Abstract

Enzymatic transformation is a fundamental process to control ligand-receptor interactions among proteins for signal transduction in cells. Here we report the first example of enzymatic transformation regulated ligand-receptor interactions of small molecules, in which enzymatic reaction changes the stoichiometry of the ligand-receptor binding from 1:1 to 1:2. We also show that this unique integration of enzymatic transformation and ligand-receptor interactions of small molecules is able to affect the fate of cells.

This communication describes the use of enzymatic reaction to modulate the binding between small molecules. On the cell surface, many receptors carry out signalling functions upon enzymatic transformation. For example, protein kinases and phosphatases catalyze phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of proteins as a key mechanism of immune responses.1 This ubiquitous type of enzyme-associated ligand-receptor interactions of cells illustrates a fundamental feature of live system. Thus it would be of great importance to use small molecules to mimic the essence of this process for controlling the fate of cells. Despite its profound implication, this approach receives little attention and has yet to be explored, largely due to the lack of a proper ligand-receptor system of small molecules.

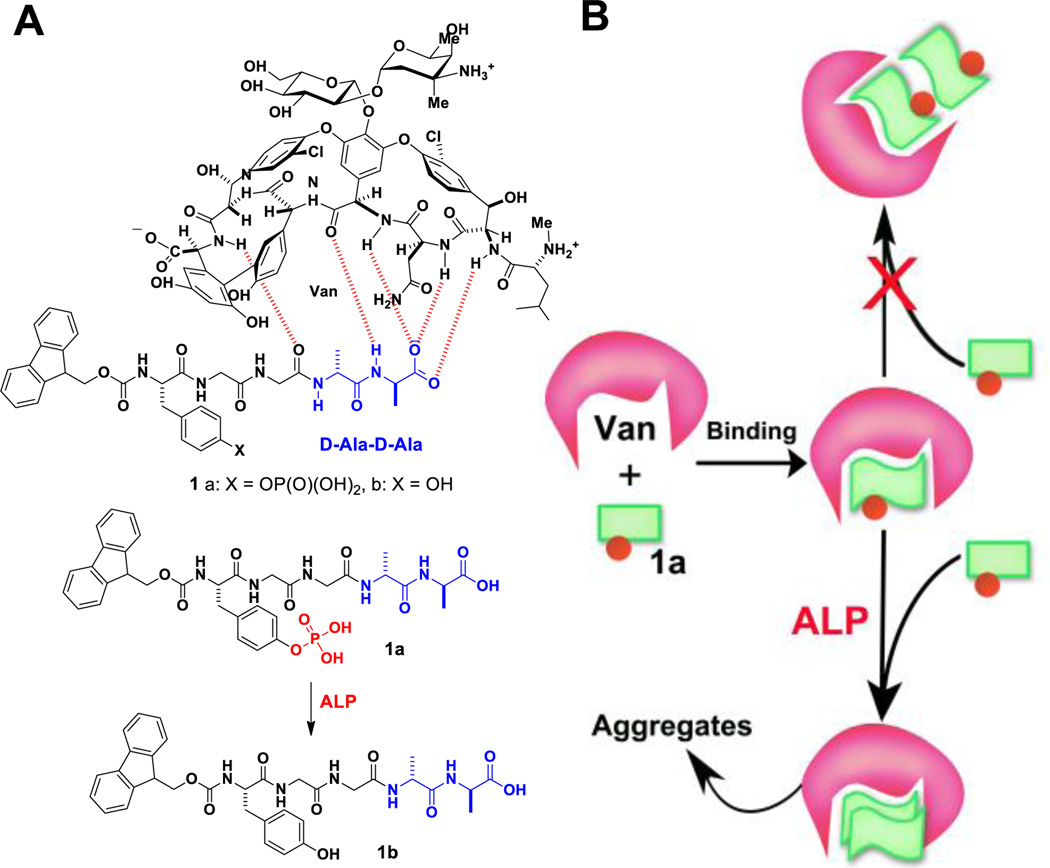

One of well-established ligand-receptor pair of small molecules is vancomycin (Van) and D-Ala-D-Ala. As an important antibiotic to treat methicillin-resistant Gram-positive infections, the ligand-receptor interaction between Van and D-Ala-D-Ala has received extensive investigation, especially in the works of Williams,2, 3 Whitesides,4 as well as other groups.5 Specifically, Van binds with D-Ala-D-Ala via five hydrogen bonds (Fig 1A, upper panel) and can achieve binding in micromolar concentrations. Since the proper N-terminal functionalization confers additional features to D-Ala-D-Ala