Abstract

The recent feasibility of genome-wide studies of adaptation in human populations has provided novel insights into biological pathways that have been affected by adaptive pressures. However, only a few African populations have been investigated using these genome-wide approaches. Here, we performed a genome-wide analysis for evidence of recent positive selection in a sample of 120 individuals of Wolaita ethnicity belonging to Omotic-speaking people who have inhabited the mid- and high-land areas of southern Ethiopia for millennia. Using the 11 HapMap populations as the comparison group, we found Wolaita-specific signals of recent positive selection in several human leukocyte antigen (HLA) loci. Notably, the selected loci overlapped with HLA regions that we previously reported to be associated with podoconiosis–a geochemical lymphedema of the lower legs common in the Wolaita area. We found selection signals in PPARA, a gene involved in energy metabolism during prolonged food deficiency. This finding is consistent with the dietary use of enset, a crop with high-carbohydrate and low-fat and -protein contents domesticated in Ethiopia subsequent to food deprivation 10 000 years ago, and with metabolic adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia. We observed novel selection signals in CDKAL1 and NEGR1, well-known diabetes and obesity susceptibility genes. Finally, the SLC24A5 gene locus known to be associated with skin pigmentation was in the top selection signals in the Wolaita, and the alleles of single-nucleotide polymorphisms rs1426654 and rs1834640 (SLC24A5) associated with light skin pigmentation in Eurasian populations were of high frequency (47.9%) in this Omotic-speaking indigenous Ethiopian population.

Introduction

Adaptive response to geographically restricted selective pressures, such as diet, climate, and pathogen burden, is one of the drivers of population differences in frequencies of disease-associated genetic variants.1 Advantageous variants that enhance survival against these selective pressures in human history rise to high frequency, and may now increase risk for chronic diseases as a consequence of lifestyle and ecological changes. This may have contributed to differences in the prevalence of diseases such as type 2 diabetes2, 3 and malaria,4 and traits such as lactase persistence.5 Identifying genomic loci that have been the subject of selection and discerning their relationship with disease phenotypes is instructive in understanding the adaptive genetic basis of population-level differences in the prevalence of common diseases.6, 7, 8

Several genome-wide scans for recent positive selection have identified genomic loci displaying signatures of natural selection.9 However, only a few African populations have been included in these studies.10 The rich genetic, ecological, and socio-cultural diversity of African populations is favorable for the detection of locally restricted and shared selection signals, and for elucidation of putative selective forces.10

The Wolaita are one of the indigenous Ethiopian populations that have inhabited the mid- and high-land areas of southern Ethiopia for several thousand years, and predominantly speak Wolaita, an Omotic branch of the Afroasiatic language family. Compared with the HapMap samples, the Wolaita (WETH) had the smallest genetic differentiation from Kenyan Maasai (MKK) and the largest differentiation from Japanese (JPT), and lay at the farthest end of the African genetic cluster nearest to MKK and farthest from Nigerian Yoruba (YRI).11

In the present study, we performed a genome-wide analysis to identify regions displaying evidence of recent positive selection in a sample of 120 WETH individuals. Our analyses revealed strong evidence of recent positive selection in the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) locus and in genes involved in energy metabolism. We also found that loci selected possibly for survival against pathogens and food deficiency in the past overlapped with genome-wide association study (GWAS) loci linked with protection to podoconiosis,12 and increased risk for metabolic disorders.

Methods

Data sets

We used IlluminaHap 610 Bead Chip genotype data of 120 randomly selected individuals from the Wolaita ethnic group from Southern Ethiopia (WETH; Supplementary Figure 1) who were recruited to serve as controls in a GWAS of podoconiosis.12 Of the 551 840 autosomal single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the raw data set, 39 948 SNPs failed data quality filters (Supplementary Methods). The remaining 511 892 SNPs that passed quality control were merged with the HapMap data set that contained 1 440 616 SNP genotypes in 1184 individuals from 11 populations. A total of 464 642 SNPs were common to both data sets in 1075 unrelated individuals (120 from WETH and 955 unrelated individuals in HapMap 3.2). The ethno-geographical breakdown of the HapMap sample has been described in Supplementary Methods (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-perl/gbrowse/hapmap3r2_B36/).13

Tests for signatures of recent positive selection

We performed the integrated haplotype score (iHS, which identifies partial sweeps)14 and cross-population extended haplotype homozygosity (XP-EHH, which identifies complete sweeps) tests.1, 15 The SNP genotypes were phased using fastPHASE v 1.4.16 The haplotype inference and missing genotype estimation error rates in WETH were similar to or less than those in other African populations16, 17 (detailed in Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). We performed 11 XP-EHH tests comparing WETH with each HapMap sample and one iHS test for WETH (Supplementary Methods). For every SNP, we computed FST using the method of Reynolds, Weir and Cockerham,18 and assessed statistical significance using a Bonferroni-corrected permutation test P-value as described elsewhere.19

Pathway enrichment analysis

We identified all genes within 100 kb up- and down-stream of SNPs in the top 0.1% iHS score and performed pathway enrichment analysis using PANTHER (http://www.pantherdb.org/).20

Results

Signatures of recent positive selection

A total of 453 SNPs were found in the 0.1% tail of the empirical distribution of iHS; SNPs in the HLA locus were overrepresented (82/453, P<0.0001). Moreover, 6 of the 10 SNPs with the highest iHS scores were in the HLA locus (Table 1; Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). The XP-EHH test found 21 SNPs that were selected for in WETH compared with each HapMap sample; the HLA locus was overrepresented with 12 out of the 21 SNPs located near HLA-DQB1 and BTNL2 genes (Table 2). Other selected loci include NCAM1, which is involved in immunity, and ASTN2, which is expressed in the brain and previously reported to be in the top 0.1% selected loci in the Ethiopian Amhara and Ari populations.21

Table 1. Number of SNPs showing evidence of recent positive selection in WETHa.

