Abstract

Whether perceived or enacted, HIV-related stigma is widespread in India, and has had a crippling effect on People Living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA). Research has shown that a positive attitude towards the illness sets a proactive framework for the individual to cope with his or her infection; therefore, healthy coping mechanisms are essential to combat HIV-related stigma. This qualitative study involving in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with PLHA affiliated with HIV support groups in South India explored positive coping strategies employed by PLHA to deal with HIV-related stigma. Interviews and focus group discussions were translated, transcribed, and analyzed for consistent themes. Taboos surrounding modes of transmission, perceiving sex workers as responsible for the spread of HIV, and avoiding associating with PLHA provided the context of HIV-related stigma. Despite these challenges, PLHA used several positive strategies, classified as Clear Knowledge and Understanding of HIV, Social Support and Family Well-Being, Selective Disclosure, Employment Building Confidence, and Participation in Positive Networks. Poor understanding of HIV and fears of being labeled immoral undermined healthy coping behavior, while improved understanding, affiliation with support groups, family support, presence of children, and financial independence enhanced PLHA confidence. Such positive coping behaviours could inform culturally relevant interventions.

Introduction

Adiagnosis of HIV/AIDS carries significant physical and psychological implications. In addition to the effect of HIV on physical health, People Living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA) commonly experience depression, fear, anxiety, anger, worry, and feelings of isolation.1–3 Many feel deeply stigmatized. This often motivates them to isolate themselves and avoid proactive behaviors that might improve their quality of life.4,5 To counteract this, effective coping mechanisms to deal with the disease, and the stigma associated with it, are essential.

In India, the stigma surrounding HIV /AIDS is compounded by the belief that the disease afflicts those already marginalized by societies, who are seen as being “perverted” and “sinful”.6 The implications of this are highlighted in one study7 that found that the fear of being stigmatized among a sample of PLHA in South India was far higher than any actual experience of stigma. Whether perceived or enacted, HIV-related stigma is widespread in India, and has had a crippling effect.8 PLHA from the subcontinent have lost jobs, been cast out of their homes by family, and denied medical treatment.6,9,10 Some have become victims of intimate partner violence; others have attempted suicide or turned to alcohol and drugs when faced with their diagnosis.11,12 Research in other regions of the world confirms that HIV-related stigma, along with depressive symptoms, anxiety, and substance use, are prominent barriers to medication adherence for people living with HIV.13 Poor adherence to antiretroviral medications and avoiding status disclosure to healthcare providers or sexual partners for fear of public stigma have contributed to increased morbidity, mortality, and accentuated disease transmission.8,14,15 When public stigmas are internalized, PLHA suffer from depression, anxiety, and poor quality of life.16

Investigators have identified both theoretical and practical ways to reduce stigma that may be internalized by a person with HIV. Sometimes, or for some PLHA, the first step to coping with stigma is to disclose to others who may be a source of support.17 However, in the context of extreme stigmas, disclosure must be managed carefully, as some situations have led to further isolation of the person who has disclosed.9 If one is able to disclose to others, contact with others who are living with HIV can lead to the discovery of new coping mechanisms, ability to practice strategies learned, and peer support.18 The extent to which these strategies are employed in India is poorly understood. Therefore, as part of a larger study examining stigma, we carried out a qualitative study to understand how PLHA in South India coped with being HIV-positive and the stigma surrounding HIV.

Methods

Study sites and recruitment

We conducted in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs) with HIV-positive persons affiliated with formal support networks in two cities in the southern state of Tamil Nadu: the Indian Network of Positive Persons and the Positive Women's Network in Chennai, and the Pushes Network in Vellore. We sampled network members purposively, first obtaining permission from the Presidents of each of the three networks to recruit participants from among PLHA registered with them (PLHA typically join these networks after counselor or peer referral). Network coordinators then contacted members to ascertain their willingness to participate. Written informed consent was obtained from each literate respondent. The consent form was read to nonliterate participants who signed their names or affixed their thumb imprint on the consent form. IDI's and FGD's were conducted in a private space within the network office premises. All participants were compensated a nominal sum (Rs.150/- or 3.50 USD) to reimburse their travel costs, calculated based on approximate distances PLHA had to travel to access the network offices.

