Abstract

Cytoskeletal contraction is crucial to numerous morphogenetic processes, but its role in early heart development is poorly understood. Studies in chick embryos have shown that inhibiting myosin-II-based contraction prior to Hamburger-Hamilton (HH) stage 10 (33 hr incubation) impedes fusion of the mesodermal heart fields that create the primitive heart tube (HT), as well as the ensuing process of cardiac looping. If contraction is inhibited at or after looping begins at HH10, however, fusion and looping proceed relatively normally. To explore the mechanisms behind this seemingly fundamental change in behavior, we measured spatiotemporal distributions of tissue stiffness, stress, and strain around the anterior intestinal portal (AIP), the opening to the foregut where contraction and cardiac fusion occur. The results indicate that stiffness and tangential tension decreased bilaterally along the AIP with distance from the embryonic midline. The gradients in stiffness and tension, as well as strain rate, increased to peaks at HH9 (30 hr) and decreased afterward. Exposure to the myosin II inhibitor blebbistatin reduced these effects, suggesting that they are mainly generated by active cytoskeletal contraction, and finite-element modeling indicates that the measured mechanical gradients are consistent with a relatively uniform contraction of the endodermal layer in conjunction with constraints imposed by the attached mesoderm. Taken together, our results suggest that, before HH10, endodermal contraction pulls the bilateral heart fields toward the midline where they fuse to create the HT. By HH10, however, the fusion process is far enough along to enable apposing cardiac progenitor cells to keep “zipping” together during looping without the need for continued high contractile forces. These findings should shed new light on a perplexing question in early heart development.

Keywords: biomechanics, morphogenesis, heart fields, anterior intestinal portal, heart tube, chick embryo

1 Introduction

The heart of the vertebrate embryo is initially a relatively simple tube created by the folding and fusion of sheets of cardiac progenitor cells [1–3]. The initially straight heart tube (HT) then undergoes the process of looping, which transforms the HT into a curved tube, laying out the blueprint for the future four-chambered heart [2, 4, 5]. Understanding the mechanisms that create the HT and cause it to loop is of fundamental importance in development, as abnormalities in these vital processes can lead to congenital heart defects and spontaneous abortions during the first trimester [6, 7].

Development of the avian heart parallels that in humans [8], making the chick embryo well suited to studies of early cardiogenesis [2]. The early chick embryo is organized as a flat sheet of cells, consisting of three primary germ layers — endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm. The cardiac progenitor cells reside in the lateral plate mesoderm, where they form a pair of epithelia called heart fields that are situated on the left and right sides of the embryo (figure 1(a)) [1, 9]. After the crescent-shaped head fold forms at about Hamburger-Hamilton (HH) stage 6 (24 hr) [10],1 the heart fields fold out of plane and move toward the embryonic midline, where they meet and begin to fuse at HH9 behind an opening to the foregut called the anterior intestinal portal (AIP) (figure 1(b)). This process gradually forms the primitive HT (future ventricles) and a pair of bilateral omphalomesenteric veins (OVs), which fuse and eventually become the atria (figure 1(c)) [11–13].

Figure 1.

Schematic of early heart development in the chick embryo (ventral view). (Modified from [3] with permission from Annual Reviews.) (a) Heart fields (HFs) are located on left and right sides of the embryo. (b) HFs fold and move toward the midline, where they will fuse behind the anterior intestinal portal (AIP) to create the heart tube (HT). (c) Primitive HT loops rightward and continues to lengthen via fusion of the omphalomesenteric veins (OVs).

Over the last few decades, researchers have identified many of the important genetic factors and biochemical signaling pathways involved in cardiac specification and differentiation [14]. The mechanical forces that physically create and shape the HT, however, have remained poorly understood. Recent studies in our lab have shown that nonmuscle myosin II-based contraction is required to bring the heart fields together to create the HT before the onset of looping at HH10 [13, 15, 16]. In particular, our data suggest that the endoderm actively contracts along the AIP and pulls the mesodermal heart fields toward the midline (figure 2(a),(a′)). Once looping begins, however, fusion and the first phase of looping (c-looping) proceed relatively normally when myosin inhibitors are used to block contraction (figure 2(b),(b′)) [17]. The objective of the present study is to determine why endodermal contraction is needed for normal cardiac morphogenesis before but not after HH10.

Figure 2.

Endodermal contraction and cardiac field fusion around AIP. (a),(b) Bright field images of chick embryo (ventral view) at HH9 (a) and HH10 (b). (a′),(b′) Schematics for cardiac fields (red) at HH9 (a′) and HH10 (b′) (modified from [9] with permission from Elsevier). Before HH9, contraction (white arrows in (a′)) of endoderm (blue arch in (a′)) around the AIP brings the originally separate cardiac fields toward the embryonic midline (dashed line). Once the bilateral cardiac fields meet at the medial AIP (braces in (a) and (a′)), the fields begin fusing to create the heart tube (HT). At HH10, the cylindrical HT is formed and looping begins. The omphalomesenteric veins (OVs) continue to fuse (green arrows in (b′)) to extend the length of the HT as the AIP descends (asterisk indicates the first pair of somites in (a) and (b)). Scale bar: 200 μm.

We explore this question by studying the biomechanics of the tissues around the AIP from HH8+ to HH11. Our measurements reveal spatiotemporal variations in stiffness, stress, and strain along the AIP. Interestingly, AIP stiffness and tension gradients, as well as endodermal shortening rate, peaked at HH9 and decreased afterward. Finite-element models show that these results are consistent with a relatively uniform distribution of endodermal contraction around the AIP that peaks at HH9. From these data, we speculate that endodermal contraction pulls the cardiogenic mesoderm toward the midline prior to HH9, when fusion begins. After this time, however, fusion can continue with reduced levels of contraction, possibly through filopodia-mediated zipping [18].

The present work offers new insight into the spatiotemporal patterning of the heart fields during the HT formation and early-stage looping. It also raises new questions about the cellular mechanisms and signaling networks that regulate these morphogenetic events.

2 Experimental Methods

2.1 Embryo Preparation and Culture

The method for preparation and culture of the embryo is adopted from [19]. Fertile white Leghorn chicken eggs (Sunrise Farms, Catskill, NY) were incubated in a humidified atmosphere at 38 °C for 27–45hr to yield embryos at HH stages 8 to 11 [10]. Embryos were extracted from eggs using filter paper rings (Waterman) and rinsed in PBS. The sandwich structure of embryo and filter paper rings was transferred to a sterile 35mm culture dish (Fisher Scientific, Foster City, CA), and a stainless steel ring was placed on top to hold it in place. The sandwich structure was then covered with a thin layer of liquid culture medium consisting of 89% Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 10% chick serum (Sigma), and 1% antibiotics to eliminate surface tension artifacts [19]. Finally, culture dishes were sealed in plastic bags filled with a humidified mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2, and put into an incubator for continued culture.

To specifically inhibit myosin-II-based cytoskeletal contraction, embryos were cultured in medium containing 50μM (–)-blebbistatin (Bleb, Sigma). A stock solution of 20mM Bleb in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma) was diluted 1:400 in the culture medium to give the final concentration. For controls, the same amount of DMSO was added. To prevent photoinactivation of Bleb during culture and manipulation, culture dishes were covered with aluminum foil whenever possible, and exposure to light was limited. Effectiveness of drug treatments was verified by diminished but not abolished heartbeat and reduced tissue tension.

2.2 Optical Coherence Tomography

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) provides sub-surface structural information of living tissues with high spatial resolution (∼ 10μm) and relatively good penetration depth (up to ∼ 2 mm) [20]. Therefore, OCT is ideal for imaging semitransparent chick embryos at early stages [20]. Stacks of cross-sectional images were obtained with a commercial OCT system (Thorlabs, Newton, NJ), and 3D tissue geometries were reconstructed using the image analysis software Volocity (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) and ImageJ (NIH).