| |XP-EHH|>2 | Top 0.1% |XP-EHH| | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Total | |iHS|>2 (n=21,157 SNPs,%) | Top 0.1% |iHS|(>3.46); (n=453 SNPs,%) | Total (XP-EHH score at 99.9th percentile) | |iHS|>2 (n=21,157 SNPs,%) | Top 0.1% |iHS| (>3.46); (n=453 SNPs,%) | |

| Each HapMap population as reference | |||||||

| MKK | 22 248 | 2984 (13.4) | 87 (0.4) | 465 (4.01) | 101 (21.7) | 2 (0.4) | |

| LWK | 23 146 | 3532 (15.3) | 130 (0.6) | 460 (3.80) | 217 (47.2) | 37 (8.0) | |

| YRI | 22 872 | 3450 (15.1) | 120 (0.5) | 465 (3.83) | 142 (30.5) | 23 (4.9) | |

| ASW | 23 629 | 3348 (14.2) | 130 (0.6) | 470 (3.89) | 188 (40.0) | 27 (5.7) | |

| CEU | 21 856 | 1863 (8.5) | 54 (0.2) | 459 (3.93) | 42 (9.2) | 3 (0.7) | |

| TSI | 21 703 | 1968 (9.1) | 69 (0.3) | 463 (3.95) | 73 (15.8) | 4 (0.9) | |

| CHB | 21 521 | 1612 (7.5) | 65 (0.3) | 460 (4.45) | 22 (4.8) | 2 (0.4) | |

| CHD | 21 422 | 1552 (7.2) | 60 (0.3) | 455 (4.31) | 16 (3.5) | 1 (0.2) | |

| JPT | 21 536 | 1563 (7.3) | 78 (0.4) | 463 (4.20) | 21 (4.5) | 0 | |

| MEX | 22 210 | 1857 (8.4) | 45 (0.2) | 460 (3.94) | 33 (7.2) | 2 (0.4) | |

| GIH | 21 771 | 1850 (8.5) | 50 (0.2) | 459 (4.28) | 72 (15.7) | 6 (1.3) | |

| Common to HapMap East African populations | |||||||

| MKK and LWK | 7655 | 1600 (20.9) | 60 (0.8) | 45 | 22 (48.9) | 2 (4.4) | |

| Common to all HapMap continental African populations | |||||||

| MKK, LWK,YRI | 4747 | 1211 (25.5) | 53 (1.1) | 13 | 5 (38.5) | 0 | |

| Common to all HapMap African ancestry populations | |||||||

| MKK, LWK, YRI, ASW | 3156 | 910 (28.8) | 52 (1.6) | 7 | 4 (57.1) | 0 | |

| Common to all HapMap populations | |||||||

| 11 HapMap populations | 21 | 5 (23.8) | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Abbreviations: iHS, integrated haplotype score; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; XP-EHH, cross-population extended haplotype homozygosity.

Population groups include Wolaita from Wolaita zone, Ethiopia (WETH), African ancestry in Southwest USA (ASW), Luhya in Webuye, Kenya (LWK), Maasai in Kinyawa, Kenya (MKK), Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI), Tuscans in Italy (TSI), Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry from the CEPH collection (CEU), Mexican ancestry in Los Angeles, California (MEX), Gujarati Indians in Houston, Texas (GIH), Han Chinese in Beijing, China (CHB), Chinese in Metropolitan Denver, Colorado (CHD), Japanese in Tokyo, Japan (JPT).

Table 2. Twenty-one SNPs showing evidence of recent positive selection in WETH compared with each of the 11 HapMap populations (XP-EHH>2)a.

| Peak SNP | Chrb | Posc (hg19) | Allelesd | Predicted function | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs3129963 | 6 | 32380208 | A,G | Upstream | BTNL2 (dist=5308);HLA-DRA (dist=27411) |

| rs6932542 | 6 | 32380262 | G,A | Upstream | BTNL2 (dist=5362);HLA-DRA (dist=27357) |

| rs9268528 | 6 | 32383108 | A,G | Intergenic | BTNL2 (dist=8208);HLA-DRA (dist=24511) |

| rs9268542 | 6 | 32384721 | A,G | Intergenic | BTNL2 (dist=9821);HLA-DRA (dist=22898) |

| rs3135363e | 6 | 32389648 | G,A | Intergenic | BTNL2 (dist=14748);HLA-DRA (dist=17971) |

| rs17212090 | 6 | 32650809 | C,T | Intergenic | HLA-DQB1 (dist=16343); HLA-DQA2 (dist=58354) |

| rs9275141 | 6 | 32651117 | G,T | Intergenic | HLA-DQB1 (dist=16651);HLA-DQA2 (dist=58046) |

| rs2856695 | 6 | 32651894 | G,A | Intergenic | HLA-DQB1 (dist=17428);HLA-DQA2 (dist=57269) |

| rs17212420 | 6 | 32652400 | C,T | Intergenic | HLA-DQB1 (dist=17934);HLA-DQA2 (dist=56763) |

| rs7774434 | 6 | 32657578 | C,T | Intergenic | HLA-DQB1 (dist=23112);HLA-DQA2 (dist=51585) |

| rs7775228 | 6 | 32658079 | T,C | Intergenic | HLA-DQB1 (dist=23613);HLA-DQA2 (dist=51084) |

| rs9275219 | 6 | 32659077 | T,C | Intergenic | HLA-DQB1 (dist=24611);HLA-DQA2 (dist=50086) |

| rs4837514f | 9 | 119181214 | A,G | Intergenic | ASTN2 (dist=6290);PAPPAS (dist=16614); |

| rs7850952 | 9 | 119200847 | C,A | Intron | ASTN2 |

| rs4837530 | 9 | 119205302 | C,T | Intron | ASTN2 |

| rs888401 | 9 | 119207606 | T,C | Intron | ASTN2 |

| rs10961558g | 9 | 14528577 | A,G | Intergenic | NFIB (dist=139595);ZDHHC21 (dist=72492) |

| rs10961560e | 9 | 14529758 | A,G | Intergenic | NFIB (dist=140776);ZDHHC21 (dist=71311) |

| rs2182856e | 9 | 14538257 | C,T | Intergenic | NFIB (dist=139275);ZDHHC21 (dist=72812) |

| rs7850989h | 9 | 14541236 | T,C | Intergenic | NFIB (dist=142254); ZDHHC21 (dist=69833) |

| rs625087h | 11 | 113124432 | T,C | Intron | NCAM1 |

Abbreviations: iHS, integrated haplotype score; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; XP-EHH, cross-population extended haplotype homozygosity.

