Abstract

Objectives

To describe older smokers’ perceptions of risks and use of e-cigarettes, and their responses to marketing and knowledge of, and opinions about, regulation of e-cigarettes.

Methods

Eight 90-minute focus groups with 8 to 9 participants met in urban and suburban California to discuss topics related to cigarettes and alternative tobacco products.

Results

Older adults are using e-cigarettes for cessation and as a way to circumvent no-smoking policies; they have false perceptions about the effectiveness and safety of e-cigarettes. They perceive e-cigarette marketing as a way to renormalize smoking.

Conclusions

To stem the current epidemic of nicotine addiction, the FDA must take immediate action because e-cigarette advertising promotes dual use and may contribute to the renormalization of smoking.

Keywords: older smokers, e-cigarettes, marketing, perception, use

There is an upsurge in tobacco industry advertising to encourage cigarette smokers to use electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) in no-smoking areas and as an aid to smoking cessation. E-cigarettes are devices that include a battery-powered heating element designed to heat and aerosolize liquids containing varying levels of nicotine, flavoring agents, a number of unknown components, and in some cases tobacco itself.1 Aerosolized nicotine in e-cigarettes contains glycerine to mimic smoke of conventional cigarettes while supposedly delivering lower toxin levels than those found in a conventional cigarette.2–5 Vaporizers (or vape-pens) are similar to e-cigarettes, but typically contain a larger battery with variable heat settings to heat a refillable tank with a wick for liquid nicotine or a compartment for vaporizing THC oil or even cannabis buds. Vaporizers are more expensive than e-cigarettes, and their higher heat levels can deliver a larger dose of nicotine vapor. The nicotine can be purchased in varying concentrations and flavors. There is a dearth of information on the perceptions and use of e-cigarettes among older adults.

Prevalence and Impact of Smoking in Older Adults

Older smokers initiated smoking when it was ubiquitous and they were most impacted by indoor smoking bans. Disparities in tobacco use among adults continue to exist by race/ethnicity, education, income, and mental health status.6 In the last decade, smoking prevalence has declined in all age groups in the US except for older smokers. In fact, smoking prevalence for adults over 65 actually has increased. In 2011, smoking prevalence for 45–64 year-olds was 19.5%, higher than the national average of 18%.7 These statistics reflect both the marginalization of older smokers by society and tobacco research funding,8 and the fact that older smokers are targeted by an aggressive tobacco industry.9 Older smokers frequently face economic and social disadvantages; yet, they are often ignored in discussions of marginalized populations impacted by tobacco.10–13

Because older smokers underestimate both the risks of smoking and the benefits of cessation, they are the least likely to quit of any age group.13 Older adults have the greatest smoking related health burden.14 However, quitting smoking, at any age, decreases cardiovascular risk and provides significant health benefits and quitting by age 50 reduces the risk of lung cancer by half.15 Yet, older adults (45–64 year-olds) are often unaware of these benefits.16 A primary reason for these misperceptions is the tobacco industry’s aggressive targeting of older smokers8 in the marketing of both conventional and emerging tobacco products, such as e-cigarettes and vaporizers.17–19 Tobacco companies encourage tobacco use through marketing that reduces perceptions of harm associated with tobacco use and increases perceptions of social acceptability.20–22 Previous analyses have shown that the tobacco industry has targeted older adults and marketed “light” and “low-tar” cigarettes as alternatives to quitting with the false implication that they were healthier choices.8 Using a similar strategy, the tobacco industry has expanded its advertising of smokeless tobacco and e-cigarettes as alternative products for use in no-smoking areas and as aides to decrease smoking.23,24

The Emergence of E-cigarette Use in Older Adults

In the US, the prevalence of e-cigarette use is rising; in one study, 3.3% of adults in 2010 and 6.2% in 2011 had ever used an e-cigarette.25 In addition, awareness of these products among adults increased from 40.9% in 2010 to 57.9% in 2011.25 Current cigarette smokers are more likely to use e-cigarettes than former or never smokers25 and in 2012, 76.3% of current e-cigarette users reported concurrent use of conventional cigarettes.26–29

There has been a dramatic increase in the sales of alternative tobacco and nicotine products (eg, smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes, SNUS, snuff, chew, etc.) in California over the past 10 years, from $77.1 million in 2001 to $210.9 million in 2011.30 Whereas the use of smokeless products is higher in younger populations, California adults using e-cigarettes in the past 30 days doubled from 1.8% in 2012 to 3.5% in 2013.25,30 Former and current smokers are more likely to be aware of and use e-cigarettes than never smokers.25

Research indicates that exposure to tobacco industry marketing distorts perceptions about the availability, use, and risks of tobacco.31 Despite the importance of risk and benefit perceptions in decisions to use tobacco products,32 most research has focused on adolescents or a general smoking sample, and has concentrated only on conventional cigarette use.33,34 How older adults’ perceptions of e-cigarettes affect their tobacco use patterns (eg, initiation, re-initiation, continuation, cessation, product switching, dual use) is unknown.

E-cigarettes are marketed throughout the world as both a smokeless and safe alternative to conventional cigarettes, and as an aid for smoking cessation.35,36 Companies are marketing e-cigarettes as smoking cessation aids (Figure 1),36–39 and in response to these messages, some studies with significant numbers of participants over the age of 45 found that many people use e-cigarettes to try to stop smoking.27,41–43 In a 2013 study, among the 765 state quit line callers who had ever used e-cigarettes, the most reported reason for use was to help quit other tobacco (51.3%).43

Figure 1.

