Summary

Serotonergic neurons modulate behavioral and physiological responses from aggression and anxiety to breathing and thermoregulation. Disorders involving serotonin (5HT) dysregulation are commensurately heterogeneous and numerous. We hypothesized that this breadth in functionality derives in part from a developmentally determined substructure of distinct subtypes of 5HT neurons each specialized to modulate specific behaviors. We find, by manipulating developmentally defined subgroups one-by-one chemogenetically, that the Egr2-Pet1 subgroup is specialized to drive increased ventilation in response to carbon dioxide elevation and acidosis. Further, this subtype exhibits intrinsic chemosensitivity and modality-specific projections – increasing firing during hypercapnic acidosis and selectively projecting to respiratory chemosensory but not motor centers, respectively. These findings show that serotonergic regulation of the respiratory chemoreflex is mediated by a specialized molecular subtype of 5HT neuron harboring unique physiological, biophysical, and hodological properties specified developmentally, and demonstrate that the serotonergic system contains specialized modules contributing to its collective functional breadth.

Introduction

Serotonin (5HT), a monoamine neurotransmitter synthesized in the brain and gut, is involved in many neurological and psychiatric disorders, and plays central, even life-sustaining, roles in controlling respiration, heart rate, and body temperature (Gingrich and Hen, 2001; Hilaire et al., 2010; Hodges and Richerson, 2010; Jacobs and Azmitia, 1992; Ray et al., 2011). Such a multiplicity of jobs underlies the unwanted effects often elicited upon deliberate therapeutic alteration of 5HT levels pharmacologically. Life threatening cardiorespiratory dysfunction and hyperthermia can ensue, as can debilitative conditions involving depression, anxiety, anhedonia, bowel dysfunction, and diminished libido (Boyer and Shannon, 2005; Ferguson, 2001). Therapeutic strategies better tailored to specific aspects of 5HT-regulated physiology and behavior are needed. Advances would come through knowledge of serotonergic neuronal organization, including identification of specialized subtypes of 5HT neurons, the behaviors they regulate, and potential differentially expressed druggable substrates.

Molecular differences across brain serotonergic neurons and across serotonergic progenitor cells are indeed being uncovered (Gaspar and Lillesaar, 2012; Jensen et al., 2008; Wylie et al., 2010), and at least some of these gene expression differences may point to intrinsic functional differences, and thus the possibility of identifiable, highly specialized subtypes of 5HT neurons. We recently developed genetic tools to test this prediction, now permitting linkage between a specific molecular subtype of 5HT neuron and function at the cellular, circuit, and organismal level. Applying these tools here, we sought to identify if such functional modularity exists within and can be deconstructed from the 5HT neuronal system in mice.

We applied, for the first time, the intersectional feature of our recently engineered chemogenetic silencing allele, RC::FPDi (Ray et al., 2011), to target inhibitory DREADD receptor (hM4Di (Armbruster et al., 2007)) expression to the major molecularly and developmentally defined subtypes of 5HT neurons (Jensen et al., 2008), one subtype at a time, for in vivo activity modulation and subtype-specific functional probing in the awake mouse. Specifically, we queried each subtype for a role in regulating the respiratory chemoreflex. This reflex is responsible for increasing breathing in response to tissue CO2 elevation (hypercapnia) and acidosis to restore these vital chemistries back within a normal range (Dean and Nattie, 2010; Guyenet et al., 2010; Nattie and Li, 2012), and it is dependent in part on serotonergic activity, as we revealed upon acute suppression of the 5HT neuronal system en masse (Ray et al., 2011) and as suggested in rodent genetic models of embryonic 5HT neuron loss or dysfunction constitutively across the entire system (Hodges et al., 2008). Here, we asked if the activity of a specific 5HT neuron subtype is necessary for a normal hypercapnic ventilatory response, and if so, does it exhibit specialized biophysical and hodological properties.

Targeting Di expression to a specific subtype of 5HT neuron was achieved by partnering the RC::FPDi allele with a 5HT neuron-specific Flpe recombinase driver, here Pet1::Flpe (Jensen et al., 2008), and a Cre driver, which in overlap with Pet1::Flpe resolves a particular 5HT neuron subtype. Using this in vivo approach, we discovered that the Egr2-Pet1 5HT neuron subtype mediates control of this breathing reflex. Further, we found that hypercapnic acidosis triggers Egr2-Pet1 neurons to increase their rate of firing, a biophysical feature referred to as chemosensitivity. By contrast, other 5HT neuron subtypes residing adjacently in the same tissue microenvironment, but originating from a distinct progenitor cell domain embryologically, failed to exhibit chemosensitivity. Axonal projections were also found to be specialized for the Egr2-Pet1 5HT neuron subtype, specifically interfacing with brainstem regions involved in the chemosensory but not primary motor control of breathing; the latter task appears served by a distinct developmental class of 5HT neurons. Thus, a previously unappreciated functional modularity comprises the brain 5HT neuronal system and is employed in the dynamic control of breathing. It derives, at least in part, developmentally and even incorporates sensory and motor subdivisions. Decoding this modularity not only informs on the organizational logic of this clinically important neuronal system, but also opens up the potential for discovery of tailored circuit- and function-specific therapeutic leads, for example here as relates to disorders of respiratory homeostasis.

Results

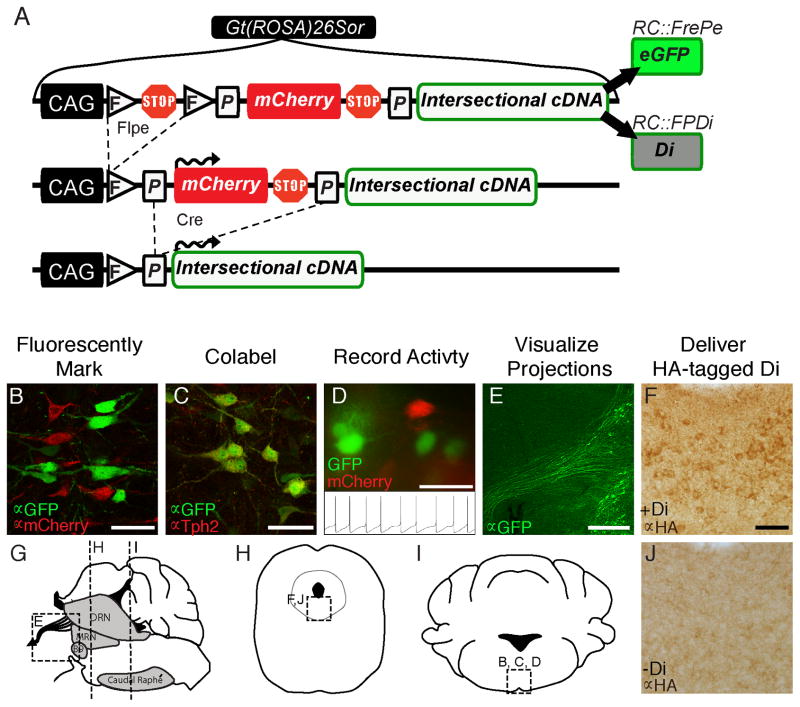

Targeting discrete subtypes of 5HT neurons for manipulation in vivo

To study different subtypes of 5HT neurons in vivo, we applied two different dual-recombinase based intersectional alleles: one for cell- and axonal projection marking, called RC::FrePe (Bang et al., 2012); and the other, RC::FPDi (Ray et al., 2011), used intersectionally here for the first time, for hyperpolarization and activity manipulation (Figure 1A). Both alleles are identical in design except that in RC::FPDi, the synthetic inhibitory receptor Di (Armbruster et al., 2007) is expressed solely in the dual Cre/Flpe-targeted subtype of 5HT neuron, versus eGFP for RC::FrePe. Both are configured so that mCherry marks remainder 5HT neurons. Di, the Gi/o protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) with engineered selectivity for the synthetic ligand clozapine-N-oxide (CNO), triggers cell-autonomous hyperpolarization and diminished neuron excitability via coupling with the K+ channel Kir in response to CNO binding (Armbruster et al., 2007), as we have demonstrated previously for 5HT neurons in general (Ray et al., 2011). Di activation has also been shown to inhibit synaptic transmission (Stachniak et al., 2014). Here we employed the dual recombinase (Cre and Flpe)-feature of RC::FPDi to target Di expression, and thus the capacity for CNO-triggered neuronal inhibition, to distinct subtypes of 5HT neurons. This set of transgenics – the two intersectional alleles RC::FPDi and RC::FrePe, the serotonergic-specific Pet1::Flpe driver (Jensen et al., 2008), and Cre-drivers whose individual expression domains overlap with distinct subpopulations within the serotonergic population – provide a novel toolbox allowing for highly specific functional (physiological, biophysical, hodological, and molecular) and anatomical probing of subsets of 5HT neurons (Figure 1B–J).

Figure 1. Intersectional alleles RC::FrePe and RC::FPDi for labeling and activity manipulation of subtypes of 5HT neurons.

