Abstract

Background/Aims

The clinical outcome of patients with a partial virological response (PVR) to entecavir (ETV), in particular nucloes(t)ide analogue (NA)-experienced patients, has not been thoroughly investigated. The aim of the present study was to assess long-term outcomes in NA-naive and NA-experienced chronic hepatitis B patients with a PVR to ETV.

Methods

Chronic hepatitis B patients treated with ETV (0.5 mg/day) for at least 1 year were enrolled retrospectively. PVR was defined as a decrease in hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA titer of more than 2 log10 IU/mL, yet with residual serum HBV DNA, as determined by real time-polymerase chain reaction, at week 48 of ETV therapy.

Results

A total of 202 patients (127 NA-naive and 75 NA-experienced, male 70.8%, antigen positive 53.2%, baseline serum HBV DNA 6.2 ± 1.5 log10 IU/mL) were analyzed. Twenty-eight patients demonstrated a PVR. The PVR was associated with a high serum HBV DNA titer at baseline and at week 24. Virological response (< 60 IU/mL) was achieved in 46.2%, 61.5%, 77.6%, and 85% of patients with PVR at week 72, 96, 144, and 192, respectively. Resistance to antivirals developed in two NA-experienced patients. Failure of virological response (VR) in patients with PVR was associated with high levels of serum HBV DNA at week 48.

Conclusions

Patients with PVR to ETV had favorable long-term virological outcomes. The low serum level of HBV DNA (< 200 IU/mL) at week 48 was associated with subsequent development of a VR in patients with PVR to ETV.

Keywords: Hepatitis B, chronic; Entecavir; Partial virological response; Nucleos(t)ide analogue-experienced

INTRODUCTION

Chronic infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major cause of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) worldwide. The natural course of chronic HBV infection is highly diverse at the individual level, ranging from inactive carriers to end-stage liver disease or HCC [1]. While many viral and host factors can affect this course, the level of serum HBV DNA is one of the most important factors affecting prognosis [2,3]. The long-term suppression of HBV replication is therefore an important goal in the effective treatment of chronic HBV infection.

Entecavir (ETV) is a potent nucloes(t)ide analogue (NA) that inhibits HBV replication [4,5]. Long-term use of ETV reduces serum HBV DNA [6], improves liver histology [7,8] and lowers the incidence of HCC [9]. However, the emergence of antiviral drug resistance can attenuate the efficacy of long-term NA use [10]. Risk factors associated with the development of such resistance include high levels of HBV DNA prior to treatment with NA, inadequate viral suppression during therapy and NA with a low genetic barrier to resistance [11,12].

A partial virological response (PVR) is defined as a decrease in HBV DNA titer of more than 2 log10 IU/mL, with residual serum HBV DNA detectable by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). For NAs with a low genetic barrier to resistance this should be determined at week 24 [12,13] and for NAs with a high genetic barrier it should be determined at week 48 [14]. PVR in response to treatment with NAs with a low genetic barrier, such as lamivudine (LAM) and telbivudine, is associated with a higher risk of resistance, in which case a change to a more potent drug or combination therapy is recommended [13,14]. The long-term prognosis of patients with PVR to ETV has not been fully defined and the optimal approach to management for such cases remains the subject of debate.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the risk factors for developing a PVR to ETV, and assess the long-term prognosis of PVR to ETV in NA-naive and NA-experienced patients.

METHODS

Patients

Patients with chronic HBV infection who were treated with ETV (0.5 mg/day) between January 2007 and September 2012 were retrospectively enrolled from at a single treatment center. Those patients whose medication adherence was reported to be over 80% and whose treatment duration was in excess of 48 weeks were analyzed in this study. Patients excluded from the study included those with malignancy (including HCC), coinfection with hepatitis C virus or human immunodeficiency virus, or had experienced antiviral drug resistance and were not indicated for ETV monotherapy. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review of Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital, Goyang, Korea.

Data collection

Patient history covering previous antiviral treatments, previous antiviral drug resistance, presence of cirrhosis and adherence to medication were collected. Hepatitis B envelop antigen (HBeAg), hepatitis B envelop antibody, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and serum HBV DNA levels were determined at baseline and subsequently every 12 weeks. Viral mutation tests were performed at baseline for all NA-experienced patients and for patients with virological breakthrough (VBT).