Population groups include Wolaita from Wolaita zone, Ethiopia (WETH), African ancestry in Southwest USA (ASW), Luhya in Webuye, Kenya (LWK), Maasai in Kinyawa, Kenya (MKK), Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI), Tuscans in Italy (TSI), Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry from the CEPH collection (CEU), Mexican ancestry in Los Angeles, California (MEX), Gujarati Indians in Houston, Texas (GIH), Han Chinese in Beijing, China (CHB), Chinese in Metropolitan Denver, Colorado (CHD), Japanese in Tokyo, Japan (JPT).

Chr=chromosome.

Pos=genomic physical position in base pairs.

Alleles refer to ancestral and derived alleles, respectively. Ancestral state was taken from the ancestral state data released by the 1000G Project at ftp://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/pilot_data/technical/reference/ancestral_alignments, constructed from a four-way primate alignment.

|iHS|>2.

Conserved transcription factor binding sites (score=835, TFBS Accession=M00474 and M00476, TFBS species=mouse and human, TFBS name=FOXO1, FOXO1a, FOXO4).

GERP++ RS score=494, PhastConservation probability score=300.

|iHS|>3.46.

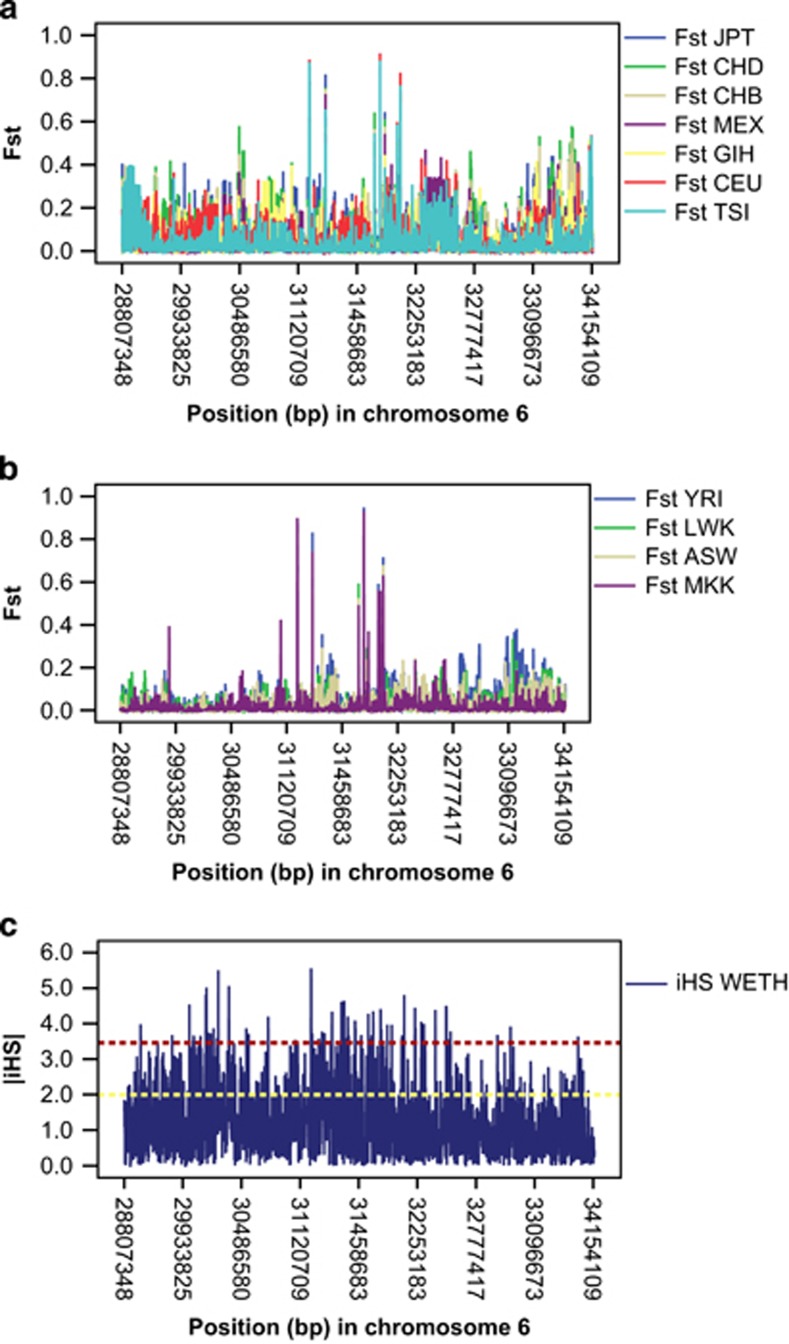

FST test identified 27 SNPs with statistically significant differentiation between WETH and all HapMap samples (Table 3, Supplementary Table 5). The list included the obesity risk locus NEGR1 previously shown to be highly differentiated in sub-Saharan Africans.2 The FST values and iHS scores of the HLA loci had overlapping distributions (Figure 1). The SNP with significantly differentiated FST between WETH and all HapMap populations in the HLA locus (rs2233971, a missense mutation in C6orf15) also had the highest iHS in WETH. Nucleotide substitution (rs2233971=chr6. hg19: g.31080323G>T) in the C6orf15 gene resulting in arginine to serine substitution is predicted to be ‘possibly damaging' by PolyPhen. We also found significant FST differentiations in ASTN2 and HLA-DRA loci, replicating the XP-EHH and iHS findings.

