Abstract

The populations at risk for HIV infection, as well as those living with HIV, overlap with populations that engage in heavy alcohol consumption. Alcohol use has been associated with high-risk sexual behavior and an increased likelihood of acquiring HIV, as well as poor outcome measures of disease such as increased viral loads and declines in CD4+ T lymphocytes among those living with HIV-infections. It is difficult to discern the biological mechanisms by which alcohol use affects the virus:host interaction in human populations due to the numerous variables introduced by human behavior. The rhesus macaque infected with simian immunodeficiency virus has served as an invaluable model for understanding HIV disease and transmission, and thus, provides an ideal model to evaluate the effects of chronic alcohol use on viral infection and disease progression in a controlled environment. In this review, we describe the different macaque models of chronic alcohol consumption and summarize the studies conducted with SIV and alcohol. Collectively, they have shown that chronic alcohol consumption results in higher levels of plasma virus and alterations in immune cell populations that potentiate SIV replication. They also demonstrate a significant impact of chronic alcohol use on SIV-disease progression and survival. These studies highlight the utility of the rhesus macaque in deciphering the biological effects of alcohol on HIV disease. Future studies with this well-established model will address the biological influence of alcohol use on susceptibility to HIV, as well as the efficacy of anti-retroviral therapy.

Keywords: AIDS, animal models, chronic binge drinking, ethanol, rhesus macaque, Simian Immunodeficiency Virus, virology

Introduction

HIV infection and alcohol abuse are both significant worldwide health concerns, and the populations affected by each overlap [1, 2]. There are an estimated 34 million people living with HIV infections worldwide, with the vast majority of these cases due to infection with HIV type-1 (HIV-1). The rates of new HIV-1 infections have remained steady over the past several years, with approximately 2.5 million new cases annually worldwide [1]. Alcohol abuse is estimated to result in 2.5 million annual deaths worldwide, and the WHO lists alcohol consumption as the third-greatest risk factor for disease and disability worldwide [2]. Additionally, alcohol abuse has been shown to significantly increase the risk of HIV transmission [3-8]. These observations show that as we strive to develop strategies to prevent HIV transmission and improve the health of those living with HIV, we must have a better understanding of how alcohol abuse affects the biological and immunological health of the affected populations.

Alcohol and HIV Disease

Among those living with HIV infections in the United States, alcohol abuse rates have been found to be nearly twice those of the general population, [9]. Alcohol abuse is also a major concern in other areas of the world with large populations of HIV-infected patients [10]. Therapeutic advances for HIV infection have greatly improved mortality rates among those living with HIV, subsequently generating a more chronic disease state [11-14]. Various co-morbidities, including alcohol abuse, are now important concerns for the effective management of patient health [15-17]. Because chronic alcohol abuse can alter immunological and metabolic pathways that also affect disease progression among HIV-infected patients, several studies have sought to evaluate how alcohol use impacts HIV disease measures [18]). In studies conducted prior to the widespread use of ART, several investigators examined the potential association between alcohol use and HIV disease progression, as determined by the development of AIDS. Most did not find an association between alcohol use and the diagnosis of AIDS [19-24]. Variations in study design, including a lack of repeated measures of alcohol consumption during the course of disease and variation in the measure of alcohol intake limited the ability of these studies to rigorously evaluate the relationship between alcohol consumption and HIV disease progression [18]. In studies of HIV cohorts conducted after ART use became widespread, HIV disease progression as determined by measures of higher viral loads or decreased CD4+ T cell counts, were independently associated with alcohol abuse, when controlling for ART use and adherence [25-28].

Other studies have shown that alcohol abuse reduced adherence to ART regimens and resulted in outcome measures consistent with HIV disease progression [29-31]. The intermittent use of ART regimens has become a major concern for patient health as well as public health, due to increased viral replication in the host, the potential development of ART-resistant virus, and the increased risk of virus transmission (including drug resistant phenotypes) to a new host [32, 33]. While alcohol abuse has been readily demonstrated to have an effect on ART adherence, it is more difficult to discern the effects of alcohol on biological processes affecting disease in human cohort studies.

Rhesus Macaque as a model for HIV-Disease

Since the 1980's, the use of non-human primates infected with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) as a model for HIV has substantially increased our understanding of HIV disease and has provided an effective tool for the development of HIV prevention measures [34-36]. Although studies conducted with large cohorts of HIV-infected humans have been major contributors to our understanding of HIV disease progression, the complex interactions between human behaviors, such as variations in alcohol consumption, engagement in risky sex, and other life-style choices are not easily controlled. Therefore, well-controlled studies in animal models are particularly advantageous for deciphering the specific mechanisms by which chronic alcohol affects HIV disease. The SIV-macaque provides an ideal tool to evaluate host:virus interactions in the presence of chronic alcohol. Variations in study design are important considerations when comparing studies with the SIV-macaque model; those pertinent to alcohol abuse studies are described below.

History of the SIV-Rhesus Macaque Model

Because the host range of HIV-1 is primarily restricted to humans, the best-characterized animal model of HIV disease is the old world macaque infected with isolates of SIV [37, 38]. Following the initial discovery of SIV and immunosuppressive disease in rhesus macaques at both the New England Primate Research Center (NEPRC) and the Tulane National Primate Research Center (TNPRC), several different isolates of SIV have been propagated and used to infect macaques as a model for HIV disease [34, 39]. The initial isolate from the TNPRC, named SIVDelta-B670, (B670) resulted from transfer of tissue from sooty mangabeys (Cerocebus atys) to rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), while the virus identified at the NEPRC, SIVmac251, (Mac-251) was isolated from rhesus macaques that displayed transmissible immunodeficiency; subsequent studies also traced its origin to sooty mangabeys [37, 38]. Sooty mangabeys, like several other species of primates, are the natural hosts of SIV strains, but typically do not develop disease (reviewed in [40]). Cross-species transmission of the viruses found in sooty mangabeys into Asian macaques induces an immunodeficiency disease that closely mimics HIV. While the rhesus macaque is the most commonly used animal model for HIV disease, two other species of macaques are also used: the cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fasicularis) and the pig-tailed macaque (Macaca nemestrina).

SIV Isolates for Studies of HIV-Disease

The SIV isolates, Delta-B670 and Mac-251 are both viral strains that are comprised of a mixture of closely related viral genotypes or quasispecies, and they are frequently prepared as uncloned virus stocks for use in pathogenesis and vaccine studies [41-43]. Several other SIV strains are used in macaque model studies, including additional isolates similarly derived from cross-species transmission of SIV from sooty mangabeys to macaques (such as SIVsmE660), or molecular clones derived from various stocks, such as SIVmac239, (Mac-239) derived from Mac-251 and the neurotropic clone, SIVmac17E, derived from Mac-239 [44-46]. SIV is similar in genome structure to HIV, and the SIV disease course in macaques closely mimics that of HIV in humans. However, the viruses differ from each other in several important ways that limit the evaluation of therapeutics and immune response which are specific to the unique features of HIV. These include the study of immune responses directed against specific HIV proteins, particularly the envelope protein. Additionally, since HIV and SIV differ in their ability to use the CXCR4 molecule for viral entry, disease processes that occur with the utilization of the CXCR4 molecule as a co-receptor cannot be analyzed with SIV isolates [47-49]. This has lead to the construction of HIV-SIV chimeric, molecular clones or SHIVs; many of which have replaced the SIV envelope gene of the Mac-239 molecular clone with envelope genes from HIV isolates [50, 51]. Several different SHIVs have been constructed and passaged through macaques to increase their infectivity and pathogenesis and recapitulate the immunosuppressive disease model of the SIV-macaque; there is a wide range of pathogenicity among SHIV isolates when inoculated into macaques [52, 53]. Further adding to the variability in SIV-disease studies are the differences observed among different preparations of SIV stocks [54]. Indeed the same isolate expanded on different cell types and stored in aliquots by various labs can differ significantly in composition, which in turn may lead to difference in mucosal transmission efficiency and infection dynamics within the host [54, 55]. These differences between various stocks of SIV as well as the diversity among the various isolates can all contribute to the variability of disease in the macaque model.

