Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The aim of this study is to determine whether use of supplemental registered nurses (SRNs) from agencies is associated with patients’ satisfaction.

BACKGROUND

Employment of SRNs is common, but little is known about whether their use is associated with patients’ satisfaction with hospital care.

METHODS

Cross-sectional survey data from nurses in 427 hospitals were linked to American Hospital Association data and patient data from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey.

RESULTS

We found little evidence that patients’ satisfaction with care is related to the use of SRNs. After other hospital and nursing characteristics were controlled, greater use of SRNs was not associated with patients’ global satisfaction, including whether they would rank their hospital highly or recommend their hospital, nor was it associated with nurse communication, medication explanation, or pain control.

CONCLUSIONS

Employment of SRNs does not detract from patients’ overall satisfaction or satisfaction with nurses specifically.

Hospitals employ supplemental registered nurses (SRNs) for various reasons, including vacancies, leave coverage, patient census swings, and expanding services.1–4 Some hospitals recognized for good nursing care, as exemplified by Magnet?® recognition, employ SRNs.1 However, employment of SRNs remains controversial because of concerns about the potential negative impact of temporary nurses on quality of care and questions about cost efficiency.4,5 Understanding the impact of SRN use is critical because although there is not an acute shortage of registered nurses (RNs) in most markets, future shortages are predicted owing to an aging population and increased demand for care associated with expanding coverage under the Affordable Care Act.6

Until recently, there has been little rigorous research on quality of care issues associated with employment of SRNs.3,7,8 There is some documentation of associations between employment of SRNs and adverse patient outcomes9,10; however, most studies have not examined alternative explanations for these associations.

Supplemental registered nurses are similar to permanent RNs on numerous characteristics including education and experience.7,11 On average, SRNs are as qualified as permanent RNs, and many SRNs have permanent hospital positions and work part-time for agencies.7,11 Aiken and colleagues7 found in a study of Pennsylvania hospitals that although there was an association between increased SRN use and poor quality of care, the poor work environments of hospitals employing significant proportions of SRNs explained the association. Replication of this research with a large number of hospitals from 4 states similarly revealed that hospitals with larger proportions of SRNs had significantly higher risk-adjusted mortality after common surgeries, but again, poor work environments explained the association. An in-depth study comparing quality of care and the use of SRNs across 19 units in a large teaching hospital found no evidence of adverse patient outcomes associated with SRN use2 and no adverse implications for hospital costs.12 Research evaluating the impact of the California nurse staffing legislation found that many California hospitals relied on SRNs to meet staffing mandates, and the resulting improved staffing was associated with lower mortality13 and fewer patient falls.14

In this study, we extend previous research on quality of care and SRN use by determining whether patient satisfaction is associated with SRN employment. Patient satisfaction is accepted as a legitimate and important component of hospital quality of care.15 Several large studies have documented the significant contribution of nursing to patients’ overall satisfaction.16–18

This study is the 1st to examine whether patients’ global satisfaction assessments (whether patients would give their hospital a high rating and/or refer family members or friends needing care to that hospital) are associated with the level of SRN use in their hospitals. In addition, we examine whether greater SRN use affects patients’ perceptions of specific aspects of their care.

Methods

Design and Data

This cross-sectional observational study linked 3 data sources—the University of Pennsylvania Multistate Nursing Care and Patient Safety Survey of RNs,19 the American Hospital Association (AHA) annual survey of hospitals,20 and the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) patient survey.21 The nurse survey data were derived from large random samples of RNs in Florida, California, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania who were mailed surveys. The nurse survey was previously approved by the University of Pennsylvania institutional review board (IRB). This study was considered IRB exempt as a secondary analysis of deidentified data. The nurses provided the name of their hospital and information on nurse staffing and the quality of the work environment; details of the nurse survey are described elsewhere.22 The AHA survey provided data on hospital characteristics: bed size, teaching status, technology, ownership. The HCAHPS included patient-reported data about hospital experience and satisfaction. Because AHA and HCAHPS data are reported at the hospital level, we aggregated the nurse data to the hospital level and linked the 3 data sets using a common hospital identifier.

