Abstract

Background

Supportive oncology practice can be enhanced by integrating brief and validated electronic patient-reported outcome (ePRO) assessment into the electronic health record (EHR) and clinical workflow.

Methods

636 women receiving gynecologic oncology outpatient care received instructions to complete clinical assessments through Epic MyChart, the EHR patient communication portal. PROMIS computer adaptive tests (CATs) were administered to assess fatigue, pain interference, physical function, depression, and anxiety. Checklists identified psychosocial concerns, informational and nutritional needs, and risk factors for inadequate nutrition. Assessment results, including PROMIS T-scores with documented severity thresholds, were immediately populated in the EHR. Clinicians were notified of clinically elevated symptoms through EHR messages. EHR integration was designed to provide automated triage to social work providers for psychosocial concerns, health educators for information, and dietitians for nutrition-related concerns.

Results

Of 4,042 MyChart messages sent, 3,203 (79%) were reviewed by patients. The assessment was started by 1,493 (37%) patients, and once started 93% completed (1,386 patients). Using first assessments only, 49.8% of patients who reviewed the MyChart message completed the assessment. Mean PROMIS CAT T-scores indicated a lower level of physical function and elevated anxiety compared to the general population. Fatigue, pain, and depression scores were comparable to the general population. Impaired physical functioning was the most common basis for clinical alerts, occurring in 4% of patients.

Conclusions

We used PROMIS CATs to measure common cancer symptoms in routine oncology outpatient care. Immediate EHR integration facilitated the use of symptom reporting as the basis for referral to psychosocial and supportive care.

Cancer patients commonly experience disease and treatment-related chronic and debilitating symptoms.1, 2 Many of the most prevalent symptoms, such as fatigue and pain, are best evaluated through direct patient report. Routine symptom assessment is recognized as an essential component of quality cancer care3 and is increasingly required for accreditation.4 Among patients receiving active treatment, symptom information is critically important to treatment decision-making.5 Evidence of improvement in disease-related symptoms can signify response to treatment due to reduced tumor burden. Treatment-related symptoms may be predictive of greater benefit from treatment.6 However, increased symptom burden can indicate disease progression. Furthermore, symptom burden due to treatment toxicities often helps guide decision-making with regard to dose reductions or delays.

Despite their clinical significance, many symptoms go unrecognized and untreated.7 It has been well documented that clinician symptom severity ratings are lower than patient report.8, 9 The discrepancy between clinician and patient ratings is greatest for more subjective symptoms, such as fatigue or distress.10 Complicated patient-provider communication dynamics contribute to discrepancies in symptom reporting. Clinicians may assume patients will initiate conversations regarding troublesome symptoms. This is of concern as patients often rely on their physicians to inquire about symptoms and may face disincentives to reporting symptoms,11 including fear of treatment changes or jeopardizing rapport. These patient-provider dynamics can lead to sub-optimal symptom management and therefore, missed opportunities to reduce the burden of cancer and improve quality of life for cancer survivors.

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) measures are considered to be the gold standard for quantifying the patient’s experience of a particular symptom or subjective concern.10, 12 Advances in health informatics have led to the development of systems for the electronic administration and scoring of PROs (ePROs). Several examples have been developed and implemented at academic and community-based cancer centers.13,14, 15 A comprehensive review of electronic patient-reported symptom assessment systems in oncology has been recently published.16

These systems have been demonstrated to be feasible, efficient, and to provide valuable information to patients and providers.17 However, many use single items to assess symptoms and may lack robust psychometric properties needed to detect small but meaningful symptom fluctuations over time. Alternatively, the trade-off is to administer lengthier assessments to obtain greater psychometric precision, though this is not feasible for most clinical settings. The meaningful use of PROs in the delivery of cancer care requires a system that provides precise, accurate, and robust symptom assessment that is brief and maximizes feasibility for clinical use. Ideally, this system should integrate PRO administration with the electronic health record (EHR). EHR integration offers many potential but as-yet untested advantages. EHR integration allows the coordination of PRO administration with meaningful clinic events, such as scheduled medical visits, to maximize clinical utility. Optimally-designed EHR integrated systems can provide the real-time delivery of PRO results and can enhance clinical operations through alerting clinicians to clinically significant symptoms. Automated triage to specialty providers when appropriate (eg. psychosocial care providers) through the EHR enhances coordination of care and can support sites in meeting emerging accreditation standards.4