Table 3. SNPs that showed significant F ST-based differentiation between WETH and all HapMap populationsa.

| FST between WETH and | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chrb | SNP | Posc (hg19) | Allelesd | Nearest gene | ASW | CEU | CHB | CHD | GIH | JPT | LWK | MEX | MKK | TSI | YRI |

| 1 | rs11209964 | 72885087 | C,T | NEGR1 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.52 |

| 1 | rs879651 | 116957604 | A,G | ATP1A1OS | 0.17 | 0.4 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.29 |

| 2 | rs11568318 | 234665498 | C,A | LOC100286922 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.32 |

| 2 | rs12328963 | 152091013 | A,G | RBM43 | 0.69 | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.74 |

| 2 | rs1850523 | 180258493 | T,C | na | 0.45 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.53 | 0.56 |

| 3 | rs11705707 | 796528 | G,A | GNA12 | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.67 |

| 4 | rs1869965 | 155969377 | G,T | NPY2R | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.63 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.37 |

| 5 | rs4558959 | 103516803 | C,T | na | 0.54 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.60 | 0.62 |

| 6 | rs1633053 | 29786487 | T,C | HLA-G | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.36 |

| 6 | rs2233971 | 31080323 | G,T | C6orf15 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.89 |

| 6 | rs3129882 | 32409530 | A,G | HLA-DRA | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.36 |

| 7 | rs6955933 | 35913034 | C,T | SEPT7 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.42 |

| 8 | rs323344 | 30702525 | A,C | TEX15 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.35 |

| 8 | rs323345 | 30702602 | C,T | TEX15 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.33 |

| 8 | rs563118 | 41521663 | G,A | ANK1 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.35 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.29 |

| 8 | rs6999665 | 53697552 | A,G | RB1CC1 | 0.45 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.54 |

| 9 | rs35726748 | 137002091 | G,A | WDR5 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.93 |

| 9 | rs803904 | 119431463 | T,C | ASTN2 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.63 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.17 | 0.41 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.30 |

| 9 | rs9697091 | 119397553 | A,G | ASTN2 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.13 | 0.39 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.29 |

| 10 | rs7089341 | 112211051 | C,A | DUSP5 | 0.2 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.29 |

| 11 | rs10769615 | 49802934 | G,A | RP11-707M1.1 | 0.58 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.69 | 0.63 | 0.65 |

| 12 | rs2157873 | 111386667 | G,T | RP1-46F2.2 | 0.51 | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.54 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.59 |

| 13 | rs10219883 | 32708478 | C,T | FRY | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.34 |

| 16 | rs8854 | 88718865 | C,T | MVD | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.94 |

| 18 | rs16956536 | 14130972 | T,C | ZNF519 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| 19 | rs10410147 | 43105373 | G,A | LIPE-AS1 | 0.32 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.44 | 0.16 |

| 20 | rs6099613 | 55988083 | C,T | MIR5095 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.34 |

Abbreviation: SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Population groups include Wolaita from Wolaita zone, Ethiopia (WETH), African ancestry in Southwest USA (ASW), Luhya in Webuye, Kenya (LWK), Maasai in Kinyawa, Kenya (MKK), Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI), Tuscans in Italy (TSI), Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry from the CEPH collection (CEU), Mexican ancestry in Los Angeles, California (MEX), Gujarati Indians in Houston, Texas (GIH), Han Chinese in Beijing, China (CHB), Chinese in Metropolitan Denver, Colorado (CHD), Japanese in Tokyo, Japan (JPT).

Chr=chromosome.

Pos=genomic physical position in base pairs.

Alleles refer to ancestral and derived alleles, respectively. Ancestral state was taken from the ancestral state data released by the 1000G Project at ftp://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/pilot_data/technical/reference/ancestral_alignments, constructed from a four-way primate alignment.

Figure 1.

Distribution of iHS and FST in the HLA locus. (a) FST WETH with non-Africans. (b) FST WETH with HapMap Africans. (c) iHS WETH. Horizontal yellow and red dotted lines represent iHS values of 2 and the top 0.1% threshold. iHS scores quickly decay with distance from the HLA loci with peak iHS scores, consistent with expectations of selective sweeps. Regions of peak iHS in WETH also overlap with those of high FST between WETH and HapMap populations.

Re-construction of founder haplotypes using haploPS22 (details in Supplementary Methods) found 101 signals of selection (Supplementary Table 6), and several overlaps with the iHS, XP-EHH, and FST signals (Supplementary Tables 7–9). To assess whether the allele driving the selection signal was carried by the longest haplotype, as a proof-of-principle, we compared haplotype lengths in the HLA-DRA locus around rs3129882 using HapFinder.23 We observed that the length of the longest haplotype increased significantly when the core haplotype frequency decreased from 25 to 20%, suggesting the rs3129882 [G] variant (frequency=22.9%) or nearby sequence variants may be driving the selection signal (Supplementary Figure 2).

Functional prediction and pathway enrichment analyses

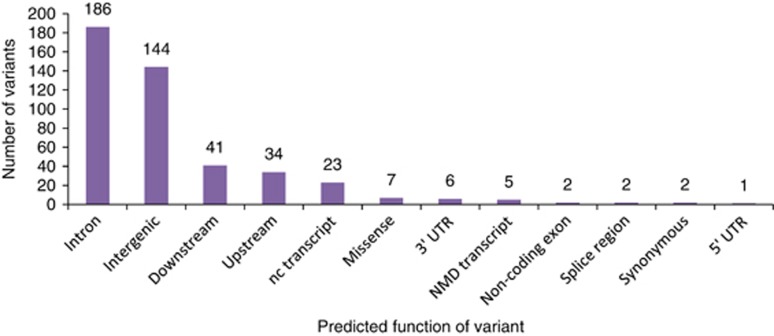

Functional predictions of the SNPs in the top 0.1% tail of the empirical distribution of iHS are presented in Figure 2. Eleven SNPs were exonic, of which eight were missense variants in genes implicated in nervous system development (MAPT/SPPL2C), neuropsychiatric responses (ANKK1), fertilization, muscle development and neurogenesis (AADM28), and genes in the HLA locus (HLA-DOB and ZSCAN12; Table 4).

Figure 2.

Predicted function of variants in the top 0.1% iHS. Predictions are according to Ensembl as defined by the Sequence Ontology Project.