(A) Gt(ROSA)26Sor knock-in alleles RC::FrePe and RC::FPDi offer fluorescent labeling and inducible Di-mediated manipulation of neuron subtypes, respectively, when partnered intersectionally with Flp- and Cre-encoding transgenes. (B) 5HT neurons fluorescently marked with eGFP or mCherry from RC::FrePe, detected via indirect immunofluorescence. (C) Co-immunodetection of serotonergic marker Tph2 and GFP expressed in 5HT neurons using RC::Fe (a Flp-only responsive derivative of RC::FrePe in which the loxP-mCherry-stop-cassette has been removed) partnered with Pet1::Flpe. (D) Endogenous eGFP or mCherry fluorescence in live 5HT neurons in a 200 μm slice suitable for patch-clamp recording (inset - action potentials recorded from fluorescently labeled 5HT neuron). (E) Indirect immunofluorescent detection of eGFP-labeled projections (Pet1::Flpe, RC::Fe tissue) forming the median-forebrain bundle (schematized in G). Scale bar is 300 μm. (F) HA-tag immunodetection of Di in somata of 5HT neurons using derivative allele RC::FDi (Flpe-responsive) partnered with Pet1::Flpe, as compared to J, control single transgenic RC::FDi (no Flpe, thus not expressing Di) sibling tissue. Scale bar is 50 μm in B–D, F and J. (H–I) Schematic coronal sections indicating location of panels B, C, D, F, and J. Abbreviations: DRN – dorsal raphé nucleus, MRN – median raphé nucleus. See also Figure S1.

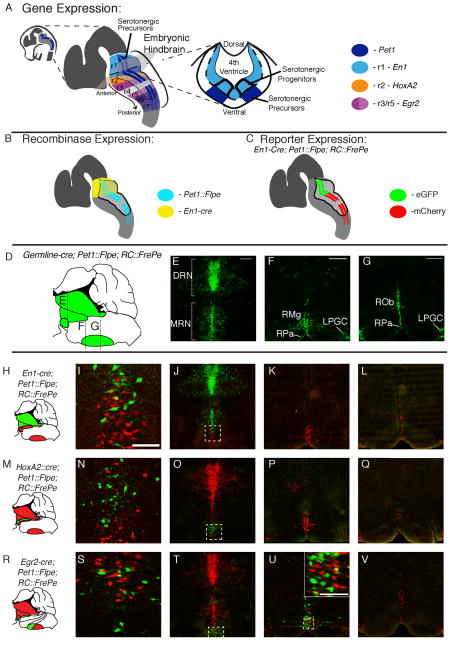

Major molecular and developmental subtypes of 5HT neurons (Jensen et al., 2008) were examined by partnering intersectional allele RC::FPDi or RC::FrePe (Figure 1A) with the pan-serotonergic lineage driver, Pet1::Flpe, and a Cre driver expressed developmentally in a specific rhombomere overlapping with a distinct subset of serotonergic progenitors (Figure 2A–C). The En1-cre knock-in allele (En1Cki (Kimmel et al., 2000)), when used in this intersectional paradigm, resulted in Di (if using RC::FPDi) or eGFP (if using RC::FrePe) expression specifically in all rhombomere (r) 1-derived 5HT neurons (Figure 2A–C), which in the adult brainstem comprise anatomically the entire dorsal raphé nucleus (DRN, also referred to as B4, B6, and B7 nuclei) as well as part of the median raphé nucleus (MRN or B5, B8, and B9 nuclei) (Figure 2H–L). The HoxA2::cre transgenic (also referred to as rhombomere specific enhancer 2, Rse2::cre (Awatramani et al., 2003)) used intersectionally resulted in Di or eGFP expression in r2-derived 5HT neurons, which distribute within the MRN (Figure 2M–Q). The Egr2-cre knock-in allele (Egr2tm2(cre)Pch also referred to as Krox-20cre (Voiculescu et al., 2000)) resulted in Di or eGFP in r3- and r5-derived 5HT neurons, which distribute within the MRN (the r3-derived constituent) (Figure 2R–T) and the raphé magnus (RMg or B3, the r5-derived constituent) (Figure 2R, U). Note, 5HT neurons do not appear to derive from r4 (previously established (Pattyn et al., 2003)), and the most caudal 5HT neurons, marked by mCherry (Figure 2U, V), derive embryonically from r6/7 and have yet to be accessed in a subtype-specific manner for Di expression due to present lack of a suitably selective Cre-driver.

Figure 2. Molecular and developmental subtypes of 5HT neurons accessed by intersectional genetics.

(A) The embryonic hindbrain is segmented along the anterior-posterior (AP) axis into rhombomeres (r1–r7), each expressing distinct genes; En1 expressed in r1 (light blue), HoxA2 in r2 (orange), and Egr2 in r3 and r5 (dark and light pink, respectively). Serotonergic progenitors are situated ventral in the hindbrain ventricular zone and span the AP axis of the developing hindbrain, giving rise to post-mitotic 5HT precursor cells that express Pet1 (Hendricks et al., 1999) (dark blue) in all but r4. (B) Recombinase driver lines use gene enhancer/promoter elements to express Flpe and cre in specific domains, for example En1-cre (yellow) in r1 and Pet1::Flpe (cyan) in 5HT precursors. (C) Pairing recombinase drivers En1-cre and Pet1::Flpe with RC::FrePe (see Figure 1A) switches on eGFP in r1-derived 5HT precursors and mCherry in all other 5HT precursors. (D–G) The entire Pet1::Flpe expressing 5HT neuron population is labeled with eGFP upon pairing with RC::Fe. (D) Sagittal brainstem schematic shows approximate rostrocaudal levels of E, F, and G. (H–V) Adult fate-mapped 5HT neurons labeled with eGFP or mCherry in triple transgenics. (J, O, T) DRN and MRN showing the intersectional subtype of 5HT neuron labeled with eGFP+ (green), and remaining 5HT neurons with mCherry (red); detection by indirect immunofluorescence. Higher magnification of boxed regions in I, N, S. (K, P, U) Raphé magnus (RMg) and rostral raphé pallidus (RPa). (L, Q, V) Raphé obscurus (Rob), caudal RPa and lateral paragigantocellularis (LPGC). Scale bars is 300 μm in E, F, G and applies to all images in a column. Scale bar is 100 μm in I and inset of U.

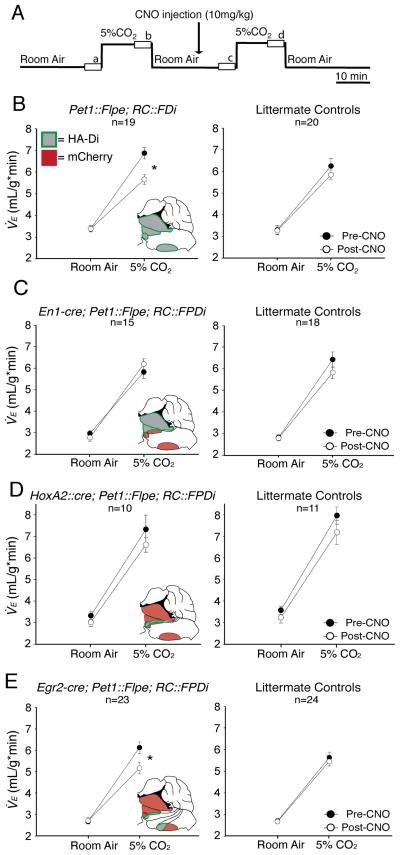

The Egr2-Pet1 5HT neuron subtype is necessary for mounting a normal respiratory CO2 chemoreflex

To provide a reference level of respiratory suppression against which to compare ventilatory outcome following silencing of the different subtypes of 5HT neurons, we included a cohort of mice in which Di was expressed in all Pet1::Flpe-expressing 5HT neurons to silence the system en masse. To do this, we applied a double (rather than triple) transgenic strategy using Pet1::Flpe with the derivative allele RC::FDi, which depends only on Flpe activity for Di expression (this Flpe-only-dependent target allele was generated by removal of the floxed cassette in RC::FPDi by germline Cre activity, and as such, is otherwise identical to RC::FPDi). Like the fluorescent cell marking observed across the extent of the raphé system of Pet1::Flpe neurons (Figure 2E–G), we immunodetected Di, via its HA-tag, in cells throughout the serotonergic raphé in Pet1::Flpe, RC::FDi tissue (Figure 1F and Figure S1). In addition to cell bodies, Di is also expected to localize substantially to axon terminals (Stachniak et al., 2014).

