Abstract

Background

We recently reported 5 highly specific physical signs associated with death within 3 days among cancer patients that may aid the diagnosis of impending death. In this study, we examined the frequency and onset of an additional 52 bedside physical signs and their diagnostic performance for impending death.

Methods

We enrolled 357 consecutive patients with advanced cancer admitted to acute palliative care units at two tertiary care cancer centers. We systematically documented 52 physical signs every 12 hours from admission to death or discharge. We examined the frequency and median time of onset of each sign from death backwards, and calculated their likelihood ratios (LRs) associated with death in 3 days.

Results

203/357 (57%) patients died at the end of the admission. We identified 8 physical signs that were highly diagnostic of impending death. These signs occurred in 5-78% of patients in the last 3 days of life, had a late onset, and had a high specificity (>95%) and high positive LR for death within 3 days, including non-reactive pupils (positive LR 16.7, 95% confidence interval 14.9-18.6), decreased response to verbal stimuli (8.3, 7.7-9), decreased response to visual stimuli (6.7, 6.3-7.1), inability to close eyelids (13.6, 11.7-15.5), drooping of nasolabial fold (8.3, 7.7-8.9), hyperextension of neck (7.3, 6.7-8), grunting of vocal cords (11.8, 10.3-13.4), and upper gastrointestinal bleed (10.3, 9.5-11.1).

Conclusion

We identified 8 highly specific physical signs associated with death within 3 days in cancer patients. These signs may inform the diagnosis of impending death.

Keywords: diagnosis, neoplasms, palliative care, physical examination, sensitivity, signs, specificity

Introduction

As patients approach the last days of their lives, they experience a multitude of physiological changes affecting their neurocognitive, cardiovascular, respiratory, muscular function.1 These bodily changes may be observed at the bedside, and may assist clinicians in establishing the diagnosis of impending death (i.e. death within days). The ability to make the diagnosis of impending death with confidence is of great importance to clinicians who attend to patients at the end-of-life, because it could affect their communication with patients and families, and inform complex decision making such as discontinuation of investigations and aggressive treatments, discharge planning and enrollment on clinical care pathways.2, 3

There has been a paucity of studies examining diagnostic signs of impending death. A majority of the studies on this topic started monitoring patients when they were recognized as “actively dying”, which could potentially result in a biased population and over-estimation of the frequency of these physical signs.4, 5 Recognizing this limitation, we recently conducted the Investigating the Process of Dying study, a prospective longitudinal observational study that systematically documented an array of clinical signs on a 12 hourly basis in consecutive patients from the time of admission to an acute palliative care unit (APCU).6 Of the 10 target signs, we identified 5 signs (i.e. pulselessness of radial artery, decreased urine output, Cheyne Stokes breathing, respiration with mandibular movement, and death rattle) that occurred only in the last days of life, and were highly predictive of an impending death within 3 days. In this study, we report on the frequency and onset of an additional 52 bedside physical signs and their diagnostic performance for impending death.

Methods

Study Setting and Criteria

This study is a planned secondary analysis of the Investigating the Process of Dying Study to identify physical signs of impending death. The methods has been reported in detail previously.6 Briefly, we enrolled consecutive patients with a diagnosis of advanced cancer who were ≥18 years of age and admitted to the APCUs at MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) in the United States between 4/5/2010-7/6/2010 and Barretos Cancer Hospital (BCH) in Brazil between 1/27/2011-6/1/2011. The Institutional Review Boards at both institutions approved this study. Waiver of consent for patient participation was endorsed to minimize distress during the consent process and to ensure that we could collect data on consecutive patients. All nurses who participated in this study signed the informed consent prior to enrollment.

APCU was the setting of choice for this study because of (1) the relatively high mortality rate, (2) the presence of clinical staff 24 hours a day, and importantly, (3) the experience of APCU nurses in providing care to patients in the last days of life, and their commitment to complete the study assessments every shift. Patients with advanced cancer were admitted to APCUs for symptom control and/or transition of care at the end-of-life.7 Both participating APCUs are situated within tertiary care cancer centers and provide interprofessional symptom management and psychosocial care, active management of acute complications, and discharge planning.8

Data Collection

We selected a list of clinical signs to be documented every 12 hours from admission until death or discharge based on a literature review of published studies, review articles, and educational materials.1, 4, 9-11 The final list included an array of 62 signs that systematically cover the neurological, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, gynecological, muscular and integumentary systems. Ten of these signs were selected as target signs based on their prevalence in the literature (i.e. apnea periods, Cheyne Stokes breathing, death rattle, dysphagia of liquids, decreased level of consciousness, palliative performance scale ≤20%, peripheral cyanosis, pulselessness of radial artery, respiration with mandibular movement, and decreased urine output) and had been reported previously.6 This study focuses on the remaining 52 physical signs.