SIV-Disease in the Rhesus Macaque

Two different subspecies of rhesus macaques have been used in SIV studies, the Chinese and Indian origin rhesus, with Indian origin rhesus more commonly utilized [56]. These two subspecies display different disease courses following infection with the same virus stock. Infections with SIV isolates Mac-251 or B670 are less pathogenic in Chinese origin animals as compared to those of Indian origin, with lower viral loads, better maintenance of CD4+ T cells, and longer survival times observed [56-58].

Rhesus macaques of the same subspecies infected with commonly used SIV isolates also display individual variation in the rates of disease progression (as has been observed in humans), ranging from two months to several years, with the median time to death less than one year observed in most studies [59-62]. Animals have been grouped into rapid, intermediate and slow rates of disease progression, and the rate of disease progression can be predicted by in vitro infection of PBMC with SIV and measuring their replicative capacity [59]. While the diversity of SIV disease in the out-bred macaques is useful for modeling disease in human, this also necessitates the use of larger populations of animals in order to compare differences between treatment outcomes.

Alcohol Studies in Macaques

Macaques also provide a good model for studies designed to evaluate the mechanisms by which drugs of abuse, including alcohol, alter host responses. As detailed below, the rhesus macaque has been effectively used to model chronic alcohol abuse. When combined with SIV infections, this model provides a powerful tool to decipher the specific mechanisms by which alcohol affects host responses to HIV/SIV.

History of the Macaque Model for Chronic Alcohol Abuse

There is a history of alcohol consumption studies in primates that pre-dates their use in HIV/SIV pathogenesis [63]. Although more costly to study than rodents, they offered a significant advantage due to their physiological similarities to humans and the capability to study higher cognitive functions. Early published work utilizing non-human primates in alcohol consumption studies dates back to the 1960s, where oral self-administration of ethanol in rhesus macaques was studied in response to stress, using a shock avoidance procedure [64, 65]. These studies showed that monkeys would self-administer considerable amounts of alcohol orally, with 4 - 6.5 g of ethanol/per kg of body weight consumed by some animals during the shock avoidance protocols. Self administration of ethanol via an intravenous catheter was first described in a study with five rhesus macaques, where a range of ethanol amounts was self-administered by the animals, including none or limited administration, to as high as 8.6 g/kg/day. The animals displayed severe symptoms of alcohol described as “severe motor inco-ordination and stupor”, and two of the animals died during the course of the study due to suffocation from respiratory complications [66]. Similar studies with intravenous administration of ethanol also showed that some macaques would demonstrate physical dependence on alcohol and would self-administer severely intoxicating doses of ethanol [67, 68]. These early studies established that rhesus macaques were capable of consuming large amounts of alcohol.

Free-Drinking Macaque Model of Chronic Alcohol Use

Investigators have utilized a variety of oral self-administration models for studies of alcohol drinking behavior in the non-human primate model. Various initiation protocols have been established for self-administration of alcohol, including the use of stress-induced conditioning through shock avoidance, food and water deprivation, or social stressors [64, 65, 69, 70]. Grant and Johanson demonstrated that ethanol polydipsia could be induced by positive reinforcement, using the intermittent delivery of sucrose-food pellets in non-food-deprived rhesus macaques [71]. This conditioning ultimately provided an initiation procedure that could reliably establish consistent ethanol self-administration, and thus be a true model of ethanol addiction [72]. Vivian et al. used this procedure to induce 4% ethanol self-administration in cynomolgus monkeys [73]. Following an induction period, animals were given access to ethanol and water 22 hours/day. Individual differences were found in the amount of ethanol consumed by an animal, ranging from 0.6 to 4.0 g/kg/day (BEC between 5 and 235 mg/dl). Stable drinking patterns were observed over time for individual animals, allowing them to be grouped into heavy, moderate, and light drinkers. Animals classified as heavy drinkers consumed an average of 3.4 g/kg daily, while moderate and light drinkers consumed average daily amounts of 1.92 and 1.1 g/kg, respectively. In this study, 50% of males and 12% of females were classified as heavy drinkers. Overall, a mean ethanol intake of 2.6 g/kg and 1.7 g/kg was observed in males and females respectively, demonstrating lower drinking levels collectively in the females. Animals maintained a positive caloric balance and experienced weight gain [73]. Additional studies with this model have demonstrated highly similar ranges of alcohol consumption (1.2 – 4.2 g/kg/day) in both cynomolgus and rhesus macaques. [74-77].

Free-Drinking Model and SIV Disease

Two studies with SIV-infected macaques have utilized an oral alcohol self-administration model to evaluate the effects of alcohol abuse on SIV disease. Both studies established a self-drinking model in rhesus macaques following protocols that included an induction phase with the removal of water and food for short periods of time, followed by replacement with flavored ethanol solutions for defined drinking sessions [69, 78]. In the SIV study conducted by Kumar et al., male macaques were introduced to alcohol via a two-step addiction protocol that included a two-hour water deprivation period, followed by access to an 8.4% ethanol/NutraSweet solution for one hour a day, for a period of 7 days. Following the one-week induction, animals were deprived of water overnight, then allowed access to the 8.4% ethanol/NutraSweet solution for 3 hours daily. Macaques in the control group followed the same 2-step protocol in which they were allowed to drink NutraSweet solution under comparable conditions. Following a 7-week period where alcohol or control drink were provided daily, animals were inoculated with a viral mixture comprised of both SIV and SHIV isolates [79].

A second SIV and alcohol self-administration study performed by Marcondes et al., employed a similar protocol of flavored ethanol conditioning. This conditioning strategy involved the gradual increase of both the concentration of ethanol mixed with flavoring (Tang ® Kraft Foods Inc,) as well as the total amount of ethanol solution available to the animal in a drinking session. Increases in ethanol content and availability continued until a target solution concentration of 6% (w/v) ethanol, provided at a level of 3.0 g/kg/session was achieved. For the SIV-alcohol experiments, four animals were deprived of water for 1 hour then given access to a 6% (w/v) ethanol/ 6% (w/v) Tang, limited to 3.0 g/kg in two 1 hour daily sessions. Control animals followed identical protocols without ethanol. Following a 30-day period of alcohol/control drink access, animals were inoculated with SIV [80].