Guides and conduct of interviews and focus groups

Separate interview and focus group guides were developed. The IDIs were carried out by gender-matched, trained qualitative interviewers, and sought to elicit sensitive personal information about participants' knowledge of HIV, their attitudes towards disclosure, perceptions of stigma and discrimination, any stigmatizing experiences they may have experienced, and how they coped with HIV-related stigma. FGDs, facilitated by a trained researcher, explored stigma-associated barriers to seeking care, social support, and status-disclosure.

Seventeen IDIs (10 in Chennai; 7 in Vellore) and 4 FGDs (2 in Chennai; 2 in Vellore) were carried out. All the IDIs and FGDs were conducted in Tamil and audio-taped with the permission of participants. The FGD and IDI transcripts were transcribed verbatim, translated into English and entered into NVivo (QSR, Australia), a software program for qualitative data analysis that facilitates organization and retrieval of textual data for synthesis and interpretation.

Qualitative analyses

Analyses followed the framework described by Ritchie and Spencer.19 This comprised five stages: (1) familiarization with data; (2) identification of a thematic framework; (3) indexing and charting; (4) mapping; and (5) interpretation.

Familiarization with data involved reading the transcripts several times to gain insights into the issues being studied, following which the transcripts were coded. Initially five transcripts were coded inductively by two independent coders (SK and RM), the coding scheme developed by each of the coders was compared, and any differences in coding were resolved. Coding involved assigning words or phrases to segments of text, which guided the identification of categories and patterns within the data. The development of these categories led to the next stage of evolving a thematic framework that best explained the data. The indexing and charting stage comprised sifting through the data and identifying suitable quotes illustrating the themes. The final stage of analysis, namely mapping and interpreting, involved synthesizing the quotes, categories, and themes, and identifying linkages between them to provide a holistic understanding of the phenomenon of coping with HIV-related stigma. Ethical committee clearance for this study was provided by the Institutional Review Boards of the Christian Medical College, Vellore, and the University of Washington.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Eight men and nine women participated in the IDIs. Of the 8 male participants, 5 were from Chennai and 3 from Vellore. Of the 9 female participants, 5 were from Chennai and 4 from Vellore. The women were younger than the men (mean age 24.6 versus 38.7). While all the 8 men were currently married, only 4 of the 9 female participants were currently married. The remaining 5 were widows. The majority were literate, with most of the men engaged in either skilled or casual labor. Women were equally divided between those who were homemakers, those engaged in casual labor, and those employed as outreach workers by the positive networks.

A total of four FGDs were conducted, separately for men and women. One group of males (n=8) and one group of females (n=9) was conducted in Chennai and a similar pair conducted in Vellore (male=10 participants; female=8 participants). Female FGD participants were younger than male participants (mean age 38.5 versus 38.5). Both men and women were predominantly literate, with only 2 men and 5 women who were nonliterate. The majority of the female FGD participants were homemakers, while the men were employed as casual laborers, as agricultural laborers, or owned a small business.

Conceptual framework and themes of analysis

Context of stigma

The phenomenon of HIV-related stigma as expressed by the participants was characterized by feelings of shame, worthlessness, fear of ostracism, rejection, and guilt. Not being able to live with dignity, coupled with a sense of anger and frustration, was a common thread across most interviews. Three themes summarizing HIV-related stigma emerged: (1) taboo of modes of transmission, (2) sex workers are responsible, and (3) avoiding associating with PLHA.

Taboo of modes of transmission

Participants described an aura of shame associated with the disease and this, coupled with its sexual mode of transmission, accentuated public fear surrounding the disease. Sexual intercourse is the most common mode of HIV transmission in India and is itself a taboo subject. As HIV is associated with promiscuity and promiscuity associated with high levels of stigma, PLHA are intensely afraid of being found out, as this would entail losing face in society and being subject to ridicule.

