Abstract

We have introduced two disulfide crosslinks into the loop regions on opposite ends of the beta barrel in superfolder green fluorescent protein (GFP) in order to better understand the nature of its folding pathway. When the disulfide on the side opposite the N/C-termini is formed, folding is 2× faster, unfolding is 2000× slower, and the protein is stabilized by 16 kJ/mol. But when the disulfide bond on the side of the termini is formed we see little change in the kinetics and stability. The stabilization upon combining the two crosslinks is approximately additive. When the kinetic effects are broken down into multiple phases, we observe Hammond behavior in the upward shift of the kinetic m-value of unfolding. We use these results in conjunction with structural analysis to assign folding intermediates to two parallel folding pathways. The data are consistent with a view that the two fastest transition states of folding are "barrel closing" steps. The slower of the two phases passes through an intermediate with the barrel opening occurring between strands 7 and 8, while the faster phase opens between 9 and 4. We conclude that disulfide crosslink-induced perturbations in kinetics are useful for mapping the protein folding pathway.

Keywords: kinetics, folding pathway, protein design, leave-one-out GFP

Introduction

Disulfide bonding is the most common post-translational modification. The primary function of disulfide bonds is to bolster stability by crosslinking the backbone. Structural proteins such as α-keratin derive their exceptional strength from a high number of disulfide linkages.1 Proper disulfide formation is also known to be crucial for the function, as demonstrated with ribonuclease A.2,3 Protein disulfide isomerases catalyze the exchange of misformed disulfide bonds necessary for proper function.4 Other disulfide bonds function as redox signaling elements5 for processes such as photosynthesis.6 Disulfide bonds have also been found to regulate the splicing activity of inteins.7

The effect of artificially introduced disulfide crosslinks on protein thermodynamic stability has been explored for several well-studied proteins, including barnase,8 dihydrofolate reductase,9 lysozyme,10 subtilisin,11 factor for inversion stimulation,12 and insulin.13 Surprisingly, both increased and decreased stability have been seen. In theory, an introduced covalent crosslink produces a decrease in the conformational entropy of the unfolded state, thus a decrease in the entropy lost upon folding, shifting the equilibrium towards the folded state. The kinetic effect was quantified by Flory14 and refined by Pace, Grimsley, Thomson & Barnett15 to give the following relation:

| 1 |

Where R is the gas constant and n is the number of amino acids in the chain segment between the participating cysteine residues. The Flory hypothesis is that disulfide bonds which link more sequentially distant residues—a larger n—are more stabilizing. But some engineered mutants of barnase show the opposite trend: the disulfide connecting a shorter loop is more stabilizing.8 Flory's entropic hypothesis14 is not sufficient to explain all observed results,16 and to explain non-Flory behavior, Ramakrishnan17 proposed a folding pathway model for predicting the effects of introduced disulfides that qualitatively accounts for the observed experimental effects. The influence of covalently linking two residues in the chain is seen as a function of the folding order. If those two residues come into contact late in the folding pathway, linking them covalently will slow the unfolding rate because an early step in the unfolding pathway has been blocked. Conversely, if the two residues come together early in folding, then linking them covalently will have little or no effect on the unfolding rate, but may speed up folding by the Flory mechanism. Disulfide-induced misfolding and destabilization of the native state are not modeled by Ramakrishnan.

In this work we explore the usefulness of disulfide engineering in determining the folding pathway of another well-studied protein, green fluorescent protein (GFP). Introduced disulfides are shown to discriminate between alternative theoretical pathways of folding.

In previous work, GFP's fluorescent properties were altered through the use of disulfide engineering for applications as redox sensors. Specifically, a link between position 149 on β strand 7 and position 202 on β strand 10 in yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) caused a fully reversible, redox-sensitive two-fold decrease in the protein's fluorescence. The redox potential was found to be within the range observed for other physiologically relevant proteins. The crystal structure of the mutant shows that the disulfide bond distorts the β-barrel and perturbs the chromophore environment.18 Cysteine mutations closer to the chromophore of wild type GFP have been shown to cause a change in the chromophore's protonation state dependent upon disulfide formation, producing a ratiometric redox-sensitive shift in the excitation spectrum of the protein.19

Recent studies have also shown that stabilization of GFP is possible with disulfide engineering and have extended this mutagenic approach to propose a method for determining the folding order of protein structural elements. The Cycle3 variant of GFP was analyzed using PONDR-FIT, an artificial neural network for the prediction of intrinsically disordered regions of proteins. This analysis suggested that the C-terminus of GFP, the final hairpin of beta strands 10 and 11, has a high degree of disorder and could be stabilized with the introduction of a disulfide bond. The modeled disulfide bond connecting these two beta strands did successfully stabilize the protein, as determined by calorimetry, circular dichroism, and urea gradient gel electrophoresis.20 PONDR-FIT uses primary sequence data and machine learning algorithms to predict intrinsically disordered protein regions; therefore, this approach is unrelated to the hypotheses based on conformational entropy14 and folding pathway.17 Additional disulfide bonds and hydrophobic point mutations produce perturbations in calorimetry-based unfolding kinetics, suggesting a pathway for GFP folding and unfolding.21

The folding pathway of GFP has been studied by simulations and experiment. Mutational analysis has mapped regions of the chain that are sensitive to single residue deletions,22 secondary structure element omission,23 circular permutation,24 and noncircular permutation.25 Strands in the C-terminal half have elevated H/D exchange rates,26 suggesting that they tend to fold last. Molecular dynamics simulations using a simplified representation have identified putative intermediates of folding.27

Here we rationally selected two sites in the loop regions on either end of the GFP barrel near beta strand 7 to introduce cysteine and serine mutations to investigate the effects of disulfide formation on GFP's stability and folding kinetics. All of the mutations introduced appear to have destabilized GFP relative to the wild type protein, but differences in the folding and unfolding kinetics are apparent between reduced and oxidized states. The perturbations caused by the disulfide mutations provide additional insight into folding pathway of GFP.

Results

GFP is an eleven stranded, mostly-antiparallel, closed β barrel surrounding a distorted α helix which contains the chromophore. GFP β strand 7 has been experimentally shown to be disordered in a stable unfolding intermediate, and it was shown that leave-one-out GFP with strand 7 removed (LOO7-GFP) was able to fold to a near-native state.28 Therefore, we suspect strand 7 unfolds early and that restricting its modes of unfolding will kinetically stabilize the protein. Linkages were designed in the loops bordering strand 7, rather than directly between strands, so that the LOO approach could be used to assess the effectiveness of the disulfide engineering in stabilizing a truncated polypeptide chain. The loop regions of GFP were visually assessed in MOE (Chemical Computing Group, Montreal), using superfolder OPT-GFP29 as the template. OPT-GFP is a model derived from the crystal structure of superfolder26 GFP (PDB ID 2B3P). Pairs of amino acids close enough to form disulfide bonds were identified in the proximity of β strand 7. Candidate residues were mutated in silico to cysteine and a disulfide bond was created. The linkage was acceptable if the energy-minimized model had good disulfide geometry and no collisions. Two sites were selected for experimental characterization, called “A” N135C+Q177C and “B” H81C+D197C in this article.