In both of these SIV studies, similar wide ranges of alcohol consumption were observed (approximately 0.8 – 3.8 g/kg daily). Despite the small numbers of animals utilized, the range of ethanol consumption levels observed were highly similar to those reported in animals provided with alcohol in the positive reinforcement induction models [73]. Interestingly, in the study by Marcondes et al. the amounts of alcohol consumed by the animals declined in the days after SIV inoculation. Animals were only evaluated for 12 days post inoculation and the amounts consumed were recorded daily [80]. In the study by Kumar et al. a reduction in amount of alcohol consumed after SIV inoculation was not observed in the weekly reported values for 24 weeks post SIV infection. Although there was variation among individual animals, the overall consumption ranges were similar in the pre- and post- SIV infection periods between groups [79]. The range of alcohol consumption levels and the possibility that drinking patterns may change over the course of SIV-disease, represent important considerations in the design of studies to evaluate the effects of alcohol on SIV disease.

Gastric-Infusion Macaque Model of Chronic Alcohol Use

The majority of the SIV studies using rhesus macaques to evaluate the effects of alcohol abuse on disease progression have used a model of intragastric ethanol delivery, as initially described by Bagby et al. [81, 82]. In these studies, conducted by our group at LSU in collaboration with veterinarians at the TNPRC, we chose to provide a consistent amount of ethanol due to the variability in alcohol consumption rates. Therefore as a model of chronic binge drinking in humans, animals were infused with 30% ethanol in water (w/v) via an intragastric catheter at an amount that would produce a BEC of 50-60mM (or approximately 235 mg/dl).

For these studies, intragastric catheters were surgically implanted and routed via a tether to the top of the animal's cage. Approximately two weeks after insertion of the catheter, animals assigned to the ethanol treatment group received infusions of alcohol through the catheters at an initial dose of 2.5 g/kg body weight to titrate amounts of alcohol necessary to achieve 50-60 mM ethanol concentration in blood 90 minutes after the infusion; amounts were adjusted, as needed, based on BEC measurements. Animals received regular infusions of the determined volumes of ethanol, while animals in the control group received isocaloric sucrose. Animals receiving either the sucrose or alcohol treatments were observed to have similar, age-appropriate increases in body weight over the course of the study [81].

In the first studies conducted by our group, the chronic-binge alcohol model utilized a delivery schedule in which animals were given alcohol or sucrose on four consecutive-days each week. In these sessions, alcohol or isocaloric sucrose was delivered to the animals over a 5-hour period, which included a 30-minute priming period, followed by infusion of a maintenance dose of ethanol for the next 4.5 hours. After 3 months of treatment, animals were inoculated with SIV, and the alcohol or sucrose delivery schedule was maintained for the duration of the study. In more recent studies, we have utilized a 7-day per week delivery protocol, where ethanol was delivered daily via gastric catheter in a 0.5-hour infusion at a level that achieved BEC of 50-60mM, 90 minutes after the conclusion of the infusion. Although the BEC was not elevated for the same duration of time each day as previously achieved with the 5-hour infusion protocol, they were exposed to alcohol daily.

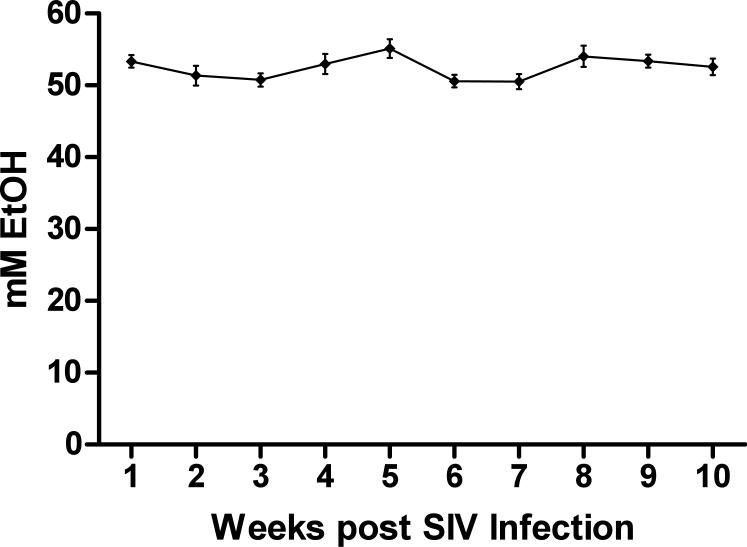

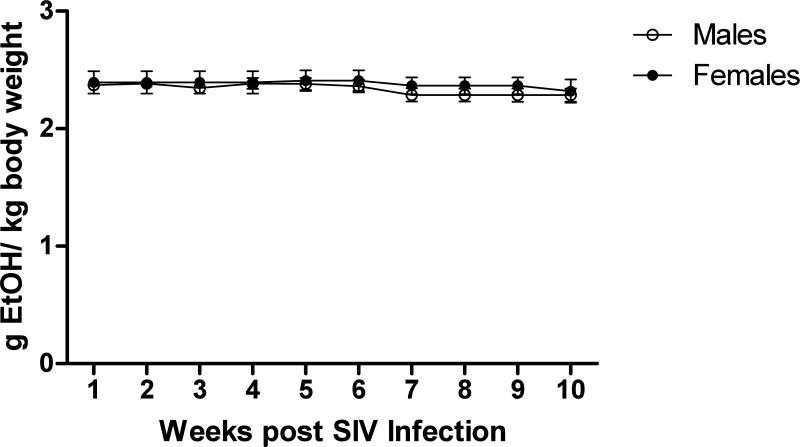

As shown in Figure 1, the 7-day intragastric alcohol delivery protocol allows for consistent maintenance of BEC within the 50-60 mM range over the SIV study period. An average BEC of 52.45 mM was observed over the 10-week course in a group of 18 animals. Figure 2 shows the average daily amounts of alcohol that were delivered to animals weekly over the first 10-weeks of SIV infection. Males and females received a similar daily dose of ethanol over the study course with males receiving an average of 2.34 and females 2.38 grams/kg to achieve target BEC. These results show that SIV-infected animals required similar levels of ethanol pre-and post SIV infection in order to reach the target BEC. The average daily amount of ethanol delivered in our current study (2.3 g/kg) falls within the range of alcohol consumption amounts observed in free-drinking models, where heavy drinkers have been shown to consume an average of 3.4 g/kg/day, while moderate drinkers consume 1.9 g/kg/day [73]. Likewise, the BEC achieved in our studies was similar to the BEC observed in the heavy drinkers in the free-drinking model.

Figure 1.

BEC in peripheral blood. Mean levels of ethanol in peripheral blood of 18 animals receiving daily treatment. Ethanol levels were measured at weekly intervals. Standard error of the mean is shown.

Figure 2.

Ethanol Delivery over SIV course in males and female. Average daily amounts of ethanol delivered via gastric infusion in the weeks after SIV infection in male (n=12 ) and female (n=6) animals. Standard error of the mean is shown.

Chronic Binge Alcohol and HIV/SIV Disease Progression: Studies in the Rhesus Macaque

Viral Load and Survival

As described above, there is considerable variability among the different SIV-macaque models of HIV disease utilized by various investigators as well as the macaque models of chronic alcohol consumption. Table 1 summarizes five alcohol-abuse studies conducted in the SIV-infected rhesus macaque, which have varied in SIV inoculum strain, route of infection, age of animals, and amounts of alcohol administered. Despite the differences in study design, four of these studies demonstrated significantly higher plasma viral loads in alcohol-treated animals at time points during the 8-12 weeks post infection, as compared to control animals in the respective study [79, 83-85]. The design of the fifth study included in these comparisons varied significantly from the others, in that the animals were sacrificed at 12 days p.i. for tissue collection. This precluded comparison of viral levels at set-point (8-12 weeks p.i.), and no differences were observed between the two groups during the acute phase of the disease [80].

