Abstract

All-trans-retinal, a retinoid metabolite naturally produced upon photoreceptor light activation, is cytotoxic when present at elevated levels in the retina. To lower its toxicity, two experimentally validated methods have been developed involving inhibition of the retinoid cycle and sequestration of excess of all-trans-retinal by drugs containing a primary amine group. We identified the first-in-class drug candidates that transiently sequester this metabolite or slow down its production by inhibiting regeneration of the visual chromophore, 11-cis-retinal. Two enzymes are critical for retinoid recycling in the eye. Lecithin:retinol acyltransferase (LRAT) is the enzyme that traps vitamin A (all-trans-retinol) from the circulation and photoreceptor cells to produce the esterified substrate for retinoid isomerase (RPE65), which converts all-trans-retinyl ester into 11-cis-retinol. Here we investigated retinylamine and its derivatives to assess their inhibitor/substrate specificities for RPE65 and LRAT, mechanisms of action, potency, retention in the eye, and protection against acute light-induced retinal degeneration in mice. We correlated levels of visual cycle inhibition with retinal protective effects and outlined chemical boundaries for LRAT substrates and RPE65 inhibitors to obtain critical insights into therapeutic properties needed for retinal preservation.

Introduction

Highly expressed in rod and cone photoreceptor cells of the retina, visual pigments are G protein–coupled receptors composed of an opsin apoprotein combined with a universal chromophore, 11-cis-retinal, through a protonated Schiff base (Palczewski et al., 2000; Palczewski, 2006). Upon absorption of a photon of light, the retinylidene chromophore is photoisomerized to an all-trans configuration with subsequent activation of the photoreceptor. Spontaneous hydrolysis of the Schiff base bond subsequently liberates all-trans-retinal from the opsin. Because visual pigments are densely packed at a local concentration up to 5 mM (Nickell et al., 2007), an intense stream of photons can result in high levels of all-trans-retinal. Even at low micromolar concentrations, this aldehyde is toxic (Maeda et al., 2008, 2009a; Chen et al., 2012) and primarily affects photoreceptor cells as demonstrated by novel imaging techniques (Maeda et al., 2014).

To restore photoreceptor sensitivity to light, a constant supply of 11-cis-retinal is required, and vertebrates use a metabolic pathway called the retinoid (visual) cycle, by which all-trans-retinal is enzymatically reisomerized back to the 11-cis configuration (Kiser et al., 2014). This process is facilitated by two nonredundant enzymes: lecithin:retinol acyltransferase (LRAT) and retinoid isomerase, a retinal pigmented epithelium-specific 65 kDa protein (RPE65) (Ruiz et al., 1999; Jin et al., 2005; Moiseyev et al., 2005) (Fig. 1). Retinylamine was the first described potent inhibitor of RPE65 (Golczak et al., 2005b). This retinoid is retained in the eye by the action of LRAT that produces its amidated precursors, and then the resulting retinyl amides are slowly hydrolyzed to evoke long-lasting suppression of retinoid isomerase activity (Golczak et al., 2005a). This mechanism revealed the possibility of targeting hydrophobic drugs to the eye and retaining them within the ocular tissue (Palczewski, 2010).

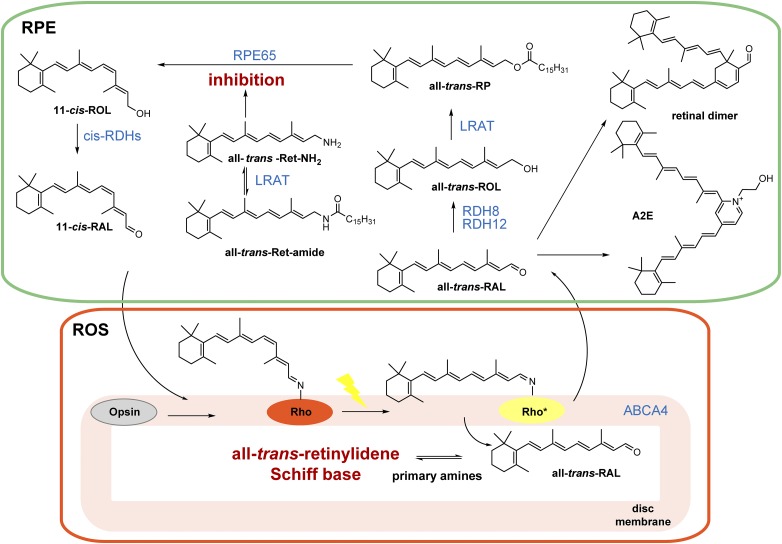

Fig. 1.

The retinoid (visual) cycle with therapeutic strategies against all-trans-retinal–mediated retinal degeneration. Photoisomerization of 11-cis-retinylidene bound to opsin results in release of all-trans-retinal from its protein opsin scaffold. All-trans-retinal is flipped by ABCA4 to the cytoplasmic leaflet of the disc lipid membrane and then reduced to all-trans-retinol by retinol dehydrogenase 8 (RDH8) and RDH11 in the RPE. Insufficient activity of these enzymes results in overaccumulation of all-trans-retinal and subsequent formation of precursors of N-retinylidene-N-retinylethanolamine (A2E) and retinal dimer. Importantly, all-trans-retinal itself is cytotoxic to photoreceptors. Formation of a transient Schiff base with primary amines can sequester the excess of this toxic aldehyde. Alternatively, cytoprotection can be achieved by inhibiting the visual cycle to slow down the supply of all-trans-retinal. all-trans-RAL, all-trans-retinal; all-trans-Ret, all-trans-retinylamine; all-trans-ROL, all-trans-retinol; all-trans-RP, all-trans-retinyl palmitate; 11-cis-RAL, 11-cis-retinal; 11-cis-ROL, 11-cis-retinol; ROS, rod outer segments.

An operative visual cycle is critical for sustaining continuous vision and maintaining the health of photoreceptor cells (Batten et al., 2004; Redmond et al., 2005). Proper homeostasis of retinoid metabolism supports visual function under a variety of lighting conditions. However, certain environmental insults including prolonged exposure to intense light in combination with an unfavorable genetic background can overcome the adaptive capabilities of the visual cycle and thus compromise retinal function (Travis et al., 2007; Maeda et al., 2008). A clinical example is Stargardt disease, an inherited form of juvenile macular degeneration that results in progressive vision loss associated with mutations in the photoreceptor-specific ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABCA4) that causes a delay in all-trans-retinal clearance (Azarian et al., 1998; Tsybovsky et al., 2010). The resulting increased concentrations of all-trans-retinal exert a direct cytotoxic effect on photoreceptors (Maeda et al., 2009b) in addition to contributing to formation of side products such as N-retinylidene-N-retinylethanolamine and retinal dimer (Parish et al., 1998; Mata et al., 2000; Fishkin et al., 2005).

Because retinylamine was highly protective against retinal degeneration in mice after short exposure to bright light, direct interaction and persistent suppression of RPE65 by retinylamine may not be the only protective mechanism involved (Maeda et al., 2008, 2009a, 2012). An alternative explanation is trapping the excess all-trans-retinal with primary amines (Maeda et al., 2012, 2014). Aldehyde-selective chemistry was used to reversibly conjugate all-trans-retinal with primary amine containing compounds structurally unrelated to retinylamine (Maeda et al., 2012). Several potential therapeutic compounds were identified that exhibited protective effects against retinal degeneration in animal models. However, potential improvements upon this approach could involve a search for molecules with extended half-lives in vivo, hijacking an eye-selective mechanism for their uptake and retention, and further lowering the concentration needed to achieve a therapeutic effect.