Three constructs were designed: one each with A and B disulfides and one with both, the latter called "AB". Cysteines were mutated to serines to serve as a “constitutively reduced” state. The two native cysteines at positions 48 and 70 were mutated to alanine and threonine respectively to avoid undesired disulfides. Table I summarizes the mutations made in each construct. Figure 1 shows the locations of the disulfides and the local environments of the mutated residues.

Table I.

Mutants and Specific Mutations

| Position | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | 48 | 70 | 81 | 135 | 177 | 197 |

| Wild-type | C | C | H | N | Q | D |

| AB | A | T | C | C | C | C |

| A | A | T | S | C | C | S |

| B | A | T | C | S | S | C |

Cysteine mutations in each construct highlighted in yellow.

Figure 1.

A model derived from the crystal structure of superfolder GFP (PDB:2B3P) showing the locations of the disulfide mutations. The backbone is shown in cartoon, with beta strand 7 shown in red and beta strand 8 shown in green. The modeled disulfides are shown as colored spheres. The A disulfide is highlighted with a red box, and the B disulfide is highlighted with a black box. The close-ups of the highlights show the local environment of the modeled disulfides in stereo.

The A crosslink location connects the β6-β7 loop to the β8-β9 loop. We hypothesized that a link in this position would promote the formation of the β/β strand pairings in the β7-β9 meander. The closing of β7/β8 is one of the suspected slow steps in folding. Indeed, the crosslinked A mutant folds significantly faster. The B crosslink location connects the α-β4 loop with the β9-β10 loop. A link at this position could promote the formation of β/β strand pairings involving the β10-β11 hairpin. The β7/β10 strand pairing was hypothesized to be one of the slow steps in folding.28 Interestingly, the crosslinked B mutant folds marginally slower.

Fluorescence properties

The disulfide mutations do not alter the spectral properties of GFP, but the intensity of the fluorescence is decreased compared to the wild type protein. Induced cultures of BL21(DE3)-derived E. coli cells containing the mutant genes developed green color overnight, indicating that the mutant proteins are capable of catalyzing the maturation of the fluorescent chromophore. Each mutant was purified and the excitation and emission spectra were recorded under reducing and oxidizing conditions (Fig. 2). The excitation and emission maxima of the mutants are not significantly different from the wild type maxima. All three of the mutants show lower fluorescence than wild type GFP in both reducing and oxidizing conditions, but there is significantly less fluorescence in the oxidized state (40–50% of the wild type signal) than in the reduced state (60–70%). This loss in fluorescence upon oxidation of the disulfides can be attributed to distortion of the beta barrel and disruption of the chromophore environment, as previously observed.18,30

Figure 2.

Fluorescence spectra for the disulfide mutants. Excitation scans were from 300 to 495 nm, and emission scans were from 500 to 600 nm. Scans were performed for all three mutants: the AB disulfide (red), the single A disulfide (green) and the single B disulfide (blue) under oxidizing (solid lines) and reducing (dashed lines) conditions. Fluorescence was normalized by protein concentration and plotted relative to the maximum signal of OPT-GFP under the same conditions (black). Under oxidizing conditions, the mutants show about 40–50% of the fluorescence signal of OPT-GFP; under reducing conditions, this number is 60–70%.

Refolding/unfolding kinetics

Unfolding and refolding were performed under reducing and oxidizing conditions for each mutant. Stopped-flow mixing was used to accurately measure the fast phases of refolding while unfolding and the slower phases were captured by manual mixing. All mutants unfolded faster than the wild type protein under reducing conditions. We attribute this to native state destabilization by the six mutated positions. Of interest, however, is not the stability relative to the wild type protein, but the changes in stability, unfolding and folding rates between the reduced and oxidized forms.

To measure the refolding kinetics, the proteins were unfolded overnight in a pH 2.0 buffer, then refolded by rapid dilution into a pH 8.0 buffer while following green fluorescence recovery as a reporter of the native state. Refolding was measured at 20°C in pH8.0 buffer with no denaturant, under oxidizing or reducing conditions. All refolding time courses were found to fit three exponential phases: a fast phase (k1=0.1-0.5 s−1, A1=18–20%), a medium phase, (k2=0.02-0.06 s−1, A2=33–50%), and a slow phase, (k3=0.002-0.009 s−1, A3= 30–48%). The burst phase was negligible (A0=1–2%). The rates (k) agree with previous pH refolding experiments using other GFP variants,28,31 while the amplitudes differ. For OPT-GFP, the fastest rate held more than half of the amplitude.28 Refolding of another mutant (Cycle3) using guanidine dilution reported three phases with rate constants an order of magnitude faster than those reported here.29 The slowest phase of refolding was identified previously as the trans-to-cis peptide bond isomerization at Pro-89 in the unfolded state.31 The existence of two fast phases implies two observable, parallel folding pathways.

The A mutant folds faster under oxidizing conditions. The rates of all three phases are significantly higher when the A disulfide is formed. Mutant B, on the other hand, folds more slowly when the crosslinks are made than when they are not made, but the differences are only marginal. There is a significant increase in the amplitude of the medium phase of folding, suggesting an effect of the B disulfide on the pre-equilibrium distribution of intermediates of folding, favoring the intermediate of the medium phase and/or disfavoring the intermediate of the fast phase. Folding kinetics for the AB mutant do not change appreciably upon oxidation of the two disulfide crosslinks. The reason for the latter may be that the energetic effects of the two disulfides approximately cancel out.

Unfolding was measured by loss of green fluorescence at five different unfolding conditions, varying both guanidine hydrochloride (GuCl) concentration and temperature, all at pH8.0. Kinetic parameters at 20°C and zero denaturant were determined by a log-bilinear extrapolation as described in Methods. Most unfolding time courses were found to fit two exponential phases. Two phases of unfolding were previously observed for Cycle3 GFP.20,21 The highest denaturing condition, 60°C and 6M GuCl, produced single phase data. In contrast to the small variability in the folding rates, the extrapolated unfolding rates varied over several orders of magnitude. All three mutants unfold faster than the parent GFP under reducing conditions. All three mutants unfolded more slowly under oxidizing conditions. We observed disulfide induced changes in the relative amplitudes of the two unfolding phases, their relative rates, and in the kinetic m-value of unfolding.

The entire set of kinetics measurements includes three sets of rates and amplitudes for refolding and two sets of rates and amplitudes for unfolding, for each mutant, and for each condition, comprising a total of 72 measured rates and amplitudes. Six of these measurements, the slow steps of folding for each variant, correspond to an off-pathway event.30 The remaining 66 measurements correspond, in the simplest interpretation, to two on-pathway transition states of folding, representing parallel folding pathways. Perturbations of these rates, amplitudes, and the kinetic m-values inform us about the structural nature of the transition state intermediates along these two pathways (Fig. 3 and Table II).

Figure 3.

Plot of relative amplitudes and rate constants of refolding for the three mutants. This plot shows the kinetic refolding parameters for the AB mutant (black), the single A disulfide mutant (white) and the single B disulfide mutant (gray). The reduced state is plotted with circles, and the oxidized state is plotted with squares. The rate axis is on a logarithmic scale, and the error bars denote ± 1 S.D. in both directions.

Table II.