To assess effects of CNO/Di-mediated neuron silencing on the ventilatory response to hypercapnia, mice were assayed by whole body plethysmography in room air (0% CO2) and in 5% CO2, before and then after CNO injection (10mg/kg intraperitoneally, Figure 3A: a, b, c, and d, respectively). In this design, each animal served as its own control – an important feature given the expected animal-to-animal variation in absolute ventilation values reported by others using these kinds of assays (Hodges et al., 2002; Strohl et al., 1997). Experimental (Di-expressing) cohorts included: double transgenic Pet1::Flpe, RC::FDi mice, enabling inhibition of Pet1::Flpe 5HT neurons en masse upon CNO administration; triple transgenic En1-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FPDi mice, to suppress r1-derived (En1-Pet1) 5HT neurons; triple transgenic HoxA2::cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FPDi mice, to suppress r2-derived (HoxA2-Pet1) 5HT neurons; and triple transgenic Egr2-cre; Pet1::Flpe, RC::FPDi mice, to suppress r3/r5-derived (Egr2-Pet1) 5HT neurons. In addition to within-animal comparisons, we also phenotyped non-Di-expressing littermate controls for each of the four experimental genotypes, and found that the typical increase in ventilation in response to the increase in arterial PCO2 levels during 5% CO2 conditions was seen in all experimental genotypes and littermate controls before CNO injection. Using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA, we assessed the effects of CNO administration (pre- versus post-CNO injection as one factor) on minute ventilation (V̇E) in room air and in 5% CO2 (inspired gas as the other factor) in each cohort of mice. A significant interaction (p<0.001) of CNO-administration with the V̇E response to 5% CO2 was found in two genotypes only: the Pet1::Flpe, RC::FDi mice (en masse manipulation), as expected, and the Egr2-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FPDi mice (manipulation of r3/r5-derived 5HT neurons only).

Figure 3. Egr2-Pet1 5HT neurons specialize in regulating breathing in response to tissue CO2 elevation and acidosis in mice.

(A) Paradigm for plethysmographic assessment at 34 C of respiratory responses to 5% inspired CO2 during quiet wakefulness in the daytime before and during CNO application (10mg/kg i.p. injection); boxes (a, b, c, d) represent stretches analyzed from continuous recordings. (B) Pet1::Flpe; RC::FDi mice (left panel) show reduced minute ventilation (V̇E) responses to 5% CO2 during as compared to before CNO administration (significant interaction between 5% CO2 and CNO, p < 0.001), contrasting littermate controls (right panel) which have indistinguishable V̇E responses to 5% CO2 under either CNO conditions. V̇E responses to 5% CO2 in triple transgenics En1-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FPDi (C, left panel) and HoxA2::cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FPDi (D, left panel) and littermate controls (right panels) are indistinguishable in the presence or absence of CNO. Triple transgenic Egr2-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FPDi mice (E, right panel) showed reduced V̇E responses to 5% CO2 upon CNO administration as compared to pre-CNO baselines (significant interaction between 5% CO2 and CNO, p < 0.001); littermate controls (right panel) showed no change post-CNO. Data shown as mean ± s.e.m. and statistically analyzed using 2-way RM ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc analysis. Brainstem schematics show the 5HT neuron subtype (green outline) expressing Di (gray) and remaining mCherry-expressing 5HT neurons (red).

To illustrate this blunting of the hypercapnic ventilatory response, we plotted in Figure 3 the average V̇E in room air and in 5% CO2 for each cohort pre- and post-CNO. Notably, littermate controls had normal ventilatory responses to 5% CO2 both before and during CNO treatment, indicating that CNO alone (without Di) is neutral to this assay readout, consistent with its reported bioneutrality in mice (Armbruster et al., 2007; Guettier et al., 2009). Further, the ventilatory response of littermate control mice, En1-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FPDi mice, and HoxA2::cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FPDi mice to the first versus second CO2 challenge were indistinguishable (even in the presence of CNO), importantly ruling out any order-of-presentation effect associated with the serial nature of the 5% CO2 challenge. Collectively, these findings identify Egr2-Pet1 5HT neurons as necessary for mounting a normal respiratory CO2 chemoreflex.

Finding significant reduction in the hypercapnic ventilatory response after CNO administration in triple transgenic Egr2-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FPDi mice as well as in the reference en masse silenced Pet1::Flpe, RC::FDi mice, we calculated a “difference value” as a within-animal measure of the extent to which the V̇E response to 5% CO2 (the percent increase) was reduced upon CNO/Di-induced neuronal inhibition. Specifically, the following was calculated for each animal and averaged for a given cohort: [(V̇E5%CO2/V̇ERoom Air)*100% − 100%]pre-CNO − [(V̇E5%CO2/V̇ERoom Air)*100% − 100%]post-CNO. Strikingly, both Pet1::Flpe, RC::FDi and Egr2-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FPDi cohorts each exhibited a blunted “difference value” of ~36%; two-way repeated measures ANOVA on the percent increase in ventilation with CNO and genotype as factors yielded a p value of 0.949, suggesting that these two groups are indistinguishable with respect to degree of ventilatory response blunting upon CNO/Di-mediated neuronal silencing.

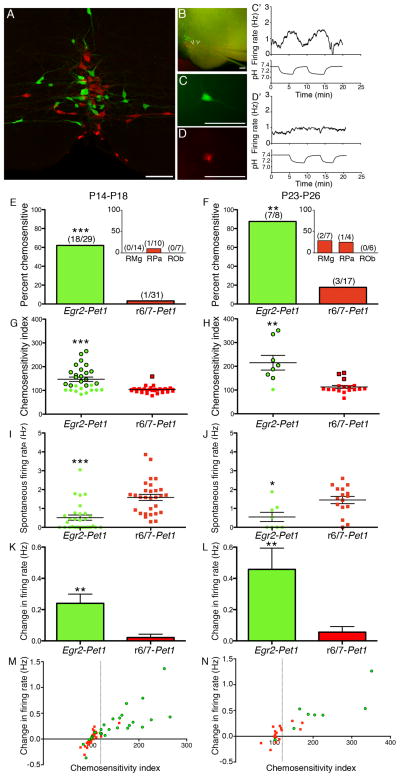

Egr2-Pet1 neurons are sensitive responders electrophysiologically to small changes in CO2/pH

Finding that Egr2-Pet1 neurons regulate breathing in response to inspired 5% CO2, we next explored whether these neurons were CO2 chemosensitive by electrophysiological measure – increasing action potential firing in response to physiologically relevant decreases in pH. Previous findings point to a portion of medullary 5HT neurons as being chemosensitive, as revealed either by patch clamp recording from labeled 5HT neurons cultured from mice (Ray et al., 2011), or from unlabeled mouse or rat raphé neurons in slice or culture assayed post hoc, in some cases, for serotonergic identity (Wang and Richerson, 1999; Wang et al., 2001). Here we used acute medullary slices from Egr2-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FrePe mice to record from eGFP-labeled Egr2-Pet1 neurons as well as other medullary 5HT neurons, i.e. the r6/7-Pet1 subtype labeled with mCherry (Figure 2U, V and 4A). Action potentials and pH were simultaneously monitored while slices were superfused with aCSF containing blockers of ionotropic glutamate and GABA receptors (APV, CNQX, and picrotoxin) bubbled with 5% CO2, resulting in a pH of 7.4. While recording, superfusate was switched to 9% CO2, causing a pH decrease to ~7.15 (Figure 4C′–D′). We considered the neuron to be chemosensitive if: changes in spike frequency inversely paralleled changes in pH reproducibly over two 9% CO2 challenges (four pH shifts), the time course of the change was consistent, and the firing rate relative to baseline per 0.2 pH units (chemosensitivity index, CI) was 120% or greater, as per criteria established previously (Wang and Richerson, 1999; Wang et al., 2001). Not all 5HT neurons were spontaneously active under these standard recording conditions, therefore after determining a neuron’s spontaneous firing rate, a constant depolarizing current was injected to increase the firing rate to an average ‘adjusted baseline’ of ~0.6 Hz, after which conditions of hypercapnic acidosis were induced, and from which chemosensitive indices were calculated. Bringing in line the firing rate of each 5HT neuron in this way before the hypercapnic challenge removed the potential confound of seemingly large chemosensitivity indices for neurons with especially low baseline firing rates (Wang et al., 2001).

Figure 4. Cellular chemosensitivity to hypercapnic acidosis maps to the Egr2-Pet1 subtype of 5HT neuron.

(A) Egr2-Pet1 (green) and r6/7-Pet1 (red) subtypes of 5HT neurons intersperse within the RMg, as revealed by eGFP and mCherry detection in brainstem sections from Egr2-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FrePe mice. (B) Live Egr2-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FrePe brainstem slice showing eGFP and mCherry fluorescence suitable for neuron subtype identification prior to patch-clamp recording. Right arrowhead, eGFP-labeled Egr2-Pet1 neuron, shown at higher magnification in C, and its firing rate in relation to pH (C′), indicating chemosensitivity. Left arrowhead, mCherry-labeled r6/7-Pet1 neuron, shown again in D, and its firing rate in relation to pH (D′), indicating lack of chemosensitivity under these conditions. Scale bars are 100 μm. (E–F) Percent chemosensitive neurons of each subtype recorded from Egr2-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FrePe slices ages P14–P18 (E) or P23–P26 (F). Number of chemosensitive neurons over total neurons recorded of that subtype shown in parentheses over each bar. ***P<0.0001, **P<0.002 (Fisher’s Exact Test). Insets show anatomical breakdown of neurons from the r6/7-Pet1 subtype; note, all Egr2-Pet1 neurons reside within the RMg. (G–H) Chemosensitivity index of neurons recorded at P14–P18 (Egr2-Pet1 n=29, r6/7-Pet1 n=31, ***P<0.0001) and P23–P26 (Egr2-Pet1 n=8, r6/7-Pet1 n=17, **P=0.0002). Data points for neurons that fit the criteria of chemosensitive outlined in black. (I–J) Spontaneous firing rates (no current injection) of neurons at P14–P18 (Egr2-Pet1 n=29, r6/7-Pet1 n=29, ***P<0.0001), and P23–P26 (Egr2-Pet1 n=8, r6/7-Pet1 n=16, *P = 0.0107). (K–L) Average change in firing rate measured over pH shifts, **P=0.0005 at P14–18 and **P=0.0009 at P23–25. Two-tailed unpaired t-test was used for statistical analysis in (G–L); error bars show mean ± s.e.m. (M–N) Average change in firing rate versus chemosensitivity index. Dotted line demarcates chemosensitivity index of 120. P<0.0001 at P14–18 and P23–25 (Pearson correlation).

