed the importance of surgery to treat this subtype of IPMN. The alternative wait-and-watch attitude seems to be a highly questionable approach for some patients. More than one-third of our nonsurgical patients developed invasive pancreatic carcinoma within three years, and mortality among these patients was mainly caused by carcinomatous progression of the IPMN.

In our study, 50 patients were followed who had resectable MPD IPMN, but whose comorbidities, older age, antecedents of previous carcinoma and/or patient refusal led to a conservative approach. The statistically significant differences between the patients in the surgical and nonsurgical groups were age, previous history of extra-pancreatic cancer, and mortality. A significant increase in extra-pancreatic cancer has already been reported in the literature[24-26]. In most cases, a diagnosis of extra-pancreatic cancer preceded that of IPMN. The relationship between IPMN and extra-pancreatic cancer remains controversial and, at the present time, it is not considered during routine screening of this population[3].

In the nonsurgical group, most cases of pancreatic carcinoma were diagnosed through the presentation of clinical symptoms, with concomitant radiologic signs of malignancy. We made a subgroup comparison of the nonsurgical patients whose disease had progressed toward invasive carcinoma and those whose disease did not progress, with each subgroup having the same follow-up period. The only clinical or anatomic characteristic examined that was found to be a predictive factor for progression was the initial size of the MPD. Indeed, in the subgroup of nonsurgical patients whose disease progressed to degenerative IPMN, the mean size of the MPD was > 10 mm, as previously reported[16,18].

We also performed an investigation to individualize the prognostic factors among the entire study series. Surgical resection, age, and the presence of a nodule were found to significantly influence the prognosis after univariate analysis.

Age (> 70 years) was significantly associated with a worse prognosis. This finding may reflect the fact that the patients in the nonsurgical group were significantly older than those in the surgical group, but may also be related to the general clinical observation that malignancy is more common in older patients[27]. Recently, age has been also implicated as a contributing factor to mortality from IPMN, but as independent from the evolution of IPMN itself when other comorbidities are taken into account[28].

Among the other potential prognostic factors examined in this study, the contribution of increased branch-duct size has been reported by many others[13-15,29-34]. Yet, the results from recent works do not support its characterization as a definitive prognostic factor[12,35]. Kawakubo et al[35] demonstrated that the presence of a hypo-attenuating area (assessed by CT) significantly increased the risk for pancreatic cancer-specific mortality among IPMN patients (for both branch-duct and MPD IPMN). Moreover, the authors showed that cyst diameter, main-pancreatic duct diameter, and the presence of a mural nodule were not significantly associated specifically with mortality from pancreatic cancer[35]. The collective results in the literature to date highlight the difficulty in determining definitive criteria that can predict malignancy and prognosis.

From our current study of MPD or mixed IPMN cases, the initial size of the MPD could be considered in greater depth, as well as the presence of mural nodules (and wall thickening), the sizes of which were not defined. However, in our study, only 28% of the surgical patients had a nodule at imaging. Despite an invasive malignant IPMN having been detected on the resected specimen of most patients (data not shown), more than 50% of the invasive malignant IPMNs were free of nodules or wall thickening.

The limitations of our study include its retrospective nature and the long period of inclusion of cases. The long period of patient-inclusion may have induced a bias related to differences in imaging and morphologic-examination techniques over time. However, in our scheme of inclusion, the proportions of patients who did and did not undergo surgery were similar annually (data not shown). In addition, the retrospective collection of data and the long period of inclusion rendered it difficult to standardize some of the radiologic features, such as size and shape of the mural nodules and branch-duct cyst/MPD wall thickening.

The strengths of our study, however, are the extended follow-up period used to examine this patient population and the presence of a control group during the same period. Table 5 details the previous studies (including the present study) that have investigated and followed non-operated MPD and mixed IPMN patients[16-18,36]. The percentages of IPMN cases that progressed toward malignancy ranged from 13% to 40%, with a mean time to progression of 30 to 42 mo and dilatation of the MPD as a common predictive factor for this progression.

Table 5.