Electronic Cigarette Blog Promotes E-cigarettes as Smoking Cessation Devices

Note.

Available at: http://newhere.com/blog/quit-smoking-electronic-cigarettes/. Accessed May 31, 2014.

E-cigarette Marketing and Renormalization of Smoking

Seeing the emergence of a multi-billion dollar market, the tobacco industry has invested heavily in e-cigarette production and marketing.44 Due to the lack of regulations over the marketing of e-cigarettes, the tobacco industry has revived television and radio marketing strategies, media channels that have been banned for more than 4 decades.40 A major public health concern is that, given the growing tobacco industry market share, e-cigarettes will be marketed on television, radio, and the Internet in ways that ultimately renormalizes smoking of conventional cigarettes.38

Currently, there has been a resurgence in tobacco industry advertising to encourage cigarette smokers to use e-cigarettes in no-smoking areas and as an aid to quit tobacco cigarettes.23,24 Studies have demonstrated for decades that exposure to cigarette advertising is linked to smoking.45,46 E-cigarette advertisements are challenging a barrier to television promotion that has been in place for over 40 years. E-cigarettes mimic the personal experience and public performance of smoking, and marketing campaigns threaten to reverse the successful, decades-long public health campaign to denormalize smoking.47 Messages that renormalize smoking in public places are likely to appeal to older smokers who initiated smoking when it was ubiquitous and were, therefore, most impacted by bans on advertising and smoking indoors. Most research on tobacco marketing, risk perception, and smoking behavior has been done with adolescents and young adults who have not experienced tobacco advertising on television and were not alive when smoking was socially acceptable.

E-cigarette Regulation

Only a few state and local e-cigarette regulations exist. Although the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not currently regulate e-cigarettes, they have proposed to deem e-cigarettes as a tobacco product.48 The proposed rules will ban selling e-cigarettes to minors. It will not, however, ban Internet sales. Confusion about whether or not e-cigarettes are regulated has been documented among young adults49,50 and no data are available for adults.

Although current public health efforts to promote regulation of e-cigarettes is currently focused on youth,50–54 marketing messages that renormalize smoking in public places are likely to appeal to older smokers.31,55,56 The aims of this study were to: describe older smokers’ use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), characterize their perceptions of the risks and benefits associated with e-cigarettes, explore responses to marketing related to e-cigarettes, and describe older adults’ knowledge of, and opinions about, regulation of e-cigarettes.

METHODS

This focus group study was the first phase of a larger project to describe and understand the behaviors, perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs associated with tobacco use (ie, conventional and new and emerging tobacco products) among older smokers (≥ 45 year old), especially dual users. For this study, 8–9 participants in 8 focus groups lasting 90-minutes each met in urban and suburban California to discuss topics related to cigarettes and alternative tobacco products.

Participants were recruited using flyers and online classified advertisements. The study focused on smokers in California because of the state’s relatively low smoking prevalence and longstanding clean indoor air law.57 These laws have created an ideal climate for aggressive promotion of smokeless tobacco products and e-cigarettes to be used in smoke-free environments. Inclusion criteria consisted of being: 45 years of age or older, a current smoker or one who quit within the last 2 years, able to speak English, able to read at the fifth grade level, without sight or hearing impairment, and able to tolerate a group session of 90 minutes duration. Participants provided informed consent for the study and audio recording, and completed a demographic questionnaire that included tobacco use history.

The groups were led by 2 members of the research team in a leased community space. The focus group discussions were semi-structured in which participants were open to explore other topics as they emerged in the discussion. Participants were asked to discuss their current tobacco use, current interest in quitting, and the places and situations in which they avoid smoking or use alternative tobacco products (Table 1). Participants were shown pictures and definitions of alternative tobacco products including e-cigarettes, snus, chew, and dissolvables to elicit their perceptions of the benefits and risks of alternative tobacco products, and to understand past and future use and future intentions to use such products. Participants were asked to describe where they remembered seeing tobacco marketing. Participants were then shown ads for e-cigarettes to elicit emotional reactions to the ads, their perceptions of the advertisement’s intended audience, and effectiveness in influencing conventional and e-cigarette use. At completion of the group, participants received a $40 gift card to a local department store.

Table 1.

Focus Group Interview Guide

|

Data Analysis

A professional transcriptionist who was instructed to label each speaker turn as a separate paragraph transcribed the focus groups. Within Microsoft Word, we used the “convert text to table function” to convert the transcripts into a continuous vertical table of cells with each cell containing one speaker turn. We then pasted these tables into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, adding columns identifying the date and location of the focus group, and numbering each speaker turn, or cell row. Thus, each speaker turn provided a unit of analysis for the application of codes varying in size from a single word to several paragraphs. To code these segments we created a column for each code, and indicated the presence of the code by adding the coder’s initials to the intersection of the segment row and the code column.

This spreadsheet enabled us to view the data segments and the codes applied to them easily and in analytically useful ways. First, the transcripts were read in their original, sequential context. The segments were indexed into topical codes enabling us to see horizontal patterns in the co-occurrence of topics for each data segment. An initial 53 topical codes were identified from the transcripts, and through discussions among the 3 coders, the code list was reduced iteratively to 42 as we combined topical codes having significant overlap (Table 2). By using their initials when coding segments, coders were able to identify and discuss discrepancies in how each coder applied codes to each data segment until we reached agreement.