2.3 Stiffness Measurements

To measure tissue stiffness, embryos were transferred individually to a large bath of PBS at room temperature and tested using a custom-built microindentation device [21]. Tissue stiffness was measured at five locations around the AIP — medial, left/right lateral, and left/right mediolateral sites (see figure 5(a)). Briefly, a microindenter was attached to a calibrated cantilever beam and treated with bovine serum albumin to prevent adhesion to the indented tissue. Using customized Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA) codes, motion of the indenter was driven by a piezoelectric actuator, and tissue deformation was recorded and analyzed afterward to calculate local force-deflection curves [21]. The tangential slope of the force-deflection curve at a representative deflection of 10μm was used as a local measure of tissue stiffness. For each location, three consecutive indentations were made to ensure a repeatable response.

Figure 5.

Stiffness measurements around AIP. (a) Tissue stiffness was measured at five locations (arrows) around the AIP (L = lateral, M = medial, ML = mediolateral). (b) Stiffness around the AIP from HH8+ to HH11. At each stage, stiffness decreased from the medial site toward the lateral sites and was relatively symmetric about the embryonic midline, except for HH10+/11-, where the right ML was stiffer than the left ML. Medial stiffness peaked at HH9 and gradually decreased afterward (p < 0.001, two-way ANOVA). (c) Passive stiffnesses in Bleb-treated embryos were significantly lower than corresponding total stiffnesses in control embryos (b). However, the gradient in stiffness remained (p < 0.001, three-way ANOVA). (d) Stiffness gradient (difference in stiffness between the M and L locations). Considering the left-right symmetry in stiffness through HH10, we combined the data for the two L locations. The passive stiffness gradient (Bleb) remained relatively constant over time, while the active stiffness gradient (difference between control and Bleb) peaked at HH9 and decreased afterward, following the trend of the total stiffness gradient (control; p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA). (* p < 0.001, ^ p < 0.005, # p < 0.01; ** denotes p < 0.001 for the annotated data compared with any other data of the same kind at a different stage.) Scale bar: 200 μm.

To investigate how contraction inhibition would affect tissue stiffness, microindentation tests ideally should be carried out in the same embryo before and after exposure to Bleb. Such an approach, however, sometimes was impractical, as repeated indentations often caused damage to the tissue. In those cases, stiffness in either control or Bleb-treated embryos was measured instead. Our results show that the variability introduced by these single measurements was not significant.

2.4 Visualizing Microindentation with OCT

To visualize and qualitatively analyze the tissue deformation near the indenter, we performed microindentation tests on HH8 embryos (n = 3) using our OCT system (see figure 8(a) and supplementary figure S1). Due to limited space, the entire microindentation setup could not be transferred to the OCT platform. Thus, using pulled glass micropipettes, we fashioned microindenters of similar (cylindrical) geometry and attached them to a hand-driven micromanipulator (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA). Real-time OCT images of the deforming tissue were captured during indentation, with the long axis of the indenter aligned with the imaging plane. (Stiffness was not measured in these experiments.) Image stacks were processed later using ImageJ. The leading edge (deforming tissue entering fluid space) and trailing edge (tissue space occupied by fluid) of the deformation were identified via image processing algorithm (supplementary methods and figure S1; see also figure 8(a)).

Figure 8.

Results from finite-element models for microindentation around AIP. (a),(d) Passive (Blebtreated) OCT cross sections through the indentation planes at the medial (a) and lateral (d) AIP, as the indenter (green lines) first comes into contact with the tissue (undeformed) and after indentation (deformed). Red and blue pixels indicate the leading edge and trailing edge of the deformation, respectively (see text and Suppl. Figure S1 for details; NT = neural tube). (b),(e) Undeformed and deformed cross-sectional shapes obtained from models at the medial (b) and lateral (e) AIP. The algorithm used to analyze the OCT images was used to characterize the leading and trailing edges of the model deformation. Both models qualitatively match the tissue deformations observed experimentally. (c),(f) The simulated force-deflection curve at the medial (c) and lateral (f) AIP. Taking the value of the passive shear modulus as μ = 65 Pa yields force-deflection curve that approximately matches experimental data (black lines) for microindentation at the medial AIP (red line in (c)), but not for that at the lateral site (solid blue line in (f)). When the passive modulus is reduced to μ = 15 Pa, however, the simulated force-deflection curve at the lateral AIP (dashed blue line in (f)) matches the experimental data. These results suggest a gradient in passive shear modulus toward the medial AIP. Scale bars: 200 μm.

2.5 Stress Measurements

To estimate tissue tension along the tangential direction, we introduced microsurgical incisions (150-200 μm long) around the AIP using a Gastromaster microdissection device (Xenotek Engineering, Belleville, IL; see figure 6(a),(b)) [13, 22]. Embryos were submerged under PBS at room temperature and properly positioned so that the cutting tip was perpendicular to the curvature of the AIP at each incision. Immediately after cutting, bright field images of the wound were taken using a high magnification camera attached to the microscope. The opening angle of the cut, which is the angle between the two wound edges, was measured using ImageJ and used to characterize the tissue tension normal to the cut direction [13]. To minimize the variability among different embryos, we made multiple cuts either at the medial and lateral AIP or at the mediolateral locations in the same embryo (see figure 6(a),(b)). Cuts at different locations were made in random order and far from each other. Our results show that the change in opening angle caused by introducing a second cut was less than 5 deg.

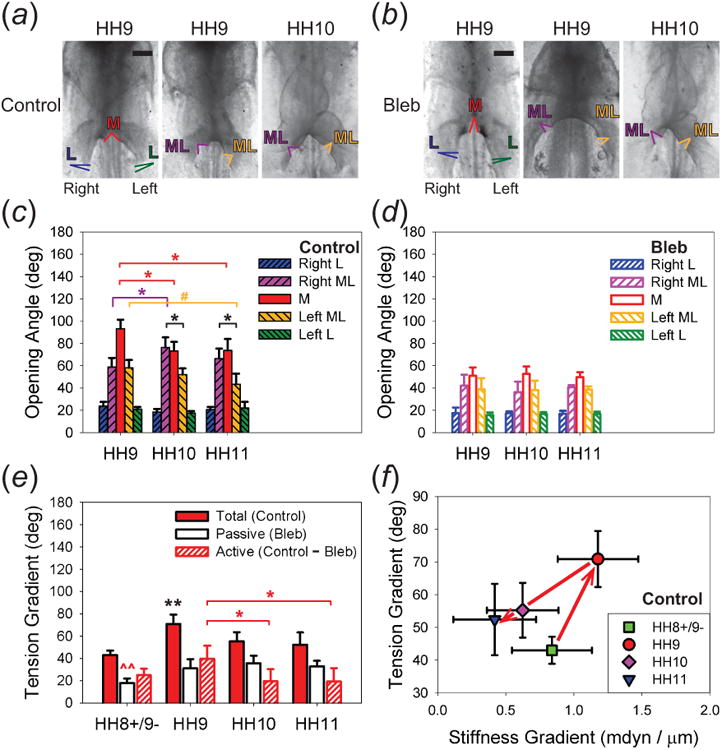

Figure 6.

Tissue stress around AIP. (a),(b) To characterize tissue stress, microsurgical cuts were introduced around the AIP of chick embryos (L = lateral, M = medial, ML = mediolateral). (a),(c) Control embryos. M cuts opened significantly more than L cuts. Opening angles in left and right ML cuts were similar at HH9, but right ML cuts opened significantly more than left ML cuts at HH10 and HH11, suggesting that left-right asymmetry develops in AIP tension after looping begins. (b),(d) Bleb-treated embryos. M and ML opening angles were smaller than controls, indicating a drop in tension. The spatial distribution was relatively symmetric about the midline (p < 0.001, three-way ANOVA). (e) Tension gradient (difference in opening angle between M and L cuts) with HH8+/9- data included from [13]. The total (control) and active (difference between control and Bleb) tension gradients peaked at HH9 and decreased afterward, while the passive (Bleb) gradient remained relatively unchanged from HH9 to HH11 (p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA). (f) Plot of tension gradient vs. stiffness gradient. Note the change in behavior after HH9. Arrows indicate the time course. (* p < 0.001, # p < 0.01; ** and ^^ denote p < 0.001 and p < 0.005, respectively, for the annotated data compared with any other data of the same kind at a different stage.) Scale bars: 200 μm.