In this study, we investigated many derivatives of retinylamine to assess their substrate/inhibitor binding specificities for RPE65 and LRAT, the mechanism(s) of their action, potency, retention in the eye, and protection against acute light-induced retinal degeneration in mice. Such information could be critical for understanding the modes of action for current and future visual cycle modulators.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Synthesis.

Unless otherwise stated, solvents and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). QEA-A-002 and QEA-A-003 were obtained from Toronto Research Chemicals Inc. (Toronto, Canada). Other aldehydes were synthesized as described in the Supplemental Methods. Syntheses of primary alcohols and amines were performed by previously described procedures (Golczak et al., 2005a,b). 1H NMR spectra (300, 400, or 600 MHz) and 13C NMR spectra (100 or 150 MHz) were recorded with Varian Gemini and Varian Inova instruments (Varian, Palo Alto, CA).

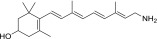

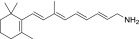

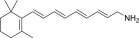

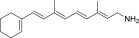

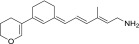

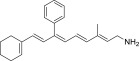

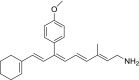

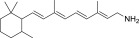

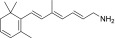

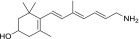

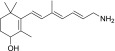

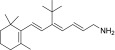

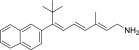

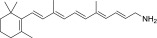

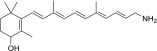

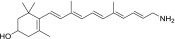

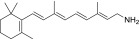

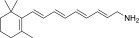

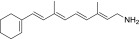

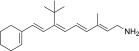

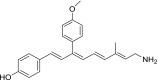

Because retinal is much more stable than retinylamine or retinol, all novel retinoid derivatives were synthesized and stored in their aldehyde forms, and then were converted to primary alcohols/amines just prior to compound screening. The general scheme of synthesis began with building the β-ionone ring analogs, and was followed by elongating the polyene chain with an aldol condensation, a Wittig-Horner reaction, or Suzuki coupling (Supplemental Methods). Synthesized retinal analogs were categorized as QEA, TEA, and PEA based on their polyene chain length (Fig. 2A). Among 35 synthesized aldehydes, four—QEA-E-001, QEA-E-002, QEA-F-001, and QEA-F-002—were unstable and decomposed before proper NMR spectra were completed. Structures and purities of all other compounds were confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR as well as by mass spectrometry (Supplemental Methods).

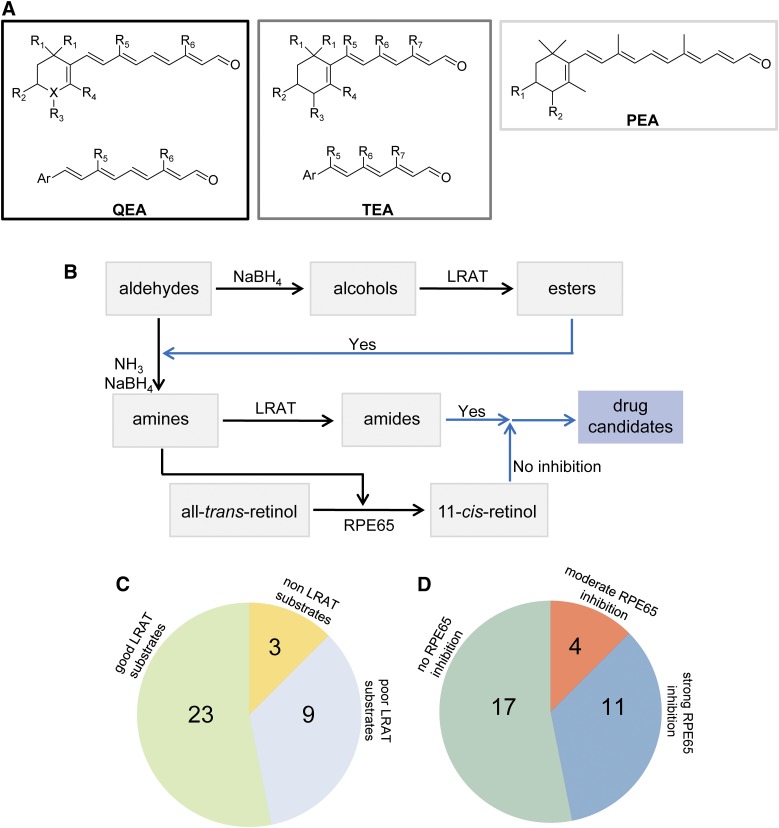

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of retinoid-based amines and their biologic activities. (A) Retinal analogs. For QEA, R1 and R4 represent H or methyl; R2 and R3 are H, hydroxyl; R5 is H, methyl, t-butyl, benzyl, or p-methoxy benzyl; R6 corresponds to H, methyl, or t-butyl; and X could be C, O, or N. When X is O, there is no R3 group. For QEA-D and QEA-G-001, R5 represents a -(CH2)3- bridge connecting C7 and C9. For TEA, R1 and R4 can be H or methyl, whereas R2 and R3 are H or hydroxyl; R5 is H or t-butyl; R6 can be H, methyl, t-butyl, or benzyl; and R7 corresponds to H or methyl. For PEA, R1 and R2 are H or hydroxyl. These compounds were converted to primary amines prior to the tests. (B) Schematic representation of the experimental design used to test the biologic activity of amines. The black arrows represent the chemical conversions of tested compounds, whereas blue arrows represent the candidate compound selection. (C) Fraction of tested compounds that serve as substrates of LRAT. (D) Extent of inhibition displayed by tested amines against RPE65 enzymatic activity.

Retinal Pigment Epithelium Microsomal Preparations.

Bovine retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) microsomes were isolated from RPE homogenates by differential centrifugation as previously described (Stecher and Palczewski, 2000). The resulting microsomal pellet was resuspended in 10 mM Bis-Tris propane/HCl buffer, pH 7.4, to achieve a total protein concentration of ∼5 mg·ml−1. Then the mixture was placed in a quartz cuvette and irradiated for 6 minutes at 4°C with a ChromatoUVE transilluminator (model TM-15; UVP, Upland, CA) to eliminate residual retinoids. After irradiation, dithiothreitol was added to the RPE microsomal mixture to achieve a final concentration of 5 mM.

LRAT Activity Assays.

Two microliters of a synthesized primary alcohol or amine dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF) (final concentration 10 µM) and 2 μl of 1,2-diheptanoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine (water, final concentration 1 mM) were added to 200 μl of 10 mM Bis-Tris propane/HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 μg of RPE microsomes and 1% (v/w) bovine serum albumin. The resulting mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. The reaction was quenched by adding 300 μl of methanol. Most reaction products were extracted with 300 μl of hexanes, except for products from the QEA-C-006 and QEA-G groups, which were extracted by adding 300 μl of ethyl acetate and 300 μl of water. Reaction products were separated and quantified by normal-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Agilent Sil, 5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) in a stepwise gradient of ethyl acetate in hexanes (0–15 minutes, 10%; 20–30 minutes, 30%) at a flow rate of 1.4 ml·min−1. Because both the substrate and product showed almost the same UV absorption maximum for each tested compound, quantification was based on equivalent UV absorption by the substrate and product at the absorbance maximum specific for a given compound.

Retinoid Isomerase Activity Assays.