We collected baseline patient demographics on admission. All nurses who participated in this study worked full time in palliative care and were experienced in providing care at the end-of-life. All nurses attended an orientation session to review the study objectives and data collection forms, with particular emphasis on physical signs not commonly described, such as grunting of vocal cords and drooping of nasolabial fold. Moreover, the principal investigators and charge nurses provided longitudinal support during the study by reviewing the forms on a daily basis to ensure they were complete and accurate, and provided education to the nurses on an as needed basis. The two study sites had weekly video conference to ensure data were collected systematically and accurately. The study forms were translated to Portuguese to facilitate data collection in Brazil and back-translated to ensure accuracy of translation. Clinical nurses completed standardized data collection forms independently of prior assessments. The 12-hour period was chosen based on the duration of nursing shift.

Table 1 includes a detailed description and coding for the 52 clinical signs. A majority of the signs were marked as either absent or present during the past 12 hours based on the nurses’ clinical observation (e.g. drooping of nasolabial fold, respiration with mandibular movement). A grading system was used for the remaining signs (e.g., myoclonus). Delirium was documented using the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS) every 12 hours. The MDAS is validated for delirium screening in cancer patients. It is comprised of 10 items each with a score between 0 (normal) and 3 (worst). A total score >13/30 suggests delirium.12 We also documented vital signs including heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature and oxygen saturation. The values were routinely collected for all admitted patients unless ordered otherwise by the attending physician.

Table 1. Definition of clinical signs.

| Variable (definition) | Criteria for negative sign |

Criteria for positive sign |

|---|---|---|

| Vitals | ||

| Heart rate (beats/min) | ≤100 | >100 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | ≤20 | >20 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | ≥100 | <100 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | ≥60 | <60 |

| Temperature (°C) | ≥36 | <36 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | ≥90 | <90 |

| Supplemental oxygen use | Absent | Present |

| Nervous System | ||

| Memorial delirium rating scale | 0-13 | ≥13 |

| Agitation/purposeless movements | None; rarely | Obvious; severe |

| Decreased level of consciousness | Absent | Present |

| Non-reactive pupils | Absent | Present |

| Decreased response to verbal stimuli | Absent | Present |

| Decreased response to visual stimuli | Absent | Present |

| Decreased speech | Absent | Present |

| Motor abnormality: Tremors | Absent | Present |

| Motor abnormality: Weakness | Absent | Present |

| Myoclonus | None | Mild fasciculations involving face/distal extremities; marked movements of the face/limbs; severe movements involving limbs and trunk |

| Seizures | Absent | Present |

| Head and Neck | ||

| Inability to close eyelids | Absent | Present |

| Drooping of nasolabial fold (decrease in prominence/visibility of the nasolabial fold) |

Absent | Present |

| Hyperextension of neck | Absent | Present |

| Epistaxis | None | Streaks; teaspoon; tablespoon |

| Thrush | Absent | Present |

| Cardiovascular | ||

| Mottling (stasis, purplish discoloration of extremities) |

None | Toes; feet; up to knees |

| Peripheral edema | None | Up to ankle; up to knee; anasarca |

| Capillary refill >3 s | Absent | Present |

| Decreased heart sounds | Absent | Present |

| Respiratory | ||

| Grunting of vocal cords (sound produced predominantly on expiration, related to vibrations of the vocal cords) |

Absent | Present |

| Irregular breathing pattern | Absent | Present |

| Decreased breath sounds | Absent | Present |

| Tachypnea | ≤20 | 21-30; 31-40; >40 |

| Use of accessory muscles | Absent | Present |

| Hemoptysis | None | Streaks; teaspoon; tablespoon |

| Inability to clear secretions | Absent | Present |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Upper gastrointestinal bleed | None | <20ml; >20ml; hemodynamic Δ |