I must have got it (HIV) through hospital syringes, because, I have never committed any mistakes (sex with other women), but I have gone to hospital several times to get treatment for something or other; who is going to believe this? People will think that I must have got this (HIV) through sex…(Male FGD–Chennai)

Another participant described how the stigma surrounding promiscuity impacted his decision not to disclose his status.

If I disclose my HIV status then people will think that I have got infected through sexual relationship. Both educated and uneducated people would think like that…people think that the person infected with HIV is immoral. The disease is seen as a mark of disgrace and that is why infected people don't like to disclose their status…(Male IDI 2–Chennai)

Sex workers responsible for HIV

Quite a few men believed that they were unlikely to contract HIV, as they had never visited sex workers, although they had engaged in sex with “family women” (i.e., married/unmarried women who are not sex workers).

I cannot understand why I got this disease, I did not go to any prostitutes. Of course I did have sex with this woman who lives nearby, but she is a “family woman.” (Male IDI 4–Vellore).

The belief that HIV was essentially a “pomblai seeku” which literally translated means “women's disease,” was commonly expressed. However, in this context it implied sex workers who, by virtue of their trade, were seen as the main carriers of the disease and consequently held responsible for spreading the disease. A few men were aware that HIV was also transmitted through infected syringes and blood transfusion and were emphatic in stating that they had got infected through these means, rather than from women. Such men felt angry that people looked upon them with the same sense of disgust they showed to other PLHA who had got infected after “committing a mistake.”

Avoid associating with PLHA

Fear of being seen with or found associating with PLHA was consistently expressed by many participants. Despite awareness campaigns, people feared contracting the infection simply by talking to a PLHA. There was also the sense of loss of “prestige,” if people were seen to be associated with a PLHA. This tended to make PLHA feel deeply marginalized.

…they [the public] still think that HIV will spread to others if they talk to HIV infected people…even now they look at me the way they looked at me when I was sick. They are scared to be with me…they are afraid because they think that they might also get infected with this disease. They don't like a person like me living in their family, and this is also a prestige issue for them. They are afraid about what people will say about them also. (Male IDI 2–Vellore)

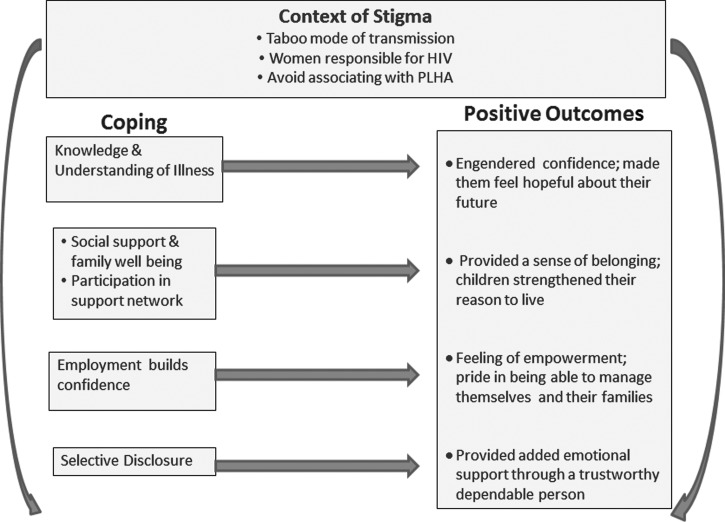

Given these deeply ingrained cultural beliefs and taboos, coping with HIV-related stigma in India is particularly challenging. Despite this, PLHA adopted a number of positive strategies, the use of which enhanced their quality of life. These are classified under five themes: (1) Clear Knowledge and Understanding of HIV, (2) Social Support and Family Well Being, (3) Participation in Positive Networks, (4) Selective Disclosure, and (5) Employment Building Confidence (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Conceptual framework: Coping positively with HIV and HIV-related stigma.