Table 2.

Topical Codes

| Code Category |

Code | Speaker Turns Coded |

|---|---|---|

| Cessation | Doctor Interaction | 88 |

| Cessation | Successful Quit Attempt | 63 |

| Cessation | Other Quit Methods | 47 |

| Cessation | Unsuccessful Quit Attempt | 43 |

| Cessation | Patch | 28 |

| Cessation | Chantix | 21 |

| Cessation | Fatalism | 8 |

| Cessation | Not Currently Smoking | 7 |

| Cessation | Wellbutrin | 6 |

| Consequences | Health Effects | 110 |

| Consequences | Lung Cancer | 75 |

| Consequences | Addiction | 67 |

| Consequences | Smell Bothersome | 63 |

| Consequences | Second Hand Smoke | 29 |

| Consequences | Cosmetic Effects | 3 |

| Contexts | Nostalgia | 147 |

| Contexts | Sex | 50 |

| Contexts | Pot | 48 |

| Contexts | Movies/Tv | 47 |

| Contexts | Like About Smoking | 32 |

| Contexts | Social Triggers | 32 |

| Contexts | Sport | 28 |

| Contexts | Alcohol | 21 |

| Contexts | Class | 19 |

| Contexts | Casino | 18 |

| Contexts | Stress | 15 |

| Contexts | Weight Control | 1 |

| Policy | Ads Seen | 336 |

| Policy | Warnings Impactful | 219 |

| Policy | Smoking Ban | 171 |

| Policy | Warnings Not Impactful | 130 |

| Policy | FDA | 100 |

| Policy | E Cig Ban | 72 |

| Policy | Tob Regulation | 69 |

| Policy | Taxes | 39 |

| Policy | Lung Cancer Screening | 28 |

| Policy | Price | 12 |

| Products | E-Cig | 558 |

| Products | Chew | 125 |

| Products | Cigars | 89 |

| Products | Strips/Orbs | 70 |

| Products | Snus | 60 |

| Products | Additives | 37 |

| Products | Brand Loyalty | 26 |

| Products | Menthol | 25 |

| Products | Nicotine | 20 |

When analyzing themes across segments on a particular topic, we sorted rows by code to create collections of segments by topic of discussion. Finally, to ensure that we included all relevant segments in a collection, we searched for specific key terms (eg, nicotine, vape, ban, etc) across the focus group transcripts, and in this way, updated the coding until we were satisfied that transcripts had been coded adequately. Finally, we were able to refine our collections by sorting the spreadsheet by combinations of codes, eg, “nostalgia” and “ads effective.” The present paper focused on segments coded as related to e-cigarettes, marketing, and regulation.

RESULTS

The sample included 52 current and former smokers, ages 45 to 68 (mean age 52.6 years; SD 6.1). Forty-seven (90.4%) of the participants were current cigarette smokers and 37 (71%) were male and 29 (58%) had an annual income of >40,000 USD. Ethnicity/racial identification included 26 (50%) White, 17 (33%) Black, and 9 (17%) identified as other; 43 (83%) had at least some college.

Use of E-cigarettes as a Cessation Aid

Although not all smokers in the focus groups had tried e-cigarettes, all reported that they were familiar with them and had seen advertising for e-cigarettes, and many planned to try them. Participants were not asked specifically about vaporizers but they made the distinction that e-cigarettes are “for nicotine only” and look like “real cigarettes” and vaporizers “can use liquids other than nicotine” and “look less like a cigarette” and “the flavors are to attract kids.”

Several participants stated that they did not know anyone who had successfully quit smoking with the use of e-cigarettes. However, when asked about intention, many said they could see using them in the near future either as an attempt to quit or for dual use:

“…using one of those to quit smoking…I do not know anybody that has done that. They just use it when they’re in doors. But they’re not quitting smoking. As soon as they go outside, they’re smoking regular cigarettes.”

“I think the e-cigarettes were supposed… to help someone quit. They have more nicotine than the regular packs of cigarettes. [So] it’s just to use… in places that you’re not allowed to smoke.”

“…my friend…he’s trying to quit …he’ll smoke one of those e-cigarettes for a couple months and then pick up a pack of cigarettes…And then he’ll be back on the e-cigarette the next couple of days. So…he’s been smoking both of them for about 2 years I think. So, I don’t see people stopping really.”

Although older smokers seem to be embracing e-cigarettes, they remain cynical about the health benefits and consequences. The following is an exchange among participants:

“I distrust advertising in general, and corporate scumbags who are trying to sell us whatever product it is you consume that’s bad for us - just makes these things seem like lies to me. I’m not exactly sure what they’re trying to sell, other than that you can beat the smoking ordinances in your local city. I guess I had a misconception that they were selling them to quit smoking. It actually says, ‘Why quit?’ But, yeah, these are terrible. I’m not sure if this product is any healthier than cigarettes - maybe a little bit. But I distrust it.”

“Now, I don’t really believe anything the tobacco company says …I don’t know what’s in them [e-cigarettes], but something is in there to make you addicted…”

“I agree, 100%. Yeah, it could be nuclear waste for all they care.”

Flavors

Older adults did not express an interest in flavors (other than tobacco flavor) for e-cigarettes; they consistently associated flavors with youth and children:

“…the flavors are to attract kids”

“Well, I tried the e-cigarettes… but they just haven’t captured or been able to manufacture a flavor of a real cigarette.”