| Lower gastrointestinal bleed (hematochezia, melena) |

None | <20ml; >20ml; hemodynamic Δ |

| Dysphagia of solids | Absent | Present |

| Meals left over | None; <half | >half; entire meal |

| Ascites | Absent | Present |

| Bowel sounds | Within normal limits; hyperactive |

Hypoactive; absent |

| Fecal incontinence | Absent | Present |

| Genitourinary | ||

| Voiding difficulties | Normal | Abnormal; diaper; urinary catheter |

| Urinary incontinence | Absent | Present |

| Vaginal bleed | Absent | Present |

| Vaginal discharge | Absent | Present |

| Hematuria | None | Hematuria but no clots; blood clots |

| Integumentary | ||

| Skin turgor | Good <1s recoil | Fair 1-2s recoil; poor >2s recoil |

| Cool/cold extremities | None | Toes; feet; up to knees |

| Skin moist or diaphoretic | Absent | Present |

| Pressure ulcer | Absent | Present |

| Cool skin temperature | Absent | Present |

| Sweating | None | Limited; diffuse; drenching |

Survival from time of APCU admission was collected from institutional databases and electronic health records.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed the data using the same methodology in previous reports.6, 13 Our pre-planned sample size was a combined total of 200 deaths in the 2 study sites as stated previously.6 This analysis was planned based on the combined data a priori. Briefly, we dichotomized all the variables into “absent” or “present” (see Table 1). Pre-defined cutoffs were used for continuous variables (e.g. vital signs). For the patients who died in the APCUs, we calculated the frequency of each sign from the time of death backwards. We also determined the median duration between first documentation of each sign and death using the Kaplan Meier Method, conditional on observation of that particular sign or symptom. In time-to-event analysis, patients were left censored if they entered the APCU with the sign already present.

To determine the diagnostic utility of each sign, we computed the sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (LR) and negative LR for death within 3 days in 357 patients.6, 13,14 Positive LRs indicate how many fold the sign of interest appeared in patients who died within 3 days compared to patients who did not die within 3 days. Positive LRs of >5 and >10 suggest good and excellent discriminatory test performance, respectively.15 The last 3-days was chosen as the cutoff for impending death because our previous study showed emergence of many of the signs of impending death during this period, and that knowing a patient is in the last 3 days of life could impact many medical decisions such as hospital discharge, discontinuation of prescription medications, artificial nutrition and use of life support measures. To account for the multiple observations in each patient, we randomly sampled our data with one observation per patient to construct a data set with independent samples, and then calculated the sensitivity, specificity, positive LR and negative LR for the resampled dataset. We repeated this resampling algorithm 100x to obtain the average and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each statistic.

We also examined the univariate odds ratios (ORs) using a similar re-sampling methodology. ORs are complementary to LRs because they provide an estimate of the strength of association between impending death and the physical signs. We also determined the prevalence (i.e. pre-test probability) of death within 3 days. We selected the 7 neurological signs with the positive LR >5 for inclusion in a multivariate logistic regression model with backward selection using a similar re-sampling strategy with 500 repetitions. Upper gastrointestinal bleed was excluded from the model because of its low frequency. We examined the goodness of fit of the model using the Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic, where a P-value of >0.05 indicates good fit.16, 17

The Statistical Analysis System (SAS version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) was used for statistical analysis. A P-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The patient demographics have been reported in a previous study.6 In brief, the average age was 58 (range 18-88), 195 (55%) were female, and 233 (65%) were of Hispanic origin, and 101 (28%) had a diagnosis of gastrointestinal cancer. The median duration of the APCU admission was 6 days (interquartile range 4-9 days).

Frequency and Onset of Clinical Signs

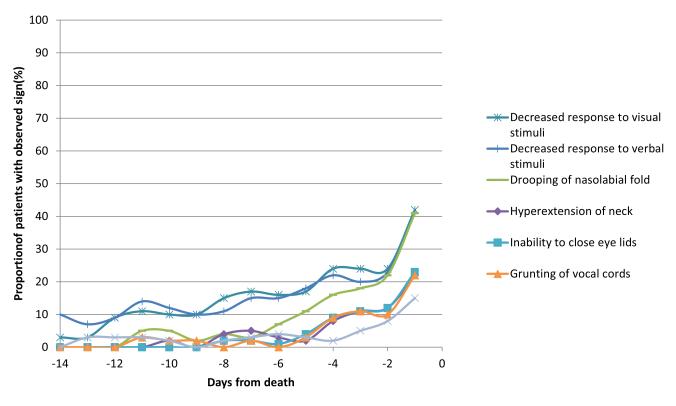

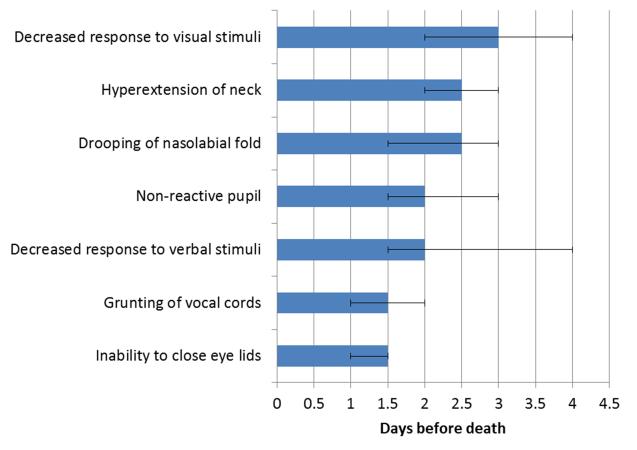

The frequency and median onset of the 52 physical signs are shown in Table 2. Figure 1 shows the frequency over the last 14 days of life for 7 selected neurological signs based on their high diagnostic performance. These 7 signs had a late median onset within the last 3 days of life (Figure 2).