NIH-supported advances in measurement science through the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) network (www.nihpromis.org)18, 19 provide an unprecedented opportunity to rapidly and precisely assess cancer-related symptoms using the most psychometrically robust tools available. PROMIS is a National Institutes of Health Common Fund (formerly Roadmap) Initiative to measure patient-reported symptoms and health-related quality of life across various conditions and disease populations. PROMIS computer adaptive tests (CATs) merge computer technology with measurement science and by doing so, rapidly assess target symptoms with as few as 4 items per symptom.20 We implemented the use of NIH PROMIS CATs to assess cancer-related symptoms with EHR integration to communicate assessment results to the clinical team in real-time. In this paper, we describe our model for implementing PROMIS ePROs into routine cancer care.

Methods

We created an ePRO assessment that included PROMIS CATs and checklists to assess psychosocial and nutritional concerns. We used Assessment Center™,21 a web-based platform for the administration of PROMIS CATs to create our assessment. PROMIS CAT development and validation, and Assessment Center™ have been previously described.20–23 Through custom programming we integrated assessment administration, scoring, and clinician notification with Epic, the EHR system used at our institution. We summarized assessment metrics as part of a clinical quality improvement initiative. The analysis of assessment metrics was part of a performance improvement project and thus was exempt from Institutional Review Board (IRB) Review, according to IRB guidance.24

Patients

Women with scheduled physician visits at the Lurie Cancer Center Gynecologic Oncology outpatient clinic were asked to participate. Patients were required to have an EHR patient communication portal account (Epic “MyChart”). A total of 636 women completed 1,493 assessments from November 2011 – February 2014. Patient demographic and medical characteristics were extracted from the EHR. The average age of the patients was 55.1 years (SD=12.8; range 21–90 years). The majority (78%) were non-Hispanic white (5% African American, 4% Asian, 4% Hispanic), which is comparable to the clinical population treated at the Lurie Cancer Center. The majority of patients had ovarian (35%), uterine (28%), or cervical (7%) malignancies (Table 1). A few (9%) had a non-gynecologic malignancy entered as the primary diagnosis for the clinical encounter (e.g., breast cancer).

Table 1.

Demographic and medical characteristics (N = 636)

| Patient Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Race | Total | % |

| White | 494 | 77.7 |

| Black | 33 | 5.2 |

| Asian | 26 | 4.1 |

| Other | 23 | 3.6 |

| Patient declined, per medical record | 41 | 6.4 |

| Unknown, per medical record | 17 | 2.7 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.3 |

| Ethnicity | Total | % |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 547 | 86.1 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 25 | 3.9 |

| Patient declined, per medical record | 62 | 9.7 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.3 |

| Cancer Type | ||

| Ovarian | 225 | 35.4 |

| Uterine | 179 | 28.1 |

| Cervical | 44 | 6.9 |

| Other female genital malignancy | 28 | 4.4 |

| Other malignancy coded for clinical encounter | 55 | 8.6 |

| Missing | 105 | 16.5 |

Measures

PROMIS CATs utilize a computer algorithm developed using item response theory (IRT) to administer PRO items selected from an item bank that are tailored to the patient’s symptom severity. An item bank is comprised of items calibrated by IRT-driven analysis to establish target symptom item banks.22, 25,26 Precise, reliable and valid symptom scores are generated with typically 4 items per symptom-specific item pool. Items are computer scored and benchmarked based on normative data from cancer patients and the general population. PROMIS CATs can be administered through Assessment Center™.21 PROMIS T-score clinical severity thresholds were previously determined using a standard setting exercise that converged clinician expert ratings and patient self-reported severity scores.27

The Gynecologic Oncology assessment consisted of PROMIS CATs that measured pain interference, fatigue, physical function, depression and anxiety. The assessment included items assessing psychosocial and nutritional concerns for triage to supportive oncology services. The psychosocial assessment was adapted from the NCCN-Distress Thermometer and Problem Checklist28 and consisted of a checklist of emotional, practical and informational concerns developed collaboratively with our social workers and health educator (e.g. coping with cancer diagnosis, communicating with medical team, financial resources). Nutritional assessment included new items and items adapted items from the Patient Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA)29 that assessed significant weight loss within the last two weeks, concerns about weight loss or weight gain, and a checklist of symptoms that interfere with maintaining nutrition, developed collaboratively with cancer center dietitians. Total assessment length for the PROMIS CATs, psychosocial and nutrition assessment was approximately 40 items, requiring an average of slightly less than 10 minutes to complete.