Kinetic Fits for the (a) Refolding Under Oxidizing and (b) Reducing Conditions, (c) Unfolding Under Oxidizing, and (d) Reducing Conditions

| A0 (%) | A1 (%) | k1 (s−1) | A2 (%) | k2 (s−1) | A3 (%) | k3 (s−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Refolding kinetics at 20°, oxidized | |||||||

| AB | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 17.7 ± 1.8 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 42.5 ± 4.2 | 0.023 ± 0.003 | 38.5 ± 5.4 | 3.5E-3 ± 0.4E-3 |

| A (135–177) | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 17.9 ± 2.3 | 0.58 ± 0.17 | 33.5 ± 9.9 | 0.058 ± 0.026 | 47.9 ± 12.7 | 9.4E-3 ± 1.4E-3 |

| B (81–197) | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 18.9 ± 1.3 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 50.6 ± 4.1 | 0.025 ± 0.002 | 29.7 ± 3.9 | 4.8E-3 ± 0.7E-3 |

| OPT | 2.3 ± 1.3 | 28.2 ± 0.7 | 1.19 ± 0.16 | 38.7 ± 1.4 | 0.072 ± 0.007 | 30.8 ± 2.4 | 7.6E-3 ± 1.5E-3 |

| (b) Refolding kinetics at 20°, reduced. | |||||||

| AB | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 20.7 ± 3.6 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 41.6 ± 5.2 | 0.024 ± 0.004 | 36.3 ± 3.4 | 2.3E-3 ± 0.8E-3 |

| A (135–177) | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 21.1 ± 2.4 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 38.8 ± 4.9 | 0.038 ± 0.007 | 38.5 ± 3.3 | 2.9E-3 ± 0.5E-3 |

| B (81–197) | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 19.1 ± 2.1 | 0.30 ± 0.05 | 40.4 ± 3.4 | 0.032 ± 0.009 | 38.7 ± 2.8 | 3.2E-3 ± 0.3E-3 |

| OPT | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 17.8 ± 0.8 | 1.05 ± 0.13 | 30.3 ± 1.4 | 0.080 ± 0.007 | 50.0 ± 2.4 | 5.7E-3 ± 1.5E-3 |

| A1 (%) | k1 (s−1) | mu1 (kJ M−1) | ln ν1 | ΔG0‡1 | A2 (%) | k2 (s−1) | mu2 (kJ M−1) | ln ν2 | ΔG0‡2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (c) Unfolding kinetics extrapolated from unfolding conditions to 20°, oxidized. | ||||||||||

| AB | 31 ± 4 | 5.6E-4 ± 0.4E-4 | 1.72 | 19 | 6.E4 | 69 ± 15 | 6.9E-5 ± 0.9E-5 | 1.60 | 16 | 6.3E4 |

| A (135–177) | −5 ± 12 | 1.6E-4 ± 0.15E-4 | 2.68 | 19 | 6.7E4 | 105 ± 6 | 5.4E-6 ± 2.1E-6 | 2.86 | 23 | 8.6E4 |

| B (81–197) | −141 ±10 | 4.7E-4 ±0.5E-4 | 1.49 | 17 | 6.0E4 | 241 ±11 | 1.7E-4 ±0.1E-4 | 1.33 | 5 | 3.4E4 |

| (d) Unfolding kinetics extrapolated from unfolding conditions to 20°, reduced. | ||||||||||

| AB | 112 ± 11 | 0.030 ± 0.003 | 0.478 | −3 | 674 | −12 ± 3 | 4.2E-3 ±0.3E-3 | 0.27 | −7 | −4.6E3 |

| A (135–177) | 132 ± 13 | 2.2E-3 ± 0.2E-3 | 1.13 | 8 | 3.5E4 | −32 ± 6 | 5.0E-4 ±2.1E-4 | 1.09 | −1 | 1.6E4 |

| B (81–197) | −6 ± 3 | 0.024 ± 0.001 | 0.670 | −4 | −2.7E3 | 106 ± 8 | 6.9E-5 ±0.7E-5 | 1.39 | 9 | 4.4E4 |

Refolding values reported are the average of triplicate measurements ± 1 S.D. Values in bold are significant at ± 2 S.D or more. Unfolding rates and amplitudes at 25° and 0M GnCl have been extrapolated from unfolding conditions as shown in Supporting Information. Relative errors reported are the averages relative errors of the measurements. Amplitudes in italics, which are outside of the range of 0–100%, are log bi-linear extrapolations from rates and amplitudes under unfolding conditions and are presented only to express qualitative trends. A negative amplitude predicts that the phase will have zero amplitude at 25° and 0M GuCl, an amplitude greater than 100% predicts that the amplitude will be 100%. Values in bold have greater than two standard deviations difference between reduced and oxidized states. OPT refers to the template variant, superfolder OPT GFP.26

Thermodynamic stability

True equilibrium measurements of GFP thermostability are difficult because of its extreme kinetic stability. OPT-GFP has an estimated half-life of unfolding of 161 h in water.30 Cycle3 GFP retains fluorescence for days even in low concentrations of guanidine hydrochloride.32 Because of this, equilibrium stability is calculated here using the ratio of the folding and unfolding rates at 20°C, the latter obtained by extrapolation from unfolding conditions. The results are shown in Table III. Rates kf and ku are the amplitude-weighted average rates.

Table III.

Kinetic and Thermodynamic Values of Folding for the Mutants

| ku (s−1) | kf (s−1) | ΔGf (kJ/mol) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidized | Reduced | Oxidized | Reduced | Oxidized | Reduced | ΔΔGox | |

| AB | 8.14E-5 ± 1.1E-5 | 0.0298 ± 0.003 | 0.038 ± 0.004 | 0.055 ± 0.012 | −15.0 ± 0.45 | −1.49 ± 0.90 | −13.5 |

| A (135–177) | 5.4E-6 ± 0.4E-6 | 2.19E-3 ± 0.2E-3 | 0.129 ± 0.035 | 0.070 ± 0.011 | −24.6 ± 1.55 | −8.46 ± 1.34 | −16.1 |

| B (81–197) | 1.74E-4 ± 0.2E-4 | 6.9E-5 ± 0.2E-5 | 0.045 ± 0.004 | 0.073 ± 0.013 | −13.5 ± 1.23 | −17.0 ± 1.19 | +3.5 |

Values reported are the average of triplicate measurements ± 1 S.D.

The equilibrium stabilities of the three variants are greatly destabilized relative to the parent structure, OPT-GFP. Based on the half-life of unfolding previously reported for OPT-GFP, 161 h, and the weighted average three-phase folding rate (0.2139 s−1), the ΔGf for OPT-GFP is −29.5 kJ/mol. In contrast, the reduced AB mutant is marginally stable at RT, with ΔGf = −1.49 kJ/mol, and the reduced single disulfide mutants are destabilized by 21 and 12.5 kJ/mol for A and B respectively. Changes in the equilibrium stabilities upon oxidation (ΔΔGox) range widely from slightly destabilizing (+3.5 kJ/mol) for the B mutant, to strongly stabilizing (−16.1 kJ/mol) for the A mutant, and the effects appear to be additive. The A mutant is highly stabilized by crosslinking, and the change is mostly the consequence of a 2000-fold decrease in the unfolding rate. The B mutant is slightly destabilized, having a 3-fold faster unfolding rate and a 30% slower folding rate. The AB mutant has the expected additive effect of oxidation. AB folds slower, like B, and unfolds slower, like A. When interpreted in the manner of phi-value analysis,33 we infer that B-disulfide residues 81−197 fold early in the reduced state, while A-disulfide residues 135−177 fold late. A breakdown of the effects on each phase is provided below.

