Abstract

Background

Molecular diagnosis of the distal spinal muscular atrophies or distal hereditary motor neuropathies remains challenging due to clinical and genetic heterogeneity. Next generation sequencing offers potential for identifying de novo mutations of causative genes in isolated cases.

Patient

We describe a 3.6 year old girl with congenital scoliosis, equinovarus and L5/S1 left hemivertebra who showed delayed walking and lower extremities atrophy. She was negative for SMN1 deletion testing and parents show no sign of disease.

Results

Whole exome sequencing of the affected girl showed a novel de novo heterozygous missense mutation c.1792C>T; (p.Arg598Cys) in the tail domain of the DYNC1H1 gene encoding for cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain 1. The mutation changed a highly conserved amino acid, and was absent from both parents.

Conclusion

De novo mutations of DYNC1H1 have been found in cases of autosomal dominant mental retardation with neuronal migration defects. Dominantly inherited mutations of DYNC1H1 have been reported to cause spinal muscular atrophy with predominance of lower extremity involvement (SMA-LED) and Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2O (CMT2O). This is the first report of a de novo DYNC1H1 mutation in the SMA-LED phenotype with a spinal deformity (lumbar hemi vertebrae). This case also demonstrates the power of next generation sequencing to discover de novo mutations at a genome-wide scale.

Keywords: spinal muscular atrophy with lower extremity predominance, SMALED, SMA-LED, distal spinal muscular atrophy, dSMA, whole exome sequencing, DYNC1H1, Charcot-Marie-Tooth

Introduction

The hereditary motor neuropathies (HMN), also known as distal spinal muscular atrophy (dSMA) or spinal Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT), are characterized by length-dependent neuropathies of primarily motor axons, although sensory axons could be minimally involved as well.1 Other associated features include pyramidal signs or myelopathy (neuronopathies).2 The current classification is based on phenotype and mode of inheritance (dominant, recessive). However, there is extensive genetic heterogeneity, with more than 18 disease-causing genes and varying phenotypes (Table 1). Molecular diagnosis by a candidate gene approach using traditional Sanger single gene sequencing methods remains problematic. The recent ability to carry out highly parallel DNA sequencing (nextgen) enables rapid scans of the patient’s entire genome for potential causative mutations. This approach has been particularly informative in isolated cases, where de novo mutations may be seen in the proband that are not seen in either parent. Here, we report the clinical and molecular work up of a young girl with a Spinal muscular atrophy with lower extremity predominance SMA-LED) phenotype using next generation (nextgen) methods.

Table 1.

Candidate gene list for distal SMA.

| # | Gene | Description | Disease (SMA) | Inheritance | OMIM | Other diseases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HSPB1 | heat shock 27kDa protein 1 | distal hereditary motor neuropathy, type IIB | AD, AR | 602195 | Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, axonal, type 2F |

| 2 | HSPB3 | heat shock 27kDa protein 3 | Neuronopathy, distal hereditary motor, type IIC | AD | 604624 | |

| 3 | HSPB8 | heat shock 22kDa protein 8 | distal hereditary motor neuropathy type IIA | AD | 608014 | Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, axonal, type 2L |

| 4 | BSCL2 | Berardinelli-Seip congenital lipodystrophy 2 (seipin) | distal hereditary motor neuropathy, type V | AD | 606158 | Lipodystrophy, congenital generalized, type 2; Silver spastic paraplegia syndrome |

| 5 | GARS | glycyl-tRNA synthetase | distal hereditary motor neuropathy, type V | AD | 600287 | Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, type 2D |

| 7 | AARS | alanyl-tRNA synthetase | distal hereditary motor neuropathy | AD | 601065 | Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, axonal, type 2N |

| 8 | DYNC1H1 | dynein, cytoplasmic 1, heavy chain 1 | Spinal muscular atrophy, lower extremity-predominant | AD | 600112 | Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, axonal, type 20; Mental retardation, autosomal dominant 13 |

