Abstract

In our previous findings, we have demonstrated that aspirin/acetyl salicylic acid (ASA) might induce sirtuins via aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ah receptor). Induction effects included an increase in cellular paraoxonase 1 (PON1) activity and apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1) gene expression. As predicted, ASA and salicylic acid (SA) treatment resulted in generation of H2O2, which is known to be an inducer of mitochondrial gene Sirt4 and other downstream target genes of Sirt1.

Our current mass spectroscopic studies further confirm the metabolism of the drugs ASA and SA. Our studies show that HepG2 cells readily converted ASA to SA, which was then metabolized to 2,3-DHBA. HepG2 cells transfected with aryl hydrocarbon receptor siRNA upon treatment with SA showed the absence of a DHBA peak as measured by LC-MS/MS. MS studies for Sirt1 action also showed a peak at 180.9 m/z for the deacetylated and chlorinated product formed from N-acetyl Lε-lysine. Thus an increase in Sirt4, Nrf2, Tfam, UCP1, eNOS, HO1 and STAT3 genes could profoundly affect mitochondrial function, cholesterol homeostasis, and fatty acid oxidation, suggesting that ASA could be beneficial beyond simply its ability to inhibit cyclooxygenase.

Keywords: ASA, fatty acid oxidation, H2O2, mitochondrial transcription factor A

1. Introduction

Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) has an analgesic property and serves as an important modulator of cyclooxygenase (COX), and thus the production of thromboxanes (Vane, 1971; Vane and Botting, 2003; Rowlinson, 2003). The beneficial actions of ASA have been mainly attributed to this property; ASA is believed to be readily hydrolyzed by enzymes, including paraoxonase 1 (PON1) (Santanam and Parthasarathy, 2006) to salicylic acid (SA). ASA has a short plasma half-life of less than 15 min and the product, SA, has profound biological actions of its own. The half-life of SA exceeds several hours and is concentration-dependent. In addition to its well-known analgesic actions (Williams and Hennekens, 2004; Hennekens et al., 1989; Claria and Serhan, 1995), SA also has been extensively studied as a hydroxyl radical trap (John et al., 1993). It is excreted as a glucuronide and other conjugates (Gutierrez et al., 2006), suggesting that it undergoes metabolic conversion in the liver. However, SA is known to be metabolized by liver microsomes enzymatically as well as non-enzymatically (Grootveld and Halliwell, 1986) to 2,3- and 2,5- dihydroxy benzoic acid (DHBA) by hydroxyl radicals. These dihydroxybenzene derivatives, such as 2,3- or 2,5-DHBA, are expected to autooxidize to form quinones and reactive oxygen species, particularly hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Kamble et al., 2013). Reactive oxygen species and H2O2 have been known to be attributed to an increase in the induction of sirtuins (Sirt) such as Sirt1, Sirt3 and Sirt4 (Alcendor, et al., 2004, Kwon and Ott, 2008). Recent studies showed that there are few protein substrates for Sirt 2–7 which play an important role in multiple disease-relevant pathways largely encompassing mitochondrial energetics and inflammatory cardiomyopathy. Increased Sirt1 activity would decrease glucose levels, increase the number of mitochondria, regulate insulin sensitivity and lower body weight (Elliott and Jirousek, 2008). Among other sirtuins, Sirt4 is a mitochondrial protein that does not display Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-dependent deacetylase activity, but it utilizes NAD for carrying out adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-ribosylation of glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) in the mitochondria. Nevertheless, ADP-ribosylation of GDH represses GDH activity by Sirt4, which limits metabolism of glutamate and glutamine to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (Haigi et al., 2006). Thus, we tested the ability of ASA and SA to generate H2O2 to induce Sirt4, Nrf2, Tfam, UCP1, eNOS and STAT3 genes responsible for mitochondrial function and liver × receptorα, farnesoid × receptor and PPARα genes involved in lipogenesis and cholesterol homeostasis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemicals

ASA and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO). HepG2 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), (Manassas, VA). All other reagents used were of analytical grade. PCR primers and cell culture reagents were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

2.2 Cell Culture and treatment by ASA

HepG2 cells were cultured in advanced DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and were maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

2.3 Incubation of HepG2 cells

HepG2 cells were pretreated with phenol red-free and serum free MEM for 4h. Cells were incubated with either 50 µM or 0.1 mM ASA for 48 h in the same medium. ASA was dissolved in absolute alcohol. A control was maintained with alcohol alone. At the end of the treatment, the medium was removed and the cells were washed with PBS and harvested in Trizol® (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for RNA isolation.

2.4 Sirt4, Tfam, UCP1, STAT3, Lliver X Receptorα, Farnesoid X Receptor, PPARα, HO1 and eNOS gene expression

Total RNA was extracted from cells after ASA treatment by using Trizol® (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. First strand cDNA synthesis was performed from 1 μg total RNA. Reverse transcriptase products were subjected to PCR amplification with Ready Mix PCR Master Mix (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Oligonucleotide primers were designed on the basis of the cDNA sequences reported in the Gene Bank database. Primers were designed by using Invitrogen Oligo Perfect® and represented in Table 1. RT-PCR was performed for the analysis of gene expression.

Table 1.