without seriously compromising the hydrogen bonding between Van and D-Ala-D-Ala, this relatively simple ligand-receptor pair offers a versatile model system to mimic and to control fundamental biological processes. For example, we recently found that Van binds with two Fmoc-D-Ala-D-Ala molecules to catalyze the formation of the aggregates of Fmoc-D-Ala-D-Ala that inhibit cell proliferation.6 Besides offering a reproducible way to generate aggregates of small molecules, this ligand-receptor catalysed aggregation offers a unique opportunity to combine enzymatic transformation, an emerging, powerful approach to control spatiotemporal self-assembly of small molecules,7 with ligand-receptor interactions for achieving specific biological functions.8–10

Figure 1.

(A) The chemical structures of vancomycin and its receptors, derivatives of D-Ala-D-Ala (1a and 1b), 1a is a substrate of phosphatase. (B) Illustration of enzyme transformation to modulate the mode of ligand-receptor binding, to induce the dimerization of the receptors, and to initiate aggregation.

Based on the above rationale, we design molecule 1a (Fmoc-p-Tyr-Gly-Gly-D-Ala-D-Ala) to incorporate an enzyme trigger, tyrosine phosphate, into peptide Fmoc-Gly-Gly-D-Ala-D-Ala. Phosphatase converts 1a to 1b by catalytic dephosphorylation. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) reveals that Van binds with one molecule of 1a, but two molecules of 1b. Moreover, light scattering results show that the use of enzymatic catalysis regulates the ligand-receptor interactions between Van, 1a, and 1b by dephosphorylating 1a to form 1b that binds Van in 2:1 ratio, leading to the formation of the aggregates of Van and 1b (Fig. 1). Moreover, the aggregates generated are able to inhibit cell proliferation. As the first example of enzymatic transformation regulated the ligand-receptor interactions of small molecules, this work illustrates a new approach to mimic the essence of living systems.

