Abstract

Outpatient care for people living with HIV is delivered in diverse settings. Differences in setting may impact HIV outcomes. We evaluated HIV-infected adults in care at Ryan White-funded clinics in Philadelphia, PA, between 2008 and 2011 to determine how setting of care (hospital versus community-based) influenced HIV outcomes. Clinics were categorized as hospital-based if they were located onsite at a hospital. The composite outcome was completion of the final three steps of the HIV care continuum: (1) retention in care; (2) use of antiretroviral therapy (ART); and (3) viral suppression. Mixed-effects logistic regression, accounting for patient and clinic factors, examined the relationship between care setting and the outcome. In total, 12,637 patients, contributing 32,515 patient-years, received care at 25 clinics (12 hospital-based). Women, non-Hispanic blacks, those with private insurance, and individuals with higher household incomes more commonly attended hospital-based clinics (p<0.05). Of the 12,962 patient-years (40%) during which patients attended community-based clinics, 59% met the outcome. Similarly, 59% of the 19,553 patient-years (60%) in which patients attended hospital-based clinics met the outcome. Adjusting for patient and clinic factors, setting was not associated with the outcome (adjusted odds ratio=1.24, 95% CI=0.84–1.84). In summary, demographics differ among patients visiting hospital and community-based clinics. Completion of the final three steps of the HIV care continuum did not vary between hospital and community-based clinics, which may reflect advances in HIV therapy and the wide availability of HIV care resources.

Introduction

The HIV care continuum is an effective framework for improving the health of people living with HIV (PLWH) and for achieving the public health benefits of antiretroviral therapy (ART).1–3 Steps in the continuum include those prior to engagement in HIV care (diagnosis and linkage to care) and those after engagement (retention in care, receipt of ART, and HIV viral suppression). Major challenges exist in completing the final three steps of the continuum. It is estimated that 51–84% of those linked to care meet national standards of retention in care, 80–89% of patients in care receive ART, and 72–81% of patients on ART achieve viral suppression.2–11 Accordingly, the United States (US) Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that only 25% of all PLWH are virally suppressed.12

Numerous factors contribute to successfully completing continuum steps, including patient characteristics, quality of the patient–provider relationship, and the structure of healthcare delivery.13–18 However, most prior studies have focused on patient-level factors, such as sociodemographic, clinical, and behavioral characteristics, with few examining the effects of the healthcare environment on HIV outcomes.13,19–22

Outpatient care for PLWH is delivered in diverse settings. While many clinics offer similar medical services, including delivery of HIV-specific care and prescription of ART, they often have unique identities that emerge from different care models, organizational structures, academic affiliations, and funding sources.23,24 Many HIV-infected persons receive care at community-based HIV clinics that often meet the definition of a community health center (CHC): a private, nonprofit organization that receives public funding and provides comprehensive primary health services to residents of a defined geographic area that is medically underserved.25 Alternatively, PLWH may engage in care at clinics located within large ambulatory practices, health systems, or academic health centers. The Ryan White Program (RWP) funds outpatient medical care for many PLWH across the US and thus supports a diverse range of HIV care delivery settings and models.26

Differences in clinic settings may impact health utilization and outcomes. In a nationally representative survey of non-federal, office-based physicians, patients seen at CHCs had more visits to their provider than those seen at private outpatient offices.27 Similarly, analyses of three national primary care surveys demonstrated lower continuity of care in hospital outpatient departments than either physicians' offices or CHCs.28 In a retrospective study of 854 HIV-infected patients, Chu et al. compared rates of viral suppression and immunologic success (defined as a 100 cell/mm3 increase in CD4 count) among those who received care at a hospital-based specialty practice to those seen at a community-located primary care clinic.29 No significant differences in viral suppression and immunologic success were observed. However, this study was limited by its small sample size and use of data from only two clinical sites within the same healthcare network.

To better understand how the setting of care influences completion of the final three steps of the HIV care continuum (retention in care, use of ART, and viral suppression) in hospital versus community-based HIV clinics, we used data from a large, geographically based cohort of HIV clinics. An appreciation of the relative strengths of hospital and community-based HIV clinics is important and will help identify targets for improving HIV outcomes in each setting.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of HIV-infected adults in care at RWP funded clinics in the Philadelphia, PA, eligible metropolitan area (EMA) between 2008 and 2011. Twenty-five HIV clinics treated adults and received RWP funding during the study period, representing approximately 71% of all PLWH in care in the City (unpublished data, City of Philadelphia Department of Public Health). All HIV-infected adults (age ≥18 years) engaged in care, were eligible for inclusion. Patients were engaged in care if they had at least one primary HIV visit and one CD4 test in a calendar year, between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2011, consistent with criteria in prior studies.7,30–32 Thus, each individual could contribute 1, 2, 3, or 4 years of observation to the study analysis.