Laboratory assay

Serologic markers of HBV were assessed using a commercially available electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA, Roche Diagnostics, Branchburg, NJ, USA). Serum HBV DNA levels were measured by real-time PCR using the COBAS Amplicor assay (Roche Diagnostics; limit of detection 20 IU/mL). Genotypic analysis was performed with the restriction fragment mass polymorphism (RFMP) method.

Definition

A PVR was defined as above. A virological response (VR) was defined as a decrease in serum HBV DNA to an undetectable level as determined by real-time PCR assay (< 60 IU/mL). VBT was defined as an increase in HBV DNA levels of more than 1 log10 IU/mL, compared to the nadir HBV level achieved during therapy.

Statistical analysis

Median, range, mean and standard deviation (SD) were used to describe statistics as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using Student t test and presented as means ± SD. Nominal variables were compared with Pearson chi-square tests. Multivariate analysis was performed with logistic regression analysis. Time to VR was calculated using a Kaplan-Meier's curve and compared with the long rank test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS Enterprise Guide version 5.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline patient characteristics

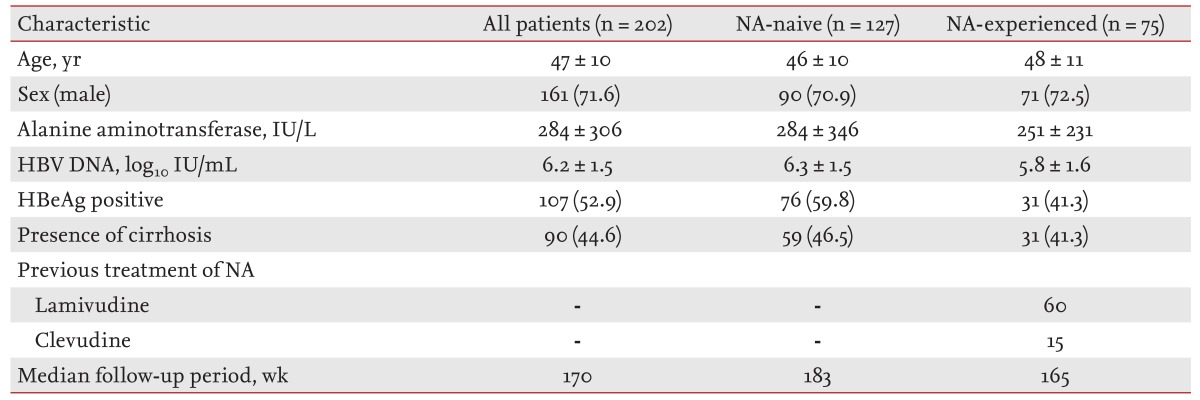

Baseline characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. A total of 202 patients (143 male, 59 female; mean age 47 ± 10 years) were included in this study. The median duration of follow-up was 170 weeks (range, 50 to 333). One hundred seven patients (53.2%) were HBeAg-positive and 90 patients (44.6%) had cirrhosis of the liver. The mean baseline HBV DNA level was 6.2 ± 1.5 log10 IU/mL and the median ALT level was 161 IU/L. There were 75 NA-experienced patients (43.6%).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients.

165Values are presented as mean ± SD or number (%).

NA, nucleos(t)ide-analogue; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBeAg, hepatitis B envelop antigen.