Sample

Hospitals

The 4-state hospital sample used in this study consisted of 427 of the roughly 800 acute care nonfederal hospitals with nurses who responded to the survey in 2006–2008. We included all hospitals with 10 or more nurse respondents that also participated in the HCAHPS survey (voluntary at that time). The average number of nurse respondents per hospital was 49 and ranged between 10 and 282.

Nurses

Nurses in the analytic sample included RNs who worked on a medical, surgical, or intensive care unit. The analytic sample of RNs was 28 407 (27 827 permanently employed RNs, 580 SRNs). Permanently employed RNs reported working as a staff nurse in the participating hospital. The SRNs reported that their employer was a staffing firm independent of the hospital where they worked.

Measures

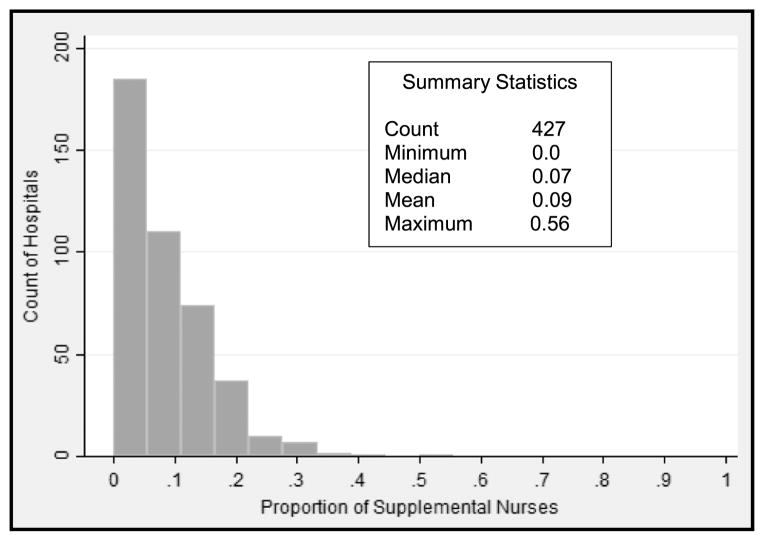

The proportion of SRNs in a hospital (Figure 1) was calculated by dividing the number of SRNs reported by each nurse respondent to be working on their unit during their last shift by the number of total RNs reported to be working on their unit during their last shift. This ratio of SRNs to total RNs was averaged across all nurse respondents in each hospital to create a hospital level measure of the proportion of nurses working in each hospital who were SRNs.

Figure 1.

Number of hospitals by proportion of SRNs.

The other nursing characteristics derived from the nurse survey included measures of staffing (patient-to-nurse ratio) and the nurse work environment, which have been shown previously to be associated with patient satisfaction.16,18 Staffing was estimated from nurses’ reports of how many RNs and patients were on their unit on their last shift. The ratio was calculated as the average number of patients per nurse. A greater workload is represented by a higher patient-to-nurse staffing ratio, measured as a continuous variable.

The nurse work environment was measured using the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI), a National Quality Forum–validated instrument with 31 items grouped into 5 subscales (nurse participation in organization affairs; nursing foundations for quality care; nurse manager ability, leadership, and support; staffing and resource adequacy; and collegial nurse-physician relations).23 We excluded the staffing and resource adequacy subscale because of its correlation with the staffing measure (r = −0.47), following previous research.1,22 The remaining 4 subscales were used to calculate a composite score of the practice environment, which ranged from 1 to 4, with higher scores representing more favorable practice environments. The practice environment was trichotomized into poor (bottom 25%), mixed (26%–74%), and best (top 25%) for analytic purposes. Responses from all nurse respondents, both permanent and supplemental, were used to compute the work environment variable.