Table 4. Eight non-synonymous variants in the top 0.1% |iHS|a.

| SNP | Chrb | Genomic position (hg19) | |iHS| | Allelesc | Derived allele freq | Gene | Consequence to transcript | Protein residue change | PolyPhen score | SIFT score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs11630901 | 15 | 41819367 | 4.94 | A,G | 0.13 | RPAP1 | Missense/splice region | g. 41819367T>C p.(Arg582Gly) | 0.45d | 0.01e |

| rs12185268 | 17 | 43923683 | 3.55 | G,A | 0.95 | MAPT/SPPL2C | Missense | g. 43923683A>G p.(Ile471Val) | 0 | 1 |

| rs12373139 | 17 | 43924130 | 3.55 | G,A | 0.05 | MAPT/SPPL2C | Missense | g. 43924130G>A p.(Gly620Arg) | 0.001 | 0.63 |

| rs1800497 | 11 | 113270828 | 3.53 | A,G | 0.78 | ANKK1 | Missense | g. 113270828G>Ap.(Glu713Lys) | 0 | 1 |

| rs2232430 | 6 | 28359186 | 3.46 | C,T | 0.10 | ZSCAN12 | Missense | g. 28359186C>T p.(Arg294Lys) | 0.005 | 0.42 |

| rs2233971 | 6 | 31080323 | 5.56 | G,T | 0.11 | C6orf15 | Missense | g. 31080323G>T p.(Arg4Ser) | 0.52d | 0.52 |

| rs2621330 | 6 | 32781524 | 3.69 | C,T | 0.05 | HLA-DOB | Missense | g. 32781524C>T p.(Val244Ile) | 0.02 | 0.95 |

| rs7829965 | 8 | 24207438 | 3.75 | A,G | 0.92 | ADAM28 | Missense | g. 24207438G>A p.(Met684Ile) | 0 | 1 |

Population groups include Wolaita from Wolaita zone, Ethiopia (WETH), African ancestry in Southwest USA (ASW), Luhya in Webuye, Kenya (LWK), Maasai in Kinyawa, Kenya (MKK), Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI), Tuscans in Italy (TSI), Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry from the CEPH collection (CEU), Mexican ancestry in Los Angeles, California (MEX), Gujarati Indians in Houston, Texas (GIH), Han Chinese in Beijing, China (CHB), Chinese in Metropolitan Denver, Colorado (CHD), Japanese in Tokyo, Japan (JPT).

Chr=chromosome.

Alleles refer to ancestral and derived alleles, respectively. Ancestral state was taken from the ancestral state data released by the 1000G Project at ftp://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/pilot_data/technical/reference/ancestral_alignments, constructed from a four-way primate alignment.

Possibly damaging by PolyPhen prediction.

Deleterious by SIFT prediction.

The ‘T-cell activation' PANTHER pathway and the ‘mammary gland development', ‘cellular defense response', ‘response to stimulus', and ‘antigen processing and presentation' PANTHER biological processes showed Bonferroni-corrected statistically significant enrichment (Supplementary Tables 10 and 11).

We found several selection signals in the PPARA gene locus in the XP-EHH test; SNP rs5767743 with the highest iHS score in this locus also had XP-EHH>2 when comparing WETH with CEU, GIH, JPT, MEX, MKK, and TSI. PPARA was a component of the PANTHER-enriched ‘carbohydrate metabolic process' term.

Targets of recent positive selection and common traits

To identify positively selected loci that presumably enhanced survival against pathogens and food shortage in human history, but presently increase risk for chronic diseases, we explored overlaps between the identified selection signals and loci associated with podoconiosis and type 2 diabetes. We also explored selection signals known to have a role in skin pigmentation.

Podoconiosis

We compared podoconiosis GWAS loci12 with this study's selection signals and found that the HLA region containing the 12 XP-EHH SNPs selected for among WETH overlapped with that of the top 10 GWAS SNPs.12 Pair-wise LD calculations showed modest correlation (r2=0.56) between two SNPs with strong XP-EHH (rs9275141 and rs2856695; Table 2) and SNP rs17612858 (chr6.hg19:g.32620622A>T) that has the best GWAS signal for podoconiosis. This correlation was stronger than the average LD in the HLA locus in a 30 kb window (r2=0.20) and between adjacent SNPs (r2=0.33). The frequency of the TA haplotype that carries the positively selected T alleles of rs9275141 and rs2856695 and the podoconiosis-protective rs17612858 A allele was higher than expectation under linkage equilibrium among non-podoconiosis controls (0.61 vs 0.45, P<0.001) and podoconiosis cases (0.42 vs 0.25, P<0.001; Supplementary Tables 12 and 13).

Type 2 diabetes

We searched for overlaps between genes in the top 0.1% iHS and genes (n=79) reported to be associated with type 2 diabetes in two recent meta-analyses.24, 25 We found a novel selection signal at rs9348453, an intronic SNP in CDKAL1.

Skin pigmentation

The SLC24A5 SNPs rs1426654 (chr15.hg19:g.48426484A>G) and rs1834640 (chr15.hg19:g.48392165A>G) implicated in skin pigmentation in Eurasian populations were within the top 1 and 3% iHS in WETH, and the A alleles of both SNPs implicated in light skin pigmentation had high frequency (47.9%) in WETH.

Discussion

We found that the HLA locus and genes involved in immune response and metabolism are enriched for genomic signatures of selection among the Wolaita ethnic group from southern Ethiopia (WETH). The majority of the HLA selection signals found in this study were not detected in previous studies conducted in global populations including a few that involved other African populations.1, 21, 26, 27, 28 Detection of distinct HLA selection signals in WETH is consistent with data that show a high degree of HLA locus differentiation in African populations,29 and the presence of multiple, population-specific targets of selection in the HLA locus.30 These findings imply that diverse African populations should be studied to capture population-specific selection signals and to understand the effects of geographically restricted selective pressures such as diverse demographic history, pathologic, dietary, and climatic challenges.

Clustering of selection signals in the HLA loci exclusively in WETH suggests that the selective forces are locally distinctive and strong. The specific selective force(s) that have operated in this setting are not clearly understood; however, the key role of HLA in immune response against infections suggests that pathogens are plausible candidates.31 Our PANTHER analysis also revealed enhanced selection of other genes that contribute to mammary gland development and immunity, which may be related to nutrition and increased immunity contributing to defense against the high burden of pathogens in the region. It has clearly been shown that both recent positive selection and balancing selection shape the complex nucleotide diversity in the HLA locus.32 In balancing selection, the equilibrium frequency favoring different alleles can fluctuate with time and space. When environments change over time, recent positive selection can lead one allele to increase in frequency with the collective selection events ultimately maintaining multiple alleles at a locus.33 Moreover, the haplotype pattern around a locus under recent balancing selection can resemble an incomplete sweep of positive selection.8, 34, 35 Therefore, the LD-based tests we used detect recent balancing as well as positive selection, and currently available analysis methods have little power to distinguish these.35 The possible effect of long-term balancing selection on HLA diversity in Ethiopia has been shown by analysis of 61 global populations by Prugnolle et al. and analysis of 535 populations by Sanchez-Mazas et al.36, 37 These studies found that HLA genetic diversity is positively correlated with pathogen diversity of a geographic region and inversely correlated with geographic distance from Ethiopia.36, 37 This corroborates previous evidence suggesting the presence of more pathogens in Africa where humans have lived the longest, and in Ethiopia, where pathogen richness (the number of kinds of pathogens) is one of the greatest on a global scale.38 Historical accounts and archeological evidence indicate expansion of agriculture in the fertile Ethiopian highlands, and formation of urban centers at least as early as the fifth millennium BC.39 These markers of ancient civilization were linked with more settled life, high population density and poor hygienic conditions that facilitated spread of pathogens, which are still a significant cause of mortality and morbidity in the region. Taken together, these data suggest that pathogens are the strongest driving force behind the distinctive and highly enriched selection signals in the HLA locus that we found among this Ethiopian population.