List of oligonucleotide primers used for RT-PCR

| Species | Target | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Sirt 4 | 5'-TCCCCAGACACCCTGTTTTA-3' | 5'-GCAATTTCCCAAGTCTCTG-3' |

| Nrf2 | 5'-ACACACAGGTGGGACACAAA-3' | 5'-CTGGGGTGGTCTCGATTTTA-3' | |

| Tfam | 5'-GGGTTCCAGTTGTGATTGCT-3' | 5'-TGGACAACTTGCCAAGACAG-3' | |

| UCP1 | 5'-TCTCTCAGGATCGGCCTCTA-3' | 5'-GCCCAATGAATACTGCGACT-3' | |

| STAT3 | 5'-GGTATCTGGGGAACCATGTG-3' | 5'-CTTTCCCTACCCCCATCATT-3' | |

| Liver × receptorα | 5'-TCGCAAGTGCCAGGAGTGTC-3' | 5'-CGCCGGTTACACTGTTGCTG-3' | |

| Farnesoid × receptor | 5'-GGACAGAACCTGGAAGTGGA-3' | 5'-AGCTCATCCCCTTTGATCCT-3' | |

| PPARα | 5'-CAGGCACAGCACAGTCGCTCAT-3' | 5'-CCCGAGTAGCTGGGATTAC-3' | |

| HO1 | 5'-CTTCTTCACCTTCCCCAACA-3' | 5'-GCTCCTGCAACTCCTCAAAG-3' | |

| eNOS | 5'-ACCCTCACCGCTACAACATC-3' | 5'-GCTCATTCTCCAGGTGCTTC-3' | |

| GAPDH | 5'-ACCCAGAAGACTGTGGATGG-3' | 5'-CACATTGGGGGTAGGAACAC-3' |

2.5 LC-MS/MS analysis for detection of ASA/SA and its metabolites

HepG2 cells were treated either with 25 µM ASA or SA and incubated for a period of 2h on a rocker. ASA/SA was dissolved in methanol and reactions were maintained in HBSS. At the end of treatment, the medium was collected and pH was adjusted to 6.00. HepG2 cells were washed gently with PBS. Cells were lysed in HBSS by sonication and centrifugation. The supernatant was collected and metabolites in the buffer were extracted by ether. Samples were subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis. ASA and SA were used as quantitative standards for the experiments.

High-performance liquid chromatography was run on a Shimadzu (Columbia, MD) system as described previously (Litvinov et al., 2010). Briefly, 3200 Q TRAP LC-MS/MS (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, MA) was used for the analysis. Samples were injected using a Hamilton syringe of 4.6 μm in diameter with a set flow rate of 10.00 μl/min. Negative ion electrospray ionization (-ESI) mode was employed, and a Q1MS Q1 scan was conducted to simultaneously scan for ions between 100–300 m/z. Heat block temperature for the analysis was set at 350°C, with ion source gas 1 flow set at 20 μl/min and detector voltage at 5500 eV. The MRM transitions of 187.2 amu to 125.2 amu and 202.3 amu to 140.3 amu were monitored for the detection of ASA and SA respectively.

2.6 LC-MS/MS analysis for HepG2 cells transfected with small interfering RNAs (siRNA) and treated with SA

For the Ah receptor silencing studies, HepG2 cells were grown in a 6-well plate and used for experiments. As described earlier, Ah receptor is an important receptor for SA and its further conversion to 2,3-DHBA via Cyp1A1. Therefore, by silencing Ah receptor using Ah receptor siRNA, SA metabolism can be tested for mediation by Ah receptor. siRNA experiments for Ah receptor were performed as described previously (Prescilla et al., 2008). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were washed with PBS and incubated with fresh medium. Transfected HepG2 cells were maintained in Hanks medium for 4 h, then incubated with SA at a concentration of 25 µM for 2 h on a rocker. The medium was collected and the pH was adjusted to 6.00, and the compound was extracted by ether. Cell lysate was prepared by sonication followed by centrifugation and supernatant fractions obtained were used for ether extraction. Samples were dissolved in methanol and analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