| 9 | REEP1 | receptor accessory protein 1 | Neuronopathy, distal hereditary motor, type VB | AD | 609139 | Spastic paraplegia 31, autosomal dominant |

| 10 | IGHMBP2 | immunoglobulin mu binding protein 2 | Neuronopathy, distal hereditary motor, type VI (also DSMA1) | AR | 600502 | |

| 11 | PLEKHG5 | pleckstrin homology domain containing, family G, member 5 | Spinal muscular atrophy, distal, 4 (DSMA4) | AR | 611101 | |

| 12 | DCTN1 | dynactin 1 | Neuropathy, distal hereditary motor, type VIIB | AD | 601143 | Perry syndrome; susceptibility to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) |

| 13 | TRPV4 | transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily V, member 4 | Scapuloperoneal spinal muscular atrophy; Spinal muscular atrophy, distal, congenital nonprogressive | AD | 605427 | Brachyolmia type 3; Digital arthropathy-brachydactyly, familial; Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy, type IIc; Metatropic dysplasia; Parastremmatic dwarfism; Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, Maroteaux type; Spondylometaphyseal dysplasia, Kozlowski type |

| 14 | ATP7A | ATPase, Cu++ transporting, alpha polypeptide | Spinal muscular atrophy, distal, 3 (DSMA4) | X-linked | 300011 | Menkes disease; Occipital horn syndrome |

| 15 | DNAJB2/ HSJ1 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily B, member 2 | Spinal muscular atrophy, distal 5 (DSMA5) | AR | 604139 | |

| 16 | UBA1/UB E1 | ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 1 | X-linked infantile spinal muscular atrophy (XLSMA) | X-linked | 314370 | |

| 17 | VAPB | VAMP (vesicle-associated membrane protein)-associated protein B and C | Spinal muscular atrophy, late-onset, Finkel type | AD | 605704 | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 8 |

| 18 | SLC5A7 | solute carrier family 5 (choline transporter), member 7 | Neuronopathy, distal hereditary motor, type VIIA | AD | 608761 | |

| 19 | ? | linked to chromosome 9p21.1-p12 | Neuropathy, distal hereditary motor, Jerash type (DSMA2) | AR | 605726 | |

| 20 | ? | linked to chromosome 11q13.3 | Spinal muscular atrophy, chronic distal (DSMA3) | AR | 607088 |