Additional hospital characteristics used as controls in our analyses included state, bed size, teaching status, population density, and ownership, based on literature suggesting that these characteristics are associated with HCAHPS scores.16,24 Although there is no previous literature on the effect of hospital technology status on HCAHPS scores, we included it because it had a significant relationship on most HCAHPS ratings in our models.

Population density was defined by a census-derived measure known as core-based statistical area. Population density was categorized into urban and rural, with urban defined as 50 000 or more people and rural defined as 49 999 or fewer people. Hospital bed size was categorized as 100 beds or fewer (small), 101 to 249 beds (medium), or 250 beds or more (large). High-technology hospitals performed open-heart surgery and/or major organ transplantation. Teaching status was indicated by the ratio of medical fellows and residents to hospital beds and was categorized as >1:4 (major teaching hospital), ≤1:4 (minor teaching hospital), or no medical trainees (nonteaching). Ownership was categorized as profit, nonprofit, or government nonfederal.

Patient satisfaction was measured using HCAHPS public-use files. The HCAHPS was voluntary for hospitals at the time the nurse survey data were collected but is now required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Data for the HCAHPS are generated through random sampling of patients after hospital discharge.21 Results for the HCAHPS are reported quarterly by CMS. Results in the public-use files represent aggregated individual patient responses, which are risk adjusted for patient mix and the mode of survey administration.21 The HCAHPS survey contains 21 questions on patient perspectives of care.25 Public-use data are available for 2 single-item global measures, 6 composite measures, and 2 individual items.25 We eliminated 3 topics from consideration as they were unlikely to be related to SRNs: patient communication with doctors (3 items), cleanliness of the environment (1 item), and quietness of the environment (1 item). In this study, we consider the effect of SRNs on the 2 single-item global measures of patient satisfaction and 5 composite measures: communication with nurses (3 items), responsiveness of hospital staff (2 items), pain management (2 items), information about medications (2 items), and discharge information (2 items).

Statistical Analysis

For descriptive purposes, the characteristics of study hospitals were compared based on hospitals with low (<5%), medium (5%–15%), and high (>15%) proportions of SRNs. This categorization is consistent with previous research and was developed on the basis of the distribution of proportion of SRNs across hospitals.1,7 χ2 Tests and F tests (from analysis of variance) were used for group comparisons. The mean HCAHPS outcomes were also compared across hospitals with low, medium, and high proportions of SRNs.

Ordinary least-squares regression models were used to determine the effect of a 10-point increase in the percentage use of SRNs on HCAHPS outcomes, before and after controlling for hospital characteristics, including nursing characteristics. The statistical significance level was set at α < .05 and all tests were 2 tailed.

Results

The characteristics of hospitals with low, medium, and high percentages of SRNs are shown in Table 1. Slightly less than 40% of the hospitals (167/427) had low percentages of SRNs, 45% (192/427) had medium percentages of SRNs, and 15% (68/427) had high percentages of SRNs. The percentage of SRNs across the 427 study hospitals ranged from 0% to 55.5%, with a mean of 8.5% and standard deviation of 7.6%. Hospitals with high percentages of SRNs were significantly more likely than hospitals with low percentages of SRNs to be located in urban locations (97% vs 87%). Hospitals with high percentages of SRNs were also significantly less likely than hospitals with low percentages of SRNs to be nonprofit (54% vs 84%). There were no differences across hospitals with low, medium, and high percentages of SRNs in teaching status, technology, and hospital bed size, nor differences in mean nurse staffing or mean work environment scores.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Hospitals, Overall and Among Hospitals With Different Percentages of SRNs

| Hospital Characteristics | All Hospitals (n = 427)

|

Hospitals With Different Percentages of SRNs

|

P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <5% (n = 167)

|

5%–15% (n = 192)

|

>15% (n = 68)