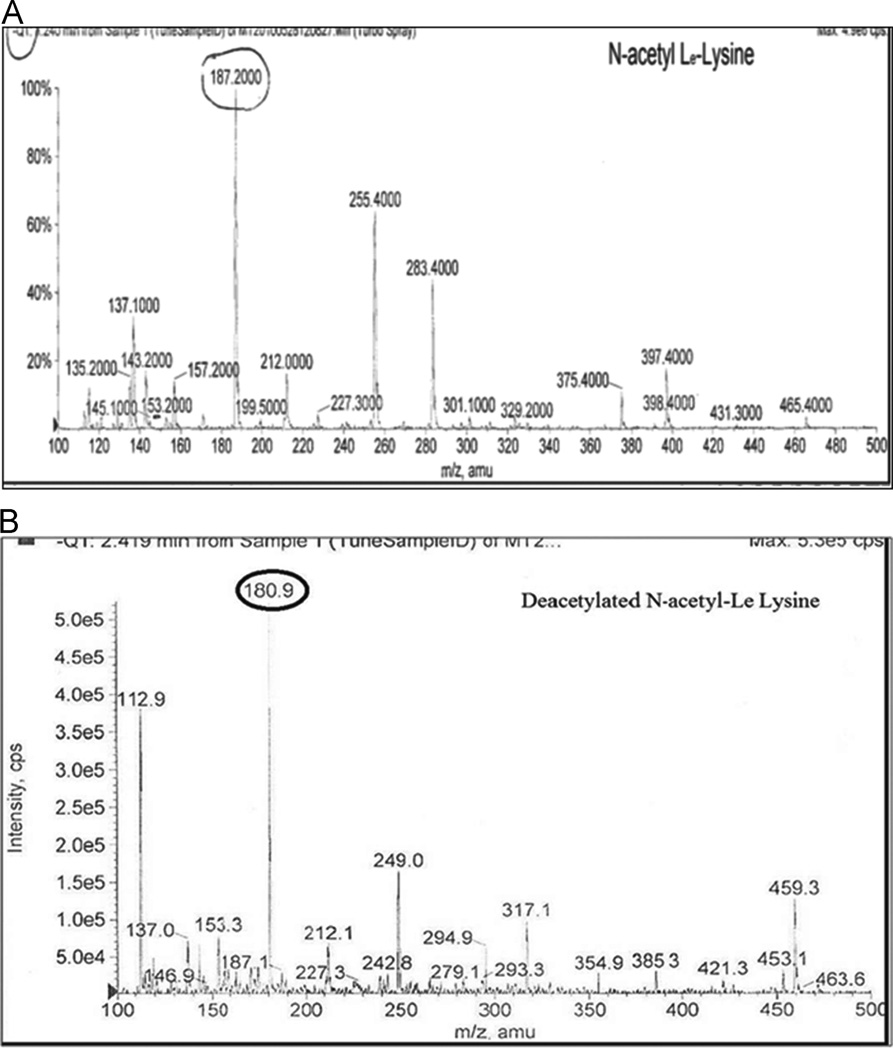

2.7 LC-MS/MS analysis for detection of Sirt1 deacetylation of N-acetyl-Lε-lysine

As Sirt1 belongs to the histone deacetylase (HDAC) family of proteins (Elliott and Jirousek, 2008), its deacetylation status is determined by using N-acetyl-Lε-lysine. High-throughout mass spectrometry used for Sirt1 studies detects the change in mass observed in N-acetyl-Lε-lysine as the substrate is deacetylated. Deacetylation results in a mass change from 188.20 atomic mass units (amu) in the substrate to 180.9 amu, representing a deacetylated, chlorinated form of the compound. The assay was performed using cell extract, NAD+, and N-acetyl-Lε-lysine, which were incubated at 25°C for 25 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 10% formic acid, and conversion of substrates to products was monitored by mass spectrometry. The ability of test compounds to activate the Sirt1 enzyme was monitored by comparing the change in m/z assigned peaks, which showed a conversion of substrate to product in various treated and untreated extracts (Ozbal et al., 2004).

2.8 Measurement of ATP levels

ATP levels were determined following the protocol by Liu et al. (2006). Adenosine triphosphates were extracted from cell supernatant fractions with 1 ml of 0.6 mMol/L perchloric acid in an ice bath for 1 min. The extraction mixture was centrifuged for 10 min at 3400 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant was quickly neutralized by adding 2 M KHCO3 and 0.1 M Tris followed by measurement of absorbance at 254 nm.

2.9 Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed at least 3 times with triplicate measurements. The data are expressed as mean ± S.D. and student’s t-test was applied for significance at P<0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1 ASA induces genes involved in the regulation of mitochondrial function Sirt4, Nrf2, Tfam, UCP1 and STAT3 gene expression in HepG2 cells

Sirt4 is a mitochondrial protein that utilizes NAD+ for carrying out ADP-ribosylation of glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) in mitochondria (Haigi et al., 2006). Treatment of HepG2 cells with 50 μM ASA for 48 h resulted in an increase in Sirt4 (4.55 ±1.8 fold) as compared to control (Fig. 1A). Nrf2 is a nuclear respiratory factor known for transcriptional control of mitochondrial genes. It is essential in mitochondrial biogenesis (Elliott and Jirousek, 2008; Repa and Mangelsdorf, 2000). Increased Nrf2 gene expression was observed at both 50 µM (2.863 ± 0.1 fold) and 0.1 mM (2.184 ± 0.01 fold) ASA treatment for 48 h as compared to control (Fig 1B). Similarly, increased Tfam expression (4.242 ± 0.05 fold) was observed in 50μM ASA treated samples as compared to the control (Fig. 1C). However, cells treated with 0.1 mM ASA did not show any change. Mitochondrial transcription factor A (Tfam) is essential for transcribing nuclear encoded mitochondrial proteins, such as structural proteins as well as proteins involved in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) transcription, translation, and repair (Hock and Kralli, 2009).

Fig 1. Genes involved in regulation of mitochondrial function.

HepG2 cells cultured in 6 well plates were treated with ASA (50 μM-0.1 mM ASA) for 48 h. As shown here, at 50 μM concentration Sirt4 (Fig 1A), Nrf2 (Fig 1B), Tfam (Fig 1C), UCP1 (Fig 1D) and STAT3 (Fig 1E) genes were increased compared to control. Values are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n=3). Statistically significant changes between untreated and treated sets are marked as *(P<0.05).

To gain further insight into mitochondrial functioning, we studied UCP1. UCP1 is one of the mitochondrial transporter proteins which creates proton leaks across the inner mitochondrial membrane, separating oxidative phosphorylation from ATP synthesis (Jatroch et al.,. 2010). UCP1 is the only protein responsible for mitochondrial uncoupling and regulation of metabolic efficiency in various tissues as compared to other uncoupling proteins (Fedorenko et al.,. 2012). HepG2 cells treated with 50 μM ASA showed an increase in UCP1 gene expression (2.188 ± 1.1 fold) as compared to control (Fig. 1D). STAT3 is responsible for activation of complex I and complex II in the electron transport chain in cellular homeostasis (Wegrzyn et al., 2009). To study cellular homeostasis and mitochondrial activity following ASA treatment of HepG2 cells, we measured STAT3 gene expression. A significant increase in STAT3 induction was observed at both 50 μM (4.154 ± 0.7 fold) and 0.1 mM ASA (5.787 ± 0.1 fold) as compared to control (Fig. 1E).