Folding kinetics

Faster folding is expected for a crosslinked protein by way of the Flory effect,14,15 wherein crosslinking positions that are more distant in the chain leads to a greater acceleration of the folding rate via a decrease in the loss of conformational entropy upon folding. However, we saw the greatest acceleration of folding in the A mutant, which crosslinks relatively local positions. The B mutant produced mixed results, with the fast phase rate of folding decreasing and the medium phase not changing significantly. The absence of a clear Flory relationship suggests that the loss of conformational entropy in going from the disordered chain to a native-like state is not the rate limiting step in folding. Instead, a rapid pre-equilibrium leading to a partially folded state must exist. We therefore hypothesize that the folding pathway includes partially folded intermediates.

As a control, OPT-GFP was folded under oxidizing and reducing conditions, showing similar rates of refolding. But surprisingly, the amplitude of the slow phase is significantly increased in the presence of TCEP (Table II). Also, when refolded under oxidizing conditions, OPT-GFP does not recover as much total fluorescence as it does in reducing conditions (data not shown). We may speculate that non-native disulfide formation between normally buried cysteines 47 and 66 could be forming when the pH is raised, leading to a trapped nonfluorescent species.

Unfolding kinetics

To estimate the unfolding rates at 20°C and 0M GuCl we used a log-bilinear extrapolation, fitting the log of the unfolding rate to GuCl concentration and 1/T, as described in Methods. Fast and slow phases of unfolding were fit separately. Supporting Information Figures S1-S6 show the planar fits to the slow and fast phases, along with a planar fit to the amplitude-weighted average rate. The weighted average rates are not expected to fit to a plane, since amplitudes do not appear in the transition state equation and do not depend directly on the energy of the transition state. Indeed, the amplitudes based on the fit to the weighted average rates fall outside the 0–100% range, but the fit is included as a way to illustrate the trend in amplitudes with temperature and denaturant. These trends may be useful in characterizing the structure of the folding intermediates.

The results of log bilinear fitting of the unfolding data are kinetic m-values of unfolding (mu), log transmission coefficients (ln ν), and transition state free energies in water (ΔG0‡), as well as rates (ku) and amplitudes (A). mu measures the dependency of the unfolding rate on denaturant concentration, which may be interpreted as the degree to which the transition state exposes buried surface area. Since we allowed ln ν to vary freely in the curve fitting, the value for the transition state free energy of unfolding in water ΔG0‡ is the part of that free energy that is constant with temperature, in other words, ΔH0‡. Meanwhile, the log of the transmission coefficient, ln ν, should follow transition state entropy of unfolding ΔS‡, which is a measure of the degree to which the transition state is unfolded. With that view, ln ν should parallel mu in its trends, and it does. Because the enthalpy of the transition state ΔH0‡ is roughly proportional to the number of hydrogen bonds broken and the amount of surface exposed, we expect it to correlate with ln ν and mu, and it does. The A disulfide affects both the fast and slow unfolding phases, making them slower and pushing the position of that transition state towards the unfolded state, as evidenced by higher mu, ln ν, and ΔG0‡ values. The B disulfide affects only the fast phase of unfolding, not the slow phase, and shifts the transition state of that phase towards the unfolded state.

Discussion

The thermodynamic effects of disulfide crosslinking

The protein engineering goal of this project was to thermodynamically stabilize a permuted and truncated form of GFP by disulfide crosslinking. In the end, the goal was only half-met. On the one hand, formation of disulfide A clearly increases the kinetic stability of the native (unpermuted) protein, and disulfide B further contributes to this increased stability. On the other hand, disulfide B by itself does not improve kinetic stability. Furthermore, one or more of the six mutations destabilizes the native state, whether in the reduced state or the oxidized state. The results show promise for the stabilization of LOO-GFP by disulfide linkages, but they underscore the need for better algorithms for disulfide design.

The reason for the destabilizing nature of these mutations relative to wild type cannot be ascertained at this time, but we speculatively hypothesize that the cause is topological distortion and frustration of the beta barrel. The loop regions of GFP are tightly packed, and the bulky sulfur atoms of the cysteines may have disrupted packing more than initially predicted, especially in the reduced state, leading to barrel perturbations, core exposure, fluorescence quenching and destabilization. Refolding under oxidizing conditions may have been slowed down relative to wild type because of frustration in forming the beta barrel with the disulfide bond present, particularly the long-range 81–197 disulfide. Position 81 is on the same loop as the cis-proline; attempting to mutate residues or introduce a disulfide bond in this region may cause torsional strain, which would explain the significant perturbations observed in the slow phase of folding. The definitive answer would come from an atomic-resolution crystal structure, but crystallization trials on the mutants to date have been unsuccessful, possibly due to the destabilizing nature of these mutations.

Intermediates of folding

We use disulfide-induced perturbations in kinetic measurements along with structural analysis to propose structures for intermediates along the folding pathway. The justification for the use of kinetic perturbations to characterize the intermediates along a reaction pathway follows Hammond's postulate, which says that the position of the transition state along the reaction pathway shifts toward the higher energy ground state. Observations of Hammond behavior in proteins34 led to the characterization of folding intermediate structures by "phi-value" analysis. In this type of experiment it is assumed that the folding pathway is not changed by the mutation. We observed Hammond behavior in our GFP variants when we saw an upward shift of the m-values and the ΔS‡ of unfolding coinciding with a more thermodynamically stable structure. It makes sense that we assume that the folding pathway is not changed by the disulfide formation, and that instead we are seeing Hammond behavior, specifically the shift of the position of the transition state along the folding pathway.35–37 Figure 4 summarizes the results from kinetic analysis.

Figure 4.

Effects of disulfide bonds on the folding energy landscape. F, folded state; ‡, transition state; I, intermediate states 1 (red) and 2 (blue); U, unfolded state. Red: fast phase. Blue: medium phase. Red arrows indicate changes relative to the reduced state. (a) Native (reduced) landscape. (b) Landscape with the A disulfide present. Folded state is more stable and unfolding is slower. The transition states for both fast and medium phases are shifted towards the unfolded state as shown by the higher m-value. (c) Landscape with the B disulfide present. The medium phase is unaffected by the presence of the disulfide. The fast phase transition state is shifted towards the unfolded state and is faster. (d) Landscape with both A and B present. Both folding and unfolding are slower for both phases and both transition states are shifted towards the unfolded state.

Previous work has set the stage for GFP folding pathway modeling by narrowing the field of possible folding intermediates. GFP and circularly permuted GFPs were shown previously to fold rapidly to nonfluorescent intermediates first, before becoming fluorescent.23 In that work, the solubility of circularly permuted and truncated LOO-GFPs varied widely depending on which β strand was "left out". Increased in vivo solubility was attributed to more efficient folding, and more efficient folding was attributed, in turn, to the completeness of the structure in the absence of a given β strand. Since LOO7-GFP was the most soluble LOO-GFP, we reasoned that the structure of at least one of the intermediates must resemble LOO7-GFP, an open barrel with strand 7 missing.

