Abstract

There is limited information regarding the use of daptomycin in the neonatal population, and dosage adjustments for neonates with renal dysfunction. We report on the successful use of daptomycin in a 1-month-old, former 24-week gestation neonate with persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE) bacteremia and impaired renal function. We also review the available literature supporting daptomycin use in the neonatal period. Daptomycin peak and trough serum levels were obtained immediately prior to and 60 minutes after the fifth dose. While vancomycin remains the drug of choice for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcal infections, due to increasing reports of treatment failures, alternative therapies are recommended. Based on mounting evidence, daptomycin may be considered an option in persistently bacteremic neonates who fail vancomycin therapy, although further investigation is warranted.

INDEX TERMS: bacteremia, daptomycin, drug monitoring, neonate, pharmacokinetics, Staphylococcus epidermidis

INTRODUCTION

Daptomycin is a lipopeptide antimicrobial agent with Gram-positive coverage, indicated for the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and endocarditis, and complicated skin and skin structure infections in adult patients.1 A single-dose pharmacokinetic evaluation of daptomycin has been completed in infants <120-days-old; however, daptomycin has not been formally evaluated in bacteremic infants.2 We report on the use of daptomycin in a 1-month-old, former 24-week gestation neonate with persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE) bacteremia and impaired renal function. We also summarize the current literature regarding use of daptomycin in the neonatal population.

CASE REPORT

The patient was a 24-week and 1-day-old male infant with a birth weight of 480 gm born via emergent cesarean section due to severe maternal pre-eclampsia and non-reassuring fetal well-being. Maternal history was significant for chronic hypertension with superimposed pre-eclampsia, living related donor renal transplant secondary to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and depression. Maternal baseline serum creatinine (SCr) prior to pregnancy ranged from 0.8 to 1.1 mg/dL, with a maximum SCr of 1.5 mg/dL during pregnancy. On day of life (DOL) 0, the infant was started on ampicillin and gentamicin, and completed a 7-day course for presumed pneumonia. Gentamicin trough levels were drawn to assess drug clearance. Fifty-five hours after his initial gentamicin dose of 5 mg/kg, his gentamicin serum concentration was 2.4 mg/L. Approximately 100 hours after his initial dose, a repeat gentamicin serum concentration was <0.5 mg/L. At birth, his initial SCr was 2.0 mg/dL, with a maximum of 2.3 mg/dL during antibiotic therapy, and minimum of 1.8 mg/dL upon discontinuation. Urine output (UOP) remained reassuring throughout the treatment course. At birth, an umbilical venous catheter and umbilical arterial catheter were placed for central access. On DOL 2, a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) was placed for medication administration and parenteral nutrition delivery. Due to persistently elevated SCr and history of maternal renal dysfunction, a renal ultrasound was obtained on DOL 6. Small-scattered cysts were observed bilaterally, with increased renal cortical echogenicity. On DOL 11, the patient was noted to have calcifications along the capsule of the liver on abdominal ultrasound.

On DOL 12, at a corrected gestational age of 25 weeks and 6 days, the patient developed MRSE bacteremia. At this time, vancomycin was initiated at 15 mg/kg/dose intravenously (IV) every 12 hours. His SCr at this time was 2.7 mg/dL. The organism was susceptible to vancomycin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 2 and ≤ 0.5/9.5, respectively, determined via Microscan. The organism was resistant to cefazolin, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, and nafcillin. Based on susceptibilities, vancomycin was continued. A vancomycin trough serum concentration was obtained prior to the third dose due to intermittent oliguria to assess drug clearance, and was elevated at 33 mg/dL. Vancomycin therapy was subsequently changed to every 48 hours following a repeat vancomycin serum concentration of 17.5 mg/dL, and the infant was maintained on this regimen to achieve serum trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/dL. While receiving vancomycin therapy, the patient's maximum SCr was 3.0 mg/dL. A transthoracic echocardiogram was obtained on DOL 13, significant for a moderate to large patent ductus arteriosus. Repeat peripheral blood cultures were obtained on DOL 14 and 20, and demonstrated late growth of MRSE with a vancomycin MIC = 2. The patient's PICC line was replaced on DOL 20. Subsequent blood cultures were obtained daily (on DOL 21, 22, 23, and 24) and were persistently positive for MRSE despite therapeutic vancomycin serum concentration between 15 and 20 mg/dL.