3.2 The role of ASA in induction of genes involved in lipogenesis and cholesterol homeostasis Liver × receptorα, farnesoid × receptor and PPARα gene expression in HepG2 cells

Liver × receptorα serves as a dominant receptor involved in the control of hepatic lipogenesis (Alcendor, et al., 2004) and farnesoid × receptor maintains bile acid and cholesterol homeostasis (Lavu et al., 2008). HepG2 cells treated with 50 µM ASA showed a significant increase in liver × receptorα (159.3 ± 42.1 fold) and farnesoid × receptor (26.41 ± 1.1 fold) gene expression compared to control (Fig 2A and 2B). PPARs are known to be involved in controlling fatty acid oxidation. PPARα is also known to play a role in mitochondrial biogenesis (Alcendor et al., 2004, Kwon and Ott, 2008). A significant dose-dependent increase in PPARα gene expression was observed at both the concentrations of 50 μM ASA (7.691 ± 2.8 fold) and 0.1 mM ASA (9.162 ± 2.8 fold) treatment as compared to control (Fig. 2C).

Fig 2. Genes involved in lipogenesis and cholesterol homeostasis.

HepG2 cells treated with ASA (50 μM) showed a significant increase in gene expression of liver × receptorα (LXR) (Fig 2A), farnesoid × receptor (FXR) (Fig 2B) and PPARα (Fig 2C) as compared to control. The fold induction values are reported as mean ± S.D. (n=3) and statistical significance is shown as *(P<0.05).

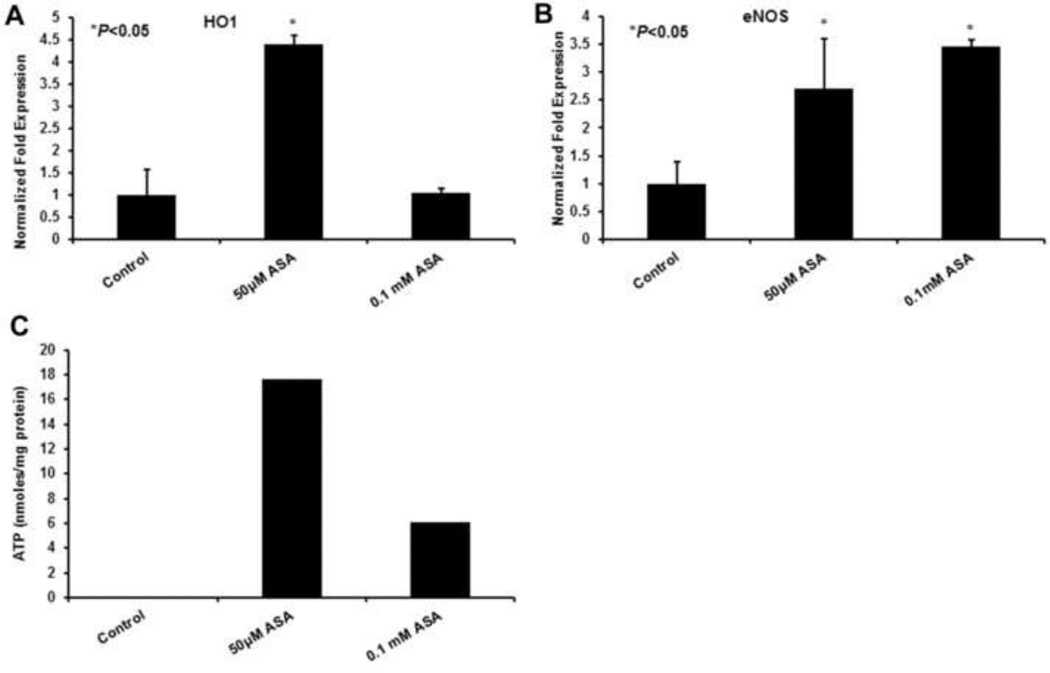

3.3 ASA induces HO1 and eNOS in HepG2 cells

Heme oxygenase 1 (HO1) has antioxidant effects by catalyzing the breakdown of heme to bilirubin (Slebos and Choi, 2003 and Clark et al., 2000). It is also induced under oxidative stress. ASA treatment caused a significant increase in gene induction of HO1 (4.399 ± 0.2 fold) as compared to control (Fig 3A). An increase in Sirt1 as reported in our previous studies (Kamble et al., 2012) suggests the deacetylating role of Sirt1 and the induction of eNOS gene could prevent oxidative apoptosis and cell senescence (Kwon and Ott, 2008). Figure 3B shows HepG2 cells treated with 50 µM (2.704 ± 0.9 fold) and 0.1 mM (3.459 ± 0.11 fold) ASA for 48 h increased eNOS gene expression as compared to the control.

Fig 3. ASA role in induction of HO1, eNOS and ATP levels in HepG2 cells.

A significant increase was observed in HO1 (Fig 3A) and eNOS (Fig 3B) gene expressions at 50 μM ASA treated HepG2 cells as compared to controls. As shown in C, dose-dependent increase in ATP levels were observed in ASA-treated cells. Values are represented as mean ± S.D. (n=3) with statistical significance shown as *(P<0.05).

3.4 ATP levels in HepG2 cells treated with ASA

Evidence suggests that ASA plays a major role in increasing ATP levels during myocardial infarction and increases PGC1α. Our studies showed an increase in ATP levels as 17.65 and 6.06 nmoles/mg of protein at 50 µM and 0.1 mM of ASA treatment, respectively, at 48 h compared to the controls (0.076 nmoles/mg protein) (Fig 3C).