Case report

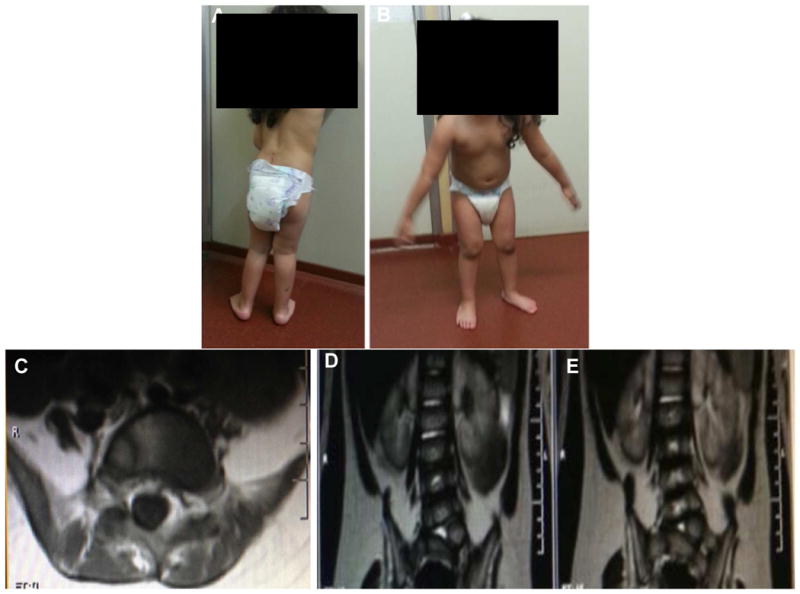

This female patient, with non-consanguineous healthy parents, was born after 40 weeks of gestation and presented with scoliosis and pes equinovarus deformity at birth. Pregnancy was complicated with gestational diabetes and hypothyroidism, which was treated, delivery was vaginal and uncomplicated. Growth parameters were within range of norms for gestational age at birth. In terms of motor development, the parents did not recall initial time for acquisition of early motor milestones. They reported that she was able to turn over at 10 months, and soon after she started crawling. She was able to walk with support at 15 months of age and independently at 2 years of age. Medical history was only significant for two typical febrile seizures. Physical examination at time of initial neurological evaluation at age 2 showed inability to rise from the floor, waddling gait, distal lower extremities atrophy and absent deep tendon reflexes on lower extremities only. Plantar responses were normal. She had increased scoliosis, calf atrophy (Figure 1A) and showed selective atrophy of lower extremities (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Patient at 3.6 years of age. Panel A: Patient in standing position showed left scoliosis and calf atrophy. Panel B: Patient in standing position showed selective atrophy of lower extremities. Panel C: Coronal and Panel D: Axial lumbarsacral spine MRI of patient (long and short arrow respectively) showed left vertebral anomaly (hemivertebra) corresponding to level L5/S1.

Clinical laboratory work up included normal levels of full blood count, creatine kinase, thyroid stimulating hormone, lactic acid and ammonia levels. Genetic analysis ruled out the deletion of SMN1, a common cause of SMA. Non-contrast brain MRI was normal. Spine MRI showed L5/S1 left hemivertebra (Figure 1C, 1D). Nerve conduction studies displayed normal motor and sensory conductions. Concentric needle electromyography of proximal and distal leg muscles showed no evidence of abnormal spontaneous activity along with decreased recruitment of high amplitude (5 to 7mV) motor units action potentials, consistent with a chronic neurogenic pattern On the most recent neurological examination at 3.6 years of age, the patient could walk unassisted but showed waddling gait. She has not had further deterioration of motor function. While standing, the patient demonstrated hyperlordosis of the spine. No sensory disturbance of ataxia has been recognized as of yet. Cognitive development was normal for age.