|

|||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Location | |||||||||

| Urban | 392 | 91.8 | 146 | 87.4 | 180 | 93.8 | 66 | 97.1 | <.05 |

| Rural | 35 | 8.2 | 21 | 12.6 | 12 | 6.3 | 2 | 2.9 | |

| Teaching status | |||||||||

| Nonteaching | 219 | 51.3 | 83 | 49.7 | 99 | 51.6 | 37 | 54.4 | .493 |

| Minor teaching | 174 | 40.8 | 66 | 39.5 | 80 | 41.7 | 28 | 41.2 | |

| Major teaching | 34 | 8.0 | 18 | 10.8 | 13 | 6.8 | 3 | 4.4 | |

| Technology status | |||||||||

| Low technology | 217 | 50.8 | 87 | 52.1 | 98 | 51.0 | 32 | 47.1 | .780 |

| High technology | 210 | 49.2 | 80 | 47.9 | 94 | 49.0 | 36 | 52.9 | |

| Ownership type | |||||||||

| Profit | 81 | 19.0 | 16 | 9.6 | 39 | 20.3 | 26 | 38.2 | <.001 |

| Nonprofit | 314 | 73.5 | 140 | 83.8 | 137 | 71.4 | 37 | 54.4 | |

| Government, nonfederal | 32 | 7.5 | 11 | 6.6 | 16 | 8.3 | 5 | 7.4 | |

| Hospital size | |||||||||

| Small | 36 | 8.4 | 14 | 8.4 | 13 | 6.8 | 9 | 13.2 | .717 |

| Medium | 187 | 43.8 | 72 | 43.1 | 84 | 43.8 | 31 | 45.6 | |

| Large | 204 | 47.8 | 81 | 48.5 | 95 | 49.5 | 28 | 41.2 | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| Nurse staffing | 5.2 | 1.4 | 5.4 | 1.4 | 5.1 | 1.3 | 5.2 | 1.5 | .160 |

| PES-NWI composite score | 2.8 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 0.2 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 2.7 | 0.2 | .120 |

Hospital characteristics are described in the text. Differences between groups were tested using χ2 tests and F tests (analysis of variance).

Percentages may not add to 100% because of rounding.

Table 2 shows the average percentage of patients in the HCAHPS survey who responded favorably to the 2 global measures and the 5 composite measures, 1st across all hospitals and then across hospitals with differing proportions of SRNs. Patients who received care in hospitals with greater than 15% SRNs were significantly less likely to give the hospital a high rating (score of 9 or 10). There was no significant association between the percentage of SRNs and whether the patient would recommend the hospital. Patients in hospitals with the highest proportion of SRNs were significantly less likely to report that nurses always communicated well, gave discharge information, explained medications, provided help as soon as the patient wanted, and controlled pain well. Although these bivariate results suggest that the percentage of SRNs employed by hospitals is significantly related to patient ratings and patients’ perceptions of their care, it is important to recognize that such a conclusion is only tentative. That is, although these results account for differences in patient mix across hospitals by using risk-adjusted HCAHPS measures, they fail to account for other potentially confounding hospital characteristics, such as staffing and work environment, that may be related both to SRN use and patient satisfaction and mediate or distort the relationship between the two.

Table 2.

Percentage of Patients in the Study Hospitals Giving Positive Responses to the HCAHPS Items, Overall and Among Hospitals With Different Percentages of SRNs

| HCAHPS Items | Hospitals with Different Percentages of SRNs

|

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Hospitals | Low (<5%) | Medium (5%–15%) | High (>15%) | ||

| Patients would definitely recommend hospital. | 64.3 (9.8) | 65.5 (9.3) | 63.9 (10) | 62.9 (10.6) | .132 |

| Patients gave hospital a high rating (9 or 10). | 59.3 (8.8) | 61.0 (7.9) | 58.5 (9.2) | 57.3 (9.5) | <.01 |

| Nurses always communicated well. | 68.6 (6.9) | 71.1 (6.0) | 67.6 (6.8) | 65.5 (7.3) | <.0001 |

| Staff gave patients discharge information. | 76.0 (4.6) | 77.3 (4.1) | 75.6 (4.5) | 74.2 (5.0) | <.0001 |

| Staff always explained medications. | 53.6 (6.1) | 55.0 (5.3) | 53.2 (6.0) | 51.0 (7.4) | <.0001 |

| Patients always received help as soon as they wanted. | 55.0 (7.6) | 57.9 (6.8) | 53.8 (7.3) | 51.0 (7.9) | <.0001 |

| Pain was always well controlled. | 64.3 (5.8) | 65.6 (5.0) | 63.8 (5.8) | 62.2 (7.0) | .0001 |

HCAHPS is a hospital-based survey of patients’ hospital experience.