Coping with HIV-related stigma

Clear knowledge and understanding of HIV infection

How people perceived and understood their illness played a pivotal role in influencing how they coped with the stigma surrounding the illness. For a long time following their diagnosis, most PLHA had very poor understanding about HIV and its possible implications. They tended to perceive it as a dreaded “killer disease” from which there was no hope of survival. Women, more than men, had very little awareness and understanding about the disease. Most had contracted the infection from their husbands and had learnt about their status during pregnancy when they were tested at their antenatal check-up. They looked upon HIV with fear because they believed it would lead to an early and painful death. This was compounded by the fear of being ‘found out,’ which would result in ostracism and loss of face among family and community members. Further, as they were often diagnosed before their husbands by virtue of their antenatal care visit, they were viewed with suspicion and held responsible for transmitting the disease.

I was very depressed (when she learnt of her diagnosis) and felt very bad. I was very scared as to what was going to happen to me. What did I do wrong? I was so ashamed and felt so depressed. (Female IDI 4–Chennai)

However, after they became affiliated with the positive support groups and began to regularly attend meetings, their understanding improved. Interacting with other PLHA helped them learn more about the disease and they began to feel better equipped to deal with the stigma they faced. In addition, regular visits to the hospital where they had an opportunity to talk to doctors and counsellors and see other PLHA seeking care enhanced their knowledge about HIV, helping them to cope better.

Now I have become very bold and have gained a lot of self-confidence. I am now bold enough to face my future. There are still several PLHA who live in fear of being found out and are under tremendous stress. Even I was like that before but now I have changed. I have learnt a lot gradually from doctors and counsellors. (Female IDI 3–Chennai)

Added to this, their improved health following treatment adherence made them feel and look better, contributing to greater family and community acceptance.

My husband had got that skin problem and had boils all over on his face—even my children won't go near him and people would stare at him. But now he is fully alright he does not have any skin problem…He has medicines properly and he takes food at correct time. Now so much of improvement is there. (Female IDI 5–Chennai)

Social support and family well-being

Amidst reports of stigmatizing experiences, some participants also reported positive experiences. They spoke of the support given them by their families and of how their relationships remained unaffected even after they learned the respondent's HIV status. In other cases, participants spoke of friends coming to their aid, of wives coming to terms with their husband's HIV status, and of the resilience of many women who against all odds were able to overcome many barriers and come out stronger for it.

They (family) treat me the way they always used to treat me and there is no difference. No one discriminates against me. My mother, father, brother, brother's wife, they are all nice to me and our relationship remains the same…This makes me feel less bad about myself and I feel more able to deal with my life as I have the support of my family (Male IDI 6–Vellore).

Support from the spouse proved invaluable for many PLHA. Many HIV-positive men spoke about the care and understanding given them by their wives, which helped tide them over their difficult times and regain their desire to live. They infused in them a sense of confidence, impressed upon them the need to look ahead and not to wallow in self-pity.

It is because of my wife, I should say, because she helped me a lot. I had itching in the night times and she was with me and took care of me. She used to give me medicine every day…I suffered a lot, I had to go to toilet every now and then, sometimes I would go to toilet for about 40 times and she stood by me in those difficult times. That is what, actually, made me think about living rather than dying…my wife is my big support. (Male IDI 8–Vellore).

The presence of children and their welfare was a major focus in our participants' lives. It helped pull participants out of their own sorrow and self-absorption and instead made them focus on working towards providing a good future for their children. In other cases women had come to terms with their husbands “transgressions” and wanted only that they both remain healthy so that they could nurture their children to adulthood. Thus, for the sake of their children, many HIV-infected persons started taking better care of their health, looking for and holding jobs and generally trying not to think too much about their HIV infection. This was a dominant theme with both women and men who believed that they now needed to live for the sake of their children.

Nothing is going to happen if I keep on worrying, so I take my medicines regularly and I keep doing my work daily and never worry about my future…I have two daughters, until I settle them I can't think of death…. (Female IDI 4–Vellore).