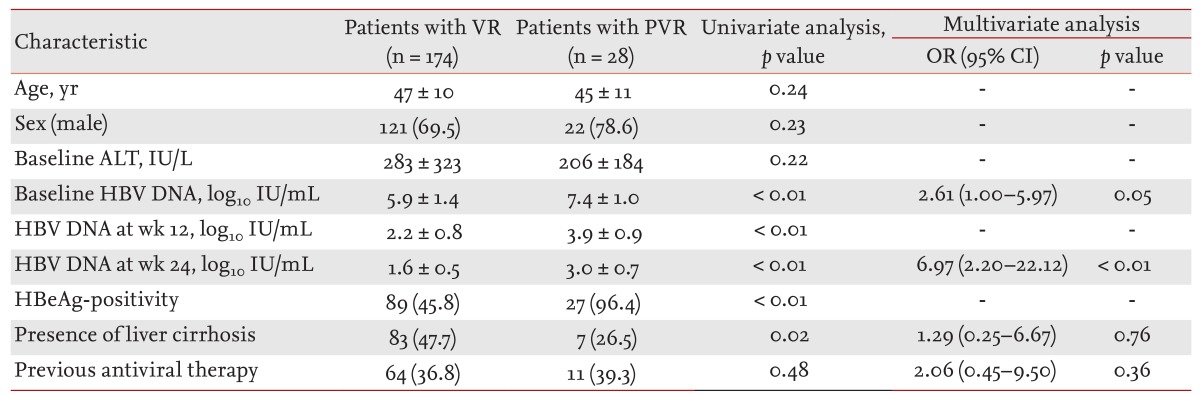

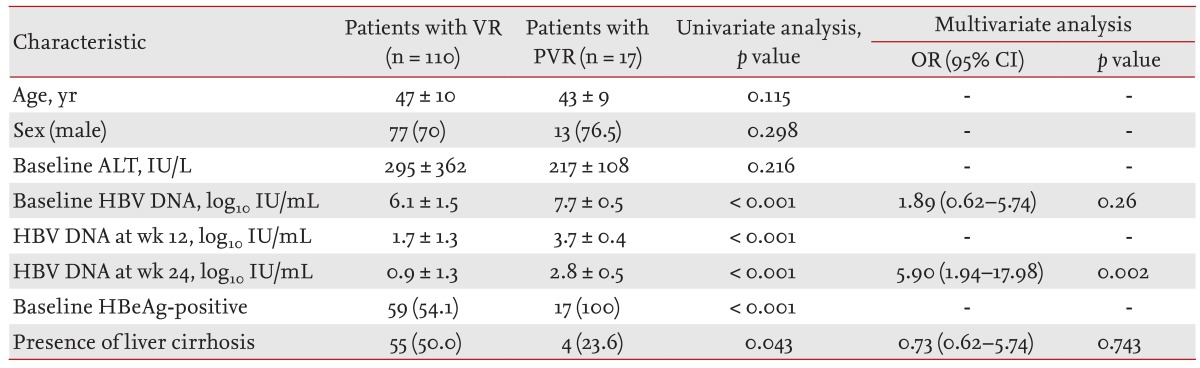

Overall virological responses to ETV therapy and factors associated with PVR

VR was achieved in 174 patients at week 48, while a PVR was seen in 28 patients (13.9%) (Table 2). Univariate analysis identified high serum HBV DNA levels at baseline, week 12 and 24, HBeAg positivity and the absence of liver cirrhosis as significantly associated with PVR (Table 2). Multivariate analysis results demonstrated that high serum HBV DNA levels at baseline and week 24 were independently associated with PVR (Table 2).

Table 2. Baseline and on-treatment factors associated with partial virological response.

Values are presented as mean ± SD or number (%).

VR, virological response; PVR, partial virological response; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBeAg, hepatitis B envelop antigen.

Virological responses to ETV and factors associated with PVR in NA-naive patients

VR was achieved in 110 of 127 NA-naive patients (86.6%) at week 48 (Table 3). High levels of serum HBV DNA at baseline, week 12 and 24, HBeAg positivity and the absence of liver cirrhosis were significantly associated with PVR (p < 0.05; univariate analysis), while multivariate analysis demonstrated that a high level of serum HBV DNA at week 24 was independently associated with PVR.

Table 3. Factors associated with a partial virological response in nucloes(t)ide analogue-naive patients.

Values are presented as mean ± SD or number (%).

VR, virological response; PVR, partial virological response; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBeAg, hepatitis B envelop antigen.

