Abstract

Few large-scale studies have evaluated the effectiveness of angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with masked hypertension (MH) and white coat hypertension (WCH) based on age using real-world blood pressure (BP) data. We used data from the Home BP measurement with Olmesartan Naive patients to Establish Standard Target BP (HONEST) study to investigate the effectiveness of olmesartan-based treatment by patient age (<65 years of age, n=9817; 65–74 years of age, n=6792; ⩾75 years of age, n=4732), focusing on morning home BP (strongly associated with cardiovascular disease and useful for MH and WCH diagnosis). Sixteen weeks of treatment changed morning home BP (mean systolic/diastolic) by −18.1/−9.7, −15.9/−7.4 and −14.2/−6.4 mm Hg and clinic BP by −20.1/−11.3, −17.3/−8.7 and −15.4/−7.2 mm Hg, in these age groups, respectively (P<0.0001). Pulse pressure decreased (−7.8 to −8.8 mm Hg, P<0.0001). Patients aged ⩾80 years experienced similar BP and pulse pressure changes. In patients aged ⩾75 years, mean morning and clinic BP after 16 weeks was 137.5/74.8 and 129.7/70.4 mm Hg, respectively, in MH patients and 132.3/72.2 and 139.7/72.7 mm Hg, respectively, in WCH patients. Regardless of age, only elevated clinic or home BP values decreased to target ranges. The incidence of adverse effects associated with excessive BP lowering was low in all of the age groups. In conclusion, our study suggests that olmesartan-based treatment was safe and useful for managing MH, WCH and sustained hypertension in elderly patients. The lack of a placebo group was a limitation of the study.

Keywords: aging, blood pressure monitoring, masked hypertension, pulse pressure, white coat hypertension

Introduction

White coat hypertension (WCH) and masked hypertension (MH), the diagnosis of which cannot be based on clinic blood pressure (BP) measurements alone, each account for 9–17% of cases in the general population.1 WCH is a term that generally refers to untreated patients. However, WCH occasionally appears in patients receiving treatment, and it has been associated with cardiovascular risk in elderly patients.2,3 MH has been observed in both treated and untreated patients, increasing cardiovascular risk in both cases, and recent guidelines recommend medical treatment according to individual risk for patients with MH.4 How to address the discrepancy in BP measured inside and outside the clinic is a major issue in clinical practice, particularly for the identification of WCH and MH; however, consensus has not been fully attained.

In addition to ambulatory BP monitoring, home BP is a useful indicator in the determination of hypertension categories, including WCH, MH and sustained hypertension5 and in the assessment of risk in individual patients.6 In Japan, self-monitoring of home BP by patients has become an established method for the management of hypertension in clinical practice. However, few large-scale clinical studies involving elderly patients have used home BP data to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of antihypertensive treatments for conditions such as WCH and MH. Cardiovascular events tend to occur most frequently in the morning, along with a peak in ambulatory BP,7 and morning systolic BP (SBP) was the strongest independent predictor of stroke among clinic, 24-h, awake, sleep, evening, pre-awake and morning BP.8 Against this background, with a particular focus on morning home SBP (HSBP), we conducted the Home BP measurement with Olmesartan Naive patients to Establish Standard Target BP (HONEST) study, a prospective, observational study that followed >20 000 patients receiving olmesartan-based antihypertensive treatment for 2 years; the time from the start of treatment to first occurrence of cardiovascular events was the primary endpoint.9

We previously reported the results at 16 weeks for the entire study population (n=21 341).10 Briefly, clinic SBP (CSBP) decreased from 153.6±19.0 to 135.5±15.3 mm Hg after 16 weeks, and HSBP decreased from 151.6±16.4 at baseline to 135.0±13.7 mm Hg. The percentage of patients with MH increased from 11.8 to 24.2%, and the percentage with WCH increased from 5.6 to 11.9%. In this subanalysis, we used the results from the HONEST study for elderly patients at 16 weeks to determine changes in morning HSBP and CSBP, as well as the safety of olmesartan-based treatment in these patients according to age (<65, 65–74 and⩾75 years of age).

Methods

Study protocol

The HONEST study was a large-scale, prospective, observational study with a 2-year follow-up period that ended on 30 September 2012.9 The protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Daiichi Sankyo and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan before the study began. The HONEST study was performed in registered medical institutions and complied with Japanese Good Post-marketing Study Practice and with each institution's internal regulations for clinical studies, and it was registered at http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index.htm (unique trial number, UMIN000002567).

Written informed consent was obtained from all of the study participants at the start of the HONEST study. The participants were olmesartan-naïve patients with essential hypertension. They had no recent history of acute cardiovascular events (for example, myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular interventions) and no planned cardiovascular interventions. The diagnosis of essential hypertension was made by attending physicians without specific criteria regarding BP cut-off values or the patients' use of antihypertensive treatment. Olmesartan (generally 10 or 20 mg per day) was administered at the discretion of each participating physician. No restrictions were placed on previous antihypertensive drug treatment, with the exception of previous olmesartan use, or on the use of combination antihypertensive drug treatment during the study.

The data collected included baseline patient characteristics (for example, disease history and complications), home and clinic BP measurements (SBP/diastolic BP (DBP)), clinical laboratory test values and the incidence of cardiovascular and other adverse events during the study period. The present analysis used data for patients who received olmesartan during the first 16 weeks of the HONEST study.