Results

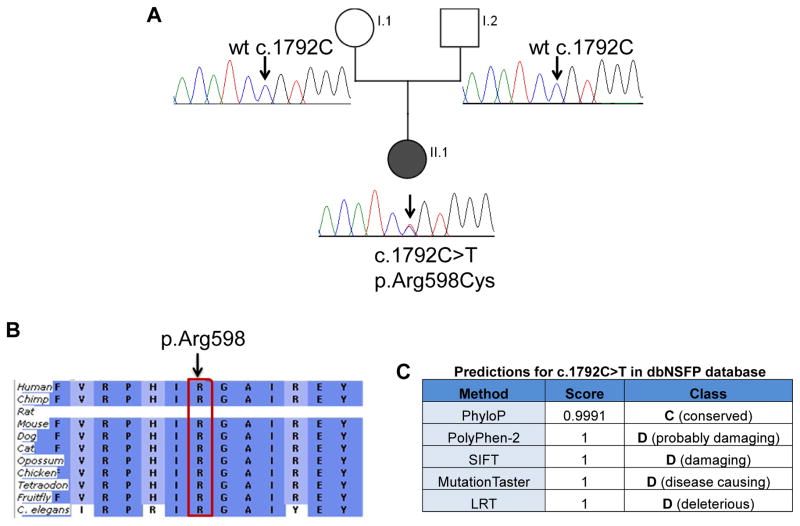

Exome sequencing of unaffected parents and affected proband was performed. Informed consent was obtained under protocol 2405 from the Office for the Protection of Human Subjects and Institutional Review Board at Children’s National Medical Center, Washington DC, USA. Exome enrichment was carried out using TruSeq exome enrichment kits (Illumina, San Diego, CA) with sequencing performed on the Illumina HiScan SQ sequencer (2x100cycles, paired end sequencing). Exome sequencing data was analyzed using NextGENe software (SoftGenetics, State College, PA) for alignment, variant calling and mutation detection. Filtering of variants was carried out by limiting to coding sequences, splice junctions (+/− 5 bases from exons), removing synonymous SNPs, and removing polymorphisms already reported in dbSNP and 1000Genomes. A candidate gene filter with 18 known dSMA genes (Table 1) was added to facilitate identification of known disease-causing variants associated with dSMA. A novel heterozygous variant c.1792C>T; (p.Arg598Cys) in DYNC1H1 (NM_001376.4) gene was found in the proband. We confirmed that the change occurred de novo in the patient including confirmation of maternity and paternity (data not shown); this variant was also confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 2A). All de novo variants for proband were further filtered against our in-house sequencing database; 12 de novo variants were studied to confirm DYNC1H1 as the best candidate gene for our proband. The DYNC1H1 c.1792C>T variant was absent from the NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) database which further confirms it is not a common variation. Overall coverage of exomes was ~ 35x. Coverage of candidate dSMA genes in our exome data was ~92% with coverage of 10x and ~96% with coverage of ~5x. Most dSMA exons with lower or no coverage showed high GC content which probably resulted in low hybridization efficiency.

Figure 2.

Detection of mutation in DYNC1H1. Panel A: Sanger sequencing confirmation of novel DYNC1H1 variant (NM_001376.4:c.1792C>T) in proband and parents. Sanger sequencing chromatograms confirm that both unaffected parents have normal alleles at position c.1792 (arrow) and proband is heterozygous at position c.1792C>T causing Arg at position 598 to be changed to Cys. Wt=wildtype. Panel B: Arginine (R) at position 598 in DYNC1H1 is a highly conserved amino acid (generated using Alamut and the Ensembl Compara dataset). Panel C: Pathogenicity prediction for c.1792C>T in dbNSFP (database for nonsynonymous SNPs’ functional predictions) with probability scores ranging from 0 to 1 (0 being benign and 1 being disease causing).

Discussion

Mutations in DYNC1H1 (dynein, cytoplasmic 1, heavy chain 1) have been known to cause autosomal dominant forms of axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2O (CMT2O; OMIM#614228), spinal muscular atrophy with lower extremity predominance (SMA-LED; OMIM#158600) and mental retardation with neuronal migration defects (OMIM#614563). DYNC1H1 mutations were first reported by Weedon et al. using whole exome sequencing in a large family with axonal CMT.3 Subsequently, other authors have reported missense mutations in the tail domain of DYNC1H1 in families with dominant spinal muscular atrophy with predominance of lower extremity involvement (SMA-LED or SMA-LED).4,5 More recently, de novo missense mutations have been reported in patients with severe cognitive disability, microcephaly and cortical development defects.6,7,8 The role of DYNC1H1 has thus seen an expansion in its phenotypic spectrum encompassing development of both the central and peripheral nervous systems (Table 2). This wide spectrum likely reflects the numerous functions of the dynein complex. Consistent with this, mutations in the cytoplasmic dynein DNCHC1 mouse ortholog of DYNC1H1 cause widespread neuronal deficits (Loa mouse; legs at odd angles).9 Loa mice show deficits in both proprioceptive sensory neurons and motor neurons.10,11 Altered dendritic morphology and reduced number of trigeminal motor neurons was also described in Loa mice.9

Table 2.

Reported mutations in DYNC1H1 gene: main clinical and laboratory features.

| Published reference | Inheritance/ Clinical phenotype | Clinical features | Other features | EDX/Biopsy/MRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weedon et al., 20113 (N.=23) | Dominant Axonal CMT disease | Delayed motor milestones, abnormal gait and difficulty running Distal LE weakness and wasting. Pes cavus deformity Ambulation maintain through adulthood |

Variable learning disabilities in some Variable sensory impairment in some |

Nerve conductions normal Sural nerve biopsy: axonal degeneration |

| Harms et al., 20124 (N=34) | Dominant (Three generation family) Dominant SMALED |