However, several of the LOO-GFPs were soluble in the absence of one of the strands and were capable of reconstituting the native state fluorescence, corresponding to leaving out strands 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, or 11. Therefore, we propose that the intermediates of folding are open barrels in which a break in the barrel occurs between any of these strands. Others have proposed that the final step in the folding of GFP is a slow “locking” mechanism38 such as the formation of the last row of backbone hydrogen bonds.

We will adopt the term "seam" to refer to a row of contacts between two beta strands. When a seam breaks, the beta barrel opens. There are 11 seams in GFP, implying 11 potential open-barrel intermediates of folding. However, several of these can be eliminated by experimental observation. The N-terminal six strands are known to be sensitive to deletion,23 circular permutation24 and noncircular permutation,25 and are the most hydrophobic strands—all pointing to an early folding intermediate composed of residues 1–133, approximately. On the C-terminal end, strands 3, 7, 8, and 10 have elevated H/D exchange rates,26 and one of the amides between strands 7 and 10 has multiple NMR resonances, suggesting slow conformational exchange.39 Omitting strands 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, or 4 produces a soluble leave-one-out GFP, with LOO7-GFP being dramatically more soluble than the rest. The β7/β8 seam contains the fewest backbone hydrogen bonds.

Supporting Information Figure S7 illustrates the observed energy landscape for GFP, with parallel pathways of folding and two kinetic intermediates. The intermediates are I1 for the fast phase of unfolding, and I2 for the slow phase of unfolding. The correspondence of these two pathways to the fast and medium phases of folding is initially unknown. The off-pathway intermediate of folding is omitted from the landscape for simplicity.

Based on the disulfide induced kinetic perturbations, the residues that form the A disulfide, 135–177, break early in both the fast and the slow pathways of unfolding. Structural analysis suggests that breaks at β7/β8, β8/β9, or β9/β4 would cause residues 135 and 177 to separate spatially. A break in the barrel at β10/β7, β10/β11 or β11/β3 would not lead to structural changes at 135–177. We can therefore rule out the latter as possible intermediates, even though one of these, β10/β7, was previously proposed25 as an intermediate based on the kinetic analysis of a "re-wired" GFP.

Borrowing from Flory, we can state that the A disulfide would increase the rate of barrel closure if the break is the β7/β8 or the β9/β4 seam, since the contact order is made shorter by the disulfide. For β7/β8, the disulfide occurs on the side opposite the main chain connection, and thus decreases the contact order on one side of that seam. For β9/β4, the native contact order is very high, and a bridge between β6 and β9 creates a cycle. Seams β4/β5 and β5/β6 already have a small contact order and have been ruled out based on low LOO-GFP in vivo solubility.23 For β8/β9, the disulfide occurs on the same side of the barrel as the hairpin turn and thus does not decrease the effective contact order. The oxidation of the A mutant increases both folding rates significantly. We therefore conclude that the two intermediates I1 and I2 must be the closing of seams β7/β8 and β9/β4.

Structural analysis suggests that the residues in the B disulfide, 81–197, are separated or otherwise strained by the opening of the barrel at seams β4/β9, β3/β11, or β10/β11, but not by seams β7/β8, β8/β9, or β7/β10. This identifies β4/β9 as the fast unfolding phase intermediate, I1, since only the fast rate of unfolding is affected by oxidation of the B disulfide. The slow unfolding phase intermediate, I2, must be β7/β8.

A rational analysis of the structure helps to explain why these two seams, and not the nine others, are observed in the intermediates of folding. β4/β9 is the only seam with high contact order that is also relatively hydrophilic, with a inwardly pointing sidechain composition that is 6/9 polar, including an arginine. β8/β9 is much more hydrophobic and has a low contact order, both factors which would lead to faster folding. β3/β11, β1/β6, and β7/β10 also have high contact orders, but these seams are much more hydrophobic. β7/β10 has 9 inward pointing sidechains, of which three are polar, two threonines and a tyrosine. β7/β8 has the fewest backbone hydrogen bonds—4, where all other seams have at least 6—and hydrogen bonding does not extend the length of the barrel, making it a weaker seam and a likely candidate for an early unfolding step, despite having a low contact order.

The effect of disulfides on the slow phase of folding

The slow phase of folding is accelerated in the oxidized state for all mutants, A, B, and AB. The slow phase is an off-pathway cis/trans isomerization of the backbone at proline 89.30 Its acceleration by the crosslinking of 81–197 and/or 135–177 says that the nature of the unfolded state has been changed to reduce the barrier for backbone isomerization. A relative destabilization of the non-native state is not surprising, since we expected the covalent enforcement of native contacts to favor the native state over all other states.

GFP and GeoFold

GeoFold is a program that predicts the unfolding pathways of proteins and simulates unfolding kinetics.17 GeoFold unfolding pathways successfully predicted the effects of engineered disulfides in barnase, lysozyme, dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), and factor for inversion stimulation (FIS). None of these structures is a beta barrel, like GFP. The barrel structure of GFP revealed a shortcoming in the GeoFold algorithm's move set: it does not produce realistic unfolding pathways for barrel-like proteins, because a barrel opening cannot be constructed from GeoFold's "break, hinge and pivot" methodology. A new move must be developed to identify “seams” and to find possible seam moves in barrel proteins. A seam does not split the protein into two substructures but only breaks a set of contacts. Work is in progress to correct this shortcoming.

Comparison with other GFP folding pathway models

Kuwajima first described the structural characteristics of the GFP folding pathway using data from green and tryptophan fluorescence and circular dichroism.31 Their data converged on the opening of the β7/β8 seam as the likely first step in unfolding, citing also H/D exchange and rational structural analysis. This agrees with our model.

Melnik21 applied disulfide engineering and hydrophobic substitutions to GFP, and proposed a folding pathway based on changes in heat denaturation kinetics, measured using differential scanning microcalorimetry and fluorescence. Two phases were observed, as we observed for our variants. But Melnik fit the data to two sequential intermediates of unfolding, whereas we fit the data to two parallel intermediates. Unless the first sequential step is a slow pre-equilibrium between two folded states before thermal denaturation, any sequential two step reaction will show only the slower of the two steps. Parallel pathways split the population of the folded state and give two observed rates. In their resulting pathway, the first unfolding step was judged to be the separation of the β4/β5 hairpin. Although this conflicts with our model, it is spatially very close to our proposed fast phase of unfolding located at seam β4/β9. The perturbations observed by Melnik could have been the result of the β4 mutation on the β4/β9 seam.

Melnik also observed that perturbations in the Arrhenius dependence of ln(ku) on 1/T, which marks enthalpic changes, were dispersed over the whole protein, and asked in that paper "Why do changes occur specifically in the enthalpic component of the energy barrier?" Here we see agreement with our model and can offer an answer for this question. The barrel opening step that we have proposed does not increase the degrees of conformational freedom of the protein backbone, but it does change the overall shape. After barrel opening, all residues remain hydrogen bonded or otherwise packed and are not free to rotate around backbone bonds. But hydrogen bonds are broken, contributing to the enthalpic component. And the overall change of shape from a barrel to an open barrel would lead to widespread changes in side chain packing, also a mostly enthalpic component.

Thirumalai27 used coarse-grained molecular simulations to fold a chromophore-less variant of GFP, and found several possible intermediate structures in which supersecondary structural units were formed. The longest-lasting partially folded intermediate in those simulations had strands 1–6 and helix in one domain, and the C-terminal strands 7–11 in another. This result agrees with our proposed β4/β9 open seam intermediate, but in none of those simulations did they observe a break at β7/β8, as we have proposed.