Table 2. Frequency, onset, odds ratio, sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive likelihood ratio for 52 physical signs in 3 days (n=357)a.

| Sign | Prevalence of sign in last 3 days of life, N (%)b |

Median onset, days from death (95% CI) |

Univariate odds ratio (95% CI) |

Sensitivityc (95% CI) |

Specificityc (95% CI) |

Negative Likelihood Ratioc (95% CI) |

Positive Likelihood Ratioc (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitals | |||||||

| Diastolic blood pressure <60mmHg | 76 (62) | 2.5 (2.0-3.5) | 4.5 (2.6-10.2) | 19.3 (18.7-19.9) | 94.9 (94.6-95.2) | 0.85 (0.84-0.86) | 4.1 (3.8-4.4) |

| Heart rate >100/minute | 130 (92) | 8.5 (6.0-11.5) | 2.1 (1.4-2.9) | 53.1 (52.4-53.8) | 65 (64.5-65.5) | 0.72 (0.71-0.74) | 1.5 (1.5-1.6) |

| Oxygen saturation <90% | 107 (90) | 5.5 (4.0-7.0) | 3.9 (2.6-6.1) | 40.5 (39.7-41.2) | 86 (85.5-86.4) | 0.69 (0.68-0.7) | 3 (2.8-3.1) |

| Respiratory rate >20/minute | 102 (72) | 4.5 (3.5-5.5) | 2.5 (1.7-4.3) | 24.1 (23.5-24.7) | 88.6 (88.2-89) | 0.86 (0.85-0.87) | 2.2 (2.1-2.3) |

| Supplemental oxygen use | 170 (89) | 6.5 (4.5-10.5) | 6.8 (0.8-27) | 1.9 (1.6-2.2) | 99.1 (99-99.3) | 0.99 (0.99-0.99) | 2.9 (2.5-3.4) |

| Systolic blood pressure <100mmHg | 112 (82) | 4.0 (3.0-6.5) | 4.1 (2.7-6.7) | 34.9 (34.3-35.6) | 88.2 (87.8-88.6) | 0.74 (0.73-0.75) | 3.1 (2.9-3.2) |

| Temperature <36C | 81 (60) | 5.5 (3.5-7.5) | 1.2 (0.7-2.2) | 18.2 (17.6-18.8) | 85.2 (84.7-85.6) | 0.96 (0.95-0.97) | 1.3 (1.2-1.3) |

| Nervous System | |||||||

| Agitation/purposeless movements | 53 (36) | 3.5 (2.5-4.0) | 2.2 (1.4-4.6) | 10.9 (10.5-11.2) | 94.9 (94.6-95.2) | 0.94 (0.93-0.94) | 2.4 (2.2-2.5) |

| Decreased level of consciousness | 186 (97) | 7.0 (5.5-8.5) | 5.6 (4.2-7.5) | 74 (73.4-74.5) | 66.1 (65.7-66.6) | 0.39 (0.39-0.4) | 2.2 (2.2-2.2) |

|

Decreased response to verbal

stimuli |

118 (69) | 2.0 (1.5-4.0) | 10 (5.2-23.8) | 30 (29.4-30.5) | 96 (95.8-96.3) | 0.73 (0.72-0.74) | 8.3 (7.7-9) |

|

Decreased response to visual

stimuli |

121 (70) | 3.0 (2.0-4.0) | 7.6 (5-16.1) | 31.9 (31.4-32.4) | 94.9 (94.6-95.1) | 0.72 (0.71-0.72) | 6.7 (6.3-7.1) |

| Decreased speech | 143 (79) | 4.0 (3.0-6.0) | 6.9 (4.8-10.9) | 42.6 (42-43.2) | 90.2 (89.8-90.5) | 0.64 (0.63-0.64) | 4.4 (4.3-4.6) |

| Memorial Delirium Rating Scale >13 |

105 (89) | 12 (11.0-13.0) | 7.7 (4.8-12) | 66.3 (65.6-67) | 80.5 (79.9-81.1) | 0.42 (0.41-0.43) | 3.5 (3.4-3.6) |

| Motor abnormality: Tremors | 47 (32) | 7.0 (4.0-9.0) | 2.6 (1.3-5.9) | 9 (8.7-9.4) | 96.8 (96.5-97) | 0.94 (0.94-0.94) | 3.2 (2.9-3.5) |

| Motor abnormality: Weakness | 168 (89) | 31.0 (11.0-50.5) | 1 (0.7-1.3) | 65.6 (65-66.2) | 34.6 (34.1-35.1) | 1 (0.98-1.03) | 1 (1-1) |