Home BP measurements

Patients who already owned electronic arm-cuff BP monitors based on the cuff-oscillometric method were registered. All such devices available in Japan have been validated and approved by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. In the HONEST study, the patients were asked at the time of informed consent to measure their BP twice in the morning and twice at bedtime, according to the guidelines of the Japanese Society of Hypertension:11 in the morning (within 1 h of waking, after urinating, before the morning dose, before breakfast and after 1–2 min of resting in a sitting position) and at bedtime (after 1–2 min of rest in a sitting position). In the present subanalysis, only the first morning measurement of home BP, as an average value over 2 days (at baseline and at 16 weeks), was used. The patients were instructed to measure and record home BP values on a sheet of paper and to report these values to their attending physicians. We chose to use data for this specific period (16 weeks) because the present study is based on a previous study,10 the results of which were, in turn, compared with those of another study.12

Definition of hypertension status

The definitions of the hypertension status of the patients were based on European Society of Hypertension guidelines for BP monitoring at home.13 The guidelines state that home BP monitoring can provide information about BP control outside the office and therefore allow for the identification of WCH and MH in patients receiving treatment for hypertension.

We defined hypertension status by clinic and morning home BP as follows: morning hypertension, morning HSBP⩾135 mm Hg; MH, CSBP<140 mm Hg and morning HSBP⩾135 mm Hg; WCH, CSBP⩾140 mm Hg and morning HSBP<135 mm Hg; poorly controlled hypertension, CSBP⩾140 mm Hg and morning HSBP⩾135 mm Hg; and well-controlled hypertension, CSBP<140 mm Hg and morning HSBP<135 mm Hg. At baseline, each defined hypertension group included patients both receiving and not receiving treatment. We reported the same criteria for the diagnosis and classification of patients, including treated patients, in a previous article about the HONEST study.9,10

Safety analysis

Adverse events considered by the study investigators to be related to olmesartan were classified as adverse drug reactions (ADRs). ADRs were classified using the preferred terms from the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed data for BP control in the effectiveness analysis population and for safety data in the safety analysis population. Missing values were not imputed, and only observed values were used in the data analyses. For analysis purposes, we divided the population into three groups by age:<65 years, 65–74 years and ⩾75 years of age. In addition, we also analyzed the subgroup of patients aged ⩾80 years. The patients with chronic kidney disease at baseline were defined as having an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml min−1 per 1.73 m2, proteinuria ⩾2+ on dipstick test, proteinuria 1+ and renal disease as a complication at study entry or both. Estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated by the following formula devised for the Japanese population:14 estimated glomerular filtration rate=194 × age (years)−0.287 × SCr−1.094 ( × 0.739 in women), where serum creatinine (SCr) levels measured within 12 months prior to study onset were used. Continuous variables and categorical variables are expressed as the mean±s.d. and proportions (%), respectively. Trend testing was used to assess trends relating to background factors between age groups. The paired t-test was used to analyze changes in BP and pulse pressure from baseline within age groups. For changes in BP, additional analyses adjusted for concomitant antihypertensive drug use (by drug classes) were also conducted. A McNemar-type test was used to evaluate the effectiveness of olmesartan-based treatment, based on changes in the distribution of patients with well-controlled hypertension and differences in the percentages of patients achieving their target morning HSBP (<135 mm Hg) and CSBP (<140 mm Hg) between baseline and 16 weeks. A two-sided test was used, and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. SAS software, release 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), was used for all of the statistical analyses.

Results

Study profile

The data set in this analysis was used as of April 2012. Over the first 16 weeks of the HONEST study, data were collected from 22 162 patients. Data from 21 571 and 21 341 patients were used for the analyses of safety and effectiveness, respectively.

Patient characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients whose data were used in the effectiveness analysis according to age group. The percentages of patients aged<65, 65–74 and ⩾75 years were 46.0%, 31.8% and 22.2%, respectively. The effectiveness analysis population included 2095 patients (9.8%) aged ⩾80 years.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the effectiveness analysis population (n=21 341).

|

Age at baseline (years)a |

P for trendb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

⩾75 |

|||||

| <65 (n=9817) | 65–74 (n=6792) | (n=4732) | Subgroup ⩾80 (n=2095) | ||

| Age (years) | 54.4±7.8 | 69.5±2.9 | 79.8±4.1 | 83.5±3.4 | <0.0001 |

| Women | 4333 (44.1) | 3595 (52.9) | 2856 (60.4) | 1352 (64.5) | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index (kg m−2) | 24.99±3.93 | 24.02±3.33 | 23.22±3.37 | 22.77±3.40 | <0.0001 |

| Duration of hypertension (years)c | 3.92±4.11 | 5.44±4.49 | 6.72±4.32 | 7.03±4.22 | <0.0001 |

| History | |||||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 384 (3.9) | 509 (7.5) | 523 (11.1) | 250 (11.9) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 209 (2.1) | 354 (5.2) | 403 (8.5) | 198 (9.5) | <0.0001 |

| Complications | |||||

| Dyslipidemia | 4195 (42.7) | 3228 (47.5) | 2061 (43.6) | 824 (39.3) | 0.0284 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1761 (17.9) | 1635 (24.1) | 968 (20.5) | 365 (17.4) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1117 (11.4) | 1476 (21.7) | 1691 (35.7) | 885 (42.2) | <0.0001 |

| Regular alcohol drinkers | 2113 (21.5) | 956 (14.1) | 370 (7.8) | 131 (6.3) | <0.0001 |

| Current smokers | 1808 (18.4) | 601 (8.8) | 209 (4.4) | 59 (2.8) | <0.0001 |

| Patients who had received antihypertensive treatment | 4141 (42.2) | 3701 (54.5) | 2890 (61.1) | 1315 (62.8) | <0.0001 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 2910 (29.6) | 2647 (39.0) | 2133 (45.1) | 972 (46.4) | <0.0001 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 1697 (17.3) | 1604 (23.6) | 1234 (26.1) | 534 (25.5) | <0.0001 |

| β-Blockers | 492 (5.0) | 474 (7.0) | 370 (7.8) | 175 (8.4) | <0.0001 |

| Diuretics | 408 (4.2) | 420 (6.2) | 402 (8.5) | 203 (9.7) | <0.0001 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 274 (2.8) | 288 (4.2) | 218 (4.6) | 103 (4.9) | <0.0001 |

| α-Blockers | 143 (1.5) | 152 (2.2) | 159 (3.4) | 65 (3.1) | <0.0001 |

| No. of previous antihypertensive drugs | 0.6±0.8 | 0.8±0.9 | 1.0±1.0 | 1.0±1.0 | <0.0001 |

Mean±s.d. or n (%).

