INTRODUCTION

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a recently developed optical analogue of ultrasound that measures the intensity of back reflected light rather than echoes of sound and translates these optical reflections into a high-resolution, two-dimensional tomographic image.1–3 Though OCT has many similarities to ultrasound, its use of light gives it some fundamental advantages. Because light has a much smaller wavelength than sound waves, the resolution of intravascular OCT is one to two orders of magnitude greater than IVUS.2–4 Also, the faster speed of light allows for a faster frame rate than ultrasound. Additionally, because OCT does not require a transducer, the catheter required for intravascular OCT imaging can be much smaller than that used for IVUS.5

However, OCT’s use of light waves has some fundamental disadvantages as well. As the frequency of energy increases, penetration depth decreases. Consequently, the smaller wavelength of light reduces OCT’s penetration depth markedly compared to that of ultrasound.3 This mandates OCT imaging to be restricted to superficial diseases due to a limited depth of penetration of light. For instance, for applications related to atherosclerosis, invasive intravascular catheters are required. Finally, because red blood cells scatter light,6–9 the vessel to be evaluated must be flushed before imaging can be performed,2 thus adding constraints to the imaging procedure.

This review will explain how investigators working with OCT in the cardiovascular system have capitalized on the advantages of OCT and dealt with the disadvantages. In part 1, we discuss the basic principles of light transport in cardiovascular tissue, the physics of OCT, and the basic design of a catheter-based, intravascular OCT system. Then, we address the various strategies of blood clearance during imaging and give recommendations based on our experience.

After the basics of OCT instrumentation have been covered, we review an aspect of cardiology that OCT is uniquely positioned to impact—the monitoring of coronary interventions. We present several high-resolution OCT images difficult to reproduce with other modalities, including complications (intramural hematomas and dissections), and demonstrations of the efficacy of procedures (such as cutting balloon angioplasty and stent placement).

In part 2, we delve into what is currently the most active clinical application of OCT in cardiology: late-stent thrombosis related to drug eluting stents (DES). The high resolution of intravascular OCT makes it the only imaging tool capable of monitoring the absence and thickness of neointima formation, ensuring OCT will be the tool that determines which next generation DES design will be ideal. Another clinical endpoint relevant to a larger patient population is the identification of vulnerable plaque. Though progress in identifying the vulnerable plaque has been made with other imaging modalities (e.g., calcium scores in CT and plaque burden and lipid measurements in IVUS), OCT is the only modality with sufficient resolution to identify fibrous cap thickness and the presence of macrophages. Current progress in identifying these features is reviewed.

OCT has cellular resolution in cell culture and simple intact tissues. This begs the question of whether or not cellular imaging can be performed in diseased human tissues with OCT. We review several attempts at cellular imaging of vulnerable plaque. Finally, future OCT technologies are reviewed to provide insight into what cardiologists might anticipate in the future.

OCT THEORY AND INSTRUMENTATION

A general understanding of tissue optics (the physics of light travel in tissue) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) is important for a better understanding of image generation and subsequent accurate interpretation of OCT images.

Attenuation of Light in Tissue due to Absorption and Scattering

Light is absorbed as it travels through tissue. The amount of light absorbed is determined by Lambert-Beer’s law:10:

where d denotes the distance that light travels through tissue, I0 denotes the light intensity incident on the tissue, and µa denotes the absorption coefficient of the tissue.

However, attenuation of light in tissue is not due to absorption alone. A second component of attenuation, scattering, also causes the decay of light in an exponential fashion and can also be treated as a Lambert-Beer’s law decay. Thus, the total attenuation of light travelling through tissue can be thought of simply as:11:

Near-Infrared “Window” of Low Absorption

The absorption coefficient varies for different tissue components and wavelengths of light. Most tissue components have relatively low absorption in the wavelength range from 700 to 1400 nm, which are the wavelengths of OCT systems. Thus, issues of light attenuation in tissue are in part mitigated by the near-infrared “window” of low absorption.

A sample absorption spectrum for water is shown in Figure 1. Note the lack of water absorption in the visible wavelengths (you can “see through” water with visible light) but that the absorption increases in the near-infrared wavelengths (it is more difficult to “see through” water in the near-infrared range where OCT operates). A comparable absorption spectrum for hemoglobin is also shown in Figure 1. Note that hemoglobin absorbs strongly in the visible light spectrum but there is a decrease in absorption as the wavelength increases. Since cardiovascular tissue is composed primarily of water and chromophores like hemoglobin, a “window” of low tissue absorption exists between 700 and 1400 nm where both water and chromophores like hemoglobin, lipid, and arterial tissues have relatively low absorption. OCT uses light in this near-infrared window and thus achieves greater imaging depths. In the cardiovascular system, these imaging depths are on the order of 2–3 mm.2

Figure 1.

Absorption coefficients of water and hemoglobin in the visible and the near-infrared. Water is almost perfectly transparent in the visible wavelengths, but begins to absorb strongly as the wavelength increases in the infrared. The absorption of hemoglobin is similar to lipid and arterial wall components. Note the overall decrease in absorption of hemoglobin as the wavelength increases in the near-infrared (reproduced with permission from12).

Mismatch of Index of Refraction causes Back-Reflections

The creation of an image with OCT is similar in many ways to the creation of an image with ultrasound. An ultrasound probe sends a beam of sound deep into tissue and collects echoes of sound from structures with different acoustic impedances. A 2-dimensional image of echo intensities is created by the ultrasound system.

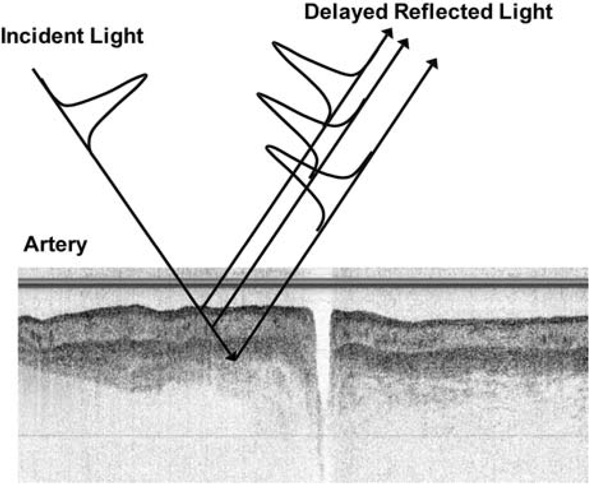

In OCT, a beam of light is aimed at tissue and the light is reflected back from the tissue by structures that have a different optical indices of refraction. A grayscale image of reflected intensity is created by the OCT system (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

An OCT image is a gray scale image of the intensity of back reflected light from deep in a peripheral artery (adapted from images courtesy of Drs. Roger Gammon and Frank Zidar, Austin Heart Hospital, Austin, Texas).