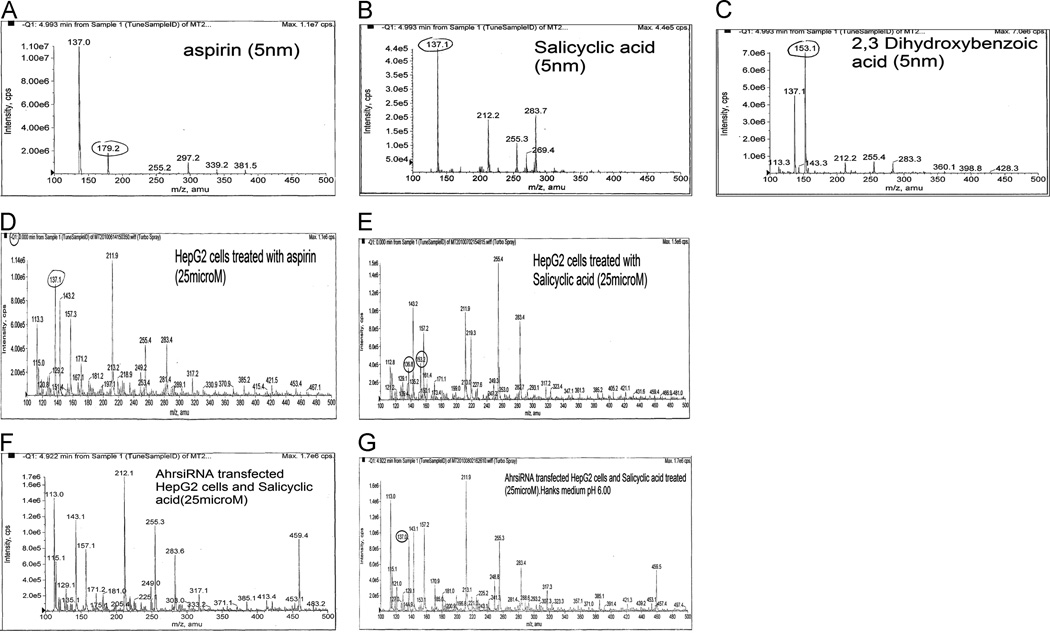

3.5 Identification of ASA metabolites in HepG2 cells treated with ASA and SA by mass spectrometry

As shown in Fig. 4 (A–C), standard peaks for ASA, SA and DHBA mass were determined using mass spectrometry. HepG2 cells treated with 25 μM ASA showed a peak at 137.1 amu (Fig. 4D) suggesting the ASA metabolite, SA, formed after cell-dependent enzymatic reactions. Similarly, HepG2 cells treated with SA showed peaks at 136.8amu and 153.2amu, suggesting some breakdown of SA. (Fig 4E).

Fig 4. LC-MS/MS studies for detection of ASA metabolites in both HepG2 cells and transfected HepG2 cells treated with ASA and SA.

Figures 4A, B and C represent standard peaks for ASA, SA and DHBA, respectively. Figure 4 D and E show m/z values for ASA, SA and DHBA used to detect the values obtained after HepG2 cell treatment with ASA and SA.

A complete absence of a peak is noticeable for DHBA shown in HepG2 cells transfected with Ah receptor siRNA (Fig 4F); however, the medium alone extracted with ether after compound separation did show m/z value for SA (Fig 4G).

3.6 Identification of ASA metabolite DHBA in Ah receptor siRNA transfected and SA-treated HepG2 cells

In order to study Ah receptor dependence, we transfected HepG2 cells with Ah receptor siRNA and treated with 25 µM SA for 2 h. In the absence of Ah receptor, cells did not show any peak for SA or for its metabolite DHBA (Fig 4F), whereas the medium after extraction showed a peak at 137.0 amu depicting intact SA (Fig.4G).

3.7 Identification of Sirt1 deacetylation activity in ASA-treated HepG2 cells

In order to study the deacetylation of N-acetyl-Lε-Lysine (NAC), HepG2 cells were treated with ASA in the presence of NAC. Standard NAC has a peak at 189amu, whereas HepG2 cells treated with ASA (Fig 5B) show a peak at 180.9amu, indicating the deacetylation activity of Sirt1.

Fig 5. LC-MS/MS studies for detection of Sirt1 in ASA-treated HepG2 cells for deacetylation of N-acetyl-Lε-Lysine.

Standard form, NAC (A) shows a peak at 189 amu. HepG2 cells treated with ASA (50μM) alone have shown Sirt1 increase and also its deacetylation of substrate. Treatment of HepG2 cells with N-acetyl-Lε-Lysine show m/z value at 180.9 amu (Fig 5B).

4. Discussion

In our previous studies, we have demonstrated the induction of Sirt1 and PGC1α by ASA with a suggested mechanism showing the generation of O2−. and H2O2 as the inducer (Kamble et al., 2012). We have also reported that ASA hydrolysis to SA by PON1 and further hydroxylation to 2,3-DHBA by Ah receptor occurs via Cyp1A1 inducing Sirt1 and other antioxidants. A conclusion from previous studies is that induction of these transcription factors would coordinate in regulation of various metabolic processes, including cholesterol homeostasis and mitochondrial biogenesis.

Moreover, generation of O2−. and H2O2 in latter reactions has also been revealed in our previous studies. These studies showed that ASA metabolism generates H2O2, playing a critical role in inducing the proteins.