Procedures

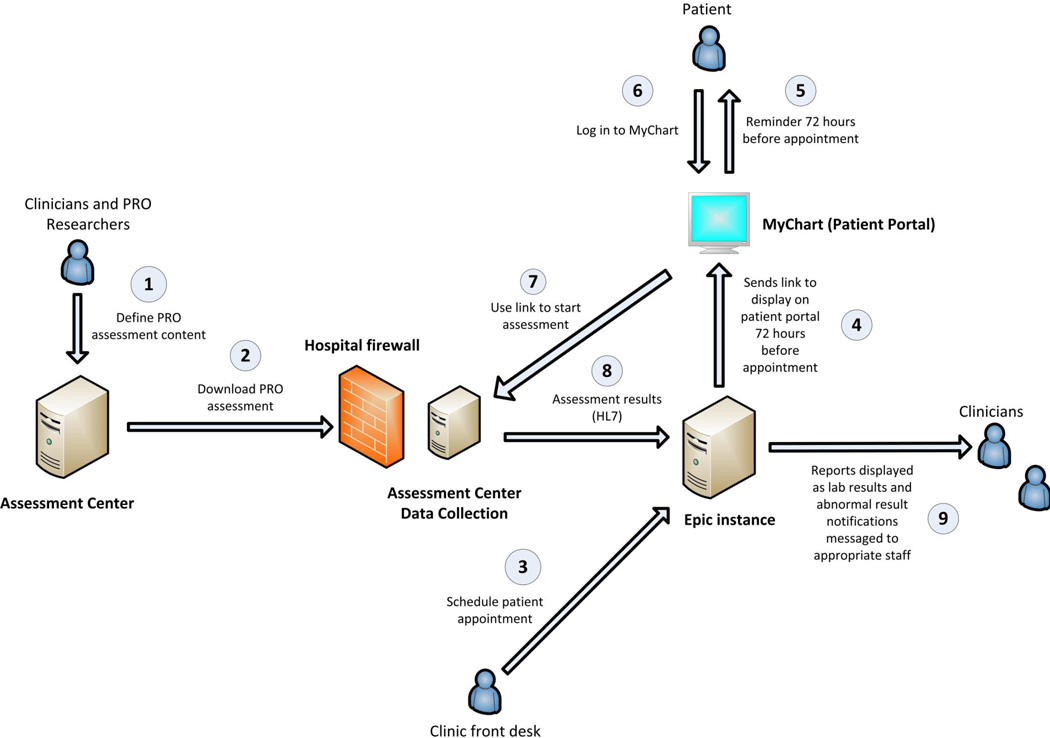

We implemented this ePRO assessment in our Gynecologic Oncology outpatient clinics. Figure 1 illustrates the electronic health record integration process. We created the assessment in Assessment Center™ and downloaded it within the hospital firewall for EHR integration. Patients with an Epic MyChart account received an email message 72 hours prior to scheduled physician visits alerting them to a new MyChart message. The MyChart message instructed patients to complete the ePRO assessment prior to their upcoming medical visit and provided a hyperlink that connected patients to the ePRO assessment in Assessment Center™. Clinic staff generated a daily list of patients who had scheduled medical appointments and had not completed the ePRO assessment. When these patients checked-in, clinic staff provided an iPad for patients to access their MyChart account and complete the assessment.

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating electronic medical record integration of PROMIS assessment

Assessment results were immediately documented in the EHR in three ways. First, all assessment results, including the date completed, PROMIS T-scores, severity interpretation (normal, mild, moderate, or severe), items administered, and patient responses were documented in the EHR in a designated section. Second, providers could copy assessment results into the typed progress note in the EHR. Third, clinicians were alerted to severe symptoms and patient concerns through messages sent to the messaging area (“in basket”) of the EHR.

Processes for clinician notification within the EHR messing system were developed in collaboration with gynecologic oncology and supportive oncology clinical providers. PROMIS T-scores in the severe range27 (T≥70 or ≥75, depending upon symptom) triggered electronic provider notification through EHR messages to the primary oncologist and a nurse message pool. The nurse message pool is an EHR in-basket with multiple recipients; for our purposes the nurse pool included gynecologic oncology nurses. Table 2 details the clinical messaging algorithms for each domain assessed. Medical and psychosocial providers followed-up with patients during clinic visits, by telephone, or through a MyChart message to the patient. Patients were asked for their preferred method of follow-up (MyChart message or telephone call) within the ePRO assessment. Standard clinical procedures were followed to manage patients who reported severe symptoms. Therefore by design the assessment did not ask patients to consent to follow-up contact by an oncology provider as consent was provided by virtue of signed patient consent to treatment.