Data were compared between patients aged <65, 65–74 and ⩾75 years. The Cochran–Armitage test was used for categorical variables and the Jonckheere–Terpstra test for continuous variables.

Recorded as 10 years for patients who had hypertension for ⩾10 years.

There was an association between increased age and a longer duration of hypertension, being female, a history of cerebro and cardiovascular disease, and concomitant chronic kidney disease (trend P<0.0001 for all comparisons). As age increased, the percentages of patients with a smoking or drinking habit decreased (trend P<0.0001 for all comparisons).

Administration status of antihypertensive drugs

The percentage of patients who had received antihypertensive treatment immediately before the start of olmesartan treatment was 42.2% in those aged<65 years, 54.5% in those aged 65–74 years and 61.1% in those aged ⩾75 years (Table 1). Calcium channel blockers were most frequently used in all of the age groups. For all antihypertensive drugs, the percentage of patients who received previous antihypertensive treatment was highest in the patients aged ⩾75 years (Table 1).

The daily dose of olmesartan slightly increased from baseline to 16 weeks in all three age groups: from 17.8±6.6 to 18.6±7.9 mg in patients aged<65 years; from 18.3±7.2 to 18.8±8.3 mg in patients aged 65–74 years; and from 18.8±7.7 to 19.4±8.9 mg in patients aged ⩾75 years. Table 2 shows the use of concomitant antihypertensive drugs. In all of the age groups, calcium channel blockers were the most frequently used. The percentage of patients receiving concomitant antihypertensive drugs increased as age increased. In all of the age groups, the percentage of patients receiving concomitant antihypertensive drugs increased after 16 weeks from baseline. The number of antihypertensive drugs, including olmesartan, used at baseline and after 16 weeks was 1.4±0.7 and 1.5±0.7 in patients aged <65 years; 1.5±0.7 and 1.6±0.8 in patients aged 65–74 years and 1.7±0.8 and 1.7±0.9 in patients aged ⩾75 years, respectively.

Table 2. Administration status of concomitant antihypertensive agentsa.

|

Age at baseline (years) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <65 | 65–74 |

⩾75 |

||

| (n=9817) | (n=6792) | (n=4732) | ⩾80 subgroup (n=2095) | |

| At start of olmesartan treatment | ||||

| Receiving concomitant antihypertensive agents ⩾1 | 3156 (32.1) | 2825 (41.6) | 2299 (48.6) | 1054 (50.3) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 2745 (28.0) | 2484 (36.6) | 2016 (42.6) | 916 (43.7) |

| β-Blockers | 464 (4.7) | 450 (6.6) | 362 (7.7) | 169 (8.1) |

| Diuretics | 327 (3.3) | 311 (4.6) | 323 (6.8) | 162 (7.7) |

| α-Blockers | 139 (1.4) | 142 (2.1) | 155 (3.3) | 63 (3.0) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 105 (1.1) | 107 (1.6) | 97 (2.0) | 42 (2.0) |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 54 (0.6) | 53 (0.8) | 53 (1.1) | 23 (1.1) |

| Other | 29 (0.3) | 19 (0.3) | 26 (0.5) | 13 (0.6) |

| No. of antihypertensive drugs (including olmesartan) | 1.4±0.7 | 1.5±0.7 | 1.7±0.8 | 1.7±0.8 |

| At 16 weeks | ||||

| Receiving concomitant antihypertensive agents ⩾1 | 3934 (40.1) | 3143 (46.3) | 2511 (53.1) | 1132 (54.0) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 3408 (34.7) | 2773 (40.8) | 2208 (46.7) | 990 (47.3) |

| β-Blockers | 529 (5.4) | 474 (7.0) | 383 (8.1) | 180 (8.6) |

| Diuretics | 551 (5.6) | 451 (6.6) | 401 (8.5) | 193 (9.2) |

| α-Blockers | 171 (1.7) | 164 (2.4) | 174 (3.7) | 70 (3.3) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 105 (1.1) | 105 (1.5) | 99 (2.1) | 42 (2.0) |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 58 (0.6) | 53 (0.8) | 50 (1.1) | 23 (1.1) |

| Other | 45 (0.5) | 32 (0.5) | 35 (0.7) | 17 (0.8) |

| No. of antihypertensive drugs (including olmesartan) | 1.5±0.7 | 1.6±0.8 | 1.7±0.9 | 1.7±0.9 |

n (%).

Changes in BP and pulse pressure by age group

Table 3 shows changes in BP from baseline to after 16 weeks of olmesartan-based treatment. After 16 weeks of olmesartan-based treatment, morning home BP and clinic BP (both SBP and DBP) decreased significantly in patients aged<65, 65–74, ⩾75 and ⩾80 years (all P<0.0001). Analyses adjusted for concomitant antihypertensive drug use (by drug classes) showed essentially the same results (data not shown).