To look beyond the simple associations between SRN employment and patient satisfaction and take account of these potentially confounding factors, we use ordinary least-square regression models. Table 3 shows the effect of a 10-point increase in the use of SRNs on each HCAHPS measure, accounting for differences across hospitals in hospital and nursing characteristics. Model 1 is the unadjusted model, which shows that every 10-point increase in the percentage of SRNs was associated with a decrease in the percentage of satisfied patients, by amounts ranging across the different indicators from 1.2% to 3.2%. Controlling for hospital characteristics in model 2 rendered the associations between SRNs and the 2 global measures of patient satisfaction and the composite measure of pain control insignificant. Controlling for staffing had no impact on associations, but controlling for the work environment attenuated the association between proportion of SRN use and nurse communication and medication information, rendering those associations insignificant. The fully adjusted model (model 4) shows the combined effect of simultaneously controlling for hospital characteristics, including staffing and work environment. There is no significant relationship between SRN use and global measures of patient satisfaction or between SRN use and 3 of the 5 composite measures evaluated. In the fully adjusted model, a significant association remains between higher SRN employment and lower patient satisfaction with hospital staff on discharge instruction and responsiveness that is not explained by hospital characteristics, staffing, and work environment. Each 10-point increase in the proportion of SRNs is associated with a decrease in favorable reports about discharge instruction (−0.57, P < .05) and timely help (−1.32, P < .01).

Table 3.

Effect of a 10-Percentage-Increase in the Use of SRNs on the Percentage of Patients Giving Positive Responses to the HCAHPS Items, Before and After Controlling for Hospital and Nursing Characteristics

| HCAHPS Items | Unadjusted (Model 1) (95% CI) | Hospital Characteristics (Model 2) (95% CI) | Nursing Characteristics

|

Fully Adjusted (Model 4) (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staffing (Model 3a) (95% CI) | Work Environment (Model 3b) (95% CI) | ||||

| Global measures | |||||

| Patients would definitely recommend the hospital. | −1.24a (−2.47 to −0.01) | −0.92 (−2.16 to 0.31) | −0.82 (−2.04 to 0.41) | 0.01 (−1.14 to 1.16) | 0.04 (−1.11 to 1.18) |

| Patients gave a rating of 9 or 10 (high). | −1.73b (−2.83 to −0.63) | −1.02 (−2.12 to 0.09) | −0.92 (−2.02 to 0.17) | −0.16 (−1.20 to 0.87) | −0.14 (−1.17 to 0.88) |

| Composite measures | |||||

| Nurses always communicated well. | −2.59c (−3.42 to −1.76) | −1.03a (−1.84 to −0.22) | −0.98a (−1.79 to −0.18) | −0.62 (−1.42 to 0.18) | −0.61 (−1.40 to 0.19) |

| Staff gave patients discharge information. | −1.53c (−2.08 to −0.97) | −0.90b (−1.47 to −0.34) | −0.82b (−1.38 to −0.27) | −0.60a (−1.15 to −0.05) | −0.57a (−1.12 to 0.03) |

| Staff always explained medications. | −1.86c (−2.60 to −1.11) | −1.00b (−1.77 to −0.24) | −0.96a (−1.72 to −0.20) | −0.65 (−1.40 to 0.11) | −0.64 (−1.39 to 0.12) |

| Patients always received help as soon as they wanted. | −3.22c (−4.13 to −2.31) | −1.68c (−2.59 to −0.77) | −1.61c (−2.52 to −0.71) | −1.34b (−2.25 to −0.43) | −1.32b (−2.22 to −0.41) |

| Pain was always well controlled. | −1.46c (−2.17 to −0.74) | −0.65 (−1.40 to 0.09) | −0.63 (−1.38 to 0.11) | −0.37 (−1.12 to 0.37) | −0.37 (−1.11 to 0.37) |

The fully adjusted model represents the effect of a 10-point increase in the percentage of SRNs on HCAHPS outcomes, controlling for nursing characteristics (staffing and work environment) and hospital characteristics (bed size, urban/rural location, teaching status, technology status, ownership type, and indicator variables for the states in which hospitals are located).