Table 2.

ePRO assessment domains and clinician notification algorithms

| Symptom/Concern | Notification algorithm |

|---|---|

| Pain, Fatigue, Physical Function | Treating oncologist and nurse pool messaged when symptoms severe |

| Depression, Anxiety |

|

| Psychosocial concerns | Social work pool messaged with list of items endorsed by patient |

| Informational needs |

|

| Nutrition status | Dietitian messaged if weight loss thresholds met, key symptoms endorsed or patient requests consult |

Results

From November 2011 to February 2014, 636 patients completed a total of 1,493 assessments, with 636 patients completing the assessment at least once. Most patients (90.1%) completed the assessment at home, versus in-clinic (9.3%). The majority of patients asked to be contacted through MyChart (84%) versus by telephone (16%) for any follow-up.

Health record integration

We demonstrated our ability to integrate the administration and scoring of an ePRO assessment within the EHR (Figure 1). Through integration, a clinical event (e.g. scheduled medical visit) triggered ePRO assessment administration to patients and assessment results were immediately documented. Quality assurance testing was conducted by EHR and Assessment Center™ programmers to identify and resolve problems. To our knowledge, between November 2011 and February 2014, three minor problems occurred following EHR upgrades and required updated programming.

Feasibility

Patients (N = 636) with recurring scheduled medical visits completed the assessment multiple times (301 twice, 184 three times, 129 four times). We examined assessment completion rates for all assessment requests, noting that many patients completed the assessment multiple times. As shown in Table 3, 4,042 assessment requests through MyChart messages were sent across multiple time points. Of these, 3,203 messages (79%) were reviewed, 1,493 (37%) assessments were started and once started, 1,386 (93%) assessments were completed. We examined these same metrics based on the first assessment request only (first MyChart message), to evaluate acceptance and feasibility counting each patient only once. A total of 1,089 first assessment requests were sent. Of those, 874 (80%) messages were read and 435 assessments (40%) were started. Using only responses to the first MyChart message, 401 assessments were completed out of 1,089 MyChart messages that were generated (37% completion rate). We also evaluated feasibility by limiting these metrics to patients who read the MyChart message (n=874; 80% of messages generated), assuming patients who did not read the MyChart message may not maintain their account. Of patients who read the MyChart message (n=874), 435 patients (49.8%) provided assessment data. An additional 201 patients began the assessment after multiple MyChart message requests. Detailed results are now presented based on first assessments only (n = 636). Of these, five patients opened the assessment web-site but did not answer any items.

Table 3.

Assessment completion rates

| # MyChart messages sent |

# MyChart messages read |

Completion rate |

# assessments started |

Completion rate |

# assessments completed, once started |

Completion rate |

% completed from total eligible |

% patients who read MyChart message and provided assessment data |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total All Assessments | 4,042 | 3,201 | 79% | 1,493 | 37% | 1,396 | 93% | 34.5% | 46.7% |

| Total First Assessment only | 1,089 | 874 | 80% | 435 | 40% | 401 | 92% | 36.8% | 49.8% |

Symptom burden

In Table 4, PROMIS CAT symptom score descriptive statistics show 631 patients starting the assessment and 583 patients completing the assessment (92% assessment completion rate once patients begin). The physical functioning PROMIS CAT generated the most clinician notifications, indicating of the 5 domains assessed, impairment in physical functioning was the most common patient concern. The mean physical function T-score=46.6 (SD=9.6) indicated that patients reported lower physical function than the general population. The anxiety mean T-score=52.8 (SD=9.1) indicated a slightly elevated level of anxiety compared to the general population. Mean T-scores for fatigue, pain interference, and depression were comparable to the general population.

Table 4.