Table 3. Changes in morning home BP and clinic BP from baseline after 16 weeks of olmesartan-based treatment by age group.

| Age (years) |

BP (mm Hg)a |

Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 16 Weeks | ||

| <65 (n=8643) | |||

| Morning home | 151.8±16.5/91.7±10.9 | 133.8±13.2/82.0±9.5b | −18.1±17.5/−9.7±10.9* |

| Clinic | 155.0±18.9/92.1±12.4 | 134.9±14.8/80.8±10.3c | −20.1±20.0/−11.3±12.9* |

| 65–74 (n=6100) | |||

| Morning home | 150.9±16.1/84.4±10.5 | 135.1±13.9/77.0±9.3 | −15.9±17.7/−7.4±10.3* |

| Clinic | 152.6±18.8/84.3±12.2 | 135.3±15.5/75.6±10.3d | −17.3±19.9/−8.7±12.1* |

| ⩾75 (n=4279) | |||

| Morning home | 151.6±16.1/81.0±10.8 | 137.4±14.0/74.6±9.4b | −14.2±18.0/−6.4±10.7* |

| Clinic | 152.2±18.8/80.5±12.4 | 136.8±15.8/73.3±10.3 | −15.4±20.2/−7.2±12.3* |

| ⩾80 subgroup (n=1864) | |||

| Morning home | 151.9±16.6/80.1±10.9 | 138.0±14.0/74.0±9.6b | −13.8±18.2/−6.1±10.8* |

| Clinic | 152.3±19.3/79.5±12.4 | 137.3±15.9/72.7±10.4 | −15.0±20.1/−6.8±12.4* |

Abbreviation: BP, blood pressure.

Mean±s.d.

Two patients.

One patient.

Three patients had missing values for diastolic blood pressure.

P<0.0001 for both systolic and diastolic BP (paired t-test).

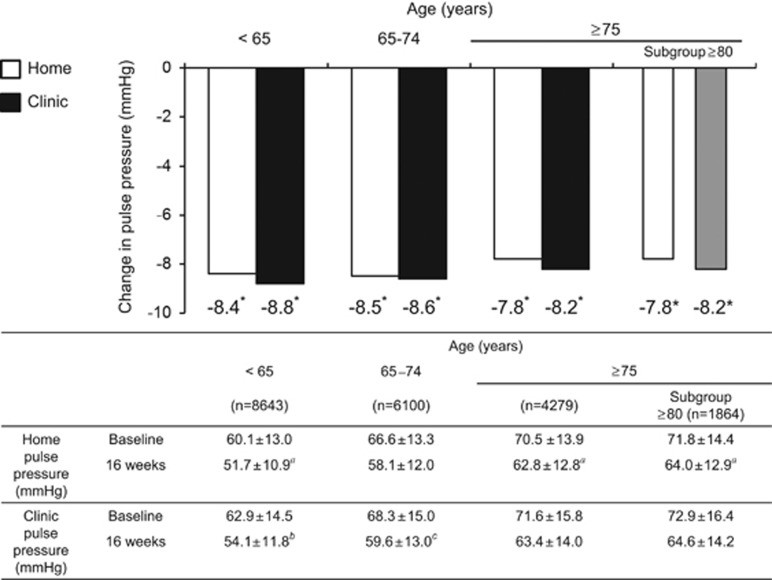

Figure 1 shows changes in pulse pressure. Morning home pulse pressure and clinic pulse pressure decreased significantly in patients aged<65, 65–74, ⩾75 and ⩾80 years (all P<0.0001).

Figure 1.

Changes in pulse pressure from baseline after 16 weeks of olmesartan treatment by age group. *P<0.0001 (paired t-test). aTwo patients, bOne patient and cThree patients had missing values.

Antihypertensive effectiveness and sustained 24-h BP-lowering effects of olmesartan-based treatment by age group

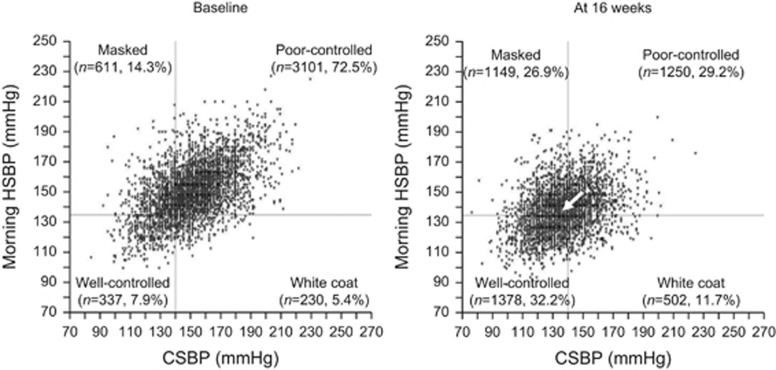

The distribution of patients with different types of hypertension, based on CSBP (cut-off value, 140 mm Hg) and morning HSBP (cut-off value, 135 mm Hg) at baseline and after 16 weeks of olmesartan-based treatment, was as follows. The percentages of patients with poorly controlled and well-controlled hypertension changed from 76.9% to 23.4% and from 7.6% to 42.6%, respectively, in patients aged <65 years; from 73.2% to 24.3% and from 8.4% to 38.4%, respectively, in patients aged 65–74 years; and from 72.5% to 29.2% and from 7.9% to 32.2%, respectively, in patients aged ⩾75 years (Figure 2). In all of the age groups, the distribution of patients with different types of hypertension changed significantly after 16 weeks (all P<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Distribution of well-controlled hypertension, white coat hypertension, masked hypertension and poorly controlled hypertension, defined by morning home systolic blood pressure (morning HSBP) and clinic systolic blood pressure (CSBP) in patients aged ⩾75 years. There was a significant difference between baseline and after 16 weeks of olmesartan treatment (P<0.0001, McNemar-type test). The arrows show changes in average systolic blood pressure from baseline to 16 weeks (arrow tail, average BP at baseline; arrowhead, average BP after 16 weeks). The target morning HSBP and CSBP were <135 mm Hg and <140 mm Hg, respectively.