It is exciting to see a convergence of observations and views on GFP folding pathways, made especially significant by the diversity of methods used.

Materials and Methods

Gene synthesis and cloning

Oligonucleotides (IDT DNA) for whole gene synthesis by fragment assembly PCR40 were designed using DNAWorks.41 The oligonucleotide length was set to 60 and the desired melting temperature was set to 62°C. Assembly PCR was carried out using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Finnzymes). The 5' and 3' terminal fragments were designed with NcoI and EcoRI restriction enzyme cut sites, respectively, for use in cloning. The assembled genes were cloned into the pET28a plasmid (Novagen) using standard molecular biology techniques. The fidelity of the genes was confirmed by sequencing (MCLab).

Protein expression and purification

Acella E. coli cells (EdgeBio) containing the plasmids were grown to OD600 0.4 at 37°C with shaking. At this point, IPTG was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM and expression was allowed to run for at least 16 h at 25°C with shaking. After expression, the cells were lysed using sonication. The protein was purified from the soluble fraction of the lysate using two-phase organic extraction as described previously.42 The protein was further polished with medium-pressure size-exclusion chromatography on a BioLogic DuoFlow FPLC system (Bio-Rad) with a Tricorn 10/300 Superose 12 column (GE Healthcare) and quantified using the BCA assay (Pierce).

Disulfide bond formation

To confirm spontaneous air oxidation of disulfide bonds, Ellman's reagent was used to assay for unreacted cysteine thiols. A standard curve was generated using l-cysteine, and the final concentration of protein was 10 µM. Absorbance was measured at 412 nm with a UV-1650PC spectrophotometer (Shimadzu). Since the GFP chromophore absorbs at this wavelength, a sample of protein without Ellman's reagent was measured to obtain a baseline absorbance. In order to ensure that free thiols were accessible, the proteins were unfolded using a pH jump and detergent. Stepwise dilution was performed with a dilution of protein to 100 µM in pH 2.0 phosphate buffer (100 mM sodium phosphate, 1 mM EDTA, 2% SDS), followed by dilution to 10 μM in pH 8.0 phosphate buffer (100 mM sodium phosphate, 1 mM EDTA, 2% SDS). The second pH jump was necessary because Ellman's reagent reacts through a thiol-exchange mechanism which requires the free thiol to be deprotonated. The SDS keeps the protein unfolded and the thiols accessible once the pH is returned to 8.

Fluorescence properties

Excitation and emission spectra were recorded for each mutant on a Fluorolog Tau-3 fluorometer operating in steady-state mode (Horiba Jobin-Yvon). The final concentration of protein for each measurement was 0.1 µM, and the slit widths were 1 nm/3 nm for excitation and emission, respectively. For emission, the excitation wavelength was set to 485 nm and emission wavelengths were scanned from 500 to 600 nm in 0.3 nm increments with an integration time of 0.3 s. For excitation, the emission wavelength was set to 508 nm and excitation wavelengths were scanned from 300 to 495 nm with the same scan settings.

Refolding kinetics

Stopped-flow mixing was performed with an SFM-400 mixer (BioLogic) attached to a J-815 spectropolarimeter (Jasco) measuring right-angle fluorescence. The excitation wavelength was set to 485 nm, the bandpass was set to 10 nm, sensitivity was set to high, a 495 nm emission filter was used, and the photomultiplier tube voltage was set to 500 V. The protein was unfolded at a concentration of 0.8 mg/mL in 50 mM phosphate, 100 mM NaCl, pH 2.0 buffer with and without 1 mM TCEP and allowed to equilibrate overnight. Refolding was initiated by the mixer using a 1 : 10 dilution of unfolded protein with 50 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.0 buffer with and without 1 mM TCEP. The mixing ratio of the syringes was set to 5 : 5 : 0 : 1 to minimize instrument dead time (∼2.4 ms). Refolding was measured every 0.1 s for 45 s.

The proteins were refolded at room temperature (20°C) using a pH jump, and the recovery of fluorescence was measured with both manual mixing and stopped-flow mixing. Manual mixing was performed on a Fluorolog Tau-3 fluorometer operating in steady-state mode (Horiba Jobin-Yvon) with excitation and emission wavelengths set to 485 and 508 nm, respectively, integration time set to 0.3 seconds, and slit widths at 1 nm/3 nm for excitation and emission, respectively. The protein was unfolded at a concentration of 1 µM in 50 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM NaCl, pH 2.0 buffer with and without reducing agent, 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), allowed to equilibrate overnight, and diluted 1 : 10 into 50 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.0 buffer with and without 1 mM TCEP at the time of measuring. Refolding was measured every second for a total time of 20 min.

The refolding traces were fit to multiple exponentials of the general form:

| 2 |

Where t is time, F(t) is the fluorescence at time t, is the amplitude of the burst phase of refolding with rates too fast to measure, and

is the amplitude of the burst phase of refolding with rates too fast to measure, and and

and are the amplitudes and rate constants, respectively, of the n measured phases of refolding. Curve fitting was done by minimizing the sum of squared residuals (SSR) using the Microsoft Excel SOLVER add-in. The stopped-flow data and the manual mixing data were fit simultaneously; a scaling factor was added to the stopped-flow data and was included as a fitting parameter. One-phase (n = 1) through four-phase (n = 4) exponentials were tested, and three-phase fits were found to match the data best, showing the best reduction in the SSR and a low autocorrelation value for the residuals. All kinetics measurements were done in triplicate.

are the amplitudes and rate constants, respectively, of the n measured phases of refolding. Curve fitting was done by minimizing the sum of squared residuals (SSR) using the Microsoft Excel SOLVER add-in. The stopped-flow data and the manual mixing data were fit simultaneously; a scaling factor was added to the stopped-flow data and was included as a fitting parameter. One-phase (n = 1) through four-phase (n = 4) exponentials were tested, and three-phase fits were found to match the data best, showing the best reduction in the SSR and a low autocorrelation value for the residuals. All kinetics measurements were done in triplicate.

Unfolding kinetics

The proteins were unfolded by 1 : 100 dilution into a stirred, heated cuvette containing various concentrations of GuCl in pH 8.0 buffer (25 mM sodium phosphate, 25 mM NaCl, with and without 1 mM TCEP). Loss of fluorescence was measured over time on a Fluorolog Tau-3 fluorometer operating in steady state mode (Horiba Jobin-Yvon) with excitation and emission wavelengths set to 485 and 508 nm, respectively, integration time set to 0.3 seconds, and slit widths at 1 nm/3 nm for excitation and emission, respectively. The final concentration of protein was 0.1 µM. Conditions used were: 40°, 4M GuCl; 40°, 6M GuCl; 60°, 4M GuCl; 60°, 6M GuCl; 80°, 0M GuCl. Unfolding was measured every 0.5 s for 450 s.