Need for an Interferometer

However, a key difference exists between ultrasound and OCT. Sound waves are slow enough so that echoes may be detected by electronic instrumentation. However, light waves are so fast, and the distances measured so small, that current electronic technology cannot differentiate light reflections from different depths in the tissue. Thus, OCT detection of back-reflected light is based on techniques that compare the back-reflected light signal to a reference light signal traveling a known path length. This technique is called low-coherence optical interferometry.

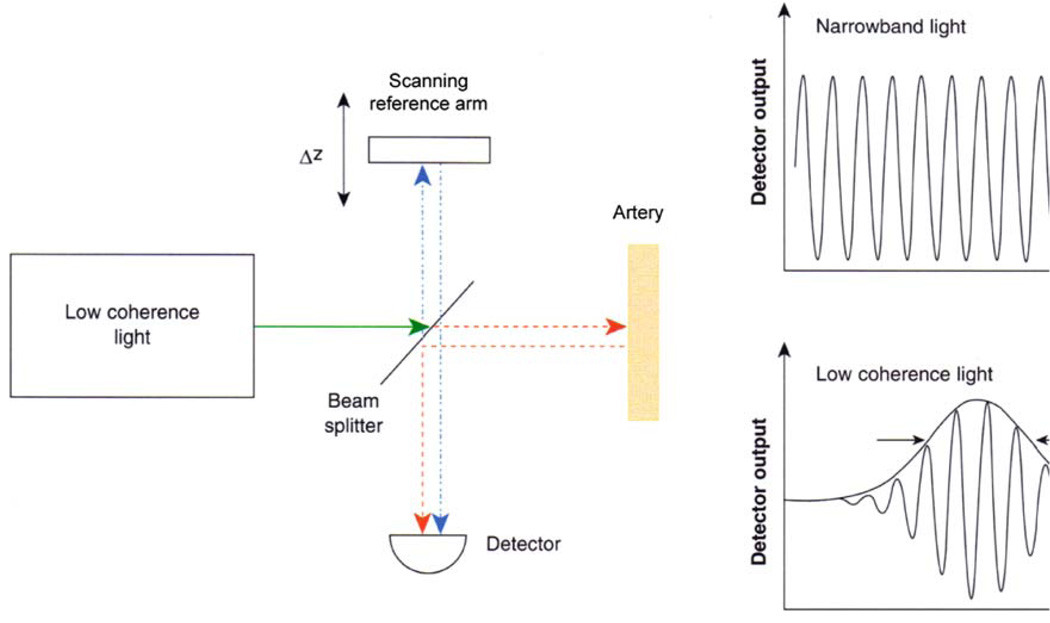

Simple OCT System

Figure 3 shows a simple schematic of low-coherence, optical interferometer. The interferometer works in the following manner: a light source sends a beam of light to a beam splitter in the center of the interferometer. The beam of light is split and is sent in two directions—half to the reference mirror and half to the tissue. Back-reflections from the tissue combine with reflections from the reference mirror at the beam splitter and enter a detector. The two sets of reflections interfere with each other when their path lengths are the same. The detector senses this interference and converts it into a signal that, after processing, will become the OCT image.

Figure 3.

Schematic of a low-coherence interferometer used for time-domain OCT. Back-reflected light from the tissue being imaged interferes with light traveling a known reference path. The mirror in the reference path is mechanically scanned in order to produce a time-varying change in path length. When a low-coherence light source is used, interference will be observed only when the reference and tissue path lengths are the same. This time domain detection method measures back-reflections sequentially at different depths in the tissue as the reference mirror is scanned (adapted with permission from2).

The axial resolution (in depth) is determined by the bandwidth of the coherent light source used for imaging. Current OCT technologies have resolutions from 4 to 20 µm.4

Scanning

In a time domain implementation of OCT (Figure 3), the reference mirror moves back and forth causing the reference path to get shorter and longer with time. This has the effect of scanning in depth in the tissue. This reflectivity profile, called an axial scan (A-scan), contains depth information about the structures within the tissue. A cross-sectional image (B-scan), similar to B-mode ultrasound, may be achieved by laterally scanning the tissue and creating a series of these axial scans (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Scanning pattern used to create a B-scan OCT image. Serial axial reflection measurements (in depth) are performed as the tissue is scanned in the lateral direction. The result is a 2-dimensional image analogous to B-mode ultrasound. (Adapted from images courtesy of Drs. Roger Gammon and Frank Zidar, Austin Heart Hospital, Austin, Texas).

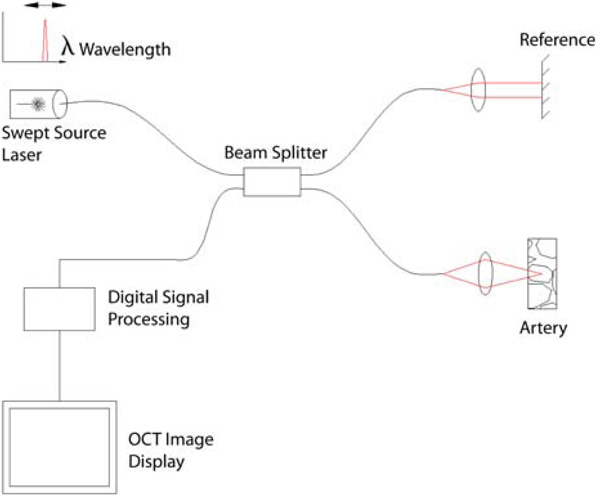

Fourier Domain OCT

A simple schematic of a swept source OCT system based on a fiber optic, dual beam interferometer is shown in Figure 5. Time domain OCT utilizes a mechanically scanning mirror in the reference path in order to scan the tissue in depth. Swept source OCT, on the other hand, uses a frequency scanning light source (i.e., a frequency scanning laser) in the optical setup that assumes the duty of scanning in depth. This results in a more efficient use of light and provides dramatically higher imaging speeds. Other related techniques including spectral domain and optical frequency domain imaging (OFDI), accomplish the same increase in imaging speed with slightly different techniques.

Figure 5.

A schematic of a swept source OCT system, a type of Fourier domain OCT that provides much faster imaging speeds than time-domain OCT (adapted from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ss-oct.PNG).