HepG2 are the most widely used in vitro models in pharmacological and toxicological studies. Though primary human hepatocytes have been considered as the best model or gold standard for these studies, because of their high variability, short life span, and limited availability, we deemed the HepG2 cell line more appropriate for our studies. HepG2 cells are relatively easy to maintain in culture and also widely used for toxicity studies. Although some of the studies showed low activities of drug-metabolizing enzymes, such as CYP3A4, CYP2A6, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19, in comparison with primary human hepatocytes, the HepG2 cell line is still considered a valuable model for risk assessment of toxicants and toxins because of its capability to retain many integral liver functions (Dykens et al., 2008; Rudzok et al., 2010).

The results presented in this study clearly show increases in some of the mitochondrial respiratory proteins such as Tfam, UCP1, eNOS, STAT3 and PPARα, as well as proteins responsible for cholesterol homeostasis, liver × receptorα, farnesoid × receptor and antioxidants HO1 and Nrf2. This would result in an increase in fatty acid oxidation, cholesterol efflux, mitochondrial biogenesis, reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) and also provide antioxidant effects. Lavu et al., (2008) have also reported that the liver × receptorα gene could serve as a dominant receptor in control of hepatic lipogenesis.

Further studies on Sirt1 show that it modulates mitochondrial biogenesis and also could coordinate metabolic rate (Canto et al., 2008). An increase in Sirt1 activity in HepG2 cells by ASA treatment suggests that Sirt1 deacetylates the lysine residue, which is evidenced by deacetylation of N-acetyl-Lε-lysine by Sirt1 as a substrate molecule for detecting Sirt1 activity. Our current mass spectrometry studies further confirms ASA metabolism to its metabolites. HepG2 cells treated with ASA undergo hydrolysis and form the metabolite SA, upon which further hydroxylation forms 2,3-DHBA. The metabolic product of ASA-treated HepG2 cells after lysis and ether extraction is SA, shown in our MS studies having a peak at 137.1amu. The standard peak for ASA, SA and 2,3-DHBA are 179.2, 137.1 and 153amu, respectively. The formed products further generate H2O2 by spontaneous reaction, believed to induce Sirt1. Additionally, HepG2 cells treated with SA gave peaks at 136.8 and 153.2amu, suggesting the formation of the metabolite 2,3-DHBA.

As mentioned earlier, Ah receptor is an important receptor for SA and SA’s further conversion to 2,3-DHBA via Cyp1A1. Thus, by silencing Ah receptor using Ah receptor siRNA, SA metabolism can be tested for mediation by Ah receptor. For this, the Ah receptor siRNA transfected cells were treated with SA and tested for its metabolite DHBA in the cell lysate compared to that of the lysate of intact Ah receptor, SA treated cells. One would expect the increase in SA peak; surprisingly, however, neither the SA nor its metabolite DHBA showed peaks, which led us to focus on the medium, which does show an intact SA peak at 137.0amu. Thus, MS studies suggest a requirement of Ah receptor in ASA metabolic pathways.

AhR silencing could have prevented SA uptake by cells. Silencing of Ah receptor affects several drug transporting genes like MCT1 (proton linked monocarboxylate transporter), MRPs, and MDRs (multi drug resistant genes). There might be the possibility that SA may not transfer into the cell due to the lack of Ah receptor (mediator of aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase).

Importantly, one of the observations that led to the present studies was the finding that ASA and SA induced the expression of AhR (Jaichander et al.,. 2008). It is likely that the massive induction observed could have resulted in an increased transport of SA into the cells. Additionally, Ah receptor is a cytosolic transcription factor and activates many phase I (i.e., CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP1B1), and phase II (UGT1A1, UGT1A6, GSTA1) detoxification enzymes, as well as ABC transporters. According to Kurzwaski et al.,. (2012) studies, Ah receptor silencing resulted in 33–35% decrease in CYP1B1 and CYP1A1 expression as compared to control cells. Our experiments do not distinguish at this point whether poor entry of SA resulted in the lack of formation of DHBA or down regulation of CYPs are involved. The results suggest that Ah receptor siRNA transfected cells are not only unable to convert SA to DHBA but also hinder SA’s uptake which might be focused further. This also suggests that Ah receptor might be playing a major role in drug uptake, which may be confirmed in future studies.

Thus, it can also be said that moderate activation of Sirt1 can enhance mitochondrial biogenesis (Elliott and Jirousek, 2008). No studies have yet shown a link between Sirt1 activity and human disease. Increased Sirt1 signifies a direct role in mediating the processes that also increase ATP under the regulation of certain proteins (Kwon and Ott 2008; Lavu et al., 2008). Sirt1 increase by ASA and its products also reveals increased fatty acid oxidation. Our UV-Vis studies show increased ATP levels by ASA treatment as compared to control. Previous studies by others on cardiac cells reported that ASA treatment increases ATP levels during myocardial infarction compared to control (Seth et al., 1994). Our proposed mechanism also suggests that ASA treatment would reduce cardiac stress by increasing ATP levels.

In addition, Sirt1 and 4 consume NAD+ as a cofactor in order to bring about deacetylation and activation of transcription factors (Elliott and Jirousek, 2008). An increase in ATP levels by this mechanism also documents reduced NAD+ consumption required for moderate increase in Sirt1 and 4 inductions. Furthermore, Sirt4 increase also suggests that it would inhibit GDH activity (Haigis et al., 2006). Presently, ASA metabolized products also induce eNOS gene expression in HepG2 cells, which shows that Sirt1 induces eNOS by deacetylation. This could improve mitochondrial biogenesis, and prevent oxidative apoptosis and cell senescence. In addition, an increase in Tfam, STAT3, PPARα and UCP1 by this pathway would improve mitochondrial number and energy state during various processes. STAT3 is responsible for the activation of Complex I and II in the electron transport chain which might maintain cellular homeostasis (Wegrzyn et al., 2009). An increase in this gene further suggests that ASA therapy could provide a significant action in increasing the electron transport chain pathway by activating the complexes required for cell survival and mitochondrial respiration. ASA treatment also improves further antioxidant enzymatic action. In our previous studies, we reported Sirt1 and PGC1α activation might be a contributing factor for Nrf2 and HO1 induction in HepG2 cells. It might regulate processes associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome. It can also make numerous favorable alterations in lipid metabolism, which includes promotion of reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), elevation of plasma HDL cholesterol, and inhibition of cholesterol absorption which could antagonize inflammatory signaling molecules.

