Abstract

Background

Mobile and automated technologies are increasingly becoming integrated into mental healthcare and assessment. The purpose of this study was to determine how automated daily mood ratings are related to the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9), a standard measure in the screening and tracking of depression symptoms.

Results

There was a significant relationship between daily mood scores and one-week average mood scores and PHQ-9 scores controlling for linear change in depression scores. PHQ9 scores were not related to the average of two week mood ratings. This study also constructed models using variance, maximum, and minimum values of mood ratings in the preceding week and two-week periods as predictors of PHQ-9. None of these variables significantly predicted PHQ-9 scores when controlling for daily mood ratings and the corresponding averages for each period.

Limitations

This study only assessed patients who were in treatment for depression therefore do not account for the relationship between text message mood ratings for those who are not depressed. The sample was also predominantly Spanish speaking and low-income making generalizability to other populations uncertain.

Conclusions

Our results show that automatic text message based mood ratings can be a clinically useful proxy for the PHQ9. Importantly, this approach avoids the limitations of the PHQ9 administration, which include length and a higher requirement for literacy.

Keywords: PHQ9, depression, text messaging, mhealth, digital health, disparities

The Affordable Care Act and the Mental Health Parity Act have resulted in the need for primary care clinics to not only provide easy access to mental health and substance abuse services, but also to measure the quality of these services using symptom and functional outcomes (Bascha et al., 2013). Frequently, primary care clinics meet this requirement through self-report assessment tools administered before or during clinic visits. For depression, the most commonly administered assessment is the PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001) a 10-item scale that can take a few minutes to administer if the patient can read, and longer when there are literacy difficulties. Relying solely on an in clinic assessment, however, might result in delayed identification of worsening mood when appointments are missed. This limits the ability to provide timely interventions that might ultimately reduce overall costs to the health care system. The measure is also retrospective over the past two weeks, which can be inaccurate, especially given memory impairments among people with depression (Illsley et al., 1995).

As access to mental health services increases, it is likely that these services will be increasingly utilized by a more diverse population. This includes people from low-income and low educational backgrounds, and ethnic minority patients who access mental health services at lower rates than other populations (Alegria et al, 2008). In these contexts, challenges to implementation of assessments are further exacerbated (Miranda et al., 2003). For example, even though the PHQ9 has been translated into many languages, immigrants often have limited literacy (even in their native language) resulting in the need for additional assistance to complete assessments increasing the amount of clinician time required. Patients from low-income backgrounds also have higher rates of missed appointments which could result in less regular follow-up (Organista et al., 1994). Given these challenges as well as the prevailing disparities in depression treatment for Latinos and other ethnic minority groups (Miranda et al., 2004; Lagomasino, et al., 2005), it is important to develop improved methods of assessment that can then lead to appropriate intervention.

Mobile phone based text messaging provides the opportunity for regular longitudinal monitoring, while eschewing many of the aforementioned problems with clinic-based PHQ9 administration. Text messaging is widely available and relatively easy to use (Pew, 2014). Importantly, it can serve to enhance depression treatment (Aguilera & Muñoz, 2011). Text messaging can be used to monitor mood over time, simply and conveniently, utilizing simple ratings used in practice (e.g., “Please rate your mood from 1–9”). Though text messaging may be less familiar to older individuals, or those who may have difficulty reading small phone screens, it is more familiar and common than other mobile technologies (e.g., apps), and research shows that use is increasing (Pew 2014) and that people who do not text can learn and use it for health purposes (Aguilera & Berridge, 2014).

The purpose of our study was to determine whether information derived from SMS mood ratings could serve as a reliable proxy for in-clinic mood assessment. We compared daily mood monitoring via text messaging with the PHQ-9 completed in the clinic. If text messaging is successful in approximating the PHQ9, it can be used as simple and effective way to monitor symptom level over time. Specifically, we aimed to determine whether and how PHQ-9 scores map on to mean mood rating in the past two weeks as well as to the slope of mood ratings to determine direction of functioning, and to the variability of mood ratings, which can indicate swings in mood.