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Effect significant at the P < .05 level.

Effect significant at the P < .01 level.

Effect significant at the P < .001 level.

Discussion

This is the 1st study of the association between use of SRNs and patients’ satisfaction with hospital care. Contrary to concerns about the potential adverse impact of the use of SRNs on quality of care, we find little evidence that SRN use is associated with lower patient satisfaction. Like previous research examining the association between SRN use and poorer quality,1,2,7 we find that global measures of patient satisfaction—patient ratings of hospital care and whether they would recommend the hospital—as well as patients’ perceptions of communication with nurses are unrelated to the employment of SRNs. Indeed, it may be the case that use of SRNs prevented lower hospital ratings than might have occurred if the SRNs were not used. Global indicators of patient satisfaction are considered the most important of the multiple measures included in the HCAHPS survey and have been widely used to evaluate quality of care.16,17,26 In addition, patients’ satisfaction with nurse communication, pain control, and medication information was unrelated to employment of SRNs.

Consistent with previous research,1,7 we found an association between SRN use and lower patient satisfaction in unadjusted models. However, once differences in hospital characteristics and nursing resources were taken into account, these associations were mostly rendered insignificant. This consistent finding across multiple studies underscores the need to look beyond simple associations between SRN use and adverse outcomes that have perpetuated the myth that SRN staffing is associated with poor quality of care. Our findings add to the evidence that associations between substantial use of SRNs and adverse patient outcomes are likely due to characteristics of hospitals that prevent them from recruiting or retaining sufficient numbers of permanently employed nurses. Improving hospital work environments holds promise for improving both nurse retention and patient satisfaction.18

Of the 5 composite patient satisfaction measures evaluated, 2 remained associated with SRN use, even after accounting for hospital characteristics. The 2 items are as follows: (1) After you pressed the call button, did you always receive help as soon as you wanted it, including assistance with toileting? And (2) did doctors, nurses, and other hospital staff talk to you about whether you would have the help you needed when you left the hospital, and did you receive information in writing about symptoms or health problems to look out for after you left the hospital? Others besides nurses are often tasked with answering call lights, and some hospitals rely on non-nurse discharge planners; thus, there may be organizational variables omitted from our models that would have helped explain these associations with SRN use. Regardless, the evidence from our analyses suggests that SRN use is not a major determinant in patient satisfaction.

Limitations of our study include its cross-sectional design, which limits causal inferences. Hospital participation in HCAHPS surveys was voluntary during the study period; therefore, the hospitals we studied may include better hospitals. We were not able to link patients with the specific nurses who cared for them. There may be omitted variables in our models because of data limitations. Finally, like all survey data, the nurse-reported data on SRN use may be inexact.

Conclusion

The employment of SRNs, even in substantial proportions, does not appear to be associated with patients’ overall satisfaction with care or their appraisals of the quality of nurse communication. Our findings contribute to a growing research base suggesting that the use of SRNs is safe and satisfactory to patients and offers hospitals a reasonable strategy for ensuring that adequate nurse staffing is available to hospitalized patients at all times.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the National Institute of Nursing Research (R01NR04513 and T32NR0714) and the American Staffing Association Foundation. The organizations providing research funding did not participate in the research or the decision to publish this manuscript.