Results from followed patients with non-operated main-duct or mixed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas

| Ref. | Patients, n | Malignant progression | Time to progression in month, mean (range) | Predictors of malignant progression |

| Uehara et al[17], 2010 | 20 | 40% | (20-35) | None1 |

| Takuma et al[18], 2011 | 20 | 20% | 32 (17-65) | Dilatation of the MPD > 10 mm |

| Ogura et al[16], 2013 | 20 | 40% | 30 (18-46) | Dilatation of the MPD > 15 mm; diffuse lesions |

| Roch et al[36], 2014 | 70 | 13% | 42 (12-108) | Diffuse dilatation of the MPD2 |

| Present study | 50 | 36% | 33 (8-141) | Dilatation of the MPD > 10 mm |

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with lower likelihood of malignancy at baseline;

Also included an increase in serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and alkaline phosphatase levels, absence of extra pancreatic cyst. MPD: Main pancreatic duct.

In conclusion, this study confirms that the best treatment for mixed IPMN or MPD IPMN, which are risk factors for malignancy, is surgical resection, as this approach offers a 74% survival rate at five years. In resectable MPD and mixed IPMN, and when factors that prevent resection are not present, a watch-and-wait attitude is not appropriate; surgical pancreatic resection is warranted. If a close follow-up is discussed, or in cases where there is patient refusal, we found that malignancy progression occurred in 36% of these patients within a median time < 2.5 years, with survival at five years being only 58%. Except for the size of the MPD at diagnosis (> 10 mm in diameter), no specific factor was found that could strongly predict progression of malignancy. Thus, it is difficult to isolate a subgroup that could be conservatively managed. Therefore, if there is no contraindication (caused by comorbidities and/or age), surgery should be systematically discussed.

COMMENTS

Background

Without exception, all intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas (IPMN) cases are considered to be potentially malignant. In most cases, however, branch-duct IPMNs are benign, with malignancy rates reported between 18% and 25% and having a 15% risk of invasive carcinoma. Conversely, main-pancreatic duct and mixed IPMN cases are frequently malignant, with their reported rates of carcinoma reaching 60%-70%, and having a 50% risk of invasive carcinoma.

Research frontiers

Main-pancreatic duct IPMN requires surgical resection, especially when the preoperative signs of a high risk for malignancy are present, including dilatation of the main pancreatic duct by > 10 mm, mural nodules (detected by endoscopic ultrasound), or suspicion of malignancy (detected in fine-needle aspirates). Recent studies have suggested that main-pancreatic duct or mixed IPMN, with a lower likelihood of malignancy, could be managed conservatively because of the low rate of progression, which can last over several years.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In resectable main-pancreatic duct and mixed IPMN, and in the absence of factors that prevent resection, if a close follow-up is discussed or in cases where there is patient refusal, we found that malignancy progression occurred in 36% of these patients within a median time < 2.5 years and with a survival rate at five years of only 58%.

Applications

Except for the size of the main pancreatic duct (>10 mm in diameter), no specific factor could strongly predict progression of malignancy in non-operated main-duct IPMN. Consequently, it is difficult to isolate a subgroup of patients who are amenable to surgery that could be conservatively managed. In these conditions, if there is no contraindication (caused by comorbidities and/or age), surgery should be systematically discussed.

Terminology

IPMN of the pancreas is characterized by adenomatous proliferation of the pancreatic duct epithelium and may involve the main pancreatic duct, the branch ducts, or both (mixed form).

Peer-review

In this study, the clinicopathologic characteristics and outcomes of resected and nonresected main-duct and mixed IPMN of the pancreas have been investigated. This is a good paper for clinicians working in this field in terms of its novel insights into the clinical properties and therapeutic approach.