“I’m kind of talking about the ones that don’t have flavor, that are, like, a waterless vapor that have no odor…A lot of the kids are doing the ones with the flavors…[like] blueberry, I see… more girls using them than guys, …especially, you know, the flavored ones…”

“I think it’s also a risk where if somebody look[s] at it and think[s] oh it’s the cool thing. But they’re not a smoker currently. I hate using that term pathway but it can easily move them over to - a pack of cigarettes is $5 and one of these [e-cigarettes] is $12. …They’re changing the flavors on them too … to get high school kids.”

Perceived Benefits of E-cigarettes

Discussions often returned to the topic of past failed smoking cessation attempts and the hope that e-cigarettes might be the answer “the thing that finally works.” Even though none of the participants had quit smoking with e-cigarettes, or even knew someone who had quit, many still saw e-cigarettes as a viable choice for smoking cessation:

“Well, I haven’t tried them yet, but I think that the next time I quit that I will probably try them because I have friends who have tried them...”

A cited benefit was cost:

“…they are cheaper than other cessation aids”

and

“those e-cigarettes, they’re like 30 bucks a piece…but anything [else] that helps you quit is really, really expensive.”

Healthier alternative to cigarettes

Generally, participants agreed that e-cigarette advertisements promoted the perception that e-cigarettes are less risky than conventional cigarettes. The lack of government warnings about e-cigarettes was seen as an endorsement of the claim that they are a healthier alternative to cigarettes.

“I mean there was one that I saw, oh no tar. So, people think oh I can be safer with this…a healthy alternative to smoking real cigarettes…. I see that advertising too where they try to say it’s a healthy alternative.”

“Well from the ads …I don’t see many warnings at all. It’s almost like they were saying …this is the pleasurable thing to do. Have a good time. … I didn’t see any warnings.”

For use in no-smoking areas

The perception that they could be used anywhere, regardless of smoke-free policies, was described as a major advantage to e-cigarettes:

“I thought they were a great idea, because you can do it at work. You can do it anywhere…so that really pushed me further to want to investigate it more.”

Another participant agreed:

“If you’re somewhere you’re going to be for a long time you know you can’t smoke. I think…these would be a substitute for a cigarette. So, it would help you with the no-smoking rules.”

Smoking with social acceptance and no second hand smoke

The use of e-cigarettes was seen as a way to continue smoking, or at least have the tactile experience of smoking, without being socially isolated, because there is “no smell” and “no second hand smoke.” One participant described how e-cigarettes helped her regain the feeling of inclusion in discussions with other smokers:

“I could still be a part of the community, [when I quit] conversations happened outside with the people who were smoking, and many of them were people that I love dearly and I wasn’t a part of those [conversations].”

Perceived Risks/Disadvantages of E-cigarettes

The perceived risks and disadvantages of e-cigarettes were mostly related to the unknown nature of e-cigarettes and included the lack of scientific evidence about safety, unknown levels of nicotine with a question of satisfaction, and possible dangers such as volatility (ie, explosions) and physical reactions.

Lack of scientific evidence

There was a general consensus that e-cigarettes were appealing despite uncertainties:

“It’s kind of scary, because they’re a new product, and it’s hard to know, you know, if it’s worse for you than cigarettes actually are…I’m not sure. I think they just haven’t done enough studies on the use of those to see if they hurt you or not”

and

“You don’t know what’s in it…but there are chemicals in the reaction…They don’t have to tell you. So, you don’t know what those chemicals are.”

Unknown levels of nicotine

Everyone was aware that e-cigarettes had nicotine but they did not like that they were unable to gauge how much nicotine exposure they were receiving and they complained of lack of satisfaction.

“…I’m not able to tell how many cigarettes I’m smoking, you know…if I smoke on these for 5 minutes, then [have] I had one cigarette? …I don’t want to smoke 5 in a row. I just want to smoke one cigarette.”

Mechanical dangers

All participants had heard or seen news reports of e-cigarette mechanical dangers that included mishaps and explosions:

“Well, it’s not tobacco that you’re smoking. No harmful tobacco in your lungs, but they blow up every once in a while,”

and referring to a different report,

“… their jaw came off and he blew up his nose too…I’d rather smoke than have my face blown off.”

Comparative cost with conventional cigarettes

Although e-cigarettes are advertised as less expensive than conventional cigarettes, there was confusion about their cost-effectiveness. Whereas some perceived e-cigarettes as expensive,

“Those e-cigarettes, they’re like 30 bucks a piece…”

“…it’s expensive…Yeah because one is like $11,”

and

“They run out. You’ve got to keep buying them right? You have the main cigarette and then there’s a little …filtered part is what you have to keep buying and they’re like 10 bucks for like 5 of 6 cartridges.”

Others perceived e-cigarettes as less expensive than conventional cigarettes:

“So, one cartridge a day is about $2 a day, so it’s a lot cheaper. So, it’d be 14 bucks a week, 7 days a week.”

This discrepancy was present among all focus groups.

E-cigarette Marketing and Vaporizers

Participants were not asked specifically about vaporizers but they made the distinction that e-cigarettes are “for nicotine only” and look like “real cigarettes” and vaporizers “can use liquids other than nicotine” and “look less like a cigarette” and “the flavors are to attract kids.”

Anybody, everybody is using them [vaporizers]

Participants spoke of wide spread use of vaporizers among older adults:

“A lot of people, over 45 have them. … you can put whatever you want in them…You can buy a big jug of nicotine oil… They’re so popular.”