Two microliters of the synthesized primary amine (in DMF, final concentration ranging between 1 and 100 µM) was added to 10 mM Bis-Tris propane/HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 μg of RPE microsomes, 1% bovine serum albumin, 1 mM disodium pyrophosphate, and 20 μM apo-retinaldehyde-binding protein 1. The resulting mixture was preincubated at room temperature for 5 minutes. Then 1 μl of all-trans-retinol (in DMF, final concentration 20 µM) was added. The resulting mixture was incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes to 2 hours. The reaction was quenched by adding 300 μl of methanol, and products were extracted with 300 μl of hexanes. Production of 11-cis-retinol was quantified by normal-phase HPLC with 10% (v/v) ethyl acetate in hexanes as the eluant at a flow rate of 1.4 ml·min−1. Retinoids were detected by monitoring their absorbance at 325 nm and quantified based on a standard curve representing the relationship between the amount of 11-cis-retinol and the area under the corresponding chromatographic peak.

Mouse Handling and Compound Administration.

Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− double knockout mice were generated as previously described (Maeda et al., 2008). Mice were housed in the Animal Resource Center at the School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, where they were maintained either in complete darkness or in a 12-hour light (∼300 lux)/12-hour dark cycle. All tested primary amines were suspended in 100 μl of soybean oil with less than 10% (v/v) dimethylsulfoxide and were administered by oral gavage with a 22-gauge feeding needle. Experimental manipulations in the dark were performed under dim red light transmitted through a Kodak No. 1 safelight filter (transmittance >560 nm) (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). All animal procedures and experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Case Western Reserve University and conformed to recommendations of the American Veterinary Medical Association Panel on Euthanasia and the Association of Research for Vision and Ophthalmology.

Induction of Acute Retinal Degeneration in Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− Mice.

After dark adaptation for 24 hours, 4-week-old male or female Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− mice with pupils dilated by 1% tropicamide were exposed to fluorescent light (10,000 lux, 150-W spiral lamp; Commercial Electric, Cleveland, OH) for 1 hour in a white paper bucket (PaperSmith, San Marcos, TX), and then kept in the dark for an additional 3 days. Development of retinal degeneration was then examined by ultra-high resolution spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) (Bioptigen, Morrisville, NC) and electroretinogram (ERG) as previously described (Maeda et al., 2009b; Zhang et al., 2013).

Analysis of Retinoid Composition in Mouse Tissues.

Two milligrams of primary amines were administered by oral gavage to 4-week-old Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− mice, which were then kept in the dark for 24 hours. Mice then were euthanized, and their livers were homogenized in 1 ml of 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 50% methanol (v/v). The resulting mixture was extracted with 4 ml of hexanes. Extracts were dried in vacuo, and reconstituted in 300 μl of hexanes. One hundred microliters of this solution was analyzed by HPLC as described earlier for the LRAT activity assay.

Visual Chromophore Recovery Assay.

After bright light exposure resulting in 90% photoactivation of rhodopsin, mice were kept in darkness for 2 hours to 7 days. Then animals were sacrificed and their eyes were collected and homogenized in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 50% methanol (v/v) and 40 mM hydroxylamine. The resulting mixture was extracted with 4 ml of hexanes. Extracts were dried in vacuo, reconstituted in 300 μl of hexanes, and 100 μl of extract was injected into an HPLC for analysis with 10% (v/v) ethyl acetate in hexanes.

Statistical Analyses.

Data representing the means ± S.D. for the results of at least three independent experiments were compared by the one-way analysis of variance Student’s t test. Differences with P values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Design and Synthesis of Novel Retinal Analogs.

To find primary amines that could serve as substrates of LRAT without imposing a strong inhibitory effect on retinoid isomerization, we designed and synthesized a series of retinoid analogs (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Methods). Prior to this study, the only known primary amine acting as a substrate for LRAT was retinylamine (Golczak et al., 2005a). Thus, retinylamine was chosen as a starting model for further chemical modifications. Although LRAT was shown to have a broad substrate specificity (Canada et al., 1990), chemical boundaries that determine the substrate selectivity for this enzyme had not been clarified. In contrast, the crystal structure of RPE65 was elucidated in detail (Kiser et al., 2009, 2012), revealing a narrow tunnel that leads into the active site of this enzyme. Indeed, a relatively small structural modification of the retinoid moiety could effectively abolish binding of an inhibitor to this enzyme. Thus, we hypothesized that a subset of primary amines and LRAT substrates would not inhibit RPE65 enzymatic activity.

In Vitro Screening to Identify the Boundary between Substrates of LRAT and RPE65 Inhibitors.

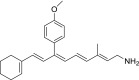

Properties of retinoid derivatives were examined with two standard enzymatic assays: the acylation by LRAT and retinoid isomerization by RPE65. To identify substrates of LRAT, aldehydes were first reduced by sodium borohydrate to their corresponding primary alcohols that then were used directly in the esterification assay (Fig. 2B). The alcohols were incubated with RPE microsomes that served as a source of LRAT enzymatic activity. Products of the enzymatic reaction as well as the remaining substrates were extracted with organic solvents and analyzed by HPLC. The ratio between a substrate and its esterified form was used to measure enzymatic activity, based on equivalent UV absorption of the substrate and product at their specific UV maximum wavelengths. Compounds classified as “good” LRAT substrates converted at least 50% of their available alcohol substrates into corresponding esters under these experimental conditions, whereas marginal LRAT substrates were converted at less than 5%. Alcohols with a 5–50% conversion ratio were classified as weak substrates. An example is shown in Fig. 3A for QEB-B-001. Among 35 tested compounds, 23 were categorized as good and nine as weak substrates; three compounds were not esterified by LRAT (Fig. 2C; Table 1). Based on these data, we conclude that the conformation of the β-ionone ring is a critical structural feature for LRAT substrate recognition. Importantly, various modifications within the β-ionone ring, including incorporation of heteroatoms, deletion of methyl groups, or addition of functional groups, did not significantly alter ester formation. Moreover, elongating double bond conjugation along the polyene chain or deletion of a C9 and/or a C13 methyl group also was allowed. In contrast, exchange of the C13 methyl with a bulky t-butyl group strongly inhibited substrate binding. Interestingly, the C9 methyl could be replaced with a variety of substituents, including a t-butyl, benzene, and its derivatives or even an alkyl chain bridging to C7, which resulted in a rigid configuration of the polyene chain. Reduced enzymatic activity was observed with ionylidene analogs of fewer than 12 carbons in length (Supplemental Table 1; Table 1).

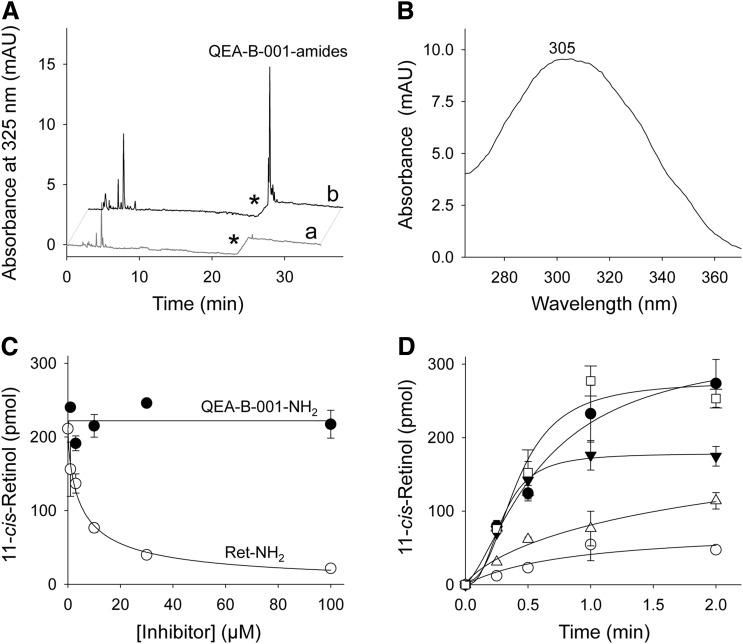

Fig. 3.