2.6 Strain Measurements

To quantify tissue deformation around the AIP, we tracked the movements of fluorescent tissue labels during culture. Prior to culture, DiI (D282, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) labels were injected into the tissue using a pneumatic pump (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) and pulled glass micropipettes mounted to a micromanipulator [22]. To measure tissue movements tangential to the curvature of the AIP, five labels were injected in the endoderm at locations evenly distributed around the AIP (see figure 7(a)).

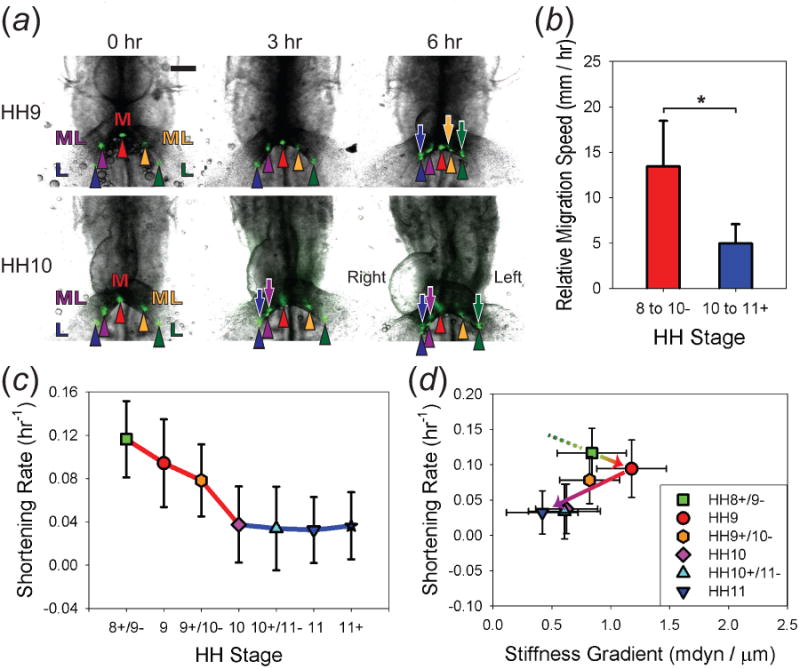

Figure 7.

Tissue motion and deformation around AIP. (a) HH9 (upper panels) and HH10 (lower panels) chick embryos were cultured for 6 hr with fluorescent labels (green dots) injected around the AIP to track tissue movements (L = lateral, M = medial, ML = mediolateral). During culture, L and ML endodermal labels (arrowheads) moved toward the medial AIP, and some split into two, suggesting the mesoderm (arrows) migrates over the underlying endoderm. (b) Mesodermal migration speed relative to endoderm, as measured by tracking the distance between split labels, decreased significantly after HH10 (* p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA). (c) Endodermal shortening rate decreased significantly from HH8+ to HH10 and stayed relatively constant afterward (p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA). All locations are grouped together, as no statistically significant difference was found between different locations within each stage (see Suppl. figure S3). (d) Plot of endodermal shortening rate vs. stiffness gradient. Note the change in behavior after HH9. Arrows indicate the time course. Scale bar: 200 μm.

Bright field and fluorescence images were acquired at the beginning of culture and approximately every 2 hr thereafter using a fluorescence microscope (Leica Camera Inc., Allendale, NJ) and a high magnification camera (Canon USA Inc., Melville, NY). Label tracking was performed later using ImageJ. The distances between adjacent endodermal labels were measured over time, and the tangential stretch ratio (λ) was computed as the current length divided by the reference length. Due to photobleaching and tissue movements, some labels became either invisible or indistinguishable from others after approximately 6 hr. Thus, we chose to inject labels at various stages and quantify endodermal contraction during the following 6 hr. Since computing the cumulative stretch ratio by multiplying incremental stretch ratios [23] could accumulate measurement errors, this method is not suitable for our analysis. Instead, we calculated the shortening rate (Λ̇ = −λ̇) and assumed (to a first approximation)

| (1) |

where L and l are the distances between adjacent labels at time t and t + Δt, respectively.

During culture, some lateral and mediolateral labels split into two with one remaining in the endoderm and the other moving with the adjacent mesoderm. Motions of the split label pair were tracked, and speed of the mesodermal migration relative to the endoderm was computed as the label distance divided by the duration after the splitting occurred.

2.7 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaPlot software (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA). The Holm-Sidak method (one-way, two-way, and three-way ANOVA) was used to compare experimental data among different groups (culture conditions, locations, stages). All experimental measurements are presented as mean ± SD, with statistical significance assumed for p < 0.05.

3 Computational Methods

To help interpret the results from our experiments, we constructed finite-element models for the structures around the AIP. As a first approximation, we assumed a nearly incompressible, pseudoelastic material response for the tissue [24].

3.1 Theory for Modeling Contraction

At the tissue level, active contraction can be simulated as negative growth [25, 26] using the finite growth theory of Rodriguez et al [27]. Here, we briefly summarize the basic idea.

Consider a psudoelastic body that transforms from the reference configuration at time t0 to the current configuration at t. The total deformation is described by the deformation gradient tensor F, which can be decomposed as

| (2) |

where G is the growth tensor and F* is the elastic deformation gradient tensor. The growth tensor defines the stress-free configuration for each material element after it grows. For example, if an unconstrained bar contracts in the x-direction, we can write G = Gxxexex, where Gxx = 1 if the bar is passive and 0 < Gxx < 1 if it is contracting. Mechanical stress is generated through F*, which includes the elastic response to external loads as well as the enforcement of geometric compatibility between material elements after growth.

The Cauchy stress tensor σ, which is assumed to depend only on F*, is given by

| (3) |

where W(E*) is the strain-energy density function, J* = det F* is the elastic volume ratio, and E* = (F*T · F* − I)/2 is the Lagrangian elastic strain tensor with I being the identity tensor and superscript T denoting the transpose.

3.2 Models for Microindentation

As shown below, we observed a gradient in stiffness along the AIP (see figure 5(b)). The apparent stiffness of a membrane depends on material properties, geometry, and tension. Around the AIP, tension in the tissue is generated primarily by contraction, which also affects material properties and is considered in a separate model (see below). To investigate the relative contributions of tissue geometry and material properties to the stiffness gradient, we developed 3D finite-element models to simulate microindentation around the AIP using COMSOL Multiphysics (v3.5, COMSOL Inc., Burlington, MA).

Model Geometry

The model geometry was constructed from OCT cross sections of the AIP taken from an HH8+ embryo (figure 3). At each stage, the most significant difference in tissue stiffness was observed between the medial and lateral regions of the AIP (see figure 5(b),(c)). Thus, we manually segmented OCT cross-sectional images at these locations using ImageJ and imported each into COMSOL (figure 3(b),(c)). By sweeping the 2D cross sections through 3D space, separate models with pseudo-embryonic geometries were created for microindentation at these two locations (figure 3(b′),(c′)).

Figure 3.

Finite-element models for microindentation around AIP. (a) Bright field image of HH8+ embryo with two indentation sites around the AIP: medial and lateral. (b),(c) Medial (b) and lateral (c) OCT cross sections of the AIP with segmented geometries shown in red and blue, respectively. Arrows indicate indentation locations. (b′),(c′) Segmented sections ((b) and (c)) were imported into COMSOL and swept through 3D space to create pseudo-embryonic geometries. These models were used to simulate microindentation at the medial (b′) and lateral (c′) AIP. Due to the left-right symmetry about the embryonic midline (dash-dot line in (a)) at this stage, only half of each geometry is shown. The dorsal side of the neural tube (NT) is placed on rollers to simulate the presence of the relatively stiff vitelline membrane. Scale bar: 200 μm.