[Moderator asked: ‘Younger people do these things?’] “No, anybody, everybody.”

Renormalization of Smoking

There was a consensus that e-cigarette advertising promoted dual use of conventional tobacco products and electronic smoking because the products look similar in appearance. There was almost unanimous agreement that the current e-cigarette advertisements contributed to the renormalization of smoking because images are nearly indistinguishable from conventional cigarettes and the ads promoted smoking as a socially desirable behavior:

“It’s making smoking normal again…” and “Like, they’re not trying to get you to quit -- in fact, they’re trying to encourage you …so you smoke more…”

The appeal of nostalgia as a marketing tool

Participants discussed the nostalgic tone of the e-cigarette ads and how they reminded them of ad campaigns of their youth featuring bowling alleys and nightclubs.

“…definitely [targeted for] a more mature crowd because you have…Hennessy or brandy… that’s something -- a more mature crowd would probably consume. And the pack, it’s like… the Marlboro man had.”

“Like… when it was okay to smoke everywhere, it’s like they took the same campaigns and put an ‘E’ in front of the cigarette. Okay, we’re starting all over again. Same people, same campaigns, just put an ‘E’ in front of it and it’s okay. But these pictures are almost identical [to those] they used back in the ‘70s.”

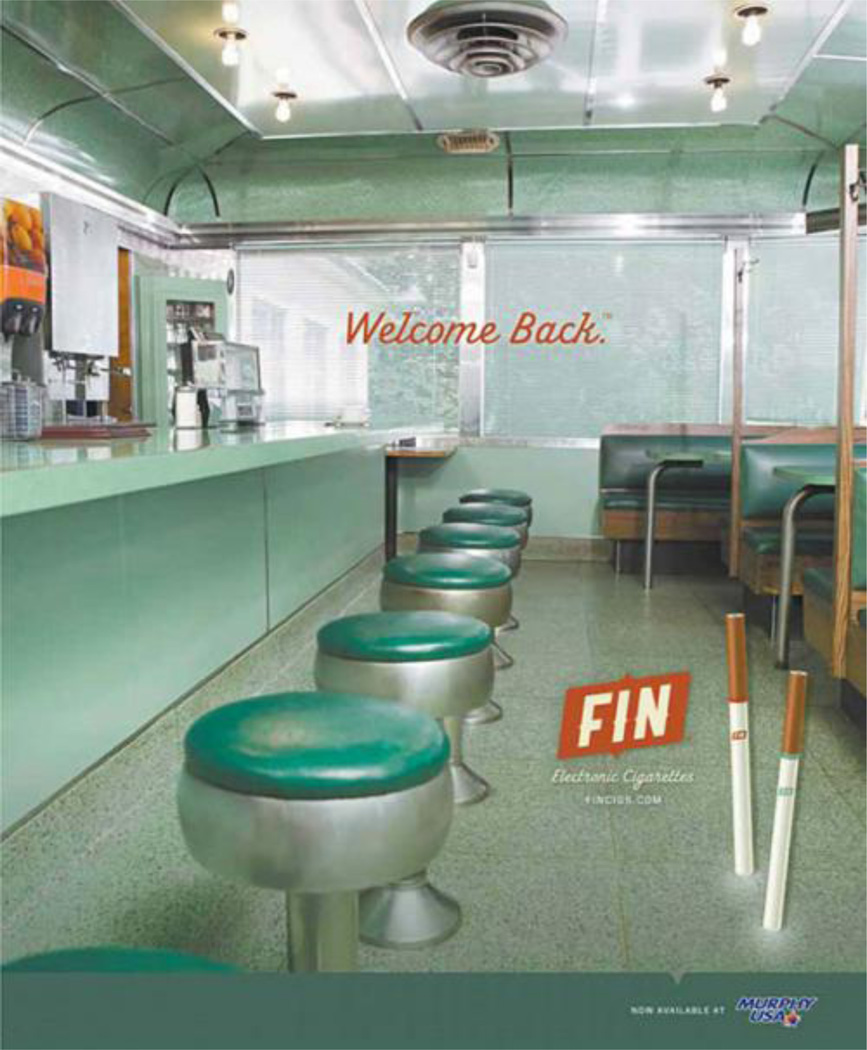

The nostalgic appeal of the ads to older smokers is exemplified by the Fin (an e-cig company) tag line: “Welcome Back” with pictures of mid-century diners and living room interiors photographed from a child’s perspective (Figure 2).

“… [for] people who may have quit, these ideas are sort of like a comfortable environment of the days of past are here again…”

Figure 2.

E-cigarette Ad with the Slogan “Welcome Back,” Depicting a Diner with a 1960s’ Décor Shot at the Vantage Point of a 2nd-grader, Suggesting they Might be Targeting People Who were ~7 years Old circa 1964

Note.

Available at: www.trinketsandtrash.org.

Accessed May 31, 2014.

Participants described their surprise in seeing e-cigarette ads appear on cable television. By deploying their ads on television, e-cigarette marketers are effectively tapping into the nostalgia of our focus group participants who reminisced with each other by repeating the tag lines and jingles of cigarette ads from the 1960s and 1970s.

Participants recalled a time before warning labels and advertising restrictions on tobacco products. The reminiscence provided them with a historical view of the ways that the industry has adapted its marketing tactics over the decades. Distrust of the tobacco industry was expressed:

“I think it’s the big tobacco companies behind e-cigs. I think they’re trying to cover every base they can.”