The percentage of patients aged <65 years who achieved the target SBP increased from 17.5% at baseline to 64.9% after 16 weeks for CSBP (target, <140 mm Hg) and from 13.1 to 54.4% for morning HSBP (target, <135 mm Hg). Similarly, the percentage of patients aged 65–74 years who achieved the target SBP increased from 21.0 to 63.5% for CSBP and from 14.2 to 50.5% for morning HSBP. The percentage of patients aged ⩾75 years who achieved the target SBP increased from 22.2 to 59.1% for CSBP and from 13.3 to 43.9% for morning HSBP (Figure 2). These changes in the percentages of patients achieving target CSBP and morning HSBP and the consequent changes in the proportions with morning hypertension were significant in all three age groups (all P<0.0001).

Analyses based on hypertension status, using both SBP and DBP, showed essentially same results as those using SBP only (data not shown).

Changes in BP by hypertension status in patients aged ⩾75 years

Table 4 shows changes in BP according to hypertension status in patients aged ⩾75 years. After 16 weeks, morning HSBP in the MH group decreased from 148.7 to 137.5 mm Hg (P<0.0001). CSBP in the WCH group decreased from 151.6 to 139.7 mm Hg (P<0.0001). However, non-elevated BP (that is, CSBP in the MH group and morning HSBP in the WCH group) remained within an acceptable range after 16 weeks of olmesartan-based treatment. There was a similar trend in DBP in the MH and WCH groups.

Table 4. Changes in BP from baseline after 16 weeks of olmesartan-based treatment in patients aged⩾75 years.

|

Morning home BPa |

P-valueb |

Clinic BPa |

P-valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 16 Weeks | Baseline | 16 Weeks | |||

| Patients with masked hypertension (n=611) | ||||||

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 148.7±11.3 | 137.5±14.3 | <0.0001 | 129.0±8.5 | 129.7±14.9 | 0.2462 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 79.7±9.7 | 74.8±9.6 | <0.0001 | 71.3±10.0 | 70.4±10.3 | 0.0219 |

| Patients with white coat hypertension (n=230) | ||||||

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 128.0±5.3 | 132.3±12.6 | <0.0001 | 151.6±11.0 | 139.7±16.5 | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 71.2±8.1 | 72.2±9.7 | 0.0898 | 78.5±10.9 | 72.7±10.4 | <0.0001 |

| Patients with poor-controlled hypertension (n=3101) | ||||||

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 156.8±13.2 | 138.7±13.8 | <0.0001 | 159.8±14.3 | 138.8±15.4 | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 83.2±10.3 | 75.0±9.3c | <0.0001 | 83.7±11.6 | 74.2±10.1 | <0.0001 |

| Patients with well-controlled hypertension (n=337) | ||||||

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 124.5±7.3 | 129.0±12.4 | <0.0001 | 124.4±10.0 | 128.9±14.4 | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 70.2±8.2 | 72.0±9.5 | 0.0004 | 69.1±9.0 | 70.9±9.9 | 0.0019 |

Abbreviation: BP, blood pressure.

Mean±s.d.

Data analyzed by paired t-test.

Two patients had missing values.

After 16 weeks of olmesartan treatment, morning home BP in the group with poorly controlled hypertension decreased from 156.8/83.2 to 138.7/75.0 mm Hg, and clinic BP decreased from 159.8/83.7 to 138.8/74.2 mm Hg (both P<0.0001). In the group with well-controlled hypertension, good control of morning home BP and clinic BP (SBP and DBP) was maintained at 16 weeks after the start of olmesartan treatment. Analyses adjusted for concomitant antihypertensive drug use (by drug classes) showed essentially the same results (data not shown). Analyses based on hypertension status, using both SBP and DBP, showed essentially same results as those using SBP only (data not shown).

Safety

The incidences of ADRs were 1.10%, 1.57% and 1.44% in patients aged<65, 65–74 and ⩾75 years, respectively; therefore, the incidence of ADRs tended to increase with age (trend P=0.0341). However, the incidences of ADRs associated with excessive BP lowering (that is, dizziness, postural dizziness, hypotension, orthostatic hypotension and decreased BP) were 0.46%, 0.47%, and 0.52% in each age group, respectively, and therefore did not tend to increase with age (trend P=0.6583). In patients aged ⩾80 years, the incidences of overall ADRs and those associated with excessive BP lowering were 1.70% and 0.76%, respectively.

Adverse renal events occurred in two patients (nephrotic syndrome and chronic renal failure) who were receiving concomitant ACE inhibitors; however, a causal relationship with olmesartan was denied by the attending physicians.

Discussion

The HONEST study was the first large-scale clinical study to investigate the antihypertensive effectiveness and safety profile of olmesartan-based treatment using home BP and clinic BP data from patients, including those aged ⩾75 years, in a real-world clinical setting. The study enrolled patients who required olmesartan-based treatment to control home or clinic BP, according to the judgment of an attending physician. Olmesartan-based treatment was effective in lowering both morning home BP and clinic BP when they were elevated, as well as pulse pressure, regardless of patient age.

In patients aged ⩾75 years, morning home BP in the MH group and clinic BP in the WCH group decreased to levels close to the target BP defined by JSH 2009 (morning home BP <135/85 mm Hg and clinic BP <140/90 mm Hg).11 In contrast, non-elevated clinic BP in the MH group and morning home BP in the WCH group remained within an acceptable range by treatment. Moreover, the incidence of ADRs associated with excessive BP lowering, which is of particular concern when treating elderly patients, did not increase according to age.