We assayed eGFP+ (Egr2-Pet1) and mCherry+ (r6/7-Pet1) neurons in medullary slices spanning rostrocaudally from the RMg (B3) through the raphé obscurus (ROb, also referred to as B2) and raphé pallidus (RPa or B1) from triple transgenic Egr2-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FrePe pups fourteen- to eighteen-postnatal days old (P14–P18). We found that ~62% (18/29) of the Egr2-Pet1 medullary 5HT neurons were chemosensitive (Figure 3E) and had an average CI of 174.3% ± 10.3%. Average CI among all sampled neurons of this subtype (both chemosensitive and not) was 147.0% ± 9.2% (Figure 4G). This is in contrast to 1 of 31 r6/7-Pet1 medullary 5HT neurons (~3%) exhibiting chemosensitivity. This single r6/7-Pet1 neuron had a CI of 158.7%, whereas the average CI of all sampled r6/7-Pet1 neurons was 103.2 ± 2.5 (Figure 4E, G). We analyzed brainstem slices from more mature P23–P26 triple transgenics, motivated by reports that, in rat, the proportion of chemosensitive neurons in the medullary raphé increases with age (Wang and Richerson, 1999). At P23–P26, ~86% of Egr2-Pet1 neurons were found chemosensitive (Figure 4F) with an average CI of 231.3% ± 30.4%, significantly greater than at P14–P18 (P=0.03, unpaired t-test). Average CI of all sampled P23–P26 Egr2-Pet1 neurons was 215.1% ± 30.86% (Figure 4H). Among r6/7-Pet1 5HT neurons at this age, 3 of 17 (~18 %) were chemosensitive with an average CI of 162.0% ± 13.7%. Average CI of all r6/7-Pet1 5HT neurons sampled at this age was 113.0% ± 6.5% (Figure 4H). Thus, across postnatal developmental stages, CO2 chemosensitivity among medullary 5HT neurons maps to the Egr2-Pet1 subtype.

Prior to testing neurons for chemosensitivity, we measured spontaneous firing rate (no current injection). Unexpectedly, we found that among all medullary 5HT neurons assayed, low spontaneous firing rate predicted chemosensitivity even with chemosensitivity calculated from a current-injected normalized baseline in those neurons with very low firing rate (Spearman correlation P<0.0001 for P14–18 data and P=0.0205 for P23–26 data). Indeed, we observed that Egr2-Pet1 5HT neurons had lower frequency spontaneous firing or no spontaneous firing (Figure 4I, J), contrasting that observed for the r6/7-Pet1 5HT neurons. To rule out a bias towards preferentially classifying neurons with lower baseline firing rates as chemosensitive based on chemosensitivity index, we also examined average change in firing rate across pH shifts (Figure 4K,L), finding significantly higher firing rate changes among Egr2-Pet1 5HT neurons. Further, average change in firing rate significantly correlated with chemosensitivity index (Figure 4M, N).

Thus, Egr2-Pet1 5HT neurons with embryological origin from r5 are functionally distinct from the mCherry+ r6/7-derived 5HT neurons, even though they reside adjacently intermingled within the same anatomical nucleus (e.g. RMg, Figure 4A). So functional subtypes of 5HT neurons, at least in some cases, do not conform to anatomically defined groupings per se but rather to developmental molecular expression.

Egr2-Pet1 neurons project to brainstem regions involved in chemosensory processing but not respiratory motor nuclei

Finding that Egr2-Pet1 neurons are chemosensitive in slice preparations (Figure 4) and that their activity is necessary for mice to mount normal ventilatory responses to hypercapnia (Figure 3), we set out to identify brainstem regions receiving projections from Egr2-Pet1 neurons. Resolving Egr2-Pet1 axons from those of other 5HT neurons was enabled by the RC::FrePe allele, which when partnered with Pet1::Flpe and Egr2-cre, drives eGFP expression solely in Egr2-Pet1 neurons at levels sufficient to label axons as well as somata (Figure 1B, E). Here we used this approach to explore Egr2-Pet1 5HT neuron projections to brainstem respiratory centers. To provide a maximal eGFP+ projection reference for Pet1::Flpe-expressing 5HT neurons en masse, we mapped eGFP-labeled projections to brainstem respiratory nuclei using driver Pet1::Flpe partnered with the Flpe-only-dependent eGFP reporter, RC::Fe, the derivative allele of RC::FrePe and thus the most suitable comparator (Figure 2E–G). eGFP-labeled projections from Pet1::Flpe, RC::Fe mice were found in all major respiratory brainstem regions (Figure 5A–E, K, L, and Figure 6A–C, G).

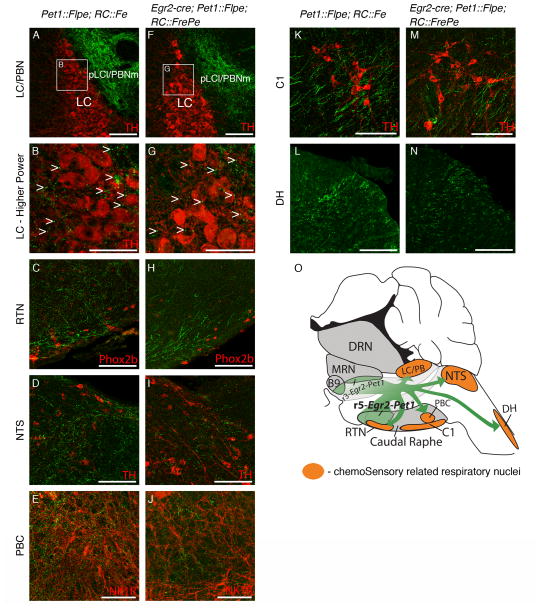

Figure 5. Egr2-Pet1 5HT neurons project to respiratory nuclei implicated in PCO2/pH sensory signal transduction and integration.

Representative (at least 3 mice of each genotype examined) confocal images of axonal projections (eGFP+, green, detected by indirect immunofluorescence) from either all Pet1::Flpe-expressing neurons (Pet1::Flpe, RC::Fe mice A–E, K, L) or from Egr2-Pet1 neurons (Egr2-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FrePe mice F–J, M, N). Brainstem nuclei (indirect immunofluorescence detection of cell identity markers in red) implicated in the processing of sensory input related to PCO2/pH levels: (A, F) Locus coeruleus (LC) neuron cell bodies visualized via immunodetection of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), under conditions which highlight soma as opposed to dendrites. Note that pericoerulear regions, such as the lateral pLC (pLCl) shown here, also referred to as the parabrachial nucleus medial (PBNm), harbor extensive dendrites from LC neurons and are significant sites for synaptic input to LC neurons; (B, G) Higher magnification view of the areas boxed in A and F, respectively. Arrowheads highlight examples of puncta from eGFP-labeled processes. (C, H) Retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN), identified via Phox2b immunodetection coupled with anatomical location; (D, I) Nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), TH; (E, J) PreBötzinger complex (PBC), neurokinin1 receptor; (K, M) the C1 nucleus, TH; and (L, N) the spinal dorsal horn (DH). (O) Hindbrain schematic depicting 5HT raphé (gray) and Egr2-Pet1 region (green), among brainstem/spinal cord regions examined for projections (orange). Scale bars are 100 μm in all images except B, G where scale bar is 50 μm.

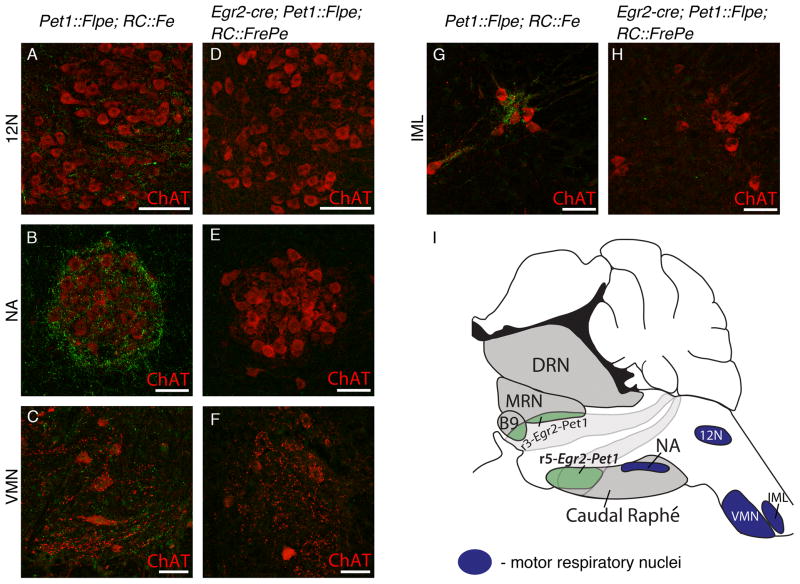

Figure 6. Egr2-Pet1 5HT neurons do not project to primary respiratory motor nuclei.