Waddling gait Difficulty running (Significant quadriceps weakness) Variable heel cord contractures |

1 patient with fasciculation of calves 1 patient with developmental delay and polymicrogyria |

NCS: Low amplitude CMAP and normal sensory responses EMG chronic denervation |

| Willemsen et al., 20125 (N=2) | Severe Mental retardation, cortical dysplasia and dimorphism | Severe mental retardation Inability to walk or speak Club feet Kyphoscoliosis Spastic quadriplegia Swallowing difficulties |

Short stature Microcephaly Small hands and feet with short toes Seizures |

CT Head: Enlarged ventricles, cortical malformation with wide opercular regions and abnormal flat cortex |

| Tsurusaki et al., 20126 (n=3) | Dominant, incomplete penetrance | Prominent weakness and atrophy of proximal muscles of lower extremities Waddling gate. Ambulant |

None reported | Muscle biopsy: severe grouping atrophy of type 2 fibers and sparse enlarged type 1 fiber |

| Poirier et al., 20137 (N=9) | Dominant | Early onset seizures Variable microcephaly 3 patients spastic quadriparesis 3 patients with foot deformity (axonal neuropathy) |

Severe Mental retardation, cortical dysplasia and dimorphism | MRI: posterior pachygyria Some frontal polymicrogyria or nodular heterotopia |

| Fiorillo et al., 20148 (N=2) | Dominant | Global developmental delay, cognitive delay, foot deformities at birth. Ambulation maintain through adulthood. |

Hyperlordosis, right curve scoliosis | Brain MRI: Perisylvian abnormal gyration and polymicrogyria. |

Abbreviations: SMALED (Spinal muscular atrophy with lower extremity predominance), EMG (Electromyogram), CMT (Charcot-Marie-Tooth), NCS (Nerve conduction studies), CMAP (Compound muscle action potential), CT (Computed tomography), MRI (Magnetic resonance imaging).

Our patient showed a de novo heterozygous variant c.1792C>T; (p.Arg598Cys) in exon 8 of DYNC1H1 which is present in the mutation hotspot tail domain (exon 5–15) of DYNC1H1, very close to the original p.Ile584Leu mutation as described by Harms et al.4 Other indications of pathogenicity include high conservation of Arginine at position 598 in 9 species (Figure 2B) and bioinformatics predictions of a deleterious effect on the protein by all disease prediction software algorithms (dbNSFP database)12 (Figure 2C).

The main clinical features of autosomal dominant SMA with DYNC1H1 mutations include congenital or very early onset patterns of weakness that are most severe in the proximal legs, and a static or minimally progressive course (Table 4). Our patient showed these symptoms along with an additional lumbar hemivertebra phenotype. A different missense mutation (H306R) in the tail domain of DYNC1H1 was described in a single family with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT 2O, OMIM 614228).3 Although the CMT2O family shares early childhood onset of symptoms with the families in the present study, their phenotype was that of length-dependent weakness and sensory loss. These studies support the concept that both motor and tail domain mutations differentially impair DYNC1H1 function, leading to variable involvement of the peripheral or central nervous systems. In contrast, the patient reported here uniformly showed predominant weakness in lower extremities without sensory abnormalities on examination or electrophysiology, a combination that led to classification as SMA-LED rather than CMT. Interestingly, 1 of 13 patients with CMT 2O was noted to have predominant proximal weakness similar to our SMA subject.3 This range of phenotypes is reminiscent of those found in patients with TRPV4 mutations, which causes congenital HMN, scapuloperoneal SMA, and CMT 2C (TRPV4, OMIM#605427).