Table 1.

SIV-Alcohol Studies

| Study | # Animals ALC/CTL1 | Age (yrs) | Alcohol Delivery | Average Alcohol Amounts Delivered | Time ALC prior SIV | SIV Strain | Route of Inoculation | Plasma Viral Load1 (log RNA copies/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALC | CTL | ||||||||

|

Bagby 2006[83] |

8/8 | 4 - 6 | Gastric Catheter |

2.4 g/kg/day 4 days/wk |

3 mo | SIV-B670 | IV | 4.85 | 3.64 |

|

Poonia 2006[85] |

7/8 | 3.4 - 5.1 | Gastric Catheter |

3.4 g/kg/day 4 days/wk |

8 wks |

SIV- Mac251 |

Rectal | 4.25 | 3.69 |

|

Kumar 2005[79] |

3/3 | 1.5 - 2.5 |

Oral self- admin. |

Varied 0.8-3.8 (range)3 g/kg/day 7 days/wk |

7 wks |

SHIVKU-1B SHIV89.6P SIV/17-E-Fr |

IV | 5.16 | 4.364 |

|

Nelson 2013[113] |

12/12 | 4 - 6 | Gastric Catheter |

13-14 g/kg/wk5 Mixed cohort 4 or 7 day/wk |

3 mo | SIV- Mac251 |

IV | 6.27 | 5.69 |

|

Marcondes 2008[80] |

4/4 | Not Stated |

Oral self- admin. |

2.88 (avg) g/kg/day 7 days/wk |

30 days |

SIV- Mac2516 |

IV | Similar at 12 days PI7 |

|

ALC- alcohol-treated animals; CTL – control animals

2Viral loads at set point (average VL at 60 and 90 days pi) are shown unless noted; reported data was log transformed for comparison purposes.

Values were estimated from published figure.

Viral loads at 12 weeks p.i.

8 ALC-treated animals received average of 3.4 g/kg/day -4 days per week and 4 ALC treated animals received approximately 2.3 g/kg/day-7 days per week.

Virus was adapted for replication in Chinese rhesus macaques

Actual values not reported

While several of these SIV-alcohol studies demonstrated an effect of chronic alcohol use on viral loads at set points, one study using a large cohort of SIV-infected animals over a three-year period, was designed to allow a more comprehensive evaluation of alcohol's influence on disease progression and survival time to end-stage disease [83]. Prior to the initiation of the study, a cohort of 32 male rhesus macaques was pre-screened using an in vitro SIV-infection assay to predict the animal's disease course post-infection [59]. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were infected with SIVDeltaB670 and assessed for viral replication kinetics. Using this assay, animals that were predicted to become rapid progressors were not selected for the SIV-infection arms of the study, and 16 animals predicted to be the slow progressors (based on in vitro viral replication levels) were evenly stratified by viral kinetics results into alcohol and sucrose treatment groups. Using the 4-day/week chronic-binge alcohol model, animals were exposed to alcohol or sucrose treatments for 3 months prior to SIV-infection. Peak plasma viral loads (2 weeks p.i.) were similar between the groups, however at viral set-point, significantly higher plasma viral loads were found in alcohol-treated animals. Animals were monitored for disease progression and euthanized when they reached specific criteria for end-stage disease (see Bagby et. al for details [83]). While all animals experienced at least one organ failure at the time that end-stage disease criteria were met, alcohol-treated animals displayed more gastrointestinal pathologies and neurological disease symptoms than control animals. Survival analysis indicated that the disease course was accelerated in alcohol-treated animals as compared to the sucrose-treated group, with a median survival time for ALC/SIV+ of 374 days as compared to 900 days for the SUC/SIV+ (p<0.05). [83]. Subsequent studies by our group have also observed higher plasma SIV loads in alcohol-treated animals as compared to controls, although some have not reached statistical significance or differences were observed at earlier time points post-inoculation. SIV-chronic alcohol studies in macaques have evaluated how HIV infection impacts multiple systems in the body, ranging from the hallmark immunodeficiency to neurocognative deficits and wasting syndrome. As summarized in Table 2, several SIV-alcohol studies in rhesus macaques have used a systems approach to further define the mechanisms by which chronic alcohol abuse affects HIV disease processes.

Table 2.

Chronic Alcohol Administration and SIV Disease: Systems Approach

| Study | # Animals | Inoculum | Major Findings (Compared to CTL animals) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic | |||

| Molina[90, 91] | 16 | SIV-B670 | Chronic ALC/SIV+ animals had decreased caloric intake and food preference changed from chow to treats and fruit, resulting in a decreased nitrogen balance. Inflammation in muscle tissue with increased TNF-α mRNA expression. |

| CNS | |||

| Winsauer[82] | 141 | SIV-B670 | Behavior deficits were potentiated in ALC/SIV+ animals compared to either agent alone. |

| Kumar[79] | 6 | SHIVKU-1B SHIV89.6P SIV-17E-Fr | CSF viral load remained elevated in the ALC/SIV+ group (5.15 log copies RNA/ml average at 24 wks), while it was undetectable after week 18 in the control group. |

| Mucosal & Immune | |||

| Poonia[85, 106] | 6 | SIV-Mac251 | After 2 months of ALC treatment, increased percentage of central memory and naïve CD4+ T cells and decreased percentages of effector memory CD8+ T cells found In duodenal tissue. After SIV infection (9-12 weeks pi), higher SIV RNA levels found in intestinal tissues of ALC animals. |

| Nelson[113] | 24 | SIV-Mac251 | Levels of SIV elevated in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid after S. peumoniae infection of lung (5.02 log10 copies/ml fluid in ALC and 4.33 in controls). In ALC animals, increased inflammation in lungs and increase in NF-κB activation 1 day post-pneumonia as compared to controls. |

| Immune | |||

| Marcondes[80] | 8 | SIV-Mac2512 | Reduced levels of circulating memory CD4+ T cells and increased CCR5+ monocytes in ALC animals during acute disease stage as compared to controls; lower levels of CD4+ T cell populations in several organs of ALC animals at day 12 p.i. |

| Pahar[116] | 24 | SIV-Mac251 | Despite higher plasma viral loads in alcohol treated animals, similar adaptive immune responses were observed in both groups. Magnitude of cell-mediated responses correlated with viral load, and neutralizing antibody titers were similar. |

Animal cohort comprised of 4 animals ALC/SIV, 4 animals VEH/SIV, 3 animals ALC, 3 animals VEH

Virus was adapted for replication in Chinese rhesus macaques

Metabolism and Muscle Wasting

AIDS-associated wasting remains a prevalent clinical issue, despite the availability of ART [86-88]. Alcohol abuse has also been shown to affect an individual's nutritional state as well as cause skeletal muscle myopathy [89]. The combined effects of HIV and alcohol have been evaluated in the SIV-macaque model, where caloric intake, weight, and body mass index can be measured in a well-controlled setting. The animal's diet consisted of monkey chow, fruits, and/or treats that were provided ad libitum. Macaques exposed to chronic alcohol prior to and over the course of SIV-infection demonstrated an overall reduction in caloric intake, as well as a change in food preference, when compared to sucrose-treated controls. Alcohol-treated animals exhibited a predilection for sweet foods, increasing their caloric intake from fruits and treats with an associated decrease from chow [90]. During the primary and asymptomatic stages (no clinical manifestations of disease) of SIV infection, only minimal differences in body weight were observed between alcohol- and sucrose-treated macaques [83, 90]. However, at end-stage disease alcohol-treated animals experienced less weight gain than sucrose controls (0.52 ± 0.25 kg vs. 1.6 ± 0.3 kg). Changes in body mass index (BMI) correlated with observed weight trends, with significantly lower BMI in alcohol-treated animals, as compared to sucrose controls (42.8 ± 1.4 kg/m2 vs. 49.1 ± 1.6 kg/m2), which had maintained their pre-SIV determined BMI [91]. The impact of chronic alcohol on metabolic, biochemical, and immune parameters during SIV infection were also evaluated and are more thoroughly described in another review from this issue (Molina, 2014).