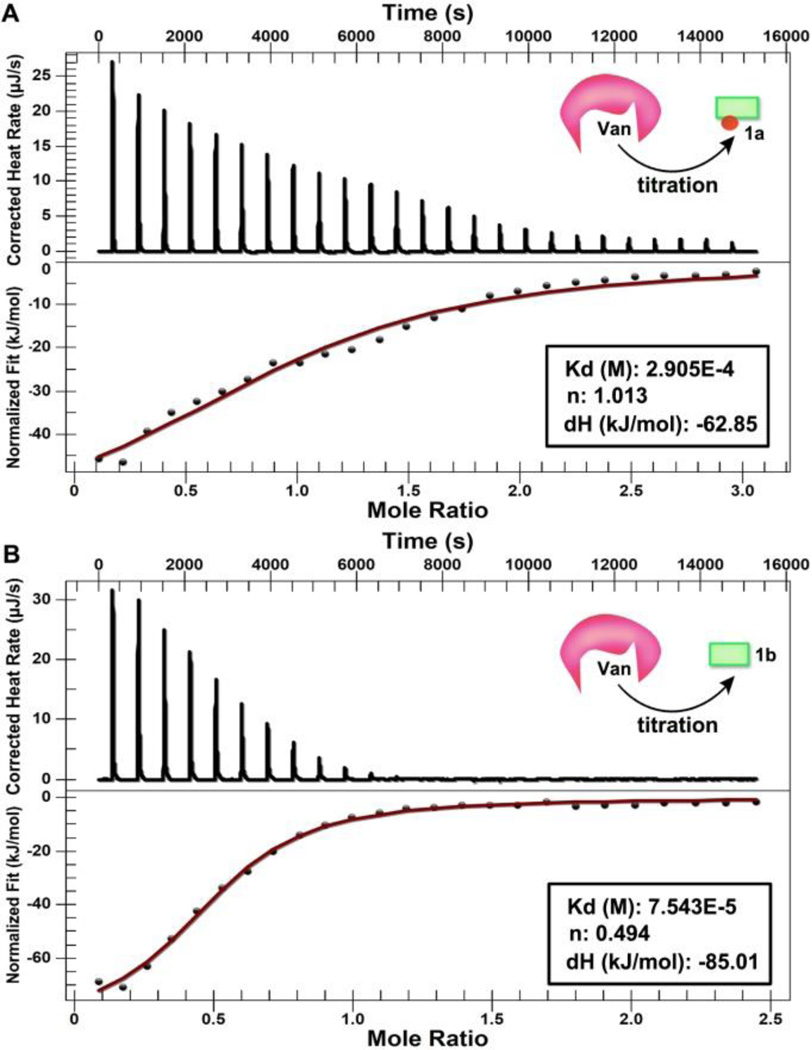

To investigate how Van binds with the D-Ala-D-Ala derivatives (i. e., 1a and 1b), we use isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to examine heating profile during titration. Figure 2A shows the heating flow of each injection during the titration of Van (8.0 mM) into solution of 1a (0.8 mM). After correcting the background dilution and fitting with the independent model, we obtain the dissociation constant (Kd) to be 291 µM and the binding ratio of Van and 1a at 1:1. This result not only agrees with the high affinity between Van and D-Ala-D-Ala,3 but also suggests that one Van binds with one molecule of 1a. ITC indicates that the dissociation constant (Kd) between 1b and Van is 75 µM, and one Van binds with two molecules of 1b. This result implies that the binding affinity between Van and the D-Ala-D-Ala derivatives would increase about four times and the binding stoichiometry would change from 1:1 to 1:2 upon enzymatic dephosphorylation. In other words, these results confirm that enzymatic transformation modulates the ligand-receptor interaction between Van and the D-Ala-D-Ala derivatives. Moreover, such binding likely originates from hydrogen bonding and intermolecular aromatic-aromatic interactions between the fluorene group in 1b, which induces the aggregation of 1b (a plausible mode of interaction in Fig. S1).

Figure 2.

Isothermal titrations of a) 1a, and b) 1b with Van at 25 °C for the determination of dissociation constant (Kd) and stoichiometry (n).