We found signatures of positive selection in genes involved in metabolic processes including a novel selection signal in CDKAL1, a gene that has been implicated in type 2 diabetes, pancreatic β-cell function, and insulin secretion.24, 25, 40, 41, 42, 43 CDKAL1 inhibits the CDK5 protein leading to enhanced insulin secretion under conditions of high glucose levels.44, 45 Therefore, reduced expression of CDKAL1 inhibits insulin secretion leading to an impaired response to glucotoxicity and increased risk for type 2 diabetes.46 The CDKAL1 rs9348453 ancestral A allele in the haplotype favored by selection had high frequency (>70%) in all population groups analyzed in this study. Characterization of sequence variation produced by the 1000G Project shows that rs9348453 has potential regulatory role in human skeletal muscle myoblast cell lines that are used to study diabetes and insulin resistance. Moreover, rs9348453 is correlated (r2=0.73) with rs79915874 (chr6.hg19:g.21005146T>C) that has been predicted to disrupt binding motifs of the hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 transcription factor, which is mainly expressed in the liver and pancreatic β cells. Taken together, these findings suggest that CDKAL1 may be one of the key energy metabolism genes targeted by recent selection.5, 47, 48 Investigation of this novel locus of selection using targeted-sequencing may provide new insights in the pathogenesis of diabetes and metabolic disorders.

The carbohydrate metabolic process term that was significantly enriched in PANTHER included the PPARA (peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha) gene. PPARA plays a key role in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism by direct regulation of numerous genes encoding enzymes and transport proteins that are important for glucose homeostasis and lipid metabolism.49 PPARA is activated during energy deprivation and plays a key role in the management of energy stores during fasting and prolonged food deprivation.50, 51, 52, 53 Within the context of the historic dietary experiences of the Wolaita people, selection pressure acting on the PPARA may be due to the long-term consumption of Ensete ventricosum. Enset is a food crop that resembles the banana plant and has high-carbohydrate and low-fat content. It is the main food source in the Wolaita area, with more than 10 million people in the highlands of southern Ethiopia depending on it for food, fiber, animal forage, construction materials, and medicines.54 The Omotic-speaking people of Ethiopia introduced enset as a food source and domesticated the plant as early as 10 000 years ago in response to a food crisis.55 A well-known feature of the enset plant is its drought tolerance, hence, it was called the ‘tree against hunger' by European travelers to Ethiopia in the 1600s.54 Given this history, we propose that the diet-induced positively selected haplotype we found may inhibit PPARA expression leading to a metabolic adaptation in which lipid oxidation is reduced and carbohydrate oxidation is enhanced even in times of energy deprivation. Consistent with our observation, others have reported signals of natural selection in PPARA in populations of diverse ancestry from widely ranging ecological regions.1 In all, our findings of selection signals in PPARA and NEGR1 (an obesity locus that has been shown to be highly differentiated among sub-Saharan Africans2) strengthen emerging investigations that show the impact of natural selection on genetic variants that shape metabolic processes in coping with fluctuating food availability and dietary adaptation, and dramatic shifts in food consumption in human history.2, 5, 47, 48

Along with diet, high-altitude hypoxia may have exerted an additional selective pressure on the PPARA gene in the Wolaita people who have inhabited the Ethiopian highlands for millennia. Similar to the effect of a high-carbohydrate and low-fat content diet, genetic and non-genetic adaptations to hypoxia at high altitudes lead to a shift from lipid to carbohydrate oxidation, promotion of lipid storage, and preference for anaerobic glycolysis for energy expenditure.56 Consistent with this thinking, previous studies have shown that PPARA may be implicated in high-altitude adaptation in the Amhara population group from northern Ethiopia and in Tibetans.21, 57 Also, correlation between the selected PPARA haplotype and serum-free fatty acid levels has been observed among Tibetans.56 In all, PPARA may have been targeted by reinforced selective forces from the nutritional content of the enset diet and high-altitude hypoxia; these observations may explain our findings of several PPARA selection signals in both the iHS and XP-EHH tests. Our finding of PPARA gene selection has relevance for cardio-metabolic diseases because genetic variants in PPARA have been found to be associated with blood lipid levels, lipoproteins, and type 2 diabetes.58 Reduction in fatty acid oxidation through PPARA inhibition results in increased levels of stored and circulating lipids, a known risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and the metabolic syndrome.59 This advantageous genetic adaptation of the past may fuel the rise in cardiovascular diseases in Ethiopians,60, 61 and perhaps other populations undergoing urbanization and transition toward lipid-rich diets and sedentary lifestyles. The cardio-metabolic effect of this genetic adaptation, which may have important clinical and public health implications, needs to be investigated further in other African and global populations.