Amidation of QEA-B-001-NH2 and inhibition of RPE65. Primary amines were preincubated with bovine RPE microsomes at room temperature for 5 minutes; then all-trans-retinol was added and the mixture was incubated at 37°C. (A) HPLC chromatograph showing acylation of QEA-B-001-NH2 by LRAT in RPE microsomes; chromatograms “a” and “b” correspond to extracts of RPE microsomes in the absence and presence of QEA-B-001-NH2, respectively. Asterisks indicate a step change in the ethyl acetate mobile phase concentration (from 10 to 30% hexane). Under these chromatographic conditions, the free amine of QEA-B-001-NH2 did not elute from the normal-phase HPLC column without addition of ammonia to the mobile phase. (B) UV-Visible absorbance spectrum of a peak at 26 minutes of elution. This spectrum corresponds to QEA-B-001-NH2 amide. (C) Effect of inhibitor concentrations on the production of 11-cis-retinol. Inhibition of RPE65 enzymatic activity was measured as a decline in 11-cis-retinol production. ●, QEA-B-001-NH2; ○, retinylamine (Ret-NH2). All incubation mixtures were quenched by addition of methanol after 1 hour of incubation at room temperature. (D) 11-cis-Retinol production in the presence of 5 µM QEA-B-001-NH2 (●), 30 µM QEA-B-001-NH2 (▼), 5 µM Ret-NH2 (△), 30 µM retinylamine (○), and control (□).

TABLE 1.

Summary of primary amines as substrates for LRAT and RPE65 in vitro

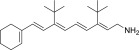

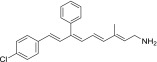

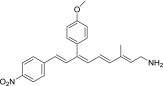

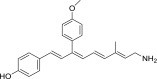

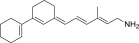

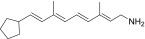

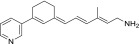

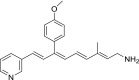

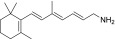

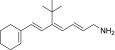

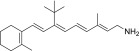

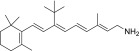

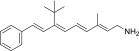

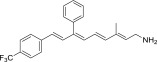

| Compound | Structure | LRAT Substratea | Inhibition of RPE65b |

|---|---|---|---|

| QEA-A-001-NH2 (retinyl amine) |  |

100% | Strong |

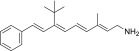

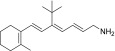

| QEA-A-002-NH2 |  |

100% | Strong |

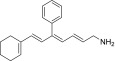

| QEA-A-003-NH2 |  |

100% | Strong |

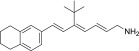

| QEA-A-004-NH2 |  |

100% | Strong |

| QEA-A-005-NH2 |  |

100% | Strong |

| QEA-A-006-NH2 |  |

100% | Moderate |

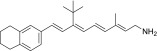

| QEA-B-001-NH2 |  |

80% | None |

| QEA-B-002-NH2 |  |

30% | None |

| QEA-B-003-NH2 |  |

100% | Moderate |

| QEA-B-004-NH2 |  |

0 | –c |

| QEA-B-005-NH2 |  |

0 | –c |

| QEA-C-001-NH2 |  |

50% | None |

| QEA-C-002-NH2 |  |

15% | None |

| QEA-C-003-NH2 |  |

100% | None |

| QEA-C-004-NH2 |  |

100% | None |

| QEA-C-005-NH2 |  |

100% | None |

| QEA-C-006-NH2 |  |

50% | None |

| QEA-D-001-NH2 |  |

100% | None |

| QEA-D-002-NH2 |  |

100% | None |

| QEA-E-001-NH2 |  |

100% | None |

| QEA-E-002-NH2 |  |

100% | None |

| QEA-F-001-NH2 |  |

–c | –c |

| QEA-F-002-NH2 |  |

–c | –c |

| QEA-G-001-NH2 |  |

100% | Moderate |

| QEA-G-002-NH2 |  |

100% | Moderate |

| TEA-A-001-NH2 |  |

100% | Strong |

| TEA-A-002-NH2 |  |

100% | Strong |

| TEA-A-003-NH2 |  |

90% | Strong |

| TEA-A-004-NH2 |  |

90% | Strong |

| TEA-B-001-NH2 |  |

100% | None |

| TEA-B-002-NH2 |  |

10% | None |

| TEA-B-003-NH2 |  |

20% | None |

| TEA-B-004-NH2 |  |

30% | None |

| TEA-C-001-NH2 |  |

0 | –c |

| TEA-C-002-NH2 |  |

20% | None |

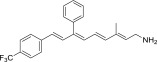

| PEA-A-001-NH2 |  |

100% | Strong |

| PEA-A-002-NH2 |  |

90% | Strong |

| PEA-A-003-NH2 |  |

90% | Strong |

LRAT substrates were assessed as percentages of their corresponding primary alcohols that were esterified by LRAT in 1 hour at 37°C.

“Strong” inhibition indicates that the IC50 of the tested amine was below 10 µM, “moderate” inhibition means that IC50 was between 10 and 100 µM, and “none” signifies that the IC50 was above 100 µM.

Not tested.

Primary amines of compounds derived from the aldehydes were subsequently tested for their ability to inhibit the RPE65-dependent retinoid isomerization reaction in a dose- and time-dependent manner, as exemplified by QEB-B-001 (Fig. 3B). Amines were incubated with RPE microsomes in the presence of all-trans-retinol and the 11-cis-retinoid binding protein, retinaldehyde-binding protein 1. Progress of the enzymatic reaction was monitored by HPLC separation of retinoids and quantification of 11-cis-retinol, with a decrease of 11-cis-retinol production reflecting inhibition of RPE65 by a tested amine. Compounds with an IC50 below 10 µM were defined as strong inhibitors, those with an IC50 between 10 and 100 µM were categorized as moderate inhibitors, and compounds with an IC50 above 100 µM were viewed as noninhibitors (Table 1). Among the 32 amines serving as substrates of LRAT, 11 exhibited strong inhibition of RPE65, four showed moderate inhibition, and 17 did not affect this isomerization reaction. Those amines exhibiting no inhibition had two common features: an altered β-ionone ring structure characterized by the absence of methyl groups and the presence of one bulky group such as a t-butyl or benzyl group at the C9 position. For example, QEA-B-001-NH2 was a good LRAT substrate but a modest or noninhibitor of RPE65 (Fig. 3). Compounds containing only one of these modifications (QEA-A-006-NH2 and QEA-B-003-NH2) showed moderate inhibition of RPE65, implying a synergistic effect of both changes in RPE65 inhibitory effect (Table 1). This moderate inhibition could be enhanced by shortening the polyene chain length (TEA amines) or diminished by introducing an extra positive charge into the tested compounds (QEA-G amines) (Supplemental Table 1).

Protective Effects of Primary Amines against Light-Induced Retinal Degeneration.

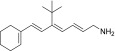

Our in vitro screening identified 17 candidates which could be acylated by LRAT and yet did not inhibit RPE65. For practical reasons, only eight of these lead compounds (QEA-B-001-NH2, QEA-B-002-NH2, QEA-C-001-NH2, QEA-C-003-NH2, QEA-C006-NH2, QEA-E-002-NH2, TEA-B-002-NH2, and TEA-C00-2-NH2) along with retinylamine as a control were selected for further testing in Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− mice, an animal model for light-induced retinal degeneration (Maeda et al., 2008) (Table 2). Additionally, two novel amines with moderate inhibition of RPE65 (QEA-A-006-NH2 and QEA-B-003-NH2) and one with strong inhibition (QEA-A-005-NH2) were added to the first test group for comparison. Mice were treated by oral gavage with 2 mg of a test compound and then kept in the dark for 24 hours prior to being exposed to bright light (∼10,000 lux) for 1 hour (Maeda et al., 2012). Retinal damage was assessed with OCT by measuring the thickness of the outer nuclear layer and by determining 11-cis-retinal levels in the eye (Fig. 4). Additionally, extracts of livers obtained from treated mice were analyzed by HPLC to estimate the amounts of corresponding amides (Fig. 4D).