PROMIS CAT T-score descriptive statistics for First Assessment Only

| CAT Scores | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | Pain Interference |

Physical Function |

Anxiety | Depression | |

| N | 631 | 623 | 603 | 591 | 583 |

| Mean | 49.7 | 49.5 | 46.6 | 52.8 | 48.8 |

| Range | 24.3–77.7 | 38.6–80.1 | 20.0–73.3 | 32.9–84.9 | 34.2–77.4 |

| SD | 9.9 | 9.7 | 9.6 | 9.1 | 8.5 |

| Number of clinician notifications generated | 13 | 10 | 26 | 1 | 1 |

| Proportion generating notifications | 2.1% | 1.6% | 4.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% |

N based on number of completed PROMIS CATs

The proportion of patients with mild, moderate and severe PROMIS T-scores are presented in Table 5. Severe PROMIS symptom scores triggered a message to the oncology team (see Table 2). A total of 26 patients (4%) scored in the severe range on the physical function CAT. Provider notifications for fatigue (n=13, 2%) and pain (n=10, 2%) were infrequently generated. Severe anxiety or depression was rare (n=1; 0.2%). If we consider T-scores in the mild or moderate ranges to be clinically significant, 82% (n=492) of patients reported clinically significant impairments in physical functioning. About half of patients reported pain interference in the mild range or higher (n=317; 51%), fatigue severity above normal (n=295; 47%), and anxiety as mild or more severe (n=252; 43%). Approximately 22% reported depression scores in the mild range (n=131) and the majority (n=439; 75%) had depression scores in the normal range.

Table 5.

PROMIS CAT T-score proportion by symptom severity

| Normal | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Completed CAT (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue (T-score) | <50 | 50–59 | 60–69 | ≥70 | n=631 |

| # of patients | 336 | 193 | 89 | 13 | |

| % of patients | 53% | 31% | 14% | 2% | |

| Pain Interference (T-score) | <50 | 50–59 | 60–69 | ≥70 | n=623 |

| # of patients | 306 | 212 | 95 | 10 | |

| % of patients | 49% | 34% | 15% | 2% | |

| Physical Function (T-score) | >55 | 54-46 | 45-31 | ≤30 | n=603 |

| # of patients | 111 | 232 | 234 | 26 | |

| % of patients | 18% | 38% | 39% | 4% | |

| Anxiety (T-score) | <55 | 55–64 | 65–74 | ≥75 | n=591 |

| # of patients | 339 | 200 | 51 | 1 | |

| % of patients | 57% | 34% | 9% | <1% | |

| Depression (T-score) | <55 | 55–64 | 65–74 | ≥75 | n=583 |

| # of patients | 439 | 131 | 12 | 1 | |

| % of patients | 75% | 22% | 2% | <1% |

Psychosocial concerns

Among 617 patients who completed the psychosocial checklist, most (n=407; 66%) reported no psychosocial concerns. The most common psychosocial needs were information on advance directives (16%), support with managing stress (15%), information on financial resources (11%), coping with cancer diagnosis (10%), and information on support groups (9%). A total of 137 patients (25%) indicated that they would like to be contacted by a health educator for assistance finding health-related information.

Nutrition-related concerns

Among 541 patients who completed the nutrition checklist, a total of 178 patients (33%) endorsed at least one item that generated a message notification to dietitians. A small proportion (4%) of patients reported concern about recent weight loss. Most patients (72%) reported stable weight; an equal number reported weight loss (13%) or weight gain (15%) over the past two weeks. The most common reasons for EHR messaging to dietitians included interest in information to gain or lose weight (35%), feeling full quickly (14%), appetite loss (13%), constipation (12%), nausea (11%), taste changes (9%) and fatigue that interferes with maintaining adequate nutrition (9%).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first program to accomplish the clinical integration of PROMIS CAT administration, scoring and reporting within an EHR system. This preliminary work demonstrates a model for integrating PROMIS CAT administration for routine oncology care. In doing so, we have translated state-of-the-art advances in measurement science and health informatics to clinical application aimed at improving the delivery of cancer care. Our initial metrics support the feasibility of this approach. The integration of PROs as a component of quality cancer care, as well as the utilization of health information technology to enable real-time analysis of data from cancer patients (“learning health care system”) has been increasingly emphasized, most recently in an IOM report on quality cancer care.30 Several web-based and computer-based assessments have been developed for the assessment of symptoms13,14, 15 however, most approaches utilize single-item ratings for symptom assessment and may lack psychometric rigor or are too lengthy for repeat administration in busy clinical settings, limiting use for measuring outcomes. In using PROMIS CATs for symptom assessment, our program represents the most psychometrically robust approach by allowing precise measurement of symptoms while maintaining the brevity required for clinical implementation.