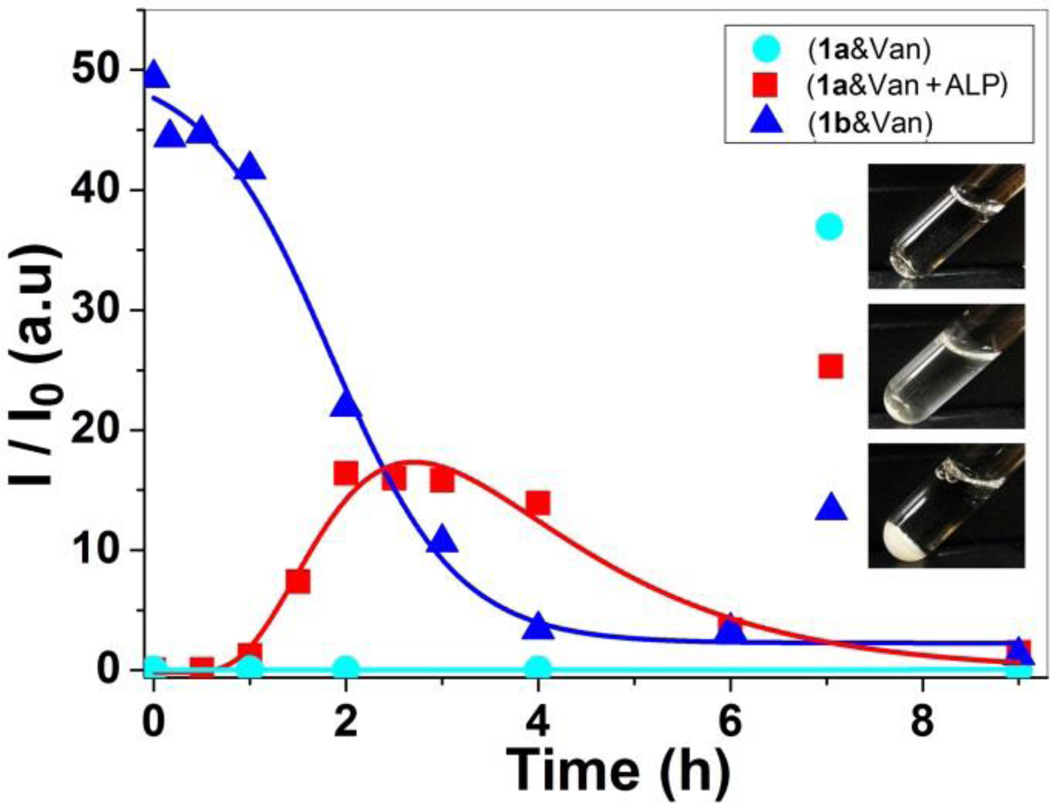

To evaluate the aggregation of 1b regulated by ligand-receptor interaction and enzyme catalysis, we use light scattering to monitor the change of light scattering signal before and after initiating the enzymatic dephosphorylation of 1a in the presence of Van. As shown in Figure 3, the light scattering signal of the solution containing 1a and Van increases gradually in one hour after the addition of alkaline phosphatase (ALP, 0.5 U/mL), then reaches the maximum around 3h, which suggests that, after being produced by the dephosphorylation of 1a, 1b binds with Van to form aggregates. The signal starts decreasing after 3h, accompanied by the observation of micron size aggregates (over 5 µm) (Fig S2). This result agrees with that the large aggregates accumulate to form precipitates, which is consistent with that ALP continues catalysing the transformation of 1a to 1b. As a negative control, we also measure the light scattering signal of the solution containing only 1a and Van (1a&Van) without the addition of ALP. As shown in Figure 3, the solution exhibits negligible signal for over 9h, indicating no detectable aggregates form without the enzymatic formation of 1b. In addition, we also found the solution of 1b even at 500 µM exhibits negligible light scattering signal after 24 h (Shown in Fig. S4), suggesting 1b itself hardly aggregates. As a positive control, we directly mix 1b and Van (1b&Van), the light scattering intensity of the mixture starts with a large signal, continually decreases, and reaches the minimum after 4h, accompanied by the formation of precipitates. This result suggests that mixing 1b and Van immediately results in aggregates, which further cluster to precipitate to the bottom of light-scattering tubes (Inset of Fig. 3). Collectively, these results, unambiguously, demonstrate that enzymatic dephosphorylation of 1a and the subsequent binding between 1b and Van result in the formation of the aggregates. Such difference in light scattering signals before and after the addition of the enzyme further confirms that enzymatic transformation is able to regulate the binding mode between Van and D-Ala-D-Ala derivatives.

Figure 3.

Light scattering intensity (I/I0) as a function of time for the mixtures of 1a and Van (1a&Van), of 1a, Van, and ALP (1a&Van+ALP), and of 1b and Van (1b&Van). Insets are their corresponding optical images after 24 h. [1a]0 = [1b]0 = [Van]0 = 300 µM, ALP is 0.5 U/mL.