In Japan, home BP monitoring is more widely conducted than ambulatory BP monitoring in the management of hypertension.15 The Hisayama study, which evaluated the home BP of 2915 patients, showed that 6.9% had WCH, and 21.9% had MH, and in both groups, sustained hypertension was associated with increased risks of carotid intima media thickness and carotid atherosclerosis.16

In the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial, which involved elderly hypertensive patients aged ⩾80 years, 112 patients had undergone ambulatory BP monitoring at baseline.3 The percentage of patients with WCH was high (50%). After treatment with indapamide and perindopril, the patients' morning HSBP decreased by 6 mm Hg and their DBP by 5 mm Hg compared with the placebo group, and all-cause mortality and the incidence of cardiovascular events also decreased.3 Therefore, antihypertensive drug therapy was considered useful even for patients with WCH, and it was expected to be particularly beneficial in elderly patients.

Epidemiological studies have shown that MH, including nocturnal and morning hypertension, is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.17 In an analysis of ambulatory BP monitoring data from the International Database of Ambulatory BP in Relation to Cardiovascular Outcomes, which investigated the relationship between morning surges and cardiovascular events, no significant differences were found in nocturnal BP between groups with and without morning surges, but there was a significant difference in morning BP.18 Therefore, although morning hypertension is different from morning surge, morning home BP might be more useful as an indicator in clinical practice. MH is frequently observed in elderly patients, and it was associated with increased risk of stroke.19 For the prevention of cardiovascular disease, 24-h management of BP, including morning BP, is considered important. However, there have been no data from large-scale studies conducted in daily clinical settings that have investigated the effectiveness of ARBs on MH in elderly patients.

In the present study, morning HSBP and CSBP decreased to levels close to 135 mm Hg after 16 weeks of olmesartan-based treatment, regardless of patient age. Because morning HSBP and CSBP similarly achieved their targets, the results indicated the sustained 24-h BP-lowering effects of olmesartan. In contrast, DBP, both morning home and clinic, decreased to <85 mm Hg in all the age groups. Regarding the risk of excessive BP lowering, the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program study investigators reported that lowering DBP to <60 mm Hg increased the risk of a cardiovascular accident.20

The increased risk of cardiovascular disease is a concern when treating hypertensive patients with concomitant cardiovascular disease. For example, following the results of a subanalysis of the Systolic Hypertension in Europe study, caution has been urged when lowering DBP to <70 mm Hg in patients with systolic hypertension and concomitant ischemic heart disease.21 The J-curve phenomenon has been reported between DBP and the risk of myocardial infarction in hypertensive patients with concomitant coronary artery disease,22 as well as between SBP and the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with concomitant obstructive arteriosclerosis.23

It is uncertain whether the J-curve phenomenon should be considered when non-elevated BP is lowered by antihypertensive treatment; that is, in patients with MH, non-elevated clinic BP can be lowered excessively when the target morning home BP is achieved. Similarly, in patients with WCH, non-elevated morning home BP can be lowered excessively when the target clinic BP is achieved. Moreover, in elderly patients, who often have concomitant cardiovascular disease, excessive lowering of DBP when the target SBP is achieved can be a major issue.

In the present study, even in patients aged ⩾75 years with a high risk of concomitant cardiovascular disease, there was no excessive lowering of clinic BP in the MH group or of home BP in the WCH group. Moreover, the incidence of ADRs associated with excessive BP lowering was low, consistent with the results of small-scale studies performed in Japan that showed no increases in adverse events as a result of excessive BP-lowering effects in elderly hypertensive patients.24,25 Possible explanations include the gradual lowering of BP, as recommended by hypertension guidelines,11 or the possible exclusion of patients with histories of adverse events resulting from excessive BP-lowering effects, such as postural hypotension. The results of the present study accounted for the treatment decisions made by physicians in clinical practice and might therefore differ from the results of interventional studies in which strict BP targets have been defined. Therefore, the results suggest that olmesartan could be a useful option in the treatment of hypertension, including home BP management, in elderly patients.

In the present study, pulse pressure decreased after olmesartan-based treatment in all of the age groups, including patients aged ⩾75 years. Increased pulse pressure in elderly hypertensive patients is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease that is not associated with SBP.26,27 Antihypertensive drugs, particularly renin–angiotensin–aldosterone inhibitors, can improve pulse pressure in elderly hypertensive patients.28,29 In an analysis of seven double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of olmesartan, Giles and Robinson30 reported that olmesartan was effective in lowering pulse pressure in patients aged ⩾65 years to a similar extent as in those aged<65 years. This finding was consistent with our results that olmesartan lowered pulse pressure regardless of patient age. Moreover, in the present study, reductions in both home and clinic pulse pressure were observed even in patients aged ⩾80 years, without excessive BP lowering. The results that olmesartan-based treatment improved morning BP and pulse pressure even in elderly patients aged ⩾80 years, who often have morning surges and morning hypertension, suggested that olmesartan-based treatment was useful for reducing cardiovascular risk in elderly patients.

In the Jichi Morning Hypertension Research study, which divided patients under treatment into four groups according to home and clinic BP, using the same cut-off values that we used in the present study, the percentage of patients with well-controlled hypertension was 21.1%.31 Although a simple comparison might not be appropriate, the percentage of patients with well-controlled hypertension was higher in all of the age groups in the present study after 16 weeks of olmesartan treatment (32.2–42.6%). This finding was considered to be associated with the potent and sustained 24-h BP-lowering effects of olmesartan.

The present study included 1503 patients who had well-controlled BP at baseline. Of these patients, 130 had not received antihypertensive treatment, had no history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes or chronic kidney disease, and did not meet the criteria for hypertension (that is, clinic DBP⩾90 mm Hg and morning home DBP⩾85 mm Hg). These patients were being followed up because of their histories of hypertension. Because of fluctuations in BP, they did not meet the criteria for hypertension at the time that they started olmesartan treatment. However, olmesartan-based treatment was started at the discretion of their attending physicians.

