Abstract

Objective:

The study aims were to investigate secular trends in antiepileptic drug (AED) use in women during pregnancy, and to compare the use of first- and second-generation AEDs.

Methods:

Study participants consisted of female Florida Medicaid beneficiaries, older than 15 years, and pregnant within the time period 1999 to 2009. Fifteen AEDs were categorized into first and second generation of AEDs. Continuous use of AEDs was defined as at least 2 consecutive AED prescriptions totaling more than a 30-day supply. Polytherapy was defined as 2 or more AEDs continuously used for at least 30 overlapping days. Annual prevalence was estimated and compared.

Results:

We included 2,099 pregnant women who were enrolled in Florida Medicaid from 1999 to 2009 and exposed to AEDs during pregnancy. Although there were fluctuations, overall AED use in the study cohort did not increase from 2000 to 2009 (β ± standard error [SE]: −0.07 ± 0.06, p = 0.31). The use of first-generation AEDs decreased (β ± SE: −6.21 ± 0.47, p < 0.0001), whereas the use of second-generation AEDs increased (β ± SE: 6.27 ± 0.52, p < 0.0001) from 2000 to 2009. AED use in polytherapy did not change through the study period. Valproate use reduced from 23% to 8% in the study population (β ± SE: −1.61 ± 0.36, p = 0.0019), but this decrease was only for women receiving an AED for epilepsy and was not present for other indications.

Conclusion:

The second-generation AEDs are replacing first-generation AEDs in both monotherapy and polytherapy. Valproate use has declined for epilepsy but not other indications. Additional changes in AED use are expected in future years.

Previous studies reported a 2- to 3-fold increase in the malformations among offspring with in utero exposure to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs).1–3 The risks have been reported as 3.1% to 9.0% for major congenital malformations (MCMs), 37% for one minor abnormality (MA), and 11% for 2 MAs in offspring with in utero exposure to AEDs.2,4 Several studies found that AED polytherapy poses a higher risk of malformation (8.6%) than that of AED monotherapy (4.5%).4–6

The risk of MCMs increases to 4% to 9% after in utero exposure to the first-generation AEDs.5,7 The percentage of MCMs was reported as 6.5% for phenobarbital,8 3.7% for phenytoin,9 and 2.2% for carbamazepine.10 Valproate has shown a greater risk (6.2%–20.3%) of MCM,9,11–13 which is 7.3-fold higher than that of nonexposed, and 4-fold higher than in those exposed to other AEDs.12 It has been noted that in utero exposure to valproate was associated with elevated risk of impaired cognitive function for children at 3 years of age,14 and reduced cognitive abilities in multiple domains for children at 6 years old.15 These cognitive deficits can occur without MCMs or MAs. For the second-generation AEDs, the risks of MCMs have been reported as 2.0% to 3.7% for lamotrigine,16–18 0.7% to 2.4% for levetiracetam,18,19 2.8% for oxcarbazepine,20 and 4.2% to 4.8% for topiramate.18,20

Despite the aforementioned concerns of MCMs in AED use, current literature lacks comprehensive, population-based information on AED use trends over time in pregnant women. The aim of this study was to examine the pattern of AED use in pregnant women enrolled in Florida Medicaid.

METHODS

Data sources.

This study is based on 2 statewide, retrospective, 10-year data sources: Florida Medicaid claims and Florida Birth Vital Statistics from January 1, 1999, to December 31, 2009. Two datasets were linked using the mother's social security number and the child's date of birth.

Florida Birth Vital Statistics at Florida Department of Health collects and manages a statewide birth certificate dataset. Birth time, place, and date for infants, and demographic characteristics for infant, mother, and father are recorded on the birth certificates.