| Myoclonus | 63 (42) | 4.0 (3.5-6.5) | 2.4 (1.3-5.9) | 14.4 (13.9-14.9) | 93.2 (92.9-93.5) | 0.92 (0.91-0.93) | 2.3 (2.1-2.5) |

| Non-reactive pupils | 53 (38) | 2.0 (1.5-3.0) | 13.7 (6.1-89.9) | 15.3 (14.9-15.7) | 99 (98.8-99.1) | 0.86 (0.85-0.86) | 16.7 (14.9-18.6) |

| Seizures | 5 (4) | 2.5 (0.5-28.0) | 4.4 (0.5-8.2) | 0.7 (0.6-0.8) | 99.7 (99.6-99.7) | 1 (1-1) | 2.6 (2.2-3) |

| Head and Neck | |||||||

| Drooping of nasolabial fold | 137 (78) | 2.5 (1.5-3.0) | 9.4 (6-21.1) | 33.7 (33.2-34.3) | 95.5 (95.3-95.8) | 0.69 (0.69-0.7) | 8.3 (7.7-8.9) |

| Epistaxis | 7 (5) | 2.8 (0.5-4.5) | 1.5 (0.3-6.2) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 99.4 (99.3-99.5) | 1 (1-1) | 1.9 (1.5-2.4) |

| Hyperextension of neck | 73 (46) | 2.5 (2.0-3.0) | 7.6 (4.4-16.9) | 21.2 (20.6-21.7) | 96.7 (96.5-96.9) | 0.82 (0.81-0.82) | 7.3 (6.7-8) |

| Inability to close eyelids | 93 (57) | 1.5 (1.0-1.5) | 11.3 (5.5-36.5) | 21.4 (20.9-21.8) | 97.9 (97.7-98.1) | 0.8 (0.8-0.81) | 13.6 (11.7-15.5) |

| Thrush | 29 (21) | 4.0 (3.0-7.0) | 0.9 (0.5-2.1) | 6.6 (6.3-6.9) | 93.6 (93.3-93.9) | 1 (0.99-1) | 1.1 (1-1.2) |

| Cardiovascular | |||||||

| Capillary refill >3 s | 155 (87) | 7.0 (4.5-14.0) | 4.1 (2.7-5.9) | 47.3 (46.6-48) | 82.4 (81.9-82.8) | 0.64 (0.63-0.65) | 2.7 (2.6-2.8) |

| Decreased heart sounds | 76 (48) | 2.5 (1.0-3.5) | 3.6 (2-6.8) | 16.2 (15.7-16.7) | 94.7 (94.4-95) | 0.89 (0.88-0.89) | 3.4 (3.1-3.8) |

| Mottling | 71 (46) | 2.5 (1.5-3.5) | 4.6 (2.9-12.1) | 17.1 (16.6-17.6) | 95.8 (95.5-96) | 0.87 (0.86-0.87) | 4.4 (4.1-4.6) |

| Peripheral edema | 178 (94) | 13.5 (8.5-30.0) | 2 (1.5-3) | 68.8 (68.2-69.4) | 47.9 (47.4-48.4) | 0.65 (0.64-0.67) | 1.3 (1.3-1.3) |

| Respiratory | |||||||

| Decreased breath sounds | 100 (61) | 8.5 (7.0-10.5) | 1.3 (1-1.7) | 40.8 (40.3-41.3) | 65.5 (65-66) | 0.91 (0.89-0.92) | 1.2 (1.2-1.2) |

| Grunting of vocal cords | 86 (54) | 1.5 (1.0-2.0) | 10.7 (4.6-32.5) | 19.5 (19-19.9) | 97.9 (97.7-98.1) | 0.82 (0.82-0.83) | 11.8 (10.3-13.4) |

| Hemoptysis | 10 (8) | 4.0 (1.5-31.5) | 3.1 (1-16.3) | 2.8 (2.6-3) | 99.1 (99-99.2) | 0.98 (0.98-0.98) | 4.7 (3.9-5.5) |

| Inability to clear secretions | 155 (87) | 3.5 (2.5-4.5) | 4.8 (2.9-6.9) | 46.1 (45.6-46.7) | 84.9 (84.5-85.3) | 0.64 (0.63-0.64) | 3.1 (3-3.2) |

| Irregular breathing pattern | 109 (65) | 4.5 (3.0-7.0) | 4.7 (3.1-8.2) | 38 (37.4-38.5) | 88.6 (88.2-89) | 0.7 (0.69-0.71) | 3.4 (3.3-3.6) |

| Tachypnea | 129 (76) | 4.5 (3.5-6.0) | 1.8 (1.2-2.7) | 26.8 (26.2-27.4) | 83.1 (82.7-83.5) | 0.88 (0.87-0.89) | 1.6 (1.6-1.7) |