Method

Thirty three people received daily automated text messages (via www.healthysms.org) measuring their mood (What is your mood right now on a scale of 1–9?) and inquiring about thoughts and activities as part of their participation in group cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in a public sector clinic. During this time, they also received a PHQ-9 each week that they attended the therapy group. Average age of participants was 52.6 (SD=10.28), 91% were Spanish speakers and 94% were Latino/a. Average PHQ9 starting score at the initiation of text based mood ratings was 12.6 (SD=7.62) with patients going on to complete an average of 6.7 PHQ9s. The percentage of people who used text messaging prior to the study was 58%; the rest learned how to use text messaging for this study. The average response rate to the text messages was 51.2% with a range of 9%–98%. The average number of mood ratings was 75.9 (range = 4–257). This study was approved by the local IRB and all participants provided verbal informed consent.

Analysis Plan

In order to investigate whether text message mood scores during the week tend to covary with depressive symptoms as measured by weekly PHQ-9 assessments provided during therapy sessions we conducted a series of hierarchical linear models (HLM). We were interested whether text message mood ratings may be more predictive of PHQ-9 scores for certain periods than others, analysis compared the use of either single day, one-week average, or two-week average mood ratings. We selected one- and two-week periods as the PHQ-9 asks respondents to consider the previous two weeks, although it is unclear if respondents do so in their report.

Results

There was a significant relationship between daily mood scores and one-week average mood scores and PHQ-9 scores controlling for linear change in depression scores (see Table 1). Although, the relationship between the two-week average mood and PHQ-9 scores was non-significant, the parameter estimate was quite similar to that of the daily ratings and one-week averages. To further explore whether one-week or two-week scores provided additional predictive power over daily mood ratings we conducted a series of models adding the averages as predictors while controlling for daily ratings. In these models the one-week average remained a significant predictor (t(49) = −2.28, p = .03, β = −0.95) above and beyond the daily mood ratings (t(14) = −3.32, p = .005, β = −1.07). The two-week average did not add significant prediction of PHQ-9 scores over and beyond daily mood ratings (t(20) = 0.30, p = .98, β = 0.03). Thus, it appears that PHQ-9 scores appear to be tracking the most recent days’ mood ratings and the previous week mood ratings more than the previous two week mood ratings. We also constructed models using variance, maximum, and minimum values of mood ratings in the preceding week and two-week periods as predictors of PHQ-9. None of these variables significantly predicted PHQ-9 scores when controlling for daily mood ratings and the corresponding averages for each period. This suggests that PHQ-9 scores track better to the average of the week rather than highs or lows or variability over that period.

Table 1.

Daily, One-Week Average, and Two-Week Average Mood Scores Predicting PHQ-9

| t-ratio | df | p | β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | −2.69 | 39 | 0.01 | −0.92 |

| One-Week | −2.46 | 54 | 0.01 | −1.02 |

| Two-Week | −1.56 | 22 | 0.13 | −1.13 |

We also were interested in how the within-person variability might correspond to the PHQ-9 scores reported during the therapy sessions. To examine this, we computed correlations between daily mood ratings, weekly and two-week averages, and PHQ-9 scores, and compared these correlations to intraclass correlations which adjust for within-person patterns in responding. Although the overall correlations were quite similar (r = −.56, −.56, −.60, p < .001) for each time point (daily, one-week, and two-week respectively) these intraclass correlations showed larger differences (r = −.25, −.41, −.50 for daily, one-week, and two-week respectively). The largest discrepancy is present in the single day correlation, suggesting that more individual variability exists in terms of how people’s daily mood ratings correspond to PHQ-9 ratings than the average measures. This is reasonable given that one-week and two-week averages are t composite measures and thus have less error.