The unfolding traces were fit to multiple exponentials of the general form:

| 3 |

Where t is time, F(t) is the fluorescence at time t, A∞ is the fluorescence at equilibrium, and and

and are the amplitudes and rate constants, respectively, of the measured phases of unfolding. Curve fitting was done by minimizing the sum of squared residuals (SSR) using the Microsoft Excel SOLVER add-in. A∞ was included as a fitting parameter. One-phase (n = 1) through four-phase (n = 4) exponentials were tested, and the number of phases which best fit varied between one and three.

are the amplitudes and rate constants, respectively, of the measured phases of unfolding. Curve fitting was done by minimizing the sum of squared residuals (SSR) using the Microsoft Excel SOLVER add-in. A∞ was included as a fitting parameter. One-phase (n = 1) through four-phase (n = 4) exponentials were tested, and the number of phases which best fit varied between one and three.

Calculation of thermodynamic stability

The thermodynamics stabilities ΔGf for each mutant were determined as the log of the ratio of the refolding and unfolding rates at room temperature in water, -RT ln(kf/ku). The refolding rate constant kf for the two-state model was computed from the kinetic fits by taking the derivative of the fit equation at time zero and normalizing by the sum of the amplitudes:

| 4 |

Initial unfolding rates ku for each of the unfolding conditions were computed from the multi-phase kinetic fits as described above for kf, by using the amplitude-weighted sum of rates. The parameters for calculating the initial unfolding rate constant ku at room temperature in water were found by fitting each unfolding phase, separately, of the following equation:

| 5 |

Where ν is the transmission coefficient or the prefactor,43 [GuCl] is the molarity of guanidine hydrochloride, is the free energy of the transition state of unfolding in water, mu is the kinetic m-value of unfolding, R is the gas constant, and T is the temperature in Kelvin. This equation assumes that the log of the unfolding rate has a linear relationship with [GuCl] and with 1/T, the Arrhenius relationship. Protein folding kinetics frequently violates the Arrhenius relationship,44 especially when the kinetics are multiphasic. However, in this case we did find an approximately log-linear relationship of unfolding rate with 1/T.

is the free energy of the transition state of unfolding in water, mu is the kinetic m-value of unfolding, R is the gas constant, and T is the temperature in Kelvin. This equation assumes that the log of the unfolding rate has a linear relationship with [GuCl] and with 1/T, the Arrhenius relationship. Protein folding kinetics frequently violates the Arrhenius relationship,44 especially when the kinetics are multiphasic. However, in this case we did find an approximately log-linear relationship of unfolding rate with 1/T.

Values for ln(ν), mu and were obtained by minimizing the sum of squared residuals (SSR) using the Microsoft Excel SOLVER add-in. These values were used to extrapolate the ku equation to 20°C and 0M guanidine. Relative error ranges were estimated as the averages of the relative error ranges of the extrapolated data points, each of which consists of the parameters of a least-squares fit to an unfolding trajectory, done in triplicate.

were obtained by minimizing the sum of squared residuals (SSR) using the Microsoft Excel SOLVER add-in. These values were used to extrapolate the ku equation to 20°C and 0M guanidine. Relative error ranges were estimated as the averages of the relative error ranges of the extrapolated data points, each of which consists of the parameters of a least-squares fit to an unfolding trajectory, done in triplicate.

Since most of the data points were well fit by two kinetic phases, we fit the fast and slow phase rates separately to Eq. 5 and extrapolated fast and slow rates (ku1, ku2) of unfolding at 20°C in water. The complete rate equation for biphasic kinetics requires relative amplitudes of the two phases, but these could not be determined by log-bilinear extrapolation since they do not appear in Eq. 5. Instead, we fit the amplitude weighted average unfolding rates [like Eq. 4, but for unfolding data] to the log-bilinear equation [Eq. 5] and generated one value for ku at 20° in water. We observed that ku was sometimes outside of the range (ku1, ku2) and therefore could not be the weighted average of those two rates. We tentatively attribute the non-Arrhenius behavior of the weighted average rates to the effects of GuCl and T on the concentration of fast pre-equilibrium states of unfolding that define the phase amplitudes. Here we chose to assign ku at 20°C in water to the value of ku1 if ku > ku1, or ku2 if ku < ku2. These are the unfolding rates that were used to calculate ΔGf.

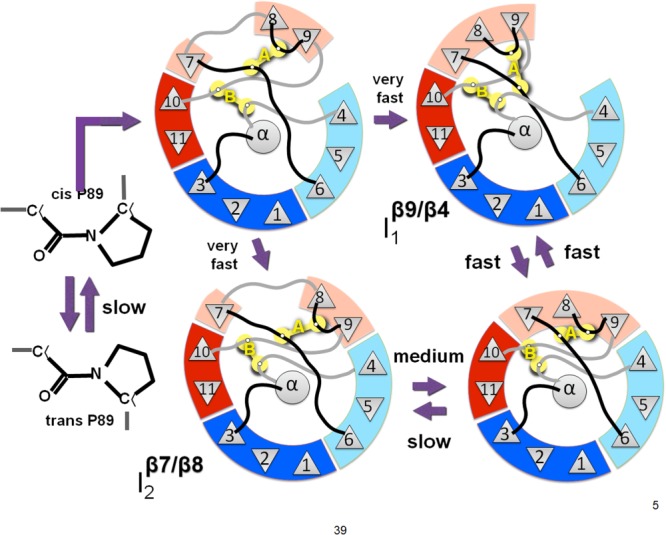

Conclusions

We conclude that the folding pathway of GFP has an off-pathway peptide backbone isomerization event30 and two parallel pathways passing through open barrel intermediates. Unfolding passes through the same two open barrel intermediates. The fast phase of folding and unfolding is a barrel open at the β4/β9 seam, and the slow phase of unfolding, medium phase of folding, is a barrel open at the β7/β8 seam, as shown in Figure 5. Disulfide engineering greatly increased the kinetic stability of GFP relative to the reduced state, but destabilized the native state relative to the parent protein. The results show how disulfide engineering, combined with multiphase folding/unfolding kinetics can help structurally define the folding pathway.

Figure 5.

Proposed barrel-closing intermediates. The fast phase intermediate I1 has a break in the barrel between strands 9 and 4. The medium phase intermediate I2 has a break in the barrel between strands 7 and 8. An unstable intermediate may exist in which both of the barrel breaks are present. The slow phase is the isomerization of the backbone at proline 89 producing an off-pathway intermediate in the unfolded state.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Marimar Lopez and the RPI Analytical Biochemistry Core for assistance with instrumentation and experimental design. They thank Prof. Steven Cramer, Dr. Yao-Ming Huang and the members of the Bystroff and Cramer labs for helpful discussions.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