Several forms of skeletal abnormalities have been previously reported in association with some forms of CMT, but not SMA-LED. Chen et al.11 reported a 3-generation family of CMT where individual affected individuals showed proportional short stature, vocal cord paresis, reduced height of the vertebral bodies, and dolichocephaly.13 Other cases of TRPV4 mutations have since been described showing association of skeletal dysplasia and peripheral neuropathy.14

From a clinical standpoint, this is the first reported case of a de novo DYNC1H1 mutation leading to co-occurrence of skeletal dysplasia and a SMA-LED phenotype. Next generation sequencing for detection of de novo mutations is an effective way to provide a molecular diagnosis, although it should be noted that both parents must also be subjected to exome sequencing (trio sequencing) in order to define such de novo mutations in the proband.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients and their families for their participation. The pathogenic variant described has been submitted to the ClinVar public database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/; Accession #SCV000154972, will be held until published).

Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (3R01 NS29525, EPH), and a Neurological Sciences Academic Developmental Award (K12 NS052159, CTR).

JP is a predoctoral student in the Molecular Medicine Program of the Institute for Biomedical Sciences at the George Washington University. This work is from a dissertation to be presented to the above program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Ph.D. degree.

SC is funded by the Muscular Dystrophy Association/USA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Harding AE. Inherited neuronal atrophy and degeneration predominantly of lower motor neurons. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, editors. Peripheral neuropathy. 2. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1993. pp. 1051–1064. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irobi J, Dierick I, Jordanova A, Claeys KG, De Jonghe P, Timmerman V. Unraveling the genetics of distal hereditary motor neuronopathies. Neuromolecular Med. 2006;8(1–2):131–46. doi: 10.1385/nmm:8:1-2:131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weedon MN, Hastings R, Caswell R, et al. Exome sequencing identifies a DYNC1H1 mutation in a large pedigree with dominant axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89(2):308–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harms MB, Ori-McKenney KM, Scoto M, et al. Mutations in the tail domain of DYNC1H1 cause dominant spinal muscular atrophy. Neurology. 2012;78(22):1714–20. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182556c05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsurusaki Y, Saitoh S, Tomizawa K, et al. A DYNC1H1 mutation causes a dominant spinal muscular atrophy with lower extremity predominance. Neurogenetics. 2012;13(4):327–32. doi: 10.1007/s10048-012-0337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willemsen MH, Vissers LE, Willemsen MA, et al. Mutations in DYNC1H1 cause severe intellectual disability with neuronal migration defects. J Med Genet. 2012;49:179–183. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poirier K, Lebrun N, Broix L, et al. Mutations in TUBG1, DYNC1H1, KIF5C and KIF2A cause malformations of cortical development and microcephaly. Nature Genet. 2013;45(6):639–47. doi: 10.1038/ng.2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiorillo C, Moro F, Yi J, et al. Novel dynein DYNC1H1 neck and motor domain mutations link distal spinal muscular atrophy and abnormal cortical development. Hum Mutat. 2014;35(3):298–302. doi: 10.1002/humu.22491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ilieva HS, Yamanaka K, Malkmus S, et al. Mutant dynein (Loa) triggers proprioceptive axon loss that extends survival only in the SOD1 ALS model with highest motor neuron death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(34):12599–604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805422105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hafezparast M, Klocke R, Ruhrberg C, et al. Mutations in dynein link motor neuron degeneration to defects in retrograde transport. Science. 2003;300:808–812. doi: 10.1126/science.1083129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen XJ, Levedakou EN, Millen KJ, Wollmann RL, Soliven B, Popko B. Proprioceptive sensory neuropathy in mice with a mutation in the cytoplasmic Dynein heavy chain 1 gene. J Neurosci. 2007;27(52):14515–24. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4338-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Jian X, Boerwinkle E. dbNSFP: a lightweight database of human nonsynonymous SNPs and their functional predictions. Hum Mutat. 2011;32(8):894–9. doi: 10.1002/humu.21517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen DH, Sul Y, Weiss M, et al. CMT2C with vocal cord paresis associated with short stature and mutations in the TRPV4 gene. Neurology. 2010;75:1968–1975. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ffe4bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho TJ, Matsumoto K, Fano V, et al. TRPV4-pathy manifesting both skeletal and peripheral neuropathy: a report of three patients. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158 (4):795–802. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]