Regulation of E-cigarettes

Several discussions addressed the lack of warning labels and confusion about the legal status of e-cigarettes, opinions differed about the need for e-cigarette regulation.

“Well from the ads I can see compared to the old cigarette Surgeon General warning I don’t see many warnings at all. It’s almost like they were saying about this particular guy with the e-cigarette, this is the pleasurable thing to do. Have a good time. Don’t worry about people seeing you smoke. I didn’t see any warnings.”

There was confusion about age limits and whether e-cigarettes were banned:

“Yes, I believe you have to be 18…you do have to show ID. For the Blu ones…I don’t know about the other ones.”

“…I think I saw about them legislating a law for e-cigarettes”

and

“…as far as regulation, if it says cigarette on it they regulate it. But if it’s just a vaporizer, even if it’s filled with tobacco or nicotine, anybody can buy it as long as it doesn’t say cigarette on it.”

DISCUSSION

This is the first study known to provide insight into risk and benefit perceptions of older adults related to the use of e-cigarettes. Our results suggest that older adults are interested in e-cigarettes and vaporizers and they are using them in increasing numbers as a cessation aid and as a way to circumvent no-smoking policies. Older smokers were unclear about the effectiveness, safety and risk, or benefits of e-cigarettes, likely due to misleading advertising.

Some ads target older adults and highlight the possible health benefits of e-cigarettes; some even suggest that e-cigarettes may prevent Alzheimer’s Disease (Figure 3). Some participants believed that e-cigarette advertising promoted e-cigarettes as being beneficial for health. Many were hopeful but they were also skeptical about the benefits and safety of e-cigarettes. There was almost unanimous agreement that current e-cigarette advertising promoted use of cigarettes to circumvent no-smoking laws and that the images used contributed to the renormalization of smoking.

Figure 3.

Could E-cigarettes Someday be Used to Combat Alzheimer’s Disease?

Note.

Available at: http://spinfuel.com/vaping-news/?s=Alzheimer.

Accessed October 31, 2014.

The limitations of this study are inherent to qualitative methodology. This study was designed to be a first step toward characterizing e-cigarette use and risk perceptions among older adults. Although important, it is unknown if the identified themes are relevant to all older smokers or are just findings relayed by an older audience. Because of the design, sample size, and the geographical limitation, the results are not generalizable.

Further studies are needed. Because of smoking prevalence in this group, and the extended time between initiation of smoking and appearance of disease, older adults are disproportionately affected by tobacco related diseases. Older smokers’ perceptions of e-cigarette marketing reflect their formative smoking experiences and their perceptions of the experiences of others. Therefore, older adults’ perceptions differ from ones of younger cohorts, making this an important population to be studied in relation to risk and benefit perceptions and use of e-cigarettes. A larger national quantitative survey study is indicated. In addition, randomized control trials with large samples are needed to determine if e-cigarettes are an effective cessation aid or an ultimate deterrent from quitting.

Relapse is a salient feature of nicotine addiction and most older smokers have a long history of smoking cessation attempts and failures.57 They have tried various cessation aids, and e-cigarettes present as the latest hope for smoking cessation. However, a tension exists between hoping for a successful cessation aid and having lived through the experience of being “duped” by the tobacco industry – many older smokers started smoking before the harms were publically exposed. Therefore, although older smokers seem to be embracing e-cigarettes, they remain cynical about the health benefits and consequences.

Our results add support to previous findings that older adults are not experiencing successful cessation with e-cigarettes. Despite tobacco industry marketing messages asserting that e-cigarettes are effective cessation aids, in a proposed deeming rule, the FDA stated: “There is no evidence to date that e-cigarettes are effective cessation devices.”43 A meta-analysis of 5 population studies found significantly lower odds of quitting (OR = 0.61, 95% CI 0.45–0.83) among adult smokers who had used e-cigarettes, compared to those who had not.44 Older adults may perceive marketing messages differently than younger smokers who are not subject to the same nostalgia and cynicism. The anachronistic imagery and use of previously banned media such as television, make e-cigarette ads especially salient for older smokers who remember the days when smoking and cigarette advertising were ubiquitous and unrestricted. Like “low-tar” cigarettes, e-cigarettes are similarly marketed to older smokers as a healthier alternative to conventional cigarettes. One systematic content analysis of e-cigarette website marketing found that 95% of the websites made explicit or implicit health-related claims and 64% had a smoking cessation claim.40

Our findings demonstrate the confusion expressed by older smokers about regulation of e-cigarettes. One reason for this may be that some e-cigarette products erroneously bear the FDA label (Figure 4). Whereas the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act explicitly prohibits use of “FDA-approved” language for marketing of tobacco products, this restriction currently does not apply to e-cigarettes.

Figure 4.

E-cigarette Liquid Refill Bearing the FDA Label

Note.

Available at: http://www.fasttech.com.

Accessed May 31, 2014.