| Use of accessory muscles | 135 (77) | 3.5 (2.5-5.0) | 4.7 (3.1-6.9) | 41.4 (40.7-42) | 86.7 (86.3-87.1) | 0.68 (0.67-0.68) | 3.2 (3.1-3.3) |

| Gastrointestinal | |||||||

| Ascites | 50 (35) | 4.5 (3.0-7.0) | 1.2 (0.7-1.9) | 14.7 (14.3-15.1) | 87.5 (87.1-87.8) | 0.98 (0.97-0.98) | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) |

| Decreased or absent bowel sounds | 49 (36) | 3.0 (2.0-3.0) | 2 (1.3-4.2) | 12.4 (12-12.7) | 93.5 (93.3-93.8) | 0.94 (0.93-0.94) | 2 (1.9-2.2) |

| Dysphagia of solids | 118 (96) | 11.0 (6.0-18.5) | 2.5 (1.9-3.6) | 50.1 (49.4-50.8) | 71.9 (71.5-72.4) | 0.7 (0.68-0.71) | 1.8 (1.8-1.9) |

| Fecal incontinence | 84 (57) | 4.5 (3.0-6.5) | 2.4 (1.5-4.1) | 28.2 (27.7-28.7) | 86.1 (85.7-86.4) | 0.83 (0.83-0.84) | 2.1 (2-2.1) |

| Lower gastrointestinal bleed | 8 (6) | 12.0 (2.5-46.5) | 1.5 (0.7-3.9) | 2.9 (2.7-3) | 98.1 (97.9-98.2) | 0.99 (0.99-0.99) | 1.8 (1.5-2) |

| Meals >half left over | 183 (95) | 7.5 (5.0-9.5) | 3.5 (2.6-5.3) | 81.1 (80.6-81.5) | 45.7 (45.2-46.2) | 0.41 (0.4-0.42) | 1.5 (1.5-1.5) |

| Upper gastrointestinal bleed | 6 (5) | 5.5 (0.5-17.0) | 10.9 (2.6-18.5) | 2.9 (2.8-3) | 99.7 (99.6-99.7) | 0.97 (0.97-0.98) | 10.3 (9.5-11.1) |

| Genitourinary | |||||||

| Hematuria | 25 (19) | 3.5 (2.0-4.5) | 2.9 (1.1-9.6) | 5.9 (5.6-6.1) | 97.8 (97.6-97.9) | 0.96 (0.96-0.97) | 3.4 (2.7-4.1) |

| Urinary incontinence | 124 (72) | 6.0 (4.5-10.5) | 1.9 (1.4-2.4) | 47.9 (47.4-48.5) | 67.2 (66.8-67.6) | 0.78 (0.77-0.79) | 1.5 (1.4-1.5) |

| Vaginal bleed | 5 (7) | 13.5 (3.0-.) | 1.9 (0.2-6) | 3.2 (2.8-3.5) | 97.8 (97.6-98) | 0.99 (0.99-1) | 2.4 (1.8-3) |

| Vaginal discharge | 8 (11) | 3.0 (0.5-34.0) | 2 (0.6-6.5) | 4.1 (3.7-4.4) | 97.7 (97.5-97.9) | 0.98 (0.98-0.99) | 2.5 (2-2.9) |

| Voiding difficulties | 190 (97) | 11.5 (9.0-31.0) | 5.2 (3.8-7.6) | 80.5 (80-80.9) | 56.7 (56.3-57.1) | 0.35 (0.34-0.35) | 1.9 (1.8-1.9) |

| Integumentary | |||||||

| Cool skin temperature | 59 (40) | 3.0 (2.0-6.0) | 4.8 (2.2-13.5) | 13.6 (13.2-14) | 96.8 (96.6-97) | 0.89 (0.89-0.9) | 4.9 (4.4-5.3) |

| Cool/cold extremities | 151 (84) | 7.5 (5.5-9.0) | 2.5 (1.7-3.2) | 47.9 (47.4-48.5) | 71.4 (70.8-72) | 0.73 (0.72-0.74) | 1.7 (1.7-1.7) |

| Pressure ulcer | 65 (47) | 7.5 (4.5-13.0) | 1.3 (0.9-1.9) | 16.6 (16.2-17) | 86.5 (86.1-86.9) | 0.97 (0.96-0.97) | 1.3 (1.2-1.3) |

| Skin moist or diaphoretic | 9 (8) | 3.5 (3.0-6.0) | 1.1 (0.2-10.8) | 1.3 (1.1-1.4) | 99.1 (99-99.2) | 1 (0.99-1) | 2.3 (1.9-2.7) |

| Skin turgor recoil >=1s | 198 (99) | 40.0 (21.0-.) | 1.8 (1.2-2.6) | 85.6 (85.2-86) | 23.8 (23.3-24.3) | 0.61 (0.59-0.63) | 1.1 (1.1-1.1) |

| Sweating | 110 (66) | 3.5 (2.5-5.5) | 2.4 (1.2-3.6) | 20.9 (20.3-21.5) | 89.6 (89.2-89.9) | 0.88 (0.88-0.89) | 2.1 (2-2.2) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval

positive LRs >5 are highlighted in bold.