Representative (at least 3 mice of each genotype were examined) confocal images of axonal projections (eGFP+, green, detected by indirect immunofluorescence) from either all Pet1::Flpe-expressing neurons, (Pet1::Flpe, RC::Fe) A–C, G, or from Egr2-Pet1 neurons, (Egr2-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FrePe) D–F, H. Brainstem motor nuclei involved in respiratory motor output: (A,D) the hypoglossal nucleus (12N) stained for choline acetyltransferase (ChAT); (B, E) the nucleus ambiguus (NA), ChAT; and (C, F) the ventral spinal motor neurons (VMN); ChAT. (G, H) Projections to the intermediolateral cell column of the spinal cord (IML), ChAT. (I) Hindbrain schematic depicting 5HT raphé (gray) and Egr2-Pet1 region (green), among the brainstem/spinal cord nuclei examined for projections (dark blue). Scale bars are 100 μm in A and D, and 50 μm in B, C and E–H.

Of these brainstem nuclei involved in respiratory control and which receive 5HT projections, only some were found to receive projections from the Egr2-Pet1 class of 5HT neurons (Figure 5). Notably, this target set of nuclei share the feature of processing and/or detection of chemosensory information (Nattie and Li, 2012). We detected Egr2-Pet1 eGFP+ axons in the locus coeruleus and pericoerulear/parabrachial region (a region harboring locus coeruleus neuron dendrites (Shipley et al., 1996; Van Bockstaele et al., 1999)) which plays an important role in hypercapnic arousal (Gargaglioni et al., 2010; Kaur et al., 2013), the glutamatergic Phox2b-expressing neurons of the chemosensitive retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN) (Wang et al., 2013), the solitary tract nucleus (NTS) which is a key integration site of peripheral chemosensory information (Dean and Putnam, 2010), and the preBötzinger complex, with its role in integration of chemoreceptor inputs as well as respiratory rhythm generation (Feldman et al., 2013) (Figure 5F–J). Additionally, we detected eGFP+ axons in the C1 nucleus, also involved in the integration of chemosensory information, and the spinal cord dorsal horn, which may integrate respiratory, thermal, and pain sensory pathways (Lu and Perl, 2007) (Figure 5M, N). We did not detect Egr2-Pet1 eGFP+ axons in primary motor nuclei, such as the hypoglossal nucleus, the nucleus ambiguus, and spinal cord ventral horn motor neurons (Figure 6D–F), even though these nuclei receive eGFP+ projections from 5HT neurons labeled en masse (Figure 6A–C). These primary motor respiratory nuclei must receive projections from a different 5HT neuron class, such as the r6/7-Pet1 subtype.

Discussion

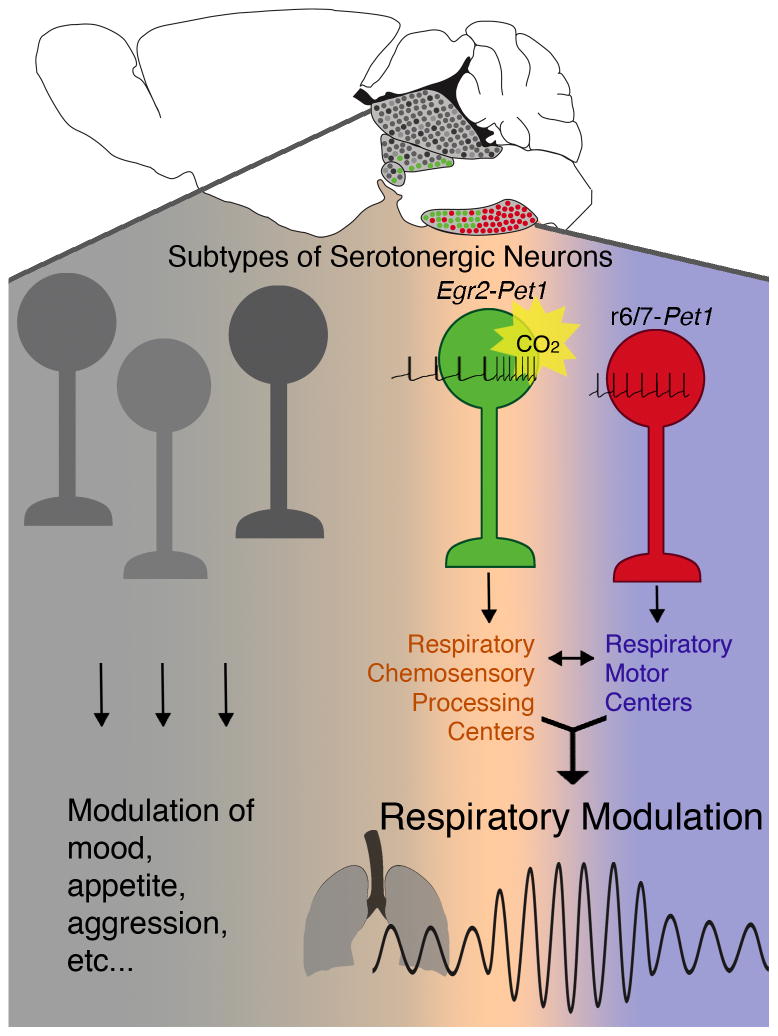

Here we report discovery of function-specific 5HT neuron modules, defined by physiological outcome, cellular biophysical properties, and axonal projections. Further, we show that these functional differences map onto developmental cell lineage – the originating rhombomere (r) and gene-expression code of the parental progenitor cell – rather than anatomical grouping of the mature neuron by itself. Specifically, we show that the Egr2-Pet1 neuron subtype is necessary for the full hypercapnic ventilatory response in awake mice (Figure 3), is specialized among medullary 5HT neurons in its excitatory response electrophysiologically to small milieu changes in PCO2/pH (Figure 4), and projects axons specifically to respiratory brainstem nuclei involved in chemosensory but not motor processing (Figure 5, 6), indicating a modality- as well as function-specific role in the regulation of breathing (Figure 7). By contrast, the r6/7-Pet1 neurons, deriving from a separate rhombomere and molecular code than Egr2-Pet1 neurons but which ultimately reside interspersed, lack this chemosensitivity (Figure 4). Moreover, by anatomical subtraction, the r6/7-Pet1 neuron subtype likely projects to motor respiratory nuclei – a conclusion also supported by earlier (non-molecular) tract-tracing studies (Hilaire et al., 2010; Holtman, 1988; Holtman et al., 1990; VanderHorst and Ulfhake, 2006; Voss et al., 1990). Together, these data support a model in which 5HT neuron modules exist within the 5HT neuronal system, that some major functional divisions within the 5HT neuronal system are genetically specified early in gestation, and that the overall breadth in processes modulated by this system reflects, at least in part, a summation of numerous composite activities mediated by distinct specialized subsets of 5HT neurons.

Figure 7. The Egr2-Pet1 subtype of 5HT neuron is specialized to modulate the respiratory CO2 chemoreflex via selective projections to respiratory chemosensory processing centers and the ability to sense and transduce PCO2/pH changes.

Sagittal brain schematic of serotonergic raphé with the Egr2-Pet1 subtype shown in green, the r6/7-Pet1 subtype in red, and other 5HT subtypes in shades of gray. Inventory of Supplemental Information

The capability to independently query distinct molecularly-defined subsets of 5HT neurons for functional specificity in vivo, as performed in this study, was enabled by intersectional genetics; in particular, by a set of intersectional transgenes for directing Di or eGFP expression solely to cells having expressed both Cre and Flpe recombinases. As engineered here, this translated into the first-time ability to inducibly manipulate and study the different major developmental (rhombomere-derived) subtypes of 5HT neurons. Using this approach, we found that acute (CNO/Di-triggered) suppression of neuronal activity in Egr2-Pet1 5HT neurons, but not other Pet1::Flpe 5HT neurons, blunts the hypercapnic ventilatory reflex, and furthermore, does so to a roughly similar extent as that observed upon suppression of all Pet1 neurons en masse. This suggests that Egr2-Pet1 neurons are principal serotonergic contributors to the respiratory chemoreflex and suggests that not all 5HT neurons play a measurable role in this process.

Intersectional genetics also discriminated each 5HT neuron subtype fluorescently in brainstem slices, allowing for electrophysiological characterization of each genetically defined subtype under various conditions. We found that the majority of Egr2-Pet1 neurons increased action potential firing in response to hypercapnic acidosis, even the modest challenge of a 0.2 pH unit drop. This responsiveness to small pH changes was not observed in the other major medullary 5HT neuron subtype, the r6/7-Pet1 subtype, even those r6/7-Pet1 neurons that reside immediately adjacent to and presumably share the same microenvironment as Egr2-Pet1 neurons (Figure 4A). Thus, while microenvironment and/or circuit activity may shape certain neuronal properties, medullary 5HT neuron chemosensitivity appears specified more fundamentally, at the level of developmental cell lineage arising from the Egr2/r5 serotonergic progenitor population. Curiously, chemosensitive glutamatergic Phox2b-expressing neurons in the RTN (Wang et al., 2013) also derive from r5 and experience a history of Egr2 expression (Dubreuil et al., 2009; Ray et al., 2013). It will be important to explore more deeply the extent of molecular and mechanistic features shared between Egr2-Pet1 5HT neurons and RTN Phox2b neurons.