Boundary and Contact Conditions

In each model, plane symmetry is assumed about the embryonic midline, and a cylindrical indenter is placed at the indentation site normal to the tissue surface (figure 3(b′),(c′); see also figure 8(b),(e)). For simplicity, we assume that the indenter tip is adherent to the tissue and prescribe a linear function for the axial displacement history at its far end. In addition, a small portion of neural tube is included with its dorsal midline on cranial-caudal oriented rollers to simulate the support by the relatively stiff vitelline membrane. All other boundaries in the model are taken as traction free.

Material Properties

As a first approximation, we neglect any material differences between the endoderm and mesoderm and model the entire tissue as a uniform, pseudoelastic, nearly incompressible material. Contraction is not explicitly included in these models, and so we set G = I. Considering that material nonlinearity is relatively mild at early stages [13, 15, 21], we take the strain-energy density function in the neo-Hookean form

| (4) |

where μ is the small-strain shear modulus, Ī1 = J* −2/3 tr(F*T · F*) = J* −2/3 tr(I + 2E*) is a modified strain invariant, and U(J*) is a penalty function. Here, we choose U(J*) = p(1 – J*) – p2/(2κ), where p is a penalty variable and κ (≫ μ) is the bulk modulus. The indenter is modeled as a Hookean material with the material constants chosen typical for Silica glass (E = 73.1 GPa, v = 0.17) from the COMSOL Material Library.

For each model, the unknown shear modulus μ was determined by solving an inverse problem. We iteratively adjusted the value for μ so that the numerical force-deflection curve given by the model matched our experimental data. During indentation, the indenter force is calculated by integrating the normal axial stress over the cross-sectional area of the indenter. Because the indenter itself deforms only negligibly, the prescribed axial displacement is approximately equal to the simulated tissue deflection.

3.3 OV Model with Endodermal Contraction

To investigate how endodermal contraction and material properties affect tissue strain and stress around the AIP, we created a model for the OVs using the commercial finite-element code ABAQUS (v6.10, SIMULIA, Providence, RI).2 Model geometry was constructed in ABAQUS/CAE, and material properties and cytoskeletal contraction were defined through the ABAQUS user subroutine UMAT [28].

Model Geometry and Boundary Conditions

Since the cross sections of the OVs after HH10 are relatively circular (see figure 4(a′) and also supplementary figure S2(b′)), the OVs are approximated by a toroidal shell (figure 4). Geometric dimensions of the model (figure 4(b),(b′)) are taken from images of a representative HH10 embryo (figure 4(a),(a′)). At this stage of development, the endoderm contacts approximately a quarter of the circumference of the mesoderm, and the tissue layers have approximately equal thickness in the region of contact (figure 4(a′)). For simplicity, however, we do not consider variations in OV thickness in this region (figure 4(b′)).

Figure 4.

Finite-element model for omphalomesenteric veins (OVs) with endodermal contraction. (a) HH10 embryo with a relatively straight heart tube (HT) connected to bilateral OVs. Due to the left-right symmetry about the embryonic midline (dash-dot line), only half of the AIP is considered. (a′) As shown in a mediolateral OCT cross section of the AIP (yellow line in (a)), the endoderm (ENDO, red) contacts approximately a quarter of the mesoderm (MESO, blue). (b),(b′) Curved tube model for the OV with cross-sectional dimensions (b′) taken from (a′). Endodermal contraction (approaching arrows in (b)) is specified in the undeformed toroidal coordinate system {R,Θ,Φ}. Symmetry is enforced at the medial AIP, and the lateral end is free. Scale bars: 200 μm.

Plane symmetry is enforced at the embryonic midline, and only half of the model is shown. Because we found little tension in the lateral regions of the AIP (see figure 6(a)–(d)), we assume that the lateral end of the model is free. In addition, a toroidal coordinate system {R,Θ,Φ} and corresponding unit base vectors {eR,eΘ,eΦ} are defined following the undeformed model geometry (figure 4(b),(b′)), with Θ increasing from the medial (Θ = 0) to the lateral location (Θ = π/2).

Material Properties

For both tissue layers, we take the strain-energy density function W (Eq. 4) from our microindentation model but, for convenience, replace the penalty function with U(J*) = κ [(J*2 − 1)/2 − ln J*]/2. Since separate material properties of the endoderm and mesoderm have not yet been measured, we assume that the value of the shear modulus μ is the same in both layers and take the properties as uniform. (Here, we chose μ = 65 Pa based on the results of our microindentation tests and the corresponding finite-element simulation; see figure 8(c).) A sensitivity analysis shows that large variations in the ratio of the moduli between these two layers change strain and stress distributions quantitatively but not qualitatively, and a gradient in μ affects the results relatively little (see supplementary results 2.3 and figure S4(a)–(d)). Notably, we are more interested here in qualitative trends than in precise quantitative accuracy.

Contraction Simulation

Previous results indicate that the endoderm (not the mesoderm) is the primary contractile tissue layer and that the contraction is relatively isotropic within the tissue plane [13, 22]. Thus, we assume that contraction occurs equally in the Θ and Φ directions in the endoderm with the growth tensor taken in the form

| (5) |

which satisfies the constant volume constraint det G = 1. With G being the contraction variable (0 < G ≤ 1), we consider a gradient in contraction given by

| (6) |

where G0 and G1 are the values of G at the medial (Θ̄ = 0) and lateral (θ = 1) locations of the AIP, respectively. Here, we choose G0 = G1 = 0.7 for the uniform contraction case and G0 = 0.7, G1 = 1 for the gradient contraction case (see figure 9(b)). (A reversed gradient in endodermal contraction (G1 < G0 ≤ 1) causes tension to peak at the mediolateral AIP, contradicting our experimental findings (see figure 6).) The value G0 = 0.7 was estimated from our measurements of endodermal shortening rate from HH10 to HH11+ (Λ̇ ≈ 0.04 hr−1, 6–7 hr, see figure 7(c)). Effects of a contraction gradient are discussed in the Results section, as well as in a sensitivity analysis for this model (see supplementary results 2.3 and figure S4(e),(f)).

Figure 9.

Results from finite-element model for omphalomesenteric vein (OV) with endodermal contraction. (a) Endoderm (ENDO) and mesoderm (MESO) in undeformed OV model. (b) Contraction variable G in endoderm is taken either uniform or linearly varying with Θ. (c) Lagrangian strains and Cauchy stresses are plotted on surface of the deformed model for uniform contraction. Dashed line indicates boundary between endoderm and mesoderm. (d),(e) Distributions of longitudinal strain EΘΘ and stress σθθ along center line of endoderm (curved arrow in (a)). Model results for uniform contraction are qualitatively consistent with our experimental data. Increasing contraction from G = 0.7 (black solid line) to G = 0.5 (blue dash-dot line) matches the strain measurements (from HH10 to HH11+, red circles in (d)) reasonably well, suggesting that endodermal contraction is relatively uniform around the AIP.

4 Experimental Results

4.1 Stiffness around AIP

Using microindentation, we measured tissue stiffness at the medial, mediolateral, and lateral locations around the AIP between HH8+ and HH11 (figure 5(a); n ≥ 6 for each stage). At each stage of development, we observed stiffness gradients around the AIP, with the stiffness decreasing from medial to lateral tissue locations. These gradients were relatively symmetric about the embryonic midline, except for HH10+/11-, where the mediolateral location was stiffer on the right side (figure 5(b); p < 0.001, two-way ANOVA). Over time, the stiffness for the lateral region remained relatively constant, while the medial stiffness peaked at HH9, decreased until HH10, and then stayed relatively unchanged (p < 0.001, two-way ANOVA).