Participation in positive networks

Becoming members of the positive networks and participating in their various activities gave them access to a network of peers with whom they could confide and experience a sense of belonging. Some served as outreach workers in these networks which entailed encouraging other PLHA to seek health care early, giving them guidance and support, and educating them about living with HIV. This gave them a sense of purpose and of feeling useful which was deeply fulfilling. Over time and following regular interactions with health care providers and members from the positive networks, many men and women had learnt to manage their lives.

Once diagnosed with HIV, people will need help. Like the time I was angry at my husband, and feeling suicidal. The counsellors told me how to practice safer sex, how to deal with it emotionally. But it didn't really help because I felt very shocked. What really helped was when I came to the networks and saw that there were many others like me. (Female IDI 2–Chennai)

Employment builds confidence

Employment also helped PLHA cope with HIV stigma. Most men reported feeling shocked and fearful when they learnt of their HIV status. Women experienced not just shock and fear but also a deep seated anger towards their husbands from whom they had contracted the infection. What seemed to have helped them all cope more effectively was their confidence in themselves, partly engendered by becoming financially independent. For men, many of whom had lost jobs because of illness, the fact that they were now earning and in a position to care for their families provided a tremendous boost to their confidence.

Though I am infected with HIV I am now healthy, and now go to work, I can earn and I can support the family. I am infected with HIV and that cannot be changed…Whatever be the work I am ready to do, I have started to learn all kinds of jobs to live, and this helps me lead a simple and better life. (Male IDI 4–Chennai).

For women in particular, many of whom led cloistered lives, exposure to the disease followed by the death of their husbands had forced them into caring for themselves and providing for their families. They had taken jobs which provided a modicum of financial independence and infused them with a sense of confidence, hitherto unknown to them.

It's just how you take things…depends on your state of mind…We all have different ways of dealing with situations. I have developed this courage myself. I was seeking a job at an NGO earlier. When people there met me recently, they were surprised to see how much I had changed. I never used to talk so much…This lady told me that I had clarity in my speech, in the way I looked and that I had really changed a lot. I told her that having a job in hand alone has led me to this state…Even if relatives ostracise me, it's the job that will keep me going…(Female IDI 2–Chennai)

Selective/assisted disclosure

Keeping the disease a secret from family and friends was commonly reported by most participants. Cases of husbands not disclosing to wives were reported, albeit only a few. This reluctance to disclose stemmed from a combination of factors which included concerns about causing distress to their wives, about losing their love and trust and the fear of being abandoned by them. Such emotional compulsions outweighed the importance of revealing their status to their wives or suggesting that they test for HIV. A male PLHA from Vellore rationalized by stating that with time once their relationship was further cemented, he would definitely disclose to her.

Cases of families finding out about the HIV status of their relative and wanting to get rid of them either by abandoning them or by killing them were also reported. Clearly, such instances strongly influenced PLHA's decisions regarding being selective about to whom they disclosed their status.

When I was pregnant, my relatives came to know I was HIV+. My brother-in-law called my in-laws and told them that they should kill me and the unborn child.…He said ‘push her from the train to Chennai and kill her. Such people should not live’. He even gave an idea saying, mix poison in a soft drink and give it to her and leave her in the train half-way. (Female FGD–Chennai)

These types of severe consequences suggest that people with HIV in India need to make decisions about whether or not to disclose extremely carefully. They should never feel pressured to disclose, as in some cases, disclosure can put them at risk for violence.

There were other cases of men bringing their wives to the hospital to meet with the HIV counselor/doctor. These husbands felt uncomfortable disclosing their HIV status and sought assistance. Often these counselor-assisted disclosures were followed by passionate emotional outbursts from their wives. Some would even leave their husbands and go to their parent's home. Thus, disclosure of HIV status brought with it hazards, prompting many PLHA to think twice before revealing their status.

It was the doctor, who called her (his wife), explained my condition. I was not able to disclose my status to her as well as to my family members, so, the doctor advised me to call my relatives and I told my wife that she has to come anyway as it is recommended by the doctor. He (the doctor) explained my condition in such a way that it helped my family members to understand the problem. (Male IDI 3–Chennai).