In summary, older smokers’ perceptions of e-cigarette marketing reflect their formative smoking experiences. Most older smokers began smoking at a time when cigarette ads and smoking behaviors were ubiquitous. Therefore, older smokers are an important segment of the population that should be studied as a distinct sub-group. Further research is needed to identify the impact of marketing messages, particularly aggressive new advertising promoting e-cigarettes as cessation aids and for dual use to cope with smoke-free environments. These findings suggest that to stem the current epidemic of nicotine addiction, the FDA must take immediate action. E-cigarette advertisements use unsubstantiated claims that have the potential to undermine cessation attempts of adults. The FDA’s final rule, Regulations Restricting the Sale and Distribution of Cigarettes and Smokeless Tobacco to Protect Children and Adolescents59 and the Master Settlement Agreement60 already prohibit many of these exploitive techniques for cigarettes and smokeless tobacco. The FDA should use its authority to issue regulations requiring restrictions on the sale and distribution of e-cigarettes for the protection of public health.

Acknowledgment

Research reported in this publication was supported by grant number 1P50CA180890 from the National Cancer Institute and Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Human Subjects Approval

The institutional review board at the University of California, San Francisco approved this study.

Contributor Information

Janine K. Cataldo, University of California, San Francisco School of Nursing, San Francisco, CA.

Anne Berit Petersen, University of California, San Francisco School of Nursing, San Francisco, CA.

Mary Hunter, University of California, San Francisco School of Nursing, San Francisco, CA.

Julie Wang, University of California, San Francisco, Center of Tobacco Control, Research, and Education, San Francisco, CA.

Nicolas Sheon, University of California, San Francisco, Department of Medicine, San Francisco, CA.

References

- 1.Prabhakar V, Jayakrishnan G, Nair S, Ranganathan B. Determination of trace metals, moisture, pH and assessment of potential toxicity of selected smokeless tobacco products. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2013;75(3):262. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.117398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Accessed January 17, 2015]. Report on the Scientific Basis of Tobacco Product Regulation: Third Report of a WHO Study Group. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241209557_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cobb NKBM, Abrams DB, Shields PG. Novel nicotine delivery systems and public health: the rise of the “e-cigarette”. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2340–2342. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.199281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SGR, Glantz SA. Electronic cigarette use among Korean adolescents: a cross-sectional study of market penetration, dual use, relationship to quit attempts and former smoking. J Adolesc Health. 2013;54(6):684–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cobb NK, Abrams DB. E-cigarette or drug-delivery device? Regulating novel nicotine products. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(3):193–195. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1105249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nonnemaker JM, Allen JA, Davis KC, et al. The influence of antismoking television advertisements on cessation by race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and mental health status. PloS one. 2014;9(7):e102943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult cigarette smoking in the United States: Current estimates. [Accessed January 13, 2015];2014 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/

- 8.Food and Drug Administration, National Institutes of Health. Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science (TCORS) [Accessed July 15, 2014];2014 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/PublicHealthScienceResearch/ucm369005.htm.

- 9.Cataldo JK, Malone RE. False promises: the tobacco industry, “low tar” cigarettes, and older smokers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(9):1716–1723. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01850.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yerger VB, Malone RE. African American leadership groups: smoking with the enemy. Tob Control. 2002;11(4):336–345. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.4.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muggli ME, Pollay RW, Lew R, Joseph AM. Targeting of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders by the tobacco industry: results from the Minnesota Tobacco Document Depository. Tob Control. 2002;11(3):201–209. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.3.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Apollonio DE, Malone RE. Marketing to the marginalised: tobacco industry targeting of the homeless and mentally ill. Tob Control. 2005;14(6):409–415. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dillard AJ, McCaul KD, Klein WMP. Unrealistic optimism in smokers: implications for smoking myth endorsement and self-protective motivation. J Health Commun. 2006;11(S1):93–102. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawel A, Anstey KJ. Interventions for midlife smoking cessation: a literature review. Aust Psychol. 2011;46(3):190–195. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(11):930–930. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerr S, Watson H, Tolson D, et al. Smoking after the age of 65 years: a qualitative exploration of older current and former smokers’ views on smoking, stopping smoking, and smoking cessation resources and services. Health Soc Care Community. 2006;14(6):572–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMillen R, Maduka J, Winickoff J. Use of emerging tobacco products in the United States. J Environ Public Health. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/989474. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Etter JF, Bullen C. Electronic cigarette: users profile, utilization, satisfaction and perceived efficacy. Addiction. 2011;106(11):2017–2028. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Regan AK, Promoff G, Dube SR, Arrazola R. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: adult use and awareness of the ‘e-cigarette’ in the USA. Tob Control. 2011;22(1):19–23. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sepe E, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Smooth moves: bar and nightclub tobacco promotions that target young adults. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(3):414–419. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Delaimy WK, Pierce JP, Messer K, et al. The California Tobacco Control Program’s effect on adult smokers: (2) daily cigarette consumption levels. Tob Control. 2007;16(2):91–95. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.017061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson SJ, Glantz SA, Ling PM. Emotions for sale: cigarette advertising and women’s psychosocial needs. Tob Control. 2005;14(2):127–135. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Cancer Society. [Accessed October, 6 2012];2012 Available at: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/002979-pdf.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Lung Association. Big Tobacco’s Next Frontier. [Accessed October 10, 2012];2012 Available at: http://www.lung.org/stop-smoking/tobacco-control-advocacy/reports-resources/tobacco-policy-trend-reports/big-tobaccos-next-frontier.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.King BA, Alam S, Promoff G, et al. Awareness and ever-use of electronic cigarettes among US adults, 2010–2011. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(9):1623–1627. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corey C, Wang B, Johnson SE, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notes from the field: electronic cigarette use among middle and high school students: United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(35):729–730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearson JLRA, Niaura RS, Vallone DM, Abrams DB. E-cigarette awareness, use, and harm perceptions in US adults. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1758–1766. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Regan AK, Promoff G, Dube SR, Arrazola R. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: adult use and awareness of the ‘e-cigarette’ in the USA. Tob Control. 2013;22(1):19–23. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rath J, Villanti AC, Abrams DA, et al. Patterns of tobacco use and dual use in US young adults: the missing link between youth prevention and adult cessation. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:9. doi: 10.1155/2012/679134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.California Tobacco Control Program. State Health Officer’s Report on Tobacco Use and Promotion in California. [Accessed January 17, 2105]; Revised January 2013. Available at: http://www.cdph.ca.gov/Documents/EMBARGOED%20State%20Health%20Officers%20Report%20on%20Tobacco.pdf.