Data collection

Data were extracted from CAREWare, a Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) recommended data management system containing demographic, laboratory, pharmacy, and health service utilization information for all patients seen at RWP funded clinics in the Philadelphia EMA. Clinics abstract patient-level information from medical records of all patients in care, not only those covered under the RWP. After quality control and verification, data are sent to the City of Philadelphia Department of Public Health AIDS Activities Coordinating Office (AACO) and combined across clinics to produce a uniform database. Each patient in the database has a unique identifier, independent of personal information and site of care. Periodic chart reviews and site visits are undertaken to verify the accuracy and completeness of data abstraction and entry.

Clinic-level data annually collected by the City of Philadelphia Department of Public Health AACO, in combination with responses to a structured questionnaire completed by administrators at all adult Philadelphia RWP funded clinics in February 2013, were used to determine the type of care setting and availability of onsite HIV case management and onsite clinical pharmacist(s) during the study period. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Pennsylvania and the City of Philadelphia Department of Public Health.

Patient sociodemographic and clinical variables

For each calendar year of observation, patients' age as of January 1 was divided into four groups: 18–29, 30–39, 40–49, and 50 years or older. Race/ethnicity was categorized as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other/unknown. Self-reported HIV transmission behavior was grouped into heterosexual, men who had sex with men (MSM), injection drug use (IDU), and other/unknown. Patients who had IDU in combination with another risk factor (e.g., MSM, heterosexual transmission) were classified as IDU. Insurance coverage in each year was categorized as private, Medicaid, Medicare (including those with dual eligibility), uninsured, or other/unknown. Patients whose care was funded through RWP were considered to be uninsured. Annual household income was divided into <$10,000 and ≥$10,000 according to CDC classifications.33 Median CD4 cell count, based on all collected values in each year, was grouped as ≤350, 351–500, or >500 cells/mm3.34 These categories were selected based on differential indications for initiating ART, and to account for changes in HIV treatment guidelines over the 4-year study period.34–36

Clinic variables

Clinics were categorized as hospital-based if they were located onsite at a hospital or hospital campus and designated as offering case management and access to a clinical pharmacist if these services were located onsite.

Outcome variable

The outcome of interest was completion of all of the final three steps of the HIV care continuum: retention in care, use of ART, and viral suppression. Retention in care was based on the US National HIV/AIDS Strategy metric, which defines retention as having two or more outpatient visits separated by ≥90 days during a calendar year.37 Patients were designated as using ART if they received at least three antiretroviral drugs (excluding ritonavir), a definition consistent with prior literature, at the last outpatient visit in the calendar year.7,38,39 Fixed-dose combination pills were counted as the number of individual drug components. Outpatient visits refer only to primary HIV care appointments and do not include nursing, pharmacy, laboratory, or other types of visits. HIV viral suppression was classified as last annual HIV-1 RNA ≤200 copies/mL. Patients had to meet each of these steps to be assigned as completing the care continuum.

Statistical analyses

The patient-year was the unit of analysis, reflecting the common practice of measuring retention in care, use of ART, and viral suppression on a calendar year basis. Each patient could contribute one observation per calendar year. Analyses were limited to patient-years in which the patient was at least 18 years and in care, defined by having at least one primary HIV visit and one CD4 test in the year. Thus, the number of patient-years was not constant across patients or years.

We excluded the first calendar year in care for 5400 new patients and the calendar year of death for 430 patients, as they did not provide adequate time to measure the outcome. After excluding these patient-years, 24% of the sample contributed 1 year of data; 22% contributed 2 years; 24% contributed 3 years; and 30% contributed 4 years.

Statistical comparisons of demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample across calendar years were conducted using the X2 test for trend. Multivariate logistic regression examined demographic (age, sex, race/ethnicity, HIV transmission behavior, insurance coverage, annual household income) and clinical factors (median CD4 cell count) associated with care setting (attending a hospital-based vs. community-based clinic), adjusting for calendar year.

To assess the relationship between care setting and the outcome of interest (completion of the final three steps of the HIV care continuum), mixed-effects logistic regression was used.40 The model included random effects for clinic and patient to account for within patient and within clinic correlation. Fixed effects included care setting and potential confounders: age, sex, race/ethnicity, HIV transmission behavior, insurance coverage, annual household income, median CD4 cell count, calendar year, and availability of onsite case management and clinical pharmacy services.

We identified 429 patient-years, 1.3% of the sample, in which patients had no HIV-1 RNA test reported; these observations were excluded from the primary analysis. A sensitivity analysis was conducted assuming all patient-years with missing HIV-1 RNA were not suppressed (HIV-1 RNA >200 copies/mL). Two-sided testing was used, with a p value of<0.05 considered significant. Analyses were conducted using STATA 12.1 (College Station, TX).