To investigate how cytoskeletal contraction contributes to observed tissue stiffness, we repeated the microindentation tests in embryos exposed to Bleb to obtain a passive measure of tissue stiffness (figure 5(c); n ≥ 5 for each stage). Between HH8+ and HH10, the stiffness in Bleb-treated embryos decreased significantly compared with the corresponding control embryos, and the spatial distribution was relatively symmetric about the midline (p < 0.001, three-way ANOVA). The amount of reduction was approximately 40–60% for the medial and mediolateral locations, although a passive stiffness gradient remained. Overall, the passive stiffness stayed relatively unchanged for each location over time, except that the stiffness for the mediolateral locations increased slightly from HH9+/10- to HH10. As shown by OCT images of AIP cross sections, the average diameter and wall thickness of the OVs did not change significantly after exposure to Bleb (supplementary figure S2). This result suggests that the reduction in stiffness after Bleb exposure can be attributed mainly to tissue relaxation caused by contraction inhibition.

The stiffness gradient is defined here as the difference in tissue stiffness between the medial and lateral locations along the AIP. In addition, we define the active stiffness gradient as the difference between the total (control) and passive (Bleb-treated) stiffness gradients (figure 5(d)). Since the stiffness in control and Bleb-treated embryos was relatively symmetric about the midline through HH10, we combined the data for the two lateral locations. The passive stiffness gradient remained relatively constant over time, while the active stiffness gradient peaked at HH9 and decreased afterward, following the trend of the total stiffness gradient (p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA). These results suggest that changes in the total stiffness gradient are caused primarily by changes in myosin-II-based cytoskeletal contraction.

4.2 Tissue Stress around AIP

To investigate how endodermal contraction affects tension around the AIP, we characterized tissue stress using opening angles generated by microsurgical cutting. In general, the opening angle in control embryos decreased from the medial to the lateral locations at each stage (figure 6(a),(c); n ≥ 5 for each cut at each stage; p < 0.001, two-way ANOVA). The spatial distribution of the opening angle was relatively symmetric about the midline at HH9, while right mediolateral cuts opened significantly more than left mediolateral cuts after this time. This result suggests that left-right asymmetry in tissue tension develops around the AIP after looping begins. Overall, the differences in the opening angle between the medial and mediolateral cuts, as well as between the medial and lateral cuts decreased significantly after HH9.

To examine how contraction affects tissue stress, opening angles were also measured in embryos treated with 50 μM Bleb (n ≥ 5 for each cut at each stage). After 1 hr of exposure, less tension was present around the AIP, as shown by the decrease in opening angle compared to controls (figure 6(b),(d); p < 0.001, three-way ANOVA). In Bleb-treated embryos, the opening angle decreased symmetrically about the embryonic midline and stayed relatively unchanged from HH9 to HH11.

We define the AIP tension gradient as the difference in opening angle between the medial and lateral cuts and also include the data for HH8+/9- from [13]. Our results show that both the total (control) and active (difference between control and Bleb) tension gradients peaked at HH9, decreased significantly from HH9 to HH10, and stayed relatively unchanged afterward (figure 6(e); p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA). The passive (Bleb) gradient, however, increased a little before HH9 and then stayed relatively constant. More importantly, our data also show that the AIP tension gradient correlates with the gradient in total stiffness (which reflects the active stiffness gradient), as they changed synchronously during these stages (figure 6(f)).

Taken together, these results show that the active tension gradient around the AIP increases to a peak at HH9 and decreases afterward, consistent with the trend in the AIP stiffness gradient. These data suggest that changes in tangential tension around the AIP are regulated by myosin-II-based cytoskeletal contraction and likely play an important role in altering tissue stiffness.

4.3 Tissue Movements and Deformation around AIP

In a previous study, we found that endodermal contraction around the AIP pulls the heart fields toward the embryonic midline prior to HH9. While this is the primary mechanism involved in this process, our results also suggested that mesodermal cells may migrate medially over the contracting endoderm. Here, we investigate whether these motions continue after the onset of looping at HH10.

To quantify tissue movements and deformation, fluorescent labels were injected around the AIP of embryos harvested between HH8+ and HH10, and label motions were tracked during 6 hr of culture (figure 7(a); n ≥ 5 for each stage). In all embryos, regardless of their initial stages, lateral and mediolateral labels moved toward the medial label, which remained along the embryonic midline. Meanwhile, some labels split into two, with the mesodermal (more anterior) label moving faster than the endodermal label (figure 7(a)). These observations are qualitatively consistent with our previous study at earlier stages prior to HH9 [13], indicating that the endoderm and mesoderm continue to move toward the midline at different rates after this time.

However, these tissue motions slowed down after HH10 (see arrowheads at 6 hr in figure 7(a)). For comparison, we computed the mesodermal migration speed relative to motion of the endoderm as well as the endodermal shortening rate Λ̇ (figure 7(b),(c)). Since no statistically significant difference was found between various locations within each stage (supplementary figure S3; p > 0.05, two-way ANOVA), we combined the data for all the locations. The results show that the average endodermal shortening rate decreased significantly from HH8+/9- (Λ̇ = 0.116 ± 0.035 hr−1) to HH10 (Λ̇ = 0.038 ± 0.035 hr−1) and stayed relatively constant thereafter (p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA). Similarly, mesodermal migration speed relative to the endoderm also decreased significantly from 13.4 ± 5.0 μm/hr before HH10 to 5.0 ±2.1 μm/hr after HH10 (* p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA).

To determine whether there is a correlation between tissue movement and stiffness, we plotted Λ̇ vs. total stiffness gradient for control embryos (see above; figure 7(d)). Our data indicate that the endodermal shortening rate after HH9 correlated with the AIP stiffness gradient, i.e., they both decreased from HH9 to HH10 and then stayed relatively unchanged. From HH8+ to HH9, however, the AIP stiffness gradient increased a little, while Λ̇ decreased slightly, although the differences between these two stages were not statistically significant.

Taken together, these results show that the endoderm shortens at a rate that decreases before HH10 and remains relatively constant afterward, while migration of mesoderm relative to endoderm slows considerably after HH10. Notably, our date indicate that Λ̇ decreases by almost three-fold from the time the cardiogenic mesoderm begins to fuse at HH9 until looping begins at HH10. This decrease in endodermal shortening rate correlates with decreases in the active stiffness and tension gradients around the AIP (see figures 5(d) and 6(e)), which are caused mainly by a decrease in contractility.

5 Computational Results

To investigate how tissue stiffness, stress, and strain around the AIP are affected by tissue geometry, material properties, and active contraction, we used finite-element models to simulate our microindentation experiments at various locations around the AIP, as well as the behavior of the OVs during endodermal contraction.

5.1 Models for Microindentation around AIP

Our microindentation experiments indicated a stiffness gradient around the AIP, which persisted even after treatment with Bleb (see figure 5(c)). This residual gradient could be attributed to spatial variations in tissue geometry, mechanical properties, or both. To distinguish between these possibilities, we captured OCT cross-sectional images of the tissue at sites corresponding to our microindentation tests (see figure 3(b),(c) and also supplementary figure S2(a′),(b′)). These images show marked differences in both the curvature and thickness of the tissue under the indenter.

To examine whether geometric differences alone could account for the observed gradient, we constructed 3D finite-element models to simulate our microindentation experiments. Since the largest difference in passive stiffness was observed between the medial and lateral regions of the AIP (see figure 5(c)), we created separate models for these two cases. In both models, we used the segmented OCT image corresponding to the indentation site of interest to create the swept model geometry (see figure 3(b′),(c′)).