The Light Lab M2x® OCT imaging system, currently the only commercially available OCT system, is an example of a time-domain device. The Volcano CorVue® OCT imaging system is an example of a soon-to-be available Fourier domain system that has dramatically higher imaging speeds than time domain systems and thus a reduced need for flushing of the vessel during imaging.

Intracoronary Technique

Because OCT technology is based on fiber optics, it can be interfaced with many optical probes including catheter-based probes. The CorVue® catheter from Volcano (Figure 6) has an optical fiber encased in a hollow cable coupled to a distal lens and a microprism that directs the OCT beam radially outward from the catheter as the catheter tip spins. The cable and optics are encased in a transparent housing. A cross-sectional image of the artery is created by spinning the cable inside the transparent housing. Imaging may also be performed in a longitudinal plane by a proximal-distal, push-pull movement of the fiberoptic cable assembly (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

A 3.2 Fr CorVue® catheter tip from Volcano Corporation. A rotating optical fiber coupled to a distal lens and microprism are encased in transparent housing that inserts over a guide wire. As the optical cable spins, the OCT beam is directed radially outward toward the vessel wall (courtesy of Volcano Corporation, San Antonio, TX and Rancho Cordova, CA).

Figure 7.

A Catheter tip is positioned in the vessel distal to the lesion. Note that blood, a strong scatterer of light, fills the lumen of the vessel. B Imaging begins. As the catheter tip spins (blue whirl), the OCT beam is aimed radially outward toward the vessel wall to create a cross-sectional image of the vessel. A 50:50 mixture of saline: Iodixanol (Visipaque®) is injected to clear red blood cells from the imaging field. C The catheter tip is pulled back proximally. The tip continues to spin and, in a reduced red blood cell environment, captures a cross-sectional image of vessel pathology and the associated intervention (courtesy of Volcano Corporation, San Antonio, TX and Rancho Cordova, CA).

At our institution, we use the Volcano CorVue® Fourier domain OCT system (Figure 5) which has a center wavelength of 1310 nm, frame rate of 20 frames per second, 1000 axial scans/frame, up to 10 mm/second pullback speed, a 30 µm lateral resolution, and a 15 µm axial resolution. The system interfaces with a 3.2 Fr catheter with a rotating distal tip (Figures 6 and 7). The porcine images shown in Figures 9, 14, 15, and 18–21 of this review were obtained at our institution with this imaging system.

Figure 9.

Saline versus 50:50 saline:Iodixanol (Visipaque ®). Before flushing, light scattering by red blood cells prevents imaging of the vessel wall. After flushing with saline or saline/contrast mixture, red blood cells are removed from the imaging field and the vessel wall is apparent. Note the earlier, longer, and more complete clearance of RBCs by the saline/contrast mixture. Both imaging studies were performed in the LAD of a 70 kg pig with flushing at 4 mL/second with power injection (Medrad Mark IV power injector, Medrad Inc, Pittsburgh), total 20 mL flush. Images taken with the Volcano CorVue® Fourier Domain OCT system (Volcano Corporation, San Antonio, TX and Rancho Cordova, CA).

Figure 14.

Evidence of underdeployment of stents in a live porcine coronary artery. At 12 and 2 o’clock, three edges of the stent strut are evident in the left panel. The Liberte stent strut is 96 µm. If this distance is added to the leading stent strut edge identified with OCT, contact with the lumen wall is still not evident. The right panel demonstrates at 10 o’clock three edges of Taxus stent struts which are 132 µm thick and also mildly underdeployed. Scale: the central structure in the lumen of the vessel is the CorVue OCT catheter system® which has a known diameter of 1.13 mm (courtesy of Volcano Corporation, San Antonio, TX and Rancho Cordova, CA).

Figure 15.

LAD of a 46 kg pig which first received a Liberte bare metal stent (96 µm stent, thin arrow), and subsequently a second Taxus drug eluting stent (132 µm, thick arrow). OCT images taken with the CorVue® Fourier Domain OCT System (Volcano Corporation, San Antonio, TX and Rancho Cordova, CA).

Figure 18.

Jailed side branches in a live porcine model immediately following stent placement are identified with OCT. This two figure panel demonstrates two extremes in jailed side branches. The left panel shows a single stent strut covering a jailed side branch, which should allow easy passage of a 0.014 inch angioplasty guide wire to access the side branch. In contrast, the right panel identifies multiple stent struts covering a jailed side branch, which would predict the inability to wire the side branch successfully. These image pairs demonstrate a future use of OCT—the ability to understand the mechanism of jailed side branches which cannot be crossed with an angioplasty wire (courtesy of Volcano Corporation, San Antonio, TX and Rancho Cordova, CA).

Figure 21.

Tissue prolapse is evident following stent placement. Note the lack of light scattering in the abluminal side of the tissue prolapse, indicating that it is not a red thrombus (courtesy of Volcano Corporation, San Antonio, TX and Rancho Cordova, CA).

BLOOD CLEARANCE (FLUSHING)

The development of optical imaging catheter systems for use in blood vessels has been solved. However, the problem of light scattering by blood must be solved in order for OCT to be a useful clinical tool in cardiovascular medicine.

OCT sends a beam of light toward the vessel wall and collects reflected light returning from the vessel wall. During this process, the light must make two passes through blood in order to be collected by the OCT probe. Since the red blood cells (RBCs) are strong scatterers of near-infrared light, RBCs must be reduced in the imaging field for adequate OCT imaging to be performed. The first attempt at in vivo imaging was by Fujimoto et al5 who flushed a rabbit aorta with saline to obtain blood clearance. Since then, many attempts have been made to provide an optimal blood clearance technique which allows for adequate imaging while minimizing ischemic time and reducing the risk of contrast nephropathy when the latter is used. Only after an acceptable clearance technique is arrived at will widespread acceptance of OCT imaging in the coronary catheterization lab be attained. The most recent OCT advance related to solving issues of RBC clearance is the more efficient use of light by the previously mentioned Fourier domain OCT techniques. These more efficient OCT approaches have significantly reduced the amount of flush required to perform intravascular imaging due to a dramatic decrease in the amount of time required to obtain an image.

Red Blood Cell Scattering

Earlier in this review, it was demonstrated that near-infrared (NIR) absorption by hemoglobin is minimal. However, light attenuation in blood is significantly higher than that expected from hemoglobin absorption alone.6,7 This indicates that RBC scattering is the predominant mechanism of light attenuation (Figure 8). Scattering of blood in the near-infrared is due to the differences in index of refraction inside and outside the red blood cell, the bi-concave shape of the red blood cell, the wavelength of light, and the hematocrit.7–9

Figure 8.