Results

Between 2008 and 2011, 12,637 patients, contributing a total 32,515 patient-years, were in care at Philadelphia EMA RWP clinics (Table 1). The number of patients in care increased from 6406 patients in 2008 to 9388 in 2011. In each year, the majority of patients was male, of minority race/ethnicity, and had heterosexual contact as their HIV mode of transmission. Most patients had Medicaid insurance and yearly income less than $10,000. Across all 4 years, the proportion of patients retained in care and on ART increased from 79% to 85% (p<0.01) and 83% to 88% (p<0.01), respectively. The percent of patients with median CD4 count above 500 cell/mm3 increased from 43% to 51% (p<0.01), while the proportion virally suppressed increased from 64% to 77% (p<0.01).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Study Population by Year

| Calendar year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | 2008 N=6406 (%) | 2009 N=8197 (%) | 2010 N=8524 (%) | 2011 N=9388 (%) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–29 | 636 (9.9) | 834 (10.2) | 947 (11.1) | 1077 (11.5) |

| 30–39 | 1298 (20.3) | 1505 (18.4) | 1453 (17.1) | 1557 (16.6) |

| 40–49 | 2579 (40.3) | 3216 (39.2) | 3189 (37.4) | 3303 (35.2) |

| ≥50 | 1893 (29.5) | 2642 (32.2) | 2935 (34.4) | 3451 (36.8) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 4121 (64.3) | 5328 (65.0) | 5588 (65.6) | 6087 (64.8) |

| Female | 2285 (35.6) | 2869 (35.0) | 2936 (34.4) | 3301 (35.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 1044 (16.3) | 1526 (18.6) | 1518 (17.8) | 1636 (17.4) |

| Black | 4306 (67.2) | 5357 (65.4) | 5584 (65.5) | 6138 (65.4) |

| Hispanic | 864 (13.5) | 1046 (12.8) | 1108 (13.0) | 1185 (12.6) |

| Other/unknown | 192 (3.0) | 268 (3.3) | 314 (3.7) | 429 (4.6) |

| HIV risk factor | ||||

| Heterosexual | 3104 (48.5) | 3891 (47.5) | 4001 (46.9) | 4409 (47.0) |

| MSM | 1851 (28.9) | 2537 (31.0) | 2715 (31.9) | 3040 (32.4) |

| IDU | 1219 (19.0) | 1379 (16.8) | 1433 (16.8) | 1455 (15.5) |

| Other/unknown | 232 (3.6) | 390 (4.8) | 375 (4.4) | 484 (5.2) |

| Insurance | ||||

| Private | 994 (15.5) | 1556 (19.0) | 1392 (16.3) | 1461 (15.6) |

| Medicaid | 3372 (52.6) | 3997 (48.8) | 4390 (51.5) | 5029 (53.6) |

| Medicare | 836 (13.0) | 1320 (16.1) | 1385 (16.3) | 1440 (15.3) |

| Uninsured | 1093 (17.1) | 1233 (15.0) | 1306 (15.3) | 1397 (14.9) |

| Other/unknown | 111 (1.7) | 91 (1.1) | 51 (0.6) | 61 (0.7) |

| Household income | ||||

| <$10,000 | 4625 (72.2) | 5205 (63.5) | 5232 (61.4) | 5750 (61.3) |

| ≥$10,000 | 1781 (27.8) | 2992 (36.5) | 3292 (38.6) | 3638 (38.8) |

| Median CD4 cell count | ||||

| ≤350 cell/mm3 | 2164 (33.8) | 2598 (31.7) | 2442 (28.7) | 2578 (27.5) |

| 351–500 cell/mm3 | 1498 (23.4) | 1896 (23.1) | 2024 (23.7) | 2003 (21.3) |

| >500 cell/mm3 | 2744 (42.8) | 3703 (45.2) | 4058 (47.6) | 4807 (51.2) |

| Retained in care | ||||

| No | 1317 (20.6) | 1621 (19.8) | 1978 (13.3) | 1393 (14.8) |

| Yes | 5089 (79.4) | 6576 (80.2) | 7392 (86.7) | 7995 (85.2) |

| Use of ART | ||||

| No | 1070 (16.7) | 1109 (13.5) | 1208 (13.3) | 1095 (11.7) |

| Yes | 5336 (83.3) | 7088 (86.5) | 7868 (86.7) | 8293 (88.3) |

| Viral suppression | ||||

| No | 2189 (34.2) | 2226 (27.2) | 1978 (23.2) | 2010 (21.4) |

| Yes | 4110 (64.2) | 5870 (71.6) | 6472 (75.9) | 7246 (77.2) |

| Missing | 107 (1.7) | 101 (1.2) | 74 (0.9) | 132 (1.4) |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; HET, heterosexual transmission; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IDU, injection drug use; MSM, men who have sex with men.