In contrast, several PLHA had gone ahead and disclosed to their spouses with a few even disclosing to close family members and friends. Notably, participants reported that selective disclosure aided their coping, as they appreciated the support they derived from these individuals who not only assisted them with their health care needs (e.g., accompanying them to the doctor, checking their medication compliance, etc.), but also provided them much needed emotional support.

I became very sick once. I thought since I don't have a husband, I should at least disclose my status to my father, so if I died somebody might take care of my children. My dad is like a friend so I could tell him everything and he understands me…disclosure depends on the person's mentality. Only if they can accept this situation can you disclose (Female IDI 2–Chennai).

Discussion

This qualitative study sought to understand how PLHA affiliated with support networks in Southern India coped with HIV and HIV-related stigma. Specifically, participants identified how their knowledge of HIV infection, participation in support networks, their attitudes and experiences relating to disclosure, family and social support, and employment enhanced their ability to cope with stigma.

PLHA in this study described living in constant fear of unanticipated disclosure of their HIV status, as this would bring shame to them and their families along with the label that they were “immoral” or “bad,” and this is consistent with other studies from India.7,20 Such was the sense of self-stigma that many participants coped by isolating themselves or deliberately keeping aloof from friends and family to avoid awkward situations that could result in status disclosure. This stigma-induced isolation is highly problematic, particularly when it leads to poor engagement in care and medication adherence.5,21–23 Given the benefits of ART, the decrease in adherence associated with HIV-related stigma is somewhat paradoxical. In Okoror's exploration of the cultural context of HIV stigma on ART adherence,24 the fear of anticipated and enacted stigmas acted as a catalyst for PLHA to strictly adhere to their ART regimen. Looking sickly and ill was seen as a sign of being infected with HIV. By complying with their ART regimens, PLHA were able to look and feel healthy, reducing or even eliminating enacted stigma.

The particularly intense feeling of shame and fear of disclosure associated with HIV in the Indian context is due in large part to the belief that only those who are sexually promiscuous or who visit sex workers contract HIV. Participants found disclosure to be extremely challenging as many feared “being judged” and “being rejected”.25 Nondisclosure, denial, and hiding may also be a way of coping, especially if it protects one from stigma.26 However, nondisclosure gives rise to intense anxieties about keeping an HIV status secret, which can add to the distress. We found that some PLHA, in anticipated fear of being rejected or abandoned, had refrained from disclosing their status even to their spouses/sexual partners, putting them at increased risk of HIV infection. Public health programmes that work towards removing the aura of ‘shame’ and ‘guilt’ that surrounds issues concerning sex and sexuality in India would be an important step towards reducing stigma, enhancing disclosure and reducing anxiety experienced by PLHA in India.

In addition to shame, through these narratives, it was apparent that despite a lapse of over 20 years since HIV was first identified in India, poor understanding and awareness about the disease accentuated fears about stigma and disclosure. The belief that commercial sex workers were the main source of disease transmission and that HIV afflicted only those who were “bad” only served to highlight the strong moralistic overtones that continue to colour the disease. Women knew less than men and most PLHA took several months before they really began to understand their disease. Yet with understanding of their disease came a new found sense of confidence and a realization that they could continue to live fairly healthy and productive lives. This is consistent with other studies27 that have described how PLHA, after gathering more information about HIV/AIDS, perceived renewed hope and began to lead healthier lifestyles. Among rural South Indian women, better knowledge about HIV/AIDS protected against “heard stigma” (stories about other PLHA being mistreated and discriminated against) because it enabled women to know the facts and therefore feel less fearful.28 Considering the role of enhanced understanding of the disease in infusing PLHA with a sense of confidence, ensuring that accurate information about HIV is imparted to PLHA soon after diagnosis could improve their ability to cope with their infection, and should be a priority in HIV care settings.