Central Nervous System

The prevalence of HIV-associated dementia, the most severe classification of HIV-associated neurocognitive defects (HAND), has decreased with the widespread use of ART, however mild to moderate cognitive defects are still common in those living with HIV [92-96]. Furthermore, neurocognitive disorders have been associated with an increased risk of death in people with AIDS [97]. Additionally, alcohol abuse has adverse effects on neurocognitive function; clinical studies have demonstrated an additive adverse effect between alcohol dependence and HAND [98, 99]. The alcohol-SIV-macaque model provides an ideal system to evaluate neuropsychological changes and investigate the interaction of HAND and alcohol abuse. Studies have investigated the potential biological and neurobehavioral interactions of SIV in alcohol-treated macaques. The study by Winsauer et al, measured rate and accuracy in multiple schedules of repeated acquisition and performance of response chains. Neuropsychological deficits were greater in the ethanol-treated SIV-infected macaques compared to either SIV or ethanol alone [82]. Kumar et al., showed an increase in CSF viral load for the alcohol-treated animals beginning at 10 weeks p.i., while the control group remained relatively low and became undetectable by 18 weeks p.i. [79]. This study included the strain SIV/17E-Fr in the mixed virus inoculum, because it is a highly neurotropic virus known to cause AIDS-related neurological deficits. Based on their quantitative assay, SIV/17E-Fr was the only viral strain to cross the blood-brain barrier in the study [79]. In contrast, a third study by Marcondes et al,. detected significantly lower levels of virus in CSF of ethanol-treated macaques relative to vehicle at necropsy (day 12) [80]. This could be due to differences in the challenge stock of SIV, the acute-stage study desgin, and/or the small sample size.

Gut Mucosa

The mucosal immune system is a primary target for HIV infection due to the abundance of CD4+ T lymphocytes target cells present. The gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) is an early site of CD4+ T cell depletion and high viral replication [100-102]. The dramatic loss of helper T cells, in particular memory subpopulations, compromises the immune response and contributes to disease progression. Alcohol also affects the gut mucosa, in particular the integrity of the epithelial barrier [103-105]. Studies in the macaque model have shown that after two months of chronic alcohol consumption (but prior to SIV infection), a higher percentage of intestinal CD3+CD4+ lymphocytes and a lower percentage of CD3+CD8+ lymphocytes were found in alcohol-treated animals as compared to controls [106]. Further assessment of T lymphocyte memory subpopulations in the duodenum demonstrated that chronic alcohol consumption significantly increased the percentage of central memory (CD95+, CD28+) CD4+ T lymphocytes in the intestine and significantly decreased the percentage of effector memory (CD95+, CD28-) CD8+ lymphocytes after alcohol treatment. Following inoculation with SIV, higher levels of virus were found in the jejunum and colon of alcohol-treated animals. The observed increase of SIV target cells in the gut could potentially explain the higher levels of SIV noted in the plasma and gut of alcohol treated animals. No differences were noted in peripheral CD4+ or CD8+ T lymphocyte populations [85, 106].

Respiratory System

Respiratory associated opportunistic infections, such as bacterial pneumonia due to Pneumocystis jirovecii or more recently Streptococcus pneumoniae, are a common complication of HIV disease [107-109]. An increased incidence of lung infections has also been seen with alcohol abuse [110-112]. Infections by opportunistic pathogens and the subsequent immune response have been associated with an increase in HIV RNA levels, and therefore, these infections have the potential to influence disease progression [110-112]. To investigate how localized lung infections could influence HIV disease in a host exposed to chronic alcohol consumption, Nelson et al. designed a study using SIV-infected macaques exposed to chronic alcohol [113]. During the chronic stages of SIV-infection, alcohol and sucrose treated animals were inoculated with S. pneumoniae into the lung and SIV levels were measured in both plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). Prior to S. pneumoniae challenge, similar levels of SIV RNA were found in BALF of alcohol- and sucrose-treated animals. After the right lung was exposed to S. pneumoniae, a significant increase in SIV levels in BALF were observed in the right lung, with alcohol-treated animals higher than those of sucrose controls. Over the next two weeks, SIV levels in BALF of alcohol-treated animals remained approximately 10-fold higher than SIV levels in BALF from sucrose-treated controls. The increased viral replication was primarily found in the lungs, with only a slight increase in plasma viral load after S. pneumoniae infection. In conjunction with increased viral load in the lung, alveolar macrophage NF-κB activity was increased for both treatment groups 1 day post-challenge, with a trend to higher levels in the alcohol-treated animals. Activation of NF-κB has been linked to HIV/SIV replication and suggests a potential mechanism for elevated viral loads [114]. The levels of several cytokines increased after S. pneumoniae infections in all animals, with alcohol-treated animals trending to higher levels of TNF-α. Cytokine levels in the lung returned to near baseline by day three post lung infection [113].

Adaptive Immunity to SIV

An integral component in controlling HIV pathogenesis is the adaptive immune response, in which virus-specific cellular and humoral immune responses can influence viral load and lead to effective control of viral replication [115]. The effect of chronic alcohol on the development of SIV specific immune responses was recently evaluated by Pahar et al. Similar absolute numbers of peripheral blood CD8+ T-cells and CD4+ memory subsets were seen in alcohol and sucrose animals, although a significant decrease in central (CD28+CD95+) and effector (CD28-CD95+) memory CD4+ T-cells was noted in animals exposed to alcohol prior to SIV inoculation [116]. Similarly, Marcondes et al. observed a significant decrease in peripheral CD4+ central (CD62L+CD45RA-) and effector (CD62L-CD45RA-) memory lymphocyte frequency with chronic alcohol administration relative to vehicle treated macaques [80]. Overall, this study did not observe impairment in cell-mediated or humoral immune responses with chronic binge ethanol treatment. Similar titers of envelope-specific IgG were found in blood and the levels of neutralizing antibody were similar in both groups of animals, as measured in vitro with an easily neutralized strain of SIV. Similar cell-mediated responses to gag, nef and env proteins developed in both groups of animals and were correlated with the magnitude of viral replication. Although differences in immunological responses were not observed using reference viral isolates, further studies that evaluate the specific viral genotypes expressed in alcohol and sucrose-treated animals are needed. These studies can determine if the higher viral replication levels observed in alcohol-treated animals are due to the selective expression of more viral genotypes that escape immune control.