any occurrence of the sign of interest within the last 3 days of life among patients who died in the APCU.

sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (LR), and negative LR were computed for each sign for death within 3 days using data from all 357 patients. To account for the multiple observations for each patient, we re-sampled our data by randomly selecting one observation from each subject to construct a data set with independent samples, and then calculated the sensitivity, specificity, positive LR and negative LR for the re-sampled dataset. We repeated this re-sampling algorithm 100 times to obtain the average and 95% confidence interval for each statistic.

Figure 1. Frequency of 7 neurological signs of impending death among 203 patients with advanced cancer who died in an acute palliative care unit.

The frequency of these signs increased over the last few days.

Figure 2. Onset of 7 neurological signs of impending death.

The median onset (95% confidence interval) was ≤3 days before death for all 7 signs.

Likelihood Ratios for Death in 3 days

The prevalence (i.e. pretest probability) of death in 3 days was 38% (95% CI 19%-57%), for our cohort. Table 2 shows the sensitivity, specificity, positive LR and negative LR associated with death in 3 days for the 52 physical signs. Eight of these signs had high specificity (95% or higher) and a high positive LR >5, including non-reactive pupils, decreased response to verbal stimuli, decreased response to visual stimuli, inability to close eyelids, drooping of nasolabial fold, hyperextension of neck, grunting of vocal cords, and upper gastrointestinal bleed. The multivariate analysis revealed that decreased response to verbal stimuli and drooping of nasolabial fold were significantly associated with death in 3 days (Table 3). The median P-value for the Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic was 0.54, indicating good calibration.

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression for death in 3 days.

| Sign | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased response to verbal stimuli | 6.61 (2.49-23.17) | 0.0004 |

| Drooping of nasal labial fold | 6.51 (2.67-20.07) | 0.0001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval

DISCUSSION

We previously reported 5 physical signs that were highly diagnostic of impending death. This study systematically examined a comprehensive list of signs that represent multiple organ systems, and identified 8 additional highly specific physical signs for impending death in 3 days. The presence of these signs was associated with a high likelihood of death within 3 days, although their absence cannot rule out that the patient will die shortly because of their low sensitivity. The use of these bedside physical signs individually or in combination may assist clinicians to make the diagnosis of impending death.

With the exception of upper gastrointestinal bleed, all the signs identified in this study were related to deterioration in neurocognitive (i.e. non-reactive pupils, decreased response to verbal stimuli, decreased response to visual stimuli) and neuromuscular (i.e. inability to close eyelids, drooping of nasolabial fold, hyperextension of neck, and grunting of vocal cords) function. In addition, 3 of 5 the physical signs identified in our previous study (i.e. Cheyne Stokes breathing, respiration with mandibular movement, and death rattle) were also related to altered neurological status. Importantly, all 10 of these highly specific neurological signs occurred relatively late, with a median onset of 3 days before death. The high specificity suggests that few patients who did not die in 3 days were observed to have these signs. These signs were commonly observed in the last 3 days of life, with a frequency between 38% and 78% of patients. Our findings highlight the progressive decline in neurological function is associated with the dying process.

Upper GI bleed in patients admitted to APCUs also had a high positive LR for impending death. Understandingly, hematemesis is a life-threatening complication, and could lead to hemodynamic instability resulting in death acutely. Because the frequency of upper GI bleed was low (5%) in the last days of life, further studies are needed to confirm the diagnostic utility of this sign.

Multivariate analysis identified 2 physical signs (i.e. decreased response to verbal stimuli and drooping of nasolabial fold) were independently significant. However, the other physical signs with high positive LR, when present, are still helpful in the diagnosis of impending death. This is particularly because patients often do not present with all the physical signs at the same time.

The positive LRs for the 8 diagnostic signs ranged between 5 and 16.7. The positive LR can be easily applied in the clinical setting to facilitate the diagnosis of impending death using either a formula or nomogram. For instance, the pre-test probability to die within 3 days after admission to our APCUs was 38%. The presence of grunting of vocal cords (positive LR 11.8) in a patient results in a post-test probability of 88% of death in next 3 days. Given the high likelihood of impending death, the clinician may recommend discontinuation of bloodwork and selected medications and hold hospital discharge after a discussion with the patient and/or her family.