Florida Medicaid covers pregnant women up to 185% federal poverty level.21 Florida Medicaid claims, assembled by Florida's Agency for Health Care Administration, provide monthly details on Medicaid eligibility and medical and pharmacy claims for Florida Medicaid fee-for-service beneficiaries. Medical claims from inpatient hospital, outpatient clinics, or emergency rooms include diagnosis codes (ICD-9-CM), procedure codes (up to 31 Current Procedural Terminology codes), source of admission, physician type, discharge status, and total amount of charges. Pharmacy claims include National Drug Codes (NDCs) for all dispensed drugs reimbursed by Medicaid. In this study, maternal exposure to study drugs was determined using NDCs from pharmacy claim records, and mother's indications diagnosed during pregnancy were identified using diagnosis codes from medical claims. The operational definitions for all demographic and clinical characteristics are described in table e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Florida and the Florida Department of Health.

Study population.

This study included female Florida Medicaid enrollees who were older than 15 years, took AEDs during pregnancy, delivered a live infant between April 1, 2000, and December 31, 2009, and were enrolled in the Medicaid program as identified by pregnancy status. The study cohort of maternal-baby pairs was generated by linking the Florida Medicaid claims and Florida Birth Vital Statistics.

Exclusion criteria for maternal-infant pairs included mothers with dual eligibility for Medicare, HMO (health maintenance organization), or other private insurance.

Study design.

This was a retrospective cohort study. The study index date was the infant's birth date. The AED exposure window was defined as the 9-month pregnancy period after the first day of the last menstrual date. The study period covered January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2009.

Assessment of AED exposure.

In this study, exposure to AEDs was determined from Medicaid pharmacy claims using NDCs. AEDs were classified as a group of drugs, including the first-generation AEDs: carbamazepine, ethosuximide, phenobarbital, phenytoin, primidone, and valproate; and the second-generation AEDs: felbamate, gabapentin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, pregabalin, tiagabine, topiramate, and zonisamide. Pharmacy claims in Medicaid data have been approved as an accurate source for the assessment of drug exposure.22 The rates of concordance with patient self-reported medication use was high in previous studies.22,23

Information of drug use from Medicaid pharmacy claims included NDC for filled prescription drugs and the number of days for which the drug was supplied.24 As previously mentioned, the birth anomalies are related to dose and time of exposure during pregnancy, MCM associates with teratogen exposure in the first trimester, and MA and low birth weight relate to maternal drug exposure in the third trimester.25 Maternal drug exposure during the entire pregnancy period can affect the combined outcome. The exposure window was thus established as the period of 14 days before the first day of the mother's last menstrual period to the infant's birth date. The drug exposure was defined as any one dose of study drug dispensed during the exposure window, including drugs dispensed before the exposure window with days of supply covering at least 1 day of the exposure window. Adding 14 days before the pregnancy is to account for the conception period and the residual effects of AEDs. Sensitivity study was conducted to examine the effects of different drug exposure windows on the combined outcome.

The mother's last menstrual period was obtained using a multistep algorithm derived from linkages to the healthy start prenatal screen, which contains more accurate information because it is collected during the first trimester of the pregnancy.26 When healthy start information was not available, the last menstrual period date on the birth certificate was used. If these 2 dates were not available (about 13% of last menstrual period date is missing on birth certificates), this information was imputed from clinical estimate.27–29 A previous study suggested that the last menstrual period from birth certificates and clinical estimates agreed within less than 2 weeks.30

Continuous use of AEDs was defined as at least 2 consecutive prescriptions for AEDs or totaling more than a 30-day supply. Polytherapy was defined as one or more other AEDs continuously used for at least 30 overlapping days. Annual prevalence was estimated and compared across different drug combinations, including the first- and second-generation AEDs.

Assessment of characteristics of study participants.

Demographic characteristics were identified from birth certificates,31 whereas comorbidities or comedications during pregnancy were identified using ICD-9-CM or NDCs from Medicaid medical claims.32 The operational definitions for all covariates adjusted in data analysis are described in table e-1. The secular trend of AED use was assessed in the overall study cohort, as well as the specific subgroups, such as patients with epilepsy and patients with psychiatric disorder only, defined as bipolar, anxiety, depression, or mental disorder.