Optical properties of several dilutions of murine blood with Oxyglobin®. The reduced scattering coefficient is dependent on the number of RBCs per unit volume. The absorption coefficient (µa) depends on the concentration of hemoglobin. Hct indicates hematocrit (reproduced with permission from6).

Four Strategies to Minimize Light Scattering during OCT Imaging

An ideal flushing solution would reduce the scattering of light by RBCs while minimizing ischemia times required for imaging. Based on the above mechanisms for light scattering by RBCs, four basic clearance strategies can be used to minimize light scattering during OCT imaging: (1) reduction in the number of RBCs (hematocrit reduction), (2) displacement of RBCs with a highly viscous fluid, (3) index matching between plasma and the RBC, and (4) organizing RBCs into rouleaux formations.

(1) Reduction of hematocrit to below 10%

Results presented in Figure 8 indicate that RBCs are a significant source of light scattering and a minimal source of light absorption. Thus, a marked reduction in hematocrit is required for light to penetrate and reflect the distance needed to image deep within the vessel wall. Our group first encountered the problem of light attenuation by RBCs when attempting to image the murine myocardium. In order to solve the problem of RBC scattering, we reduced the hematocrit of the mouse with an artificial blood substitute which is a solution of free hemoglobin without particulate material. In this way, we reduced the hematocrit of a mouse from physiologic values (~45%) to <10% and were able to image the anterior right ventricular myocardium with OCT. These results are consistent with Roggan et al that suggest that reduction of scattering only occurs at a hematocrit of <10%.7 Despite the advantage that hemoglobin-based blood substitutes offer by carrying oxygen to prevent tissue ischemia, they are problematic in that none are currently FDA approved and have resulted in worse clinical outcomes in certain patient populations.13

Other investigators imaging in vivo rabbit aorta solved the problem of blood attenuation by flushing the aorta with saline, thereby temporarily reducing the hematocrit for a few seconds.5 Saline flushes result in a dilution of RBCs thereby eliminating scattering by temporarily reducing the hematocrit. However, saline flushes are not optimal because they result in transient tissue ischemia. Although not problematic for the peripheral circulation, imaging of cerebral and coronary vessels may be problematic with saline flushing.

To address this issue further, there is reassuring evidence concerning the safety of infusing large volumes of saline into patient coronary arteries which is apparent from the laser angioplasty literature. Patients have safely received 45–180 mL of intracoronary saline without clinical complications (assuming laser pullback rate of 0.2–0.5 mm/second, lesion length of 18 mm, and injection rate of 2 mL/second).14–17 Further, Deckel-baum et al18 safely power injected an average of 48 mL of saline during laser angioplasty (assuming laser pull-back rate of 0.5 mm/second, lesion length of 12 mm, and injection rate of 2 mL/second). Thus, the injection rates and volumes discussed above, while causing angina and ECG changes, do not result in untoward clinical events.

(2) RBC displacement by a highly viscous fluid

An alternative in vivo approach would be the use of agents with high viscosity. High viscosity agents are anticipated to improve blood clearance due to more efficient transfer of displacement energy to move RBCs out of the imaging field, while delaying RBC reappearance in the imaging field. Prati et al19 have performed in vivo OCT imaging using a 50:50 solution of saline and Iodixanol (Visipaque®, GE Healthcare) and achieved excellent image quality. No balloon occlusion was utilized despite the use of the LightLab® time-domain system. They hypothesized that Iodixanol being the most viscous of contrast agents contributed to their success. A second clinical benefit of Iodixanol is its lower nephrotoxicity.

Figure 9 shows two imaging studies performed at our institution using 100% saline and a 50:50 mixture of saline and Iodixanol in a porcine LAD. No balloon occlusion was needed as the images were taken with a Fourier Domain OCT system (Volcano CorVue®, Volcano Corporation, Rancho Cordova, CA). Our results confirm the superiority of a high viscosity solution over saline.

Despite the appeal of using pure contrast as an agent to clear RBCs, hand and power injections of pure Iodixanol through a 6 Fr guiding catheter containing the CorVue® Volcano OCT system are not practical due to excessive resistance of the minimal remaining catheter lumen (personal experience). Thus, dilutions of Iodixanol will be required to practice this approach. A comparison of different dilutions on in vivo image resolution versus renal toxicity (saline:contrast ratios of 25:75, 50:50, and 75:25), and determining the precise viscosity of these different dilutions has not been performed to date.

(3) Index matching between plasma and RBCs

Another approach to reduce light scattering by RBCs is index of refraction matching. The cause of light scattering is the difference in the index of refraction between plasma and RBCs. There have been several studies which have attempted to raise the index of refraction of plasma to equal that of RBC cytoplasm to reduce light scattering. Brezinski et al20 demonstrated improved OCT light penetration in ex vivo chambers simulating blood flow when index of refraction matching was performed with contrast (Hexabrix—low viscosity compared to Iodixanol) and dextran (Figure 10). This approach, however, has not been translated into a clinically successful method for reducing light scatter in vivo to date.

Figure 10.

Upper panel: reflector (mirror) was placed in tubing as shown. Section of reflector imaged is 2 mm below inner surface of tubing. Once blood was introduced into system and circulated, OCT imaging of reflector was performed. Lower panel: summary of the impact of dextran, contrast, and saline on light penetration. For saline control, a 7 ± 3% increase in signal intensity was noted (not statistically significant). An increase of 69 ± 12% was noted for dextran, which was statistically different from the saline control (P < .001). For contrast, a 45 ± 4% increase was noted, which was statistically different from control (P < .005) (reproduced with permission from20).

(4) RBC rouleax formation

A final mechanism to reduce light attenuation by blood is the formation of RBC rouleaux and rouleaux networks (organized aggregates of RBCs). Dextrans can be used to artificially induce aggregation of RBCs by bridging surfaces of adjacent cells after adsorption on their surfaces.21,22 By forming well organized aggregates, light scattering by blood is reduced.23 However, at low concentrations of dextran, these RBC aggregates form, while at high concentrations of the identical molecular weight dextran, dis-aggregation of RBCs occurs. Further, the degree of aggregation increased in vitro overtime and was maximal at 15 minutes (the last time point examined). Finally, all of Xu et al23 studies were performed in vitro, without flowing blood. Thus, it is unclear how this mechanism of rouleaux formation would translate into clinical practice (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Microscopy images for blood with added dextran saline solution (1.62 g dL-1). Images are taken 15 minutes after the addition of saline control, D ×10, D ×70, and D ×500. Aggregation was time-dependent. Higher molecular weight dextrans induce greater aggregation (reproduced with permission from23).