In total, patients visited hospital-based clinics in 60% of patient-years (Table 2). In multivariate analyses, women (adjusted odds ratio 1.45, 95% confidence interval 1.34–1.57) and non-Hispanic blacks (1.07, 1.01–1.13) were significantly more likely to visit a hospital-based clinic than men and non-Hispanic whites, respectively. Likewise, individuals with a higher yearly income more commonly attended hospital-based clinics (1.13, 1.11–1.15). Patients with Medicaid (0.95, 0.93–0.97), Medicare (0.96, 0.93–0.98), or who were uninsured (0.82, 0.80–0.84) were less likely to attend hospital-based clinics than those with private insurances.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics Associated with Use of Hospital-Based Clinics

| Characteristic | Use of community-based clinics N=12,962 PYs (%) | Use of hospital-based clinics N=19,553 PYs (%) | AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–29 | 1219 (9.4) | 2275 (11.6) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 30–39 | 2412 (18.6) | 3401 (17.4) | 1.00 (0.97,1.04) |

| 40–49 | 5004 (38.6) | 7283 (37.3) | 1.00 (0.95,1.03) |

| ≥50 | 4327 (33.4) | 6594 (33.7) | 1.01 (0.96,1.05) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 9118 (70.3) | 12006 (61.4) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Female | 3844 (29.7) | 7863 (38.6) | 1.45 (1.32,1.57) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 2737 (21.1) | 2987 (15.3) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Black | 8122 (62.7) | 13263 (67.8) | 1.07 (1.01,1.13) |

| Hispanic | 1526 (11.8) | 2677 (13.7) | 1.02 (0.95,1.09) |

| Other/unknown | 577 (4.5) | 626 (3.2) | 0.98 (0.93,1.03) |

| HIV risk factor | |||

| Heterosexual | 5496 (42.4) | 9909 (50.7) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| MSM | 4690 (36.2) | 5453 (27.9) | 1.04 (0.99,1.08) |

| IDU | 2399 (18.5) | 3087 (15.8) | 1.00 (0.95,1.05) |

| Other/unknown | 377 (2.9) | 1104 (5.7) | 1.00 (0.96,1.06) |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | 1594 (12.3) | 3809 (19.5) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Medicaid | 6254 (48.3) | 10534 (53.9) | 0.95 (0.93,0.97) |

| Medicare | 1822 (14.1) | 3159 (16.1) | 0.96 (0.93,0.98) |

| Ryan White/uninsured | 3132 (24.2) | 1897 (9.7) | 0.82 (0.80,0.84) |

| Other/unknown | 160 (1.2) | 154 (0.8) | 0.98 (0.93,1.03) |

| Household income | |||

| <$10,000 | 9117 (70.3) | 11695 (59.8) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| ≥$10,000 | 3845 (29.7) | 7858 (40.2) | 1.13 (1.11,1.15) |

| Median CD4 cell count | |||

| ≤350 cell/mm3 | 3782 (29.2) | 6000 (30.7) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 351–500 cell/mm3 | 2992 (23.1) | 4429 (22.7) | 1.00 (0.99,1.01) |

| >500 cell/mm3 | 6188 (47.7) | 9124 (46.7) | 1.00 (0.98,1.01) |

| Year | |||

| 2008 | 2884 (22.3) | 3522 (18.0) | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 2009 | 3092 (23.9) | 5105 (26.1) | 1.02 (1.01,1.03) |

| 2010 | 3305 (25.5) | 5219 (26.7) | 1.03 (1.02,1.04) |

| 2011 | 3681 (28.4) | 5707 (29.2) | 1.01 (1.00,1.02) |

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; HET, heterosexual transmission; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IDU, injection drug use; MSM, men who have sex with men; PY, patient-year.

Of the 25 clinics, 12 (48%) were hospital-based and 13 (52%) were community-based. Twelve clinics (48%) offered onsite clinical pharmacists (eight hospital-based and four community-based) and the vast majority (92%) had case management services (twelve hospital-based and eleven community-based).

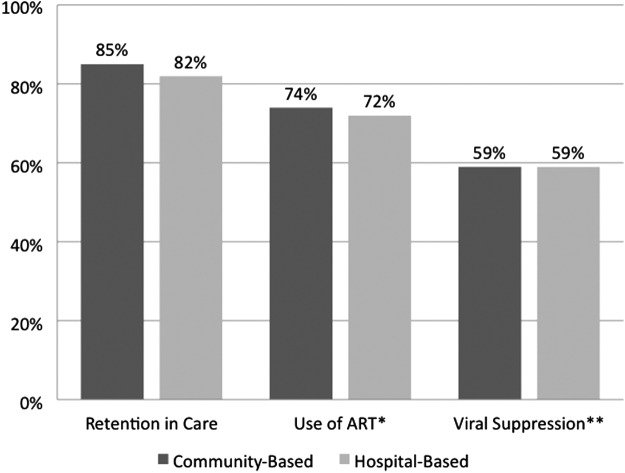

The continuum of care for HIV-infected patients engaged in care at community and hospital-based clinics is presented in Fig. 1. Among the 12,962 patient-years in which patients attended community-based clinics, 85% had patients who were retained in care, 74% had patients who were retained in care and on ART, and 59% had patients who were retained in care, on ART, and virally suppressed. In comparison, among the 19,553 patient-years in which patients attended hospital-based clinics, 82% had patients who were retained in care, 72% had patients who were retained in care and on ART, and 59% had patients who were retained in care, on ART, and virally suppressed.