Statistical analysis.

SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for data analyses and modeling, and SigmaPlot 11.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA) or Microsoft PowerPoint 2010 14.0 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) was used for graphs. The secular trend was analyzed using Joinpoint Regression Program version 3.4.3 (National Cancer Institute, Silver Spring, MD).

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the secular trend of AED use from January 2000, the start of the drug exposure period, and the end of the drug exposure period in December 2009. The univariate linear regression slope β and corresponding standard error (SE) were estimated and tested under H0: β = 0. Significance level for all tests was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 753,377 pregnant women were identified in the Florida Medicaid program between 2000 and 2009. The final study cohort included 2,099 women exposed to AEDs during pregnancy (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants

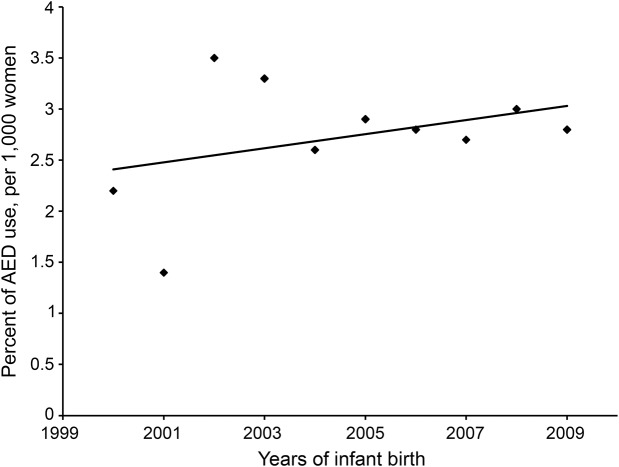

The percentage of mothers with any AED use during pregnancy over all pregnant women enrolled in Florida Medicaid was calculated for each study year. The secular trends of AED use in the study population from 2000 to 2009 were analyzed and plotted in figure 1. Of the total 753,377 mothers in the Florida Medicaid program, AED exposure in mothers during pregnancy ranged from 1.4 to 3.5 per 1,000 women from the year 2000 to 2009. Despite the observed small fluctuations, AED use in pregnant women enrolled in Florida Medicaid was stabilized from 2000 to 2009 (β ± SE: −0.07 ± 0.06, p = 0.31).

Figure 1. Percentage of AED use in pregnant women in Florida Medicaid.

β = 0.07, SE = 0.06, p = 0.31. AED = antiepileptic drug.

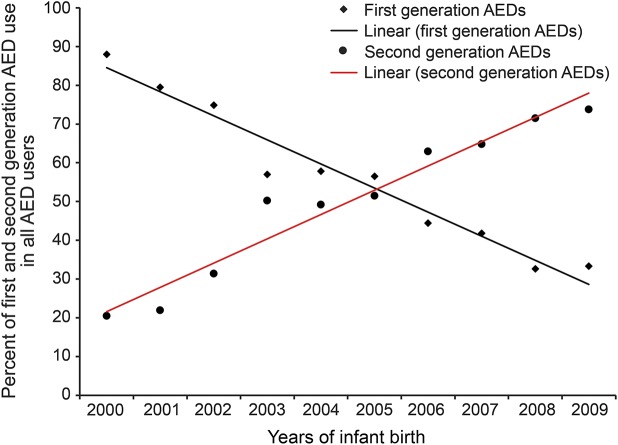

AED exposure was further categorized into 2 groups: first- and second-generation AEDs. As shown in figure 2, the number of pregnant women exposed to first-generation AEDs decreased significantly from 2000 to 2009 (β ± SE: −6.11 ± 0.47, p < 0.0001), and the overall exposure to second-generation AEDs increased (β ± SE: 6.27 ± 0.52, p < 0.0001).

Figure 2. Percentage of first- and second-generation AED use from 2000 to 2009.