This ability of Egr2-Pet1 5HT neurons to increase firing in response to small pH changes suggests they may function at the frontline of the chemoreflex in vivo, perhaps acting with other chemosensitive neurons such as RTN neurons (Guyenet et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013), to translate life-threatening milieu PCO2/pH changes into electrical changes capable of altering central respiratory drive. In turn, ventilation would be altered, affecting arterial and tissue PCO2, which would shift the extracellular bicarbonate acid-base equilibrium to restore pH to within normal range.

A small subset of rostral raphé neurons in midbrain slices (harboring DRN and MRN areas) have been reported as responding to pH changes (Baccini et al., 2012; Severson et al., 2003). In our in vivo chemoreflex assay (Figure 3), though, we see no effect on the hypercapnic (5% CO2) ventilatory response following acute CNO/Di-mediated perturbation of En1-Pet1 (DRN neurons) or HoxA2-Pet1 (MRN) 5HT neurons (Figure 3), but rather only upon silencing all Pet1::Flpe neurons or just the Egr2-Pet1 neurons. It is possible these En1-Pet1 and HoxA2-Pet1 subsets of rostral 5HT neurons may be important for CO2-mediated arousal rather than the respiratory chemoreflex (Buchanan and Richerson, 2010).

Deserving mention are studies (Depuy et al., 2011; Mulkey et al., 2004) that have argued against medullary 5HT neuron chemosensitivity and involvement in the respiratory chemoreflex; our findings help resolve this controversy. These earlier negative studies are in fact fully consistent with the data presented here because they focused on either ROb (Depuy et al., 2011) or parapyramidal (Mulkey et al., 2004) 5HT neurons, neurons that we now know are r6/7-Pet1 neurons and for which we too failed to reveal chemosensitivity. Instead, chemosensitivity maps to the Egr2-Pet1 5HT neuron subtype, which resides largely within the RMg. In accord with this are recent recordings from unanesthetized perfused decerebrate rat brainstem preparations that also highlight chemosensitive 5HT neurons in the RMg (Iceman et al., 2013).

In mapping eGFP+ projections to brainstem respiratory centers from Egr2-Pet1 neurons versus other 5HT neuron subtypes, we uncovered a surprising dichotomy. Egr2-Pet1 axons project to respiratory nuclei involved in chemosensory processing but not motor output. The latter receive projections from other 5HT neuron subtype(s), most likely r6/7-Pet1 5HT neurons. Thus, PCO2/pH-induced excitation of Egr2-Pet1 5HT neurons appears modality-specific, likely directly influencing a chemosensory-related neural network but not primary motor outputs.

We propose that serotonergic projections to primary motor respiratory nuclei stem largely from the r6/7-Pet1 neuron subtype. Classical tract-tracing results show that the hypoglossal nucleus and the nucleus ambiguous receive serotonergic input predominantly from caudal ROb and RPa 5HT neurons (Depuy et al., 2011; Ptak et al., 2009; VanderHorst and Ulfhake, 2006), which we show are of the r6/7-Pet1 lineage (Figure 2). Further, these ROb and RPa 5HT neurons – i.e. r6/7-Pet1 neurons identified here – have been implicated in long term facilitation at phrenic and hypoglossal motor nuclei (Ling et al., 2001; Lovett-Barr et al., 2006; Mitchell and Johnson, 2003) and have been proposed to modulate motor activity more generally (Jacobs and Fornal, 1997). These findings support our observation of a sensory versus motor divide in respiratory modulation by 5HT neurons, with the r6/7-Pet1 neurons influencing respiratory motor output and Egr2-Pet1 neurons influencing chemosensory input and processing (Figure 7). Indeed, a new model for central respiratory control is suggested where chemosensory information is first integrated by a brainstem network and then relayed to respiratory motor centers.

As part of this model, it is possible that Egr2-Pet1 neurons, through their selective projections to chemosensory respiratory nuclei, influence the ventilatory response to hypercapnia in part by providing tonic excitatory drive to these downstream centers. Upon loss or suppression of this tonic drive, for example through CNO/Di-mediated inhibition of Egr2-Pet1 neurons, the ventilatory response to hypercapnia could become blunted.

The discovery of distinct sensory and motor subdivisions within the serotonergic system not only reshapes our thinking about 5HT system organization, but also resolves a controversy wherein 5HT neurons have been proposed to have a primary role in the modulation of motor function rather than sensory processing (Jacobs and Fornal, 1997). The data presented here suggests that this view is correct only when limiting analyses to particular subtypes of 5HT neurons; it does not apply, for example, to the Egr2-Pet1 5HT neuron subtype. Further, this distinction in modality appears specified developmentally.

Collectively, these data define the 5HT neural system as highly patterned, with neuron subtypes exhibiting unique cellular, electrophysiological, hodological, and molecular properties, which underpin specific and separable physiological processes and modalities. The data reveal major functional divisions within the 5HT system that appear specified early in development. Finer functional subdivisions are expected, and their delineation comprises important next steps. Resolving this neural system – neuron subtype-by-subtype, function-by-function, expressed gene-by-gene, as begun here – offers the possibility of explaining clinical differences among 5HT disorders, for example, some manifesting homeostatic dysfunction and others mood dysregulation. A particular genetic alteration or environmental insult may affect the functional capacity of one 5HT neuron subtype but not others. This work also provides a discovery platform for disorder-specific therapeutic leads and/or diagnostic biomarkers. These particular findings on respiratory control offer a precise 5HT neuron subtype and associated circuits from which to discover more specific substrates with clinical potential precisely for disorders involving respiratory homeostasis such as the sudden infant death syndrome, Rett syndrome, serotonin syndrome, and sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (Garcia Iii et al., 2013; Hilaire et al., 2010; Paterson et al., 2006; Richerson and Buchanan, 2011; Toward et al., 2013).

Experimental Procedures

Transgenic Mouse Lines

Procedures were in accord with IACUC policies at Harvard Medical School and the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth. Triple transgenics were generated by breeding Pet1::Flpe, RC::FrePe (Bang et al., 2012; Jensen et al., 2008) or Pet1::Flpe, RC::FPDi (Ray et al., 2011) mice to En1-cre (En1Cki (Kimmel et al., 2000)), HoxA2::cre (Rse::cre (Awatramani et al., 2003)), or Egr2-cre (Egr2Cki (Voiculescu et al., 2000)) mice. Double and single-transgenic littermates served as controls. For pan-5HT marking or manipulation, RC::FrePe and RC::FPDi were bred to Tg(ACTB-cre)2Mrt mice to remove the loxP-flanked cassette, generating RC::Fe (Flp-dependent eGFP) and RC::FDi (Flp-dependent Di) mice, which were bred to Pet1::Flpe hemizygous mice to generate double transgenics and single-transgenic controls.

Immunohistochemistry

Anesthetized mice were transcardially perfused with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Brains and spinal cords were soak fixed in 4% PFA at 4°C overnight (for RC::FrePe tissue) or 2 hours (for RC::FPDi tissue). Tissue was cryoprotected in 30% sucrose/PBS for 48 hours at 4°C before freezing in TFM and storage at −80°C. Tissue was cryosectioned (40 μm) and processed as floating sections.

For fluorescent staining, sections were washed with PBS and PBS with 0.1% Triton-X-100 (PBS-T), blocked with 5% normal donkey serum in PBS-T for 1 hour at room temperature (RT), and incubated with primary antibody at 4°C for 24–72 hours: Chicken-anti-GFP (Abcam ab13970-100, 1:5000), rabbit-anti-DsRed (Clontech 632496, 1:3000), goat-anti-Phox2b (Santa Cruz sc-13224, 1:500), rabbit-anti-Tyrosine Hydroxylase (Millipore ab152, 1:5000), rabbit-anti-NK1R (Sigma S8305, 1:5000), or goat-anti-Choline Acetyltransferase (Millipore, AB144P, 1:500). Primary antibody binding was detected via fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibody (JacksonImmuno): 488 donkey-anti-chicken, Cy3 donkey-anti-rabbit, or Cy3 donkey-anti-goat. Sections were mounted onto slides, coverslipped, and imaged using a Zeiss Axioplan (5x objective) or a Zeiss LSM confocal (25x objective). Tiled z-stacks were processed as maximum intensity projections and background subtraction performed identically across all images using NIH Image J software (Schneider et al., 2012).