Besides ASA’s beneficial action in maintaining cholesterol levels, it also induces certain antioxidant programs such as Nrf2 and HO1. Previous reports state that HO1 may represent various therapeutic targets (Cudadrado and Rojo, 2008) which includes statins, rapamycin, nitric oxide (NO), and probucol. It can also be said that processes which generate NO demonstrate the ability of ASA to induce HO1. An increase in HO1 implies a catalytic breakdown of heme to bilirubin, CO and iron, where bilirubin promotes antioxidant activity and its generation could reduce cytotoxicity (Slebos et al., 2003; Clark et al., 2000).

Therefore, in our studies, increases in HO1 and Nrf2 genes serves as an essential antioxidant defense. Our signaling experiments documented in previous studies show upregulation in MAPkinase signaling pathway suggestive of P38 MAPk inducing Ah receptor, Sirt1 and redox signalling. Moreover, NFkB decrease would induce PON1 and the antioxidant role of Nrf2 and HO1.

Evidence so far has documented a protective role of low-dose ASA in the prevention of ischemia-reperfusion injury. This further implies that ASA treatment is effective in replenishing ATP levels to above normal levels (Seth et al., 1994). ASA provides therapeutic benefits in metabolic, mitochondrial and cardiovascular conditions.

Altogether it can be said that the proposed pathway of ASA metabolism, which shows an increase in gene expression and activity of Sirt1 and PGC-1α, could show its additional effects by increasing targets, such as PPARα, liver × receptorα, farnesoid × receptor, Nrf2, HO1 and mitochondrial genes Tfam, STAT3, UCP1, eNOS and Sirt4 expression. In addition to these effects, an increase in ATP levels in cells implies that the drug shows beneficial action in relation to maintaining energy metabolic pathway.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by NIH RO-1 (Grant No. 60015108) on “Novel mechanisms by which aspirin might protect against atherosclerosis.”

The authors thank Dr. Kathryn Young Burge for her assistance in preparation of manuscript.