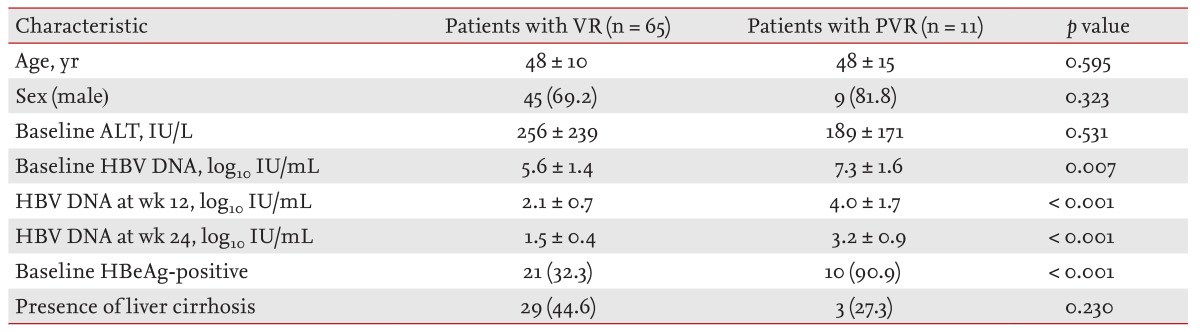

Virological responses to ETV and factors associated with PVR in NA-experienced patients

Sixty-five out of 76 NA-experienced patients (85.8%) achieved a VR at week 48 (Table 4). High serum HBV DNA levels at baseline, week 12 and 24, and HBeAg positivity were significantly associated with PVR by univariate analysis.

Table 4. Factors associated with a partial virological response in nucloes(t)ide analogue-experienced patients.

Values are presented as mean ± SD or number (%).

VR, virological response; PVR, partial virological response; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBeAg, hepatitis B envelop antigen.