Summary

The SIV-infected macaque has proven to be a valuable model system for the study of HIV-disease and for the evaluation of co-morbidites such as chronic alcohol abuse. The macaque is easily adapted to studies of chronic alcohol consumption, and animals will consume clinically significant amounts of alcohol. Several studies have effectively utilized self-administration or gastric infusion of ethanol to evaluate the impact on SIV-disease. This model has proved especially useful for evaluating direct interactions of alcohol consumption in the absence of other behavioral factors that typically confound studies in humans. Studies to date in the macaque have shown that chronic alcohol abuse results in higher levels of viral replication in plasma and in gut-associated lymphoid tissue. They have also identified changes in mucosal lymphocyte populations that would facilitate replication of the virus. The changes in mucosal cell population may also enhance the susceptibility to infection, and future studies with the macaque model can directly address acquisition of virus and identify alcohol-induced changes in the genital microenvironment that increase the likelihood of infection. Similarly, higher levels of viral replication may also increase viral loads in genital fluids, increasing the potential for transmission to a new host. Studies focused on mucosal viral shedding in the genital compartment can also be effectively modeled in the macaque model.

As the population of people living HIV continues to increase, effective control of viral replication is an essential component of preventing morbidity and mortality as well as transmission. Managing co-morbidities that may exacerbate HIV disease and transmission, such as the abuse of alcohol, should be an important part of our prevention efforts. The macaque model of HIV infection provides a powerful tool that will be highly useful for the development and testing of therapeutics to treat and prevent HIV disease in the presence of alcohol use.

Acknowledgments

The author's work is supported by Supported by NIAAA-00983 and NIAAA-007577.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The author's work is supported by Supported by NIAAA-00983 and NIAAA-007577. The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.UNAIDS UNAIDS World AIDS Day Report. 2012.

- 2.WHO . Global Status Report on Alcohol and Healt. World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher JC, Bang H, Kapiga SH. The association between HIV infection and alcohol use: a systematic review and meta-analysis of African studies. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(11):856–63. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318067b4fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, et al. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prev Sci. 2007;8(2):141–51. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koblin BA, Husnik MJ, Colfax G, et al. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. Aids. 2006;20(5):731–9. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216374.61442.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erbelding EJ, Hutton HE, Zenilman JM, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in sexually transmitted disease clinic patients and their association with sexually transmitted disease risk. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(1):8–12. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000105326.57324.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trocki KF, Leigh BC. Alcohol consumption and unsafe sex: a comparison of heterosexuals and homosexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4(10):981–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stall R, McKusick L, Wiley J, et al. Alcohol and drug use during sexual activity and compliance with safe sex guidelines for AIDS: the AIDS Behavioral Research Project. Health Educ Q. 1986;13(4):359–71. doi: 10.1177/109019818601300407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galvan FH, Bing EG, Fleishman JA, et al. The prevalence of alcohol consumption and heavy drinking among people with HIV in the United States: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(2):179–86. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol. 2010.