Abbreviations

- Ah receptor

Aryl-hydrocarbon receptor

- amu

Atomic mass unit

- ASA

Acetyl salicylic acid

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- COX

Cyclooxygenase

- DHBA

Dihydroxy benzoic acid

- eNOS

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- GDH

Glutamate dehydrogenase

- HDAC

Histone deacetylases

- HDL

High density lipoprotein

- HO

Heme oxygenase

- NAD

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- Nrf2

Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2

- PGC1

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator

- PON1

Paraoxonase 1

- PPARα

Peroxisome proliferater-activated receptor α

- RCT

Reverse cholesterol transport

- SA

Salicylic acid

- siRNA

Small interfering RNA

- Sirt

Sirtuin

- STAT

Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- Tfam

Transcription factor A mitochondrial

- UCP

Uncoupling protein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alcendor RR, Kirshenbaum LA, Shin-ichiro I, Vatner SF, Sadoshima J. Silent information regulator 2α, a longevity factor and class III histone deacetylase, is an essential endogenous apoptosis inhibitor in cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 2004;95:971–980. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147557.75257.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canto C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, Noriega L, Milne JC, Elliott PJ, Puigserver P, Auwerx J. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458:1056–1060. doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claria J, Serhan CN. Aspirin triggers previously unrecognized bioactive eicosanoids by human endothelial cell-leukocyte interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. 1995;92:9475–9479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark E, Foresti RC, Green J, Motterlini R. Dynamics of haem oxygenase-1 expression and bilirubin production in cellular protection against oxidative stress. Biochem. J. 2000;348:615–619. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado A, Rojo AI. Heme oxygenase-1 as a therapeutic target in neurodegenerative diseases and brain infections. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008;14(5):429–442. doi: 10.2174/138161208783597407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens JA, Jamieson JD, Marroquin LD, Nadanaciva S, Xu JJ, Dunn MC, Smith AR, Will Y. In vitro assessment of mitochondrial dysfunction and cytotoxicity of nefazodone, trazodone, and buspirone. Toxicol Sci. 2008;103:335–345. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott PJ, Jirousek M. Sirtuins: Novel targets for metabolic disease. Curr. Opin. Invest. Drugs. 2008;9:371–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorenko A, Lishko PV, Kirichok Y. Mechanism of Fatty-Acid-Dependent UCP1 Uncoupling in Brown Fat Mitochondria Cell, 12. 2012;151(2):400–413. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez A, Ratliff EP, Andres AM, Huang X, McKeehan WL, Davis RA. Bile acids decrease hepatic paraoxonase 1 expression and plasma high-density lipoprotein levels via farnesoid × receptor-mediated signaling of FGFR4. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006;26:301–306. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000195793.73118.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grootveld M, Halliwell B. Aromatic hydroxylation as a potential measure of hydroxyl-radical formation Invivo. Identification of hydroxylated derivatives of salicylate in human body fluids. Biochem. J. 1986;237:499–504. doi: 10.1042/bj2370499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai Li, Haixia Li, Ziegler N, Cui R, Liu J. Recent Patents on PCSK9: A New Target for Treating Hypercholesterolemia. Recent. Patents. on DNA. Gene Seq. 2009;3:201–212. doi: 10.2174/187221509789318388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigis M, Mostoslavsky R, Haigis KM, Fahie K, Christodoulou DC, Murphy AJ, Valenzurle DM, Yancopoulos GD, Karow M, Blander L, Wolberger C, Prolla T, Weindruch R, Alt FW, Guarente L. Sirt4 inhibits glutamate dehydrogenase and opposes the effects of calorie restriction in pancreatic cells. Cell. 2006;126:941–954. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Sandercock P, Collins R, Peto R. Aspirin and other antiplatelet agents in the secondary and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 1989;80:749–756. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.4.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hock MB, Kralli A. Transcriptional control of mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Annual Review of Physiology. 2009;71:177–203. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaichander P, Selvarajan K, Garelnabi M, Parthasarathy S. Induction of paraoxonase 1 and apolipoprotein A1 gene expression by ASA. J.Lipid. Res. 2008;200:1–26. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800082-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastroch M, Divakaruni AS, Mookerjee S, Treberg JR, Brand MD. Mitochondrial proton and electron leaks. Essays Biochem. 2010;47:53–67. doi: 10.1042/bse0470053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John S, Andrus PK, Williams CM, VonVoigtlander PF, Cazers AR, Hall ED. The use of salicylate hydroxylation to detect hydroxyl radical generation in ischemic and traumatic brain injury. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 1993;20:147–162. doi: 10.1007/BF02815368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamble P, Selvarajan K, Aluganti Narasimhulu C, Nandave M, Parthasarathy S. Aspirin may promote mitochondrial biogenesis via the production of hydrogen peroxide and the induction of Sirtuin1/PGC-1a genes. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2013;699:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H, Ott M. The ups and downs of SIRT1. Trends.Biochem. Sci . 2008;33:517–525. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khali A, Berrougui H. Mechanism of action of resverastrol in lipid metabolism and atherosclerosis. Clin. Lipidol. 2009;4:527–531. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzawski M, Dziedziejko V, Post M, Wójcicki M, Urasiñska E, Miêtkiewski J, Droździk M. Expression of genes involved in xenobiotic metabolism and transport in end-stage liver disease: up-regulation of ABCC4 and CYP1B1. Pharmacological Reports. 2012;64:927–939. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(12)70888-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavu S, Boss O, Elliott PJ, Lambert P. Sirtuins novel therapeutic targets to treat age-associated diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug. Disc. 2008;7:841–853. doi: 10.1038/nrd2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvinov D, Selvarajan K, Garelnabi M, Brophy L, Parthasarathy S. Anti-Atherosclerotic actions of Azelaic acid, an end product of linoleic acid peroxidation, in mice. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209(2):449–454. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.09.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Jiang Y, Luo Y, Jiang W. A Simple and Rapid Determination of ATP, ADP and AMP concentrations in Pericarp Tissue of Litchi Fruit by High Performance Liquid Chromatography. Food. Technol. Biotechnol. 2006;44:531–534. [Google Scholar]

- Ozbal CC, LaMarr WA, Linton JR, Green DF, Katz A, Morrison TB, Colin JH, Brenan R. High Throughput Screening via Mass Spectrometry: A Case Study Using Acetylcholinesterase. Assay. and Drug. Devel. Technol. 2004;2:373–381. doi: 10.1089/adt.2004.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repa JJ, Mangelsdorf DJ. The role of orphan nuclear receptors in the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2000;16:459–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlinson SW, Kiefer JR, Prusakiewicz JJ, Pawlitz JL, Kozak KR, Kalgutkar AS, Stallings WC, Kurumbail RG, Marnett LJ. A novel mechanism of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition involving interactions with Ser-530 and Tyr-385. J. Biol.Chem. 2003;278:45763–45769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305481200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudzok S, Schlink U, Herbarth O, Bauer M. Measuring and modeling of binary mixture effects of pharmaceuticals and nickel on cell viability/cytotoxicity in the human hepatoma derived cell line HepG2. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;244:336–343. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santanam N, Parthasarathy S. Aspirin is a substrate for paraoxonase-like activity: Implications in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2006;191:272–275. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth SD, Maulik M, Manchanda SC, Maulik SK. Role of aspirin in modulating myocardial ischemic reperfusion injury. Agents. Actions. 1994;41:151–155. doi: 10.1007/BF02001909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slebos D, Ryter Choi A. Heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide in pulmonary medicine. Resp. Res. 2003;1465:9921–9924. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vane JR. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis as a mechanism of action for aspirin-like drugs. Nat. New. Biol. 1971;231:232–235. doi: 10.1038/newbio231232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vane JR, Botting RM. The mechanism of action of aspirin. Throm. Res. 2003;110:255–258. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00379-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A, Hennekens CH. The role of aspirin in cardiovascular diseases--forgotten benefits? Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2004;5:109–115. doi: 10.1517/14656566.5.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegrzy J, Potla R, Chwae YJ, Sepuri NB, Zhang Q, Koeck T, Derecka M, Szczepanek K, Szelag M, Gornicka A, Moh A, Moghaddas S, Chen Q, Bobbili S, Cichy J, Dulak J, Baker DP, Wolfman A, Stuehr D, Hassan MO, Fu XY, Avadhani N, Drake JI, Fawcett P, Lesnefsky EJ, Larner AC. Function of mitochondrial STAT3 in cellular respiration. Science. 2009;323:793–797. doi: 10.1126/science.1164551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]