The fact that several PLHA spoke positively of their HIV experiences deserves special mention. Many PLHA narratives attested to the support and love received from both family and friends and of how their relationships remained unchanged following disclosure of their status. Such a supportive family environment greatly contributed to PLHA coping more effectively both emotionally—in terms of feeling loved—and instrumentally—in terms of having someone to help care for their health needs. The presence of children proved invaluable to many PLHA as it gave them a reason to live. Family support also played a critical role in helping Pacific Islander PLHA cope with their illness, and children in this setting were a similar source of strength and support to their parents.29 Programs in India that work towards building better understanding of HIV and inculcating positive attitudes towards PLHA among families may lead to quicker acceptance of family members living with HIV,26 thereby enhancing their capacity to effectively support PLHA.

The value of having a job with a steady source of income and the accompanying independence and confidence was particularly evident among women, many of whom had earlier lived totally cloistered lives with their husbands. Additional incorporation of skills development and employment assistance into support programs could amplify their role in positive coping. Working as outreach workers for PLHA support groups provided dual benefits: the workers felt empowered, and the recipients gained confidence and hope for the future. This is consistent with evidence from Asia, Africa, and Latin America where involving PLHA in providing services for other PLHA empowered them and gave them a sense of fulfilment.30 Nyblade et al.31 also observed that becoming part of a support group of persons with the same condition is one way of coping with stigma.

This study had certain limitations. First, it was confined to PLHA who were affiliated with support networks and whose understanding of HIV and experiences of stigma may differ from those not belonging to a support network. PLHA not involved in support networks may experience greater isolation, compounding the stigma, and may exhibit different coping behavior. Second, families and friends of PLHA were not included. Their experiences of living with an HIV-infected person may yield valuable insight into the phenomenon of coping with the stigma of HIV and how to harness family support for PLHA. This should be explored in future studies. Last, the absence of interviews with leaders and decision makers of support networks limited our understanding of how services could be expanded to include families and friends of PLHA, who also experience stigma, and this also merits further exploration.

Despite these limitations, these narratives of HIV-positive men and women highlight the challenges they face in coping both with HIV and the related stigma. The positive coping behaviors exhibited by PLHA here (enhancing knowledge of HIV infection, becoming part of support networks, selective/assisted disclosure, becoming employed and financially empowered) may be effective targets for intervention development. Listening to the voices of these PLHA can provide a deeper understanding of HIV-related stigma, sensitize care providers, and inform culturally relevant intervention programs.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by a grant from the Puget Sound Partners for Global Health (Award #26145). KRM and LEM's contribution to this work was partially supported by the University of Washington (UW) Center for AIDS Research (NIH/NIAID AI27757). The authors would like to thank the staff of the Indian Network of Positive Persons, Positive Women's Network, and the Pushes Network for assistance with study logistics, as well as the study participants who generously gave of their time.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Carson VB. Prayer, meditation, exercise, and special diets: Behaviors of the hardy person with HIV/AIDS. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 1993;4:18–28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chesney MA, Folkman S. Psychological impact of HIV disease and implications for intervention. Pyschiatr Clin N Am 1994;17:163–182 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Logie C, James L, Tharao W, Loutfy M. Associations between HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, gender discrimination, and depression among HIV-positive African, Caribbean, and Black women in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:114–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudoir SR, Fisher JD, Simoni JM. Understanding HIV disclosure: A review and application of the Disclosure Processes Model. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:1618–1629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao D, Feldman B, Fredericksen R, et al. . A structural equation model of HIV-related stigma, depressive symptoms, and medication adherence. AIDS Behav 2012;16:711–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adewuya AO, Aakanjuola MRO. Social distance towards people with mental illness amongst Nigerian university students. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol 2005;40:865–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas BE, Rehman F, Suryanarayanan D, et al. . How stigmatizing is stigma in the life of people living with HIV: A study on HIV positive individuals from Chennai, South India. AIDS Care 2005;17:795–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UNAIDS. HIV-related stigma, discrimination and human right violations. Case studies of successful programmes. 2005.