Although some of signs identified here have been described anecdotally in review articles and books,1, 4, 10, 11 this is the first study to systematically characterize their frequencies, onset, LRs and ORs, thus allowing clinicians to differentiate their relative importance and utility for the diagnosis of impending death. For instance, the positive LR for diastolic blood pressure <60mmHg, mottling, hemoptysis and cool skin temperature were between 4-5 (Table 2). Although these signs may be associated with impending death, they had lower diagnostic utility for impending death compared to the 8 signs identified above. Interestingly, many other signs such as delirium, dysphagia, incontinence that occur commonly at the end-of-life were not diagnostic, likely because they had an earlier onset, and thus less useful to inform us of imminent death. We also identified many signs such as epistaxis, myoclonus and thrush were not associated with impending death, providing good internal control.

This study has several limitations. First, we only included cancer patients admitted to APCUs who often have severe symptoms.18 The frequency, onset and utility of the signs of impending death may differ in other healthcare settings and patient populations, and would need to be further examined. Second, the mortality rates of the two APCUs differed significantly. This is related to healthcare system differences—patients in Brazil could stay in the hospital for longer periods of time compared to those in the US. Importantly, the two APCUs have similar palliative care practices, and the investigators from each site have also visited each other. Despite the different mortality rates in the two APCUs, we found comparable specificities and sensitivities for the signs between the 2 participating institutions, which further strengthen our results and their generalizability. Third, the inter-rater reliability of these signs would also need to be assessed in future studies. We only documented the signs every 12 hours which limits the resolution of data to identify the median onset. Fourth, we examined a large number of clinical signs in a relatively small number of patients. Our findings should thus be considered preliminary until validated in future studies. The physical signs reported here, in conjunction with those reported previously,6 may pave the way towards development and validation of a bedside diagnostic tool for impending death.

In summary, this study identified 8 physical signs with high specify and positive likelihood ratio for impending death within 3 days. Upon further validation, the presence of these “tell-tale” signs would suggest that patients have entered the final phase of life. Taken together with the 5 physical signs identified earlier, these objective bedside signs may assist clinicians, family members and researchers to recognize when the patient has entered the final days of life.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This research is supported in part by a University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant (CA 016672), which provided the funds for data collection at both study sites. EB is supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R01NR010162-01A1, R01CA122292-01, and R01CA124481-01.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

No potential conflict of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Plonk WM, Jr., RM Arnold. Terminal care: the last weeks of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(5):1042–54. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hui D, Con A, Christie G, Hawley PH. Goals of care and end-of-life decision making for hospitalized patients at a canadian tertiary care cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(6):871–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellershaw J, Ward C. Care of the dying patient: the last hours or days of life. BMJ. 2003;326(7379):30–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morita T, Ichiki T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S. A prospective study on the dying process in terminally ill cancer patients. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 1998;15(4):217–22. doi: 10.1177/104990919801500407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hwang IC, Ahn HY, Park SM, Shim JY, Kim KK. Clinical changes in terminally cancer patients and death within 48 h: when should we refer patients to a separate room? Support Care Cancer. 2012;21(3):835–40. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1587-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui D, Dos Santos R, Chisholm G, Bansal S, Silva TB, Kilgore K, et al. Clinical Signs of Impending Death in Cancer Patients. Oncologist. 2014;19(6):681–7. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hui D, Elsayem A, Li Z, De La Cruz M, Palmer JL, Bruera E. Antineoplastic therapy use in patients with advanced cancer admitted to an acute palliative care unit at comprehensive cancer center: a simultaneous care model. Cancer. 2010;116(8):2036–43. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hui D, Elsayem A, Palla S, De La Cruz M, Li Z, Yennurajalingam S, et al. Discharge outcomes and survival of patients with advanced cancer admitted to an acute palliative care unit at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(1):49–57. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emanuel LL, Ferris FD, von Gunten CF. [accessed June 24, 2014];Module 6: Last Hours of Living. Available from URL: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/cancerlibrary/epeco/selfstudy/module-6.

- 10.Ferris FD. Last hours of living. Clin Geriatr Med. 2004;20(4):641–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2004.07.011. vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lichter I, Hunt E. The last 48 hours of life. J Palliat Care. 1990;6(4):7–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Roth A, Smith MJ, Cohen K, Passik S. The Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(3):128–37. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00316-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruera S, Chisholm G, Santos RD, Crovador C, Bruera E, Hui D. Variations in Vital Signs in the Last Days of Life in Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.10.019. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parshall MB. Unpacking the 2 × 2 table. Heart Lung. 2013;42(3):221–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Diagnostic tests 4: likelihood ratios. BMJ. 2004;329(7458):168–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7458.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW. A Review of Goodness of Fit Statistics for Use in the Development of Logistic Regression Models. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;115(1):92–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Goodness of fit tests for the multiple logistic regression model. Commun Stat. 1980;A9(10):1043–69. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970515)16:9<965::aid-sim509>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, Berger A, Zhukovsky DS, Palla S, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1054–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]