TABLE 2.

Protective effects of primary amines against intense light-induced retinal degeneration in 4-week-old Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− mice

Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− mice treated with tested amines were kept in the dark for 24 hours, and then bleached with 10,000 lux light for 1 hour as described in the Materials and Methods section.

| Compound | Structure | Ocular Protection | Amide Formation in Liver | Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QEA-A-001-NH2 (retinylamine) |  |

Yes | Strong | None |

| QEA-A-005-NH2 |  |

Yes | Strong | None |

| QEA-A-006-NH2 |  |

None | None | None |

| QEA-B-001-NH2 |  |

None | Strong | Yes |

| QEA-B-002-NH2 |  |

None | None | None |

| QEA-B-003-NH2 |  |

None | Weak | None |

| QEA-C-001-NH2 |  |

None | Strong | Yes |

| QEA-C-003-NH2 |  |

None | None | Yes |

| QEA-C-006-NH2 |  |

None | None | None |

| QEA-E-002-NH2 |  |

Weak | Weak | None |

| TEA-B-002-NH2 |  |

None | None | Yes |

| TEA-C-002-NH2 |  |

None | Strong | Yes |

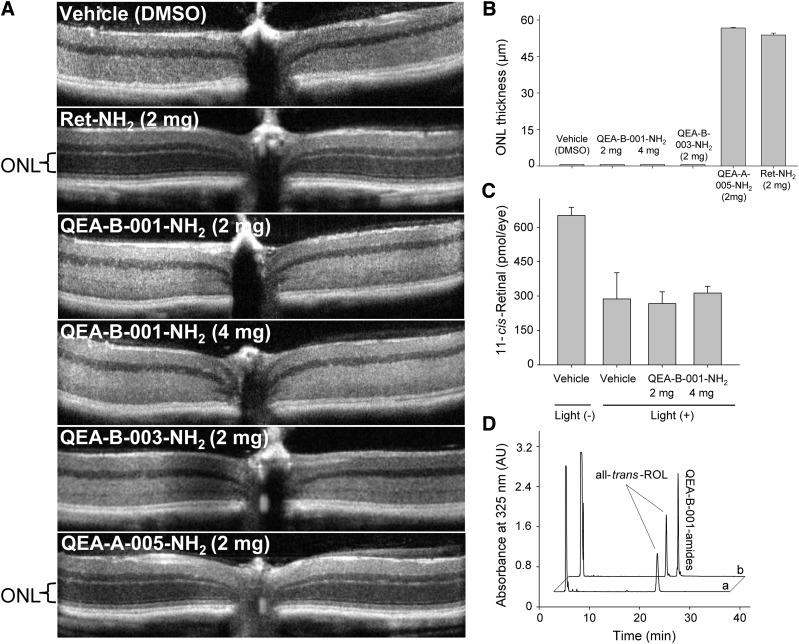

Fig. 4.

Protective effects of selected amines against light-induced retinal degeneration. Four-week-old Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− mice treated with tested amine compounds were kept in the dark for 24 hours and then bleached with 10,000 lux light for 1 hour. (A) Representative OCT images of retinas from mice treated by oral gavage with 2 or 4 mg of different amines. (B) Quantification of the protective effects of QEA-B-001-NH2, QEA-B-003-NH2, QEA-A-005-NH2, and retinylamine (Ret-NH2) is shown by measuring the averaged thickness of the ONL. A dramatic decrease in ONL thickness indicates advanced retinal degeneration. Ret-NH2 (2 mg) and QEA-A-005-NH2 (4 mg) protected the ONLs of these mice. (C) Quantification of 11-cis-retinal in the eyes of mice kept in dark for 7 days after bleaching. The decreased amount of 11-cis-retinal in damaged eyes reflects the loss of photoreceptors. (D) HPLC chromatograph showing acylation of QEA-B-001-NH2 in mouse liver; “a” is a representative chromatogram of a liver extract from mice treated with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, vehicle) only, whereas “b” corresponds to an extract from mice treated with 2 mg of QEA-B-001-NH2.

Among tested compounds, only inhibitors of RPE65, including QEA-A-005-NH2 and retinylamine, provided significant protection against light-induced retinal degeneration (Table 2). Remaining compounds characterized as weak inhibitors did not prevent retinal deterioration. One possible explanation is that instability of these compounds in vivo caused their failure to protect. Despite being substrates for LRAT, seven compounds (QEA-A-006-NH2, QEA-B-002-NH2, QEA-B-003-NH2, QEA-C-003-NH2, QEA-C-006-NH2, QEA-E-002-NH2, and TEA-B-002-NH2) were not efficiently amidated in vivo, as shown by a lack of accumulation of their amide forms in mouse liver. Whether these compounds were removed from the biologic system before or after amidation by LRAT is not clear. Nonetheless, inadequate levels of primary amines in vivo would have resulted from either scenario. Thus, it was not surprising to observe retinal degeneration in OCT images of mice treated with these amines (Fig. 4, A and B). In contrast, compounds QEA-B-001-NH2, QEA-C-001-NH2, and TEA-C-002-NH2, which did not inhibit RPE65, were efficiently converted into amides in vivo, as was apparent from their intense amide peaks present in liver. Notably, none of these compounds protected against retinal degeneration either. Levels of 11-cis-retinal quantified 3 days after light exposure indicated that only 50% of photoreceptors remained as compared with those in control healthy mice (Fig. 4C). The relatively high levels of residual 11-cis-retinal in examined samples may indicate that the disorganization of the outer nuclear layer (ONL) seen in OCT images did not reflect the death of all photoreceptor cells. Additionally, rod outer segments of the compromised photoreceptors loaded with rhodopsin could persist in the retina for some time before they are cleared. Although QEA-B-001-NH2 was stored as amides in the liver, its inability to prevent light-induced retinal degeneration could be attributed to an insufficient concentration of free amine in eyes needed to sequester the excess all-trans-retinal produced by photobleaching.

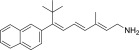

Functional Relationship between Inhibition of the Visual Cycle and Retinal Protection.

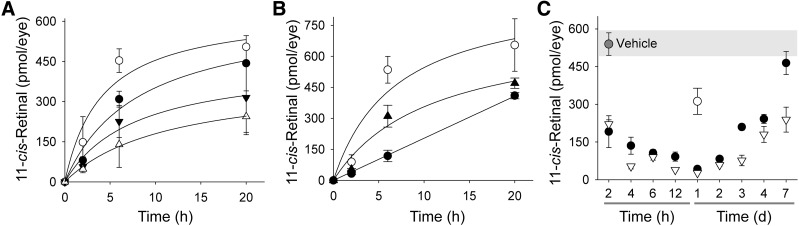

As indicated earlier, inhibition of RPE65 can protect the retina against light-induced damage. However, a fundamental question is to what extent RPE65 enzymatic activity needs to be affected to achieve this therapeutic effect. To answer this question, we measured the rate of the visual chromophore recovery in wild-type mice pretreated with retinylamine and exposed to light illumination that activated ∼90% of rhodopsin yet failed to trigger retinal degeneration. As demonstrated in Fig. 5A, mice without treatment had recovered ∼85 ± 5% of the prebleached 11-cis-retinal level in the eye at 6 hours, whereas mice exposed to light 2 hours after administration of 0.2 mg of retinylamine recovered only 50 ± 13%. Importantly, animals treated with the same amount of retinylamine but exposed to light 24 hours later exhibited a much slower recovery of 11-cis-retinal in the eye—namely, only 22 ± 5.0% of the prebleached level (Fig. 5B). When the retinylamine inhibitory effect was investigated over a broader time period (Fig. 5C), 24 hours postadministration was found to be the time point with the strongest inhibition, regardless of a 5-fold difference in the retinylamine dose. The inhibitory effect observed for the 0.2-mg dose decreased by day 3, resulting in 61 ± 2.2% of recovered 11-cis-retinal, and nearly disappeared by day 7. In contrast, 0.5 mg of retinylamine still strongly affected the rate of 11-cis-retinal regeneration at day 7, allowing only a partial recovery (56 ± 9.1%).