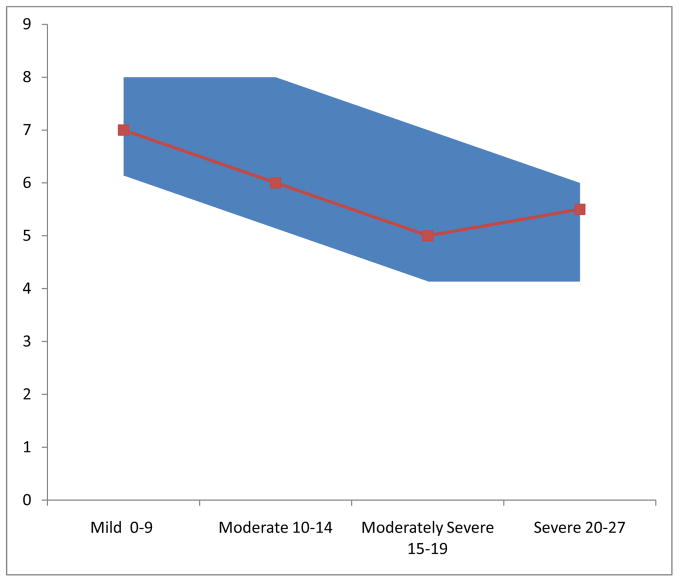

To provide practical implications of this data, we matched the weekly average of mood scores with PHQ-9 values. Drawing from the model constructed with weekly mood scores as the only predictor of PHQ-9, Figure 1 displays the PHQ-9 Depression severity category based on the interquartile range (IQR) of mood ratings. It is worth noting that in this sample the PHQ-9 scores had a mean of 9.12 (SD = 5.47).

Figure 1.

PHQ-9 Symptom Severity at different value of weekly mood rating averages

Discussion

Our results show that automatic text message based mood ratings can be a clinically useful proxy for the PHQ9. Importantly, this approach avoids the limitations of the PHQ9 administration, which include length and a higher requirement for literacy. Our findings suggest that mobile mood ratings can be used to track patients with depression over time simply, efficiently, and effectively.

It is worth noting that our findings drew from a sample that already were screened for depression and undergoing group therapy. The PHQ9 can play an important role in screening patients who might require treatment for depression (Gilbody, Richars, Brealey, & Hewitt, 2007). It assesses the full breadth of DSM 5 depression symptoms, and spans a larger timeframe. For adults, it is the recommended disorder specific severity measure according to the DSM 5 (APA, 2013). As such, it may be a good indicator of the persons overall state vis-a-vis depression; however, it may be too blunt of an instrument to measure how a person feels in the moment, or on specific days. The nimbleness of daily mood ratings may be more useful in the context of therapy as it can help to identify struggles and successes on specific days, which is helpful for understanding patterns and triggers.. Future research could investigate if daily mood ratings can help guide treatment decisions or predict eventual treatment response.

Mobile mood ratings, when assessed daily, may provide a more accurate indicator of longitudinal symptom levels than the PHQ9, as the PHQ9 may be subject to a recency bias. Our findings show that PHQ9 ratings are mostly related to the daily mood rating and may not actually reflect symptoms over two weeks. Although the DSM 5 requires depression symptoms be present for a minimum of two weeks, it may be likely that subjective symptom reporting may be influenced by the past weeks’ experience. This too should be the focus of future research. For clinicians, choosing whether to use the PHQ9 or a daily mood ratings, or both, should be based in pragmatics. PHQ9 is useful to measure total symptom level (e.g., for screening) or to monitor specific symptoms aside from mood; however, monitoring with the PHQ9 is likely to happen infrequently (when people come in to an appointment or therapy session), and lower-literacy individuals may require help or may neglect to complete it. Once treatment is underway, a single item question might be more useful as it can be provided more frequently. Repeated administration of a single item question provides a “high resolution” picture of a patient’s emotional life, tracking daily fluctuations and possibly hinting at important events or changes that might require clinical attention.