The present study had two main limitations. First, the HONEST study was an observational study of olmesartan-based treatment without a comparison group; therefore, effects other than those of olmesartan (for example, regression toward the mean) might have affected the results. However, the additional analysis, adjusted for concomitant antihypertensive drug use showed essentially the same results. The possibility of a placebo effect on the magnitude of BP changes cannot be discounted, so the findings of the present study must be verified by placebo-controlled, randomized studies. However, home BP measurements have been reported to be highly reproducible and subject to minimal placebo effects.32 In addition, the antihypertensive effectiveness of olmesartan-based treatment observed in this study was consistent with the results of a previous double-blind clinical trial, which showed improvement in pulse pressure in elderly patients.30 We believe that the results of this study could be useful in clinical practice because the data were obtained in a daily clinical setting by measuring home BP. Furthermore, a large number of patients aged ⩾75 years were included.

Second, the definitions of BP control status used by attending physicians for both treated and untreated hypertensive patients in the present study were inconsistent with the stricter definitions used in previous studies involving general populations. However, regarding diagnostic accuracy, home BP is considered a reliable alternative to ambulatory BP in the diagnosis of hypertension and in the detection of WCH and MH in both untreated and treated persons.5

In conclusion, the present study showed that the ARB olmesartan, used alone or in combination with other antihypertensive drugs, was effective in lowering morning home BP and clinic BP when they were elevated, as well as pulse pressure, regardless of patient age, in a real-world clinical setting. The incidence of ADRs associated with excessive BP lowering was low. Therefore, olmesartan-based treatment has been useful in the management of elderly patients with hypertension in various settings in clinical practice, including MH and WCH, if they must be treated.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the numerous investigators, fellows, nurses and research coordinators who participated in the HONEST study at each of the study sites. We also gratefully acknowledge their contribution to the study. TK, KK, IS, ST and KS have received honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo. KK has received research funding from Daiichi Sankyo. YM and YO are employees of Daiichi Sankyo. The study was supported by funding for data collection and statistical analysis by Daiichi Sankyo.