For instance, a hard hand flush in a coronary artery may be too quick for the advantages of aggregation to be realized. Further, different results related to aggregation and dis-aggregation will be obtained based on the concentration of the dextran solution injected.

Dextran Solutions combine several Mechanisms of Clearance

Dextrans combine several of the mechanisms discussed above to reduce light scatter of RBCs. First, dextran reduces the difference in refractive index between plasma and the cytoplasm of the RBC. Several groups20,23 have postulated that the increase in light penetration caused by dextran is due, in part, to refractive index matching. However, dextran is also a viscous fluid and a second mechanism of clearing is the displacement of red blood cells similar to Iodixanol. A third potential mechanism of clearance is the formation of rouleaux and rouleaux networks as shown by Xu et al23

Thus, for multiple reasons, dextrans appear to be the most appealing agents to use for reduced light scattering of blood. However, despite their appeal, there have been no studies to date reporting dextran use in intact animal models or patients. Dextran is currently used clinically as an intravenous volume expander and anticoagulant. Dextran is available as an injectable and has FDA approval for intravenous use only. However, dextran does not have FDA approval for intracoronary use to date.

Occlusive versus Non-Occlusive Techniques

Currently, the only commercially available OCT system is a time-domain system from LightLab®. Their image acquisition process typically uses proximal vessel occlusion by means of gentle balloon inflation plus vessel flushing with saline infusion during imaging. This technique is rather cumbersome and time consuming which does not encourage its routine use.24 To overcome this limitation Prati et al19 developed a simplified method for OCT acquisition that does not require vessel occlusion. Their infusion protocol required a manual injection of a commercially available contrast (Iodixanol 320, 50:50 dilution with saline) from the guiding catheter resulting in blood being completely displaced from the artery during the entire image acquisition period. In 60 out of 64 patients, the imaging procedure was successful. The mean image acquisition time was 5.3 ± 1.4 minutes. They reported no major complications such as death, myocardial infarction, or major arrhythmias. Their results suggest that balloon occlusion may not be necessary even considering the long imaging (and thus, ischemia) times necessary with time domain OCT. It should be noted that as both LightLab and Volcano Corporation transition to Fourier, Spectral, and OFDI systems, there will be a significant reduction in imaging and flushing times as demonstrated by Tearney et al,25 as well as by our group (Figure 9).

Power Injection versus Hand Injection

The use of power injection in coronary arteries has been proposed as a method to accomplish blood clearance during OCT imaging. During the early years of coronary angiography (1970s), many physicians used power injectors. Reduction of this practice has occurred due to a transition to the use of hand injections. The main motivating factors for switching to hand injections have been convenience and cost.

The complication rates between hand and power injection of coronary arteries are similar. The major complications of hand injection used during routine cardiac catheterization include the risk of death, myocardial infarction, coronary dissection, and embolization, which range between 0.08 and 0.14%.26–29 To demonstrate that published complication rates during power injection are similar, the following studies were located. Koppes30 published their 5 year data in 1498 patients, using power injection and reported a complication rate of death (0.067%), myocardial infarction (0.2%), coronary occlusion (0.67%), and coronary dissection (0%). Ireland et al31 published their data on power injection in coronaries in 5,887 patients. There were only five dissections (0.08%) and one air embolism (0.01%), a rate similar to that reported in earlier studies of power injection.32

Cardiologist’s major concern with power injection is the incorrect assumption that there is a lack of control over the force of injection and a subsequent increased risk of dissection due to dangerously high pressures. Studies have shown that the pressures generated during forceful (Hard, see Table 1) hand injections are similar to those generated during power injections (4 mL/second, see Table 1). Further, the lower standard deviations with power injection are consistent with less variation than with hand injection. Gardineret al33 have demonstrated safe injection (Medrad Mark IV power injector, Medrad Inc, Pittsburgh) of 4–6 mL/second in left coronary system and 3–5 mL/second in right coronary system. As a result, these have become the clinically accepted power injection rates currently employed. Our successful imaging with the CorVue® Volcano OCT system during power injection of 6 mL/second implies that we are operating in a safe and clinically acceptable range (unpublished data).

Table 1.

Demonstration that pressures achieved with hand injection are similar to those obtained with power injection

| Method of injection | Pressure (psi) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power injection | Injection rate | 2 mL/second | 3 mL/second | 4 mL/second |

| Judkins 7F | Mean ± SD | 106 ± 3 | 130 ± 1 | 136 ± 2 |

| Range | 102–110 | 128–130 | 135–140 | |

| Sones 8F | Mean ± SD | 61 ± 1 | 97 ± 3 | 106 ± 1 |

| Range | 60–63 | 93–100 | 105–10 | |

| Hand injection | Force of injection | Soft | Medium | Hard |

| Judkins 7F | Mean ± SD | 50 ± 9 | 89 ± 22 | 128 ± 16 |

| Range | 30–65 | 50–110 | 105–160 | |

| Sones 8F | Mean ± SD | 61 ± 12 | 82 ± 6 | 106 ± 16 |

| Range | 40–80 | 75–90 | 90–130 |

Reproduced with permission from.31

Recently, the use of 4 and 5 Fr diagnostic catheters have become popular to reduce groin complications and allow early ambulation. The angiographic images obtained with these catheters using hand injections are suboptimal due to increased resistance from the reduced internal diameter of the lumen of these catheters. As a result, a new power injection company has developed to support this need. Acist system® (Acist Medical Systems, Minnesota) was developed for the power injection of coronaries using smaller French size catheters. The Acist system® has been shown to be safe and effective in performing coronary angiography, with no coronary dissections reported to date.34–38 However, there have been no studies to date testing whether the Acist system will be useful when coupled with OCT imaging.

Fourier, Spectral Domain, and OFDI OCT will Reduce Flushing Times

The use of the LightLab® time domain OCT system has been examined by several groups internationally.19,39,40 Time domain systems are somewhat limited in their efficiency of light utilization and require slower pullbacks of 1 mm/second to allow adequate collection time of reflected light. In these studies, displacement of blood was achieved by either the combination of balloon occlusion with hand flushing with saline, or hand injection of saline without balloon occlusion. The latter approach provides only a few seconds of adequate image acquisition, and thus only short segments of the coronary artery can be imaged (22–31 mm).19 Yamaguchi et al41 have shown that, with the balloon occlusion and saline flush technique, they can safely image for up to 30 seconds which translates into interrogation of a 30 mm segment of the coronary. However, there are concerns related to this technique including both barotrauma and ischemia due to the occlusion balloon. Serruys and coworkers42 have reported using both flushing techniques, but predominantly the balloon occlusion technique. They reported transient ECG changes in all patients and 75% of patients reported angina. Total flush volumes were up to 100–150 mL/patient during evaluation of all three coronary arteries. It is anticipated that the more efficient use of light with Fourier domain/Spectral domain/OFDI imaging approaches, with pullback rates of up to 10 mm/second, will allow the use of less saline and interrogation of longer segments of the coronary artery without balloon occlusion.