Fig. 5.

Inhibitory effects of retinylamine on the visual cycle in vivo. Inhibition of the retinoid cycle was measured by recovery of 11-cis-retinal in the eyes of wild-type mice after exposure to bright light. Recovery of 11-cis-retinal in the eyes of mice when retinylamine was administered 2 hours (A) or 24 hours (B) prior to light exposure (○, control; ●, 0.2 mg retinylamine; ▾, 0.5 mg retinylamine; ∆, 1.0 mg retinylamine; ▴, 0.5 mg retinylamine). Mice treated with vehicle only achieved over 80% of 11-cis-retinal recovery by 6 hours after bleaching. (C) Temporal profile of the retinylamine effect on the retinoid cycle. Mice were treated by oral gavage with retinylamine 2 hours to 7 days before light exposure. Amounts of 11-cis-retinal in the eye were measured 6 hours after bleaching. Inhibition achieved a maximum at 24 hours after bleaching and lasted more than 7 days. Symbols represent doses of retinylamine (○, 0.1 mg; ●, 0.2 mg; ∆, 0.5 mg). Since inhibition of the visual cycle at the 0.1-mg dose did not offer sufficient protection against retinal degeneration, it could be considered as a reference point for higher doses. Thus, we decided to collect data only for a time point at which the inhibitory effect was the most profound. The slow decrease of the inhibitory effect after day 2 reflects delayed clearance of retinylamine or retinylamide from the RPE.

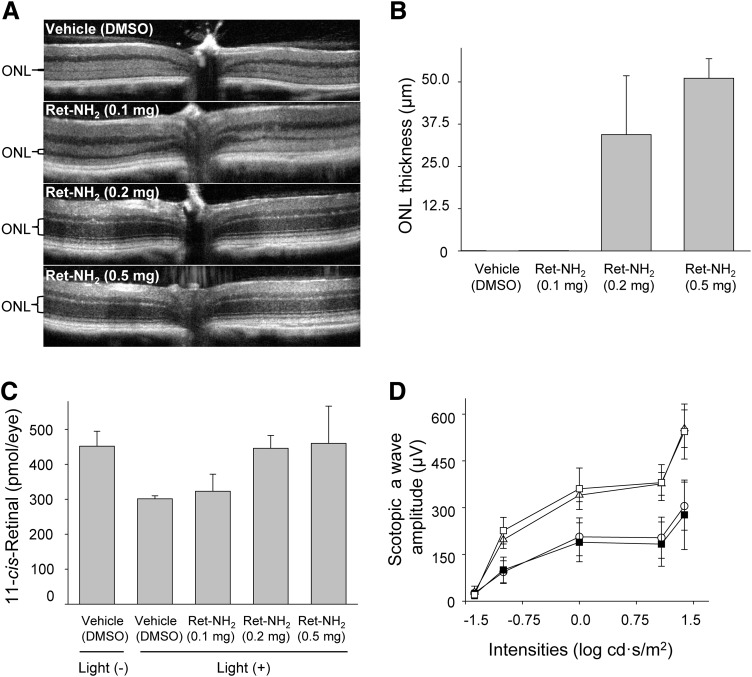

Once the time course of retinylamine’s inhibitory effect was established, we investigated the correlation between the level of inhibition and the protective effect on the retina. Four-week-old Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− mice were treated by oral gavage with 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 mg of retinylamine, respectively, and kept in the dark for 24 hours. Mice then were bleached with 10,000 lux bright light for 1 hour. Measured as described earlier, the recovery of visual chromophore was inhibited by about 40, 80, and 95%, respectively, by these tested doses (Fig. 5, B and C). Bleached mice were kept in the dark for 3 days, and then imaged by OCT (Fig. 6, A and B). Mice treated with only 0.1 mg of retinylamine developed severe retinal degeneration, similar to that observed in mice without treatment, whereas mice treated with 0.5 mg of retinylamine showed a clear intact ONL image. The average ONL thickness in the latter group was 51.1 ± 5.8 µm, well within the range of healthy retinas. Concurrently, OCT imaging revealed that mice treated with the 0.2-mg dose were partially protected. Their average ONL thickness was 34.4 ± 17.4 µm. In an equivalent experiment, mice were kept in the dark for 7 days prior to quantification of visual chromophore levels. Mice treated with 0.2 mg of retinylamine showed the same 11-cis-retinal levels (445 ± 37 pmol/eye) as control mice not exposed to light (452 ± 43 pmol/eye), whereas mice treated by oral gavage with a 0.1-mg dose and untreated animals had 323 ± 48 and 301 ± 8 pmol/eye, respectively, suggesting damage to the retina (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, mice treated with the 0.2- and 0.5-mg doses of retinylamine showed the same ERG scotopic a-wave responses, whereas animals provided with 0.1 mg of the compound revealed attenuated ERG responses similar to those of untreated controls (Fig. 6D). Thus, the 0.1-mg dose failed to protect against retinal degeneration under the bright light exposure conditions described in this study.

Fig. 6.

Protective effects of retinylamine against light-induced retinal degeneration. Mice treated by oral gavage with different doses of retinylamine were kept in the dark for 24 hours and then bleached with 10,000 lux light for 1 hour. (A) Representative OCT images of mouse retinas 3 days after bleaching. (B) Quantification of ONL thickness by OCT. (C) Recovery of 11-cis-retinal in retinas of mice kept in the dark for 7 days after bleaching. The decreased amounts of 11-cis-retinal in the damaged eyes reflect the loss of photoreceptors. (D) Representative scotopic ERG responses of mice kept in the dark for 7 days after bleaching. ○, 0.1 mg; Δ, 0.2 mg; □, 0.5 mg; ▪, vehicle [dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)].

Discussion

Development of safe and effective small-molecule therapeutics for blinding retinal degenerative diseases still remains a major challenge. Ophthalmic drugs comprise a special category of therapeutics. Their site of action is limited to a relatively small organ protected by both static and dynamic barriers, including different layers of the cornea, sclera, and retina and blood-retinal barriers, in addition to choroidal blood flow, lymphatic clearance, and dilution by tears (Gaudana et al., 2010). Thus, designing efficient drug delivery systems, especially those directed to the posterior segment of the eye, has been a major problem. This challenge certainly applies to therapeutics administered systemically. Oral delivery is definitely the most feasible noninvasive and patient-preferred route for treating chronic retinal diseases. But inadequate accessibility of targeted ocular tissues after oral administration often requires high drug doses that cause unwanted systemic side effects. Examples are acetazolamide and ethoxzolamide, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, and antiglaucoma drugs that have been discontinued due to their systemic toxicity (Kaur et al., 2002; Shirasaki, 2008).