FIG. 1.

The care continuum for HIV-infected patients in community-based and hospital-based clinics. ART, antiretroviral therapy. *Among patients retained in care; **Among patients retained in care and on ART.

Table 3 presents the multilevel mixed-effects regression model characterizing the association between care setting and completion of the final three steps of the HIV care continuum (i.e., attainment of viral suppression among people retained in care and on ART). Adjusting for clinic and patient factors, patients seen at hospital-based clinics were equally likely to complete the final three steps of the continuum compared to those seen at community-based clinics (1.24, 0.84–1.84). Patients seen at clinics with onsite pharmacists were significantly more likely to meet the outcome compared to those without onsite pharmacists (1.52, 1.01–2.30). Availability of onsite case management was not associated with the outcome (1.33, 0.62–2.89).

Table 3.

Factors Associated With Completion of the Final Three Steps of the HIV Care Continuum (Retention in Care, Use of ART, Viral Suppression)

| Characteristic | AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Care setting | |

| Community-based clinic | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Hospital-based clinic | 1.24 (0.84,1.84) |

| Onsite case management | |

| No | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Yes | 1.33 (0.62, 2.89) |

| Onsite clinical pharmacist | |

| No | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Yes | 1.52 (1.01, 2.30) |

| Age (years) | |

| 18–29 | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 30–39 | 1.65 (1.31, 2.09) |

| 40–49 | 2.47 (1.98, 3.09) |

| ≥50 | 3.85 (3.04, 4.87) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Female | 0.65 (0.56, 0.76) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Black | 0.57 (0.47, 0.69) |

| Hispanic | 0.94 (0.73, 1.21) |

| Other/unknown | 1.09 (0.76,1.55) |

| HIV risk factor | |

| Heterosexual | 1.00 (Ref) |

| MSM | 1.17 (0.97,1.40) |

| IDU | 0.80 (0.67, 0.95) |

| Other/unknown | 1.09 (0.79, 1.49) |

| Insurance | |

| Private | 1.00 (Ref) |

| Medicaid | 0.69 (0.57, 0.83) |

| Medicare | 0.71 (0.57, 0.90) |

| Ryan White/uninsured | 0.89 (0.71,1.13) |

| Other/unknown | 0.74 (0.40,1.38) |

| Household income | |

| <$10,000 | 1.00 (Ref) |

| ≥$10,000 | 1.25 (1.10, 1.44) |

| Median CD4 cell count | |

| ≤350 cell/mm3 | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 351–500 cell/mm3 | 4.54 (3.94, 5.22) |

| >500 cell/mm3 | 13.64 (11.75, 15.82) |

| Year | |

| 2008 | 1.00 (Ref) |

| 2009 | 1.32 (1.15,1.51) |

| 2010 | 1.71 (1.49, 2.00) |

| 2011 | 1.59 (1.39, 1.83) |

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; HET, heterosexual transmission; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IDU, injection drug use; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Older age, higher household income, higher median CD4 cell count, and receiving care in later years were all significantly (p<0.05) associated with completion of the final three steps of the HIV care continuum. Females, non-Hispanic blacks (vs. non-Hispanic whites), individuals with IDU transmission risk (vs. heterosexual risk), and those covered by Medicare or Medicaid (vs. private insurance) were less likely (p<0.05) to meet the outcome (Table 3). Sensitivity analyses categorizing those with missing viral load data as “not suppressed” yielded similar results (results not shown).

Discussion

These results, from a large, geographically based cohort of HIV clinics, confirm those of an earlier study, which found no differences in the rates of virologic suppression and immunologic recovery between patients receiving care at a community-based primary care clinic and those in care at a hospital-based specialty care clinic in Bronx, NY.29 Our findings are encouraging, suggesting that PLWH can achieve similar outcomes independent of clinic setting.

A number of factors may explain our findings, including advances in HIV therapy and the wide availability of HIV care resources. Improvements in the treatment of HIV have led to the advent of effective, better tolerated, and more convenient therapy.41,42 As a result, adherence to ART has improved, the proportion of patients with HIV viral suppression has increased, and HIV-related complications have decreased.43–45 Similarly, data indicate that compliance with HIV treatment guidelines is associated with viral suppression and improved survival.46 The number of HIV education and care resources has increased in recent years and are widely accessible to clinics. One example is the HRSA-sponsored in+care campaign, a national quality improvement effort aimed at optimizing retention in care.47,48 This initiative offers clinics the opportunity to participate in educational webinars, receive individualized coaching, and interact with national HIV experts. Similarly, many online training centers can assist clinics in designing and implementing interventions to improve outcomes along the HIV care continuum.49,50 Among clinics in this study, nine participated in the in+care campaign, suggesting that these resources are frequently but not universally utilized.