We found selection signals in WETH (an Omotic language speaking ethnic group) around the SLC24A5 gene implicated in skin pigmentation in European and West Asian populations.1, 15 A recent study found these loci in the top 5% of selection signals for Semitic-Cushitic-speaking Ethiopian populations, but not in a combined analysis of three Omotic language speaking Ethiopian ethnic groups (Wolaita, Ari Agricultural, and Ari Blacksmith).62 Moreover, we found a higher frequency of the alleles associated with light skin pigmentation in Eurasian populations in WETH (A allele frequency of both SNPs=47.9% in WETH vs 23% in the combined Omotic sample reported62). Our study had a larger sample of the Wolaita than the previous study (n=120 vs n=8). Moreover, the genetic, geo-climatic, and demographic differences between the Wolaita and the Ari may have masked the selection signal during combined analysis of the ethnic samples in the previous study.62 The SLC24A5 gene's derived Ala111Thr allele (rs1426654 A allele) is present at low frequencies in other sub-Saharan African populations.63 Our finding of high frequency of this allele in an Omotic-speaking indigenous southern Ethiopian ethnic population that has little shared genetic ancestry with Eurasians62 strengthens previous suggestions of the need for studies to understand whether the derived alleles underlying the adaptive response originated in East Africa or Eurasia.63

We replicated several genes reported to be under selection by at least two genome-wide scans (Supplementary Table 14). Consistent with a study which demonstrated that inflammatory-disease susceptibility loci are enriched for signatures of recent positive selection,64 we identified selection signals in loci implicated in podoconiosis. The findings suggest that positive selection has favored the haplotypes carrying the podoconiosis-protective alleles. The presence of more risk alleles in podoconiosis cases may be due to the effect of mate selection because individuals from podoconiosis affected families are subject to social stigmatization and are excluded from marriage by non-affected community members who recognize that podoconiosis is heritable.65, 66, 67

Overall, this study provides strong evidence of selection in the HLA locus and metabolism genes in an Ethiopian population. It is likely that the burden of a diverse array of pathogens and adaptations to dietary fluctuations may represent the strongest selective forces in the history of this African population. Furthermore, our findings of overlaps between several previously reported disease susceptibility GWAS loci and targets of recent positive selection demonstrate the usefulness of African population samples to elucidate the adaptive genetic basis for many complex diseases.

Acknowledgments

The research project was supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant #079791), and the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, in the Center for Research on Genomics and Global Health (CRGGH). The CRGGH is also supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. We thank staff of the Mossy Foot Treatment and Prevention Association (now Mossy Foot International) for coordinating the fieldwork.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- Pickrell JK, Coop G, Novembre J et al: Signals of recent positive selection in a worldwide sample of human populations. Genome Res 2009; 19: 826–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimentidis YC, Abrams M, Wang J, Fernandez JR, Allison DB: Natural selection at genomic regions associated with obesity and type-2 diabetes: East Asians and sub-Saharan Africans exhibit high levels of differentiation at type-2 diabetes regions. Hum Genet 2011; 129: 407–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinan KJ: Worldwide distribution of type II diabetes-associated TCF7L2 SNPs: evidence for stratification in Europe. Biochem Genet 2012; 50: 159–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamblin MT, Di Rienzo A: Detection of the signature of natural selection in humans: evidence from the Duffy blood group locus. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 66: 1669–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tishkoff SA, Reed FA, Ranciaro A et al: Convergent adaptation of human lactase persistence in Africa and Europe. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayodo G, Price AL, Keinan A et al: Combining evidence of natural selection with association analysis increases power to detect malaria-resistance variants. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 81: 234–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman SR, Andersen KG, Shlyakhter I et al: Identifying recent adaptations in large-scale genomic data. Cell 2013; 152: 703–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson EK, Kwiatkowski DP, Sabeti PC: Natural selection and infectious disease in human populations. Nat Rev Genet 2014; 15: 379–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akey JM: Constructing genomic maps of positive selection in humans: where do we go from here? Genome Res 2009; 19: 711–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MC, Tishkoff SA: African genetic diversity: implications for human demographic history, modern human origins, and complex disease mapping. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2008; 9: 403–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekola-Ayele F, Adeyemo A, Aseffa A et al: Clinical and pharmacogenomic implications of genetic variation in a Southern Ethiopian population. Pharmacogenomics J 2014, e-pub ahead of print 29 July 2014. doi:10.1038/tpj.2014.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tekola Ayele F, Adeyemo A, Finan C et al: HLA class II locus and susceptibility to podoconiosis. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1200–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L et al: Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature 2010; 467: 52–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voight BF, Kudaravalli S, Wen X, Pritchard JK: A map of recent positive selection in the human genome. PLoS Biol 2006; 4: e72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti PC, Varilly P, Fry B et al: Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations. Nature 2007; 449: 913–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheet P, Stephens M: A fast and flexible statistical model for large-scale population genotype data: applications to inferring missing genotypes and haplotypic phase. Am J Hum Genet 2006; 78: 629–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres AM, Clark AG, Shimmin L, Boerwinkle E, Sing CF, Hixson JE: Understanding the accuracy of statistical haplotype inference with sequence data of known phase. Genet Epidemiol 2007; 31: 659–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds J, Weir BS, Cockerham CC: Estimation of the coancestry coefficient: basis for a short-term genetic distance. Genetics 1983; 105: 767–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagh K, Bhatia A, Alexe G et al: Lactase persistence and lipid pathway selection in the Maasai. PLoS One 2012; 7: e44751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi H, Muruganujan A, Thomas PD: PANTHER in 2013: modeling the evolution of gene function, and other gene attributes, in the context of phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 41: D377–D386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinfeldt LB, Soi S, Thompson S et al: Genetic adaptation to high altitude in the Ethiopian highlands. Genome Biol 2012; 13: R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Ong RT, Pillai EN et al: Detecting and characterizing genomic signatures of positive selection in global populations. Am J Hum Genet 2013; 92: 866–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong RT, Liu X, Poh WT, Sim X, Chia KS, Teo YY: A method for identifying haplotypes carrying the causative allele in positive natural selection and genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 2011; 27: 822–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AP, Voight BF, Teslovich TM et al: Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 2012; 44: 981–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena R, Elbers CC, Guo Y et al: Large-scale gene-centric meta-analysis across 39 studies identifies type 2 diabetes loci. Am J Hum Genet 2012; 90: 410–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro LB, Laval G, Quach H, Patin E, Quintana-Murci L: Natural selection has driven population differentiation in modern humans. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis JP, Scheinfeldt LB, Soi S et al: Patterns of ancestry, signatures of natural selection, and genetic association with stature in Western African pygmies. PLoS Genet 2012; 8: e1002641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson SH, Hubisz MJ, Clark AG, Payseur BA, Bustamante CD, Nielsen R: Localizing recent adaptive evolution in the human genome. PLoS Genet 2007; 3: e90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao K, Moormann AM, Lyke KE et al: Differentiation between African populations is evidenced by the diversity of alleles and haplotypes of HLA class I loci. Tissue Antigens 2004; 63: 293–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia G, Patterson N, Pasaniuc B et al: Genome-wide comparison of African-ancestry populations from CARe and other cohorts reveals signals of natural selection. Am J Hum Genet 2011; 89: 368–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro LB, Quintana-Murci L: From evolutionary genetics to human immunology: how selection shapes host defence genes. Nat Rev Genet 2010; 11: 17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubb KL, Bovee D, Buckley D et al: Scan of human genome reveals no new Loci under ancient balancing selection. Genetics 2006; 173: 2165–2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGiorgio M, Lohmueller KE, Nielsen R: A model-based approach for identifying signatures of ancient balancing selection in genetic data. PLoS Genet 2014; 10: e1004561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg OD, Mack SJ, Lancaster AK et al: Balancing selection and heterogeneity across the classical human leukocyte antigen loci: a meta-analytic review of 497 population studies. Hum Immunol 2008; 69: 443–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres AM, Hubisz MJ, Indap A et al: Targets of balancing selection in the human genome. Mol Biol Evol 2009; 26: 2755–2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prugnolle F, Manica A, Charpentier M, Guegan JF, Guernier V, Balloux F: Pathogen-driven selection and worldwide HLA class I diversity. Curr Biol 2005; 15: 1022–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Mazas A, Lemaitre JF, Currat M: Distinct evolutionary strategies of human leucocyte antigen loci in pathogen-rich environments. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2012; 367: 830–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn RR, Davies TJ, Harris NC, Gavin MC: Global drivers of human pathogen richness and prevalence. Proc Biol Sci 2010; 277: 2587–2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henze PB: Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Okada Y, Kubo M, Ohmiya H et al: Common variants at CDKAL1 and KLF9 are associated with body mass index in east Asian populations. Nat Genet 2012; 44: 302–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak SH, Choi SH, Jung HS et al: Clinical and genetic risk factors for type 2 diabetes at early or late post partum after gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98: E744–E752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng MC, Saxena R, Li J et al: Transferability and fine mapping of type 2 diabetes loci in African Americans: the Candidate Gene Association Resource Plus Study. Diabetes 2013; 62: 965–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe L, Tura A, Patel SK et al: Common variants of the novel type 2 diabetes genes CDKAL1 and HHEX/IDE are associated with decreased pancreatic beta-cell function. Diabetes 2007; 56: 3101–3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubeda M, Rukstalis JM, Habener JF: Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 activity protects pancreatic beta cells from glucotoxicity. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 28858–28864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei FY, Nagashima K, Ohshima T et al: Cdk5-dependent regulation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Nat Med 2005; 11: 1104–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinthorsdottir V, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I et al: A variant in CDKAL1 influences insulin response and risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 770–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice AM, Hennig BJ, Fulford AJ: Evolutionary origins of the obesity epidemic: natural selection of thrifty genes or genetic drift following predation release? Int J Obes (Lond) 2008; 32: 1607–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Ogawa A, Miyashita H et al: Positive natural selection of TRIB2, a novel gene that influences visceral fat accumulation, in East Asia. Hum Genet 2013; 132: 201–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre P, Chinetti G, Fruchart JC, Staels B: Sorting out the roles of PPAR alpha in energy metabolism and vascular homeostasis. J Clin Invest 2006; 116: 571–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersten S, Seydoux J, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, Desvergne B, Wahli W: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha mediates the adaptive response to fasting. J Clin Invest 1999; 103: 1489–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Cook WS, Qi C, Yeldandi AV, Reddy JK, Rao MS: Defect in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha-inducible fatty acid oxidation determines the severity of hepatic steatosis in response to fasting. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 28918–28928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone TC, Weinheimer CJ, Kelly DP: A critical role for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) in the cellular fasting response: the PPARalpha-null mouse as a model of fatty acid oxidation disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999; 96: 7473–7478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy JK, Hashimoto T: Peroxisomal beta-oxidation and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha: an adaptive metabolic system. Annu Rev Nutr 2001; 21: 193–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt SA, Spring A, Hiebsch C et al: The "Tree Against Hunger". Enset-based Agricultural Systems in Ethiopia. Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ehret C: On the antiquity of agriculture in Ethiopia. J Afr Hist 1979; 20: 161–177. [Google Scholar]