Footnotes

The content of this article is the sole responsibility of the authors.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Aiken LH, Shang J, Xue Y, Sloane DM. Hospital use of agency-employed supplemental nurses and patient mortality and failure to rescue. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(3):931–948. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xue Y, Aiken LH, Freund DA, Noyes K. Quality outcomes of hospital supplemental nurse staffing. J Nurs Adm. 2012;42(12):580–585. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e318274b5bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.May JH, Bazzoli GJ, Gerland AM. Hospitals’ responses to nurse staffing shortages. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25(4):w316–w323. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.w316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurst K, Smith A. Temporary nursing staff—cost and quality issues. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(2):287–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartel AP, Beaulieu ND, Phibbs CS, Stone PW. Human capital and productivity in a team environment: evidence from the healthcare sector. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2014;6(2):231–259. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auerbach DI, Staiger DO, Muench U, Buerhaus P. The nursing workforce in an era of health care reform. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1470–1472. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1301694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aiken LH, Xue Y, Clarke SP, Sloane DM. Supplemental nurse staffing in hospitals and quality of care. J Nurs Adm. 2007;37(7/8):335–342. doi: 10.1097/01.nna.0000285119.53066.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pham J, Andrawis M, Shore AD, Fahey M, Morlock L, Pronovost PJ. Are temporary staff associated with more severe emergency department medication errors? J Healthcare Qual. 2011;33(4):9–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2010.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bae SH, Mark B, Fried B. Use of temporary nurses and nurse and patient safety outcome in acute care hospital units. Health Care Manage Rev. 2010;35(3):333–344. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3181dac01c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson FD, Maloney JP, Knight CD, Jennings BM. Utilization of supplemental agency nurses in an army medical center. Mil Med. 1996;161(1):48–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xue Y, Smith J, Freund DA, Aiken LH. Supplemental nurses are just as educated, slightly less experienced, and more diverse compared to permanent nurses. Health Aff. 2012;31(11):2510–2517. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xue Y, Aiken LH, Chappel A, Freund D, Noyes K. Cost outcomes of supplemental nurse staffing in a large medical center. J Nurs Care Qual. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000100. [published online ahead of print December 4, 2014] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Cimiotti JP, et al. Implications of California nurse staffing mandate for other states. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(4):904–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01114.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolton LB, Aydin CE, Donaldson N, et al. Mandated nurse staffing ratios in California: a comparison of staffing and nursing-sensitive outcomes pre- and postregulation. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2007;8(4):238–250. doi: 10.1177/1527154407312737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute of Medicine (IOM) Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Accessed August 26, 2014]. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-A-New-Health-System-for-the-21st-Century.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kutney-Lee A, McHugh MD, Sloane DM, et al. Nursing: a key to patient satisfaction. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(4):w669–w677. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jha AK, Orav J, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients’ perceptions of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921–1931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0804116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aiken LH, Sermeus W, Van den Heede K, et al. Patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of hospital care: cross sectional surveys of nurses and patients in 12 countries in Europe and the United States. BMJ. 2012;344:e1717. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Multi-State Nursing Care and Patient Safety Study Survey Instrument, 2006. Philadelphia, PA: Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.AHA Annual Survey Database. 2006. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21. [Accessed August 26, 2014];HCAHPS Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. http://www.hcahpsonline.org/home.aspx.

- 22.Aiken LH, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, Smith HL, Flynn L, Neff DF. The effects of nurse staffing and nurse education on patient deaths in hospitals with different nurse work environments. Med Care. 2011;49(12):1047–1053. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182330b6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lake ET. Development of the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index. Res Nurs Health. 2002;25(3):176–188. doi: 10.1002/nur.10032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elliot MN, Lehrman WG, Goldstein EH, et al. Hospital survey shows improvements in patient experience. Health Aff. 2010;29(11):2061–2067. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giordano LA, Elliot MN, Goldstein E, Lehrman WG, Spencer PA. Development, implementation, and public reporting of the HCAHPS survey. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;67(1):27–37. doi: 10.1177/1077558709341065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.You LM, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, et al. Hospital nursing, care quality, and patient satisfaction: cross-sectional surveys of nurses and patients in hospitals in China and Europe. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(2):154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]