For colorimetric DAB detection of Di, sections were washed with PBS, bleached in 0.3% H2O2 for 30 minutes, washed with PBS-T, blocked with 5% normal goat serum for 1 hour at RT, and incubated with rabbit-anti-HA primary antibody (Invitrogen 71-5500, 1:200) for 72 hours at 4°C. Primary antibody was detected using Vectastain Elite DAB (Vectorlabs, PK-6100): tissue was incubated for 30 minutes at RT with biotin-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit antibody, washed, and avidin-biotin complexing reagents applied for 30 minutes. Staining was developed with 1mg/ml DAB (3, 3′-diaminobenzidine, Sigma). Sections were mounted to slides, dehydrated in ethanol, cleared with xylene, coverslipped, and imaged.

Whole Animal Plethysmography

Unanesthetized double transgenic Pet1::Flpe, RC::FDi mice, as well as triple transgenic En1-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FPDi mice; HoxA2::cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FPDi mice; Egr2-cre, Pet1::Flpe, RC::FPDi mice; and respective littermate controls were individually acclimated for 20 minutes in a plethysmograph chamber filled with room air gas, then 5% CO2 for 15 minutes, then switched back to room air for 15 minutes. Mice were removed for an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 10mg/kg CNO (1mg/ml in saline) and immediately returned to the chamber with room air for 10 minutes, after which gas was changed to 5% CO2 for 15 minutes. The last 5 minutes of each segment (a, b, c, d, Figure 3A) were used for data analyses. Rectal thermocouple temperature was read immediately prior to placement in the chamber, upon removal for injection, and upon final removal. The average of these 3 temperatures was used in tidal volume calculation below.

Respiratory airflow was recorded in a 140 ml water-jacketed, temperature-controlled, glass chamber attached to a differential pressure transducer (Validyne Engineering) and reference chamber. Water temperature was 35.1°C, resulting in a chamber temperature of 34°C. An AEI Technologies pump pulled air through the chamber at ~ 325 ml/min. Volume calibrations were performed by repeated known-volume injections. Humidified gas flowing into the chamber was either room air or a 5% CO2 mix, balanced with air (medical grade). Pressure transducer readings were digitized at 1kHz (Powerlab, ADInstruments) and analyzed off-line for peak amplitude, peak frequency, and average voltage (LabChart 6, ADInstruments). Respiratory volume was determined by the following formula:

A=peak of breath signal (volts)

B=peak of signal for injection volume

C=volume injection (ml)

D= body temperature (°C)

E=chamber temperature (°C)

F=barometric pressure (mmHg)

G=pressure of water vapor of mouse = 1.142+(0.8017*D)−(0.012*D2)+(0.0006468*D3)

H=pressure of water vapor of chamber = 1.142+(0.8017*E)−(0.012*E2)+(0.0006468*E3)

Results were analyzed by two-way RM ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc analysis with inspired gas and CNO-administration as factors. The extent to which the V̇E response to 5% CO2 (the percent increase) was reduced upon CNO/Di-induced neuronal inhibition, here referred to as the “difference response,” was calculated as:

Electrophysiology

200 μm brainstem slices were prepared from P14–P18 or P23–P26 mice as reported for rats (Richerson et al., 2001): anesthetized mice were rapidly decapitated, removed brain was placed in ice cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF, in mM: NaCl 124, KCl 3, MgCl2 2, CaCl2 2, NaH2PO4 1.3, NaHCO3 26, dextrose 10; pH 7.4 at 5% PCO2/95% PO2) supplemented with kynurenic acid (1 mM), and vibratome sliced into a chamber filled with aCSF and bubbled with 5% CO2/95% O2 for 1 hour.

Brain slices were placed into a recording chamber mounted onto a fixed-stage Zeiss Axioskop equipped with 4x air and 40x water immersion objectives, Nomarski optics, epi-fluorescent illumination and filter detection of GFP and mCherry. The recording chamber was continuously irrigated (2.5–3ml/m) at RT with aCSF.

Patch electrodes were fabricated from capillary glass pulled to a DC resistance of 5–10M after filling with intracellular solution, inserted into an electrode holder and connected to the headstage of an amplifier (Molecular Devices). Patch pipettes filled with intracellular solution (in mM: KOH 135, methanesulfonic acid 135, KCl 10, HEPES 5, EGTA 1, ATP 3, GTP 0.5, pH 7.2) were used to form a gigaseal; current clamp recordings used whole-cell or perforated patch (48 μM gramicidin in intracellular solution).

Slices were superfused with aCSF containing picrotoxin 100 μM, AP-5 50 μM, and CNQX 10 μM. If neurons were not spontaneously active, depolarizing current was injected continuously while testing for chemosensitivity such that an adjusted baseline-firing rate of 0.6 Hz was achieved on average. Spontaneous firing rate reported in Figure 4I–J is that prior to current injection. All recordings were performed at RT (22–25°C). For testing chemosensitivity, membrane potential was amplified (Axopatch 700b, Molecular Devices), filtered (10 kHz low-pass), and acquired (National Instruments) using custom software. All other current-clamp recordings were collected using a Digidata 1200 board and Clampex software (Molecular Devices).

Testing for CO2/pH sensitivity was performed as described (Wang and Richerson, 1999; Wang et al., 2001). Changing the gas bubbling the bath solution from 5% CO2/95% O2 to 9% CO2/91% O2 decreased extracellular pH from ~7.4 to ~7.15. Bath pH was continuously measured via an inflow pH electrode; firing rate was continuously monitored. Neurons were considered chemosensitive if firing rate changed by at least 20% per 0.2 pH units in a manner reversible and reproducible over two or more exposures to 9% CO2 (at least 4 CO2 transitions), and with a consistent time course. The chemosensitivity index (CI) was calculated as described (Wang et al., 1998), using the slope of the log firing rate versus pH and representing the firing rate in response to a decrease in extracellular pH of 0.2 units as a percentage of control firing rate.

Since this method of analysis would result in a misleadingly large CI in neurons with low firing rates, depolarizing current was given in cases described above, and the CI modified if there was a downward drift in firing rate so that epochs of steady-state firing rate lower than 0.2 Hz at pH 7.4 were adjusted to 0.2 Hz (Wang et al., 2001). Fisher’s exact test was used to compare chemosensitive vs non-chemosensitive categories. For CI, baseline membrane potential, baseline firing rate, and change in firing rate data were analyzed by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Brain section illustrations in Figure 1G–I, Figure 2D, H, M, R, Figure 3, and Figures 5–7 modified from (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001).

Supplementary Material

HA-tag immunodetection of Di in somata of serotonergic neurons using derivative allele RC::FDi (Flpe-responsive) partnered with Pet1::Flpe, as compared to littermate control single transgenic RC::FDi (no Flpe) sibling tissue. Staining is shown throughout the serotonergic raphé including the Dorsal Raphé (panels are the same images as those shown in Figure 1F and J), Raphé Magnus, and Raphé Obscurus. Scale bar is 100 μm.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following National Institutes of Health Grants: F31NS073276 (RB), 5R21DA023643-02 (RB, SD), 5P01HD036379-13 (RB, AC, EN, GR, SD), P20NS076916 (GR), as well as support from Parker B. Francis Fellowship (AC) and VAMC (GR). The authors thank Bryan Roth for the Di cDNA and Russell Ray, Yuanming Wu, Matthew Hodges, and Hannah Kinney for technical assistance and/or helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: R.B. and S.D. conceived and designed the study. R.B. carried out the mouse breeding, histology, and electrophysiology, and assisted with plethysmography. A.C. performed whole animal plethysmography. G.R. provided equipment, technical assistance, and expertise for electrophysiological experiments. E. N. provided equipment, technical assistance and expertise for plethysmography experiments. R.B. and S.D. wrote the manuscript in collaboration with the other authors.