References

- Fagard RH, Cornelissen VA. Incidence of cardiovascular events in white-coat, masked and sustained hypertension vs true normotension: a meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2007;25:2193–2198. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282ef6185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin SS, Thijs L, Hansen TW, Li Y, Boggia J, Kikuya M, Björklund-Bodegård K, Ohkubo T, Jeppesen J, Torp-Pedersen C, Dolan E, Kuznetsova T, Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Tikhonoff V, Malyutina S, Casiglia E, Nikitin Y, Lind L, Sandoya E, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, Imai Y, Wang J, Ibsen H, O'Brien E, Staessen JA. International Database on Ambulatory Blood Pressure in Relation to Cardiovascular Outcomes Investigators Significance of white-coat hypertension in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension: a meta-analysis using the International Database on Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring in Relation to Cardiovascular Outcomes population. Hypertension. 2012;59:564–571. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.180653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulpitt CJ, Beckett N, Peters R, Staessen JA, Wang JG, Comsa M, Fagard RH, Dumitrascu D, Gergova V, Antikainen RL, Cheek E, Rajkumar C. Does white coat hypertension require treatment over age 80?: results of the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial Ambulatory Blood Pressure Side Project. Hypertension. 2013;61:89–94. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.191791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redón J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M, Christiaens T, Cifkova R, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Galderisi M, Grobbee DE, Jaarsma T, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, Ruilope LM, Schmieder RE, Sirnes PA, Sleight P, Viigimaa M, Waeber B, Zannad F. Task Force Members 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) J Hypertens. 2013;31:1281–1357. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000431740.32696.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasothimiou EG, Tzamouranis D, Rarra V, Roussias LG, Stergiou GS. Diagnostic accuracy of home vs ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in untreated and treated hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:750–755. doi: 10.1038/hr.2012.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hänninen MR, Niiranen TJ, Puukka PJ, Johansson J, Jula AM. Prognostic significance of masked and white-coat hypertension in the general population: the Finn-Home Study. J Hypertens. 2012;30:705–712. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328350a69b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller JE, Tofler GH, Stone PH. Circadian variation and triggers of onset of acute cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 1989;79:733–743. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.4.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kario K, Ishikawa J, Pickering TG, Hoshide S, Eguchi K, Morinari M, Hoshide Y, Kuroda T, Shimada K. Morning hypertension: the strongest independent risk factor for stroke in elderly hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res. 2006;29:581–587. doi: 10.1291/hypres.29.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito I, Kario K, Kushiro T, Teramukai S, Zenimura N, Hiramatsu K, Kobayashi F, Shimada K. Rationale, study design, baseline characteristics and blood pressure at 16 weeks in the HONEST Study. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:177–182. doi: 10.1038/hr.2012.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kario K, Saito I, Kushiro T, Teramukai S, Ishikawa Y, Hiramatsu K, Kobayashi F, Shimada K. Effect of the angiotensin II receptor antagonist olmesartan on morning home blood pressure in hypertension: HONEST Study at 16 weeks. J Hum Hypertens. 2013;27:721–728. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2013.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogihara T, Kikuchi K, Matsuoka H, Fujita T, Higaki J, Horiuchi M, Imai Y, Imaizumi T, Ito S, Iwao H, Kario K, Kawano Y, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Kimura G, Matsubara H, Matsuura H, Naruse M, Saito I, Shimada K, Shimamoto K, Suzuki H, Takishita S, Tanahashi N, Tsuchihashi T, Uchiyama M, Ueda S, Ueshima H, Umemura S, Ishimitsu T, Rakugi H. Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee The Japanese society of hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2009) Hypertens Res. 2009;32:3–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kario K, Sato Y, Shirayama M, Takahashi M, Shiosakai K, Hiramatsu K, Komiya M, Shimada K. Inhibitory effects of azelnidipine tablets on morning hypertension. Drugs RD. 2013;13:63–73. doi: 10.1007/s40268-013-0006-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, Bilo G, de Leeuw P, Imai Y, Kario K, Lurbe E, Manolis A, Mengden T, O'Brien E, Ohkubo T, Padfield P, Palatini P, Pickering T, Redon J, Revera M, Ruilope LM, Shennan A, Staessen JA, Tisler A, Waeber B, Zanchetti A, Mancia G. ESH Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring European Society of Hypertension guidelines for blood pressure monitoring at home: a summary report of the Second International Consensus Conference on Home Blood Pressure Monitoring. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1505–1526. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328308da66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee of CKD Initiative, Japanese Society of Nephrology Clinical practice guidebook for diagnosis and treatment of chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2009;13:187–256. [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y, Obara T, Asamaya K, Ohkubo T. The reason why home blood pressure measurements are preferred over clinic or ambulatory blood pressure in Japan. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:661–672. doi: 10.1038/hr.2013.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara M, Arima H, Ninomiya T, Hata J, Hirakawa Y, Doi Y, Yonemoto K, Mukai N, Nagata M, Ikeda F, Matsumura K, Kitazono T, Kiyohara Y. White-coat and masked hypertension are associated with carotid atherosclerosis in a general population: the Hisayama study. Stroke. 2013;44:1512–1517. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen TW, Kikuya M, Thijs L, Björklund-Bodegård K, Kuznetsova T, Ohkubo T, Richart T, Torp-Pedersen C, Lind L, Jeppesen J, Ibsen H, Imai Y, Staessen JA. IDACO Investigators Prognostic superiority of daytime ambulatory over conventional blood pressure in four populations: a meta-analysis of 7030 individuals. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1554–1564. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3281c49da5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Thijs L, Hansen TW, Kikuya M, Boggia J, Richart T, Metoki H, Ohkubo T, Torp-Pedersen C, Kuznetsova T, Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Tikhonoff V, Malyutina S, Casiglia E, Nikitin Y, Sandoya E, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, Ibsen H, Imai Y, Wang J, Staessen JA. International Database on Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring in Relation to Cardiovascular Outcomes Investigators Prognostic value of the morning blood pressure surge in 5645 subjects from 8 populations. Hypertension. 2010;55:1040–1048. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.137273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kario K, Pickering TG, Umeda Y, Hoshide S, Hoshide Y, Morinari M, Murata M, Kuroda T, Schwartz JE, Shimada K. Morning surge in blood pressure as a predictor of silent and clinical cerebrovascular disease in elderly hypertensives: a prospective study. Circulation. 2003;107:1401–1406. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000056521.67546.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somes GW, Pahor M, Shorr RI, Cushman WC, Applegate WB. The role of diastolic blood pressure when treating isolated systolic hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2004–2009. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.17.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagard RH, Staessen JA, Thijs L, Celis H, Bulpitt CJ, de Leeuw PW, Leonetti G, Tuomilehto J, Yodfat Y. On-treatment diastolic blood pressure and prognosis in systolic hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1884–1891. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.17.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messerli FH, Mancia G, Conti CR, Hewkin AC, Kupfer S, Champion A, Kolloch R, Benetos A, Pepine CJ. Dogma disputed: can aggressively lowering blood pressure in hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease be dangerous. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:884–893. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-12-200606200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavry AA, Anderson RD, Gong Y, Denardo SJ, Cooper-Dehoff RM, Handberg EM, Pepine CJ. Outcomes among hypertensive patients with concomitant peripheral and coronary artery disease: findings from the International VErapamil-SR/Trandolapril Study. Hypertension. 2010;55:48–53. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.142240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito I, Kushiro T, Hirata K, Sato Y, Kobayashi F, Sagawa K, Hiramatsu K, Komiya M. The use of olmesartan medoxomil as monotherapy or in combination with other antihypertensive agents in elderly hypertensive patients in Japan. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:272–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito I, Kushiro T, Zenimura N, Kaku M, Matsushita Y, Sagawa K, Hiramatsu K, Komiya M.Special survey of Olmetec Tablet (olmesartan medoxomil) for long-term use—Safety and efficacy in patients less than and over 65 years and especially those over 75 years of age during a 2-year administration J Clin Ther Med 200925141–164.in Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Chae CU, Pfeffer MA, Glynn RJ, Mitchell GF, Taylor JO, Hennekens CH. Increased pulse pressure and risk of heart failure in the elderly. JAMA. 1999;281:634–639. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacher J, Staessen JA, Girerd X, Gasowski J, Thijs L, Liu L, Wang JG, Fagard RH, Safar ME. Pulse pressure not mean pressure determines cardiovascular risk in older hypertensive patients. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1085–1089. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.8.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo JL., Jr Systolic hypertension, arterial stiffness, and vascular damage: role of the renin-angiotensin system. Blood Press Monit. 2000;5 (Suppl 2:S7–S11. doi: 10.1097/00126097-200010002-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin SS. Is there a preferred antihypertensive therapy for isolated systolic hypertension and reduced arterial compliance. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2000;2:253–259. doi: 10.1007/s11906-000-0008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles TD, Robinson TD. Effects of olmesartan medoxomil on systolic blood pressure and pulse pressure in the management of hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:690–695. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kario K, Eguchi K, Umeda Y, Hoshide S, Hoshide Y, Morinari M, Murata M, Kuroda T, Schwartz JE, Shimada K. Morning surge in blood pressure as a predictor of silent and clinical cerebrovascular disease in elderly hypertensives. Circulation. 2003;108:e72–e73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000056521.67546.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y, Ohkubo T, Hozawa A, Tsuji I, Matsubara M, Araki T, Chonan K, Kikuya M, Satoh H, Hisamachi S, Nagai K. Usefulness of home blood pressure measurements in assessing the effect of treatment in a single-blind placebo-controlled open trial. J Hypertens. 2001;19:179–185. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200102000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]