Long-term outcomes of patients with PVR to ETV

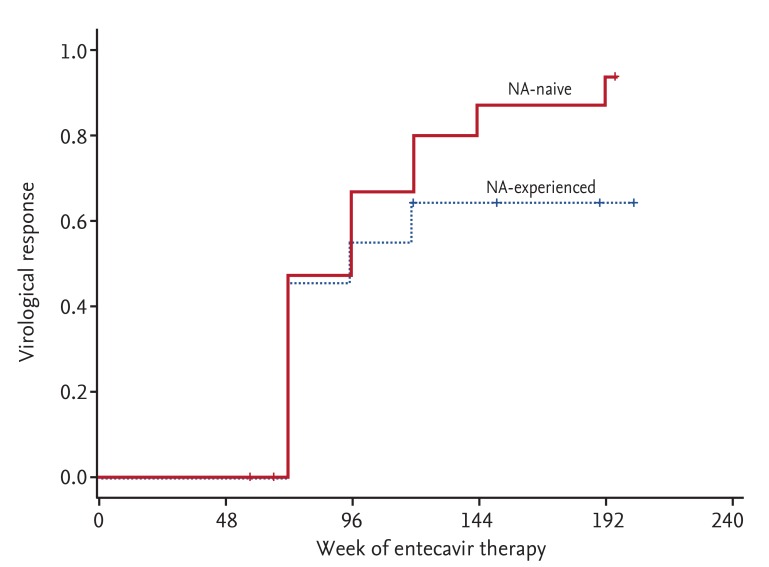

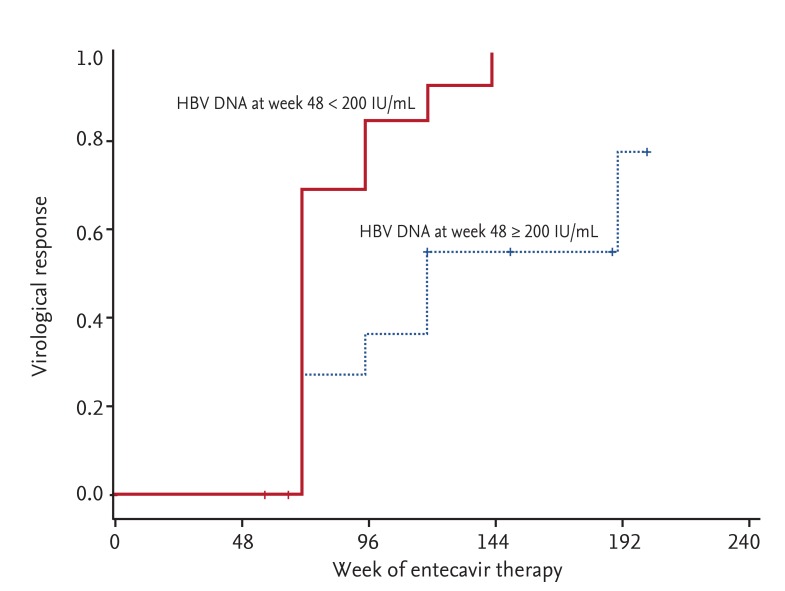

A total of 28 patients experienced PVR to ETV. VR was achieved in 21 of these patients during the follow-up period (median duration of follow-up, 154 weeks). The overall cumulative rates of VR were 46.2%, 61.5%, 73.1%, 77.6%, and 85% at week 72, 96, 120, 144, and 192, respectively. Cumulative rates of VR in NA-naive patients were 46.7%, 66.7%, 80.0%, 86.7% and 93.3% at week 72, 96, 120, 144, and 192, respectively; compared to NA-experienced patients with values of 45.5%, 54.5%, and 63.6% obtained at week 72, 96, and 120, respectively (Fig. 1). NA-experience was not significantly associated with failure of VR in patients with PVR (p = 0.253). No additional cases of VR were achieved after week 120 in NA-experienced patients. Low serum levels of HBV DNA at week 48 (< 200 IU/mL) were associated with subsequent achievement of VR (p = 0.004) (Fig. 2). Resistance to antivirals was identified in two patients who had all undergone previous NA therapy. An RFMP study revealed genotypic mutations to LMV in both cases. No statistically significant risk factors for the development of resistance to antivirals were identified, likely due to the low incidence of antiviral resistance.

Figure 1. The cumulative rates of virological response in nucloes(t)ide analogue (NA)-naive and NA-experienced patients with a partial virological response to entecavir. There was no significant difference in virological response between NA-naive and NA-experienced patients (p = 0.253).

Figure 2. Cumulative rates of virological response dependent on serum hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA at week 48. A high level of serum HBV DNA at week 48 (≥ 200 IU/mL) was significantly associated with failure to achieve a virological response in patients with a partial virological response to entecavir.

DISCUSSION

Patients with a persistently high level of HBV DNA are at greater risk of developing cirrhosis and HCC [2,3]. The long-term suppression of serum HBV DNA without emergence of resistance to antivirals is a key factor in the effective treatment of chronic HBV infection. Patients who demonstrate a PVR to low genetic barrier NAs are at risk of developing antiviral resistance and should be switched to a more potent drug or combination therapy [14]. Clinical guidelines for patients with a PVR to high genetic barrier NAs such as ETV; however, remain the subject of debate.

In this study we evaluated factors associated with PVR to ETV and long-term virological outcomes in such patients, and identified that PVR is associated with a high level of serum HBV DNA at baseline and at week 24. NA-naive patients with PVR had favorable virological outcomes. Serum HBV DNA at week 48 below 200 IU/mL was associated with subsequent achievement of VR for patients with PVR to ETV, and antiviral resistance emerged only in NA-experienced patients.

Rates of PVR to ETV in NA-naive patients have been reported in several studies to be 11.3% to 14.6% [15,16,17]. These studies identify high HBV DNA levels at baseline [15,16], high HBV DNA at week 24 [17], and HBeAg positivity [15] as risk factors for PVR. Most NA-naive patients with a PVR to ETV achieved VR during long-term ETV therapy. Resistance to antivirals, although uncommon in NA-naive patients, occurred mostly in noncompliant patients [15,16,17]. Our study included patients whose adherence to medication was over 80%, and demonstrated results similar to those of previous reports. All NA-naive patients, except for one who was lost to follow-up, achieved VR during continuous ETV therapy. Additional VR was achieved up to 4 years of ETV therapy, and no resistance to antivirals occurred in NA-naive patients during the treatment period.

Few studies of the clinical outcome of NA-experienced patients with a PVR to ETV have been conducted. One such study, which included NA-naive and -experienced patients, reported that the presence of LAM-resistance at baseline and a previous history of LAM resistance were significantly associated with a reduced probability of achieving VR [15]. Yang et al. [18] reported that VR to ETV was significantly lower in NA-experienced patients (80.5%) than in NA-naive patients (96.9%), but achieving VR, even in NA-experienced patients, was significantly associated with a reduced risk of clinical events including HCC. In our study, the VR of NA-experienced patients was as high as 82.7% at week 48, which was associated with HBV DNA levels at baseline, week 24 and antigen-positivity. We found that 63.6% of NA-experienced patients with PVR achieved VR by week 120 of ETV therapy, while antiviral resistance occurred in two of six NA-experienced patients with high HBV DNA (≥ 200 IU/mL) at week 48. Therefore, modification of antiviral therapy should be considered in NA-experienced patients with PVR and high HBV DNA levels.