IMAGING CORONARY INTERVENTIONS

Stent Mal-Apposition

Mal-apposition is defined as a single stent strut failing to make contact with the vessel wall. Kume et al43 demonstrated that the ability to assess apposition of stent struts in a cadaver specimen with OCT was superior to IVUS. Thus, OCT provides a level of resolution not previously available with IVUS, and as a result, the development of new grading criteria to assess stent strut apposition is needed.

Two OCT classification systems for stent mal-apposition have been proposed based on evaluation months after stent placement. The first, by Matsumoto et al44 classified the strut/vessel wall relationship into one of the three categories: (i) well-apposed to vessel wall with neointimal coverage, (ii) well-apposed to vessel wall without neointimal coverage, and (iii) mal-apposed to the vessel wall without neointimal coverage. A stent strut was classified as mal-apposed when the distance between its leading edge reflection and the vessel wall was greater than the actual thickness of the strut. Thus, this classification scheme requires knowledge of the strut thickness of each commercial stent since the strut surface most distant from the light source is not visible. Representative images of the three strut categories are shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Classification of drug eluting stent (Cypher®) strut conditions by OCT. A, Well-apposed with neointimal coverage. B, Well-apposed without neointimal coverage. C, Mal-apposed without neointimal coverage (reproduced with permission from44).

A more complex classification system has been proposed by Guagliumi and Sirbu45 based upon the interaction between the intimal hyperplastic tissue and the stent strut. Rather than define a stent strut as either being covered or not covered with intimal hyperplasia,43 Guagliumi further subdivided neointimal coverage into an additional three categories—strut deeply embedded in the neointima, superficially embedded in the neointima, or neointimal coverage which protrudes into the lumen. Figure 13 presents this classification scheme.

Figure 13.

Classification of strut/vessel wall apposition by OCT. Frames A–E represent Types I, II, IIIa, IIIb, and IV, respectively. A, Totally embedded strut (Type I). B, Embedded subintimally without disruption of lumen contour (Type II). C, Completely embedded with disruption of lumen contour (Type IIIa). D, Partially embedded with extension of strut into lumen (Type IIIb). E, Complete strut mal-apposition (blood able to exist between strut and lumen wall) (Type IV) (reproduced with permission from45).

Stent Underdeployment

Underdeployment is defined as multiple stent struts failing to make contact with the vessel wall. With OCT, assessment of apposition is accomplished by measuring the three visible edges of a strut. If the position of the abluminal edge of the strut is farther from the vessel wall than the known strut thickness, the strut does not made contact with the vessel wall. A stent found on OCT to have multiple consecutive struts that fail to make contact with the vessel wall is classified as underdeployed (Figure 14).

Stent Overlap

The ability to visualize superimposed stent struts, as well as gauge their thickness, has not previously been possible in vivo before the advent of OCT. As demonstrated in Figure 15, the thin nature of the Liberte stent struts is visually apparent compared to the thickness of the Taxus stent struts. The difference in thickness is only 36 µm, which is apparent with OCT. Further, three sides of many stent struts are evident as well as their cuboidal structure. This degree of resolution has previously been available only at autopsy in histologic images.

Biodegradeable Stents

Biodegradable stents are radiolucent and cannot be visualized by angiography like metal stents. OCT can be used as a substitute for angiography in these cases.47,48 Additionally, determination of the time course of reabsorption of biodegradable polymers in vivo in patients, and in animals models without sacrificing the animal is now possible due to the advent of OCT. As demonstrated in Figures 16 and 17, not only is the biodegradable stent visible immediately after placement, but the time course and morphological changes of the stent are visible with OCT.46 The ability to obtain these sorts of images will provide researches with rapid feedback regarding improvements in polymer and stent design, without the use of histology other than as a confirmatory tool.

Figure 16.

Bioabsorbable everolimus eluting coronary stent is shown in the left panel, and the same stent immediately following deployment in a patient is imaged with OCT in the right panel (ABSORB trial) (reproduced with permission from46).

Figure 17.

Four patterns of dissolution for bioabsorbable stents evidence with OCT imaging are shown (reproduced with permission from46).

Jailed Side Branches

See Figure 18.

Dissections

Dissections which occur at the time of angioplasty are important predictors of short-term complications. For instance, dissections from balloon angioplasty as well as at the edges of a recently placed stents are predictors of acute vessel and stent closure within minutes to hours following intervention. Previously, angiography and IVUS have been used to identify these dissections, but have lacked the resolution to image the more subtle dissections. Whether more subtle dissections identified with OCT will have the same clinical implications is unclear. We have frequently identified subtle dissections in the live porcine model with OCT which were not evident with angiography. Figure 19 is an example of a large dissection which includes both the intima and a portion of the media. The ability to image which anatomic layer of the vessel wall is involved in a dissection will provide new opportunities to classify dissections and perhaps provide more precise predictions of clinical outcomes, i.e., which dissections will heal and which will cause untoward outcomes.

Figure 19.

LCx artery in a live 50 kg pig which had an oversized balloon inflated (balloon: artery ratio of 1.3:1.0) with a resultant medial tear is shown. OCT images taken with CorVue® Fourier Domain OCT System (Volcano Corporation, San Antonio, TX and Rancho Cordova, CA).

Intramural Hematomas

Intramural hematomas are complications of coronary interventions and have been difficult to identify in vivo with IVUS. As demonstrated in Figure 20, OCT allows the identification of this complication, with identification of the actual tear in the intima (see white arrow), as well as the exact size and extent of the hematoma. In Figure 20, an RBC clearing flush rapidly entered the hematoma and rendered it transparent to OCT, allowing visualization of the entire extent of the hematoma. This finding indicates there is active communication between the lumen and the hematoma.

Figure 20.