Additionally, the comparable outcomes we observed across hospital and community-based clinics may be influenced by the fact that all clinics in our study received RWP funding and interact closely with Department of Public Health. Consequently, clinics are encouraged to track HIV care and outcomes using standardized HRSA HIV/AIDS Bureau performance measures, including retention in care, use of ART, and viral suppression.51 This uniform focus on quality improvement may lead to improved HIV outcomes regardless of clinic setting.52

Consistent with prior research, the presence of clinical pharmacists was strongly associated with the outcome.53–57 One study of 75 patients on ART found improvements in ART adherence, CD4 count and rate of viral suppression following interventions by a clinical pharmacist.53 Another retrospective analysis examining 14,128 patients on ART showed that patients who used HIV-specialized pharmacies were more likely to be adherent to ART than those who visited traditional pharmacies.55 Altogether, pharmacists at various levels of clinical care may improve patient outcomes.

Our study demonstrated significant patient demographic variations by clinic setting, with individuals with low income and public or no health insurance more commonly attending community-based clinics. Most of the community-based clinics in our analysis function as CHCs. Accordingly, the sociodemographics of patients attending community-based clinics are consistent with those seen at CHCs and with their mission.25,27,28,58,59 Members of these traditionally underserved populations have also been shown to have worse HIV outcomes than their counterparts.60,61 In our study, community-based clinics, which were more likely to serve these patient groups, had similar outcomes to hospital-based clinics, demonstrating the utility of the CHC model.

Drivers impacting the selection of one clinic setting over another vary. Patients may select a clinic due to actual or perceived access to specialty services, including mental health and substance abuse treatment. Some CHCs have struggled with providing specialty services to their patients.62,63 Although prior studies have reported that 90% of CHCs have onsite behavioral health services, it is unclear whether this includes comprehensive psychiatric and substance abuse care.63 Clinics that integrate mental health services with HIV care have been reported to have improved ART adherence, decreased high-risk sexual behavior and severity of addiction and increased patient satisfaction.64–66 A recent qualitative study of 212 patients (60% of whom were HIV infected) participating in an integrated primary care and substance abuse program found that patients appreciated the consolidation of services and perceived improvements in their quality of life.66

The current analysis has several limitations. First, this study involved patients receiving care at primarily urban RWP funded clinics in the Philadelphia EMA. While some non-urban clinics were included, the generalizability of results to rural or suburban settings may be limited. Second, data on many potentially relevant services (e.g., care outreach initiatives, co-location of mental health and substance abuse treatment) were not collected. Additionally, we assessed use of ART at the last visit of the year; this definition may underestimate individuals on ART whose regimens were on hold at that time. Third, our sample size precluded an accurate assessment of how academic affiliation or teaching status may have affected the outcome. Fourth, almost all the clinics in the study offered onsite case management; this lack of variability may explain why case management was not associated with the outcome. Lastly, our study was not designed to collect qualitative data.

Improving health outcomes for PLWH requires a multifaceted approach.67,68 Interventions should be targeted not only to patients, but also to clinics and health systems that deliver HIV care. Our study contributes new knowledge on how the setting of care delivery affects clinical outcomes, noting that PLWH seen at either hospital or community-based clinics had a similar likelihood of completing the final three steps of the HIV care continuum. Further studies, including qualitative research, are needed to identify how changes in the health care environment can improve HIV outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the patients, physicians, investigators, and staff involved in the Philadelphia Ryan White System. We would like to acknowledge the staff of the Philadelphia Department of Health AIDS Activities Coordinating Office including Jane Baker, Coleman Terrell, Michael Eberhart, Marlene Matosky, and Ethan Schofer.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (K23-MH097647-01A to BRY).

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors. No official endorsement by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health or the National Institutes of Health is intended or should be inferred.

Author Disclosure Statement

BRY received investigator-initiated research support (to the university of Pennsylvania) and consulting fees from Gilead Sciences.

References

- 1.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, et al. . The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:793–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: HIV prevention through care and treatment–United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:1618–1623 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall HI, Frazier EL, Rhodes P, et al. . Continuum of HIV care: Differences in care and treatment by sex and race/ethnicity in the United States. 2012. Available at: http://pag.aids2012.org/Abstracts.aspx?SID=13&AID=21098 (Last accessed April23, 2014)