- 9.Chandra PS, Deepthivarma S, Manjula V. Disclosure of HIV infection in South India: Patterns, reasons and reactions. AIDS Care 2003;15:207–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steward WT, Herek GM, Ramakrishna J, et al. . HIV-related stigma: Adapting a theoretical framework for use in India. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:1225–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandra PS, Ravi V, Desai A, Subbakrishna DK. Anxiety and depression among HIV-infected heterosexuals—A report from India. J Psychosom Res 1998;45:401–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Saggurti N, Balaiah D, Raj A. Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among married Indian women. JAMA 2008;300:703–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Tugenberg T. Social relationships, stigma and adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 2006;18:904–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chesney MA, Ickovics J, Hecht FM, Sikipa G, Rabkin J. Adherence: A necessity for successful HIV combination therapy. AIDS 1998;13:S271–S278 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumarasamy N, Safren SA, Raminani SR, et al. . Barriers and facilitators to antiretroviral medication adherence among patients with HIV in Chennai, India: A qualitative study. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2005;19:526–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee RS, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Internalized stigma among people living with HIV-AIDS. AIDS Behav 2002;6:309–319 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corrigan PW, Rao D. On the self-stigma of mental illness: Stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Can J Psychiatr 2012;57:464–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao D, Desmond M, Andrasik M, et al. . Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of the ‘Unity Workshop’: An internalized stigma reduction intervention for African-American women lving with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2012;26:614–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research. London: Routledge, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mawar N, Paranjape R. Live and let live: Acceptance of people living iwth HIV/AIDS in an era where stigma and discrimination persist. ICMR Bulletin 2002;32:105–114 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mugavero M, Lin H, Allison J, et al. . Racial disparities in HIV virologic failure: Do missed visits matter? J Acq Immun Def Synd 2009;50:100–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mugavero M, Ostermann J, Whetten K, et al. . Barriers to antiretroviral adherence: the importance of depression, abuse, and other traumatic events. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2006;20:418–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kingori C, Reece M, Obeng S, et al. . Impact of internalized stigma on HIV prevention behaviors among HIV-infected individuals seeking HIV care in Kenya. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012;26:761–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okoror TA, Falade CO, Olorunlana A, Walker EM, Okareh OT. Exploring the cultural context of HIV stigma on antiretroviral therapy adherence among people living with HIV/AIDS in southwest Nigeria. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:55–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Insideout Research. siyam'kela: measuring HIV/AIDS related stigma: UNESCO HIV and Health Education Clearinghouse, 2003. Available at: http://hivhealthclearinghouse.unesco.org/library/documents/siyamkela-measuring-hivaids-related-stigma-hivaids-stigma-indicators-tool (Last accessed October9, 2014)

- 26.Brown L, Trujillo L, Macintyre K.Interventions to Reduce HIV/AIDS Stigma: What have we learned?: Population Council, 2001. Available at: http://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/horizons/litrvwstigdisc.pdf (Last accessed October9, 2014)

- 27.Makoae LN, Greeff M, Phetlhu RD, et al. . Coping with HIV-related stigma in five African countries. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2008;19:137–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nyamathi A, Ekstrand M, Zolt-Gilburne J, et al. . Correlates of stigma among rural Indian women living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav 2013;17:329–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pacific Regional HIV/AIDS Project Working Group. HIV and AIDS-Related Stigma and Discrimination: Perspectives of HIV-Positive People in the Pacific: Pacific Island AIDS Foundation, 2009. Available at: http://www.pacifichealthvoices.org/files/stigmaanddiscriminationreportpiaf.pdf (Last accessed October9, 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pulerwitz J, Michaelis A, Weiss E, Brown L, Mahendra V. Reducing HIV-related stigma: Lessons learned from Horizons research and programs. Public Health Rep 2010;125:272–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nyblade LC, Pande R, Mathur S, et al. . Disentangling HIV and AIDS Stigma in Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zambia. 2003. Available at: http://www.icrw.org/publications/disentangling-hiv-and-aids-stigma-ethiopia-tanzania-and-zambia (Last accessed October9, 2014)