A repeat transthoracic echocardiogram on DOL 21 was obtained to evaluate for central line thrombus or cardiac vegetations, with no anomalies noted. Due to persistent bacteremia, on DOL 25 at a corrected gestational age of 27 weeks and 5 days, he was started on daptomycin 6 mg/kg per dose IV every 12 hours. The organism was susceptible to daptomycin with an MIC of ≤ 0.5. The infant's SCr upon initiation of therapy was 2.6 mg/dL. Due to case reports of inverse clearance in relation to gestational age, the decision was made not to adjust the drug interval for renal impairment.2,3 Maximum SCr during daptomycin therapy was 2.4 mg/dL, and upon drug discontinuation was 2.1 mg/dL. Follow-up blood cultures drawn on DOL 26, 27, and 33 demonstrated no growth. Abdominal and renal ultrasounds were performed on DOL 26, and showed mild bilateral pelviectasis with no clear infectious foci or abscesses. Head ultrasounds on DOL 19 and 34 did not demonstrate cysts or abscesses.

Daptomycin peak and trough serum concentrations were obtained immediately prior to and 60 minutes after the fifth dose. Daptomycin was detected using an internal standard of ethylparaben and protein precipitation followed by high performance liquid chromatography using methodology developed and validated by Cubist Pharmaceuticals at the Hartford Hospital.4 The serum drug concentration 30 minutes after the end of the 30 minute infusion was 51.9 mg/dL, and the 12-hour trough concentration was 13.5 mg/dL. At the time of sample collection, the infant's blood urea nitrogen and SCr were 82 and 2.3 mg/dL, respectively. Based on manufacturer recommendations, serum creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) levels were monitored throughout the infant's course of therapy, and ranged from 78 U/L at the start of therapy to a maximum of 94 U/L. Upon drug discontinuation, CPK was 71 U/L. The patient received a total of 14 days of daptomycin therapy from the first negative blood culture with concomitant vancomycin therapy due to concern for pneumonia, based on chest radiographs. Prophylactic fluconazole was administered while on antibiotics from DOL 17 to 46, when central venous access was discontinued. No adverse effects were observed during therapy or after completion.

DISCUSSION

We report on the use of daptomycin in a former 24-week neonate with MRSE bacteremia and impaired renal function. Standard adult doses of daptomycin are 6 mg/kg/dose IV every 24 hours for bacteremia, assuming normal renal function. Pharmacokinetic studies in adults demonstrate linear clearance, and produce steady state peak and trough concentrations of 93.9 and 6.7 mg/dL, respectively.1 Pharmacokinetic evaluations of daptomycin clearance in infants less than 120 days old with normal renal function (defined as a SCr < 1.0 mg/dL) receiving single 6 mg/kg doses were observed to be greater than in adults, suggesting that an inverse linear correlation exists between clearance and age.2,3

The majority of case reports in neonates have used doses of 6 mg/kg/dose IV every 12 hours in patients with normal renal function.3,5,6 Serum daptomycin concentrations are not routinely monitored in clinical practice; however, our values were consistent with those from other studies that resulted in successful microbiological clearance. In a case study of a former 23-week, now 2-month-old infant with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia and normal renal function, daptomycin 6 mg/kg/dose IV every 12 hours produced peak and trough levels of 41.7 and 12.7 mg/dL, respectively, and resulted in microbiological clearance.3 In a former 27-week, now 1-month-old infant, the same dose produced lower peak and trough serum concentrations, 27.26 and 11.56 mg/dL, respectively, however, still resulted in blood clearance.5