LAD from a live 50 kg pig which was overinflated with a balloon. The arrow identifies the intramural hematoma. The markedly improved resolution of OCT allows for enhanced details such as the tear and blood collection created by an oversized balloon. OCT image taken with CorVue® Fourier Domain OCT System (Volcano Corporation, San Antonio TX and Rancho Cordova, CA).

Tissue Prolapse

It is often difficult to differentiate thrombus versus tissue prolapse immediately following stent placement, especially in patients with acute coronary syndromes. IVUS has not been able to make this differentiation.49 In Figure 21, the prolapsing material cannot be red thrombus due to the lack of light scattering on the abluminal side of the material or shadowing beneath in the vessel wall. Thus, the treatment of this tissue prolapse might be placement of a second stent to increase vessel wall coverage, an option which would not be considered if red thrombus were present.

Cutting Balloon Angioplasty

See Figure 22.

Figure 22.

Before (left) and after (right) cutting balloon angioplasty. This figure shows the classic appearance of a cutting balloon angioplasty on intimal hyperplasia within a previously placed stent. Prior to intravascular imaging with OCT, the scored cutting ability of this balloon had only been demonstrated with ex vivo tissues, but with OCT, the scored cutting can be visualized in patients (reproduced with permission from50).

Atherectomy

Figure 23 shows OCT images of infrapopliteal vessels, 2.5–3.5 mm in diameter, from a patient with critical limb ischemia. These images were taken with the NightHawk® catheter, which consists of a SilverHawk® SS + catheter equipped with OCT imaging. The NightHawk® allows for continuous, live OCT imaging of the vessel wall during excisional atherectomy. The ability to see all three diseased anatomic layers of the vessel wall in real time during atherectomy could dramatically improve the efficacy and safety of this technique. This example demonstrates how OCT will be incorporated into interventional devices in the future to provide additional information to the operator.

Figure 23.

Upper panel: longitudinal OCT image of an infrapopliteal vessel. This image was generated by an OCT system incorporated within the NightHawk®. This investigational device lacks a spinning tip, so images are made by push-pulling the catheter in the proximal-distal directions. Note the ability to discriminate the three anatomical diseased vessel layers: intimal hyperplasia, media, and adventitia. Lower panel: atherectomy was performed with the NightHawk®. Note the ability to determine the extent of the excision, consistent with OCT providing immediate feedback to the operator regarding the depth of cutting (courtesy of Dr. Roger Gammon and Dr. Frank Zidar, Austin Heart Hospital, Austin, TX).

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the following people: Dat Do, Fermin Tio, Steven Bailey, Thomas Milner (The University of Texas), Nate Kemp, Austin McElroy, Dan Sims, Joe Taber, Parker Wood, Joe Piercy, Larry Dick, Silbiano Gonzales, Paul Castella, Chris Banas (Volcano Corporation).

This work was funded in part by a VA Merit Grant (MDF), NIH Training Grant #HL07446 (JWV), and Volcano Corporation, San Antonio, TX and Rancho Cordova, CA.