- 4.Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, Moore RD, et al. . Establishment, retention, and loss to follow-up in outpatient HIV care. J Acq Immun Def Syndr 2012;60:249–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Althoff KN, Rebeiro P, Brooks JT, et al. . Disparities in the quality of HIV care when using US Department of Health and Human Services indicators. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58:1185–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yehia BR, Fleishman JA, Metlay JP, et al. . Sustained viral suppression in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. JAMA 2012;308:339–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yehia BR, French B, Fleishman JA, et al. . Retention in care is more strongly associated with viral suppression in HIV-infected patients with lower versus higher CD4 counts. J Acq Immun Def Synd 2014;65:333–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dombrowski JC, Kitahata MM, Van Rompaey SE, et al. . High levels of antiretroviral use and viral suppression among persons in HIV care in the United States, 2010. J Acq Immun Def Synd 2013;63:299–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mugavero MJ, Westfall AO, Zinski A, et al. . Measuring retention in HIV care: The elusive gold standard. J Acq Immun Def Synd 2012;61:574–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marks G, Gardner LI, Craw J, et al. . Entry and retention in medical care among HIV-diagnosed persons: A meta-analysis. AIDS 2010;24:2665–2678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Althoff KN, Buchacz K, Hall HI, et al. . U.S. trends in antiretroviral therapy use, HIV RNA plasma viral loads, and CD4 T-lymphocyte cell counts among HIV-infected persons, 2000 to 2008. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:325–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.HIV/AIDS Care Continuum. 2013. Available at: http://aids.gov/federal-resources/policies/care-continuum/ (Last accessed June1, 2014)

- 13.Ulett KB, Willig JH, Lin H-Y, et al. . The therapeutic implications of timely linkage and early retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2009;23:41–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yehia BR, Kangovi S, Frank I. Patients in transition: Avoiding detours on the road to HIV treatment success. AIDS 2013;27:1529–1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eberhart MG, Yehia BR, Hillier A, et al. . Behind the cascade: Analyzing spatial patterns along the HIV care continuum. J Acq Immun Def Synd 2013;64Suppl 1:S42–S51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, Moore RD, et al. . Disparities in receipt of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected adults (2002–2008). Med Care 2012;50:419–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yehia BR, Agwu AL, Schranz A, et al. . Conformity of pediatric/adolescent HIV clinics to the patient-centered medical home care model. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2013;27:272–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yehia BR, Gebo KA, Hicks PB, et al. . Structures of care in the clinics of the HIV Research Network. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2008;22:1007–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tobias CR, Cunningham W, Cabral HD, et al. . Living with HIV but without medical care: Barriers to engagement. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2007;21:426–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giordano TP, White AC, Jr, Sajja P, et al. . Factors associated with the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients newly entering care in an urban clinic. J Acq Immun Def Synd 2003;32:399–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muthulingam D, Chin JM, Hsu L, et al. . Disparities in engagement in care and viral suppression among persons with HIV. J Acq Immun Def Synd 2013;63:112–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall H, Frazier EL, Rhodes P, et al. . DIfferences in human immunodeficiency virus care and treatment among subpopulations in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1337–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor J.NHPF Background Paper: The Fundamentals of Community Health Centers, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pauly G, Jellinek M. Planning a large ambulatory care center at an academic medical center: Economic, political, and cultural issues. J Ambulatory Care Manage 2005;28:182–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dievler A, Giovannini T. Community health centers: Promise and performance. Med Care Res Rev MCRR 1998;55:405–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.About the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. Available at: http://hab.hrsa.gov/abouthab/aboutprogram.html (Last accessed April23, 2014)

- 27.Shi L, Lebrun LA, Tsai J, et al. . Characteristics of ambulatory care patients and services: A comparison of community health centers and physicians' offices. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2010;21:1169–1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forrest CB, Whelan EM. Primary care safety-net delivery sites in the United States: A comparison of community health centers, hospital outpatient departments, and physicians' offices. JAMA 2000;284:2077–2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chu C, Umanski G, Blank A, et al. . HIV-infected patients and treatment outcomes: An equivalence study of community-located, primary care-based HIV treatment versus hospital-based specialty care in the Bronx, New York. AIDS Care 2010;22:1522–1529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gebo KA, Fleishman JA, Conviser R, et al. . Racial and gender disparities in receipt of highly active antiretroviral therapy persist in a multistate sample of HIV patients in 2001. J Acq Immun Def Synd 2005;38:96–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, Moore RD, et al. . Disparities in receipt of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected adults (2002–2008). Med Care 2012;50:419–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yehia BR, Fleishman JA, Agwu AL, et al. . Health insurance coverage for persons in HIV care, 2006–2012. J Acq Immun Def Synd September12014;67:102–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denning P, DeNenno E. Communities in crisis: Is there a generalized HIV epidemic in impoverished urban areas of the United States? 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/other/poverty.html (Last accessed January28, 2014)

- 34.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2013. Available at: http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf (Last accessed January28, 2013)

- 35.Hammer SM, Eron JJ, Reiss P, et al. . Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2008 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. JAMA 2008;300:555–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Hoy JF, et al. . Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2012 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society–USA panel. JAMA 2012;308:387–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States. 2010. Available at: http://aids.gov/federal-resources/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas.pdf (Last accessed April23, 2014)