Limitations

Our findings have some limitations that should be noted. First, we assessed a group of depressed patients; though this is likely the intended audience for this measure, our mood ratings captured a more narrow range of depression symptoms than would likely be found in the general population. Our sample was Spanish speaking and from a low-income background, and although it may not representative of the larger population, it gives credence to the utility of this tool in low-income minority population. However, if a technology-based assessment can work in this population, it is likely to generalize toward a more tech savvy group. Finally, although the sample size was relatively small, it’s important to note that the longitudinal nature of the data provided many data points from which to base our conclusions.

Conclusion

Simple mood ratings are not intended to replace thorough symptom measures like the PHQ9, however, they offer a valuable tool for clinicians seeking to understand their clients mood states between sessions. It is important to know, however, how these forms of assessment correspond to each other. This study found that PHQ9 can be reliably predicted from single day or one-week averages of mood ratings. As digital health interventions are more widely implemented, mood ratings can serve many purposes including intervention and assessment. These tools are already being used as part of clinical practice and in a variety of interventions, and it is important to begin to recognize them as appropriate and valid outcome measures.

Highlights.

We compared text message based mood ratings with PHQ-9 scores.

PHQ-9 scores were most related to daily and one week mood ratings.

Automated text messaging mood ratings can serve as a clinically useful tool.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by: an NIMH grant (K23MH094442; PI: Aguilera), a Robert Wood Johnson New Connections grant (PI: Aguilera), NIMH grant K08 MH102336 (PI: Schueller), NIMH grant 5K08MH091501 (PI: Leykin) and a grant from the UCSF Academic Senate (Leykin, P.I.).

The authors would like to thank to Patricia Arean for her helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. We would also like to thank Julia Bravin, Omar Contreras and the Center for Behavioral Intervention Technologies at Northwestern University for their contributions to the execution of the project.

Role of the funding source

Dr. Aguilera’s K23 and the Robert Wood Johnson award funded the development of the technology based platform and the execution of the intervention. Dr. Schueller’s and Dr. Leykin’s funding supported their salary while working on this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The study authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributors

Adrian Aguilera designed and implemented the study. Stephen Schueller conducted the analyses and Yan Leykin aided in the preparation of the manuscript and framing of the issues.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Adrian Aguilera, University of California, Berkeley, University of California, San Francisco.

Stephen Schueller, Northwestern University.

Yan Leykin, University of California, San Francisco.

References

- Aguilera A, Berridge C. Qualitative feedback from a text messaging intervention for depression: Benefits, drawbacks, and cultural differences. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2014;2(4):e46. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera A, Muñoz RF. Text messaging as an adjunct to CBT in low-income populations: A usability and feasibility pilot study. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2011;42(6):472. doi: 10.1037/a0025499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Chatterji P, Wells K, Cao Z, Chen C, Takeuchi D, et al. Disparity in depression treatment among racial and ethnic minority populations in the united states. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59(11):1264. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.11.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Basch E, Torda P, Adams K. Standards for patient-reported Outcome–Based performance measures. Jama. 2013;310(2):139–140. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(11):1596–1602. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0333-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilsley J, Moffoot AP, O’Carroll R. An analysis of memory dysfunction in major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1995;35(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00032-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagomasino IT, Dwight-Johnson M, Miranda J, Zhang L, Liao D, Duan N, et al. Disparities in depression treatment for latinos and site of care. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(12):1517–1523. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.12.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, Krupnick J, Siddique J, Revicki DA, et al. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: A randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2003;290(1):57–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Cooper LA. Disparities in care for depression among primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19(2):120–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organista KC, Muñoz RF, González G. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in low-income and minority medical outpatients: Description of a program and exploratory analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1994;18(3):241–259. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Internet Project. Mobile technology factsheet 2014 [Google Scholar]