References

- 1.Huang D, Swanson EA, Lin CP, Schuman JS, Stinson WG, Chang W. Optical coherence tomography. Science. 1991;254:1178–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.1957169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regar E, van Leeuwen TG, Serruys PW, editors. Optical coherence tomography in cardiovascular research. 1st ed. London: Informa Healthcare; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouma BE, Tearney GJ, editors. Handbook of optical coherence tomography. 1st ed. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang C. Molecular contrast optical coherence tomography: A review. Photochem Photobiol. 2005;81:215–237. doi: 10.1562/2004-08-06-IR-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujimoto JG, Boppart SA, Tearney GJ, Bouma BE, Pitris C, Brezinski ME. High resolution in vivo intra-arterial imaging with optical coherence tomography. Heart. 1999;82:128–133. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.2.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villard JW, Feldman MD, Kim J, Milner TE, Freeman GL. Use of a blood substitute to determine instantaneous murine right ventricular thickening with optical coherence tomography. Circulation. 2002;105:1843–1849. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014418.99708.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roggan A, Friebel M, Dorschel K, Hahn A, Muller G. Optical properties of circulating human blood in the wavelength range 400–2500 NM. J Biomed Opt. 1999;4:36–46. doi: 10.1117/1.429919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Twersky V. Absorption and multiple scattering by biological suspensions. J Opt Soc Am. 1970;60:1084. doi: 10.1364/josa.60.001084. 1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinke JM, Shepherd AP. Role of light-scattering in whole-blood oximetry. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1986;33:294–301. doi: 10.1109/tbme.1986.325713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishimaru A. Wave propagation and scattering in random media. 1st ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van De Hulst HC. Multiple light scattering: Tables, formulas, and applications. 1st ed. Volumes 1 and 2. New York: Academic Press; 1980. (Hardcover) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weissleder R. A clearer vision for in vivo imaging. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:316–317. doi: 10.1038/86684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Natanson C, Kern SJ, Lurie P, Banks SM, Wolfe SM. Cell-free hemoglobin-based blood substitutes and risk of myocardial infarction and death: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;299:2304–2312. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.19.jrv80007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Topaz O, Ebersole D, Das T, Alderman EL, Madyoon H, Vora K, et al. CARMEL multicenter trial. Excimer laser angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction (the CARMEL multicenter trial) Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:694–701. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dörr M, Vogelgesang D, Hummel A, Staudt A, Robinson DM, Felix SB, et al. Excimer laser thrombus elimination for prevention of distal embolization and no-reflow in patients with acute ST elevation myocardial infarction: Results from the randomized Laser AMI study. Int J Cardiol. 2007;116:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahm JB, Ebersole D, Das T, Madyhoon H, Vora K, Baker J, et al. Prevention of distal embolization and no-reflow in patients with acute myocardial infarction and total occlusion in the infarct-related vessel: A subgroup analysis of the cohort of acute revascularization in myocardial infarction with excimer laser-CARMEL multicenter study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;64:67–74. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tcheng JE, Wells LD, Phillips HR, Deckelbaum LI, Golobic RA. Development of a new technique for reducing pressure pulse generation during 308-nm excimer laser coronary angioplasty. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1995;34:15–22. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810340306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deckelbaum LI, Natarajan MK, Bittl JA, Rohlfs K, Scott J, Chisholm R, et al. Effect of intracoronary saline infusion on dissection during excimer laser coronary angioplasty: A randomized trial. The percutaneous excimer laser coronary angioplasty (PELCA) investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1264–1269. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prati F, Cera M, Ramazzotti V, Imola F, Giudice R, Giudice M, et al. From bench to bedside: A novel technique of acquiring OCT images. Circ J. 2008;72:839–843. doi: 10.1253/circj.72.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brezinski M, Saunders K, Jesser C, Li X, Fujimoto J. Index matching to improve optical coherence tomography imaging through blood. Circulation. 2001;103:1999–2003. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.15.1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertoluzzo SM, Bollini A, Rasia M, Raynal A. Kinetic model for erythrocyte aggregation. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 1999;25:339–349. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.1999.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen S, Gavish B, Zhang S, Mahler Y, Yedgar S. Monitoring of erythrocyte aggregate morphology under flow by computerized image analysis. Biorheology. 1995;32:487–496. doi: 10.1016/0006-355X(95)00025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu X, Wang RK, Elder JB, Tuchin VV. Effect of dextran-induced changes in refractive index and aggregation on optical properties of whole blood. Phys Med Biol. 2003;48:1205–1221. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/48/9/309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanigawa J, Barlis P, Di Mario C. Do unapposed stent struts endothelialise? In vivo demonstration with optical coherence tomography. Heart. 2007;93:378. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.091876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tearney GJ, Waxman S, Shishkov M, Vakoc BJ, Suter MJ, Freilich MI, et al. Three-dimensional coronary artery microscopy by intracoronary optical frequency domain imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol Imaging. 2008;1:752–761. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sones FM, Jr, Shirey EK. Cine coronary arteriography. Mod Concepts Cardiovasc Dis. 1962;31:735–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green GS, McKinnon CM, Rosch J, Judkins MP. Complications of selective percutaneous transfemoral coronary arteriography and their prevention. A review of 445 consecutive examinations. Circulation. 1972;45:552–557. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.45.3.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams DF, Fraser DB, Abrams HL. The complications of coronary arteriography. Circulation. 1973;48:609–618. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.48.3.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bourassa MG, Noble J. Complication rate of coronary arteriography. A review of 5250 cases studied by a percutaneous femoral technique. Circulation. 1976;53:106–114. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.53.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koppes GM. Complication rate of power coronary angiography injection. Angiology. 1980;31:130–135. doi: 10.1177/000331978003100208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ireland MA, Davis MJ, Hockings BE, Gibbons F. Safety and convenience of a mechanical injector pump for coronary angiography. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1989;16:199–201. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810160315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morise AP, Hardin NJ, Bovill EG, Gundel WD. Coronary artery dissection secondary to coronary arteriography: Presentation of three cases and review of the literature. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1981;7:283–296. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810070308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gardiner GA, Jr, Meyerovitz MF, Boxt LM, Harrington DP, Taus RH, Kandarpa K, et al. Selective coronary angiography using a power injector. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146:831–833. doi: 10.2214/ajr.146.4.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khoukaz S, Kern MJ, Bitar SR, Azrak E, Eisenhauer M, Wolford T, et al. Coronary angiography using 4 Fr catheters with acisted power injection: A randomized comparison to 6 Fr manual technique and early ambulation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2001;52:393–398. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brosh D, Assali A, Vaknin-Assa H, Fuchs S, Teplitsky I, Shor N, et al. The ACIST power injection system reduces the amount of contrast media delivered to the patient, as well as fluoroscopy time, during diagnostic and interventional cardiac procedures. Int J Cardiovasc Intervent. 2005;7:183–187. doi: 10.1080/14628840500390812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chahoud G, Khoukaz S, El-Shafei A, Azrak E, Bitar S, Kern MJ. Randomized comparison of coronary angiography using 4F catheters: 4F manual versus “Acisted” power injection technique. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2001;53:221–224. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anne G, Gruberg L, Huber A, Nikolsky E, Grenadier E, Boulus M, et al. Traditional versus automated injection contrast system in diagnostic and percutaneous coronary interventional procedures: Comparison of the contrast volume delivered. J Invasive Cardiol. 2004;16:360–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lehmann C, Hotaling M. Saving time, saving money: A time and motion study with contrast management systems. J Invasive Cardiol. 2005;17:118–121. quiz 122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jang IK, Bouma BE, Kang DH, Park SJ, Park SW, Seung KB, et al. Visualization of coronary atherosclerotic plaques in patients using optical coherence tomography: Comparison with intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:604–609. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01799-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yabushita H, Bouma BE, Houser SL, Aretz HT, Jang IK, Schlendorf KH, et al. Characterization of human atherosclerosis by optical coherence tomography. Circulation. 2002;106:1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000029927.92825.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamaguchi T, Terashima M, Akasaka T, Hayashi T, Mizuno K, Muramatsu T, et al. Safety and feasibility of an intravascular optical coherence tomography image wire system in the clinical setting. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:562–567. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.09.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Regar E, Prati F, Serruys PW. Intracoronary OCT application: Methodolical considerations. In: Regar E, van Leeuwen TG, Serruys PW, editors. Optical coherence tomography in cardiovascular research. 1st ed. London: Informa Healthcare; 2007. pp. 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kume T, Akasaka T, Kawamoto T, Watanabe N, Toyota E, Neishi Y, et al. Assessment of coronary intima—media thickness by optical coherence tomography: Comparison with intravascular ultrasound. Circ J. 2005;69:903–907. doi: 10.1253/circj.69.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsumoto D, Shite J, Shinke T, Otake H, Tanino Y, Ogasawara D, et al. Neointimal coverage of sirolimus-eluting stents at 6-month follow-up: Evaluated by optical coherence tomography. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:961–967. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guagliumi G, Sirbu V. Optical coherence tomography: High resolution intravascular imaging to evaluate vascular healing after coronary stenting. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;72:237–247. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pinto Slottow TL, Pakala R, Lovec RJ, Tio FO, Waksman R. Optical coherence tomographic imaging of a bioabsorbable magnesium stent lost in a porcine coronary artery. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2007;8:293–294. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pinto Slottow TL, Pakala R, Waksman R. Serial imaging and histology illustrating the degradation of a bioabsorbable magnesium stent in a porcine coronary artery. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:314. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ormiston JA, Serruys PW, Regar E, Dudek D, Thuesen L, Webster MW, et al. A bioabsorbable everolimus-eluting coronary stent system for patients with single de-novo coronary artery lesions (ABSORB): A prospective open-label trial. Lancet. 2008;371:899–907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kume T, Akasaka T, Kawamoto T, Ogasawara Y, Watanabe N, Toyota E, et al. Assessment of coronary arterial thrombus by optical coherence tomography. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1713–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kume T, Akasaka T, Yoshida K. Optical coherence tomography after cutting balloon angioplasty. Heart. 2007;93:546. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.091595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]