Recently, the first-in-class drug candidates were discovered that transiently sequester the toxic all-trans-retinal metabolite produced in excess under adverse conditions. These compounds do not inhibit enzymes, channels, or receptors, but instead react with all-trans-retinal to form a Schiff base and thus reduce peak concentrations of this potentially toxic aldehyde. Because this reaction is readily reversible, there is no discernable diminution in the total amount of all-trans-retinal needed to replenish the visual chromophore. Present at high micromolar levels, all-trans-retinal is uniquely concentrated in the eye and constitutes an ideal target for primary amine-containing drugs that do not interact with cellular machinery and processes. But to be an effective drug, the primary amine also must be delivered to and be retained in the eye. Primary amines can be amidated with fatty acids by LRAT and retained in the eye, but then the similar substrate/product profile shown by another key enzyme of the retinoid cycle, RPE65, can produce the undesirable side effect of severely delayed dark adaptation. In this study, we performed enzymatic tests that delineated the chemical boundaries for LRAT substrate and RPE65 inhibitor specificities. Next, we tested the role of LRAT enzymatic activity in ocular tissue uptake and in establishing an equilibrium between primary amines and their acylated forms together with their retention in vivo. A similar protocol was used to assess the inhibition of RPE65 and corresponding levels of visual chromophore production and the duration of their suppression. Finally, we used the Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− mouse model of Stargardt disease to assess the ocular tissue uptake and mechanism of action of several retinoid-derived amines in vivo. These new compounds were examined for their therapeutic protection against bright light–induced retinal damage. This extensive search has yielded a new class of compounds for the treatment of retinal degeneration.

Extensive studies on animals, including rats as well as wild-type and Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− double knockout mice that closely mimic many features of human retinal degeneration, have shown that retinylamine exhibits a protective effect against light-induced damage by preventing the buildup of all-trans-retinal and its condensation products (Golczak et al., 2005b, 2008; Maeda et al., 2008; Berkowitz et al., 2009). However, prolonged complete inhibition of 11-cis-retinoid production would cause accumulation of unliganded opsin, a condition that resembles Leber congenital amaurosis and leads to retinal dystrophies. Thus, a partial slowing but not a complete blockage of visual chromophore regeneration offers an optimal therapeutic window for prevention of many degenerative retinal diseases.

Many drug side effects could be minimized by improving tissue-specific drug uptake through the use of existing nutrient transport systems. Visual functions of the eye, unlike any other tissue, depend on vitamin A. In fact, retinoids are preferentially taken up by the eye at the expense of other peripheral tissues (Amengual et al., 2012). This selectivity offers the opportunity of designing compounds that use vitamin A transport machinery and thus benefit from efficient and active uptake into the eye, low systemic toxicity, and dramatically improved pharmacokinetics (Moise et al., 2007). Retinylamine well illustrates this concept. This inhibitor of RPE65 has a reactive amine group instead of an alcohol, yet similar to vitamin A, it can also be acylated and stored in the form of a corresponding fatty acid amide. Solely responsible for catalyzing amide formation, LRAT is a critical enzyme in determining cellular uptake (Batten et al., 2004; Golczak et al., 2005a). Conversion of retinylamine to pharmacologically inactive retinylamides occurs in the liver and RPE, leading to safe storage of this inhibitor as a prodrug within these tissues (Maeda et al., 2006). Retinylamides are then slowly hydrolyzed back to free retinylamine, providing a steady supply and prolonged therapeutic effect for this active retinoid with lowered toxicity.

To investigate whether the vitamin A–specific absorption pathway can be used by drugs directed at protecting the retina, we examined the substrate specificity of the key enzymatic component of this system, LRAT. Over 35 retinoid derivatives were tested that featured a broad range of chemical modifications within the β-ionone ring and polyene chain (Supplemental Table 1; Table 1). Numerous modifications of the retinoid moiety, including replacements within the β-ionone ring, elongation of the double-bound conjugation, as well as substitution of the C9 methyl with a variety of substituents including bulky groups, did not abolish acylation by LRAT, thereby demonstrating a broad substrate specificity for this enzyme. These findings are in a good agreement with the proposed molecular mechanism of catalysis and substrate recognition based on the crystal structures of LRAT chimeric enzymes (Golczak et al., 2005b, 2015). Thus, defining the chemical boundaries for LRAT-dependent drug uptake offers an opportunity to improve the pharmacokinetic properties of small molecules targeted against the most devastating retinal degenerative diseases. This approach may help establish treatments not only for ocular diseases but also other pathologies such as cancer in which retinoid-based drugs are used.

Two experimentally validated methods for prevention of light-induced retinal degeneration involve 1) sequestration of excess of all-trans-retinal by drugs containing a primary amine group, and 2) inhibition of the retinoid cycle (Maeda et al., 2008, 2012). The unquestionable advantage of the first approach is the lack of adverse side effects caused by simply lowering the toxic levels of free all-trans-retinal. LRAT substrates persist in tissue in two forms: free amines and their acylated (amide) forms. The equilibrium between an active drug and its prodrug is determined by the efficiency of acylation and breakdown of the corresponding amide. Our data suggest that compounds that were fair LRAT substrates but did not inhibit RPE65 were efficiently delivered to ocular tissue. However, their free amine concentrations were too low to effectively sequester the excess of free all-trans-retinal and thus failed to protect against retinal degeneration. In contrast, potent inhibitors of RPE65 that were acylated by LRAT revealed excellent therapeutic properties. Therefore, it became clear that LRAT-aided tissue-specific uptake of drugs is therapeutically beneficial only for inhibitors of the visual cycle.

The ultimate result of our experiments was a determination of key structural features of RPE65 inhibitors that determine their function. The narrow hydrophobic tunnel leading to the active site of RPE65 explains why introduction of a bulky group such as a t-butyl or benzyl at the C9 position should weaken the inhibitory effect. However, it was surprising to find that methyl groups on the β-ionone ring contributed significantly to inhibitory binding (QEA-A-006-NH2). In contrast, the conformation of the β-ionone ring had only a slight impact (TEA-A-002-NH2). Interestingly, introduction of an extra nitrogen atom (QEA-G-001-NH2 and QEA-G-002-NH2) moderately recovered the inhibitory properties. This observation supports the previous hypothesis that the isomerization occurs via a carbocation intermediate, and that the positively charged compound inhibits the reaction (Golczak et al., 2005b; Kiser et al., 2009, 2012, 2014).

Finding effective treatments for ocular degenerative diseases is an ongoing task. Challenges in designing the most effective drugs are not limited to optimization of drug-target interactions but also involve understanding routes of eye-specific drug absorbance and storage. We believe that investigating the specificity of natural eye delivery systems and the mode of action of primary amines will shed new light on the prospects and limitations associated with the development of novel small-molecule ocular therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Leslie T. Webster Jr., and members of the Palczewski laboratory for helpful comments on this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- ERG

electroretinography

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- LRAT

lecithin:retinol acyltransferase

- OCT

optical coherence tomography

- ONL

outer nuclear layer

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

- RPE65

retinoid isomerase

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Zhang, Golczak, Palczewski, Seibel, Papoian.

Conducted experiments: Zhang, Dong, Golczak.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Zhang, Dong, Mundla, Hu, Seibel, Papoian.

Performed data analysis: Zhang, Dong, Palczewski, Golczak.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Zhang, Palczewski, Golczak.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grants R01-EY009339 and R24-EY021126 to K.P. and R01-EY023948 to M.G.] and the Foundation Fighting Blindness [K.P.]. K.P. is John H. Hord Professor of Pharmacology.