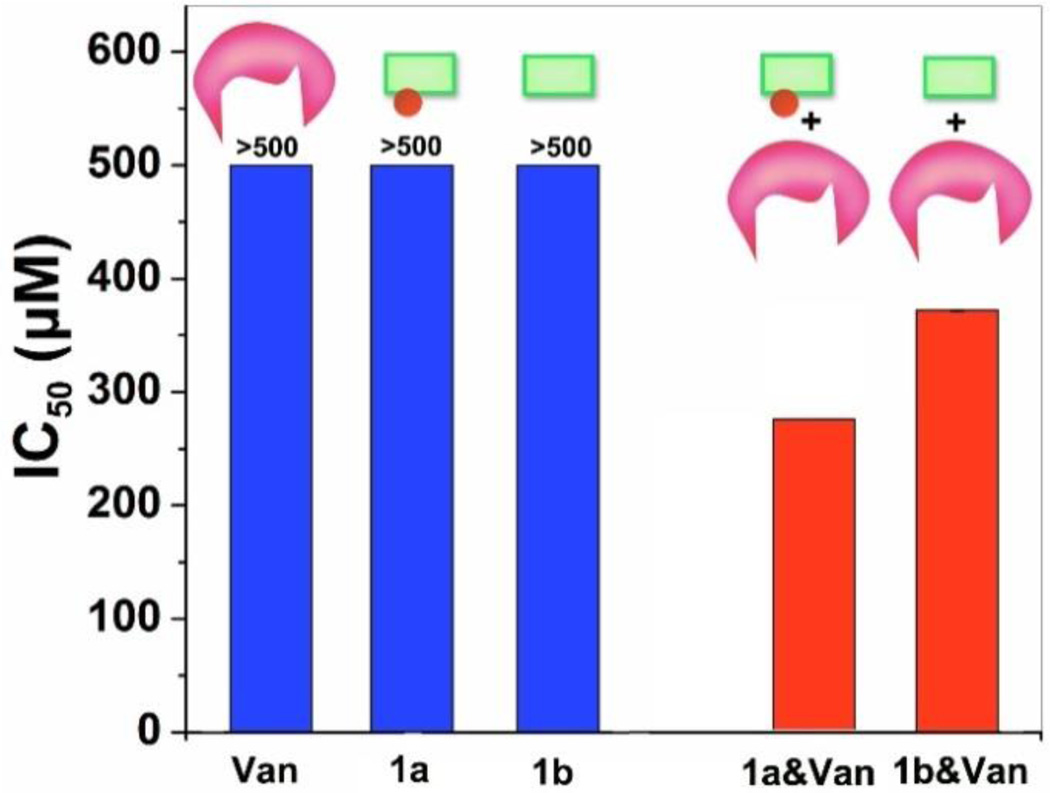

To explore the biological function of aggregates of Van and D-Ala-D-Ala derivatives formed by enzymatic transformation, we use MTT assay to examine the viability of HeLa cells upon treatment with 1a (or 1b), with or without Van. As shown in Figure 4, 1a, 1b, and Van alone is cell compatible even the concentration as high as 500 µM. After mixing with Van at same molar ratio, both 1a and 1b are able to inhibit the cell proliferation, but 1a exhibits higher cytotoxicity than 1b, with IC50 values of 276 µM and 372 µM for 1a and 1b, respectively. Presumably, such differences are associated with the enzymatic transformation of 1a to 1b and subsequent aggregation processes.9 The resulting aggregates 1b&Van likely adhere to cell surface to cause cell death, which is consistent with our recent discovery that the aggregates catalysed by ligand-receptor interaction are able to inhibit the proliferation of cells.6 The lower IC50 of 1a&Van than that of 1b&Van may result from the self-assembly of certain amounts of 1b on cell surface due to the dephosphorylation of 1a.8, 9, 11 In another experiment, after the incubation of HeLa cells with 1a for 12h, the addition of Van at equal molar ratio inhibits HeLa cells proliferation, but IC50 value is slightly higher (385 µM (Fig.S5)) and is comparable to that of the mixture of 1b&Van. Since HeLa cells overexpress ectophosphatases,12 this outcome agrees with that 1b, produced via dephosphorylation of 1a by endogenous phosphatases from the HeLa cells, interacts with Van to form the aggregates that inhibit cell proliferation. These results, thus, indicate that enzyme catalysis and ligand-receptor interaction generate the aggregates for inhibiting the proliferation of the HeLa cells.6

Figure 4.

IC50 values of 1a, 1b, Van and their mixtures against HeLa cell. 1a (or 1b) mixes with Van at same molar ratio, then treated cells immediately. The concentration herein indicated the concentration of individual component.

Conclusions

In summary, this work demonstrates the integration of enzymatic transformation and ligand-receptor interaction of small molecules to control the fate of cells. The spatiotemporal control provided by enzymatic reaction8, 9 and the specificity offered by ligand-receptor interaction should lead a new way to mimic essential functions of living systems for tailoring the formation and the properties of small molecule aggregates13 that are emerging as a new class of biofunctional entities.14

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is partially supported by NIH (R01CA142746), the W.M. Keck Foundation, NSF (DMR-1420382) and fellowships from the Chinese Scholar Council (2008638092 for JFS and 2010638002 for DY).