- 38.Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG, et al. . Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1815–1826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Funk MJ, Fusco JS, Cole SR, et al. . Timing of HAART initiation and clinical outcomes among HIV-1 seroconverters. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1560–1569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stiratelli R, Laird N, Ware JH. Random-effects models for serial observations with binary response. Biometrics 1984;40:961–971 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodger AJ, Lodwick R, Schechter M, et al. . Mortality in well controlled HIV in the continuous antiretroviral therapy arms of the SMART and ESPRIT trials compared with the general population. AIDS 2013;27:973–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arribas JR, Eron J. Advances in antiretroviral therapy. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2013;8:341–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen CJ, Meyers JL, Davis KL. Association between daily antiretroviral pill burden and treatment adherence, hospitalisation risk, and other healthcare utilisation and costs in a US medicaid population with HIV. BMJ Open 2013;3. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berry SA, Fleishman JA, Moore RD, et al. . Trends in reasons for hospitalization in a multisite United States cohort of persons living with HIV, 2001–2008. J Acq Immun Def Synd 1999 2012;59:368–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bangsberg DR, Ragland K, Monk A, et al. . A single tablet regimen is associated with higher adherence and viral suppression than multiple tablet regimens in HIV+ homeless and marginally housed people. AIDS 2010;24:2835–2840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suárez-García I, Sobrino-Vegas P, Tejada A, et al. . Compliance with national guidelines for HIV treatment and its association with mortality and treatment outcome: A study in a Spanish cohort. HIV Med 2014;15:86–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Executive Summary of the in+care Campaign. 2011. Available at: http://www.incarecampaign.org/files/75579/Executive%20Summary.pdf (Last accessed March4, 2014)

- 48.About the Campaign. Incare Campaign. Available at: http://www.incarecampaign.org/index.cfm/75262 (Last accessed March4, 2014)

- 49.Effective Interventions. Available at: http://www.effectiveinterventions.org/en/Home.aspx (Last accessed March4, 2014)

- 50.Resource Center for Prevention with Persons Living with HIV. 2014. Available at: http://www.hivpwp.org/ (Last accessed March4, 2014)

- 51.Data Elements for Client-level Data Export. 2011. Available at: http://hab.hrsa.gov/manageyourgrant/files/2010clientleveldatafields.pdf (Last accessed April15, 2014)

- 52.Keller SC, Yehia BR, Momplaisir FO, et al. . Assessing the overall quality of health care in persons living with HIV in an urban environment. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2014;28:198–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ma A, Chen DM, Chau FM, et al. . Improving adherence and clinical outcomes through an HIV pharmacist's interventions. AIDS Care 2010;22:1189–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saberi P, Dong BJ, Johnson MO, et al. . The impact of HIV clinical pharmacists on HIV treatment outcomes: A systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence 2012;6:297–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murphy P, Cocohoba J, Tang A, et al. . Impact of HIV-specialized pharmacies on adherence and persistence with antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2012;26:526–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horberg MA, Hurley LB, Silverberg MJ, et al. . Effect of clinical pharmacists on utilization of and clinical response to antiretroviral therapy. J Acq Immun Def Synd 2007;44:531–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Henderson KC, Hindman J, Johnson SC, et al. . Assessing the effectiveness of pharmacy-based adherence interventions on antiretroviral adherence in persons with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2011;25:221–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shi LD, Stevens GD. The role of community health centers in delivering primary care to the underserved: Experiences of the uninsured and Medicaid insured. J Ambul Care Manag Qual Manag Meas 2007;30:159–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.United States Health Center Fact Sheet 2011. 2011. Available at: http://www.nachc.com/client//America's%20Health%20Centers%20Fact%20Sheet%20August%202011.pdf (Last accessed July9, 2014)

- 60.Goldstein RB, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Johnson MO, et al. . Insurance coverage, usual source of care, and receipt of clinically indicated care for comorbid conditions among adults living with human immunodeficiency virus. Med Care 2005;43:401–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chu C, Selwyn PA. Current health disparities in HIV/AIDS. AIDS Read 2008;18:144–146, 152–158, C3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cook NL, Hicks LS, O'Malley AJ, et al. . Access to specialty care and medical services in community health centers. Health Aff 2007;26:1459–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neuhausen K, Grumbach K, Bazemore Andrew, et al. . Integrating community health centers into organized delivery systems can improve access to subspecialty care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1708–1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Kalichman MO, et al. . Integrated behavioral intervention to improve HIV/AIDS treatment adherence and reduce HIV transmission. Am J Public Health 2011;101:531–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Proeschold-Bell RJ, Heine A, Pence BW, et al. . A cross-site, comparative effectiveness study of an integrated HIV and substance use treatment program. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2010;24:651–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Drainoni M-L, Farrell C, Sorensen-Alawad A, et al. . Patient perspectives of an integrated program of medical care and substance use treatment. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2014;28:71–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.National HIV Progress Report, 2013. 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies_NationalProgressReport.pdf (Last accessed December13, 2013)

- 68.Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention: Strategic Plan 2011 through 2015. 2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies_DHAP-strategic-plan.pdf (Last accessed June23, 2014)