As a test of our modeling results, we also performed microindentation on the OCT platform and captured real-time images of the tissue deformation under the indenter (see supplementary figure S1). As shown in OCT cross-sectional images of the deforming tissue (figure 8(a),(d)), the leading edge (red pixels) of the deformation represents regions where the deforming tissue had entered into space previously occupied by only fluid, whereas the trailing edge (blue pixels) represents regions where tissue had been replaced by fluid. Our models for microindentation at the medial and lateral locations produced tissue deformation patterns that are qualitatively consistent with those observed using OCT (figure 8(b),(e)). This was not the case for preliminary 2D models, nor simple extruded 3D models, which did not include a crescentic AIP (data not shown).

At the medial location, our simulated force-deflection curve roughly matches our experimental data if the shear modulus μ is taken as 65 Pa (figure 8(c)). Here, we use Bleb-treated experimental data for comparison, since we are interested in the residual (passive) stiffness gradient. When μ = 65 Pa is included in the model for the lateral location, however, the simulated force-deflection curve is much stiffer than that observed experimentally (figure 8(f)). But if μ is reduced to 15 Pa, the simulation result more closely matches the experimental force-deflection curves.

These results suggest that differences in mechanical properties, not geometry, are responsible for the residual stiffness gradient around the AIP after contraction is inhibited by Bleb. We estimate an approximately four-fold decrease in passive tissue modulus between the medial and lateral regions of the AIP at HH8+.

5.2 OV Model with Endodermal Contraction

Previously, we used a simplified 2D model to determine that endoderm is the primary contracting tissue layer during HT formation [13]. Here, to more thoroughly investigate how material properties and endodermal contraction contribute to the stage-dependent strain and stress distributions around the AIP, we use a 3D toroidal model for the OVs. The geometry is based on a mediolateral OCT cross section of the AIP at HH10 (see figure 4(a′)).

As suggested by our stiffness measurements, the shear modulus (μ) and contraction variable (G) of the endoderm are taken either uniform or decreasing with distance from the midline along the AIP (figure 9(a),(b)). In general, contraction causes the endoderm near the inner curvature of the OVs to shorten in the tissue plane, generating tension (σθθ,σϕϕ > 0) and negative strains (EΘΘ, EΦΦ < 0) along both longitudinal and circumferential directions (figure 9(c)). Meanwhile, the adjacent passive mesoderm is compressed longitudinally (EΘΘ, σθθ < 0) and stretched circumferentially (EΦΦ, σϕϕ > 0) by the contracting endoderm. Near the outer curvature, the mesodermal stresses become relatively small, consistent with our prior experimental results [22].

For comparison, the longitudinal strain and stress components (i.e., EΘΘ and σθθ) in the endoderm are plotted along the AIP (figure 9(d),(e)). For uniform modulus and contraction, both EΘΘ and σθθ decrease from the medial AIP (Θ̄ = 0) to the lateral location (Θ̄ = 1). Increasing the amount of contraction (decreased G) increases both the strain magnitude and the stress gradient. More importantly, the strain values given by the model (G = 0.5, blue dash-dot line in figure 9(d)) are in relatively good agreement with those measured from HH10 to HH11+ (see red circles in figure 9(d)), and the stress distribution is consistent with the AIP tension gradient revealed by microsurgical cutting (see figure 6(a),(c)). For a gradient in contraction with uniform μ, EΘΘ increases toward the lateral site and the tension gradient decreases, whereas a gradient in modulus with uniform G changes the strain and stress distributions relatively little (figure 9(d),(e); see also supplementary figure S4(c)–(f)). These results suggest that contraction of the endoderm is relatively uniform, although the passive material properties may vary around the AIP, consistent with our measurements (see figures 5(c), 6(a),(c), and 8(c),(f)). In addition, a sensitivity analysis shows that varying the geometric parameters of this model do not alter the essential trends in our results (supplementary figure S5).

Taken together, these numerical results suggest that the experimental gradients found along the AIP are produced by uniform contraction of the endoderm in conjunction with constraints provided by the passive mesoderm.

6 Discussion

At a fundamental level, morphogenesis is accomplished through the action of mechanical forces, as the simple geometry of the early embryo deforms to give rise to the intricate 3D structures of the adult organism [29]. As one of the most fundamental force-generation mechanisms, cytoskeletal contractility provides major intrinsic driving forces for epithelial morphogenesis [30, 31]. Within animal cells, meshworks of actin microfilaments are cross-linked with myosin motor proteins. These motors then work to pull antiparallel actin fibers toward one another and generate contractile force [31]. In a host of model organisms, contractility has been shown to drive both cell shape changes [32–34] and cell intercalation [35–38], as well as higher order structures like multicellular rosettes [39] and actomyosin purse strings observed during Drosophila dorsal closure [40, 41].

Cytoskeletal contraction not only exerts forces, but also modifies the mechanical properties of the tissue, as actively contracting cells and tissues stiffen [17, 42–44]. In addition, recent experimental work in Drosophila has indicated a possible role for mechanical feedback in regulating myosin II dynamics in the early embryo [36, 45]. These observations reveal a complex and highly integrated functional role for cytoskeletal contractility during development.

Previous work in our lab has suggested that cytoskeletal contraction of the endoderm along the AIP is responsible for pulling the bilaterally situated heart fields toward the embryonic midline before HH9 (30 hr) (figures 1 and 2(a),(a′)) [13]. This contraction is required for heart field fusion and HT formation [13, 15]. After the HT is created at HH10 (33 hr), however, contraction is not necessary for either the progression of fusion or subsequent cardiac c-looping (figure 2(b),(b′)) [15, 17]. The obvious question to ask here is why endodermal contraction is required before but not after HH10. To explore this question, we studied in some detail the mechanical behavior of the tissue around the AIP from HH8+ to HH11 (28–45 hr).

6.1 Tissue Mechanics around the AIP

At each studied stage, our experimental data indicate that tissue stiffness and tangential tension decrease with distance from the embryonic midline along the AIP (figures 5(b) and 6(a),(c)). The tangential strain rate and, therefore, strain relative to HH8+ show that the endoderm shortens relatively uniformly during these stages (supplementary figure S3). Our computational model shows that these stress and strain patterns can be caused by uniform active contraction in the endoderm combined with resistance provided by the passive mesoderm (figure 9). The gradient in tension likely contributes to the measured stiffness gradient, since in-plane tension in a membrane increases its transverse stiffness (figure 6(f)) [46].

To investigate the contribution of cytoskeletal contraction to the observed gradients, AIP stiffness and tangential tension were also measured in embryos with cytoskeletal contraction inhibited. Bleb exposure drops the AIP stiffness and tension considerably, but the passive gradients remain (figures 5(c) and 6(b),(d)). The results of our computer models for microindentation suggest that the residual stiffness gradient is likely produced by a spatial variation in the passive tissue modulus (figure 8(c),(f)). What causes this variation in passive properties is unknown. We speculate that differential amounts of cross-linking within the extracellular matrix, as has been observed between the mesoderm and endoderm [47–50], may generate the passive stiffness gradient. Cross-linking, along with differential growth in the OVs [51], also could produce the passive tension gradient.

Our results are consistent with those of previous studies. The endodermal shortening rate we measured between HH10 and HH11 (figure 7(c)) agrees relatively well with the strain data of [23]. Our microindentation tests revealed a 2–3 fold decrease in tissue stiffness after exposure to Bleb (figure 5(b),(c)), which is consistent with those previously reported in the heart and brain of chick embryos at later stages [15, 52, 53]. We estimated that the passive shear modulus of the AIP varies from 65 Pa at the middle of the AIP to 15 Pa at lateral locations (figure 8(c),(f)); these values are similar to those measured in dorsal isolates of early Xenopus laevis embryos [44] and HH12 chick hearts [24].