K.P. and M.G. are inventors of U.S. Patent No. 8722669, “Compounds and Methods of Treating Ocular Disorders,” and U.S. Patent No. 20080275134, “Methods for Treatment of Retinal Degenerative Disease,” issued to Case Western Reserve University (CWRU), whose values may be affected by this publication. CWRU may license this technology for commercial development. K.P. is a member of the scientific board of Vision Medicine, Inc., involved in developing visual cycle modulators, and their values may be affected by this publication.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Amengual J, Golczak M, Palczewski K, von Lintig J. (2012) Lecithin:retinol acyltransferase is critical for cellular uptake of vitamin A from serum retinol-binding protein. J Biol Chem 287:24216–24227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azarian SM, Megarity CF, Weng J, Horvath DH, Travis GH. (1998) The human photoreceptor rim protein gene (ABCR): genomic structure and primer set information for mutation analysis. Hum Genet 102:699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batten ML, Imanishi Y, Maeda T, Tu DC, Moise AR, Bronson D, Possin D, Van Gelder RN, Baehr W, Palczewski K. (2004) Lecithin-retinol acyltransferase is essential for accumulation of all-trans-retinyl esters in the eye and in the liver. J Biol Chem 279:10422–10432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz BA, Roberts R, Oleske DA, Chang M, Schafer S, Bissig D, Gradianu M. (2009) Quantitative mapping of ion channel regulation by visual cycle activity in rodent photoreceptors in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50:1880–1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cañada FJ, Law WC, Rando RR, Yamamoto T, Derguini F, Nakanishi K. (1990) Substrate specificities and mechanism in the enzymatic processing of vitamin A into 11-cis-retinol. Biochemistry 29:9690–9697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Okano K, Maeda T, Chauhan V, Golczak M, Maeda A, Palczewski K. (2012) Mechanism of all-trans-retinal toxicity with implications for stargardt disease and age-related macular degeneration. J Biol Chem 287:5059–5069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishkin NE, Sparrow JR, Allikmets R, Nakanishi K. (2005) Isolation and characterization of a retinal pigment epithelial cell fluorophore: an all-trans-retinal dimer conjugate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:7091–7096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudana R, Ananthula HK, Parenky A, Mitra AK. (2010) Ocular drug delivery. AAPS J 12:348–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golczak M, Imanishi Y, Kuksa V, Maeda T, Kubota R, Palczewski K. (2005a) Lecithin:retinol acyltransferase is responsible for amidation of retinylamine, a potent inhibitor of the retinoid cycle. J Biol Chem 280:42263–42273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golczak M, Kuksa V, Maeda T, Moise AR, Palczewski K. (2005b) Positively charged retinoids are potent and selective inhibitors of the trans-cis isomerization in the retinoid (visual) cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:8162–8167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golczak M, Maeda A, Bereta G, Maeda T, Kiser PD, Hunzelmann S, von Lintig J, Blaner WS, Palczewski K. (2008) Metabolic basis of visual cycle inhibition by retinoid and nonretinoid compounds in the vertebrate retina. J Biol Chem 283:9543–9554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golczak M, Sears AE, Kiser PD, Palczewski K. (2015) LRAT-specific domain facilitates vitamin A metabolism by domain swapping in HRASLS3. Nat Chem Biol 11:26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M, Li S, Moghrabi WN, Sun H, Travis GH. (2005) Rpe65 is the retinoid isomerase in bovine retinal pigment epithelium. Cell 122:449–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur IP, Smitha R, Aggarwal D, Kapil M. (2002) Acetazolamide: future perspective in topical glaucoma therapeutics. Int J Pharm 248:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiser PD, Farquhar ER, Shi W, Sui X, Chance MR, Palczewski K. (2012) Structure of RPE65 isomerase in a lipidic matrix reveals roles for phospholipids and iron in catalysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:E2747–E2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiser PD, Golczak M, Lodowski DT, Chance MR, Palczewski K. (2009) Crystal structure of native RPE65, the retinoid isomerase of the visual cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:17325–17330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiser PD, Golczak M, Palczewski K. (2014) Chemistry of the retinoid (visual) cycle. Chem Rev 114:194–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda A, Golczak M, Chen Y, Okano K, Kohno H, Shiose S, Ishikawa K, Harte W, Palczewska G, Maeda T, et al. (2012) Primary amines protect against retinal degeneration in mouse models of retinopathies. Nat Chem Biol 8:170–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda A, Maeda T, Golczak M, Chou S, Desai A, Hoppel CL, Matsuyama S, Palczewski K. (2009a) Involvement of all-trans-retinal in acute light-induced retinopathy of mice. J Biol Chem 284:15173–15183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda A, Maeda T, Golczak M, Imanishi Y, Leahy P, Kubota R, Palczewski K. (2006) Effects of potent inhibitors of the retinoid cycle on visual function and photoreceptor protection from light damage in mice. Mol Pharmacol 70:1220–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda A, Maeda T, Golczak M, Palczewski K. (2008) Retinopathy in mice induced by disrupted all-trans-retinal clearance. J Biol Chem 283:26684–26693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T, Maeda A, Matosky M, Okano K, Roos S, Tang J, Palczewski K. (2009b) Evaluation of potential therapies for a mouse model of human age-related macular degeneration caused by delayed all-trans-retinal clearance. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50:4917–4925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda A, Palczewska G, Golczak M, Kohno H, Dong Z, Maeda T, Palczewski K. (2014) Two-photon microscopy reveals early rod photoreceptor cell damage in light-exposed mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:E1428–E1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata NL, Weng J, Travis GH. (2000) Biosynthesis of a major lipofuscin fluorophore in mice and humans with ABCR-mediated retinal and macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:7154–7159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moise AR, Noy N, Palczewski K, Blaner WS. (2007) Delivery of retinoid-based therapies to target tissues. Biochemistry 46:4449–4458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moiseyev G, Chen Y, Takahashi Y, Wu BX, Ma JX. (2005) RPE65 is the isomerohydrolase in the retinoid visual cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:12413–12418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickell S, Park PS, Baumeister W, Palczewski K. (2007) Three-dimensional architecture of murine rod outer segments determined by cryoelectron tomography. J Cell Biol 177:917–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palczewski K. (2006) G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin. Annu Rev Biochem 75:743–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palczewski K. (2010) Retinoids for treatment of retinal diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci 31:284–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, Fox BA, Le Trong I, Teller DC, Okada T, Stenkamp RE, et al. (2000) Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science 289:739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish CA, Hashimoto M, Nakanishi K, Dillon J, Sparrow J. (1998) Isolation and one-step preparation of A2E and iso-A2E, fluorophores from human retinal pigment epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:14609–14613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond TM, Poliakov E, Yu S, Tsai JY, Lu Z, Gentleman S. (2005) Mutation of key residues of RPE65 abolishes its enzymatic role as isomerohydrolase in the visual cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:13658–13663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz A, Winston A, Lim YH, Gilbert BA, Rando RR, Bok D. (1999) Molecular and biochemical characterization of lecithin retinol acyltransferase. J Biol Chem 274:3834–3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasaki Y. (2008) Molecular design for enhancement of ocular penetration. J Pharm Sci 97:2462–2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher H, Palczewski K. (2000) Multienzyme analysis of visual cycle. Methods Enzymol 316:330–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis GH, Golczak M, Moise AR, Palczewski K. (2007) Diseases caused by defects in the visual cycle: retinoids as potential therapeutic agents. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 47:469–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsybovsky Y, Molday RS, Palczewski K. (2010) The ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCA4: structural and functional properties and role in retinal disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 703:105–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Kolesnikov AV, Jastrzebska B, Mustafi D, Sawada O, Maeda T, Genoud C, Engel A, Kefalov VJ, Palczewski K. (2013) Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa E150K opsin mice exhibit photoreceptor disorganization. J Clin Invest 123:121–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.