- 11.Marschner IC, Collier AC, Coombs RW, et al. Use of changes in plasma levels of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA to assess the clinical benefit of antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 1998;177(1):40–7. doi: 10.1086/513823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palella FJ, Jr., Delaney KM, Moorman AC, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(13):853–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ray M, Logan R, Sterne JA, et al. The effect of combined antiretroviral therapy on the overall mortality of HIV-infected individuals. Aids. 2010;24(1):123–37. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283324283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Ledergerber B, et al. Long-term effectiveness of potent antiretroviral therapy in preventing AIDS and death: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2005;366(9483):378–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinz AJ, Fogler KA, Newcomb ME, et al. Problematic Alcohol Use Among Individuals with HIV: Relations with Everyday Memory Functioning and HIV Symptom Severity. AIDS Behav. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0602-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korthuis PT, Fiellin DA, McGinnis KA, et al. Unhealthy alcohol and illicit drug use are associated with decreased quality of HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(2):171–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826741aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conigliaro J, Gordon AJ, McGinnis KA, et al. How harmful is hazardous alcohol use and abuse in HIV infection: do health care providers know who is at risk? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(4):521–5. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahn JA, Samet JH. Alcohol and HIV disease progression: weighing the evidence. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7(4):226–33. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0060-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandiwana SK, Sebit MB, Latif AS, et al. Alcohol consumption in HIV-I infected persons: a study of immunological markers, Harare, Zimbabwe. Cent Afr J Med. 1999;45(11):303–8. doi: 10.4314/cajm.v45i11.8505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crum RM, Galai N, Cohn S, et al. Alcohol use and T-lymphocyte subsets among injection drug users with HIV-1 infection: a prospective analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20(2):364–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eskild A, Petersen G. Cigarette smoking and drinking of alcohol are not associated with rapid progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome among homosexual men in Norway. Scand J Soc Med. 1994;22(3):209–12. doi: 10.1177/140349489402200309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaslow RA, Blackwelder WC, Ostrow DG, et al. No evidence for a role of alcohol or other psychoactive drugs in accelerating immunodeficiency in HIV-1-positive individuals. A report from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Jama. 1989;261(23):3424–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Griensven GJ, de Vroome EM, de Wolf F, et al. Risk factors for progression of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among seroconverted and seropositive homosexual men. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(2):203–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veugelers PJ, Page KA, Tindall B, et al. Determinants of HIV disease progression among homosexual men registered in the Tricontinental Seroconverter Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140(8):747–58. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baum MK, Rafie C, Lai S, et al. Alcohol use accelerates HIV disease progression. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26(5):511–8. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chander G, Lau B, Moore RD. Hazardous alcohol use: a risk factor for non-adherence and lack of suppression in HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(4):411–7. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243121.44659.a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samet JH, Cheng DM, Libman H, et al. Alcohol consumption and HIV disease progression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(2):194–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318142aabb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu ES, Metzger DS, Lynch KG, et al. Association between alcohol use and HIV viral load. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(5):e129–30. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820dc1c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braithwaite RS, Bryant KJ. Influence of alcohol consumption on adherence to and toxicity of antiretroviral therapy and survival. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33(3):280–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, et al. A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112(3):178–93. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grodensky CA, Golin CE, Ochtera RD, et al. Systematic review: effect of alcohol intake on adherence to outpatient medication regimens for chronic diseases. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73(6):899–910. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ford N, Darder M, Spelman T, et al. Early adherence to antiretroviral medication as a predictor of long-term HIV virological suppression: five-year follow up of an observational cohort. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levison JH, Orrell C, Gallien S, et al. Virologic failure of protease inhibitor-based second-line antiretroviral therapy without resistance in a large HIV treatment program in South Africa. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daniel MD, Letvin NL, King NW, et al. Isolation of T-cell tropic HTLV-III-like retrovirus from macaques. Science. 1985;228(4704):1201–4. doi: 10.1126/science.3159089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanki PJ, McLane MF, King NW, Jr., et al. Serologic identification and characterization of a macaque T-lymphotropic retrovirus closely related to HTLV-III. Science. 1985;228(4704):1199–201. doi: 10.1126/science.3873705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Letvin NL. Animal models for AIDS. Immunology today. 1990;11(9):322–6. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90127-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gardner MB. The history of simian AIDS. J Med Primatol. 1996;25(3):148–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1996.tb00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Apetrei C, Kaur A, Lerche NW, et al. Molecular epidemiology of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsm in U.S. primate centers unravels the origin of SIVmac and SIVstm. J Virol. 2005;79(14):8991–9005. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.8991-9005.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphey-Corb M, Martin LN, Rangan SR, et al. Isolation of an HTLV-III-related retrovirus from macaques with simian AIDS and its possible origin in asymptomatic mangabeys. Nature. 1986;321(6068):435–7. doi: 10.1038/321435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chahroudi A, Bosinger SE, Vanderford TH, et al. Natural SIV hosts: showing AIDS the door. Science. 2012;335(6073):1188–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1217550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stone M, Keele BF, Ma ZM, et al. A limited number of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) env variants are transmitted to rhesus macaques vaginally inoculated with SIVmac251. J Virol. 2010;84(14):7083–95. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00481-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trichel AM, Roberts ED, Wilson LA, et al. SIV/DeltaB670 transmission across oral, colonic, and vaginal mucosae in the macaque. J Med Primatol. 1997;26(1-2):3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1997.tb00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amedee AM, Lacour N, Gierman JL, et al. Genotypic selection of simian immunodeficiency virus in macaque infants infected transplacentally. J Virol. 1995;69(12):7982–90. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7982-7990.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kestler H, Kodama T, Ringler D, et al. Induction of AIDS in rhesus monkeys by molecularly cloned simian immunodeficiency virus. Science. 1990;248(4959):1109–12. doi: 10.1126/science.2160735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirsch VM, Zack PM, Vogel AP, et al. Simian immunodeficiency virus infection of macaques: end-stage disease is characterized by widespread distribution of proviral DNA in tissues. J Infect Dis. 1991;163(5):976–88. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.5.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flaherty MT, Hauer DA, Mankowski JL, et al. Molecular and biological characterization of a neurovirulent molecular clone of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1997;71(8):5790–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5790-5798.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Z, Gettie A, Ho DD, et al. Primary SIVsm isolates use the CCR5 coreceptor from sooty mangabeys naturally infected in west Africa: a comparison of coreceptor usage of primary SIVsm, HIV-2, and SIVmac. Virology. 1998;246(1):113–24. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edinger AL, Amedee A, Miller K, et al. Differential utilization of CCR5 by macrophage and T cell tropic simian immunodeficiency virus strains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(8):4005–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y, Lou B, Lal RB, et al. Use of inhibitors to evaluate coreceptor usage by simian and simian/human immunodeficiency viruses and human immunodeficiency virus type 2 in primary cells. J Virol. 2000;74(15):6893–910. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.6893-6910.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luciw PA, Pratt-Lowe E, Shaw KE, et al. Persistent infection of rhesus macaques with T-cell-line-tropic and macrophage-tropic clones of simian/human immunodeficiency viruses (SHIV). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(16):7490–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reimann KA, Li JT, Veazey R, et al. A chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus expressing a primary patient human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate env causes an AIDS-like disease after in vivo passage in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996;70(10):6922–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6922-6928.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thippeshappa R, Ruan H, Kimata JT. Breaking Barriers to an AIDS Model with Macaque- Tropic HIV-1 Derivatives. Biology (Basel) 2012;1(2):134–64. doi: 10.3390/biology1020134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mumbauer A, Gettie A, Blanchard J, et al. Efficient mucosal transmissibility but limited pathogenicity of R5 SHIV SF162P3N in Chinese-origin rhesus macaques. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(5):496–504. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827f1c11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Del Prete GQ, Scarlotta M, Newman L, et al. Comparative characterization of transfection- and infection-derived simian immunodeficiency virus challenge stocks for in vivo nonhuman primate studies. J Virol. 2013;87(8):4584–95. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03507-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lopker M, Easlick J, Sterrett S, et al. Heterogeneity in neutralization sensitivities of viruses comprising the simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsmE660 isolate and vaccine challenge stock. J Virol. 2013;87(10):5477–92. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03419-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou Y, Bao R, Haigwood NL, et al. SIV Infection of rhesus macaques of Chinese origin: a suitable model for HIV infection in humans. Retrovirology. 2013;10(1):89. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ling B, Veazey RS, Luckay A, et al. SIV(mac) pathogenesis in rhesus macaques of Chinese and Indian origin compared with primary HIV infections in humans. Aids. 2002;16(11):1489–96. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200207260-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trichel AM, Rajakumar PA, Murphey-Corb M. Species-specific variation in SIV disease progression between Chinese and Indian subspecies of rhesus macaque. J Med Primatol. 2002;31(4-5):171–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0684.2002.02003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seman AL, Pewen WF, Fresh LF, et al. The replicative capacity of rhesus macaque peripheral blood mononuclear cells for simian immunodeficiency virus in vitro is predictive of the rate of progression to AIDS in vivo. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:2441–9. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-10-2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hirsch VM, Fuerst TR, Sutter G, et al. Patterns of viral replication correlate with outcome in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected macaques: effect of prior immunization with a trivalent SIV vaccine in modified vaccinia virus Ankara. J Virol. 1996;70(6):3741–52. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3741-3752.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Watson A, Ranchalis J, Travis B, et al. Plasma viremia in macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus: plasma viral load early in infection predicts survival. J Virol. 1997;71(1):284–90. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.284-290.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lewis MG, Bellah S, McKinnon K, et al. Titration and characterization of two rhesus-derived SIVmac challenge stocks. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10(2):213–20. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grant KA, Bennett AJ. Advances in nonhuman primate alcohol abuse and alcoholism research. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2003;100(3):235–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clark R, Polish E. Avoidance Conditioning and Alcohol Consumption in Rhesus Monkeys. Science. 1960;132(3421):223–4. doi: 10.1126/science.132.3421.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mello NK, Mendelso Jh. Factors Affecting Alcohol Consumption in Primates. Psychosom Med. 1966;28(4P2):529–&. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Deneau G, Yanagita T, Seevers MH. Self-administration of psychoactive substances by the monkey. Psychopharmacologia. 1969;16(1):30–48. doi: 10.1007/BF00405254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Karoly AJ, Winger G, Ikomi F, et al. The reinforcing property of ethanol in the rhesus monkey II. Some variables related to the maintenance of intravenous ethanol-reinforced responding. Psychopharmacology. 1978;58(1):19–25. doi: 10.1007/BF00426785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Winger GD, Woods JH. Reinforcing Property of Ethanol in Rhesus-Monkey .1. Initiation, Maintenance and Termination of Intravenous Ethanol-Reinforced Responding. Ann Ny Acad Sci. 1973 Apr 30;215:162–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1973.tb28263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Higley JD, Hasert MF, Suomi SJ, et al. Nonhuman primate model of alcohol abuse: effects of early experience, personality, and stress on alcohol consumption. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88(16):7261–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mello NK, Mendelson JH. Evaluation of a polydipsia technique to induce alcohol consumption in monkeys. Physiology & behavior. 1971;7(6):827–36. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(71)90047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grant KA, Johanson CE. The nature of the scheduled reinforcer and adjunctive drinking in nondeprived rhesus monkeys. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 1988;29(2):295–301. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grant KA, Johanson CE. Oral ethanol self-administration in free-feeding rhesus monkeys. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1988;12(6):780–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb01345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vivian JA, Green HL, Young JE, et al. Induction and maintenance of ethanol self-administration in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis): long-term characterization of sex and individual differences. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(8):1087–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grant KA, Leng X, Green HL, et al. Drinking typography established by scheduled induction predicts chronic heavy drinking in a monkey model of ethanol self-administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(10):1824–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00765.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cheng HJ, Grant KA, Han QH, et al. Up-regulation and functional effect of cardiac beta3-adrenoreceptors in alcoholic monkeys. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(7):1171–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Burnett EJ, Davenport AT, Grant KA, et al. The effects of chronic ethanol self- administration on hippocampal serotonin transporter density in monkeys. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:38. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kroenke CD, Flory GS, Park B, et al. Chronic Ethanol (EtOH) Consumption Differentially Alters Gray and White Matter EtOH Methyl (1) H Magnetic Resonance Intensity in the Primate Brain. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(8):1325–32. doi: 10.1111/acer.12097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Katner SN, Flynn CT, Von Huben SN, et al. Controlled and behaviorally relevant levels of oral ethanol intake in rhesus macaques using a flavorant-fade procedure. Alcoholism-Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28(6):873–83. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128895.99379.8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kumar R, Perez-Casanova AE, Tirado G, et al. Increased viral replication in simian immunodeficiency virus/simian-HIV-infected macaques with self-administering model of chronic alcohol consumption. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39(4):386–90. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000164517.01293.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Marcondes MC, Watry D, Zandonatti M, et al. Chronic alcohol consumption generates a vulnerable immune environment during early SIV infection in rhesus macaques. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(9):1583–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bagby GJ, Stoltz DA, Zhang P, et al. The effect of chronic binge ethanol consumption on the primary stage of SIV infection in rhesus macaques. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(3):495–502. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000057947.57330.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Winsauer PJ, Moerschbaecher JM, Brauner IN, et al. Alcohol unmasks simian immunodeficiency virus-induced cognitive impairments in rhesus monkeys. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(12):1846–57. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000042171.80435.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bagby GJ, Zhang P, Purcell JE, et al. Chronic binge ethanol consumption accelerates progression of simian immunodeficiency virus disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(10):1781–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nelson S, Bagby GJ. Alcohol and HIV Infection. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2011;122:244–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Poonia B, Nelson S, Bagby GJ, et al. Intestinal lymphocyte subsets and turnover are affected by chronic alcohol consumption: implications for SIV/HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(5):537–47. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000209907.43244.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mangili A, Murman DH, Zampini AM, et al. Nutrition and HIV infection: review of weight loss and wasting in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy from the nutrition for healthy living cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(6):836–42. doi: 10.1086/500398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tang AM, Forrester J, Spiegelman D, et al. Weight loss and survival in HIV-positive patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(2):230–6. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200210010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wanke CA, Silva M, Knox TA, et al. Weight loss and wasting remain common complications in individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(3):803–5. doi: 10.1086/314027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Haller RG, Knochel JP. Skeletal muscle disease in alcoholism. Med Clin North Am. 1984;68(1):91–103. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)31243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Molina PE, McNurlan M, Rathmacher J, et al. Chronic alcohol accentuates nutritional, metabolic, and immune alterations during asymptomatic simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(12):2065–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Molina PE, Lang CH, McNurlan M, et al. Chronic alcohol accentuates simian acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated wasting. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(1):138–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bonnet F, Amieva H, Marquant F, et al. Cognitive disorders in HIV-infected patients: are they HIV-related? Aids. 2013;27(3):391–400. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835b1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr., et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75(23):2087–96. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pumpradit W, Ananworanich J, Lolak S, et al. Neurocognitive impairment and psychiatric comorbidity in well-controlled human immunodeficiency virus-infected Thais from the 2NN Cohort Study. Journal of neurovirology. 2010;16(1):76–82. doi: 10.3109/13550280903493914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Robertson KR, Smurzynski M, Parsons TD, et al. The prevalence and incidence of neurocognitive impairment in the HAART era. Aids. 2007;21(14):1915–21. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32828e4e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni JM, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in HIV patients despite long-standing suppression of viremia. Aids. 2010;24(9):1243–50. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283354a7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vivithanaporn P, Heo G, Gamble J, et al. Neurologic disease burden in treated HIV/AIDS predicts survival: a population-based study. Neurology. 2010;75(13):1150–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f4d5bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Persidsky Y, Ho W, Ramirez SH, et al. HIV-1 infection and alcohol abuse: neurocognitive impairment, mechanisms of neurodegeneration and therapeutic interventions. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2011;25(Suppl 1):S61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rothlind JC, Greenfield TM, Bruce AV, et al. Heavy alcohol consumption in individuals with HIV infection: effects on neuropsychological performance. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS. 2005;11(1):70–83. doi: 10.1017/S1355617705050095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Brenchley JM, Schacker TW, Ruff LE, et al. CD4+ T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract. J Exp Med. 2004;200(6):749–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mehandru S, Poles MA, Tenner-Racz K, et al. Primary HIV-1 infection is associated with preferential depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes from effector sites in the gastrointestinal tract. J Exp Med. 2004;200(6):761–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Veazey RS, DeMaria M, Chalifoux LV, et al. Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science. 1998;280(5362):427–31. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Banan A, Choudhary S, Zhang Y, et al. Ethanol-induced barrier dysfunction and its prevention by growth factors in human intestinal monolayers: evidence for oxidative and cytoskeletal mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291(3):1075–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Elamin E, Jonkers D, Juuti-Uusitalo K, et al. Effects of ethanol and acetaldehyde on tight junction integrity: in vitro study in a three dimensional intestinal epithelial cell culture model. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ma TY, Nguyen D, Bui V, et al. Ethanol modulation of intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(4 Pt 1):G965–74. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.4.G965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Poonia B, Nelson S, Bagby GJ, et al. Chronic alcohol consumption results in higher simian immunodeficiency virus replication in mucosally inoculated rhesus macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22(6):589–94. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Morris A, Crothers K, Beck JM, et al. An official ATS workshop report: Emerging issues and current controversies in HIV-associated pulmonary diseases. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8(1):17–26. doi: 10.1513/pats.2009-047WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Morris A, Lundgren JD, Masur H, et al. Current epidemiology of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(10):1713–20. doi: 10.3201/eid1010.030985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Siemieniuk RA, Gregson DB, Gill MJ. The persisting burden of invasive pneumococcal disease in HIV patients: an observational cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:314. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Koziel H, Kim S, Reardon C, et al. Enhanced in vivo human immunodeficiency virus-1 replication in the lungs of human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons with Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(6):2048–55. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.6.9902099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nuorti JP, Butler JC, Gelling L, et al. Epidemiologic relation between HIV and invasive pneumococcal disease in San Francisco County, California. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(3):182–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-3-200002010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Magnenat JL, Nicod LP, Auckenthaler R, et al. Mode of presentation and diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144(4):917–22. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.4.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nelson S, Happel KI, Zhang P, et al. Effect of Bacterial Pneumonia on Lung Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV) Replication in Alcohol Consuming SIV-Infected Rhesus Macaques. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013 doi: 10.1111/acer.12070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rennard BO, Ertl RF, Gossman GL, et al. Chicken soup inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis in vitro. Chest. 2000;118(4):1150–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.4.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yamamoto H, Matano T. Anti-HIV adaptive immunity: determinants for viral persistence. Reviews in medical virology. 2008;18(5):293–303. doi: 10.1002/rmv.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pahar B, Amedee AM, Thomas J, et al. Effects of alcohol consumption on antigen-specific cellular and humoral immune responses to SIV in rhesus macaques. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829f6dca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]