β = −6.21, SE = 0.47, p < 0.0001 for first-generation AED use; β = 6.27, SE = 0.52, p < 0.0001 for second-generation AED use. AED = antiepileptic drug.

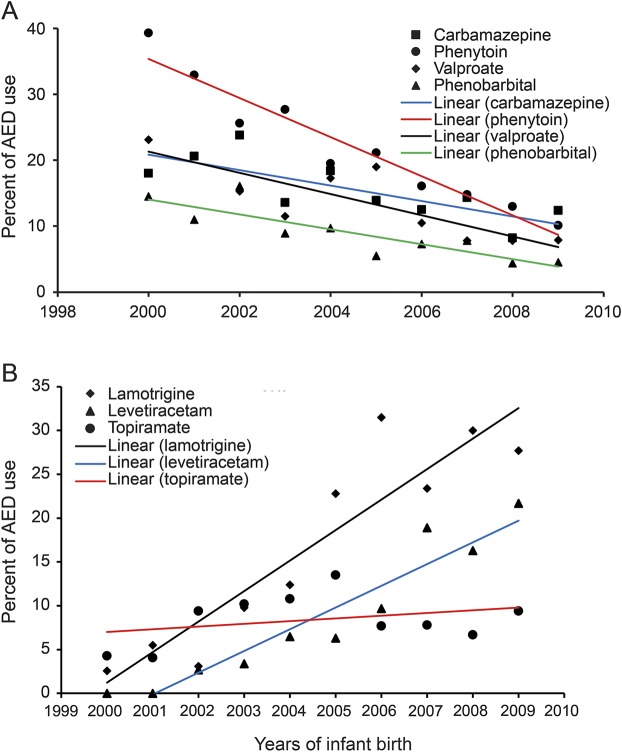

Figure 3, A and B, delineates the secular trends for the most frequently used AEDs in the study population. The dispensing rates of 4 of the most frequently used first-generation AEDs significantly decreased from 2000 to 2009. The use of valproate decreased more slowly than phenytoin (β ± SE: −1.61 ± 0.36 vs −2.97 ± 0.29), but faster than carbamazepine (β ± SE: −1.61 ± 0.36 vs −1.17 ± 0.34) and phenobarbital (β ± SE: −1.61 ± 0.36 vs −1.13 ± 0.24) (figure 3A). As shown in figure 3B, lamotrigine (2.6% in 2000, 30% in 2008, β ± SE: 3.48 ± 0.51, p = 0.0001) and levetiracetam (0% in 2001, 21.7% in 2009, β ± SE: 2.48 ± 0.28, p < 0.0001) are 2 frequently used second-generation AEDs that rapidly increased during the study period. Another frequently used second-generation AED, topiramate, did not significantly change in rate of use through the study period (4.3% in 2000 to 9.4% in 2009; β ± SE: 0.31 ± 0.97, p = 0.36).

Figure 3. Percentage of most frequently used first- and second-generation AEDs.

(A) First-generation AEDs from 2000 to 2009: β = −1.17, SE = 0.34, p = 0.009 for carbamazepine use; β = −2.97, SE = 0.29, p < 0.0001 for phenytoin use; β = −1.61, SE = 0.36, p = 0.0019 for valproate use; and β = −1.13, SE = 0.24, p = 0.0015 for phenobarbital use. (B) Second-generation AEDs from 2000 to 2009: β = 3.48, SE = 0.51, p = 0.0001 for lamotrigine use; β = 2.48, SE = 0.28, p < 0.0001 for levetiracetam use; and β = 0.31, SE = 0.97, p = 0.36 for topiramate use. AED = antiepileptic drug.