Footnotes

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: September 4, 2014

First decision: September 27, 2014

Article in press: December 8, 2014

P- Reviewer: Elpek GO, Paydas S S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Hruban RH, Takaori K, Klimstra DS, Adsay NV, Albores-Saavedra J, Biankin AV, Biankin SA, Compton C, Fukushima N, Furukawa T, et al. An illustrated consensus on the classification of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:977–987. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000126675.59108.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka M, Chari S, Adsay V, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Falconi M, Shimizu M, Yamaguchi K, Yamao K, Matsuno S. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2006;6:17–32. doi: 10.1159/000090023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka M, Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay V, Chari S, Falconi M, Jang JY, Kimura W, Levy P, Pitman MB, Schmidt CM, Shimizu M, Wolfgang CL, Yamaguchi K, Yamao K; International Association of Pancreatology. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt CM, White PB, Waters JA, Yiannoutsos CT, Cummings OW, Baker M, Howard TJ, Zyromski NJ, Nakeeb A, DeWitt JM, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: predictors of malignant and invasive pathology. Ann Surg. 2007;246:644–651; discussion 651-654. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318155a9e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagai K, Doi R, Kida A, Kami K, Kawaguchi Y, Ito T, Sakurai T, Uemoto S. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: clinicopathologic characteristics and long-term follow-up after resection. World J Surg. 2008;32:271–278; discussion 279-280. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadakari Y, Ienaga J, Kobayashi K, Miyasaka Y, Takahata S, Nakamura M, Mizumoto K, Tanaka M. Cyst size indicates malignant transformation in branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas without mural nodules. Pancreas. 2010;39:232–236. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181bab60e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanno A, Satoh K, Hirota M, Hamada S, Umino J, Itoh H, Masamune A, Asakura T, Shimosegawa T. Prediction of invasive carcinoma in branch type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:952–959. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang DW, Jang JY, Lee SE, Lim CS, Lee KU, Kim SW. Clinicopathologic analysis of surgically proven intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas in SNUH: a 15-year experience at a single academic institution. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397:93–102. doi: 10.1007/s00423-010-0674-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mimura T, Masuda A, Matsumoto I, Shiomi H, Yoshida S, Sugimoto M, Sanuki T, Yoshida M, Fujita T, Kutsumi H, et al. Predictors of malignant intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:e224–e229. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181d8fb91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arlix A, Bournet B, Otal P, Canevet G, Thevenot A, Kirzin S, Carrere N, Suc B, Moreau J, Escourrou J, et al. Long-term clinical and imaging follow-up of nonoperated branch duct form of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2012;41:295–301. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182285cc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nara S, Onaya H, Hiraoka N, Shimada K, Sano T, Sakamoto Y, Esaki M, Kosuge T. Preoperative evaluation of invasive and noninvasive intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: clinical, radiological, and pathological analysis of 123 cases. Pancreas. 2009;38:8–16. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318181b90d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anand N, Sampath K, Wu BU. Cyst features and risk of malignancy in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:913–921; quiz e59-60. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugiyama M, Izumisato Y, Abe N, Masaki T, Mori T, Atomi Y. Predictive factors for malignancy in intraductal papillary-mucinous tumours of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1244–1249. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bournet B, Kirzin S, Carrère N, Portier G, Otal P, Selves J, Musso C, Suc B, Moreau J, Fourtanier G, et al. Clinical fate of branch duct and mixed forms of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia of the pancreas. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1211–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvia R, Fernández-del Castillo C, Bassi C, Thayer SP, Falconi M, Mantovani W, Pederzoli P, Warshaw AL. Main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: clinical predictors of malignancy and long-term survival following resection. Ann Surg. 2004;239:678–685; discussion 685-687. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000124386.54496.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogura T, Masuda D, Kurisu Y, Edogawa S, Imoto A, Hayashi M, Uchiyama K, Higuchi K. Potential predictors of disease progression for main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1782–1786. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uehara H, Ishikawa O, Ikezawa K, Kawada N, Inoue T, Takakura R, Takano Y, Tanaka S, Takenaka A. A natural course of main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas with lower likelihood of malignancy. Pancreas. 2010;39:653–657. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181c81b52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takuma K, Kamisawa T, Anjiki H, Egawa N, Kurata M, Honda G, Tsuruta K, Horiguchi S, Igarashi Y. Predictors of malignancy and natural history of main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2011;40:371–375. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182056a83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H, Chen T, Wang H, Song Y, Li X, Wang J. A systematic review of the Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Mortality and morbidity and its Portsmouth modification as predictors of post-operative morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing pancreatic surgery. Am J Surg. 2013;205:466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noda H, Kamiyama H, Kato T, Watanabe F, Toyama N, Konishi F. Risk factor for pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy performed by a surgeon during a learning curve: analysis of a single surgeon’s experiences of 100 consecutive patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:1990–1993. doi: 10.5754/hge11821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bournet B, Migueres I, Delacroix M, Vigouroux D, Bornet JL, Escourrou J, Buscail L. Early morbidity of endoscopic ultrasound: 13 years’ experience at a referral center. Endoscopy. 2006;38:349–354. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-921173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bournet B, Souque A, Senesse P, Assenat E, Barthet M, Lesavre N, Aubert A, O’Toole D, Hammel P, Levy P, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy coupled with KRAS mutation assay to distinguish pancreatic cancer from pseudotumoral chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2009;41:552–557. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parsi MA, Stevens T, Dumot JA, Zuccaro G. Endoscopic therapy of recurrent acute pancreatitis. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76:225–233. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76a.08017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reid-Lombardo KM, Mathis KL, Wood CM, Harmsen WS, Sarr MG. Frequency of extrapancreatic neoplasms in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: implications for management. Ann Surg. 2010;251:64–69. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b5ad1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benarroch-Gampel J, Riall TS. Extrapancreatic malignancies and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;2:363–367. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v2.i10.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baumgaertner I, Corcos O, Couvelard A, Sauvanet A, Rebours V, Vullierme MP, Hentic O, Hammel P, Lévy P, Ruszniewski P. Prevalence of extrapancreatic cancers in patients with histologically proven intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2878–2882. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bassi C, Sarr MG, Lillemoe KD, Reber HA. Natural history of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN): current evidence and implications for management. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:645–650. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0447-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawakubo K, Tada M, Isayama H, Sasahira N, Nakai Y, Takahara N, Miyabayashi K, Yamamoto K, Mizuno S, Mohri D, et al. Risk for mortality from causes other than pancreatic cancer in patients with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2013;42:687–691. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318270ea97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maire F, Hammel P, Terris B, Paye F, Scoazec JY, Cellier C, Barthet M, O’Toole D, Rufat P, Partensky C, et al. Prognosis of malignant intraductal papillary mucinous tumours of the pancreas after surgical resection. Comparison with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2002;51:717–722. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.5.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimizu Y, Yamaue H, Maguchi H, Yamao K, Hirono S, Osanai M, Hijioka S, Hosoda W, Nakamura Y, Shinohara T, et al. Predictors of malignancy in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: analysis of 310 pancreatic resection patients at multiple high-volume centers. Pancreas. 2013;42:883–888. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31827a7b84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jang JY, Kim SW, Ahn YJ, Yoon YS, Choi MG, Lee KU, Han JK, Kim WH, Lee YJ, Kim SC, et al. Multicenter analysis of clinicopathologic features of intraductal papillary mucinous tumor of the pancreas: is it possible to predict the malignancy before surgery? Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:124–132. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang SE, Shyr YM, Chen TH, Su CH, Hwang TL, Jeng KS, Chen JH, Wu CW, Lui WY. Comparison of resected and non-resected intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. World J Surg. 2005;29:1650–1657. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim JH, Eun HW, Kim KW, Lee JY, Lee JM, Han JK, Choi BI. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms with associated invasive carcinoma of the pancreas: imaging findings and diagnostic performance of MDCT for prediction of prognostic factors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:565–572. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shin SH, Han DJ, Park KT, Kim YH, Park JB, Kim SC. Validating a simple scoring system to predict malignancy and invasiveness of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. World J Surg. 2010;34:776–783. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0416-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawakubo K, Tada M, Isayama H, Sasahira N, Nakai Y, Takahara N, Uchino R, Hamada T, Miyabayashi K, Yamamoto K, et al. Disease-specific mortality among patients with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:486–491. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roch AM, Ceppa EP, Al-Haddad MA, DeWitt JM, House MG, Zyromski NJ, Nakeeb A, Schmidt CM. The natural history of main duct-involved, mixed-type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm: parameters predictive of progression. Ann Surg. 2014;260:680–688; discussion 688-690. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]