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.Janeway CA, T P, Jr, Walport M, Shlomchik MJ. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. New York: Garland Science; 2001. [Google Scholar]; Mustelin T, Vang T, Bottini N. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:43. doi: 10.1038/nri1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams DH, Cox JPL, Doig AJ, Gardner M, Gerhard U, Kaye PT, Lal AR, Nicholls IA, Salter CJ, Mitchell RC. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:7020. [Google Scholar]; Westwell MS, Bardsley B, Dancer RJ, Try AC, Williams DH. Chem Commun. 1996:589. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dancer RJ, Try AC, Sharman GJ, Williams DH. Chem Commun. 1996:1445. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao JH, Lahiri J, Isaacs L, Weis RM, Whitesides GM. Science. 1998;280:708. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rao JH, Whitesides GM. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:10286. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park KH, Lee J-S, Park H, Oh E-H, Kim J-M. Chem Commun. 2007:410. doi: 10.1039/b615626f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Choi K-H, Lee H-J, Park BJ, Wang K-K, Shin EP, Park J-C, Kim YK, Oh M-K, Kim Y-R. Chem Commun. 2012;48:4591. doi: 10.1039/c2cc17766h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ulrich S, Dumy P. Chem Commun. 2014;50:5810. doi: 10.1039/c4cc00263f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Leimkuhler C, Chen L, Barrett D, Panzone G, Sun BY, Falcone B, Oberthur M, Donadio S, Walker S, Kahne D. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3250. doi: 10.1021/ja043849e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Xing B, Jiang T, Bi W, Yang Y, Li L, Ma M, Chang C-K, Xu B, Yeow EKL. Chem Commun. 2011;47:1601. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04434b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi J, Du X, Huang Y, Zhou J, Yuan D, Wu D, Zhang Y, Haburcak R, Epstein IR, Xu B. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;137:26. doi: 10.1021/ja5100417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirst AR, Roy S, Arora M, Das AK, Hodson N, Murray P, Marshall S, Javid N, Sefcik J, Boekhoven J, van Esch JH, Santabarbara S, Hunt NT, Ulijn RV. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:1089. doi: 10.1038/nchem.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; de Tullio MB, Castelletto V, Hamley IW, Adami PVM, Morelli L, Castaño EM. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuang Y, Shi J, Li J, Yuan D, Alberti KA, Xu Q, Xu B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:8104. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi J, Du X, Yuan D, Zhou J, Zhou N, Huang Y, Xu B. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:3559. doi: 10.1021/bm5010355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka A, Fukuoka Y, Morimoto Y, Honjo T, Koda D, Goto M, Maruyama T. J Am Chem Soc. 2014 doi: 10.1021/ja510156v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yang Z, Liang G, Guo Z, Guo Z, Xu B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:8216. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gao Y, Shi J, Yuan D, Xu B. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1033. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gouveia RM, Jones RR, Hamley IW, Connon CJ. Biomater. Sci. 2014 doi: 10.1039/c4bm00121d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du X, Zhou J, Wu L, Sun S, Xu B. Bioconj. Chem. 2014;25:2129. doi: 10.1021/bc500516g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pires RA, Abul-Haija YM, Costa DS, Novoa-Carballal R, Reis RL, Ulijn RV, Pashkuleva I. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;137:576. doi: 10.1021/ja5111893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fishman WH, Inglis NR, Green S, Anstiss CL, Gosh NK, Reif AE, Rustigia R, Krant MJ, Stolbach LL. Nature. 1968;219:697. doi: 10.1038/219697a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owen SC, Doak AK, Ganesh AN, Nedyalkova L, McLaughlin CK, Shoichet BK, Shoichet MS. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014;9:777. doi: 10.1021/cb4007584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Feng BY, Toyama BH, Wille H, Colby DW, Collins SR, May BCH, Prusiner SB, Weissman J, Shoichet BK. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:197. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zorn JA, Wille H, Wolan DW, Wells JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19630. doi: 10.1021/ja208350u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kuang Y, Long MJC, Zhou J, Shi JF, Gao Y, Xu C, Hedstrom L, Xu B. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:29208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.600288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Julien O, Kampmann M, Bassik MC, Zorn JA, Venditto VJ, Shimbo K, Agard NJ, Shimada K, Rheingold AL, Stockwell BR, Weissman JS, Wells JA. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:969. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yang Z, Liang G, Xu B. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:315. doi: 10.1021/ar7001914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.