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5163–5168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700293104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awatramani R, Soriano P, Rodriguez C, Mai JJ, Dymecki SM. Cryptic boundaries in roof plate and choroid plexus identified by intersectional gene activation. Nat Genet. 2003;35:70–75. doi: 10.1038/ng1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccini G, Mlinar B, Audero E, Gross CT, Corradetti R. Impaired chemosensitivity of mouse dorsal raphe serotonergic neurons overexpressing serotonin 1A (Htr1a) receptors. PloS one. 2012;7:e45072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang SJ, Jensen P, Dymecki SM, Commons KG. Projections and interconnections of genetically defined serotonin neurons in mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35:85–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07936.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1112–1120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan GF, Richerson GB. Central serotonin neurons are required for arousal to CO2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16354–16359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004587107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean JB, Nattie EE. Central CO2 chemoreception in cardiorespiratory control. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:976–978. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00133.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean JB, Putnam RW. The caudal solitary complex is a site of central CO2 chemoreception and integration of multiple systems that regulate expired CO2. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;173:274–287. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depuy SD, Kanbar R, Coates MB, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. Control of breathing by raphe obscurus serotonergic neurons in mice. J Neurosci. 2011;31:1981–1990. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4639-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil V, Thoby-Brisson M, Rallu M, Persson K, Pattyn A, Birchmeier C, Brunet JF, Fortin G, Goridis C. Defective respiratory rhythmogenesis and loss of central chemosensitivity in Phox2b mutants targeting retrotrapezoid nucleus neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14836–14846. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2623-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman JL, Del Negro CA, Gray PA. Understanding the rhythm of breathing: so near, yet so far. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:423–452. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-040510-130049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JM. SSRI antidepressant medications: adverse effects and tolerability. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3:22. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v03n0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AJ, III, Koschnitzky JE, Ramirez JM. The Physiological Determinants of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013;189:288–300. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargaglioni LH, Hartzler LK, Putnam RW. The locus coeruleus and central chemosensitivity. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;173:264–273. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar P, Lillesaar C. Probing the diversity of serotonin neurons. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367:2382–2394. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich JA, Hen R. Dissecting the role of the serotonin system in neuropsychiatric disorders using knockout mice. Psychopharmacology. 2001;155:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s002130000573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guettier JM, Gautam D, Scarselli M, Ruiz de Azua I, Li JH, Rosemond E, Ma X, Gonzalez FJ, Armbruster BN, Lu H, et al. A chemical-genetic approach to study G protein regulation of beta cell function in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19197–19202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906593106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Bayliss DA. Central respiratory chemoreception. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:3883–3906. doi: 10.1002/cne.22435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks T, Francis N, Fyodorov D, Deneris ES. The ETS domain factor Pet-1 is an early and precise marker of central serotonin neurons and interacts with a conserved element in serotonergic genes. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10348–10356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10348.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilaire G, Voituron N, Menuet C, Ichiyama RM, Subramanian HH, Dutschmann M. The role of serotonin in respiratory function and dysfunction. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;174:76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges MR, Forster HV, Papanek PE, Dwinell MR, Hogan GE. Ventilatory phenotypes among four strains of adult rats. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:974–983. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00019.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges MR, Richerson GB. The role of medullary serotonin (5-HT) neurons in respiratory control: contributions to eupneic ventilation, CO2 chemoreception, and thermoregulation. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:1425–1432. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01270.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtman JR. Immunohistochemical localization of serotonin-and substance P-containing fibers around respiratory muscle motoneurons in the nucleus ambiguus of the cat. Neuroscience. 1988;26:169–178. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtman JR, Marion LJ, Speck DF. Origin of serotonin-containing projections to the ventral respiratory group in the rat. Neuroscience. 1990;37:541–552. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90422-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iceman KE, Richerson GB, Harris MB. Medullary serotonin neurons are CO2 sensitive in situ. J Neurophysiol. 2013;110:2536–2544. doi: 10.1152/jn.00288.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs BL, Azmitia EC. Structure and function of the brain serotonin system. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:165–229. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs BL, Fornal CA. Serotonin and motor activity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:820–825. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P, Farago AF, Awatramani RB, Scott MM, Deneris ES, Dymecki SM. Redefining the serotonergic system by genetic lineage. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:417–419. doi: 10.1038/nn2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Pedersen NP, Yokota S, Hur EE, Fuller PM, Lazarus M, Chamberlin NL, Saper CB. Glutamatergic Signaling from the Parabrachial Nucleus Plays a Critical Role in Hypercapnic Arousal. J Neurosci. 2013;33:7627–7640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0173-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel RA, Turnbull DH, Blanquet V, Wurst W, Loomis CA, Joyner AL. Two lineage boundaries coordinate vertebrate apical ectodermal ridge formation. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1377–1389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling L, Fuller DD, Bach KB, Kinkead R, Olson EB, Mitchell GS. Chronic intermittent hypoxia elicits serotonin-dependent plasticity in the central neural control of breathing. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5381–5388. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05381.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett-Barr MR, Mitchell GS, Satriotomo I, Johnson SM. Serotonin-induced in vitro long-term facilitation exhibits differential pattern sensitivity in cervical and thoracic inspiratory motor output. Neuroscience. 2006;142:885–892. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Perl ER. Selective action of noradrenaline and serotonin on neurones of the spinal superficial dorsal horn in the rat. J Physiol. 2007;582:127–136. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.131565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GS, Johnson SM. Invited Review: Neuroplasticity in respiratory motor control. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:358–374. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00523.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey DK, Stornetta RL, Weston MC, Simmons JR, Parker A, Bayliss DA, Guyenet PG. Respiratory control by ventral surface chemoreceptor neurons in rats. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1360–1369. doi: 10.1038/nn1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattie E, Li A. Central Chemoreceptors: Locations and Functions. Compr Physiol. 2012;2:221–254. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson DS, Trachtenberg FL, Thompson EG, Belliveau RA, Beggs AH, Darnall R, Chadwick AE, Krous HF, Kinney HC. Multiple serotonergic brainstem abnormalities in sudden infant death syndrome. JAMA. 2006;296:2124–2132. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattyn A, Vallstedt A, Dias JM, Samad OA, Krumlauf R, Rijli FM, Brunet JF, Ericson J. Coordinated temporal and spatial control of motor neuron and serotonergic neuron generation from a common pool of CNS progenitors. Genes Dev. 2003;17:729–737. doi: 10.1101/gad.255803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 2. Elsevier Academic Press; San Diego: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ptak K, Yamanishi T, Aungst J, Milescu LS, Zhang R, Richerson GB, Smith JC. Raphe neurons stimulate respiratory circuit activity by multiple mechanisms via endogenously released serotonin and substance P. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3720–3737. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5271-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray RS, Corcoran AE, Brust RD, Kim JC, Richerson GB, Nattie E, Dymecki SM. Impaired respiratory and body temperature control upon acute serotonergic neuron inhibition. Science. 2011;333:637–642. doi: 10.1126/science.1205295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray RS, Corcoran AE, Brust RD, Soriano LP, Nattie EE, Dymecki SM. Egr2-neurons control the adult respiratory response to hypercapnia. Brain Res. 2013;1511:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richerson GB, Buchanan GF. The serotonin axis: Shared mechanisms in seizures, depression, and SUDEP. Epilepsia. 2011;52(Suppl 1):28–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richerson GB, Wang W, Tiwari J, Bradley SR. Chemosensitivity of serotonergic neurons in the rostral ventral medulla. Respir Physiol. 2001;129:175–189. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(01)00289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severson CA, Wang W, Christopher A, Pieribone VA, Dohle CI, Richerson GB. Midbrain serotonergic neurons are central pH chemoreceptors. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1139–1140. doi: 10.1038/nn1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley MT, Fu L, Ennis M, Liu WL, Aston-Jones G. Dendrites of locus coeruleus neurons extend preferentially into two pericoerulear zones. J Comp Neurol. 1996;365:56–68. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960129)365:1<56::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachniak TJ, Ghosh A, Sternson SM. Chemogenetic Synaptic Silencing of Neural Circuits Localizes a Hypothalamus→ Midbrain Pathway for Feeding Behavior. Neuron. 2014;82:797–808. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohl KP, Thomas AJ, Jean PS, Schlenker EH, Koletsky RJ, Schork NJ. Ventilation and metabolism among rat strains. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82:317–323. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.1.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toward MA, Abdala AP, Knopp SJ, Paton JFR, Bissonnette JM. Increasing brain serotonin corrects CO2 chemosensitivity in methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (Mecp2) deficient mice. Exp Physiol. 2013;98:842–849. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.069872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Peoples J, Telegan P. Efferent projections of the nucleus of the solitary tract to peri- locus coeruleus dendrites in rat brain: Evidence for a monosynaptic pathway. J Comp Neurol. 1999;412:410–428. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990927)412:3<410::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderHorst VG, Ulfhake B. The organization of the brainstem and spinal cord of the mouse: relationships between monoaminergic, cholinergic, and spinal projection systems. J Chem Neuroanat. 2006;31:2–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voiculescu O, Charnay P, Schneider-Maunoury S. Expression pattern of a Krox-20/Cre knock-in allele in the developing hindbrain, bones, and peripheral nervous system. Genesis. 2000;26:123–126. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<123::aid-gene7>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss MD, De Castro D, Lipski J, Pilowsky PM, Jiang C. Serotonin immunoreactive boutons form close appositions with respiratory neurons of the dorsal respiratory group in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;295:208–218. doi: 10.1002/cne.902950205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Shi Y, Shu S, Guyenet PG, Bayliss DA. Phox2b-Expressing Retrotrapezoid Neurons Are Intrinsically Responsive to H+ and CO2. J Neurosci. 2013;33:7756–7761. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5550-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Pizzonia JH, Richerson GB. Chemosensitivity of rat medullary raphe neurones in primary tissue culture. J Physiol. 1998;511 (Pt 2):433–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.433bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Richerson GB. Development of chemosensitivity of rat medullary raphe neurons. Neuroscience. 1999;90:1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00505-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Tiwari JK, Bradley SR, Zaykin RV, Richerson GB. Acidosis-stimulated neurons of the medullary raphe are serotonergic. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2224–2235. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie CJ, Hendricks TJ, Zhang B, Wang L, Lu P, Leahy P, Fox S, Maeno H, Deneris ES. Distinct transcriptomes define rostral and caudal serotonin neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:670–684. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4656-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

HA-tag immunodetection of Di in somata of serotonergic neurons using derivative allele RC::FDi (Flpe-responsive) partnered with Pet1::Flpe, as compared to littermate control single transgenic RC::FDi (no Flpe) sibling tissue. Staining is shown throughout the serotonergic raphé including the Dorsal Raphé (panels are the same images as those shown in Figure 1F and J), Raphé Magnus, and Raphé Obscurus. Scale bar is 100 μm.