Of a total of 2,099 pregnant women exposed to AEDs, more than half were exposed to 2 or more AEDs during pregnancy. The secular trends for AED use in polytherapy or monotherapy did not significantly vary over time (polytherapy was 62% in 2000 and 63% in 2009, β ± SE: 0.35 ± 0.90, p = 0.71). In subgroup analysis, we found that overall AED use did not significantly change either in the patients with epilepsy (β ± SE: 0.28 ± 0.87, p = 0.75) or the patients with psychiatric disorders only (β ± SE: 0.95 ± 0.71, p = 0.22).

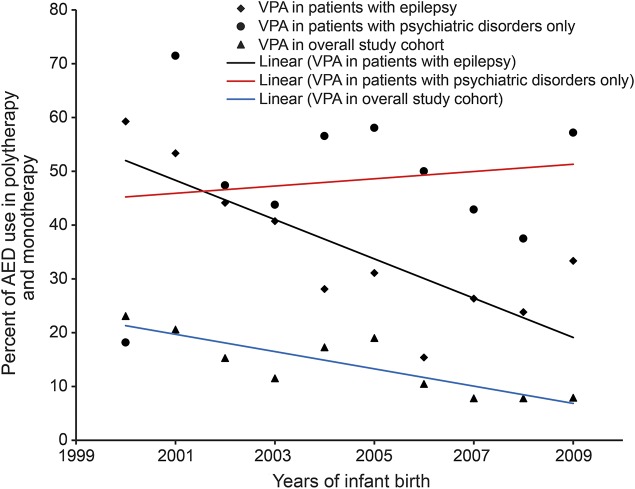

Given that valproate has been shown to produce the highest risks of malformations and neurodevelopment, specific analyses by indication were conducted. In figure 4, we present the rates of valproate use in the overall study cohort, patients with epilepsy, and patients with psychiatric disorders only. There were significant reductions of valproate use in the overall study cohort (β = −1.61, SE = 0.36, p = 0.002) and patients with epilepsy (β = −3.65, SE = 0.95, p = 0.005). However, valproate use was not reduced in patients with psychiatric disorders only (β = 0.67, SE = 1.66, p = 0.70).

Figure 4. Percentage of valproate use in overall study cohort or patients with different indications.

β = −1.61, SE = 0.36, p = 0.002 for VPA use in overall study cohort; β = −3.65, SE = 0.95, p = 0.005 for VPA use in patients with epilepsy; β = 0.67, SE = 1.66, p = 0.70 for VPA use in patients with psychiatric disorders only. AED = antiepileptic drug; VPA = valproate.

We further investigated folate use in the study population. Folate use was identified using the NDC for vitamin or active ingredient of folic acid. Of a total of 2,099 pregnant women exposed to AEDs during pregnancy, we identified 1,610 women (77%) who had taken folate before or during pregnancy. There was no significant change in folate use from 2000 to 2009 (β = 0.08, SE = 0.39, p = 0.83).

DISCUSSION

We investigated the trends of AED use in a cohort of pregnant women in the Florida Medicaid program. Specifically, we examined the secular trends of AED exposure during pregnancy overall as well as in polytherapy and monotherapy.

The results noted in table 1 delineate a profile of the study population. Epilepsy, anxiety, bipolar, depression, migraine, and other mental disorders are common indications for the women exposed to AEDs during pregnancy. In addition, mothers exposed to AEDs during pregnancy were more likely to be unmarried (65% vs 48%) and fewer were of black race (17% vs 23%) compared to the general population of pregnant women with a live birth listed in Florida Medicaid.33 Figure 1 shows the prevalence of AED use in pregnant women enrolled in Florida Medicaid from 2000 to 2009. AED use was not significantly changed from 2000 to 2009 in the overall study cohort, patients with epilepsy, or patients with psychiatric disorders only. Approximately 0.14% to 0.35% of pregnant women in our study were exposed to AEDs during this time period, which may be slightly lower than what was documented in the general population, 0.2% to 0.5%.21,34 Of all prescribed AEDs, the use of polytherapy had no significant reduction from 2000 to 2009 in our study. The percentage of pregnant women with epilepsy receiving polytherapy in our cohort is higher than that of other cohorts.35 A previous study regarding prescribing patterns of AEDs in the United States from 2001 to 2007 concluded that increased AED use in pregnant women was driven by a 5-fold increase in the use of second-generation AEDs.36 Although overall AED use did not increase significantly in our cohort, we did see an increase in use of second-generation AEDs and a reduction of first-generation AEDs during pregnancy.