EHR integration may bypass common patient-provider communication barriers by collecting pre-visit ePROs and delivering results in real-time, at the point of care. ePRO scores automatically populate the EHR, with clinician notification of severe symptoms to ensure that clinically significant symptoms are addressed. EHR integration also facilitates automated triage for psychosocial and supportive care. Qualitative feedback from our gynecologic oncology providers is consistent with research demonstrating PROs improve clinical workflow in allowing providers to focus the medical visit on symptoms of concern and track symptom severity over time.31

We identified physical functioning impairments and anxiety as the most common concerns among gynecologic oncology outpatients. Pain and fatigue scores were comparable to the general population, with 16% of patients reporting moderate or severe fatigue and 17% reporting moderate or severe pain interference. Overall, one-third of patients reported current psychosocial health needs.

Psychosocial triage based on patient report of distress and related concerns improves the efficiency of our program, in allowing us to provide tailored psychosocial care for patients most in need of support. Emerging accreditation standards require that patients be screened for distress and referred for psychosocial care when needed32 though evidence documenting improved outcomes is just emerging.33 Therefore, now that we have implemented a program for assessment and triage an important next step is to evaluate outcomes.

With regard to feasibility, approximately 8 out of 10 patients read the initial MyChart message asking patients to complete the ePRO assessment, yet only one-third ultimately completed the entire assessment. This is lower than response rates from similar ePRO initiatives,15 however a key difference is that our program required patients to initiate the assessment whereas other programs administered ePRO assessment on-site. Our program is optional and newly integrated into the clinical workflow, therefore patients were not overtly encouraged to participate. Future efforts are required to implement strategies to encourage more widespread patient participation. Nine out of 10 patients who completed the assessment did so at home prior to medical visits. Based on anecdotal comments from patients and clinicians, the majority found it to be a positive experience. We anticipate that adherence will increase as the administration of ePROs prior to scheduled medical visits becomes a part of routine cancer care. The systematic evaluation of outcomes associated with this initiative, as well as clinician perspectives on the clinical utility of assessment results and notifications, are important next steps.

We note several limitations of data summarized in this report. Implementation of this ePRO assessment was conducted as a clinical initiative, therefore, data were extracted from the EHR and only available for the subgroup of patients who have an EHR patient electronic communication account and who accessed and completed the assessment. We were unable to estimate the percentage of patients who were excluded due to not having an account. It is possible patients completing the assessment may differ from those who did not. This limits generalizability to patients who are “wired” to their EHR. In this first report, we summarized metrics supporting the feasibility of this approach, however we did not report outcomes. Our next report will focus on the clinical team’s response to assessment results and resulting patient-centered outcomes.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the successful implementation of an ePRO system for the precise, valid, and robust measurement of common cancer-related symptoms, with immediate clinician notification and triage for problems identified. In doing so, we employed state-of-the-art measurement science to bring the patient’s voice to the clinical encounter with the ultimate goal of optimal symptom and psychosocial management for improved cancer care delivery.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: Coleman Foundation, William W. Wirtz Cancer Innovation Fund, #R01 CA60068 and U5 AR057951. The authors wish to acknowledge colleagues for their contributions to this project: Mary Jo Graden, Mary O’Connor, Virginia Nothnagel, Rebecca Caires, Karen Giammiccho, Vicki Diep, Darren Kaiser, Robert Milfajt.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest and Disclosure Statement: The authors have no disclosures to report