- Ge RL, Simonson TS, Cooksey RC et al: Metabolic insight into mechanisms of high-altitude adaptation in Tibetans. Mol Genet Metab 2012; 106: 244–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonson TS, Yang Y, Huff CD et al: Genetic evidence for high-altitude adaptation in Tibet. Science 2010; 329: 72–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin MJ, Kanaya AM, Krauss RM: Polymorphisms in the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha gene are associated with levels of apolipoprotein CIII and triglyceride in African-Americans but not Caucasians. Atherosclerosis 2008; 198: 313–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura R, Takahashi N, Murota K et al: Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha (PPARalpha) suppresses postprandial lipidemia through fatty acid oxidation in enterocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011; 410: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesfaye F: Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Ethiopia: The rural–urban gradient, PhD thesis Umea: Umeå University, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Misganaw A, Mariam DH, Araya T, Ayele K: Patterns of mortality in public and private hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani L, Kivisild T, Tarekegn A et al: Ethiopian genetic diversity reveals linguistic stratification and complex influences on the Ethiopian gene pool. Am J Hum Genet 2012; 91: 83–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beleza S, Santos AM, McEvoy B et al: The timing of pigmentation lightening in Europeans. Mol Biol Evol 2013; 30: 24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj T, Kuchroo M, Replogle JM, Raychaudhuri S, Stranger BE, De Jager PL: Common risk alleles for inflammatory diseases are targets of recent positive selection. Am J Hum Genet 2013; 92: 517–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakob B, Deribe K, Davey G: High levels of misconceptions and stigma in a community highly endemic for podoconiosis in southern Ethiopia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2008; 102: 439–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tora A, Davey G, Tadele G: A qualitative study on stigma and coping strategies of patients with podoconiosis in Wolaita zone, Southern Ethiopia. Int Health 2011; 3: 176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekola F, Bull S, Farsides B et al: Impact of social stigma on the process of obtaining informed consent for genetic research on podoconiosis: a qualitative study. BMC Med Ethics 2009; 10: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.