In our study cohort, carbamazepine, phenytoin, and valproate were the 3 most frequently used AEDs in pregnant women from 2002 to 2004. In 2005, lamotrigine replaced carbamazepine as the most frequently used AED. In 2007, levetiracetam surpassed valproate and became the most frequently used AED next to lamotrigine. Thus, our results showed that the top 2 most frequently used AEDs after 2007 were lamotrigine and levetiracetam, which is similar to the results previously reported from a survey of epilepsy centers.37

It is noted in this study that valproate use decreased significantly from 2000 to 2009 in pregnant women across all treatments. The patterns are coincident with previous studies for AED exposure in women with epilepsy of childbearing age in Florida Medicaid and the North American Epilepsy Registry.37,38 Given that several studies during the time period of our study have reported an association of fetal valproate exposure with an increased risk of MCMs and with impairment in children's cognitive function, it is not surprising that valproate use has declined in pregnant women who use AEDs during pregnancy.12,39 However, when analyzed by indications, valproate use decreased for epilepsy indications, but not for nonepilepsy indications, such as bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, and mental disorders. It seems that neurologists treating epilepsy are more aware or responsive to valproate's teratogenic risks than those treating nonepilepsy indications, which are primarily psychiatric.

Our study population is limited to pregnant women enrolled in the Medicaid program, which comprises persons of lower socioeconomic status than that of the general population or among private insurance holders. Our study spans 10 years, from 2000 to 2009, with more information about secular trends of AED prescribing in pregnant women. Analyses of the secular trends were conducted to disclose the details about the change of AED prescribing patterns over time in pregnant women. The overall insignificant change of AED use appears to be attributable to the rapid increase in use of newer generation AEDs compensating for the reduction of first-generation AEDs. New scientific findings or Food and Drug Administration (FDA) black box warnings on the safety issues of AEDs influence the prescribing patterns of AEDs as well. Given that the FDA issued a black box warning for topiramate related to congenital malformations,40 and that new data continue to be collected, we expect to see changes in AED use in pregnant women in future years.

Several limitations should be considered as a consequence of using linked claim data and the nature of the study design. First, this study is based on 2 linked data sources. Unmatched data because of poor quality or missing identifiers were not analyzed. The study population is limited to matched mother-infant pairs with mothers enrolled in the Florida Medicaid program. Therefore, sample size and power are restricted because of relatively rare outcomes and exposures.

Second, Medicaid claim data were used for reimbursement of health care providers. Pharmacy claims only show dispensed prescriptions, thus actual drug use in patients might differ because of drug incompliance and over-the-counter drug use.

Third, AED exposure was defined as any AED use during the overall pregnancy period. Given that a large number of women enrolled in the Medicaid program after they were pregnant, the AED exposure window and length cannot be identified.

Fourth, although birth certificates and medical claims are key data sources for medical epidemiologic research, there are limitations in their validity and reliability.31,32

Our study identified the trends for AED use during pregnancy from 2000 to 2009. Use of second-generation AEDs has increased in pregnant women, while use of first-generation AEDs has declined. Use of the AED with the highest teratogenic risk, valproate, has declined in patients with epilepsy but not in patients using it for other indications. Additional changes in AED use are expected in future years as more information is obtained on relative risks.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- AED

antiepileptic drug

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- MA

minor abnormality

- MCM

major congenital malformation

- NDC

National Drug Code

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Xuerong Wen: drafting/revising the manuscript for content, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, acquisition of data, statistical analysis. Dr. Kimford Meador: drafting/revising the manuscript for content, study concept or design, interpretation of data, obtaining funding. Dr. Abraham Hartzema: drafting/revising the manuscript for content, study concept or design, and interpretation of data.