More importantly, the measured stiffnesses and stresses changed with time in a relatively consistent manner during the studied stages. The maximum active stiffness and stress (opening angle), which occurred at the midline, increased from HH8+ to HH9, decreased immediately after HH9, and then remained relatively constant after HH10, just as looping began (figures 5(b),(d) and 6(c),(e)). Moreover, after HH10, the distributions of these quantities began to exhibit left-right asymmetry, with both becoming greater near the center of the right OV than the left OV (figures 5(b) and 6(a),(c)). These trends are consistent with the idea that increased tension is the main cause of the increased stiffness (figure 6(f)) [46].

In contrast to these trends, prior to HH9, the average strain rate decreased until HH10, after which it remained relatively constant like the stress and stiffness (figure 7(c),(d)). The reason for this behavior is unknown, but it could be caused by increased resistance to OV deformation exerted by connections to tissue at the ends of the OVs.

6.2 Morphogenetic Implications of Results

Taken together, the results of our study suggest that the endoderm around the AIP undergoes a relatively uniform cytoskeletal contraction that increases in magnitude until HH9 and then decreases afterwards. From this finding and our previous results [13], we speculate that this contraction affects the motion of cardiogenic mesoderm in two main ways.

First, before the onset of looping at HH10, endodermal contraction pulls (convects) the primary heart fields toward the embryonic midline [13], where they fuse to create the HT (figure 10(a),(d),(e)). Second, this contraction establishes a tension gradient, which produces a stiffness gradient in the endoderm, with the greatest tension and stiffness occurring at the midline (figure 10(b),(c)). We speculate that mesodermal cells crawl up this stiffness gradient (durotaxis) to facilitate their motion toward the midline (figure 10(c),(d)) [54, 55]. This mechanism is consistent with our finding that the mesodermal migration speed decreases as the stiffness gradient drops after HH9–10 (figure 7(b),(d)). The tension gradient also may induce an adhesion gradient with similar effects [56, 57].

Figure 10.

Mechanical regulation around AIP. (Modified from [9] with permission from Elsevier.) (a)– (d) Before HH9, (a) contraction (white arrows) of endoderm (blue arch) around the AIP brings the originally separate cardiac fields toward the embryonic midline (dashed line), causing lateral-to-medial gradients in (b) tissue tension and (c) active stiffness. (d) Contraction and stiffness gradient cause mesoderm to move toward the midline (black arrows) via cell convection and migration, respectively. (e) After cardiac fields meet at the embryonic midline, they begin to fuse (green arrows) to create the primitive heart tube (HT) at HH10-. (f) After HH10, when formation of the HT progresses and looping begins, mesodermal fusion can occur with reduced endodermal contraction (OV = omphalomesenteric vein).

As mentioned earlier, previous studies have shown that contraction is necessary for normal heart development before but not during c-looping [13, 17]. Before looping, we speculate that contraction is needed to bring the heart fields together, so they can fuse to create and lengthen the HT (figure 10(a)–(e)) [13]. If contraction is blocked during this time, fusion and looping are disrupted [13]. After looping begins, however, we speculate that the fusion process is far enough along to allow mesodermal cells to fuse without contraction, possibly through filopodia-mediated zipping (figure 10(d)–(f)) [33, 58]. Since contraction is no longer required, we reason that it is down regulated to save energy after HH9. In addition, the decrease in OV strain rate during fusion may indicate increased resistance to OV deformation by surrounding tissues, making convection less effective (figure 7(c)).

Finally, our results suggest that differential contraction around the AIP may be one of several mechanisms that help ensure the normal rightward rotation of the looping heart [22, 59]. The increased stress and stiffness in the right OV after HH10 may indicate that contraction becomes stronger in the right OV than in the left OV during looping (figures 5(b) and 6(a),(c)). This unbalanced force may pull the heart toward the right side of the embryo.

In conclusion, the present study provides a possible answer to the question posed in the title of this paper. By linking cytoskeletal contraction to the motions of the primitive heart fields, this work bridges the gap between the mechanics of HT formation and cardiac looping, adding new insight into these two important morphogenetic events.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Judy Fee and Dmitry Voronov for experimental assistance, as well as Jonathon Young for providing his UMAT code for ABAQUS simulations. We also appreciate insightful discussions with Philip Bayly and Benjamen Filas. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 GM075200, R01 HL083393, and R01 NS070918 (LAT), as well as grant from the American Heart Association 09PRE2060795 (VDV).

Footnotes

Hamburger and Hamilton [10] divided the 21-day incubation period of the chick into 46 stages based on morphological characteristics of the developing embryo.

The reason we used different finite-element software for our models was because these models were developed by different people at different times. We verified that the results given by the two software packages are consistent.