A particular strength of our study is that we were able to identify virological outcome in the majority of patients owing to the relatively long-term follow-up period employed. In addition, we were able to determine outcomes in NA-experienced patients with PVR. However, the study is limited by the retrospective observational design utilized. We analyzed patients who were treated with ETV for at least 48 weeks, which might exclude patients who had VBT or antiviral resistance before week 48. The development of resistance to antivirals may have been underestimated since mutation analysis was performed only when viral breakthrough was identified. The relatively small number of patients with PVR also limited our capacity to analyze predictive factors for antiviral resistance.

In conclusion, PVR to ETV is associated with a high level of HBV DNA at baseline and at week 24. Almost all of the NA-naive patients with PVR in our study achieved VR without the emergence of resistance to antivirals during continuous ETV therapy, whereas antiviral resistance developed in two out of six NA-experienced patients with serum HBV DNA at week 48 ≥ 200 IU/mL.

KEY MESSAGE

Almost all of the nucloes(t)ide analogue (NA)-naive patients with partial virological response in our study achieved virological response without the emergence of resistance to antivirals during continuous entecavir therapy.

Antiviral resistance developed in two of six NA-experienced patients with serum hepatitis B virus DNA at week 48 ≥ 200 IU/mL.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373:582–592. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo XF, Zhang CX, Liu Y, Wu F, Luo X. Drug-resistant genes at hepatitis B virus polymerase region during entecavir treatment. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2013;35:444–446. doi: 10.3881/j.issn.1000-503X.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papatheodoridis G, Goulis J, Manolakopoulos S, et al. Changes of HBsAg and interferon-inducible protein 10 serum levels in naive HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B patients under 4-year entecavir therapy. J Hepatol. 2014;60:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang TT, Gish RG, de Man R, et al. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1001–1010. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai CL, Shouval D, Lok AS, et al. Entecavir versus lamivudine for patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1011–1020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang TT, Lai CL, Kew Yoon S, et al. Entecavir treatment for up to 5 years in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;51:422–430. doi: 10.1002/hep.23327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiff ER, Lee SS, Chao YC, et al. Long-term treatment with entecavir induces reversal of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:274–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, et al. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;52:886–893. doi: 10.1002/hep.23785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hosaka T, Suzuki F, Kobayashi M, et al. Long-term entecavir treatment reduces hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in patients with hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2013;58:98–107. doi: 10.1002/hep.26180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papatheodoridis GV, Dimou E, Dimakopoulos K, et al. Outcome of hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B on long-term nucleos(t)ide analog therapy starting with lamivudine. Hepatology. 2005;42:121–129. doi: 10.1002/hep.20760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zoulim F, Perrillo R. Hepatitis B: reflections on the current approach to antiviral therapy. J Hepatol. 2008;48(Suppl 1):S2–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai CL, Gane E, Liaw YF, et al. Telbivudine versus lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2576–2588. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korean Association for the Study of the Liver. KASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2012;18:109–162. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2012.18.2.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang CC, Tseng TC, Wang PC, Lin HH, Kao JH. Baseline hepatitis B surface antigen quantitation can predict virologic response in entecavir-treated chronic hepatitis B patients. J Formos Med Assoc. 2014;113:786–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zoutendijk R, Reijnders JG, Brown A, et al. Entecavir treatment for chronic hepatitis B: adaptation is not needed for the majority of naive patients with a partial virological response. Hepatology. 2011;54:443–451. doi: 10.1002/hep.24406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko SY, Choe WH, Kwon SY, et al. Long-term impact of entecavir monotherapy in chronic hepatitis B patients with a partial virologic response to entecavir therapy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1362–1367. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.719927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bang SJ, Kim BG, Shin JW, et al. Clinical course of patients with insufficient viral suppression during entecavir therapy in genotype C chronic hepatitis B. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang SC, Lee CM, Hu TH, et al. Virological response to entecavir reduces the risk of liver disease progression in nucleos(t)ide analogue-experienced HBV-infected patients with prior resistant mutants. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:2154–2163. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]