STUDY FUNDING

This work was supported in part by grant U01 NS038455 (Meador).

DISCLOSURE

X. Wen reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. K. Meador serves on the editorial boards of Neurology®, Behavior & Neurology, Epilepsy & Behavior, Epilepsy.com, and the Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology and on the professional advisory board for the Epilepsy Foundation; he has received travel support from Sanofi-Aventis, and received research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Eisai Inc., Marinus Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Myriad Genetics, Inc., NeuroPace, Inc., Pfizer, SAM Technology Inc., UCB Pharma, the NIH National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (2RO1-NS38455 [PI], 2U01-NS038455 [multi-PI], 1 R01 NS076665 [consultant]), the PCORI (PCORI 527 [co-PI]), and the Epilepsy Foundation. Dr. Meador has consulted for the Epilepsy Study Consortium, which receives money from multiple pharmaceutical companies (in relation to his work for Eisai, NeuroPace, Novartis, Supernus, Upsher-Smith Laboratories, UCB Pharma, and Vivus Pharmaceuticals). The funds for consulting for the Epilepsy Study Consortium were paid to his university. A. Hartzema has a consultant appointment with Pfizer not related to this study. He also has a senior advisor appointment to the FDA CDRH, and declares that the views expressed here are his personal views and not those of the FDA. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Samren EB, van Duijn CM, Christianens GC, et al. Antiepileptic drug regimens and major congenital abnormalities in the offspring. Ann Neurol 1999;46:739–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaneko S, Kondo T. Antiepileptic agents and birth defects: incidence, mechanisms and prevention. CNS Drugs 1995;3:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomson T. Which drug for the pregnant woman with epilepsy? N Engl J Med 2009;360:1667–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaneko S, Otani K, Fukushima Y, et al. Teratogenicity of antiepileptic drugs: analysis of possible risk factors. Epilepsia 1988;29:459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friis ML. Facial clefts and congenital heart defects in children of parents with epilepsy: genetic and environmental etiologic factors. Acta Neurol Scand 1989;79:433–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomson T, Battino D, French J, et al. Antiepileptic drug exposure and major congenital malformations: the role of pregnancy registries. Epilepsy Behav 2007;11:277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pennell PB. Antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy: what is known and which AEDs seem to be safest? Epilepsia 2008;49(suppl 9):43–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes LB, Wyszynski DF, Lieberman E. The AED (antiepileptic drug) pregnancy registry: a 6-year experience. Arch Neurol 2004;61:673–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jentink J, Loane MA, Dolk H, et al. Valproic acid monotherapy in pregnancy and major congenital malformations. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2185–2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrow J, Russell A, Guthrie E, et al. Malformation risks of antiepileptic drugs in pregnancy: a prospective study from the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:193–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Finnell RH, et al. In utero antiepileptic drug exposure: fetal death and malformations. Neurology 2006;67:407–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyszynski DF, Nambisan M, Surve T, Alsdorf RM, Smith CR, Holmes LB. Increased rate of major malformations in offspring exposed to valproate during pregnancy. Neurology 2005;64:961–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meador KJ, Pennell PB, Harden CL, et al. ; for the HOPE Work Group. Pregnancy registries in epilepsy: a consensus statement on health outcomes. Neurology 2008;71:1109–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. ; for the NEAD Study Group. Cognitive function at 3 years of age after fetal exposure to antiepileptic drugs. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1597–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. ; for the NEAD Study Group. Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure and cognitive outcomes at age 6 years (NEAD study): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:244–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al. ; EURAP Study Group. Dose-dependent risk of malformations with antiepileptic drugs: an analysis of data from the EURAP epilepsy and pregnancy registry. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:609–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell E, Kennedy F, Russell A, et al. Malformation risks of antiepileptic drug monotherapies in pregnancy: updated results from the UK and Ireland Epilepsy and Pregnancy Registers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:1029–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernández-Díaz S, Smith CR, Shen A, et al. ; North American AED Pregnancy Registry. Comparative safety of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. Neurology 2012;78:1692–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mawhinney E, Craig J, Morrow J, et al. Levetiracetam in pregnancy: results from the UK and Ireland Epilepsy and Pregnancy Registers. Neurology 2013;80:400–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Hviid A. Newer-generation antiepileptic drugs and the risk of major birth defects. JAMA 2011;305:1996–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Florida Department of Children and Families. Family-related Medicaid programs fact sheet. Available at: http://www.dcf.state.fl.us/programs/access/docs/fammedfactsheet.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2014.