References

- 1.Stalsberg H, DeHaan RL. The precardiac areas and formation of the tubular heart in the chick embryo. Dev Biol. 1969;19:128–159. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(69)90052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taber LA. Biophysical Mechanisms of Cardiac Looping. Int J Dev Biol. 2006;50(2-3):323–332. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.052045lt. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu-Issa R, Kirby ML. Heart Field: From Mesoderm to Heart Tube. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007 Jan;23:45–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Männer J. Cardiac Looping in the Chick Embryo: A Morphological Review With Special Reference to Terminological and Biomechanical Aspects of the Looping Process. Anat Rec. 2000;259:248–262. doi: 10.1002/1097-0185(20000701)259:3<248::AID-AR30>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Männer J. On Rotation, Torsion, Lateralization, and Handedness of the Embryonic Heart Loop: New Insights from a Simulation Model for the Heart Loop of Chick Embryos. Anat Rec Part A. 2004 May;278(1):481–92. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srivastava D, Olson EN. Knowing in Your Heart What's Right. Trends Cell Biol. 1997 Nov;7(11):447–53. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramsdell AF. Left-Right Asymmetry and Congenital Cardiac Defects: Getting to the Heart of the Matter in Vertebrate Left-Right Axis Determination. Dev Biol. 2005;288(1):1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeHaan RL. Development of Form in the Embryonic Heart: An Experimental Approach. Circulation. 1967 May;35(5):821–833. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.35.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abu-Issa R, Kirby ML. Patterning of the Heart Field in the Chick. Dev Biol. 2008;319(2):223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamburger V, Hamilton HL. A Series of Normal Stages in the Development of the Chick Embryo. J Morphog. 1951;88:49–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreno-Rodriguez RA, Krug EL, Reyes L, Villavicencio L, Mjaatvedt CH, Markwald RR. Bidirectional fusion of the heart-forming fields in the developing chick embryo. Dev Dyn. 2006 Jan;235(1):191–202. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cui C, Cheuvront TJ, Lansford RD, Moreno-Rodriguez RA, Schultheiss TM, Rongish BJ. Dynamic positional fate map of the primary heart-forming region. Dev Biol. 2009 Aug;332(2):212–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.05.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varner VD, Taber LA. Not Just Inductive: A Crucial Mechanical Role for the Endoderm during Heart Tube Assembly. Development. 2012 May;139(9):1680–90. doi: 10.1242/dev.073486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brand T. Heart Development: Molecular Insights into Cardiac Specification and Early Morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2003 Jun;258(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rémond MC. Mechanics of the actomyosin cytoskeleton during looping of the embryonic chick heart. D sc., Washington University; St. Louis: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi Y, Yao J, Young JM, Fee JA, Perucchio R, Taber LA. Bending and Twisting the Embryonic Heart: A Computational Model for C-Looping Based on Realistic Geometry. Front Physiol. 5(297):2014. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rémond MC, Fee JA, Elson EL, Taber LA. Myosin-Based Contraction Is Not Necessary for Cardiac C-Looping in the Chick Embryo. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2006 Oct;211(5):443–54. doi: 10.1007/s00429-006-0094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies J. Mechanisms of Morphogenesis. 1st. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voronov DA, Taber LA. Cardiac Looping in Experimental Conditions: Effects of Extraembryonic Forces. Dev Dyn. 2002;224:413–421. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mesud Yelbuz T, Choma MA, Thrane L, Kirby ML, Izatt JA. Optical Coherence Tomography: A New High-Resolution Imaging Technology to Study Cardiac Development in Chick Embryos. Circulation. 2002;106(22):2771–2774. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000042672.51054.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zamir EA, Srinivasan V, Perucchio R, Taber LA. Mechanical Asymmetry in the Embryonic Chick Heart during Looping. Ann Biomed Eng. 2003;31(11):1327–1336. doi: 10.1114/1.1623487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voronov DA, Alford PW, Xu G, Taber LA. The Role of Mechanical Forces in Dextral Rotation during Cardiac Looping in the Chick Embryo. Dev Biol. 2004;272(2):339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramasubramanian A, Latacha KS, Benjamin JM, Voronov DA, Ravi A, Taber LA. Computational Model for Early Cardiac Looping. Ann Biomed Eng. 2006 Jul;34(8):1355–1369. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-9021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zamir EA, Taber LA. Material Properties and Residual Stress in the Stage 12 Chick Heart during Cardiac Looping. J Biomech Eng. 2004;126(6):823–830. doi: 10.1115/1.1824129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taber LA. Biomechanics of Growth, Remodeling, and Morphogenesis. Appl Mechancis Rev. 1995;48(8):487–545. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taber LA. Towards a Unified Theory for Morphomechanics. Philos Trans R Soc A. 2009;367(1902):3555–3583. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2009.0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez EK, Hoger A, Mcculloch AD. Stress-Dependent Finite Growth in Soft Elastic Tissues. J Biomech. 1994;21(4):455–467. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young JM, Yao J, Ramasubramanian A, Taber LA, Perucchio R. Automatic Generation of User Material Subroutines for Biomechanical Growth Analysis. J Biomech Eng. 2010 Oct;132(10):104505. doi: 10.1115/1.4002375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blanchard GB, Adams RJ. Measuring the multi-scale integration of mechanical forces during morphogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011 Oct;21(5):653–63. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wozniak MA, Chen CS. Mechanotransduction in Development: A Growing Role for Contractility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009 Jan;10(1):34–43. doi: 10.1038/nrm2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin AC. Pulsation and Stabilization: Contractile Forces that Underlie Morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2010;341(1):114–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin AC, Kaschube M, Wieschaus EF. Pulsed Contractions of an Actin-Myosin Network Drive Apical Constriction. Nature. 2009;457:495–499. doi: 10.1038/nature07522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solon J, Kaya-Copur A, Colombelli J, Brunner D, Kaya-Çopur A. Pulsed forces timed by a ratchet-like mechanism drive directed tissue movement during dorsal closure. Cell. 2009 Jun;137(7):1331–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blanchard GB, Murugesu S, Adams RJ, Martinez-Arias A, Gorfinkiel N. Cytoskeletal dynamics and supracellular organisation of cell shape fluctuations during dorsal closure. Development. 2010 Aug;137(16):2743–52. doi: 10.1242/dev.045872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skoglund P, Rolo A, Chen X, Gumbiner BM, Keller R. Convergence and extension at gastrulation require a myosin IIB-dependent cortical actin network. Development. 2008 Aug;135(14):2435–44. doi: 10.1242/dev.014704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandez-Gonzalez R, Zallen JA. Cell mechanics and feedback regulation of actomyosin networks. Sci Signal. 2009 Jan;2(101):pe78. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2101pe78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rauzi M, Lenne PF, Lecuit T. Planar polarized actomyosin contractile flows control epithelial junction remodelling. Nature. 2010 Dec;468(7327):1110–4. doi: 10.1038/nature09566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernandez-Gonzalez R, Zallen JA. Oscillatory behaviors and hierarchical assembly of contractile structures in intercalating cells. Phys Biol. 2011 Aug;8(4):045005. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/8/4/045005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blankenship JT, Backovic ST, SP Sanny J, Weitz O, Zallen JA. Multicellular rosette formation links planar cell polarity to tissue morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2006 Oct;11(4):459–70. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kiehart DP. Multiple Forces Contribute to Cell Sheet Morphogenesis for Dorsal Closure in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 2000 Apr;149(2):471–490. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hutson MS, Tokutake Y, Chang MS, Bloor JW, Venakides S, Kiehart DP, Edwards GS. Forces for morphogenesis investigated with laser microsurgery and quantitative modeling. Science. 2003 Apr;300(5616):145–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1079552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wakatsuki T, Kolodney MS, Zahalak GI, Elson EL. Cell mechanics studied by a reconstituted model tissue. Biophys J. 2000 Nov;79(5):2353–68. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76481-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wakatsuki T, Schwab B, Thompson NC, Elson EL. Effects of cytochalasin D and latrunculin B on mechanical properties of cells. J Cell Sci. 2001 Mar;114(Pt 5):1025–36. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.5.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou J, Kim HY, Davidson LA. Actomyosin Stiffens the Vertebrate Embryo during Crucial Stages of Elongation and Neural Tube Closure. Development. 2009;136(4):677–688. doi: 10.1242/dev.026211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pouille PA, Ahmadi P, Brunet AC, Farge E. Mechanical signals trigger Myosin II redistribution and mesoderm invagination in Drosophila embryos. Sci Signal. 2009 Jan;2(66):ra16. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zamir EA, Taber LA. On the Effects of Residual Stress in Microindentation Tests of Soft Tissue Structures. J Biomech Eng. 2004 Apr;126(2):276. doi: 10.1115/1.1695573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Linask KK, Lash JW. Precardiac cell migration: fibronectin localization at mesoderm-endoderm interface during directional movement. Dev Biol. 1986 Mar;114(1):87–101. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drake CJ, Davis LA, Walters L, Little CD. Avian vasculogenesis and the distribution of collagens I, IV, laminin, and fibronectin in the heart primordia. J Exp Zool. 1990 Sep;255(3):309–22. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402550308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wiens DJ. An alternative model for cell sheet migration on fibronectin during heart formation. J Theor Biol. 1996 Mar;179(1):33–9. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1996.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trinh LA, Stainier DYR. Fibronectin Regulates Epithelial Organization during Myocardial Migration in Zebrafish. Dev Cell. 2004 Mar;6(3):371–382. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soufan AT, van den Berg G, Ruijter JM, de Boer PAJ, van den Hoff MJB, Moorman AFM. Regionalized Sequence of Myocardial Cell Growth and Proliferation Characterizes Early Chamber Formation. Circ Res. 2006 Sep;99(5):545–52. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000239407.45137.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramasubramanian A, Nerurkar NL, Achtien KH, Filas BA, Voronov DA, Taber LA. On Modeling Morphogenesis of the Looping Heart Following Mechanical Perturbations. J Biomech Eng. 2008 Dec;130(6):061018. doi: 10.1115/1.2978990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Filas BA, Bayly PV, Taber LA. Mechanical Stress as a Regulator of Cytoskeletal Contractility and Nuclear Shape in Embryonic Epithelia. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011 Jan;39(1):443–54. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0171-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lo CM, Wang HB, Dembo M, Wang YL. Cell movement is guided by the rigidity of the substrate. Biophys J. 2000 Jul;79(1):144–52. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Discher DE, Janmey P, Wang YL. Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science. 2005 Nov;310(5751):1139–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1116995. 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, Firtel RA, Ginsberg MH, Borisy G, Parsons JT, Horwitz AR. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003 Dec;302(5651):1704–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parsons JT, Horwitz AR, Schwartz MA. Cell adhesion: integrating cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular tension. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010 Sep;11(9):633–43. doi: 10.1038/nrm2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Millard TH, Martin P. Dynamic analysis of filopodial interactions during the zippering phase of Drosophila dorsal closure. Development. 2008 Feb;135(4):621–6. doi: 10.1242/dev.014001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taber LA, Voronov A, Ramasubramanian A. The role of mechanical forces in the torsional component of cardiac looping. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010 Mar;1188:103–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.