References

- 1.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. Symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress in a cancer population. Quality of Life Research. 1994;3:183–189. doi: 10.1007/BF00435383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cella D. Factors influencing quality of life in cancer patients: Anemia and fatigue. Seminars in oncology. 1998;25:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abernethy AP, Zafar SY, Wheeler JL, Lyerly HK, Ahmad A, Reese JB. Electronic patient-reported data capture as a foundation of rapid learning cancer care. Medical Care. 2010;48:S32–S38. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181db53a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Surgeons Commission on C. Cancer Program Standards 2012 : ensuring patient-centered care. Available from URL: http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/cocprogramstandards2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basch E, Abernethy AP. Supporting Clinical Practice Decisions With Real-Time Patient-Reported Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:954–956. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Cella D, Fallowfield L. Treatment-emergent endocrine symptoms and the risk of breast cancer recurrence: a retrospective analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008:1143–1147. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vogelzang NJ, Breitbart W, Cella D, et al. Patient, caregiver, and oncologist perceptions of cancer-related fatigue: Results of a tripart assessment survey. The Fatigue Coalition. Seminars in Hematology. 1997;34:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362:865–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fromme EK, Eilers KM, Mori M, Hsieh YC, Beer TM. How accurate is clinician reporting of chemotherapy adverse effects? A comparison with patient-reported symptoms from the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire C30. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:3485–3490. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basch E, Iasonos A, McDonough T, et al. Patient versus clinician symptom reporting using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: results of a questionnaire-based study. Lancet Oncology. 2006;7:903–909. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70910-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dupont A, Wheeler J, Herndon IJE, et al. Use of tablet personal computers for sensitive patient-reported information. Journal of Supportive Oncology. 2009;7:91–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snyder CF, Aaronson NK. Use of patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice. Lancet. 2009;374:369–370. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abernethy AP, Herndon JE, Wheeler JL, et al. Feasibility and Acceptability to Patients of a Longitudinal System for Evaluating Cancer-Related Symptoms and Quality of Life: Pilot Study of an e/Tablet Data-Collection System in Academic Oncology. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2009;37:1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark K, Bardwell WA, Arsenault T, DeTeresa R, Loscalzo M. Implementing touch-screen technology to enhance recognition of distress. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18:822–830. doi: 10.1002/pon.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlson LE, Groff SL, Bultz BD, Waller A, Zhong L. Online screening for distress, the 6th vital sign, in newly diagnosed oncology outpatients: Randomised controlled trial of computerised vs personalised triage. British Journal of Cancer. 2012;107:617–625. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett AV, Basch E, Jensen RE. Electronic patient-reported outcome systems in oncology clinical practice. CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2012;62:336–347. doi: 10.3322/caac.21150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berry DL, Blumenstein BA, Halpenny B, et al. Enhancing Patient-Provider Communication With the Electronic Self-Report Assessment for Cancer: A Randomized Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:1029–1035. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2010;63:1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, Cella D. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS):depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18:263–283. doi: 10.1177/1073191111411667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi SW, Reise SP, Pilkonis PA, Hays RD, Cella D. Efficiency of static and computer adaptive short forms compared to full length measures of depressive symptoms. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19:125–136. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9560-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gershon R, Rothrock NE, Hanrahan RT, Jansky LJ, Harniss M, Riley W. The development of a clinical outcomes survey research application: Assessment CenterSM. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19:677–685. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9634-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cella D, Gershon R, Lai JS, Choi S. The future of outcomes measurement: item banking, tailored short-forms, and computerized adaptive assessment. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16:133–141. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2010;63:1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Office of Human Research Protections. Quality Improvement Activities - Frequently Asked Questions. [accessed June 23, 2014]; Available from URL: http://answers.hhs.gov/ohrp/questions/7282.

- 25.Lai JS, Cella D, Choi SW, et al. How Item Banks and Their Application Can Influence Measurement Practice in Rehabilitation Medicine: A PROMIS Fatigue Item Bank Example. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2011;92:S20–S27. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai JS, Cella D, Dineen K, Von Roenn J, Gershon R. An item bank was created to improve the measurement of cancer-related fatigue. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2005;58:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cella D, Choi S, Rosenbloom SK, et al. A novel IRT-based case-ranking approach to derive expert standards for symptom severity. Quality of Life Research. 2008 ISOQOL Conference Supplement. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, et al. Distress management. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2010;8:448–485. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauer J, Capra S, Ferguson M. Use of the scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) as a nutrition assessment tool in patients with cancer. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;56:779–785. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levit LA, Balogh E, Nass SJ, Ganz P. Institute of Medicine Committee on Improving the Quality of Cancer Care Addressing the Challenges of an Aging Population. Delivering high-quality cancer care : charting a new course for a system in crisis. 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snyder CF, Jensen RE, Geller G, Carducci MA, Wu AW. Relevant content for a patient-reported outcomes questionnaire for use in oncology clinical practice: Putting doctors and patients on the same page. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19:1045–1055. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9655-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobsen PB, Wagner LI. A new quality standard: The integration of psychosocial care into routine cancer care. J. Clin. Oncol. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:1154–1159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carlson LE, Groff SL, Maciejewski O, Bultz BD. Screening for Distress in Lung and Breast Cancer Outpatients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:4884–4891. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]