- 22.Ray WA, Griffin MR. Use of Medicaid data for pharmacoepidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 1989;129:837–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.West SL, Savitz DA, Koch G, Strom BL, Guess HA, Hartzema A. Recall accuracy for prescription medications: self-report compared with database information. Am J Epidemiol 1995;142:1103–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper WO, Hernandez-Diaz S, Arbogast PG, et al. Major congenital malformations after first-trimester exposure to ACE inhibitors. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2443–2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costei AM, Kozer E, Ho T, Ito S, Koren G. Perinatal outcome following third trimester exposure to paroxetine. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156:1129–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simmons M, Thompson D, Graham C. An evaluation of the healthy start prenatal screen. Available at: http://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/childrens-health/healthy-start/healthy-start-docs/prenatal-screen-eval.pdf. Accessed December 13, 2012.

- 27.Eworuke E, Hampp C, Saidi A, Winterstein AG. An algorithm to identify preterm infants in administrative claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21:640–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raebel MA, Ellis JL, Andrade SE. Evaluation of gestational age and admission date assumptions used to determine prenatal drug exposure from administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005;14:829–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrade SE, Gurwitz JH, Davis RL, et al. Prescription drug use in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:398–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearl M, Wier ML, Kharrazi M. Assessing the quality of last menstrual period date on California birth records. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2007;21(suppl 2):50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Northam S, Knapp TR. The reliability and validity of birth certificates. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2006;35:3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salemi JL, Tanner JP, Block S, et al. The relative contribution of data sources to a birth defects registry utilizing passive multisource ascertainment methods: does a smaller birth defects case ascertainment net lead to overall or disproportionate loss? J Registry Manag 2011;38:30–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Florida Department of Health. Live Births: Vital Statistics Annual and Provisional Reports, 2009. Available at: http://www.flpublichealth.com/VSBOOK/pdf/2009/Births.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wide K, Winbladh B, Kallen B. Major malformations in infants exposed to antiepileptic drugs in utero, with emphasis on carbamazepine and valproic acid: a nation-wide, population-based register study. Acta Paediatr 2004;93:174–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Battino D, Tomson T, Bonizzoni E, et al. ; EURAP Study Group. Seizure control and treatment changes in pregnancy: observations from the EURAP Epilepsy Pregnancy Registry. Epilepsia 2013;54:1621–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bobo WV, Davis RL, Toh S, et al. Trends in the use of antiepileptic drugs among pregnant women in the US, 2001–2007: a medication exposure in pregnancy risk evaluation program study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2012;26:578–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meador KM, Penovich P, Baker GA, et al. ; for the NEAD Study Group. Antiepileptic drug use in women of childbearing age. Epilepsy Behav 2009;15:339–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wen X, Meador KJ, Winterstein AG, Hartzema AG. Utilization of antiepileptic drugs in Florida Medicaid women with epilepsy of childbearing age. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21(suppl 3):322. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harden CL, Meador KJ, Pennell PB, et al. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy—focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): teratogenesis and perinatal outcomes. Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology 2009;50:1237–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: risk of oral clefts in children born to mothers taking Topamax (topiramate). Available at: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/ucm245085.htm. Accessed March 16, 2014.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.