References

- Jones LN, Simon M, Watts NR, Booy FP, Steven AC, Parry DAD. Intermediate filament structure: hard α-keratin. Biophys Chem. 1997;68:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(97)00013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anfinsen CB. Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science. 1973;181:223–230. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4096.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruoppolo M, Vinci F, Klink TA, Raines RT, Marino G. Contribution of individual disulfide bonds to the oxidative folding of Ribonuclease A. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12033–12042. doi: 10.1021/bi001044n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson B, Gilbert HF. Protein disulfide isomerase. Biochim Biophys Acta, Proteins Proteomics. 2004;1699:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren A. Thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13963–13966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cséke C, Buchanan BB. Regulation of the formation and utilization of photosynthate in leaves. Biochim Biophys Acta, Rev Bioenerg. 1986;853:43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Li L, Du Z, Liu J, Reitter JN, Mills KV, Linhardt RJ, Wang C. Intramolecular disulfide bond between catalytic cysteines in an intein precursor. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:2500–2503. doi: 10.1021/ja211010g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J, Fersht AR. Engineered disulfide bonds as probes of the folding pathway of barnase: increasing the stability of proteins against the rate of denaturation. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4322–4329. doi: 10.1021/bi00067a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villafranca JE, Howell EE, Oatley SJ, Nguyen Huu X, Kraut J. An engineered disulfide bond in dihydrofolate reductase. Biochemistry. 1987;26:2182–2189. doi: 10.1021/bi00382a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura M, Signor G, Matthews BW. Substantial increase of protein stability by multiple disulphide bonds. Nature. 1989;342:291–293. doi: 10.1038/342291a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JA, Powers DB. In vivo formation and stability of engineered disulfide bonds in subtilisin. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:6564–6570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhold D, Beach M, Shao YP, Osuna R, Colon W. The location of an engineered inter-subunit disulfide bond in factor for inversion stimulation (FIS) affects the denaturation pathway and cooperativity. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9767–9777. doi: 10.1021/bi060672n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinther TN, Norrman M, Ribel U, Huus K, Schlein M, Steensgaard DB, Pedersen TÅ, Pettersson I, Ludvigsen S, Kjeldsen T, Jensen KJ, Hubálek Fe. Insulin analog with additional disulfide bond has increased stability and preserved activity. Protein Sci. 2013;22:296–305. doi: 10.1002/pro.2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory PJ. Theory of elastic mechanisms in fibrous proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 1956;78:5222–5234. [Google Scholar]

- Pace CN, Grimsley GR, Thomson JA, Barnett BJ. Conformational stability and activity of ribonuclease-t1 with zero, one, and 2 intact disulfide bonds. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:11820–11825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz SF. Disulfide bonds and the stability of globular proteins. Protein Sci. 1993;2:1551–1558. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560021002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan V, Srinivasan SP, Salem SM, Matthews SJ, Colón W, Zaki M, Bystroff C. Geofold: topology-based protein unfolding pathways capture the effects of engineered disulfides on kinetic stability. Proteins. 2012;80:920–934. doi: 10.1002/prot.23249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard H, Henriksen A, Hansen FG, Winther JR. Shedding light on disulfide bond formation: engineering a redox switch in green fluorescent protein. EMBO J. 2001;20:5853–5862. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.5853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AJ, Dick TP. Fluorescent protein-based redox probes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:621–650. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnik BS, Povarnitsyna TV, Glukhov AS, Melnik TN, Uversky VN. SS-stabilizing proteins rationally: intrinsic disorder-based design of stabilizing disulphide bridges in GFP. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2012;29:815–824. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2012.10507414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnik TN, Povarnitsyna TV, Glukhov AS, Melnik BS. Multi-state proteins: approach allowing experimental determination of the formation order of structure elements in the green fluorescent protein. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e48604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpino JA, Rizkallah PJ, Jones DD. Structural and dynamic changes associated with beneficial engineered single-amino-acid deletion mutations in enhanced green fluorescent protein. Acta Cryst. 2014;D70:2152–2162. doi: 10.1107/S139900471401267X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y-m, Nayak S, Bystroff C. Quantitative in vivo solubility and reconstitution of truncated circular permutants of green fluorescent protein. Protein Sci. 2011;20:1775–1780. doi: 10.1002/pro.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. Circular permutation and receptor insertion within green fluorescent proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11241–11246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder PJ, Huang Y-M, Dordick JS, Bystroff C. A rewired green fluorescent protein: folding and function in a nonsequential, noncircular GFP permutant. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10773–10779. doi: 10.1021/bi100975z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabantous S, Terwilliger TC, Waldo GS. Protein tagging and detection with engineered self-assembling fragments of green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotech. 2005;23:102–107. doi: 10.1038/nbt1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy G, Liu Z, Thirumalai D. Denaturant-dependent folding of GFP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:17832–17838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201808109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y-M, Bystroff C. Complementation and reconstitution of fluorescence from circularly permuted and truncated green fluorescent protein. Biochemistry. 2009;48:929–940. doi: 10.1021/bi802027g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pédelacq J-D, Cabantous S, Tran T, Terwilliger TC, Waldo GS. Engineering and characterization of a superfolder green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotech. 2006;24:79–88. doi: 10.1038/nbt1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenman DJ, Huang Y-m, Xia K, Fraser K, Jones VE, Lamberson CM, Van Roey P, Colón W, Bystroff C. Green-lighting green fluorescent protein: faster and more efficient folding by eliminating a cis-trans peptide isomerization event. Protein Sci. 2014;23:400–410. doi: 10.1002/pro.2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoki S, Saeki K, Maki K, Kuwajima K. Acid denaturation and refolding of green fluorescent protein. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14238–14248. doi: 10.1021/bi048733+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J-r, Craggs TD, Christodoulou J, Jackson SE. Stable intermediate states and high energy barriers in the unfolding of GFP. J Mol Biol. 2007;370:356–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fersht AR, Matouschek A, Serrano L. The folding of an enzyme. I. Theory of protein engineering analysis of stability and pathway of protein folding. J Mol Biol. 1992;224:771–782. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90561-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews JM, Fersht AR. Exploring the energy surface of protein folding by structure-reactivity relationships and engineered proteins: Observation of Hammond behavior for the gross structure of the transition state and anti-Hammond behavior for structural elements for unfolding/folding of barnase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6805–6814. doi: 10.1021/bi00020a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DF, Waldner JC, Parikh S, Alcazar-Roman L, Pielak GJ. Changing the transition state for protein (un)folding. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7403–7411. doi: 10.1021/bi960409u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers JK, Pace CN, Scholtz JM. Denaturant m-values and heat-capacity changes—relation to changes in accessible surface-areas of protein unfolding. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2138–2148. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanford C. Protein denaturation. C. Theoretical models for the mechanism of denaturation. Adv Protein Chem. 1969;24:1–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews BT, Roy M, Jennings PA. Chromophore packing leads to hysteresis in GFP. J Mol Biol. 2009;392:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert MHJ, Georgescu J, Ksiazek D, Smialowski P, Rehm T, Steipe B, Holak TA. Backbone dynamics of green fluorescent protein and the effect of histidine 148 substitution. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2500–2512. doi: 10.1021/bi026481b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemmer WPC, Crameri A, Ha KD, Brennan TM, Heyneker HL. Single-step assembly of a gene and entire plasmid from large numbers of oligodeoxyribonucleotides. Gene. 1995;164:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00511-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover DM, Lubkowski J. DNAWorks: an automated method for designing oligonucleotides for PCR-based gene synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e43–e43. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarkina ON, Popova AG, Gvozdik EY, Chkalina AV, Zvyagin IV, Rylova YV, Rudenko NV, Lusta KA, Kelmanson IV, Gorokhovatsky AY, Vinokurov LM. Universal and rapid method for purification of GFP-like proteins by the ethanol extraction. Protein Expression Purif. 2009;65:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigner E. The transition state method. Trans Faraday Soc. 1938;34:29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chan HS, Dill KA. Chevron plots and non-arrhenius kinetics in simple models of protein folding. Biophys J. 1998;74:A128–A128. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19980101)30:1<2::aid-prot2>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information