- 31.Pierce JP. Tobacco industry marketing, population-based tobacco control, and smoking behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(6):S327–S334. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halpern-Felsher BL, Biehl M, Kropp RY, Rubinstein ML. Perceived risks and benefits of smoking: differences among adolescents with different smoking experiences and intentions. Prev Med. 2004;39(3):559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seigers DK, Terry CP. Perceptions of risk among college smokers: relationships to smoking status. Addict Res Theory. 2011;19(6):504–509. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sloan F, Platt A. Information, risk perceptions, and smoking choices of youth. J Risk Uncertain. 2011;42(2):161–193. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gray NJ. Nicotine yesterday, today, and tomorrow: a global review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;16(2):128–136. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brody JS. The promise and problems of e-cigarettes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(4):379–380. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201312-2263ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee S, Kimm H, Yun JE, Jee SH. Public health challenges of electronic cigarettes in South Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2011;44(6):235–241. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2011.44.6.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Andrade M, Hastings G, Angus K. Promotion of electronic cigarettes: tobacco marketing reinvented? BMJ. 2013;347 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamin CK, Bitton A, Bates DW. E-cigarettes: a rapidly growing internet phenomenon. An Intern Med. 2010;153(9):607–609. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-9-201011020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grana RA, Ling PM. “Smoking Revolution:” a content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(4):395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Etter JF. Electronic cigarettes: a survey of users. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:231. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pokhrel P, Fagan P, Little MA, et al. Smokers who try e-cigarettes to quit smoking: findings from a multiethnic study in Hawaii. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(9):e57–e62. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vickerman KA, Carpenter KM, Altman T, et al. Use of electronic cigarettes among state tobacco cessation quit-line callers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(10):1787–1791. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kornfield R, Huang J, Vera L, Emery SL. Rapidly increasing promotional expenditures for e-cigarettes. Tob Control. 2014 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051580. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morgenstern M, Sargent JD, Isensee B, Hanewinkel R. From never to daily smoking in 30 months: the predictive value of tobacco and non-tobacco advertising exposure. BMJ open. 2013;3(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emery S, Kim Y, Choi YK, et al. The effects of smoking-related television advertising on smoking and intentions to quit among adults in the United States: 1999–2007. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(4):751–757. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fairchild AL, Bayer R, Colgrove J. The renormalization of smoking? E-cigarettes and the tobacco “endgame”. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(4):293–295. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1313940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Food and Drug Administration. Deeming tobacco products to be subject to the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; Regulations on the Sale and Distribution of Tobacco Products and Required Warning Statements for Tobacco Products. [Accessed January 13, 2015];Fed Regist. 2014 Available at: http://federalregister.gov/a/2014-09491. [PubMed]

- 49.Tan SL, Bigman CA. E-cigarette awareness and perceived harmfulness: prevalence and associations with smoking-cessation outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(2):141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanders-Jackson A, Tan AS, Bigman CA, Henriksen L. Knowledge about e-cigarette constituents and regulation: results from a national survey of US young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu276. pii: ntu276. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delnevo CD, Manderski MTB, Giovino GA. Youth tobacco use and electronic cigarettes. JAMA Pediatrics. 2014;168(8):775–776. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Amrock SM, Zakhar J, Zhou S, Weitzman M. Perception of e-cigarettes’ harm and its correlation with use among US adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(2):32–37. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cho JH, Shin E, Moon S-S. Electronic-cigarette smoking experience among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(5):542–546. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramo DE, Young-Wolff KC, Prochaska JJ. Prevalence and correlates of electronic-cigarette use in young adults: findings from three studies over five years. Addict Behav. 2015;41:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henriksen L. Comprehensive tobacco marketing restrictions: promotion, packaging, price and place. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):147–153. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ribisl KM. Research gaps related to tobacco product marketing and sales in the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(1):43–53. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bahreinifar S, Sheon NM, Ling PM. Is snus the same as dip? Smokers’ perceptions of new smokeless tobacco advertising. Tob Control. 2011;22(2):84–90. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barnett PG, Wong W, Jeffers A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of extended cessation treatment for older smokers. Addiction. 2014;109(2):314–322. doi: 10.1111/add.12404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.FDA Regulations Restricting the Sale and Distribution of Cigarettes and Smokeless Tobacco. [Accessed January 13, 2015];2010 Jun 22; Available at: http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/ProtectingKidsfromTobacco/RegsRestrictingSale/

- 60.Master Settlement Agreement. [Accessed May 31, 2014];2014 May; Available at: http://publichealthlawcenter.org/topics/tobacco-control/tobacco-control-litigation/master-settlement-agreement. [Google Scholar]