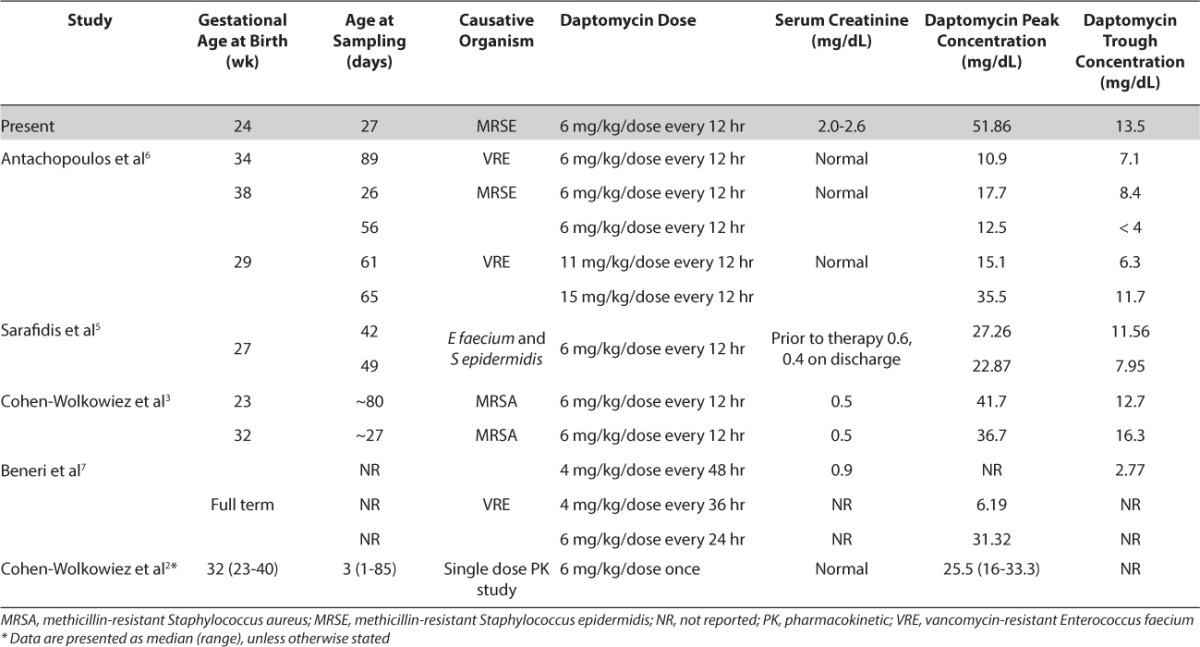

Limited information is available regarding dose adjustments in neonates with renal dysfunction. In adults with impaired renal function (defined as creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min), daptomycin is recommended to be given every 48 hours as it is excreted primarily via the kidneys.1 Beneri et al7 successfully treated a full-term infant with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium bacteremia and impaired renal function using a dose of 6 mg/kg/dose IV every 24 hours, after persistently positive blood cultures while receiving less frequent dosing (including every 36 and 48 hours). In our case, the decision was made not to renally adjust daptomycin due to severity of illness and reported inverse clearance based on gestational age. Serum drug concentrations were similar to those previously reported in the neonatal population, as seen in the Table.2,3,5–7

Table.

No adverse effects were observed in our patient during therapy or after completion. Daptomycin can cause skeletal muscle myopathy with elevations in CPK, and rhabdomyolysis, with or without concomitant acute renal failure. Skeletal myopathies are reversible upon drug discontinuation. In adult patients receiving daptomycin, CPK monitoring is recommended at the start of therapy and at least weekly thereafter. More frequent CPK monitoring is indicated in patients with baseline renal dysfunction.1

While further pharmacokinetic studies in bacteremic neonates are necessary to establish dosing recommendations, based on our experience, daptomycin doses of 6 mg/kg/dose IV every 12 hours appear effective in the treatment of bacteremia, even in the setting of impaired renal function, with no observed toxicities.

Vancomycin remains the drug of choice for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcal infections in adults and neonates; however, there are increasing reports of treatment failures in the adult population, especially in the setting of high vancomycin MICs.8 In neonates with resistant Staphylococcal infections, few alternatives exist, namely daptomycin and linezolid. While linezolid may be useful in alternative sites of infection such as skin and soft tissue infections or pneumonia, it does not have a place in the treatment of Staphylococcal bacteremia.9 Based on mounting evidence, daptomycin appears to be an effective and safe alternative therapy in neonates with resistant infections, although further investigation is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I thank David Nicolau and Christina Sutherland (Hartford Hospital) for their technical assistance.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CPK

creatinine phosphokinase

- DOL

day of life

- IV

intravenously

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- MRSA

methicillin-resistantStaphylococcus aureus

- MRSE

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis

- PICC

peripherally inserted central catheter

- SCr

serum creatinine

- UOP

urine output

Footnotes

Disclosure The author declares no conflicts or financial interest in any product or service mentioned in the manuscript, including grants, equipment, medications, employment, gifts, and honoraria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cubicin® [package insert] Lexington, MA: Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Watt KM, Hornik CP et al. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of single-dose daptomycin in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(9):935–937. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31825d2fa2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Smith PB, Benjamin DK, Jr et al. Daptomycin use in infants: report of two cases with peak and trough drug concentrations. J Perinatol. 2008;28(3):233–234. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dandekar PK, Tessier PR, Williams P et al. Pharmacodynamic profile of daptomycin against Enterococcus species and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a murine thigh infection model. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52(3):405–411. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarafidis K, Iosifidis E, Gikas E et al. Daptomycin use in a neonate: serum level monitoring and outcome. Am J Perinatol. 2010;27(5):421–424. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antachopoulos C, Iosifidis E, Sarafidis K et al. Serum levels of daptomycin in pediatric patients. Infection. 2012;40(4):367–371. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beneri CA, Nicolau DP, Seiden HS, Rubin LG. Successful treatment of a neonate with persistent vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia with a daptomycin-containing regimen. Infect Drug Resist. 2008;1:9–11. doi: 10.2147/idr.s3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rybak MJ, Lomaestro BM, Rotschafer JC et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adults summary of consensus recommendations from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(11):1275–1279. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.11.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corey GR. Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: definitions and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(suppl 4):S254–S259. doi: 10.1086/598186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]